Conspiracies and Caretakers: Making Homes for African American Home Movies

Ina Archer

A Peoples Playhouse (circa 1947) presented by the American Negro Theatre, is a World War II-era documentary featuring a very young Ruby Dee alongside theatrical stalwarts of the era like Fredrick O’Neil and the playwright Abram Hill. Linking its fundraising plea to the war effort, the film reuses newsreel footage from a concurrent propaganda film The Negro Soldier (1944). According to John Klacsmann, an archivist at Anthology Film Archives, his late boss Jonas Mekas looked at the unidentified film—a bit of an outlier in a collection that focused on the preservation and exhibition of experimental and independent film—and said “that looks old.” With that declaration, he unwittingly initiated a collaboration between Anthology and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture to preserve the short work. The film’s narrator connects viewers to the everyday citizens on screen— factory-workers, clerks, war-workers, and teachers—that they may have encountered on the streets of New York City. For me, it’s delightful to see that the people we recognize on screen are Black. Even more extraordinary, these ordinary African Americans on the streets of Harlem are professional actors!

A PEOPLES PLAYHOUSE (American Negro Theatre, ca 1947).”

A Peoples Playhouse is emblematic of The Great Migration Home Movie Project because it too situates the work of African American image making in the hands of African Americans. And it demonstrates that many of the cinematic archives and histories we thought we knew are not as white as we tend to think them to be. The initiative reveals the importance of preserving and supporting African American creative self representation, specifically from everyday family and community life, and it contains the capacity to counteract negative depictions of Blackness. “It’s your story too and this is how you are part of it.” I use this orphaned film to consider the continuities between my art practice, the Center for African American Media Arts (CAAMA) film and media collection, and the Great Migration Home Movie Project at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, where I am a media archivist. This is how I am a part of it.

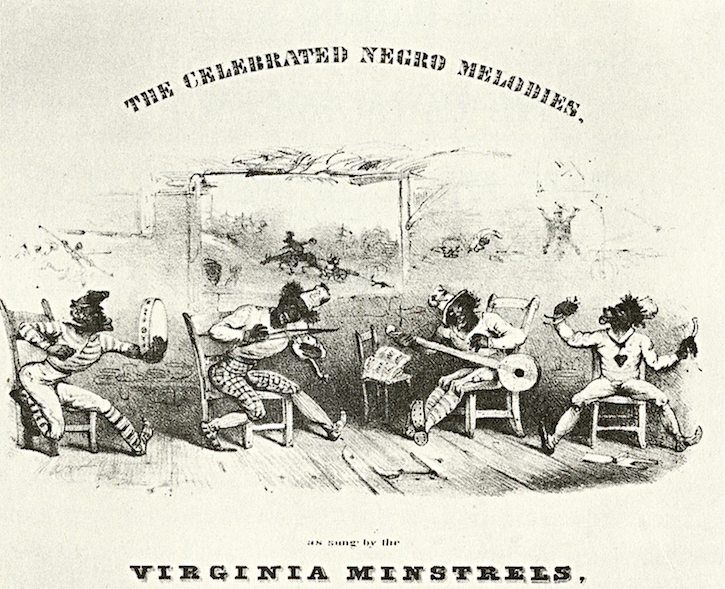

As an artist and an archivist, my work intervenes on representations of African Americans through re-making, re-editing, and re-contextualizing images of Blackness in early commercial cinema. When I began making work in the 1990s, academic film studies, Hollywood, and the burgeoning archival film communities—all communities that I wished to enter—were consumed by centennial celebrations of the cinema. Lists of the “100 Greatest Films” were named by the American and British Film Institutes. Their interest in registering hierarchies and granting canonical status imposed a restricting chronicle of cinema, and one that I needed to push back against. Since that moment, my practical knowledge of film history, production, and preservation has developed on a continuum. Using commercial, archival, and original footage as material, and by employing appropriation and montage as strategies, I negotiate the relationship between the frequently marginalized and their media representations. Thematically, I map contemporary practices of representation onto past footage using digital tools. As an example, I have investigated the “persistence of minstrelsy,” and racial and ethnic masquerade at the inception of nascent technological moments in entertainment. The legacy of blackface continues to inhibit African American participation in film and has remained ever relevant, as evidenced by the tiresome revelations of collegiate blackface drag by Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, and his Attorney General Mark Herring (“Virginian Gentlemen, Be Seated!”).

figure 1. Detail from cover of THE CELEBRATED NEGRO MELODIES, AS SUNG BY THE VIRGINIA MINSTRELS, 1843.

figure 1. Detail from cover of THE CELEBRATED NEGRO MELODIES, AS SUNG BY THE VIRGINIA MINSTRELS, 1843.

