Shirley Clarke: But there is a difference between an automobile and a movie.

James Degangi: There isn’t any difference.

—from “Film Unions and the Low-Budget Independent Film Production”

****

I’ve never set foot in the city of Rotterdam, but for most of my adult life there are two things I’ve known about it. The first is that Rotterdam became Rotterdam owing to its position as the gateway, in the mid-nineteenth century, out of the coal mines of Germany’s Ruhr Valley. Later, after the Second World War, it became the gateway into Western Europe for the crude oil that arrived on ships from the Persian Gulf to be refined along Rotterdam’s shores.

The second thing I’ve known about Rotterdam is that it’s home to a film festival. And not just any festival, but a prestigious one, and one at which I seem to have one or two friends excited to premiere their latest films each year. A few years ago, two of those friends were Emily and Cooper. Emily and Cooper were set to travel to Rotterdam to premiere You Are an Amazement (2019, later retitled You Were an Amazement on the Day You Were Born), but first they had to figure out a place to stay. As many working filmmakers already know, there’s often a two-tiered accommodation system at A-list festivals. Feature films in the program tend to earn their makers a free flight and, say, three nights’ hotel stay, but short films tend not to. Cooper and Emily had made a twenty-eight-minute video, well below the airfare and accommodations cutoff. But since they earn salaries as tenured faculty at an American university, they decided they could just pay out of pocket to head to Rotterdam and accompany their work. As a gesture of goodwill, Rotterdam sweetened the deal by offering a few nights’ stay in a hotel, compliments of the festival.

Feeling spent following the transatlantic flight, Cooper and Emily nevertheless decided to make the most of their first evening in the city and attend a festival-sponsored party at a nearby bar. They reached the decision despite the fear that—in their words—it would suck, because they wouldn’t know anyone there. To Emily’s delight, just as soon as they sat down at a table, she looked across the room and recognized a programmer who had recently featured their work at another European festival. It occurred to her how silly it was to think they wouldn’t have anyone to talk to. Their film got into Rotterdam, after all. People would want to talk to them. So she smiled at the programmer and made eye contact. And he looked right past her.

Emily describes what happened next as the feeling of a pendulum swinging inside her head, pulling her sense of self backwards and forwards.

Our video is premiering at Rotterdam. I am somebody. But it’s only a short and it’s in a group screening. I am nobody. This isn’t our first time screening here. I am somebody. But we never win awards. I am nobody. We got a free hotel. Somebody. But it’s not as nice as the one we got last time. Nobody.

She telescoped, in her words—You look through one end of the telescope and you are a giant. And you look through the other and you are tiny—between the sense that they were exceptional artists in a room full of people, and the sense that they were the exceptions to a room full of exceptional people. It was a room of winners and losers; she just couldn’t tell which category best described them.

Excerpt from YOU WERE AN AMAZEMENT ON THE DAY YOU WERE BORN (Emily Vey Duke and Cooper Battersby, 2019). Courtesy of the artists.

We know that nonfiction films are more, and less, than panes of glass letting the light of the world shine undistorted onto our screens. But Emily and Cooper’s description of their time telescoping on the festival circuit, equally intoxicating and disorienting, strikes me as a faithful depiction of the documentary world I inhabit. It describes what the world so often feels like for nonfiction media makers of one kind or another—which in the age of social media is almost everyone, for whom the distances between work and labor, labor and leisure, self-actualization and collective belonging, and self-worth and alienation are always collapsing.

What I like about Emily’s use of telescope as a verb is that it frames perspective as a choice as much as a sum, and as a sensation that complicates as much as it clarifies observation. It describes a filmmaker-centered way of seeing that’s determined as much by how she wishes to be sized in relation to the world as by how she feels sized in relation to it. It also emphasizes the tendency of writing about independent cinema (scholarship, criticism, promotional copy) to grant filmmakers and their visions an outsized relationship to the institutional landscapes they traverse. Vision is the watchword of independent cinema. Looking through North American festival write-ups from the first three months of 2022, I’ve come across many adjectives linked to the vision of filmmakers: artistic, creative, unsparing, risky, shared. The adjective form visionary is equally abundant. I wonder: Does the emphasis on filmmakers’ visions in the writing about independent film produce a trick of perspective, magnifying the power that individual filmmakers hold beyond what the field actually affords?

