Documentary Says Amen! St. Clair Bourne and Black Liberation Theology

Jon-Sesrie Goff

In the absence of a singular set of shared rituals, communities of descendants of enslaved Africans birthed, instead, a creolized style of storytelling that privileged symbolism, synchronization, memory, and the spoken word. One of the primary sites for the reclaiming of these narratives is a selection of overlooked amateur and professional films that have been overlooked and largely remained outside of popular discourses and canonical records of cinema. In the 1960s and early ’70s, the interiority of African American lives was overwhelmingly neglected in popular representations in favor of the repeated tropes of reportage surrounding the civil rights movement and other reactions to white supremacy. These dynamics left little room to visualize practices of everyday life or to engage with institutions that protect and nourish Black culture. As the museum specialist for film at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, one of my main goals was to make sure that our film programs created opportunities for individuals to see themselves as part of a community and a lineage of ideas.

The Smithsonian’s mission to explore American history through an African American lens echoed my own aims to reconcile the disparate parts of “remembering” that jolt the principles upon which American ideas were built. At the same time, I felt the need to expand on the museum’s mission by asking: Who does the production, participation, and exhibition of a documented experience benefit if remembering isn’t a bold enough objective, if the intention of the program should be closer to liberation?; What role does religious life play in this dynamic?; What role does documentary play when it is documented or viewed outside of the experience and space it depicts? These questions challenged me to consider how programmers can re-present cultural moments, especially to audiences that see their culture represented in the cinematic works on screen. African Americans have struggled to create a theology of liberation within the larger practice of Christianity, which has been used as a tool of oppression. This same liberatory struggle for transformation continues to occur in the realm of image production as a way of repairing the visual trauma of decades of misrepresentation in the media and reinserting lost or forgotten works into the contemporary discourse of African American visual culture production.

figure 1. NMAAHC’s “A Changing America: 1968 and Beyond” addresses ideas of black liberation in daily life. Credit: Alan Karchmer

figure 1. NMAAHC’s “A Changing America: 1968 and Beyond” addresses ideas of black liberation in daily life. Credit: Alan Karchmer

Designed to engage both cinephiles and religious communities alike, Cinema + Conversation was the second interdisciplinary collaboration I developed between the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s (NMAAHC) Center for African American Media Arts (CAAMA) and the museum’s Center for the Study of African American Religious Life (CAARL). The first program, celebrating the remastered version of Daughters of the Dust (1991), sought to reimagine depictions of African spirituality. The second program titled “Let the Church Say Amen!” presented works by James and Eloyce Gist, and St. Clair Bourne, with the objective of highlighting the intersection of film and religious vocation. James and Eloyce Gist were evangelists who made films to accompany their sermons. St. Clair Bourne’s documentary, also titled Let the Church Say Amen! (1973), amplifies a number of narratives presented throughout the NMAAHC galleries in exhibitions.{1} For example “Power of Place” examines ten distinct African American communities, and “A Changing America: 1968 and Beyond” illustrates the activation of liberation ideology in daily Black life. CAARL’s director Brad Braxton noted during the post-screening discussion of this program that Verdict Not Guilty (1933) illustrates a desire for inclusive religious communities that embrace progressive ideology. We paired these works to contradict the stereotypical depiction of 20th century Black Christianity as either performative, as was the case in King Vidor’s Hallelujah (1929), or inherently conservative, as was the case in the 1944 US government propaganda film, The Negro Soldier. The films we screened situated Black spiritual experience within the historical forces and social movements of their time and embrace archetypal characters that can be considered to be social outcasts. The link between the Gists’ and Bourne’s films, I suggest, is an investment in a radical Black theology that seldom penetrated the secular entertainment genres of early African American cinema and was all but erased through dominant-culture-created images of civil rights era respectability politics. These prolific filmmakers, whose work sits between fiction and nonfiction and between art and activism, remain largely outside popular cinematic discourse, and as a result they are relatively unknown to most audiences.

