Introduction: Documenting Blackness at the NMAAHC

Jason Fox & Mia Mask

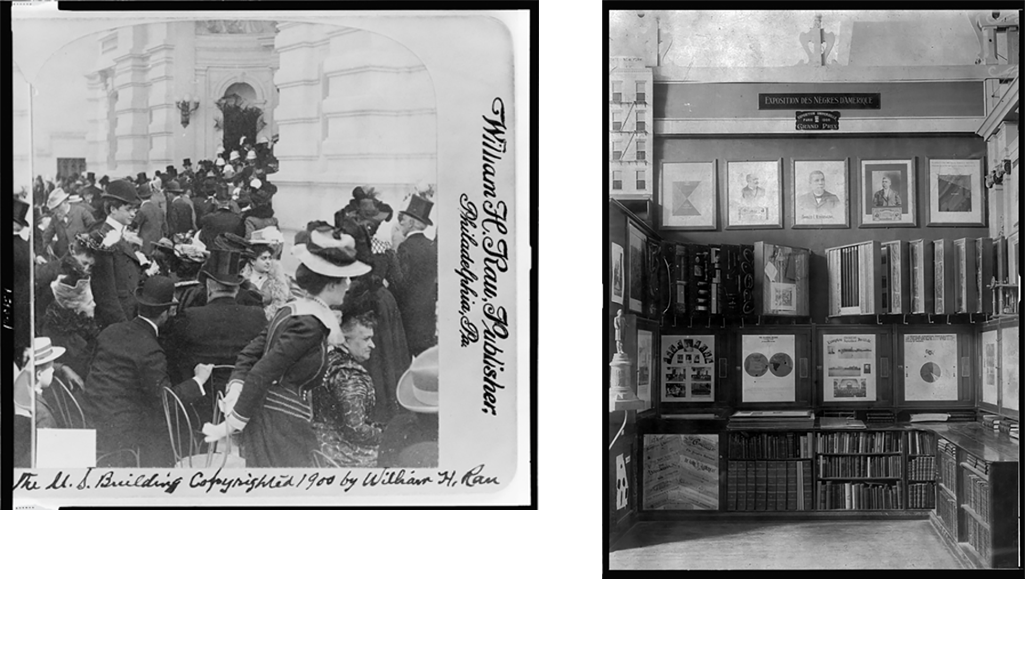

The National Museum of African American History and Culture opened its doors on September 24th, 2016. The museum’s establishment, construction, and grand opening occurred 121 years after Booker T. Washington spoke in front of the “Negro Building” at the Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition, and 116 years after W.E.B. Du Bois addressed audiences at the “American Negro Exhibit,” which he organized along with Washington for the 1900 Paris Exposition. Devoted to the collection, study, and display of objects relating to African American art, culture, and history, the museum is the nineteenth and one of the largest Smithsonian museums on the National Mall. A bold, bronze edifice, it sits in the center of a city sprinkled with lily-white federal monuments erected to memorialize a government which sought to prevent the realization of such an institution for nearly a century. The legacies of Dr. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington loom large over all manner of American museological undertakings, even if their political philosophies are more often divergent than complimentary. So which of their legacies shapes the new Smithsonian?

Washington’s photographic selections for the Paris Exposition emphasized African American students, industrious laborers, and leaders from Black communities across various Southern United States. These were photographs of reverends and teachers, doctors and nurses. They were constituent figures in what photography scholar Deborah Willis has described as “a new Negro visual aesthetic” at the turn of the 20th century.{1} White America enjoyed seeing itself through the lens of a Protestant work ethic and disciplinary spirit of white capitalism. Booker T. Washington accepted that lens as a structuring reality. He believed African Americans could realize their ambitions of equal opportunity by participating in the American capitalist system. The dozens of photographs Washington selected for the exhibition were intended to reflect that reality to Europe through images of a rising African American middle class. If the newly built Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture inherits the spirit of Booker T. Washington, then its documentary impulse might be said to represent an ideal whose value lay in historical documentation’s ability to stand in for and augment historical reality without upsetting it.