Mining a bottomless pit of film images, ranging from the bizarre to the utterly repellant, soon became exhausting. I love to attend repertory screenings and revel in Film Forum’s exhaustive surveys of studio produced early sound films, but throw a rock at a pre-code musical festival and you’ll hit a minstrel upside the head every time. Every screening is likely to have at least one discomfiting moment of racial affront. As a cinephile, I experienced a kind of Stockholm syndrome; that uncomfortable moment repeated every time a character somehow ended up in burnt cork, mud, or makeup.{1} I’d feel like a spotlight was being shone down on me in the middle of the theater, exposing my Black presence in order to ruin everybody else’s fun. And yet I would keep attending. Something in the screenings that I attended felt visceral and pleasurable, but also strange and just plain wrong—undoubtedly central to the development of the musical comedy genre. I am intent on working with this material as a conservator and a programmer but as I get older my tolerance dwindles.

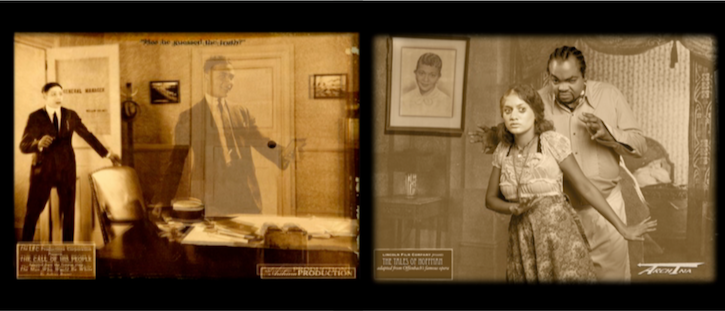

In response, if only semi-consciously, was the creation of my ongoing video and installation project The Lincoln Film Conspiracy (LFC). This work was inspired in part by my encounter with Pearl Bowser’s film Midnight Ramble: Oscar Micheaux and the Story of Race Movies (1994), which was broadcast on public television in the mid-nineties and which I first watched on a VHS rental copy when I was an employee at Evergreen Video store, located across the street from Film Forum, New York’s incomparable, non-profit arthouse theater. These two institutions, Film Forum and Evergreen, were formative for me. The theater combined repertory with first-run independent films, and Evergreen’s extensive VHS library specialized in rentals to academic film programs, which offered me free access to otherwise difficult to access early cinema.

Bowser’s documentary introduces fragments of a lost film, By Right of Birth (1921), made by The Lincoln Motion Picture Company, which produced five films in the early 1920s. The fragments are the only extant footage from the company. Bowser uses these fragments to introduce a record of Black filmmaking prior to that of Oscar Micheaux, whose distinctive work I was already well familiar with. In the silent sequence, actors Anita Thompson and Clarence Brooks “meet cute” when damsel in-distress Thompson’s horse bolts and heroic Brooks rescues her. Riding dressed in natty equestrian garb, Thompson accidentally falls from her white steed. Calling out for help, she catches the attention of Brooks who is fishing nearby, equally dapper in a sweater, tie, and straw boater hat. Running to her side, he tries to capture her errant horse in a scene depicted through amusing cutaway shots framed by a circle vignette. After wrangling the horse and helping her back into the saddle, Brooks tips his boater hat to her, his gesture pictured in a charming close-up seen from her high- angle point of view. The remaining unedited collection of shots that surround the edited sequence are stored and catalogued at the Library of Congress, now readily accessible for viewing online.

BY RIGHT OF BIRTH (The Lincoln Motion Picture Company, 1921).

Captivated by the clip, I developed a story that imagines the travails of a researcher who is investigating the disappearance of the studio backlot and film catalog of an early, technically-advanced African American movie corporation named The Lincoln Film Company, as well as a subsidiary sound unit named Archina Studios. It is likely, I suggest, that the corporation was disappeared by extraterrestrials.

Excerpts, THE LINCOLN FILM CONSPIRACY PROLOGUE (Ina Diane Archer, 2008). Courtesy of the artist.

