While his name is not a Hollywood fixture, Kevin Jerome Everson is quickly becoming recognized as one of the most consequential filmmakers working in the US today. Defying expectations audiences have about genre, form, and representation, his films are particularly celebrated in the film festival circuit and contemporary art world. Mid career retrospectives at Paris’s Centre Pompidou/Cinéma du Réel (2019), Harvard Film Archive (2018), Seoul’s Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (2017), and London’s TATE Modern (2017), as well as a solo exhibition at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art (2011) have highlighted work featuring many of the cinematic codes that are said to lend documentary its specificity as a mode, such as the use of archival footage, durational takes, and natural lighting. Yet many of his films stage scenes with nonprofessional actors such that they operate apart from conventions that have accrued around nonfiction filmmaking. His subjects are generally working-class African Americans, depicted engaging in quotidian activities. Critics who have written about Everson tend to emphasize the fact that his films circle back to a recurring theme of labor: his eight-hour film Park Lanes (2015) presents a day in the life of workers at a bowling equipment manufacturing company; Tonsler Park (2017) observes a community of people working at a polling station on the day of the November 2016 election; Island of St. Matthews (2013) shows a worker at a lock and dam in Columbus, Mississippi. Everson’s emphasis on labor, combined with his films’ often leisurely tempos, reorient us to the temporality of everyday work, work that lacks narrative momentum and as such is generally not portrayed in mainstream cinema.

In this essay, I wish to consider a related recurring theme across a range of recent films by Everson that has been less discussed than labor: athleticism. Like labor, athleticism foregrounds work, repetition, gesture, and skill, embodying a parallel cinematic repertoire of images. But more frequently than labor, athleticism crosses over into recreation, conveying what people do for fun precisely when they are not on the clock of capitalism. In turn, scenes of athleticism feel more joyful and carefree, seeming almost uncontaminated by ideology, which can be reinforced by the fact that Everson’s films don’t editorialize or appear to advance larger arguments. Yet images are of course never politically neutral, and passing time with bodies moving in space affords an opportunity to reflect on irreducible irruptions and remainders of the histories and stagings of race, gender, stereotype, and performance that figures of Black athletes conjure, as well as the boundaries between work and play that they scramble. Everson’s cinematic field powerfully refuses to yield to a Black brawns essentialism that persistently seeps through mediations of Black athleticism, often serving to uphold troublingly Darwinian accounts of the legacy of trans-Atlantic slavery.{1} Instead, Everson’s repeated return to athletic gestures and sporting events, I propose, invokes an even deeper return to another pastime: cinema itself—and more specifically to the aesthetic, ontological, epistemological, and political roots of early cinema, fascinated as it was by the medium’s nascent potential to capture, record, and study bodies in motion.

Explicit allusions to and reworkings of early cinema can be found throughout Everson’s films, inviting viewers to consider his work more broadly against the context of late nineteenth-century visual culture. As Jordan Cronk writes, a program of Everson’s shorts “cast four otherwise unrelated films in something like a study of twentieth-century American consciousness, linking both industrial evolution with corporeal decline, and traces of early cinema with unknown reaches of a medium in flux.”{2} Indeed, two of his films have been described as variations on the Lumière Brothers’ canonical 1895 silent film Workers Leaving the Factory. The Lumières’ films exemplify the observational potential lying at the heart of the cinematic enterprise, and have inspired a range of other artists, from Harun Farocki and Ben Russell to Sharon Lockhart and Andrew Norman Wilson, to remake Workers, as if to signal a rite of passage and a way to index changing times and concerns.{3} Everson pays his respective dues to these early pioneers in his seven-minute-long Workers Leaving the Job Site (2013) and yet again in Rams 23 Blue Bears 21 (2017). In Rams, an eight-minute single-take film that documents a mostly African-American audience leaving a football stadium in Salisbury, North Carolina, we watch as a steady stream of people walk out, almost in a single-file line, some directly looking at the camera, some directly looking away. As with most of Everson’s films, because it feels so observational (the camera doesn’t move, nothing extraordinary happens), it is tempting to assume we are witnessing an unscripted unfolding of a real event. As with most of Everson’s films too, however, one must hold such assumptions in check. Everson’s spectator can never be sure whether the image onscreen is staged or observational or some place in between.

from WORKERS LEAVING THE JOB SITE (Kevin Jerome Everson, USA, 2013). Courtesy of Video Data Bank.

Rams’s update of early cinema offers a literal transferal from one of Everson’s favorite themes (labor) to another (sport): a silent film is reimagined in a local stadium setting and in so doing builds a conceptual bridge to consider a more far-reaching interchange between sports and early film history. Taking Rams’s nod to Workers as a jumping-off point, I wish to reflect on other less explicit encounters between Everson’s films and formative, canonical moments in early film history. One goal of this essay is to demonstrate how the artist’s work alerts us to the racial dynamics that have been constitutive of documentary form yet have remained largely neglected in standard histories of American documentary. Scholars have astutely observed how complex racial dynamics serve as structuring absences in the broad evolution of cinematic techniques and modes—from narrative and sound to color and animation—but in such accounts, documentary tends to be elided, a slight effectuated by the deceptively benign, presentational aesthetics of early documentary photography, exemplified by Eadweard Muybridge’s protocinematic motion studies. The looming mediation of athleticism across such work cuts to the heart of documentary’s contradictions, pulled between expressive and managerial functions, condensing relationships among labor and play, invisibility and visibility, bodies and technologies.

from RAMS 23 BLUE BEARS 21 (Kevin Jerome Everson, USA, 2017). Courtesy of Video Data Bank.