A museum shaped by the spirit of Du Bois, however, would approach nonfiction visual media quite differently. Du Bois, a master of granular histories, conceived of the Paris Exhibition initiative as an opportunity to transform African American representation. His rigorous preparatory research across the American South resulted in the display of sixty statistical charts, nearly 400 photographs, and a library that featured books by 200 African American authors.{2} If for Washington photography was a mode of representation, then for Du Bois it was an instrument of intervention, offering a means to challenge the Jim Crow era visual construction of African Americans as criminals. For example, Du Bois prominently displayed a series of photographs of African Americans that replicated the formal appearance of mug shots while summoning the iconography of the family portrait. Playing on the photographic tension between images of domestic tableaus and government documents, and between the codes of realism and formalism, his critical juxtapositions challenged the way white Americans constructed history out of a concept of whiteness in order to visualize power to itself. The photographs Du Bois displayed were documents of reality only to the extent that the reflexive viewing practices that his installation requested of viewers allowed for them to better see how images were used to naturalize existing orders of people and things.

figure 2. Selections by W. E. B. Du Bois for the American Negro Exhibit. Shawn Michelle Smith writes that the exhibition was “inaugurated by images that repeat so closely the formal style of criminal mugshots, Du Bois’s albums gradually come to resemble middle-class family albums.”

figure 2. Selections by W. E. B. Du Bois for the American Negro Exhibit. Shawn Michelle Smith writes that the exhibition was “inaugurated by images that repeat so closely the formal style of criminal mugshots, Du Bois’s albums gradually come to resemble middle-class family albums.”

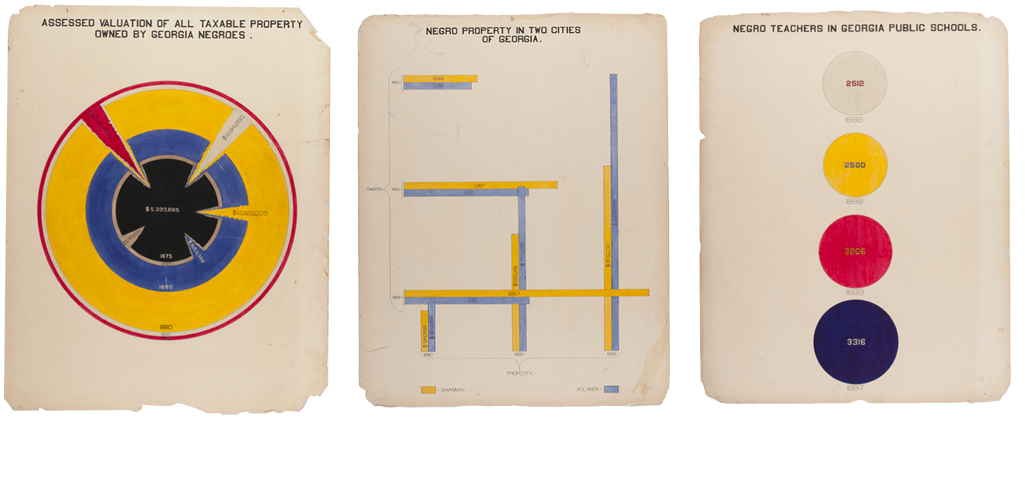

Alongside the photographs, Du Bois staged a stunning visual array of statistical graphs that charted literacy and employment rates, and marital and landholding statistics among Southern African Americans. They were arranged in an aesthetic style that preceded the emergence of the De Stijl art movement by two decades. We aren’t the first to be struck by his provocative combination of meticulously gathered sociological data, rendered in dynamic color fields consistent with the aesthetic concerns of high modernist painting. This journal issue represents one more response to his inspiring and brilliant visual provocations.

Du Bois, who coined the phrase “double consciousness,” understood well what it meant to see oneself through another’s eyes.{3} He also understood the ways that data not only reports about people in the world but also has a way of managing them. Expressed in these vibrant charts is an insistence against irreducibility to an instrumental way of seeing. For Du Bois, the emergent disciplines of sociology and documentary photography were about registering the deviations that unsettle static representations of “the evident rhythms of mankind.”{4}