With the support of a Creative Capital grant and encouragement from Terri Francis, I further developed the project. The first iteration of the film, originally titled The Lincoln Film Conspiracy Prologue (2007), screened as a short and exists as a trailer of a trailer within which is another trailer from a lost Lincoln/Archina production, Black Ants in Your Pants of 1926. In a way, The Lincoln Film Conspiracy has developed into a kind of movie “corporation” or studio, generating the foundation of my own artistic practice. It has become a self-generating archive.

The project is both a fantastic imagining of an alien preservation archive and a framework for the actually existing personal archive of my work. I draw from a collection of other pre-existing images to create the semi- fictional Lincoln materials. For example, my unfinished project from 1991, La Tête Sans Corps / The Head Without a Body, about the discovery, reanimation, and exploitation of a young Black woman’s disembodied head, is a sci-fi story that has been revived as a Lincoln Film Conspiracy horror/romance. Using material from this work, I crafted a series of lobby cards (small in-theater advertisements) with stills from key film scenes that are intended to be displayed in the foyer of cinemas. These sets of cards, modeled on those of the Reol Film company, are invaluable for speculating on the content of non-extant films.{2} Family and friends are disguised throughout as characters in these films and as players from the company, thus archiving my emotional life as well. Consequently, its production has ebbed, flowed, hesitated, and restarted.

Essential to the themes of my LFC project is the creation of popular films and quotidian images, separate from but related to the genre of uplift cinema, as articulated by Allyson Nadia Field. Field writes about producer George W. Broome’s imaging of Tuskegee Institute in the 1910s:

Broome’s films’ model of uplift cinema consisted of a combination of actualities with the local film, a type of filmmaking whereby spectators were drawn to a motion picture exhibition by the possibility of seeing themselves and their communities projected on screen… Although no public accounts survive of Broome’s audiences or of the reception of his films, his filmmaking practice represents a significant attempt to reclaim the medium from its employment in the ridicule of the race.

In Broome’s exhibition, local African American spectators were shown an image of themselves as respectable and communal—a fully constituted social body. The footage is not extant and therefore we can only speculate on its representational capabilities but the very fact of the actuality footage —and its enthusiastic reception by the public—is an assertion of resistance to the dominant misrepresentations of Black people in cinema of the era.{3}

The lost Broome films are precedents to narrative films like By Right of Birth (1921), produced by brothers George P. and Noble Johnson, and the Lincoln Motion Picture Company.

In Midnight Ramble, Bowser narrates over a clip of the By Right of Birth fragment, maintaining that the characters in the early films cast and produced by African Americans were “educated, well-to-do. They had a social lifestyle that was uplifting. They didn’t gamble, they didn’t drink… in other words they were almost like morality plays…” For Bowser, Lincoln Motion Pictures’ productions exemplified the trend toward morally enlightening themes in Black film narratives. These themes were often made explicit in the films’ titles, such as The Realization of a Negro’s Ambition (1916) or The Burden of Race (1921), the latter of which was produced by Reol, a contemporary white-owned company that featured the Black acting troupe from Harlem’s Lafayette Theatre. But Reol’s lobby cards (none of which have survived) also suggest less elevating fare. Titles such as Jazz Hound (circa 1920s) and Easy Money (circa 1920s) speak to an appetite for more salacious stories. The push and pull between uplift and indulgence in these early comedies and melodramas provided tension for my own Lincoln Film Conspiracy.

Retaining the name “Lincoln,” I also fabricated props and posters to blur the boundaries between my own project and the historical objects I was engaging with. Yet, I never attempted to create seamless technical effects that might render the boundaries invisible. I preferred to allow viewers to see around the edges, literally and figuratively. To give my work a handmade feeling, collaged and layered images allow viewers to see how the videos were constructed, and blue screens often remain visible around the edges of the frame. This method of working also proves a way of creating a visual archive of the technologies I have had access to at any particular moment.