In his authoritative analysis of Alan Crosland’s The Jazz Singer (1927), for example, Michael Rogin writes, “each transformative moment in the history of American film has founded itself on the surplus symbolic value of blacks, the power to make African Americans stand for something besides themselves.”{4} Rogin pinpoints these shifts in American cinema through four fictional films: Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Edwin Porter, 1903), which “marked the transition from popular theatre to motion pictures”; The Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith, 1915), whose length, narrative form, and fluid cinematic vocabulary “originated Hollywood cinema in the ride of the Ku Klux Klan against black political and sexual revolution”; The Jazz Singer, which became the “founding movie of Hollywood sound” and featured blackface performance at its dramatic heart; and finally, Gone with the Wind (David O. Selznick, 1939), which serves as an “early example of the producer unit system that would come to dominate Hollywood” that “established the future of the Technicolor spectacular by returning to American film origins in the plantation myth.”{5} More recently, Nicholas Sammond has identified a further such transitional moment in the history of cartoon imagery, unravelling the ways in which the emergence of the animation industry is also irrevocably entangled with blackface minstrelsy—most clearly demonstrated by Walt Disney’s introduction of Mickey Mouse, making his public debut in Steamboat Willie (1928).{6}

The “surplus symbolic value” of African Americans that Rogin and Sammond identify is thus acknowledged in relation to early fictional American cinema, yet documentary’s debts to such operations of racial exchange are largely uninterrogated. Since the mid-1990s, scholars focusing on nonfiction film have begun to envision a fuller account of how to place the practice within a “desegregated” film history. Scott MacDonald’s Adventures of Perception delineates extensive synergies between the oppositional strategies of Black cinema and avant-garde documentary, while Fatimah Tobing Rony’s The Third Eye provides an indispensable critique of the racial imaginary at the heart of the ethnographic impulse, particularly insofar as the anthropological project has more generally relied on the savage, raced Other.{7} To its credit, however, Rony’s wide-ranging account is not limited to the African American context; some of her most compelling readings draw attention to other loci of race and early cinema, from the Indigenous, titular, Inuit hero in Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922) represented as the archetypal “Primitive Everyman,” to French physician-anthropologist Félix-Louis Regnault’s time-motion studies of West Africans in the 1890s. Nevertheless, Rony’s important insights about the racial machinations of early cinema’s documentary impulse in a global, neocolonialist context form an umbrella framework within which to view the narrower, displaced slice of the histories of representation that I recall here. Indeed, it is my argument that Everson’s filmmaking—particularly when viewed through the lens of athleticism—indirectly leads our attention to the context of early American documentary and in turn to our critical failures to fully reckon with the histories of antiblackness that lurk in its frames.

Everson’s historiographic interventions unsettle what Michael Gillespie diagnoses as the uneven critical burden whereby “the fundamental value of a black film is exclusively measured by a consensual truth of the film’s capacity to wholly account for the lived experience or social life of race.”{8} Instead, Gillespie asks for a richer potentiality of the idea of Black film: “what if black film is art or creative interpretation and not merely the visual transcription of the black lifeworld?”{9} Everson’s filmmaking needs to be viewed as more than “visual transcription” as it frequently participates in a politicized, imaginative project of revisionist historiography as much as it documents everyday communities. Everson’s films mediate Black lifeworlds, not only real but also imagined and hypothetical, deflecting expectations tied to social reflection. While many of his films put untold stories of local and national figures on the record—as with his short film Round Seven (2017), which I will turn to later—the “record” being corrected is, crucially, never ontologically secure. Everson never distinguishes the real from the staged, and in the context of longstanding exclusions of African Americans from official histories, his refusal to formally settle for straightforward reflection becomes political.

One could understand Everson’s athletes—cowgirls, race car drivers, boxers, water skiers, foosball players, and so many more—as figures hidden in plain sight, representing the volumes of African Americans subjected to everyday practices of looking but not historical documentation. Importantly, the paradoxical encounter between the hypervisibility of Black performers (whether actors or athletes) and their symbolic exclusion from the historical record does not create an effect whereby the two extremes cancel each other out to leave us with flat indifference; they instead open up a charged field where the ordinary becomes imbued with uneven fluctuations among the hypervisible, the invisible, and the politics of the everyday all at once. Everson’s particular approach to filming sportive gestures and environments bears this point out, as American sports cultures have consistently staged dynamics of racial logics, offering scenes of displacement for their attendant anxieties. Persistent mediations of Black bodies “playing” configure opportunities for white spectators to make-believe the fantasy of a harmoniously integrated society, thus ignoring the racial injustices and embodied politics of “work” that co-exist with but are screened out by the virtuosity of athletic play. Rather than neatly packaging these lessons in narrative form or familiar documentary syntax, Everson prefers to leave these complexities aesthetically unresolved.