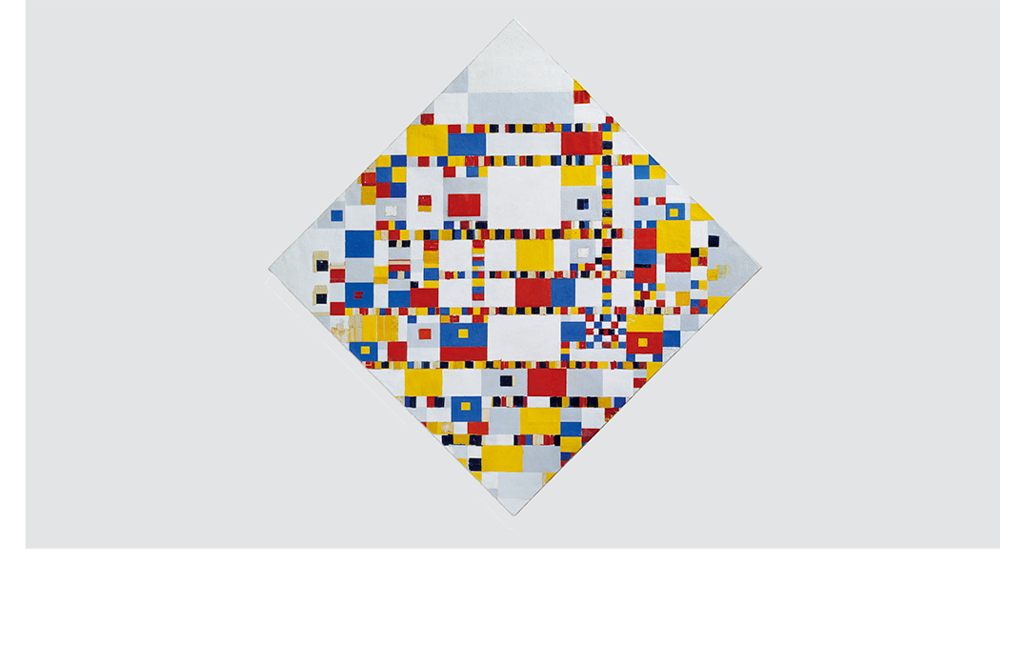

That Du Bois’s graphs are evocative of the painter Piet Mondrian’s best work is not lost on the poet and theorist Fred Moten, another agile thinker whose influence appears in the background across this volume. In an essay on Piet Mondrian and the jazz musician Cecil Taylor that Moten prefaces with a reflection on Du Bois, Moten riffs on Mondrian’s use of black pigment in his iconic, never completed painting Victory Boogie Woogie (1944). He describes it as “the victory of the unfinished, the lonesome fugitive, the victory of finding things out, of questioning; the victorious rhythm of the broken system.”{5}

In the same essay, Moten provocatively defines Blackness as an objective quality of paint, but that provocation is not without cause. With his assertion, he succinctly engages several dynamic forces in the Western construction of racial hierarchy. First, he links the transformation of people into objects with the artistic insistence popular among much of the mid-century modernist avant-garde that painting had escaped representation (and thus, social responsibility). Second, through a reading of Victory Boogie Woogie in which Moten sees black paint spilling across the boundaries of the painting’s grid system, he connects the black paint with Black-identifying people who refuse to participate in maintaining the normative order of things. In doing so, Moten extends into the 21st century Du Bois’s conviction that new representational strategies, unruly and analytic, are necessary to picture Black life on new terms in order to offer new terms for Black life.

The inspiration for this volume began the moment we, separately, visited the National Museum for the first time. Astonished by its ambition and scale, we found much to reflect upon in its curatorial juxtapositions, and we were struck by the feeling that the hum of the museum might resonate with the legacy of Du Bois more than it does Washington. As teachers of documentary and writers who reflect on it, we sensed that the museum invites a timely way of thinking about nonfiction media, and provides a space filled with case studies and questions through which to do it. In this issue, we have run with only a few of its provocations to energize conversations we wish to have about documentary practice and scholarship.

The first question: At a moment when Facebook and its younger social media siblings constitute the largest visual culture museum in the world, and when their expansive global networks dwarf more local identifications forged in and through the nation, why think about something so seemingly parochial as a national museum in the first place? One response is that announcing the failure of representation, politically or aesthetically, does not a post-representational world make. It has been fashionable of late, in some corners of Media Studies, to invoke social media platforms, both as material networks and as allegories for the way that contemporary power manages flows of people, information, and goods, in order to declare the end of representation. As the articles in this issue demonstrate, there are many compelling reasons to move beyond the paradigms of nation and representation. And, there are even more stubborn reasons why we cannot. Still, representation is best understood here as challenging the burdened concepts of identity and respectability.

This issue challenges identity as a bounded concept because the articles, and the visual works that each of them engage, do not seek to represent essential racialized or gendered identifications. It challenges respectability because each of the authors and works under discussion begin from, or with, a refusal to participate in the construction of the myth of the universal spectator of photography, an imaginary position of power from which everyone and everything is made visible, knowable, and exploitable. Moreover, the promise that anyone can occupy a position of benign respectability no longer holds. Not because we are in a post representational moment, but because representation was never benign in the first place.

