Discerning the Call: A Let the Church Say Amen! Corner

Josslyn Luckett, Jon-Sesrie Goff, Reverend Alisha Gordon, and Sam Pollard

Like the expression itself, St. Clair Bourne’s first independent film, Let the Church Say Amen! (1973) lives somewhere between sacred invitation and political charge.

For the documentary’s central and migratory seminarian in training, Hudson “Dusty” Barksdale, the call to discern his ministerial path–from Atlanta to rural Mississippi to Chicago–requires much demographic and denominational grappling. And for the viewing congregants gathered either in the 1970s or now, the film asks not for a unanimous response, but it insists with an MLK-like urgency that Black people across faith traditions, across class and regional backgrounds listen to one another and co-creatively come to terms with the most productive path forward, away from chaos and toward community.

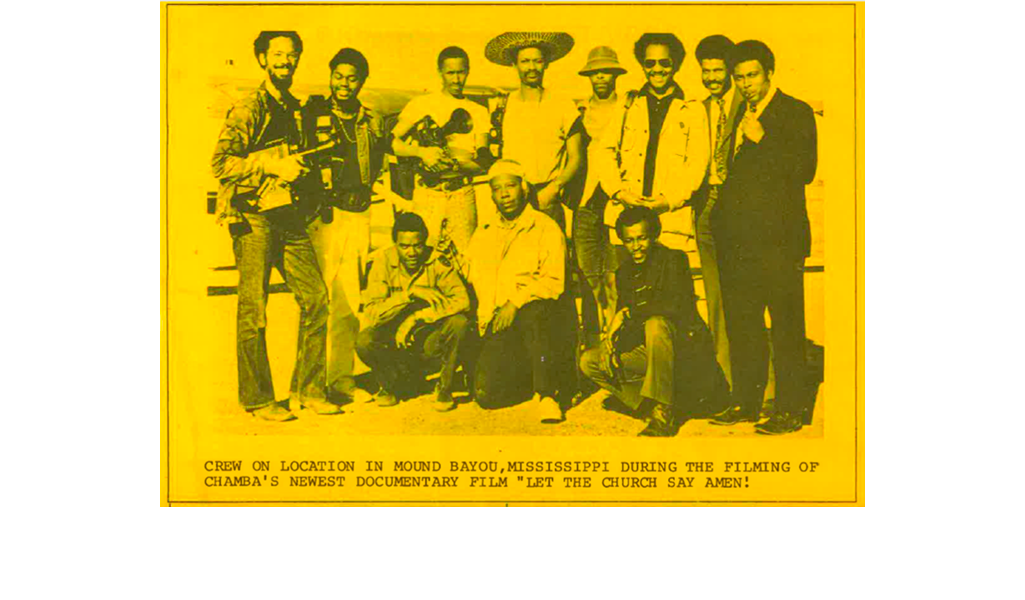

“He was always about community,” Sam Pollard repeated several times about “Saint” in our recent public conversation following an NYU screening of Let the Church Say Amen. Pollard, who deems Bourne one of the three most important people for his own filmmaking career, offers: “as a filmmaker of color, (Bourne) kept the community energized and kept us focused on our mission to tell our stories.”

Born in Harlem, St. Clair Bourne’s four-decade career began as an associate producer under William Greaves on the groundbreaking public affairs television series, Black Journal (1968-1977). His productions included documentaries on legendary African American figures such as Langston Hughes, Gordon Parks, Paul Robeson, and Amiri Baraka. Yet, to hear it from those who knew Bourne, a key aspect of his own legend was his commitment to mentoring young filmmakers, offering personal guidance as well as institutional support through his founding of the Black Association of Documentary filmmakers (originally boasting branches on both coasts, BADWest is still thriving in Los Angeles). The motivation and inspiration Bourne offered generations of filmmakers was, to crib from the title of his Baraka documentary, in motion throughout this conversation, energizing the panelists and the audience gathered to reflect on Black independent filmmaking and Black theology in ways not often encountered in academic settings. The experiential testimonies on Bourne that were offered by Pollard were matched by the grounding presence of Reverend Alisha Gordon of The Riverside Church and Jon-Sesrie Goff, who offers ways to bridge the historical and theological questions Let the Church Say Amen! provokes.