From this vantage point, Everson’s filmmaking invokes a cinematic past to help imagine a documentary aesthetics of Black film that moves beyond an embrace of representational realism to demonstrate how Black lifeworlds can offer more; they can form the foundation of art. Considering resonances in a feedback loop circling through a filmic span of over a century, I focus on the sportive ecology of images that cut across the present-tense moments of Everson’s films and the early moments of documentary cinema they conjure. The mutual imbrication of these early and late moments could be understood as a “new silent cinema,” characterized by parallel conditions in which short-form moving images circulate widely and the studio system is decentered as a mode of production.{10}

****

Conceptualizing an Athletic Cinema

As much as athleticism is recast in front of Everson’s camera, it is worth considering how it can be located behind the camera as well. At the 55th New York Film Festival in October 2017, Film Comment hosted a filmmaker’s chat with an unlikely combination of moving-image practitioners whose work had just been screened at the festival: Everson sat on stage in Lincoln Center alongside French auteur Claire Denis and the relative up-and-coming Norwegian filmmaker Joachim Trier. Everson was on hand to discuss his film Tonsler Park (2017), a feature documenting workers and voters at a polling station in a Black neighborhood in Charlottesville, Virginia on the day of the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Asked to discuss what new challenges each filmmaker took on in their respective films, Everson discussed the difficulties of shooting the film in a single day with a very tight turn around for the edit. He explained, “that was the first time I’ve worked that fast and athletically before… I like that kind of approach to filmmaking— just have it all kind of muscled up in one day.” Everson’s sporty metaphors are suggestive and worth mobilizing a bit further beyond the immediate context in which he used them. But what exactly would an athletic cinema entail? Some general propositions follow.

An athletic cinema can refer to a process-focused filmmaking practice regulated by discipline and constraints—much like the rules of sports. It would emphasize filmmaking as a bodily skill, requiring practice and endurance, through which a filmmaker-athlete gains strength and perfects his or her form over time. A web search for “athletic cinema” retrieves very little, save for a 48-hour filmmaking competition; but this is useful in that it emphasizes the practice of filmmaking under pressure, reveals the temporal and formal constraints that shape the activity, and calls attention to its competitive nature, the ultimate idea being to presumably see which filmmaking group succeeds best at creating within defined limitations.

figure 1. (L) ROUND SEVEN (Kevin Jerome Everson, USA, 2018). (R) THE RELEASE (Kevin Jerome Everson, USA, 2013).

figure 1. (L) ROUND SEVEN (Kevin Jerome Everson, USA, 2018). (R) THE RELEASE (Kevin Jerome Everson, USA, 2013).

The idea of athletic cinema might help us find resonances between filmmakers whom one would otherwise not associate with each other. Werner Herzog for example is a filmmaker whose practice like Everson’s crosses the boundaries between documentary and fiction, and, perhaps more than any of his peers, his remarks have aligned filmmaking with athletic practice. As Herzog puts it, “Everyone who makes films has to be an athlete to a certain degree because cinema does not come from abstract academic thinking: it comes from your knees and thighs. And also being ready to work twenty-hour days. Anyone who has ever made a film—and most critics never have—already knows this.”{11} Herzog’s comment highlights how an athletic cinema would also point to a certain instinctual paradigm that could be conceptualized in contrast to an intellectual one. For Herzog, filmmaking requires bodily knowledge over academic expertise. When asked to describe his ideal film school, he replied, “at my Utopian film academy I would have students do athletic things with real physical contact, like boxing, something that would teach them to be unafraid. I would have a loft with a lot of space where in one corner there would be a boxing ring. Students would train every evening from 8 to 10 with a boxing instructor: sparring, somersaults (backwards and forwards), juggling, magic card tricks.”{12} Herzog has described feeling a special affinity with Buster Keaton, who was famously a baseball fanatic—playing the sport in makeshift fields after lunch breaks on set, and wrapping up productions “in time to go to New York for the World Series,” as Keaton recalled in his autobiography.{13} Herzog notes that Keaton “is one of my witnesses when I say that some of the very best filmmakers were athletes. He was the quintessential athlete, a real acrobat.”{14}

Like Herzog, Everson often displays an aversion to academic theorization when discussing his work. When Terri Francis asked Everson to discuss elements of Afrosurrealism in his work, his response was representative: “y’all keep coming up with this stuff…you and Michael Gillespie. Y’all be wanting to talk to me, bringing up some new shit. Make me look bad. What the fuck is this? What’s Afrosurrealism?”{15} Everson displays a marked preference for keeping discourse grounded in the nuts and bolts of artistic practice: formal techniques, material support, the value of the lives of the subjects he records and the histories he uncovers.

Aligning Everson with a Herzogian conceptualization of athletic cinema perhaps disorients as much as it distills. The two filmmakers’ divergent gender politics, for example, differently inflect their athleticism: Herzog’s totalizing, “ecstatic” machismo imagines intensive, competitive training so vividly that one can almost smell the pheromones of the young men his film school would be training to box. This is at odds with Everson’s mode of athletic filmmaking, which is more processual than goal oriented and which interiorizes discipline more than pushing it to its extremes. These qualities that one might locate in Everson’s creative practice could also help to describe the nature of athleticism as a thematic tendency within his films, which refract stereotypical representations of Black male athletes as superhuman (think of Michael Jordan’s gravity-defying pose in hang time, forever iconographically imprinted by Nike), reorienting athleticism as environmental and phenomenological—revealing it as materially manufactured (in Park Lanes), as something we look away from (in Home, 2008, a single take of a scoreboard in Northern Ohio), as something we walk away from (in Rams), as an historically obscured event (Round Seven), or even as a gesture to be reinterpreted by dancers (The Release, 2013, based on an American football tight-end move).