“We suffer from the condition of being addressable,” Judith Butler says in a talk attended by the narrator of Claudia Rankine’s long-form poem Citizen.{6} Yet, awareness of this condition does not liberate Rankine’s narrator to the afterlife of representation. Rather, it prompts them to conclude that racist forms of address are not about rendering the target of those addresses invisible. Quite the opposite. It is the speaker who gets to withdraw from view. A friend advises Rankine’s narrator to withdraw from and to stop absorbing the world around her, something the narrator finds rather impossible, because that would also mean withdrawing from social relations entirely. What kinds of social and physical spaces, then, must be built in order to mitigate such violence?

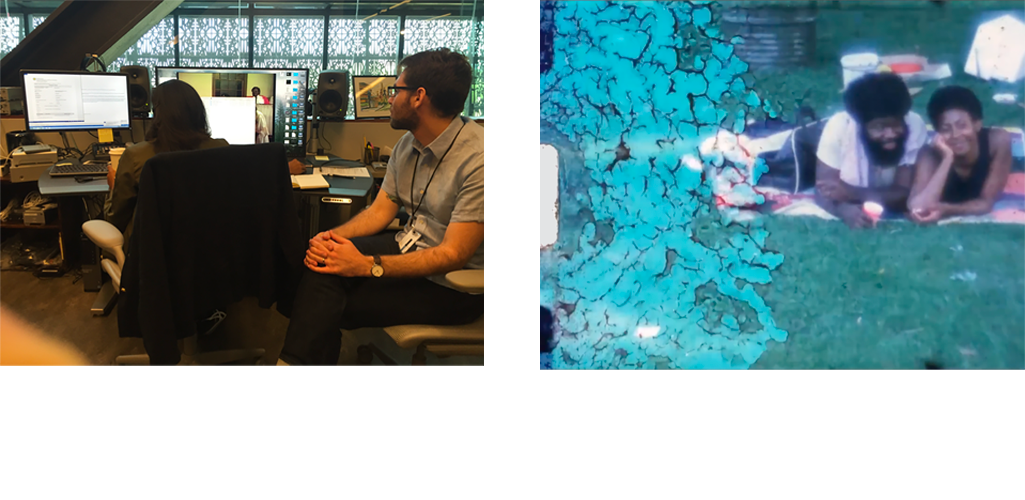

Reflecting upon the museum also returns us to some fundamental material questions. A museum is a poor place to assume a complete record, but it’s a good objective container in which to ask straightforward questions about what is included and why, how it is staged, and who is observing it. It also compels us to evaluate the social, institutional, and formal parameters into which the materials on display had to fit. Posing these questions succinctly, the artist and video maker John Akomfrah asks: “What constitutes a legend?” {Article 7}. That is, how do museums, and the publics they serve, decide what and who is worthy of remembering? How do histories become legends? How do they become central to cultural identity, and how are lived experiences pulled and stretched into the stuff of myth in the process? For Pearl Bowser, who donated a portion of her film archive to the Smithsonian, early American Black nonfiction film and photography must be reconstituted from discarded and scavenged fragments. They become legends in another sense, “standing as primary text(s) for lost segments of that history” like keys on a map.{7} The peripheral materials she preserved and researched continue to reveal the centrality of the works and people they reference, not just to Black historical experience but to American documentary at large.

In Bowser’s telling, her sharp archival eye for the resonant residues— newspaper clippings, editing exercises, sample reels, and diaries—of Black nonfiction media practices that she spent a lifetime recovering and preserving was placed in the service of activism rather than academics. In an interview with scholar Alexandra Juhasz, Bowser discusses the time she spent organizing an ongoing screening and discussion group for Black teens, explaining that she “realized that when you do something in a public space, in a community where you’re involved in attempting to share the history, you become something…you become a key or kernel from which people can be challenged, from which they can build other things, or from which they can see possibilities.”{8} Bowser may have been referring to the new forms of imagination her screening series provoked, but the reference is equally material. Her early donation of materials in 2012 constituted one of the museum’s first moving image media collections, and one of the most lasting effects of this “kernel” is not the way it allows for speculation about the past, but in the preservation priorities and protocols it established as a guide for the museum’s future.

Thinking about the intersectionality of documentary filmmaking and Blackness is essential. It is impossible to make sense of documentary film history and practice without Black diasporic representational counter-cinema. Blackness is a term with a meaning that often appears self-evident, but in practice seldom is. As a form of consciousness, Blackness refers to at least two concepts in this volume. First, it signifies an Africanized experience of race in and through the United States. Second, because Blackness exists in relationship to Whiteness, it signals the Euro-American ideological and material effects that continue to sustain white supremacy. It also marks the role of the camera in legitimating the modern construction of racial hierarchies as the only way the world could be visualized. Blackness comprises past experience, individual and collective forms of agency, and the structures that police them. In disciplining documentary, structure has historically taken precedent. Tracking all of the manifold and evolving ways the structuring forces of visual culture have sought to render Blackness alternately invisible and hypervisible is beyond the scope of this issue. Here, a few examples will suffice.