– Josslyn Luckett

****

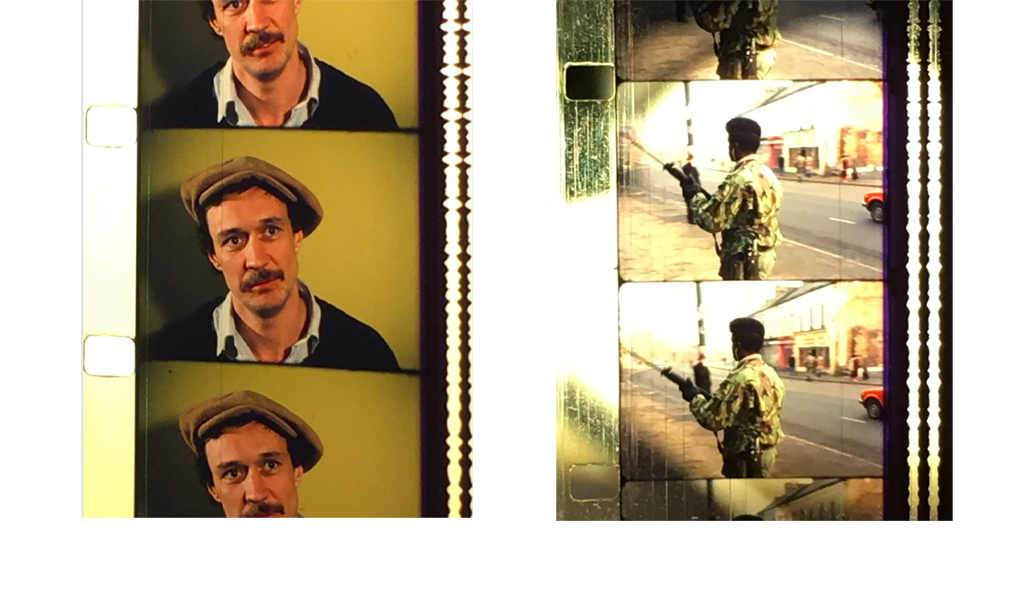

Josslyn Luckett

The first thing I think about when I watch this film made in 1973 is this East Coast versus West Coast of Black independents. We have this group at UCLA that’s also coming up in this late ’60s early ’70s moment. And I see both camps taking on similar issues of Black spirituality in relation to Black nationalism and where those two threads come together. We have films like As Above, So Below by Larry Clark which is within the same year, in 1973. And it’s on the surface a film about a group of Black insurgents, but there’s a really important scene in the Black church in that film. And one of the most evangelical, hand-waving people ends up being one of the insurgents later in the film.

It’s interesting to see that both of these groups of independents are grappling with these issues. But also of course in Black theology, James Cone is writing Spirituals and the Blues (1972) and he is also grappling with this sacred and secular piece and how it impacts our lives in this moment, right after the assassinations and when people are dealing with so much loss.

figure 1. AS ABOVE, SO BELOW (Clark, USA, 1973).

figure 1. AS ABOVE, SO BELOW (Clark, USA, 1973).

We have all the Black women writers coming up and talking about spirituality, Alice Walker, all those folks. So, it’s just such a fraught and amazing time. And Bourne’s Amen!, which on the surface feels like, “Wow, what was he doing?,” in that it seems kind of different from other stuff that he did, really is of a piece with so much going on culturally, spiritually, politically at that moment. That was my first thought to bring some context.

But I would love to know from each of you…I would love to know from you, Sam, since you knew him and worked with him, do you have memories of what this film meant to him?

Sam Pollard

I knew Saint from 1980. I find this film in keeping with Saint’s philosophy, both politically and socially, you know, he was always challenged to look at the community, the Black community in so many different ways. We had done The Black and the Green (1983) where he went with some African-Americans to Northern Ireland. Saint’s always challenging the perspective. He is looking at this young man who is going through theological seminary and trying to understand how to grapple with religion at the same time he’s looking at the notion of the old versus the new, the young man in the church, the young man challenging the older members of the congregation.