****

Riding Horses, Tying Rope

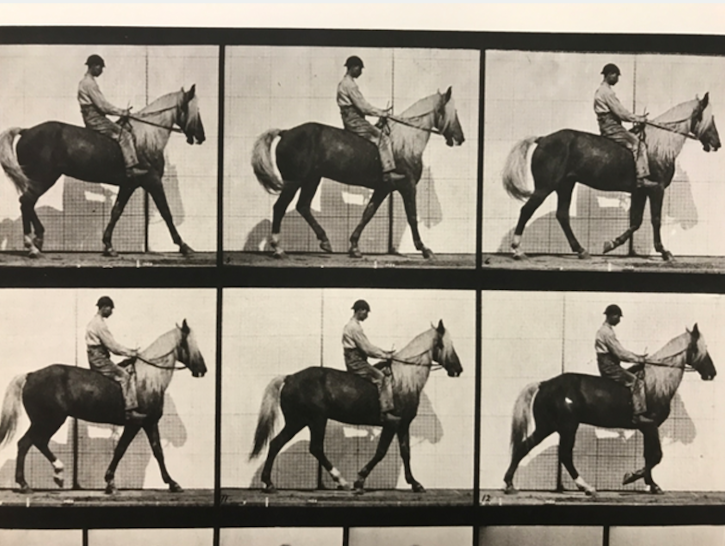

Everson’s moving-image studies thus summon and challenge an intertwined history between sports and documentary cinema, stretching back to the first moving pictures, which are particularly resonant with several of Everson’s films, especially in terms of their observational qualities, short duration, and frequent absence of synchronized sound. The spectacle of movement central to sports was particularly well-suited to the hallmark appeal of the new medium of cinema in the late nineteenth century: its ability to record motion. Indeed, Eadweard Muybridge’s innovative 1877–78 experiments using photographic sequences to document motion are generally agreed to be key predecessors in the development of cinema. These images depicted jockeys riding race horses to determine for ex-governor of California Leland Stanford whether equines ever keep all four legs off the ground while running. The animals, named Occident and Sallie Gardner, have been so overwhelmingly the focus of discourses about these images that it has hardly ever been remarked that the jockeys riding them were African American. The names of the horses in the studies are remembered while the names of the Black men riding them are, revealingly, all but forgotten to history. Racetracks might have been one of the few public facilities not governed by Jim Crow segregation laws after American Reconstruction, yet by not documenting the names of the Black jockeys, broader racial hierarchies override details of this history’s narrativization.{16}

figure 3. “Animal Locomotion, Plate 653.” (Eadweard Muybridge, 1887).

figure 3. “Animal Locomotion, Plate 653.” (Eadweard Muybridge, 1887).

In contrast to this, Everson’s quiet thirty-two-minute Ten Five in the Grass speaks volumes. Shot on 16mm film in 2012, the same year Fuji closed its film manufacturing facility, the film thus embeds in its very materiality a look back upon the history of the medium in a key moment of its transition. Not quite silent, the film contains very little audible dialogue, favoring subdued environmental sounds. It depicts Black cowgirls and cowboys as they prepare for rodeo calf-roping events. Shot in Lafayette, Louisiana, and Natchez, Mississippi, the film’s images emphasize repetitive gestures—swinging lasso, tying rope, grooming horses, taming bulls—what Everson would refer to as his subjects’ “internal language.”{17} Program notes for Ten Five often highlight the way in which the film re-envisions the folklore of the Western genre. Michael Gillespie’s comments about the film expand upon this significance:

The black western richly provokes the mythology of the American West and the idea of film genre as a historiographic imagineering by tacitly revealing how the narrative form has covertly borne a racial and cultural ideal. The genre’s classical themes of nation-building, the civilizing of savage lands, utopianism, and the discreteness of good and evil become refabulated as Everson draws attention to absences, disavowals, and the difference of a culture other than pale riders. Everson’s Ten Five in the Grass examines the craft of the black cowboy.{18}

I would suggest there is yet another layer of cinematic reflexivity at play in Ten Five that forms a mirrored inversion to the film’s relationship to the Western. If Ten Five points to the overwhelming absence of Blacks in clichéd, recycled cowboy iconography developed by classical Hollywood, it simultaneously seems haunted by the unnoticed presence of African Americans in Muybridge’s protocinematic studies of animal locomotion to which the film arguably bears an even stronger resemblance.

figure 4. TEN FIVE IN THE GRASS (Kevin Jerome Everson, USA, 2012).

figure 4. TEN FIVE IN THE GRASS (Kevin Jerome Everson, USA, 2012).