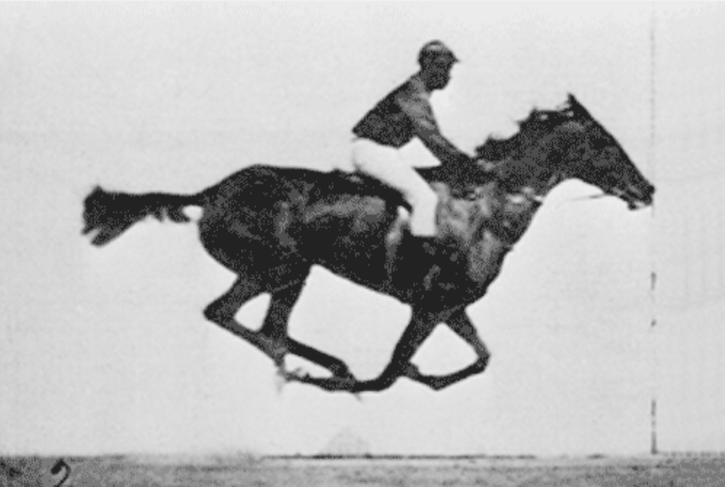

figure 6. Animated sequence of jockey riding a galloping race horse. Photos taken by Eadweard Muybridge and first published in 1887.

figure 6. Animated sequence of jockey riding a galloping race horse. Photos taken by Eadweard Muybridge and first published in 1887.

In his examination of the athletic impulse that animates Kevin Jerome Everson’s “presentational aesthetics,” cinema scholar Jeff Scheible points to a scene of loss featuring overlooked and unnamed stars who appear at the beginning of the documentary canon {Article 3}. The names of the African American jockeys in the images of Eadweard Muybridge’s famous motion studies were never recorded. Yet the names of the horses —Occident and Sallie Gardner—were. Scheible references this absence in order to call attention to the need for a different kind of analytical discussion. The presentational aesthetics of Everson’s cinematic engagements with African American athletes, Scheible argues, are primary sites to address the ways they frame the thinnest of boundaries between labor and play and bodies and technologies. Nonfiction visual history has routinely denied African Americans subject status by reducing Blackness to the overlooked status of infrastructure—more often as ground, less frequently as figure. The contributors to this volume redress the absence of Blackness from documentary history by drawing careful attention to the ways filmmakers, curators, and archivists have crafted films, engaged filmmakers, forged expressive and liberating opportunities from dominant discourses, and reimagined representational modes.

Archives are primary sites for addressing representational inequities because historical archives tend to preserve the colonial, imperial, and ethnocentric practices undergirding the capitalist marketplace from which they derive funding. Consequently, they often reflect the hegemonic or monolithic master narratives rather than the complex and contradictory narratives of anti-colonial contestation, imperial discord, and politicized rebellion that have transpired. Confronting the erasure of people and events that were deemed as surplus to historical meaning, several contributors are drawn into the orbit of the photography scholar Tina Campt and the cultural historian Saidiya Hartman. Campt and Hartman demonstrate novel methods to craft new modes of agency—a loaded term that Campt defines straightforwardly as the capacity to imagine something different than what is—from the “differential or degraded forms of personhood” of state, colonial, and historical archives.{9} Both Campt and Hartman view the “historical archive” as a verb rather than a noun. And for each, their settings are stages more than storage lockers to liberate African American figures from judgement, classification, and historical neglect.

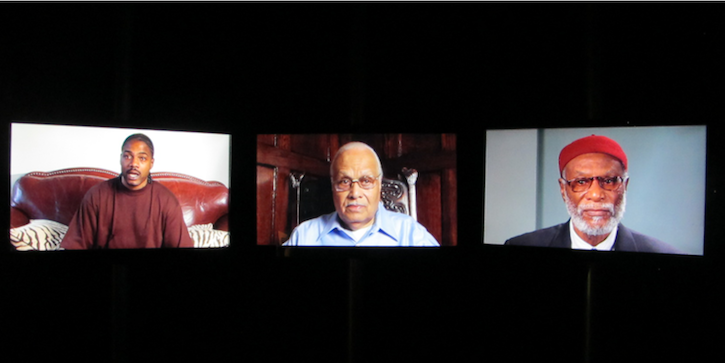

figure 7. In lieu of a pedagogical video introduction to the American Art section of the National Museum of