For many people of African descent in America, Christianity has always been radical, and the presence of Africans fundamentally transformed the nature of religious expression in the Americas. For theologian Howard Thurman:

The conventional Christian word is muffled, confused, and vague. Too often the price exacted by society for security and respectability is that the Christian movement in its formal expression must be on the side of the strong against the weak. This is a matter of tremendous significance, for it reveals to what extent a religion that was born of a people acquainted with persecution and suffering has become the cornerstone of a civilization and of nations whose very position in modern life has too often been secured by a ruthless use of power applied to weak and defenseless peoples.{2}

The most common examples of the radical potential of Christianity are evident in the traditions of Black music, from the spirituals used by the enslaved as a tool for communication as people escaped along the underground railroad to the protest songs of the civil rights era. Yet cinema too contained the potential for, if not always the realization of, radical politics on a mass scale. As Thomas Cripps writes, “no other genre, except perhaps the American Western, spoke so directly to the meaning and importance of shared values embraced by its audience” than the race films of early cinema.{3} The films of the Gists’ and Bourne upset the power dynamic of cinema and Christianity. Film allows for a form of synchronization in African American storytelling. The desire to speak directly to the shared consciousness of an African American audience, within the context of their respective eras, usurps the need for translation. It also contributed to its neglect because the core issues in their works weren’t explicitly translated for general audiences. S. Torriano Berry, who reassembled the Gists’ work from fragments at the Library of Congress and began screening the works in 1996, felt the religious subject matter made it difficult to assert their importance as pioneering filmmakers. The program and discussion elicited a number of “call and response” engagements from the audience. Mostly comprised of members of the ecumincal community, this was an interplay between speaker and audience. This is one of the retained Africanisms in Black culture and a hallmark of African American storytelling and church tradition. In the context that they were exhibited at NMAAHC, much of the intended interplay between filmmaker and viewer remained intact.

from VERDICT, NOT GUILTY (James and Eloyce Gist, USA, 1933).

In preparation for our collaboration, we mined the canon of African American works that explicitly intersected with African American religious experiences depicting the organized, communal practice of faith. Rather than only relying on documentary films about African Americans and religion, it was important for us to examine works produced and directed by African Americans. (If we were to consider the impact of African American spirituality on African American secular culture, just about any film that engages African American experience would have been a viable option.) Throughout the African diaspora, religiosity has been a lens for the expression of racial identity.{4} Additionally, Black churches played a vital role in the exhibition of independent Black films, from Oscar Micheaux and the Gists’ to Haile Gerima, providing exhibition venues when movie theaters were inaccessible (or inhospitable) to African American filmmakers and audiences. Verdict Not Guilty, for example, was frequently screened in churches by the NAACP in support of the organization’s efforts to reform the criminal justice system of the 1930s.{5} However, our focus remained specifically on ways that filmmakers were critical of religion because we sought to provide ways of imagining African Americans as both Christian and radical.

In the wake of the civil rights movement and out of the ashes of urban uprisings across the nation, a young St. Clair Bourne found himself, among seminarians, challenging the very ideas of theology for people of African descent in America. Bourne attributes his desire to be a filmmaker to his coming-of-age during the civil rights movement and to his father’s profession as a journalist. Bourne said that he would:

Look at the reality of what was going on and observe what was being represented on television was incorrect. While most of the network documentary units weren’t, say, sympathetic, they at least were interested in telling the story. The problem though was that they were telling it from a different culture. They didn’t understand the people and just got it wrong. I felt that … I could tell the story better than the networks could. So I had to learn the tools of documentary filmmaking.{6}

figure 2. LET THE CHURCH SAY AMEN! (Bourne, USA, 1973). Images courtesy of Icarus Films.

figure 2. LET THE CHURCH SAY AMEN! (Bourne, USA, 1973). Images courtesy of Icarus Films.