For me, this is in keeping with Saint’s approach to filmmaking. He never had just one single perspective. It was very complex perspectives. When you talk about the spirituality, it reminds me of the first film I worked on as an assistant editor for Bill Gunn, which was dealing with the same thing in another level, you know, spirituality and sensuality at the same time. That was in ‘72. So, Amen! was in that same milieu. So Bill Gunn and Larry Clarke and Charles Burnett, they are all in that same milieu where they never had one sort of defined perspective. It was always very complex and layered and that’s what I see when I see this film.

Jon Sesrie-Goff

I’m incredibly biased.

(Laughter)

I’m looking at the film from the perspective of the present. I find considerable overlap between theology and independent documentary filmmaking. And I think that in the same way that Black liberation theology demanded that Christianity speak to people living in the margins, speak to oppressed people, speak to Black people, I think that we are now in 2019, after the pendulum has swung towards prosperity in independent filmmaking that we need to demand that our independent and nonfiction films speak to people on the margins of life who are often the subject of the works.

So in this work, I see something amazing colliding. I see this impetus and from my research, St. Clair Bourne speaks about there not being any sort of lineage of Black born documentary that he had to be beholden to. So everyone of this era for me is breaking new ground. There’s not as many ties, whereas within theology we see a conflict around, “What does it mean if your ultimate purpose is liberation of people?”

So, what does that mean in your work despite what industry you may find yourself in? Often when I watch this film, I replace the calling to ministry with filmmaking. Or whatever other space I may find myself in. And really questioning, how in this moment can I use these tools to not become so mystical and detached, but to really speak to people, to be amongst people? And that’s the way this film is shot. I feel like it’s a very interactive experience, which by the way is the buzzword for grant applications now.

(Laughter)

So make sure films are interactive. So it’s something that can’t be disingenuous. It has to emanate from a space that serves someone else.

JL

Alisha, you might want to say something about that. I’m so fascinated with this film in terms of our protagonist’s call to ministry, his pastoral encounters, I think both in the South and the North, how did that strike you watching it?

The Reverend Alisha Gordon

Yeah. It is really interesting to watch as a clergyperson. Barksdale says in the film, “ministry is not what I thought it was … It’s not as utopian,” and we are, like, light bulb!

(Laughter)

But I think that was what is important about Barksdale’s narrative. In the film we see him going from this place in Atlanta (I’m an Atlanta native), and going to Mississippi, going to Chicago, and it was the exposure to different theologies, even different sounds, different spaces that helped him better understand what was happening, and which ultimately helped him better understand how Black people were connecting to larger movements, or the absence thereof.

I thought it was really interesting that the Pastor who picked him up in Mississippi said something like “we have always been Black.” That’s a different context than when you talk about people who have been Black and they are fighting for — they have a constant civil presence in their day-to-day lives. So, I really took to him as a character as someone who is clergy, someone who has been in seminary, someone who has heard a call and then you get exposed to all the things that it means to answer that call and then begin to question.

And not questioning to move away from, but a question that actually draws us closer. It makes us more refined in thinking about what we are doing as people of faith, whatever that means for you.

JL

Jon, can you talk a little bit more about why you suddenly became so drawn to this film?

J S-G

I became drawn to this film in my previous job at the Smithsonian Museum for African American History and Culture. I was the film specialist, and I worked in the curatorial department. And this was one of the films in our collection. And although there weren’t that many moving image works, I equated myself with the three hundred or so titles we had. And this one stuck out because my father is a minister who went to seminary around this era. He actually went to undergrad in the Atlanta University Center in the late ’60s. So when I watched it, I’m like, “Was that you, Dad?”

(Laughter)

So, I’m always challenging the status quo in terms of Black faith and even with my film that I have been in production on for the last five years, After Sherman, there’s continuous questions around, “is Christianity speaking to the modern needs of Black and oppressed people?” And “is participation within the institutional constructs of religion sort of passé and not radical?”

AG

That’s good. That’s good.

(Laughter)

JL

That’s beautiful.

SP

Alisha might know the answer to that.

AG

No, that’s a really good point. And I think he is wrestling with that, because there’s this conversation when they are at lunch — how do you reconcile being a marginalized person, a person who is experiencing oppression, and who is deeply engaged in a Christian faith which is filtered through this White lens, talking about what it means to be part of this White religion?