Beyond their shared captivation by the rhythms of bodily kinetics and their composition of repetitive, non-narrational gestures, Everson’s films, here and elsewhere, display a marked interest in the medium-specific elements of form—exhausting the length of the reel of film, for example, is often the constraint that determines what is included in a given shot and phenomenologically relays the passage of time. This athletic principle of duration structures Old Cat (2009), a single-take black-and-white film that depicts two men leisurely riding a boat on a lake in Virginia, as well as Erie (2010), a mesmerizing feature composed of seven eleven-minute scenes of different activities, such as krumping and fencing, each shot on a 400-foot roll of 16mm film. Situating Everson’s work against a longer American documentary tradition thus helps one discern the reciprocation of athleticism, discipline, and leisure that one finds both in front of and behind his camera. Indeed, viewing Everson’s practice as engaging in this kind of reciprocal exchange with the people he films ethically levels the set of looking relations so that—in contrast to many other works of contemporary art and nonfiction—the artist neither condescendingly regards nor uncritically celebrates the documentary subject.

****

Throwing Punches, Shooting Film

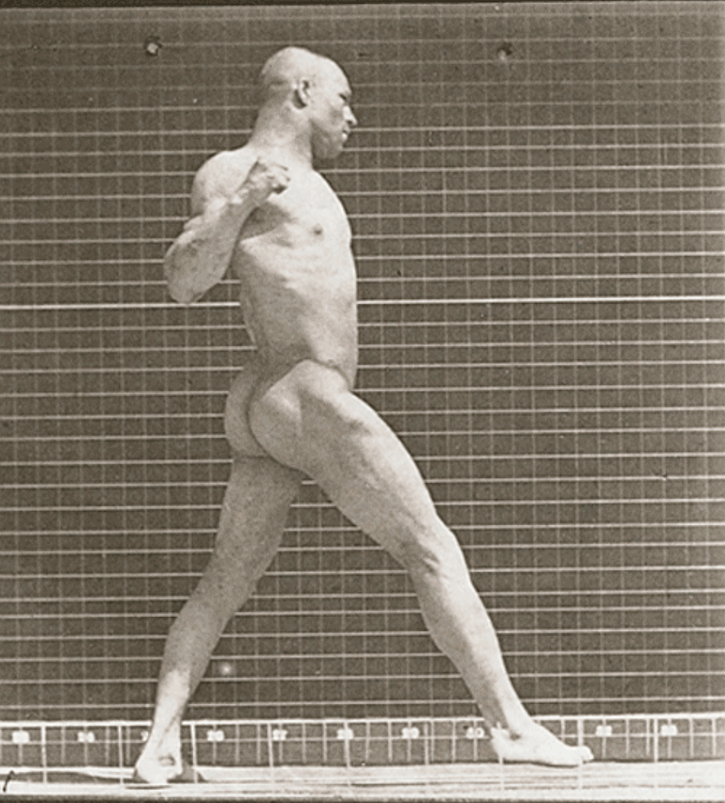

Everson’s focus on boxing in films like Ring (2008), Undefeated (2008), and Round Seven (2018) demonstrates how the legacies of early cinema might enrich our understanding of the reciprocity between the technical and the thematic, and in turn, the subject and the filmmaker. In discussing Round Seven, for example, Everson has noted the perfectly matched duration of a reel of film with the length of a round of a boxing match, and thus this confluence becomes an occasion to reflect on the connection between the materiality of film and the photographic inscription of athletic movement. Yet this is not nearly as coincidental as one might at first assume. As Jesús Costantino has argued, fight films were in fact constitutive of the evolution of film form. Boxing matches leave a palpable “trace within the structure of cinema itself, which continues to define the boundaries of film form to filmmakers, filmgoers, and film critics alike.”{19} Given the wide popularity of filming matches during the pre-narrative, cinema-of-attractions era, the sport “directly motivated the increased length of a single reel in order to simulate the length of a round.”{20} Costantino refers to Muybridge’s famous studies of boxing in the 1880s, after Muybridge had relocated from Palo Alto to Philadelphia, which, he suggests, more than any protocinematic experiments (or even the cinema of attractions) facilitated in “naturalizing” cinematic spectatorship. In the late nineteenth century of course, cinema was a new medium and cinematic spectatorship was a highly unnatural process, as the notorious account of the Lumières’ screening of Arrival of a Train (1896) at a Parisian café so usefully illustrates, regardless of its veracity. Extending familiar conventions of boxing spectatorship to his photographic sequences, images in Muybridge’s boxing series display varying camera positions to imitate “the many possible vantages from which a person attending a boxing match might see the action in the ring” and thus established a conventional mode of spatial orientation in narrative cinema.{21}

Formally, this is racially inflected on multiple levels. As Elspeth H. Brown notes of Muybridge’s boxing locomotion studies, “although the other ninety-four models were white, the anthropometric grid first appears behind the only model who was African American. It is as if the non white ‘other’ cannot be understood, scientifically, without the anthropometric grid, a technology for mapping racial difference.”{22} The grid had been used widely in nineteenth century ethnographic photography in misguided attempts to quantify racial difference in non Western bodies, and it is instructive that Muybridge first introduces the grid with his single non-white subject: Ben Bailey, a multi-race identified boxer based in Philadelphia. Not only was Bailey racially coded by placing him against this anthropometric backdrop, but he was also racially differentiated in Muybridge’s framing. Unlike the other photographs in the series, Bailey boxes alone and is visually isolated in the center of the frame. Constantino observes, “in the two series of Bailey, the frame no longer corresponds to presumed ring boundaries, but instead to a technological consciousness with a form and function not unlike Laura Mulvey’s account of the fetishistic close-up.”{23}

figure 5. “Man, punch” (Eadward Muybridge, 1884). Ben Bailey was the only non-white individual to be photographed by Muybridge during his human studies at the University of Pennsylvania beginning in 1884).

figure 5. “Man, punch” (Eadward Muybridge, 1884). Ben Bailey was the only non-white individual to be photographed by Muybridge during his human studies at the University of Pennsylvania beginning in 1884).