I tell Emily and Cooper that their story reminds me of Russell Edson’s prose poem about a tragicomic encounter of two parents who misrecognize their own son when he comes too close—No, no, our son lives in the distance, says the little husband.{1} The poem is called “The Optical Prodigal.” When Edson talked about it he’d clarify that it was not supposed to be some morality tale about returning home chastened or coming around to another perspective.{2} Really, it was just about relationships being messy. They don’t come with proper focal lengths. Cooper and Emily agree; looking through one end of the telescope doesn’t bring any particular balance to the view from the other side. The only thing it brings with it for certain is vertigo, a general sense of feeling off-balance.

This volume is an attempt to honor the contradictory perspective. Independent filmmakers encounter festivals as places of work and leisure, exploitation and advancement, inclusion and exclusion, scarcity and abundance. At least, that is, when filmmakers encounter festivals at all. If getting in can still feel like losing, a rejection might make one question their existence altogether.

MAYBE IT WILL LEAD TO SOMETHING (2018). Video by Phil Solomon, text by Jason Fox.

Filmmakers also experience festivals as places from which to gauge the value of their art—even when and despite all they know of the mundane, compromised, and idiosyncratic considerations that actually go into making festival program selections. Telescoping describes the challenges that underwrite our efforts to gauge the value and effects of transnational relationships of independents—that is, independent festivals and the independent filmmakers who flesh out their programs—as they have grown and organized the nonfiction media horizon over the past three decades. Too sprawling, diverse, and contradictory in size and aim, organization and audiences to generalize in any useful way, festivals in this issue are shared spaces—sometimes foregrounded and at others receding to the horizon—into which vital questions around compensation, the role of criticism, individual and collective production models, radical politics and aesthetics, and global supply chains bleed.

The question of value and values can be especially dizzying for people who are active in the worlds and activities they also critically observe. Anything, including artistic vision, can be made into a commodity. But does it necessarily follow that, from a social and economic perspective, we should value artists’ films as if they were no different than oil? I hope not; or maybe some part of me wishes that renewable energy were the better analogy. But that question points to another one about the exceptional and contradictory status of creative labor, one that has returned in various guises throughout the last century. The question resurfaces here in the context of globalized networks of independent cinema: Is the work that festivals do, or can do, uniquely expressive of the logic of contemporary capital, or is it exceptional to this logic? If the latter, how so? What alternative ways of organizing resources and energies can festivals help us picture?

****

“It astounds me,” filmmaker Shirley Clarke gasped. She was referring to the union situation. “There is a general feeling among independent filmmakers that the unions stand between them and their art,” added film director Lew Clyde Stoumen. Clarke and Stoumen, alongside Willard Van Dyke and brothers Jonas and Adolfas Mekas, all filmmakers affiliated with the burgeoning New American Cinema (NAC) movement in early-1960s New York City, formulated their concern about alternative organizations in part as a union question. They then took that question straight to film-local head James Degangi. {Article 02} As Clarke and Jonas Mekas saw it, an artificial border had been drawn across the field of creative activity, separating the artistic labor of poets and painters from the waged labor of filmmaking. To them, being an artist meant being free to be worthless. It meant setting one’s own terms by which to be a visionary; it meant reimagining the logics that organize the world. And that’s what Clarke and Mekas wanted for their own craft. But filmmakers were still mostly organized by assembly lines and union rules and mass-production models. Film was industrial, and the NAC resented being subjected to the economic logic of an industrial world in which monetary value was attached to everything, whether it was wages for work or cash for commodities.

Contingency is the term cinema scholar Josh Guilford uses to conjure the contrarian spirit with which the burgeoning New American Cinema Group resisted such a world by translating their desires into new forms of creative organization. Guilford writes that the “artists of the NAC associated the late-modern era with an overwhelming excess of reification, often framing the surrounding world as a static, artificial gridwork or machine, and railing against the deadness of everything from commercial cinema to civilization more generally.”{3} The establishment, which referred equally to corporate and communistic forms of mid-century organization, was too rational, too lacking in spontaneity, and too hierarchical. And so they cultivated a new crop of ad hoc organizations in New York, including the Film-Makers’ Coop, Anthology Film Archives, the journal Film Culture, and the New York Film Festival, all of which were intended to sustain a new culture of independent artist cinema.{4}

In a 1969 correspondence between Bruce Conner and Jonas Mekas regarding Film-Makers' Coop screening fees, published in CANYON CINEMANEWS, Mekas writes: "I have been hearing from Bruce for three years now. He keeps kicking me whenever he feels so, just for kicks. Being a farmer, I'm very patient. And I have said on a number of occasions, that an artist is right even when he is wrong."