In the same 2006 interview with Black Camera, Bourne explained that it was imperative that, along with many of his fellow documentary filmmakers in the late 1960s, we “identify with and are a part of the subjects we are filming …. We spoke out on behalf of them and us at the same time. I call this critical stance the ‘internal voice’ of our documentary filmmaking. Thus, one of the characteristics of my films is to express the internal voice of my subject, whether it is black or otherwise.”{7} Bourne’s commitment to situate viewers within the cultural context of subjects is evident in the opening title cards and early sequences of his Let the Church Say Amen!, which reprises some of the principle tenets of liberation theologist James H. Cone’s writing. They also evoke the critical thinking birthed from the practices of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, both of whom were at the fore of American consciousness and the margins of pervasive African American ideas of respectability that dominated most of the 19th and 20th century as a new generation sought to redefine the role of the church in the Black community:

from LET THE CHURCH SAY AMEN! (Bourne, USA, 1973).

These lines capture the ethos of Black Liberation Theology (also known as Black Theology) as defined by Cone in his 1969 text Black Theology and Black Power.

This work … is written with a definite attitude, the attitude of an angry black man, disgusted with the oppression of black people in America and with the scholarly demand to be “objective” about it. Too many people have died, and too many are on the edge of death. Is it not time for theologians to get upset?{8}

If “theologian” was replaced with “documentarian” perhaps we can access the frame of mind with which St. Clair Bourne approached his documentary work in the 1970s. Let the Church Say Amen! is a subjective look at the crossroads young people in the Black Power era were faced with when choosing a vocation and the various places where their ideas of social transformation could take root. Bourne’s life experience aligns with the protagonist here, who is forced to reconcile his identifying as a student, a militant, and a parishioner. Bourne’s film stages the urgent issues of Black identity in a changing America by confronting both a small rural town and a middle class urban community, exploring their varied articulations of spirituality and ministerial vocation. The systemic challenges that each community faced may have been shaped by white supremacy, but they also extend beyond to negotiations of intra-community aspirations and political differences. For Cone, Christian theology intervenes on these dynamics by creating a space in which Black people can actually see and be seen with complexity and agency. For Cone, the bible insisted upon approaching social questions from below, through the lens of the poor, the oppressed, and the marginalized, in order to determine how communities can move together from those positions. He believed that the Gospels were instructive in this regard.

In Amen!, Bourne establishes a typical weekend for the film’s protagonist Hudson “Dusty” Barksdale, first introducing him lighting a cigarette in a classroom at the Interdenominational Theological Center (ITC), a seminary in Atlanta, GA. The lecture he attends calls for “a fourth rhetorical element needed in sermonizing for delivering the word of God to desperately needy men with effective healing power.” His opening statement is punctuated by a mezzo forte “well” from the students. The idea that one’s vocation has the ability to heal “desperately needy” people appears here as an animating conviction for Barksdale and Bourne both, an idea Bourne spent his career exploring.

Further exposition can be gleaned from the choice of the seminary itself. ITC is part of the Atlanta University Center (AUC), the largest consortium of African American higher education institutions at that time, which also included Atlanta University, Morris Brown College, Clark College, Spelman College, and Morehouse College. The presence of an interdenominational seminary was important because all the other institutions were primarily divided based on denomination: Methodists at Clark, African Methodist Episcopalians at Morris Brown, Baptists at Spelman (Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary) and Morehouse (Atlanta Baptist Seminary). The ITC absorbs a critical discussion within the Black Community beyond the stereotypes attributed to—and the institutional silos perpetuated through—the various denominations that are typically understood through their social class affiliations and their proximity to white religious institutions. Morris Brown is the only institution that was privately founded, owned and operated by African Americans. ITC allows for intracommunity dialogue, developing a cultural and theological language that diverges from the parochial beliefs aimed primarily at white approval, and more particularly, at preserving white patronage. Students at ITC responded to the immediate needs, secular and religious, of activating the legislative advances of the civil rights movement into material gains for Black people in America.