But not everyone shared my passion for fooling the eye with speculative archives. In 2010, I was invited to show what existed of the project in a group exhibition in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood. The gallerist, like others to whom I pitched the project, was enthusiastic about the premise of the rediscovery of early Black cinema and the recreated lobby cards of disappeared movies, but nonplussed by the revelation of alien abduction. I was advised by one of the gallerist’s deputies to refrain from that story turn, for I would be considered a little crazy at best, and disrespectful of African American history at worst. This seemed like odd cautioning in an art world context. Nonetheless, viewers still occasionally express the desire for the LFC to be an actual documentary. Suddenly caught in the crosshairs of desire for historical certainty, I summoned courage from a mentor of mine, Cheryl Dunye, whose first feature film, The Watermelon Woman (1996), engaged hidden archives of Black and lesbian images. As a faux documentary—an intriguing, emotionally resonant genre—it addresses artifacts that no longer, or never even existed. Conspiracy theories emerge from our need to understand untenable events and conditions. LFC is a conspiracy story that addresses my concerns about the invisibility of Black cinema and the conceivable reality that there has been an actual disappearance of African American quotidian filmed images. So, it felt a bit like predestination when I landed at the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture just as they were launching the Great Migration Home Movie Initiative.

figure 2. Lobby Cards, stills from the LINCOLN FILM CONSPIRACY. Courtesy of Ina Archer.

figure 2. Lobby Cards, stills from the LINCOLN FILM CONSPIRACY. Courtesy of Ina Archer.

The Great Migration is a playful and hopeful contemporary play on the phrase so central to 20th Century African American history. The project offers an African American public the opportunity to “migrate” their analog media into a digital format. Films and videotapes long unseen could once again be accessed. Furthermore, the phrase Great Migration speaks to the need for the project to exist both as a way to retrieve images from obsolete formats and as a method to trace—through amateur home movie images—the resettlement routes of African Americans, documented due to the availability of affordable small-gage film formats and, later, home video cameras. The Great Migration grew out of Jasmyn Castro’s emergent archive, the African American Home Movie Archive (AAHMA) which was conceived as a registry that would allow researchers greater access to African American home movies.{4} The project quickly grew into a collection that would “promote a broader perspective of African American history and culture by encouraging access, research, and reuse of these films.”{5}

Castro cites commercial cinema’s historically troubled (to put it mildly) representations of African Americans, and its lack of diversity in front of and behind the camera. Where commercial media failed to responsibly picture African Americans or to empathically relate to African American history, African Americans embraced amateur motion picture technologies to record home movies. Castro regards home movie documents as correctives to failed commercial representation. She suggests that these records were made for entertainment within a family context and rarely intended for public exposure outside of the community. I argue, however, that the canny and intentional construction of so many of the films that we digitize reveals that many of their makers often also hoped for more than just private engagement. It is now up to the visitors of the Great Migration Lab to intuit these films’ significance, to discover the performances they contain, and to contextualize and create their historical significance.

According to the museum’s media agreement, films digitized in our lab belong to the individuals who brought them in (digital files are titled with their family name). There is then the option to allow the films to be added to the museum’s study collection. Recently, some archival researchers applied to CAAMA for travel images for use in an upcoming non-fiction film about The Negro Motorist Green Book. For the Green Book documentary, we advised the families to discuss the project with the filmmakers and to negotiate access to the clips including the possibility to charge a fee for usage. If an agreement is reached between the parties, we provide high resolution clips to the producers. I mention the Green Book project because we encourage family members to have a say in how their images are being used to illustrate historical narratives in nonfiction projects (the majority of requests are for documentaries) even if the financial transaction is merely symbolic, stressing that the families aren’t required to divest their media images as anonymous documentary footage.

I remain curious to see how various filmmakers will use the footage that they have requested to represent “black life worlds” or to stage new ones, even if they are situated in the past, like my own speculative works.{6} Could the study of the Great Migration media circumvent racial fantasias perpetuated by films like the recent, Oscar-winning narrative film, The Green Book (2018). Can this archive interrupt the pattern of filmmakers reducing African Americans to individuals in need of protection by white saviors, such as the reduction of musician Don Shirley as a unicorn isolated from his Black (middle class) family and community in The Green Book? It remains to be seen.