African American History and Culture, QUESTION BRIDGE (2012), created by Chris Johnson, Hank Willis Thomas,

Bayeté Ross Smith and Kamal Sinclair, greets visitors to the American Art exhibition. Most of the other

sections of the museum are framed by pedagogical videos that were produced by the Smithsonian Channel, a

subsidiary of the CBS Corporation and Showtime Networks.

figure 7. In lieu of a pedagogical video introduction to the American Art section of the National Museum of

African American History and Culture, QUESTION BRIDGE (2012), created by Chris Johnson, Hank Willis Thomas,

Bayeté Ross Smith and Kamal Sinclair, greets visitors to the American Art exhibition. Most of the other

sections of the museum are framed by pedagogical videos that were produced by the Smithsonian Channel, a

subsidiary of the CBS Corporation and Showtime Networks.

Interrogating police mug shots of 1960s Freedom Riders in the Mississippi Department of Archives, for example, Campt asks two deceptively simple questions of the images in front of her: What is the pictured subject’s point of view? And, what had transpired for her (as a viewer) to encounter this person’s particular image? Asking these questions is a way of animating the meanings and unruly power of the African American subjects pictured. Moreover, similar questions inform artist and archivist Ina Archer’s contribution to this issue {Article 2}. Campt’s method works through the indicative mood, rescuing latent meanings in the images she studies through close attention to subjects’ postures and poses, as well as to the social conditions that produced the photographic encounters.

Campt’s writing extends and revises the writings of Allan Sekula and John Tagg, both of whom viewed museums and archives as spaces where historical conditions become naturalized, and thus invisible. But where Sekula was interested in analyzing modes of erasure, Campt would direct us to reconstitute the subjectivity of the erased by considering their own perspectives and positions, literally and figuratively, in such images.{10} In considering their presence as a mode of performance, she suggests that one can acknowledge their presence and the sitters’ own methods for refusing the gaze of power. It’s not enough, she insists, to simply point to absence. For Campt, the real work involves restoring the presence of overlooked figures as a way to imagine the potential impacts, past and present, those figures might still have on our political imaginations.

Where Campt employs the indicative mood, focusing on what is overlooked in and around representational images, Hartman prefers the subjunctive, viewing archives as spaces from which to adopt speculative strategies in order to “tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling.”{11} For Hartman, representational strategies of writing and imaging have long been a form of enclosure, tied to the logic of the property form. Yet, she is committed to rehearsing the problems of representation rather than moving beyond them. That’s because for Hartman, her “own narrative doesn’t operate outside the economy of statements” and representations that she aims to unsettle. For her, possibilities for the future are inextricably tied to what continues to count as official history in the present.{12} Those who claim otherwise—that our contemporary visual moment can be characterized as post representational—confuse a regulatory fiction with a utopian aspiration. The claim lands with the same thud as that other claim that our contemporary moment can also be characterized as post-racial.

Most recently, this outlook has meant for Hartman assembling archival fragments in order to construct an anthology of Black women’s lives that coincided with the onset of the U.S. Progressive Era. In particular, she focuses on women who clashed with and bore the brunt of the Progressive Era’s embrace of reason as the intellectual scaffolding for social engineering. The years 1890 and 1935 are the bookends that frame Hartman’s Wayward Lives (2019), a timeframe “decisive in determining the course of black futures.”{13} Coincidentally, the same timeframe was decisive in determining the course of documentary, shaped in no small measure by the progressives and pragmatists who are the antagonists of Hartman’s book.

Captions and wall text, filing systems and database naming conventions are the logistical interstices bridging viewers and the unruly meanings of the images and objects they describe. But the accompanying sign is frequently mistaken for the object itself, determining in advance the possibilities for engagement with images. This is likely why Hartman’s Wayward Lives frequently omits accompanying credits and captions for the images that fill its pages, and also why the book makes frequent mention of the police officer and the sociologist in the same breath. Each occupation provides a direct means for controlling defiant subjects.