A marginalized person who is oppressed on every side, who is engaged in a Christian faith which has been interpreted to oppress you further, and engaged in an institution that by name is a Black institution, should be about liberation of people and often is. But in order for you to thrive in the institution, you have to subscribe to White ideals.

So there’s this whole thing you have to reconcile as a person of faith, as a Black person. And I think that is conveyed really well in the film. And I think what Jon is getting at about the modern understanding of the Christian church that proclaims to be liberators — How can you do that and live into capitalistic ideas? You see this play out with the pastor in Chicago in the film. He wants to feed the hungry, and do all the stuff. But he doesn’t have the capital or resources.

Our members, this model of membership-driven giving is responsible for ensuring that the church has what it needs to do its job. But our members are oppressed, marginalized people who can’t find work, who are rubbing two nickels together to make ends meet. So how do we reconcile those things? And I don’t necessarily … well, I have some answers. But I think the most important thing is we actually lift those questions up and wrestle with them.

from LET THE CHURCH SAY AMEN! (Bourne, USA, 1973).

JL

Jon, can you do some exegesis on the incredible scene that transitions from the club into the church?

J S-G

I think it’s become so common now that we don’t even recognize that juxtaposition as being something radical, and hearing them grapple with Barksdale’s presence in the nightclub as a man of faith in the subsequent scene.

For me what’s exciting, going back to St. Clair Bourne not being beholden to a particular filmmaking legacy, is that within the opening scene Bourne is already breaking all the rules. He breaks that 360 degree rule out of the gate to give a full view of the space. How that makes you feel as a viewer is important. Someone talks about this as Black storytelling not using the same Anglo or European language of cinema, because it’s not the language of the people you are trying to connect to. I think that in many ways, he’s honoring traditionally Black or African styles of storytelling out the gate? Even in the music and some of the tonal qualities of it with the Mississippi group, I think those things are really important. You even hear it in the high church in Chicago when they are trying to emulate the more Episcopalian performance of singing, and yet you can still hear the blues. I think even Bourne’s selection of music is so on point throughout the film. That’s what’s in the frame for me.

JL

Do you have questions for each other?

J S-G

I have a quote from Sam.

(Laughter)

It’s from Bourne’s obituary in the Los Angeles Times, where Sam says that “St. Clair Bourne re-energized and refocused what my mission should be as a filmmaker to document the African-American experience and make people aware that it’s an important part of the American experience that can’t be denied.” Those are your words.

(Laughter)

I am just curious in what ways Bourne has energized your career and your practice?

SP

I think it goes back to what you were saying. When I think of Saint, I think of him being a trailblazer in terms of shaping how films can be made from the African-American perspective. And I would put into that same category Bill Greaves. Where, again, these are filmmakers who are saying “we are going to challenge the perspective of how you see us and we are going to layer it.”

So when I was first introduced to Saint in 1980, I had been in the business seven, eight years and I had basically thought that as a person of color, I should not have that apply to my filmmaking. I should negate that and if I were asked “Do I want to be a Black filmmaker or a just a filmmaker?,” I would respond that I just wanted to be a filmmaker or an editor at the time.

When I met Saint, we were working on Chicago Blues (Big City Blues, 1986) and we would have these long conversations about responsibility as persons of color and as African-American filmmakers to our communities. And I’m sitting there editing this footage with all these Blues musicians like Billy Branch. And I started to understand that my agenda was the same agenda that Saint had. Every film I touched from that point on had to be about our experience and figuring out a way to articulate it in a similar way that Saint was trying to do.

He became a major personal and professional role model for me as a filmmaker in his helping me understand that. It’s interesting what Jon was saying about that 360 degree shot that Saint does in Amen!. That’s what he was doing all the time with his films. Saint was always grappling with and breaking down these norms of what filmmaking should be. And as an independent filmmaker, understanding the struggles to make independent films, the struggle to finance films, he was always dealing with that, but he was always dealing with how to always find the next layer and the shaping and telling of stories.