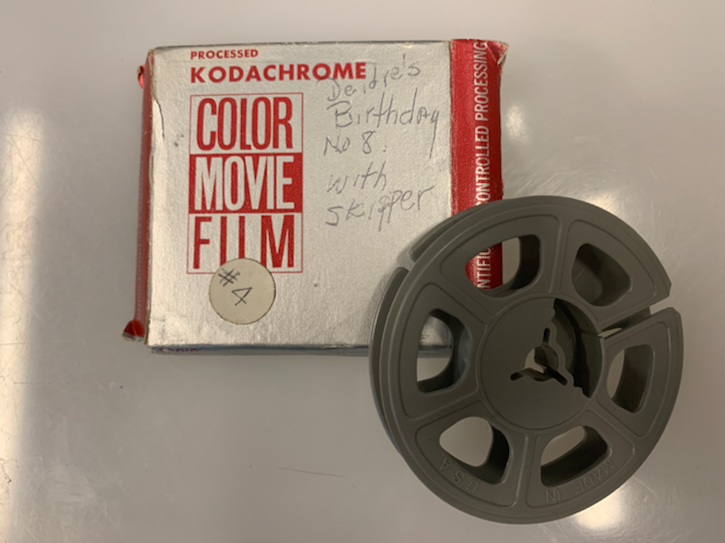

In the early days of the initiative we needed ringers to fill sessions, so we invited friends and employees at NMAAHC and other Smithsonian units to bring in their family films and tapes. Our media team also brought in their own home movies and videos to scan. Accordingly, one day I brought in a reel of Super 8mm film from home that I had never viewed. Practicing the same methods that we use for all of our public appointments, I inspected the film (which could have used some cleaning), added head and tail leader, threaded it on the scanner, and ran the 200 foot reel. Later, when I was alone, I had the chance to watch the digitized footage for the first time. My interior narration was not so different from many other participants that had visited the museum’s lab or who came to our community digitization events in Baltimore and Denver:

‘Deirdre’s Birthday No. 8 with Skipper.’ Transferred and preserved by the Great Migration Home Movie Project.

It’s the living room of our house in Panama! On the Canal Zone at Albrook, AFB. It’s my birthday and we must have had an overnight or maybe will be having a sleep-over at the house (the one with the red tile roof) because I’m wearing my favorite quilted pink bathrobe (my mother sewed it) but why is my friend Margo, who wore oval glasses—one of the few kids I knew who wore glasses for real—wearing a party dress with fabric very similar to my flowery, sleeveless, dressy-dress that had pleats that fell from the shoulder and a white pique sailor collar? And why is Maggie there, the little sister of my best friend Barbara without Barbara being there?

(The group is having a cake, as per usual with African American home movies, where birthday parties, Christmas get-togethers, and Thanksgiving dinners predominate)

We’re around the oval dining room table that my dad’s sister Aunt Hilda (who owned a ghetto fabulous bar in the ’70s at 136th and Lenox Ave called The Satin Doll) gave him to store when we moved to the house in New Rochelle. It was a big, ornate, gilt-edged thing (hence the tablecloth) and not mom’s (nor dad’s) taste at all. Mom preferred the Danish modernist furniture that they bought when we were living in Paris (where I was born) and shipped the furniture to the different air bases where we lived over the years. I remember the chandelier that hung over the table—it was there when we bought the house because we were a bit like snails, just moving into a preexisting home shell—which I was fascinated by. I would remove one or two of the crystals on the sneak to hide in my jewelry box and to create giant diamond accessories.

And mom is there, shy in front of any type of camera but chic as always, her hair up with the curled hairpiece that she would wear on special outings. Usually, she kept her hair in a neat bun very reminiscent of the 1960s—she always had “good” hair in my opinion, which she would still straighten slightly. I’m in my usual two pigtails. (Once our maid, Paulina, was trusted to fix my hair before school one morning while my mother dealt with an emergency, and she braided it into three plaits, two on the side and one in front to the side. I cried and refused to go to school until my mother returned. She quickly rebraided it so I wouldn’t have to go to first grade looking like a “pickaninny.” (But who said that? Did my father say that? Did he say that when she told him about it over dinner at the table, eyes twinkling; “Well, Junior, I guess she didn’t want to go to school looking like a pickaninny” and my mother pursing her lip in disapproval and my brother snickering).

And there’s our dog, Jag. Years later when we return to the States, I remember seeing my brother crying as Jag lay in the kennel weakly trying to eat a treat. And wow! I always liked tape recorders and radios! Oh man, I hit the jackpot that birthday!

figure 4. “Deidre’s Birthday No. 8 with Skipper,” purchased on eBay by the author.

figure 4. “Deidre’s Birthday No. 8 with Skipper,” purchased on eBay by the author.