In a 1969 correspondence between Bruce Conner and Jonas Mekas regarding Film-Makers' Coop screening fees, published in CANYON CINEMANEWS, Mekas writes: "I have been hearing from Bruce for three years now. He keeps kicking me whenever he feels so, just for kicks. Being a farmer, I'm very patient. And I have said on a number of occasions, that an artist is right even when he is wrong."

Being a farmer, I’m very patient.{5} Jonas Mekas wrote that line to Bruce Conner in a semipublic epistolary feud with the San Francisco–based artist over how funds coming into the Film-Makers’ Coop were, or weren’t, being allocated back to filmmakers. Mekas’s preferred metaphor for his creative toil turned on the image of a farmer, alone in the field. It’s kind of funny, since his intellectual activities thrived—could only thrive—within the gridwork of New York City. Similarly, Shirley Clarke evoked the lowly lumberjack to express her own concerns. In 1961, she lamented, existing union labor rules dictated that she’d need a crew of six technicians—a camera operator, an assistant, two electricians, and two grips—to record a single shot of a tree standing in a forest, making truly independent cinema impossible in number and spirit. The farmer and lumberjack are deliberate images of a solitary laboring body. They are evocative of a simple and gentle self-sufficiency, of an eternal common sense that transcended their mid-century urban setting, leading the Film Culture roundtable to conclude on a note of cautious optimism. This new breed of laborers gathered around the table—Adolfas Mekas: They are not producers, not cameramen, not teamsters . . . they are filmmakers—decided they would employ their folksy common sense as leverage while negotiating with the film unions, which they hoped would make allowances for independent filmmakers who wished to work in less restricted ways.

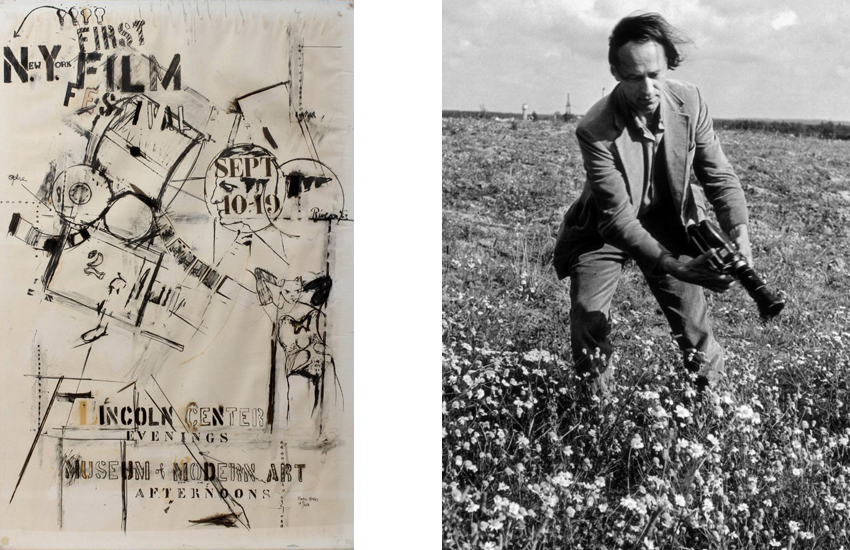

Two visions of the camera operator. (L) Poster created by painter Larry Rivers for the inaugural 1963 New York Film Festival. (R) Jonas Mekas filming in his hometown of Semeniškiai, Lithuania, 1971.

Two visions of the camera operator. (L) Poster created by painter Larry Rivers for the inaugural 1963 New York Film Festival. (R) Jonas Mekas filming in his hometown of Semeniškiai, Lithuania, 1971.

Sixty-one years after the tape recorder was switched off, and the NAC filmmakers’ on-the-record conversation came to a close, whole swaths of the filmmaking industry have left the factory, so to speak, abandoning (or having been abandoned by) the prospect of jobs as workers in order to become independents. These days, our creative labor is often supported by grants, or by working jobs that afford us the ability to do our preferred work for free, or maybe it’s supported by personal family funds (as was the case with Clarke). For those who can’t rely upon the latter, it’s a trying and often tiring system. And so I encounter the roundtable discussion with a subtle taste of sourness in my mouth. I’m inclined to sneer, dismissively, at their pursuit of non-union production models as I fantasize about the kind of security the union rules they malign might provide for creative workers today. At the same time, I sympathize with the NAC filmmakers’ frustrations and their modest desire to make work on their own terms, with small budgets, and in accordance with their own visions. And besides, they weren’t wrong: the editor’s and cameraperson’s unions were closed clubs in the early 60s. But neither of these reactions feels wholly satisfying. Historical judgments, like nostalgia, come too easily. What’s more useful, I think, is to reflect on what today’s independents, myself included, can find wedged between these two perspectives. What can be reconciled between these contradictory judgments, between the urban avant-garde and agrarian images of work Mekas and Clarke evoke, between the desire for independence and the need for interdependence, and between the two moments of 1961 and 2022?