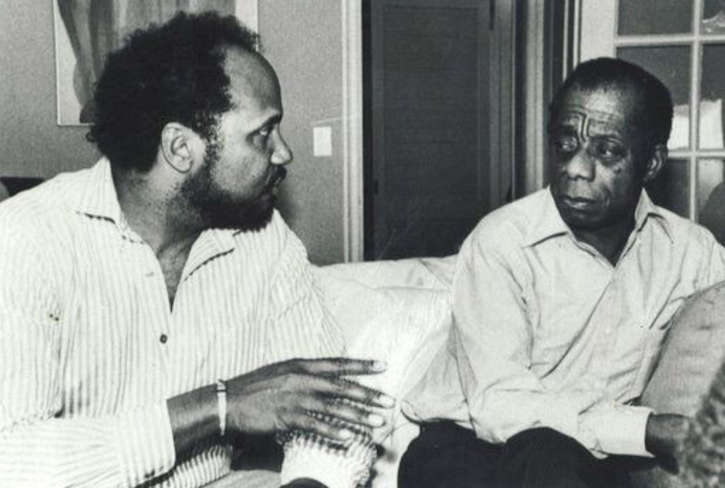

I worked on Black And The Green and Chicago Blues, even his film In Motion, that to me was a breath-taking film and looking at a man who was very complex, a phenomenal poet, but also had levels of contradiction. Saint was always dealing with that in his material. He’s the pinnacle for me in terms of what I always aspire to, and what I still aspire to as a filmmaker.

from THE BLACK AND THE GREEN (Bourne, USA, 1983).

J S-G

I took this statement by James Cone and interjected filmmaking into his theology statement. Cone says in the preamble of Black theology and Black Power that “this work is written with a definite attitude. The attitude of an angry Black man disgusted with the oppression of Black people in America and with the scholarly demand to be objective about it. Too many people have died and too many people are on the edge of death. Is it not time for (filmmakers or) theologians to get upset?”

I think that’s something that I’m constantly grappling with, and that my colleagues are grappling with. It’s this desire to exist within the academy, to exist within this filmmaking industry, and then to maintain a level of professionalism that requires you to be objective around suffering. And often the suffering of, you know, your people, your family, your community. I don’t think that’s fair. I think that we know in this day and age one hundred-plus years after the invention of the camera that every film is subjective. The second you point your camera, all objectivity is out the door. So why can’t young Black filmmakers be upset in their practice? Beyond the funding issues, why can’t you just be upset about the content that you are forced to engage with? I think that using the very powerful tool of the camera that other people have manipulated for their own means, I think we can continue to be radical as St. Clair Bourne was and using it as a tool of empowerment and liberation.

JL

That’s beautiful. Like all of you, Bourne was a filmmaker, a film educator, a mentor, you know, with his Chamba Notes, I guess there was the BADEast and the BADWest. All of these organizations, the curating and community-gathering that they did, it’s so multidimensional. It isn’t just about the filmmaking, but all of that gathering work is what I think he seemed to be about.

SP

Well, he was always about the community. That was the part of his mantra. As you were saying, he had Chamba Notes, he started BADEast, BADWest. He was always about community. He wanted to make sure as a filmmaker of color, he kept the community energized and kept us focused on our mission to tell our stories. He was always about that. Even when he was struggling, and sometimes Saint was in the ’90s — he was struggling to get films made and get funding, but he was always, always committed to the mission. Always. Always.

figure 3. St. Clair Bourne and James Baldwin during the making of LANGSTON HUGHES: THE DREAM KEEPER

(Bourne, USA, 1988). Courtesy of Judith Bourne and the St. Clair Bourne Archive.

figure 3. St. Clair Bourne and James Baldwin during the making of LANGSTON HUGHES: THE DREAM KEEPER

(Bourne, USA, 1988). Courtesy of Judith Bourne and the St. Clair Bourne Archive.

Audience

I find the connection between the filmmaker and the theology such a beautiful metaphor. And I find that as a filmmaker, I have to stop and ask myself questions about how I feel about filmmaking and what I’m trying to show. And it took me years of asking myself questions whether I was thinking like they wanted me to think and create, or whether I was thinking the way I wanted to be angry.

SP

The only thing I would say is that for young people who are growing up in this industry, they sometimes struggle to find their voice. And sometimes your unique voice is angry, and being able to express that takes some time.

Now some people find that immediately. Saint … Saint had that. He had that when he was at Columbia. He was at Georgetown, when he was in the Peace Corps. Saint had that because he grew up in an environment where that was part of what he was learning in terms of his sense of self. For me, it took until I was 30 to start to grapple with that and get that, because I had bought into the notion of the American melting pot, which Saint had rejected. It took me until I met Saint to realize that I needed to reject that, too. Some filmmakers have it immediately and sometimes you have to grapple with it and find it.