They are just like you, yet they’re giving to a city of drama, a drama all their own. This is a true story, if not an actual one. Everything is projection and appropriation. That film was not, and is not, a film of me. It really is a filmed document of a Black child’s birthday, though not mine. I don’t have any childhood home movies. It is an orphaned film labeled “Deidre’s Birthday No. 8 with Skipper” that I had purchased on Ebay. And yet it could be me, my mother, my friends, and my dog evoking a stand-in for my missing girlhood (filmed) images. This small-gauge film, inadvertently rich in content, adopted me. I belong to the history it elicits.

The scarcity of images of African American daily life that instigated Castro’s project is being challenged by initiatives like the Great Migration. Professional organizations like the Association of Moving Image Archivists (AMIA) are giving greater attention to diverse media collections as the field expands via community archiving.{7} The digital data we gather through public digitization echoes the LFC project of seeing quotidian life, portrayed in home movies shot by African Americans (and others) as acts of self-representation and self-projection.

The films, videos, and audiotapes that we digitize can become something larger than family documents. They become greater than naïve verité documents when we recognize that they display awareness on both sides of the camera—awareness of the film format, the lighting or lack thereof, who is being looked at, how they are being looked at, and by whom; an intentional Black gaze.{8}

Sometimes, people appearing in the films we’ve scanned are more explicitly performers, such as in the case of “Iron Jaw,” a D.C. area celebrity who is depicted alternately lifting men by their belts with his teeth, chewing glass light bulbs, or running a razor across his inner lips (I cringe even now as I write this). The Montgomery family, captured on Super 8mm film by the families and friends for whom the family performed, are stars in their own right. They never miss an opportunity to dance—in the living room, on the beach, in the park, walking to the car —which is mirrored stylistically with frenetic, rapid-fire, in-camera, trigger-happy editing.

In another set of recordings, we see the McQueen family road trip as a reverse migration (The Great Vacation you could call it), recording their East Coast road trip down south for a family reunion (another popular topic). Chyron titles are dispersed throughout the footage to identify locations and to note the camera operator’s musings (“I think I like city life”) en route. When they arrive at a roadside motor inn, burnt-in text exclaims “WE MADE IT.”

Various excerpts, digitized and preserved by the Great Migration Home Movie Project.

I empathize with this urge to document and preserve. My family belonged to the era when “Black People On TV!” was an event in itself and a showing of a beloved Black-cast movie like Stormy Weather (1943) was particularly exciting. No matter how late, and no matter whether or not I had school in the morning, my parents would always wake me up to watch the finale of the musical, which featured a spectacular dance routine by the Nicolas Brothers wherein, introduced by bandleader Cab Calloway wearing a tailcoat conducting a swinging orchestra and swinging his baton and his “good” hair, they do flying splits on a gigantic staircase. Calloway is remembered and loved for his excessive performativity, his scat singing, and his late career media comeback by way of the film the The Blues Brothers (1980). But Calloway is underserved in music, popular culture, and film scholarship as a focus of complex questions about popular African American representation.

In a series of reels that came to the museum, Calloway gazes at the familiar faces of his children and his wife Nuffie. He films fellow band members, colleagues, and friends (including Lena Horne), and he surveys the landscapes, hotels, racetracks, and people that he encounters on performance tours of Jamaica, the Bahamas, Argentina, Uruguay, and other sites that led to a revitalization of his career in the States. We also see glimpses of the Calloway family home. Viewing his home movies takes me back to special times with my family watching the Nicolas Brothers, Lena Horne, and Calloway on TV in what seemed like the middle of the night.

The core of CAAMA’s home movie collection includes donations like the Calloway family films, home movies of international travel from the Michael Holman Family, 16mm films from architect J. Max Bond whose firm worked on the museum’s design, and films shot in Tulsa, OK, by Rev. Solomon Sir Jones (added to the National Film Registry in 2016). Art Historian Suzanne Smith brought in matchless group, ¼ inch open-reel audio tapes and a treasure trove of 16mm Kodachrome color films to be scanned over the course of several public appointments. Washington DC’s own Elder Lightfoot Solomon Michaux, who is featured in the films, established a network of churches along the east coast known as The Church of God.{9}

The 16mm Kodachrome color films were shot with wonderful cinematic style by Willie P. Jackson, whose films deserves further exploration. The footage mixes pre-Monty Python-esque cut out and collage animations with designed titles on cardboard and colored paper, with cotton balls, cut out type, sparkles, and trick lighting effects. These reels challenge the misperception that Black amateur films are atypical and thus extraordinary as they complicate viewers’ abilities to read them through a limiting sociological lens. The images shot by Black amateur film- and videomakers of homes, celebrations, and trips were intended to be shared, locally, in a sense, with family, friends, neighbors, and community without the burden of representing the race for those on the outside and of the painful pathological caricatures of commercial cinema.