Bourne and his crew of filmmakers would have likely blended into the student population at ITC. He was thirty years old at the time of the production in 1973, allowing him to move with relative ease and familiarity with the subjects throughout the film. Bourne was not adhering to the constraints of filmmakers who preceded him that documented Black life. The lecturer concludes, “if you ain’t got no preposition, you ain’t got no sermon neither” and following brief bouts of light-hearted responses, the class disperses with a hymn. This is not the seminary of the African American theologians that preceded them. With large beards, afros, and casual clothing, the men on screen share their thoughts on the role of Christianity in Black communities with the filmmakers over lunch. Later, on a basketball court with friends, Barksdale questions the relevance of his vocational training, trying to relate it to a future career focused on the liberation of oppressed Black people. Bourne wrestled with similar questions and strategies as a filmmaker, claiming that “I try to define the problem that my subject is experiencing and suggest a solution in the way the subject tries to resolve the problem. Even if they don’t solve it by the time you’ve finished the film, you’ve exposed the problem and shown how it did or did not work.”

Bourne links further still twinned pursuits that animate religious and documentary commitments. Evoking the spirit of Cone, Barksdale admits that the Black church is an institution with an evolving relevance, but that it remains the most meaningful space to pursue absolute transformation of self and society. Similarly, Cone wrote in God of the Oppressed (1975) that “Indeed our survival and liberation depends upon our recognition of the truth when it is spoken and lived by the people. If we cannot recognize the truth, then it cannot liberate us from untruth. To know the truth is to appropriate it, for it is not mainly reflection and theory. Truth is divine action entering our lives and creating the human action of liberation.”{9} For Bourne, Barksdale becomes a proxy through which he negotiate how best to place transformational, if transforming, discourses of truth in the service of social change.

from LET THE CHURCH SAY AMEN (Bourne, USA, 1973).

For Dr. Braxton, the film challenges viewers to confront what it means to live a life of calling. In the post-screening discussion, he suggests that,

The film is raising these boundary-transcending questions. What’s sacred, what’s not sacred. For me what’s sacred was the marvelous, rather brief, but intimate depiction of emerging black love. This couple walking in the park after a day trying to gure out the meaning of their lives as religious people. So the question of what it means to live a life of calling, what it means not just to render one’s life’s meaning by what feels good to me, by what’s convenient to me, but (with) some sense that we have something beyond us that’s laying a claim on us.

Like William Greaves, Madeline Anderson, and Stan Lathan, and other filmmakers making work for the WNET series Black Journal in the 1960s and 1970s, Bourne took formal risks in a deliberate effort to connect with Black audiences and reflect the cultural nuances of African American communities. Bourne describes their collective work as innovative because “editorially we took the position of the Black subjects in the documentaries we made. We tried to capture what they thought and what they did, and very rarely was that done by other filmmakers.” This approach aligns with what folklorist Michelle Lanier termed a “Spirit-centered ethnography,” which is described as “an ideology that intentionally moves the ethnographer through vulnerability (as defined by Ruth Behar) to a place of reciprocity and service.”{10} This mode of filmmaking serves a purpose beyond documenting or exhibition: it is an important tool in instigating thought within a community, and propelling and exposing those ideas to audiences outside of the community.