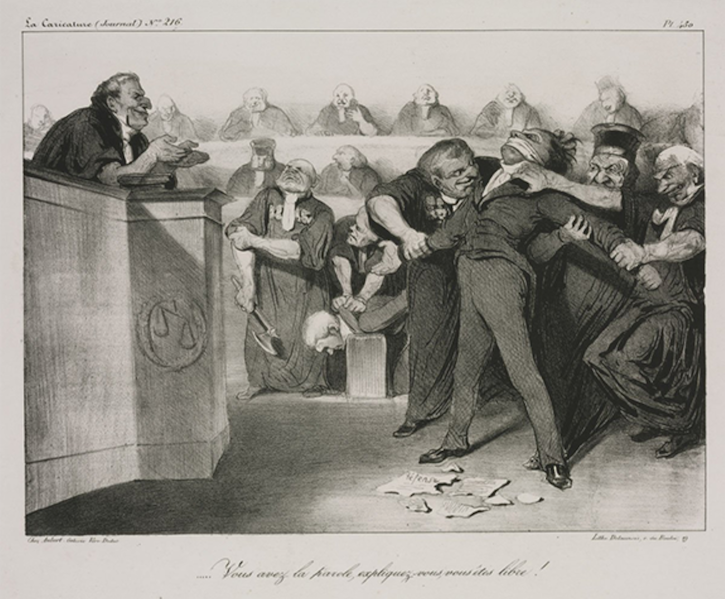

figure 9. Honoré Daumier, “Vous avez la parole, expliquez-vous, vous êtes libre!” LA CARICATURE, no. 216, May 14, 1835.

figure 9. Honoré Daumier, “Vous avez la parole, expliquez-vous, vous êtes libre!” LA CARICATURE, no. 216, May 14, 1835.

Hartman’s concern finds further support in the recent writing of Michael Gillespie, whose Film Blackness (2016) provides a conceptual reference point for Ina Archer as well as Liz Reich’s engagement with the visionary work of filmmaker Terence Nance {Article 5}.{14} Gillespie’s starting point is well summed up by Honoré Daumier’s infamous judge who exclaims, “You have the floor, explain yourself, you are free” to a gagged and restrained plaintiff that has been brought before him. Gillespie wonders why the violence of collapsing representation and referent, which was so clear to Daumier nearly two centuries ago, doesn’t extend to the frequent conflation of “race in the arts” with “social categories of race” in contemporary discussions of Black cinema. When this conflation happens, argues Gillespie, “black films” and their viewers are placed back in the role of Hartman’s progressive sociologist, diagnosing social problems and prescribing solutions. What if, instead, Black film and Blackness more broadly, indicated an investment in creative expression, critical capacity, and relational experience freed from exclusively embodied approaches to race?

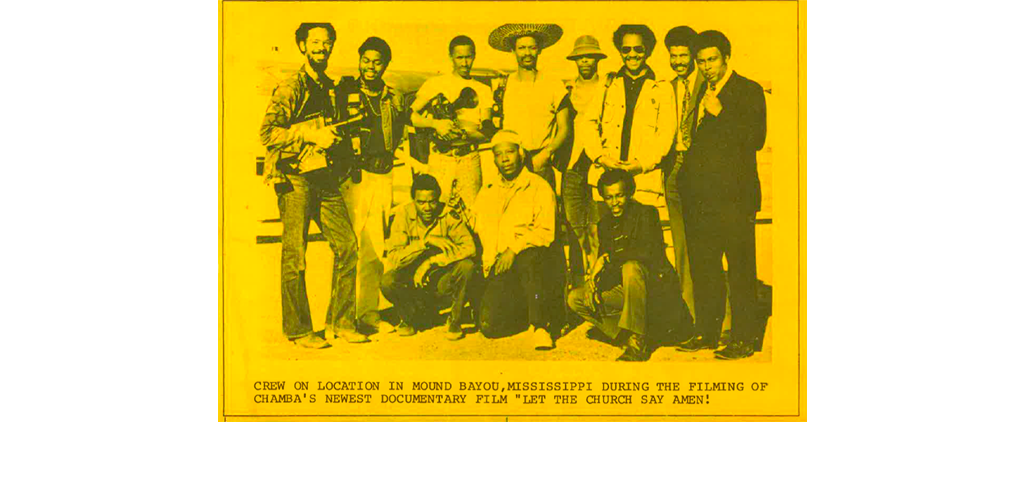

The challenges that these provocations pose also point to one of the reasons we include a conversation with the filmmaker Stanley Nelson {Article 4}. A master of media archives, his Firelight Media produced many of the exhibition videos installed throughout the National Museum of African American History and Culture. As Nelson tells it, producing these installations meant being clear in his intended audience, and moving from there. For Nelson, this entails focusing first and foremost on addressing African American audiences, and then navigating the economic, legal, and content-tagging conventions of contemporary corporate media archives in order to transform their historical contents from static meanings to dynamic characters in their own right. For contributor Jon Goff {Article 6}, on the other hand, the social value of 20th century African American Christian theological movements have been defined not by African American consciousness but rather through those movements’ proximity to white-dominated religious institutions. This may also explain the lack of attention given to St. Clair Bourne’s Let the Church Say Amen! (1973), a portrait of a young man who looks to Black liberation theology in his pursuit of a meaningful discourse of truth and social justice that might use Blackness as a force for structural change rather than assimilation.