AG

Just to theologize this a bit, I think you are absolutely right. There is the connection between the two words filmmaker and theologian. But I think it’s important for exactly what is being said about the shared experience. Using our experience — theologians talk about this all the time. Experience is often the first thing that we have to connect to God and connect to our faith. To not do that, to resist using our experience is actually inflicting violence on ourselves and to the people who are waiting to hear our stories. How do we think about how our own personal faith formations or even our moral formations when we are often told we have to parse ourselves apart? I think good filmmaking and good theology causes that stuff to meld back together.

Audience

I’m just so impressed with the camerawork. It’s so intimate and it is hard to believe it’s nearly fifty years old. It’s just so fresh and you feel like people are just so comfortable. The intimacy and the engagement really comes through the camerawork, and also the attention to sound between the cadences of the prayers and the music and conversation.

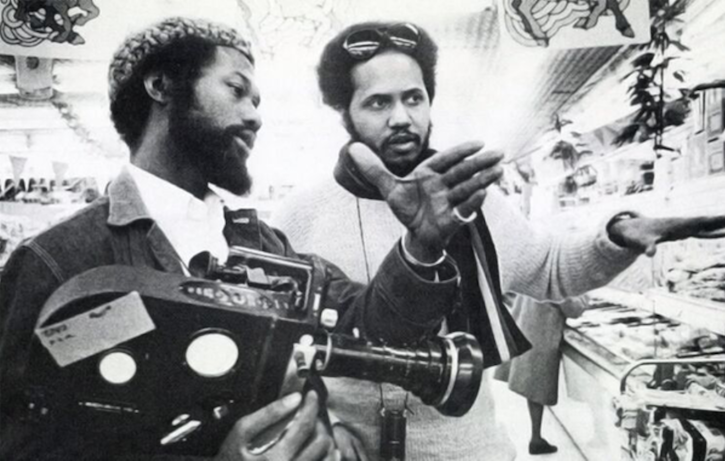

SP

I’ll say this. I know all the people who shot that stuff. Doug Harris, Leroy Lucas did the camerawork, Lucas and Ron Long did the sound. What’s fascinating is Saint had worked with all of them before. And as we all know, filmmaking is a collaborative process. These were very good cameramen. And Ron was a very good sound person. So they were able to be there in the moment and capture it. But the other thing that documentary filmmakers know is that you need to be able to have the people that you are shooting trust you, trust you and believe in you and give you access.

So obviously there was a tremendous amount of trust that developed. I don’t know over how much time. But it was there so they could get intimate, because that’s really good camerawork.

Audience

People felt free to be in conflict with each other.

SP

They could be themselves and the sound quality is excellent for a film like that, which is something that young filmmakers should learn from. But it’s that kind of thing you need to be able to have your subjects feel comfortable with you. I don’t know what Saint did, how long he spent with them, but they felt comfortable and gave them the access and the ability to feel like they could be in there. And the people being shot didn’t feel like “Oh my God, there’s a camera there.” You don’t feel that at all which is amazing. Even back then, that’s amazing.

figure 4. Leroy Lucas (L) with St. Clair Bourne. Courtesy of Judith Bourne and the St. Clair Bourne Archive.

figure 4. Leroy Lucas (L) with St. Clair Bourne. Courtesy of Judith Bourne and the St. Clair Bourne Archive.

Audience

Could you elaborate on that for a minute? What was it about his personality? It made me wish I had known him.

SP

Well, he could be very gruff, you know.

(Laughter)

I’m not sure. Saint could be pretty intense. It might have been the fact that, you know, when you are directing camera operators, when you are shooting documentaries, sometimes you can have two styles. One style can be right over your camera person’s shoulder, and be speaking in their left or right ear telling them how to get the shots, or the second style you can have a little distance from them and let them shoot.

Now, Saint could do it both ways. He could be in your ears and he might have been in their ears telling them how to get coverage. He knew these guys a long time, he understood what they wanted and how to get it. I would have to be on the set to see how it worked. When I was on the set with Saint, I thought that as an interviewer he was very intimidating, which is the opposite of my style. Because sometimes you felt like it wasn’t the person being interviewed. It was Saint saying “I’m the interviewer.” He didn’t act like that in this, so I don’t know.