To them, being an artist meant being free to be worthless.

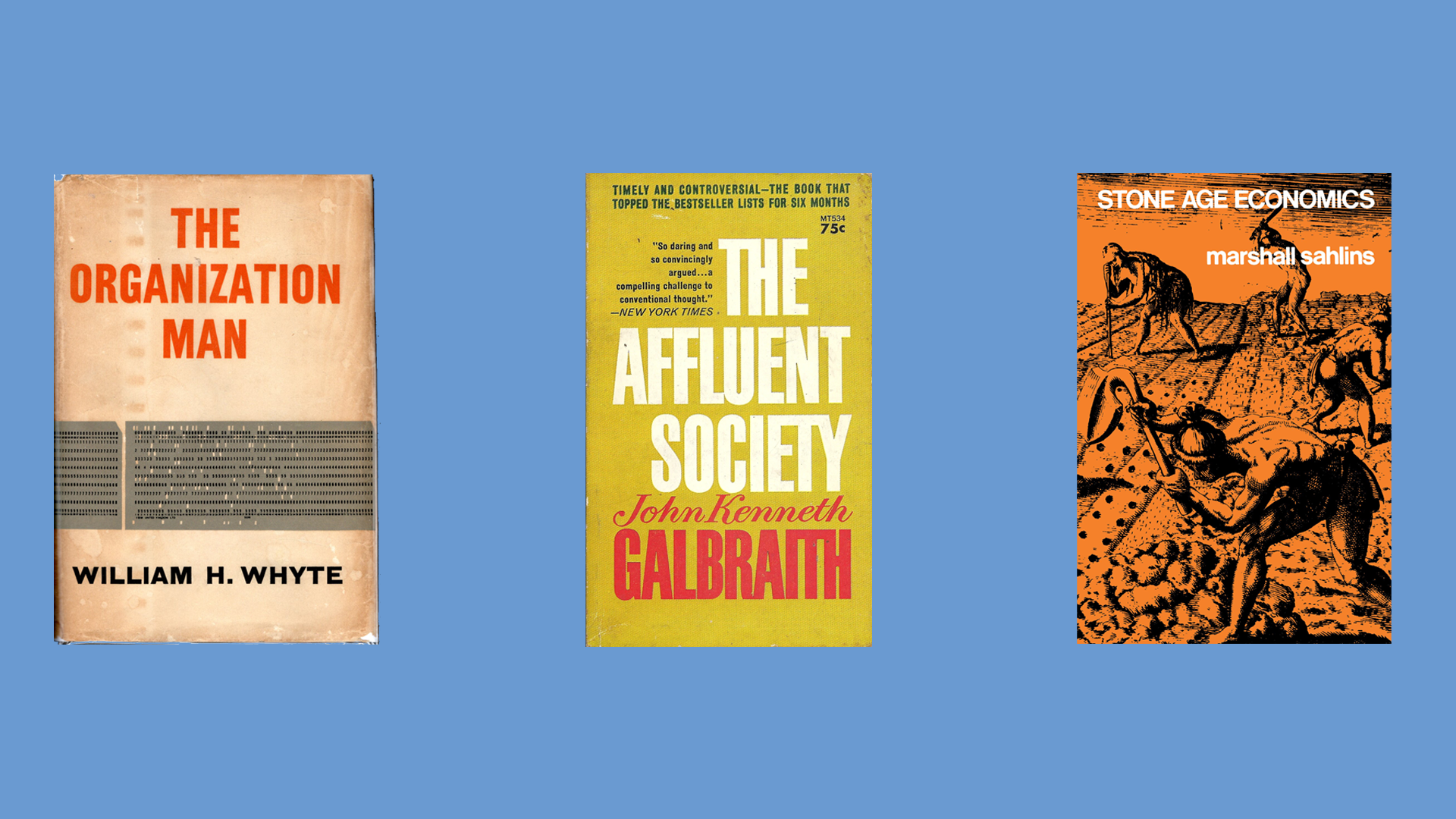

For starters, I wonder if independent, as a badge of self-identification, signals a desire to see one’s work as a corrective to the current state of things rather than as an expression of the way things actually are. Jonas Mekas: “The entire landscape of human thought, as it is accepted publicly in the Western world, has to be turned over.”{6} He was interested in the modes of creative work that might be possible if the need, desire, or demand for gainful employment disappeared, and he was committed to the forms of cinema culture that could flourish if consumption wasn’t the operative metaphor describing spectatorship. And so his figures of speech turned to the fields and forests, as a space not for escape but for restoration. He mythologized a way of making and sharing that reinvigorated life instead of reducing it to commodities, and that sustained artists rather than merely compensating them.{7} It occurs to me that his creative ideal resonates with what John Kenneth Galbraith had described just a few years earlier as the emerging, mid-century affluent society.{8} The affluent society, according to Galbraith, referred to a growing comfort class who recognized that pay isn’t synonymous with fulfillment and who desired to work for prestige rather than labor for money. Mekas’s farmer also resonates with how renowned anthropologist Marshall Sahlins described early hunter-gatherers as the “original affluent society” just a few years after the Film Culture roundtable took place.{9} Lots of people, it seems, were trying to imagine what value looked like when the boundaries between art, work, and daily life were erased.

The theoretically infinite and essentially democratic vision to be made possible by this new creative culture was perhaps best articulated by Mekas’s contemporary and occasional colleague, Stan Brakhage, who asked: How many colors are there in a field of grass to the crawling baby unaware of “Green”?{10} He too, it seems, felt most able to imagine a world without boundaries by way of a fertile field. Maybe he wrote this line as he was looking out his own window, imagining the fields surrounding the home where he would soon live, off the grid, literally and figuratively, for much of his adult life with his family in the foothills of Colorado’s Rocky Mountains. Stan was the first film teacher I ever had, but he hadn’t been on my mind much until I came across the artist Amanda Williams’s Color(ed) Theory Suite (2014–16) a decade later. In Williams’s project, the artist painted houses on Chicago’s South Side which had been deemed worthless, at least from a real estate investment perspective, and marked by the city for demolition. The paint colors she chose were borrowed from products like Crown Royal (purple) and Newport 100 (turquoise) that had been heavily marketed to Black people