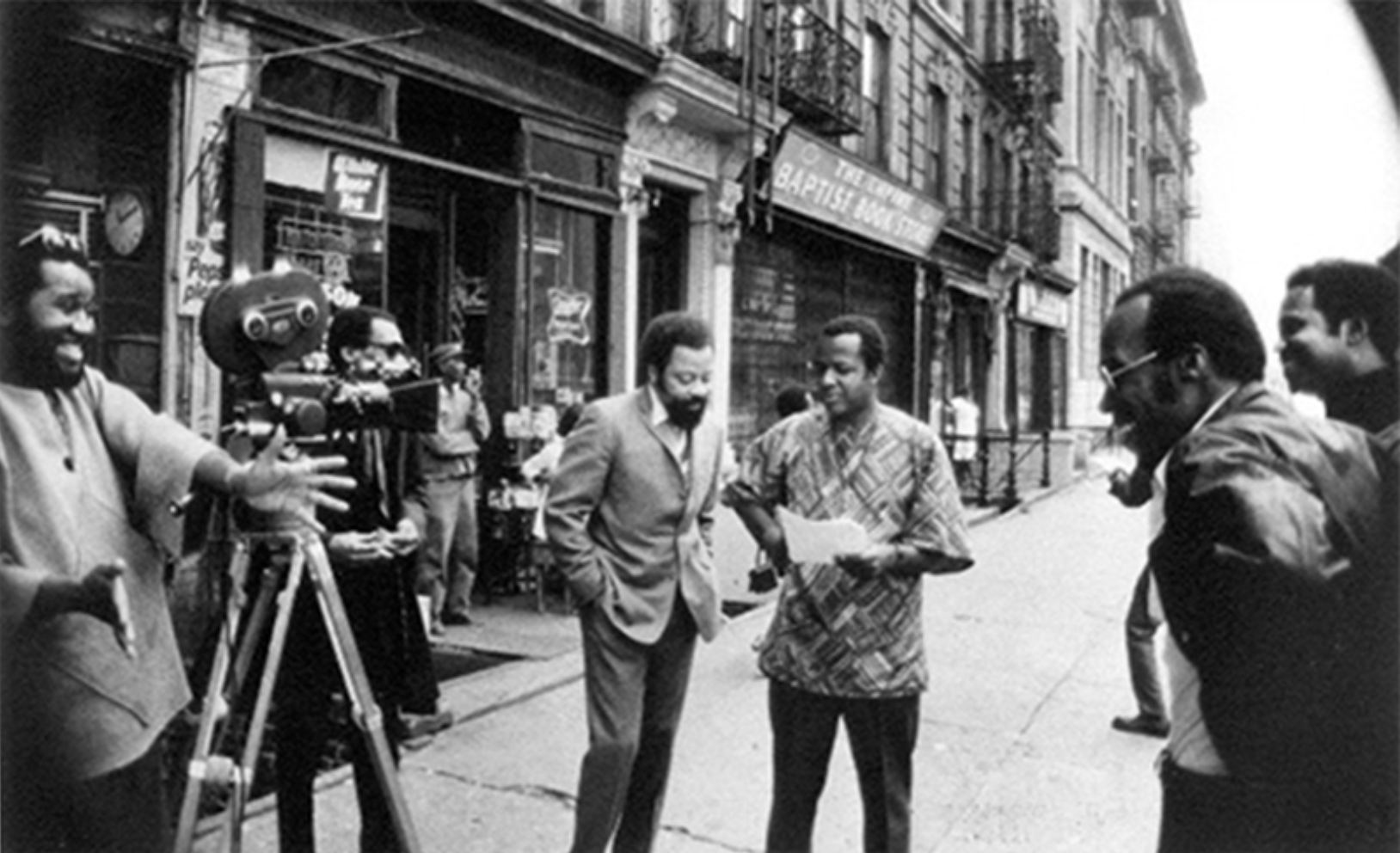

figure 2. William Greaves and Amiri Baraka in production for the WNET series “Black Journal.”

figure 2. William Greaves and Amiri Baraka in production for the WNET series “Black Journal.”

I can imagine St. Clair Bourne struggling with his own calling as a filmmaker during the production of this film. In a 2006 interview, Bourne spoke of his life’s work as “trying to take the form somewhere. Much like African Americans did with music, I’m trying to do with documentary.”{11} Because of how prolific he was, making over forty films in his thirty-six-year career, Bourne occupies an important space between his mentor William Greaves and African American documentarians of his generational cohort. After leaving Black Journal, where he worked with Greaves, he formed his own production company called Chamba in 1971 where Let the Church Say Amen! was their first independent feature production.