THE PROPHET ELDER LIGHTFOOT SOLOMON PRESENTS HIS VISION. Digitized and Preserved by the Great Migration Home Movie Project.

In Baltimore, I sat through a real-time video session with a visitor as she murmured sotto voce expressions of suspicion about the digitization process. Would the images be stolen? Misused? I began to recognize these concerns of theft and misrepresentation as being characteristic of elder relatives from a different generation, one that is prone to be conspiracy minded.

Even as owners agree to share their films as part of the museum’s study collection, they frequently assert the right to protect their movies’ relatives. Even when participants have no connection whatsoever to their materials, or the individuals on screen, they often have specific editorial admonishments: Don’t show my father smoking. Leave out the adults drinking, wearing party hats, or acting silly. These editorial notes express a desire, I think, for a posthumous uplift narrative. The desire to sanitize the images carries with it a desire to be and to be seen as properly Black and upstanding for an imagined audience outside of the enclave. In this way, The Great Migration project allows African American images to be actively commonplace, providing mirrored portraits of Blackness rescued from denigration and obsolescence, but also sometimes distorted or remade by memories.

It’s a process of engagement. Archivists, whether inventorying a filmmaker’s elements in the basement or sitting with a client during a Great Migration appointment, as they point out their mother, their friends, or other loved ones, are performing a great deal of emotional labor. My colleague AJ Lawrence suggested to me that we are like foster parents to the films. And for someone like me, and like many of us who are now orphaned, we protect and parent these films, and then we let them parent us in return.

As a conservator, taking care of actual artifacts, of essential evidence, and of primary documents allows me the openness to continue to speculate and to conspire.

The finale of the LFC narrative reads as follows:

Extraterrestrials examine their ethnographic documentation of the planet Earth, the Lincoln/Archina films: “Based upon our evidence gathered in the 1920’s, inhabitants of the planet exist in family groups consisting of a coupled male and female with two or three handsome offspring. They occupy extravagant habitats. They are often involved in social, academic, and business rituals, as well as adventures and romantic triangles. We conclude from our findings that the Earth is a paradise occupied by brown and black-hued beings.

My involvement with The Great Migration project makes me think that the abducted films are hidden in plain sight, right here on earth.

{1} See, for example, a trailer for one of the first videos I ever produced. Ina Archer, “Trailer for 1/16th of 100%” (1996).

{2} Terri Francis,”Afrosurrealism in Film/Video,” Black Camera 1, no. 2 (2010): 5.

{3} Allyson Nadia Field, Uplift Cinema: The Emergence of African American Film and the Possibility of Black Modernity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 91.

{4} The name “Great Migration” was developed out of the graduate thesis work of Jasmyn Castro, when she was a Moving Image Archiving and Preservation (MIAP) student at New York University.

{5} Jasmyn R. Castro, “Unearthing African American History & Culture Through Home Movies” (master’s thesis, New York University, 2015), 35.

{6} Michael Boyce Gillespie, Film Blackness: American Cinema and the Idea of Black Film (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

{7} In November 2018 we inaugurated our Robert F. Smith Fund Community Curation digitization vehicle, a 24-foot truck outfitted with analog and digital video equipment, a film scanner, and an inspection bench, plus additional computers and decks to set up audio digitization stations. The first outing was a trip to Denver, Colorado outing was a trip to Denver, Colorado where the truck was stationed in Five Points, a historically Black community. The truck yielded 150 hours of digitized material—a volume that forcefully supports the efficacy and expense of designing and outfitting the truck, but the numbers also attest to the common occurrence of African Americans behind moving and still image-making equipment.

{8} I’ve been enjoying South Side Home Movie Project’s website which makes the films in their collections searchable by tropes, styles, and camera techniques giving weight to the intentionality of the makers.

{9} An early, enthusiastic, and enterprising radio evangelist, Michaux starred in a television program on the now defunct DuMont Television Network. Michaux and his wife Mary, known as Sister Michaux, presided over the church from 1919 until his death in 1968. Widely known as the “Happy Am I” preacher, he opened his CBS network show “The Happiness Hour” with the eponymous hymn as an elated chorus jumped and clapped in unison.