The inferentially racist spectatorial gaze of anthropometry that informed Muybridge’s experiments, coding its Black subject as an object of scientific scrutiny, manifested much more explicitly in another key flashpoint in the history of early documentary practices: with the Johnson vs. Jeffries prizefight match of 1910. Its reliance on what Rogin calls the “surplus value” of Blacks cannot be overstated. Filmed by an unprecedented number of cameras, with special lenses developed for the event, for a Fourth of July audience of tens of thousands, it was a cinematic event that as Dan Streible notes, “became as widely discussed as any single (film) production prior to Birth of a Nation.”{24} Rather than excluding the white opponent from the frame as in Muybridge’s images of Bailey, this media spectacle was the “event of the year,” staging a racialized clash between the Black heavyweight champion Jack Johnson and retired champion James Jeffries, nicknamed the “Great White Hope.”{25} Jeffries’ defeat, as many others have argued, mobilized racial anxieties that prefigured those soon to be unleashed by Birth of a Nation, including the nationwide eruptions of race riots and violent deaths that followed in its immediate aftermath.{26} It also led to the first instance of government-enforced motion picture censorship in the US, the Prize Fight Film Act of 1912, which forbade interstate shipment of fight films.

Jack Johnson, select archival footage, ca. 1908-1915.

I recall these histories to underscore cinema’s deeply racialized relationship to boxing and its impact on the future of the medium. Whether or not they are intentional frames of reference in Everson’s films, they recast his films’ significance, which are already characterized by a commitment to historical consciousness. Round Seven perhaps best exemplifies the ways in which these issues of race, film form, and history are cinematically triangulated. The film finds Everson revisiting his hometown of Mansfield, Ohio, a location to which his camera often returns. His Mansfield films often feature what he refers to as “re representations” of incidents from or related to his hometown, testifying to his interest in telling stories of people from there. The film’s central concern is a famous 1978 boxing match between celebrity boxer Sugar Ray Leonard and Mansfield local Art McKnight. Leonard was in the beginning of his professional career, having just won an Olympic gold medal in 1976. McKnight was not a household name, making this a significant event for residents of his Ohio hometown.

figure 6. Kevin Jerome Everson, Armond Richard, and Art

McKnight, filming ROUND SEVEN (2018).

figure 6. Kevin Jerome Everson, Armond Richard, and Art

McKnight, filming ROUND SEVEN (2018).

Round Seven’s images cut back and forth between Black screens; color shots of a woman walking in circles, holding up sequentially numbered round cards above her head in different parks and public facilities in Mansfield; current-day color footage of a young shirtless Black boxer with boxing gloves on, throwing punches solo; and black-and-white footage of a presumably present-day boxing match. The boxing images tend to be tightly framed to the point where the movement depicted often becomes abstracted. The different sets of images are held together sonically by McKnight’s narration of memories of the match, round by round, forty years later. These images disjunctively reinforce the temporal disparity between McKnight’s present-day narration and the event he is recalling— inevitably tainted by natural memory loss and selective recollection that occurs with the passage of time. Yet at the same time McKnight’s delivery resounds with the sense that the match has certainly been recalled on more than one occasion in the forty years since its passing.

McKnight begins by recounting how Angelo Dundee (Leonard’s boxing trainer, who also trained Muhammad Ali, George Foreman, and over a dozen world boxing champions) tried to keep him up the night before his match by phoning McKnight’s room multiple times. McKnight says, “I probably stopped counting at four times…. but what he didn’t realize is he wasn’t keeping me woke because I don’t sleep at night, no way.” McKnight recalls but graciously understates this foul play, before proceeding to reflect on being incarcerated in Ohio, and how fighting kept him out of prison: “I wasn’t interested in going to school, I was interested in doing anything to keep out of prison…. I could see fighting, that was going to be my way out…. Even then… would cost more to incarcerate me than educate me.” This is one of very few moments in McKnight’s narration that connects past to present, reminding the spectator of the historically constant racial discrepancies amongst those who are incarcerated in America, while framing boxing not as a leisure pursuit but an economic opportunity. Indeed this passage stands out in McKnight’s otherwise very detail-oriented, round-by-round recollection of his fight with Leonard. It is symmetrically closed by recalling how, in round seven, Dundee yelled across the ring to stop the fight, and then in a very controversial and unprecedented move, the referee proceeded to stop the fight. As McKnight puts it: “Never saw a fight stop—no standing eight count, no knockdown, no warning, nothing. Referee just walked in and stopped.” McKnight displays dignity and resignation about the situation, saying he doesn’t want to complain about something that’s forty years old and that he believes the person who deserved to win won—even though the fight was clearly called too soon and against the standard rules of the game.