The essays gathered here expand upon how we frame Blackness as an operative term. And, the contributors play a more fundamental role in constituting new spaces for documentary. Documentary is what we make with it, it is who gathers under its sign, and it is the terms of agreement that are reached once people are gathered there. Wherever we gather, we create spaces of inclusion and exclusion, though seldom under conditions of our own making. Agency, the ability to imagine something differently, is thus chiseled out of the bedrock of material and ideological structures.

The fight for futurity, another term that animates these essays, plays out within already existing institutions and the representations that uphold them. The voices gathered in this introduction—W. E. B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, Tina Campt, Saidaya Hartman, Claudia Rankine, Fred Moten, Michael Gillespie—and the contributors to this volume who follow, all make for more dynamic discussions of documentary in the classroom, at the museum, and in festivals and working groups of all kinds. They also pave the way for a more radical approach to the uses of documentary beyond these spaces. What unites all of these voices is their fundamental challenge to the superintending status of the historical document as something that hovers over existing worlds, explaining those worlds in advance of the people who occupy them.

Du Bois, whose Black Reconstruction in America (1935) showed more interest in the undocumented, collective actions of striking abolitionist workers in the Southern US than the legislators whose bills and speeches are much better documented, demonstrated long ago how a more agile approach to the archive makes possible new forms of agency. We inherit the spirit of Du Bois, for whom history and sociology were pathways to imagining what self-determined and democratic futures might lie just ahead. The radical approaches to time that are explored in this issue reveal conceptual frameworks and artistic methods for organizing against racial structures of domination. And sites of historical memory offer Black visions for remaking the future outside of Western racialized infrastructures and outside of didactic and sober modes of address.

With an emphasis on make, Fred Moten asks: “What are we to make of the fact of a sociality that emerges when lived experience is distinguished from fact?”{15} That future isn’t made yet, but potential futures find flashes in the past and present.

Title Video: Selections from more than sixty statistical charts, produced by W.E.B. DuBois for the 1900 Paris Exposition.

{1} Deborah Willis, “The Sociologist’s Eye: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Paris Exposition,” in A Small Nation of People, edited by David Levering Lewis (New York: Amistad, 2003), 53.

{2} Elisabetta Bini, “Drawing a Global Color Line: ‘The American Negro Exhibit’ at the 1900 Paris Exposition” in ed. Guido Abbattista, Moving Bodies, Displaying Nations: National Cultures, Race and Gender in World Expositions Nineteenth to Twenty-first Century (Trieste: EUT: Edizioni Università di Trieste, 2014).

{3} W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

{4} W. E. B. Du Bois, “Sociology Hesitant,” boundary 2 27, no. 3 (2000): 37–44.

{5} Fred Moten, “The Case of Blackness,” Criticism 50, no. 2 (2008): 177–218.

{6} Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric (London: Penguin Books, 2015).

{7} Pearl Bowser, “Pioneers of Black Documentary Film,” in Struggles for Representation: African American Documentary Film and Video (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999).

{8} Alexandra Juhasz, Women of Vision: Histories in Feminist Film and Video (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2001).

{9} Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 3.

{10} Regarding Sekula, take for example Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre’s photograph of the Boulevard du Temple, dated to around 1838, which is frequently upheld as the first photograph to capture a human figure. Sekula, ever attuned to the ways in which productive labor is so often literally or figuratively left out of the photograph, noted that Daguerre’s image figures not one but two bodies if one includes the shadow of a bootblack shining the shoes of the stationary man. Sekula’s criticism isn’t directed towards the image, but to the caption Life magazine affixed to the image, which directs viewers’ attention to the patron and away from the laborer at his feet. The caption appears neutral, and thus neutralizes its own power to condition viewers’ interpretation.

{11} Saidiya V. Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (June 2008): 11.

{12} Ibid.,14.

{13} Saidiya V. Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (London: Serpents Tail, 2019).

{14} Michael Boyce Gillespie, Film Blackness: American Cinema and the Idea of Black Film (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

{15} Fred Moten, “The Case of Blackness,” 188.