Audience

On the films that you worked together on, how much time would he spend beforehand getting to know either the situation or the people or the community?

SP

Well, when he did The Black and the Green, he knew these people really well. When he started shooting that in New York, he was pretty close to all those people before he shot. And they knew Saint well. They felt very comfortable with him. He was sort of like a fly on the wall. They just trusted him.

It was the same when he did Big City Blues in Chicago, they all knew Saint and they felt comfortable with him. But he was a big presence, six feet, five inches. He would come in the room and just take over the room. He would swallow up the room. But he knew how on the film set to sort of dwarf himself and let the subjects do their thing.

J S-G

Do we know who Icarus Films credits? Either way I think it’s great that either Madeline Anderson or Kathleen Collins cut the film. Do you know who actually cut it? Was it both?

SP

Kathleen cut this one.

J S-G

But on Icarus, they credit …

SP

Might have been the supervisor, then. Anybody who has seen Losing Ground (1982) knows Kathleen was a phenomenal filmmaker in her own right and you can feel her sensitivity there with the editing. The director/editor relationship is complicated. Saint gave you a lot of room.

He gave you the material. He let you edit and then he would come in and he would critique and ask you to make changes. But he never sat over you. None of the films I ever worked with he ever sat over me. So that’s why I enjoyed the experience. I know with Kathleen, he probably didn’t do that because she was a filmmaker herself.{1}

JL

I want to go back for a second to a question about the intimacy. I’m stunned especially in the Mississippi scene at the pastoral walk with that pastor. There’s something that does feel so natural. But we also know that that’s such an intimate conversation between a pastor and a seminary that wouldn’t happen in front of a camera, probably not while wearing a suit.

SP

I sort of challenge that one.

JL

Yeah? With the camera?

SP

Yeah, I shot a lot in Mississippi. And my family is from Mississippi.

JL

So is my family!

(Laughter)

SP

You are asking the question because you know, Mississippi Black folk are real natural.

(Laughter)

SP

They are real natural.

JL

They want to discern a call to preaching in front of a camera, on camera? I don’t know.

SP

They are natural. I grew up in churches like that. These people are natural.

AG

Well, I think that the Mississippi pastor answers your question. He says, “we don’t just do church on Sunday.”

JL

Yeah.

figure 6. LET THE CHURCH SAY AMEN!. Courtesy of Icarus Films.

figure 6. LET THE CHURCH SAY AMEN!. Courtesy of Icarus Films.

AG

It is who we are, every day of the week we doing church. So, I think that’s what I thought about when you guys were talking about this sense of the natural — I think it has something to do with the subject matter, too. If you are a person of faith growing up in Mississippi, then that’s embodied in your blood and DNA, talking about Jesus.

SP

24/7.

AG

That’s why my shirt says “churchy.” I do church all the time. That’s part of the genius of the film. Church is a part of who they are. So I think it’s a fair pushback to say, “yeah, this guy is discerning his call.” But that moment is so intimate because they live and breathe this church experience.

JL

Okay, I will be pushed. That’s all right.

SP

It’s like if you are a musician and that’s what you speak and you live, you don’t feel uptight. It’s the feeling deep inside.

Pegi Vail

Thank you. Any last words before we wrap up?

SP

I’ll say this. When Faye (Ginsburg) asked me to do this, there was no way I would say no. I would never say no to talk about anything, or screen anything, about Saint Clair Bourne, because there’s three people most important to my film career, and Saint is on that list.

****

Acknowledgement

This antiphonal party was made possible by Faye Ginsburg, Pegi Vail, and the Center for Media, Culture, and Religion at New York University, the NYU Department of Cinema Studies, Icarus Films, and Joshua Edwards who transcribed this conversation.

Title Video: Let the Church Say Amen! (Bourne, USA, 1973)

{1} Hayley O’Malley, a doctoral student at the University of Michigan, confirmed by email after this discussion that Kathleen Collins edited Let the Church Say Amen!. See “Cinema Happenings Film ‘Let the Church Say Amen!’,” in Daily Defender (March 19, 1973) p. 11.