Everson has explained that this is one of only three Sugar Ray Leonard fights for which archival footage does not exist.{27} It had been telecast on ABC’s Wide World of Sports but was cut in round three. Thus McKnight’s recollection provides a first-hand account for the historical record in the absence of any known surviving footage of the event. The distinction between the film’s poetic imagery and the account described thus further registers as an index of audiovisual histories that have been lost, and more specifically of racial injustices that have been swept from the record, given that the Italian-American Dundee effectively interfered in letting the fight finish as it should have. In revisiting these lost histories while framing their erasures, the importance of Everson’s project within a broader film historical trajectory encompassing early cinema’s vexed relationships to boxing and race comes into focus— asserting the humanistic value of representation while always simultaneously accommodating doubts about documentary’s epistemological foundations and limits.

from UNDEFEATED (Kevin Jerome Everson, USA, 2008). Courtesy of Video Data Bank.

This history also reverberates through Everson’s two short boxing films from 2008, Ring and Undefeated, only to be refracted, recalibrated, and perhaps ultimately set aside. Ring is one of several films Everson has made with found footage, in this case silent footage of young Black boxers practicing moves. Monica McTighe writes, “there is an awareness of the quality of images and the grain of the film. The beautiful young men’s bodies become moving works of art as they are lit by the film crew and move in balletic motion. Like his fellow filmmaker Steve McQueen’s work, Everson’s film speaks to the eroticization (but also the fear of) the powerful Black male athlete’s body in the context of spectator sports. In this film, the boxers’ bodies become dancers.”{28} The description included in its DVD packaging, presumably written by Everson himself, is short and sweet: “Ring attempts to exhibit the ‘sweet science’ of boxing in an elegant way.” What strikes me about these two descriptions is their resonance with boxing and early cinema: from the scientificity of Muybridge’s anthropometric documenting of Ben Bailey to McTighe’s description of watching bodies in motion to the eroticization and fear of the Black male athlete that were so integral to the Johnson-Jeffries match. The film itself features certain punches in slow motion, changing the “real” time of the image, much as one might say early experiments in chronophotography did. Yet it’s not so much that Everson is making a concerted effort to bring these fraught histories back to our consciousness; it’s more that in Ring and elsewhere he is trying to propose we have a different relationship to these images, images which over the years have been assimilated within a cinematic vocabulary that takes stereotype for granted. Critic Emmanuel Burdeau observes, “Everson can film boxing, baseball, car races… but competition isn’t what interests him. His eyes are not on the prize…. The athleticism of numerous films of Everson, the athleticism that is complacently associated with Black Americans, is therefore no doubt a ruse. His cinema doesn’t have that conquering vitality, his images don’t have that facile positivity.”{29}

RING (Kevin Jerome Everson, USA, 2008). Courtesy of Video Data Bank.

Perhaps this appeal for a different relation to the image is most neatly staged in Undefeated. In this one-and-a-half-minute, black-and-white, 16mm film, we see two Black men in front of a chain-link fence that is no longer standing upright, a visual signifier that this is an environment that care forgot. One man, on the left side of the frame, is throwing punches and lightly jumping in the air, as if practicing boxing moves. The second man, in the right side of the frame, has his back to the camera and has his hand in the hood of a car, of which we see the front half. The man on the left seems to be smiling as he jumps and punches, before he stops and looks down into the hood of the car. Both of these men are depicted in acts of doing things—one is practicing moves, one is presumably repairing a car. The film’s subjects occupy two separate sides of the image, each engaged in respective activities. As such, boxing has been displaced both from the ring and from the anthropometric grid (though the beaten-down, chain-link fence serves as an inviting metaphor for what has become of it). Both men are getting by and seem sure of what they’re doing. The spectator, on the other hand, is offered no such certainty and can only be left with questions. Are these two men friends who were trying to get somewhere when the car they were driving broke down? Is the man only throwing punches to keep warm in the Midwest cold? Is he smiling because he is happy, or is the smile a trace of a subject who knows he is being filmed? Is this a scenario Everson has stumbled upon or is it one he has staged? The film’s title would seem to suggest that the two men are keeping a positive attitude in the face of adversity. It could easily have also been the title for Round Seven, offering a succinct description of McKnight’s good spirits about his match against Leonard. But the title invites us to realize too that one is also “undefeated” if one was never competing in the first place.

Consideration of Everson’s films from the perspective of athletics—as theme, description of process, and link to a longer history of the cinematic treatment of antiblackness—throws into focus the abiding fascinations and anxieties related to performance, movement, and competition that sporting events animate across American culture. At its most elemental level, athleticism identifies a thematic preoccupation in Everson’s work, serving as a connective tissue to think across a range of the artist’s films. A large number of his films shift, and quite literally un frame, the terms of athleticism and their deep entanglements in histories of Black American representation in popular culture. Sporting in Everson’s cinema sidelines raced, gendered ideologies of competition, as well as the thrills and let downs enabled by teleological schema that divide athletic performers into champions and losers, instead opening up a constellation of gestures, social worlds, and unresolved meanings. The frame—and unframing—of athleticism expands upon Everson’s own provocation to consider how his approach to filmmaking reciprocates the qualities of athleticism that are emphasized in the scenes he records. In doing so, he models an ethically leveled generosity to his subjects, seeing them as worthy of representation and even more crucially as worthy of a cinema that isn’t formally constrained by the legacies of its misuses.