in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. The colors were precisely defined, the antithesis of Stan’s infinitely chromatic field. Her colors forged a social bond between those who grew up among those products, and they were also a form of capture. Though the houses were transformed by Williams and teams of volunteers from bad real estate into art, they couldn’t escape their lack of value as commodities. And they were bulldozed by the city of Chicago shortly after.

COLOR(ED) THEORY SUITE (Amanda Williams, 2014–16). Images courtesy of the artist’s website. Audio recording courtesy of MoMA.

I first met Stan when I was still a teenager and he was in the final two years of his battle with the bladder cancer that eventually killed him. For those, like me, who were attracted to the Romantic mythos that followed him wherever he went, there was an impossible-to-miss, cruel poetry radiating from his body. His illness, it was thought, was the result of his inhaling carcinogenic pigments contained in the very ink that gave color to the hand-painted 16mm film strips he labored over for countless hours of his adult life. You could call it an occupational hazard of his labor, or you could say he was a real artist consumed by his art, escaping the life of a commodity producer so that he might produce something real. Either way, these days I’m struck by a more prosaic irony. Having committed himself to a life in the mountains free of social obligation, his final year was spent in Victoria, British Columbia, where he moved with his wife in 2002 so he could access Canada’s socialized healthcare system. It is a system that afforded him the opportunity to die with as little pain and as much dignity as possible.

What hasn’t changed in sixty years is that everyone still desires and deserves dignity. And our cultural struggles—in cities and cinemas, at festivals or in the fields—are always real insofar as they focus on how our labor creates meaning and value. Lew Clyde Stoumen, at the Film Culture roundtable: As the artistic creator of the film, I want to be able to determine the conditions of my production, which is more than fair to ask. It is fair, but the metaphors we use to frame the question have a great deal of influence on how we imagine self-determination. Honoring one’s own vision is a phrase we independents often use to talk about dignity. But as even Brakhage knew, vision is just a metaphor. I wonder if it conceals as much as it reveals, even as it encapsulates the contradictions of the artist-film era. Vision can be free to wander, free of obligation, and can cost nothing. It’s personal, it resists commodification, and it can lend itself to projects of radical imagination. Vision can be withdrawn or noncommittal. And it can merely, like another phrase frequently invoked in festival programming, survey the field. Vision is artistically valuable because it’s financially worthless, we might tell ourselves, even though this is not really true.