It’s not a coincidence that that production featured a young man in conflict with his chosen vocation, searching for a new language that adequately represents both the realities of being Black and the radical push he was hungry for. After all, the late 1960s represented a critical moment in Black documentary film, as the Kerner Commission Report was published in 1968. The Commission recommended that the media “integrate Negroes and Negro activities into all aspects of coverage and content,” and recruit more African Americans into broadcasting. In media, as in religion, would African Americans use their own agency to confront and change ideas of Blackness as a way to propel society beyond the racism that dominated the majority of the 20th century? Or would they, as the Kerner commission compelled, simply integrate into an existing broadcasting industry without transforming its structural logics? Echoing Bourne’s own ambivalence about the eld in which he worked, Cone, in an interview with Blackside producer Valerie Linson for the PBS series This Far By Faith, stated that he was “within inches of leaving the Christian faith, because that faith as I had received it and learned it no longer explained the world to me satisfactorily.”{12} How could these fields adequately address the agency of the oppressed in their struggle for justice? These questions still remain.

from LET THE CHURCH SAY AMEN! (Bourne, USA, 1973).

In the post-screening discussion, Dr. Braxton suggests that “we often have this myth of progress, but at least in (Let the Church Say Amen!) it’s harkening back to that particular moment of: What does it mean in a counter-public to have multiple generations engaging in the dance of sharing power and learning how to talk with one another? … How (do) traditions relate to one another and generations relate to one another as we try to create counter-publics that are pushing against dominant narratives?” Bourne’s lasting legacy, I suggest, can be located in his commitment to shattering the contemporary myth of progress. Before documentary can communicate information, it must first focus on building spaces, in form and material, in which people feel comfortable congregating. In the final scene of the film, a preacher warns them against “becom(ing) too mystical that we forget about the realities of life.” It’s a lasting message to end the film with, one that those entering the fields of documentary and ministry both would do well to heed.

Title Video: Let the Church Say Amen! (Bourne, USA, 1973) / Verdict, Not Guilty (James and Eloyce Gist, USA, 1933)

{1} The film program at NMAAHC, led by CAAMA, offers an opportunity to enhance a film screening by connecting works to historic and cultural objects in the museum’s collection. Objects are animated in new ways through their relationship to cinematic works. Programs are developed in relationship to the permanent exhibitions, items for the museum’s collection are printed in the program notes, and curators lend their expertise to the program discussions. This is important because of the dearth of African American history taught in most public schools.

{2} Howard Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited (Boston: Beacon Press, 1996), p. 42.

{3} Thomas Cripps, “The Making of The Birth of a Race: The Emerging Politics of Identity in Silent Movies,” in Daniel Bernardi, ed., The Birth of Whiteness: Race and the Emergence of U.S. Cinema (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1996).

{4} see Judith Weisenfeld, Hollywood Be Thy Name: African American Religion in American Film, 1929-1949 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

{5} Gloria J. Gibson, “Cinematic Foremothers: Zora Neale Hurston and Eloyce King Patrick Gist” in Pearl Bowser, Jane Gaines, and Charles Musser, eds., Oscar Micheaux and His Circle: African American Filmmaking and Race Cinema of the Silent Era (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 195-209.

{6} “St. Clair Bourne,” Black Camera 21, no. 2 (2006): pp. 9–14.

{7} Ibid.

{8} James H. Cone, Black Theology & Black Power (New York: Orbis Press, 1999) pp. 2-3.

{9} James H. Cone, God of the Oppressed (New York: Orbis Press, 1997) pp. 56-57.

{10} Michelle Lanier, “Home Going: a Spirit-Centered Ethnography Exploring the Transformative Journey of Documenting Gullah/Geechee Funerals,” Master’s Thesis, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, 2008.

{11} Dennis Hevesi, “St.Clair Bourne, Filmmaker, Dies at 64.” New York Times, December 18, 2007.

{12} “Episode 5: This Far by Faith.” Inheritors of the Faith. New York, New York: WNET, 2003.