Thanks to Michele Pierson, the editors at World Records, and Madeleine Molyneaux for their insightful feedback on drafts of this essay.

{1} Matthew W. Hughey, “Survival of the Fastest?” Contexts 13, no. 1 (2014): 56-58.

{2} Jordan Cronk, “Kevin Jerome Everson,” BOMB, April 6, 2017.

{3} See Jennifer Peterson, “Workers Leaving the Factory: Witnessing Industry in the Digital Age,” in The Oxford Handbook of Sound and Image in Digital Media, eds. Carol Vernalis, Amy Herzog, and John Richardson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 598-619.

{4} Michael Rogin, “Blackface, White Noise: The Jewish Jazz Singer Finds His Voice,” Critical Inquiry 18, no. 3 (Spring 1992): 417.

{5} Rogin, “Blackface, White Noise,” 417-419.

{6}Nicholas Sammond, Birth of an Industry: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Rise of American Animation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

{7}Scott MacDonald, “Desegregating Film History: Avant-Garde Film and Race at the Robert Flaherty Seminar, and Beyond,” in Adventures of Perception: Cinema as Exploration: Essays/Interviews (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 10-80; Fatimah Tobing Rony, The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996).

{8} Michael Gillespie, Film Blackness: American Cinema and the Idea of Black Film (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 4.

{9} Gillespie, Film Blackness, 5.

{10} Paul Flaig and Katherine Groo, New Silent Cinema (New York: AFI Film Readers, 2015). See also Miriam Hansen’s influential essay, “Early Cinema, Late Cinema: Permutations of the Public Sphere,” Screen 34, no. 3 (Autumn 1993): 197-210.

{11} Werner Herzog, Herzog on Herzog, ed. Paul Cronin (London: Faber and Faber, 2002), 101.

{12} Herzog, Herzog on Herzog, 15.

{13} Buster Keaton with Charles Samuels, My Wonderful World of Slapstick (New York: Doubleday, 1960), 154.

{14} Herzog, Herzog on Herzog, 138.

{15} Terri Francis, “Of the Ludic, the Blues, and the Counterfeit: An Interview with Kevin Jerome Everson,” Black Camera 5, no. 1 (Fall 2013): 205.

{16} For representative accounts of these experiments, see Gordon Hendricks, Eadweard Muybridge: The Father of the Motion Picture (New York: Grossman, 1975); Noël Burch, Life to those Shadows, trans. Ben Brewster (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1990); Rebecca Solnit, River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West (New York: Penguin Books, 2003); John Ott, “Iron Horses: Leland Stanford, Eadweard Muybridge, and the Industrialised Eye,” Oxford Art Journal 28, no. 3 (2005): 409-428; Marta Braun, Eadweard Muybridge (London: Reaktion Books, 2010); and Allain Daigle, “Not a Betting Man: Stanford, Muybridge, and the Palo Alto Wager Myth,” Film History: An International Journal 29, no. 4 (Winter 2017): 112-130. For a fascinating, experimental cinematic account, see Thom Andersen’s Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer (1975).

{17} Kevin Jerome Everson, “Artist Statement,” Callalloo 37, no. 4 (2014): 799.

{18} Michael B. Gillespie, “2 Nigs United 4 West Compton: A Conversation with Kevin Jerome Everson,” Liquid Blackness 1, no. 2 (April 2014): 50.

{19} Jesús Constantino, “Seeing without Feeling: Muybridge’s Boxing Pictures and the Rise of the Bourgeois Film Spectator,” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal 44, no. 2 (Fall 2014): 68.

{20} Constantino, “Seeing without Feeling,” 67.

{21} Constantino, “Seeing without Feeling,” 69-70.

{22} Elspeth H. Brown, “Racialising the Virile Body: Eadweard Muybridge’s Locomotion Studies 1883-1887,” Gender & History 17, no. 3 (Nov 2005): 637.

{23} Constantino, “Seeing without Feeling,” 72.

{24} Dan Streible, “Race and the Reception of Jack Johnson Fight Films,” in The Birth of Whiteness: Race and the Emergence of US Cinema, ed. Daniel Bernardi (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996), 193.

{25} Gail Bederman, Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 1.

{26} See Susan Courtney, “The Mixed Birth of ‘Great White’ Masculinity and the Classical Spectator,” Hollywood Fantasies of Miscegenation: Spectacular Narratives of Gender and Race, 1903-1967 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 50-99; Dan Streible, Fight Pictures: A History of Boxing and Early Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

{27} Kevin Jerome Everson in discussion at ASAP Conference, New Orleans, LA (October 2018).

{28} Monica McTighe, “A Work Aesthetic: The Films of Kevin Jerome Everson,” Broad Daylight and Other Times: Selected Works of Kevin Jerome Everson DVD notes (Chicago, IL: Video Data Bank, 2011), 5.

{29} Emmanuel Burdeau, “Undefeated—Notes on the films of Kevin Jerome Everson,” trans. Bill Krohn, Drain 10, no. 1 (2013).