I don’t have much desire for limitless possibilities these days; instead I find myself seeking different possibilities. The establishment may still be bad, as the New American Cinema Group suspected, but liberating visions alone won’t do much to change that. What independent organization looks like, has been imagined to look like, and could look like still, is one of the concerns that runs throughout this issue of World Records. It’s telling that as this issue goes to print, one of the most prominent documentary organizations in the US supporting independent filmmakers, the International Documentary Association, is actively organizing to form a workplace union (though what it’s telling of remains to be seen). Whatever else precipitated their efforts, I hope, and suspect, that the employees already knew what labor organizer Jane McAlevey discovered. Most people, she writes, assume that “material gain is the primary concern of unions, missing that workplace fights are most importantly about one of the deepest of human emotional needs: dignity.”{11}

****

“Start from where you are standing,” Eli Horwatt writes.{Article 07} He’s referring to the organizing strategy taken up by a network of filmmakers who are increasing pressure on festivals to offer screening fees. It’s a strategy I’m also taking up here. There are other departure points for this issue well beyond the concerns of the New American Cinema Group, but I want to start with the histories embedded in Lower Manhattan because that’s where World Records is standing. It’s where the journal has an exciting new home with the Center for Media, Culture, and History at New York University.

At its most meaningful, the term experimental—maligned and celebrated in equal measure—qualifies a pursuit of cinema that stitches together the contradictory conditions in which we make work into a stream of life. What is or can be socially transformative about cinema, as contributors Genevieve Yue, Juliano Gomes, and Stefan Tarnowski remind us, always requires a link between onscreen and offscreen practices. How these relationships become transformative is the experiment, because they can seldom be determined in advance. “A film is always an entry point into a set of sociopolitical conditions,” Yue writes, not an escape from them. {Article 03}

The same is true of festivals. Abundance and scarcity and desire and frustration shape those conditions, and unevenly so, for many of us independents. We can ask questions about what conditions are valuable for independent filmmakers, just as we can ask what is valuable, and why, for independent cinema institutions. But those questions depend on others: What’s valuable for independents in general, and what possible work can organize it? This issue attempts to think about these questions together.

{1} Russell Edson, “The Optical Prodigal,” in Edson’s Mentality (Chicago: OINK! Press, 1977), 17.

{2} See Michel Delville, “Strange Tales and Bitter Emergencies: A Few Notes on the Prose Poem,” in An Exaltation of Forms: Contemporary Poets Celebrate the Diversity of Their Art, ed. Annie Finch and Kathrine Varnes (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002), 263.

{3} Josh Guilford, “Disorganized Organization: Signs of Life in the Film-Makers’ Cooperative’s Paper Archive,” World Records Journal 4 (2020): 173.

{4} They is, admittedly, a slippery word. Amos Vogel, who would take a leading role in the founding of the New York Film Festival, and Jonas Mekas would have likely shuddered at the thought of being bound together by the same they.

{5} Quoted in Johanna Gosse, “How to Make a Scene: Ray Johnson and Jonas Mekas as Underground Publicists” (Online Symposium: Jonas Mekas and the New York Avant-Garde, February 12, 2022, virtual). The Mekas quotation is taken from a letter dated May 20, 1969, and published in “Exchanges,” Canyon Cinemanews 69, no. 4 (1969).

{6} Jonas Mekas, “Notes on the New American Cinema,” Film Culture 24 (Spring 1962): 14.

{7} See David E. James, Allegories of Cinema: American Film in the Sixties (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 103.

{8} John Kenneth Galbraith, The Affluent Society (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1958).

{9} Marshall Sahlins, “Notes on the Original Affluent Society,” in Man the Hunter, ed. Richard B. Lee and Irven DeVore (New York: Aldine Publishing Company, 1968), 85–89. Sahlins first presented the paper in 1966 at the University of Chicago as a part of the Man the Hunter symposium organized by Lee and DeVore. The gendered implications of this outlook are less than subtle, as Jane Collier and Michelle Rosaldo, among others, have pointed out. See Jane F. Collier and Michelle Z. Rosaldo, “Politics and Gender in Simple Societies,” in Sexual Meanings: The Cultural Construction of Gender, ed. Sherry B. Ortner and Harriet Whitehead (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 275–329.

{10} Stan Brakhage, “Metaphors on Vision,” in Essential Brakhage: Selected Writings on Filmmaking (New York: McPherson and Company, 2001), 12.

{11} Jane McAlevey, No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 1.