Who Are Film Festivals For?

Eli Horwatt

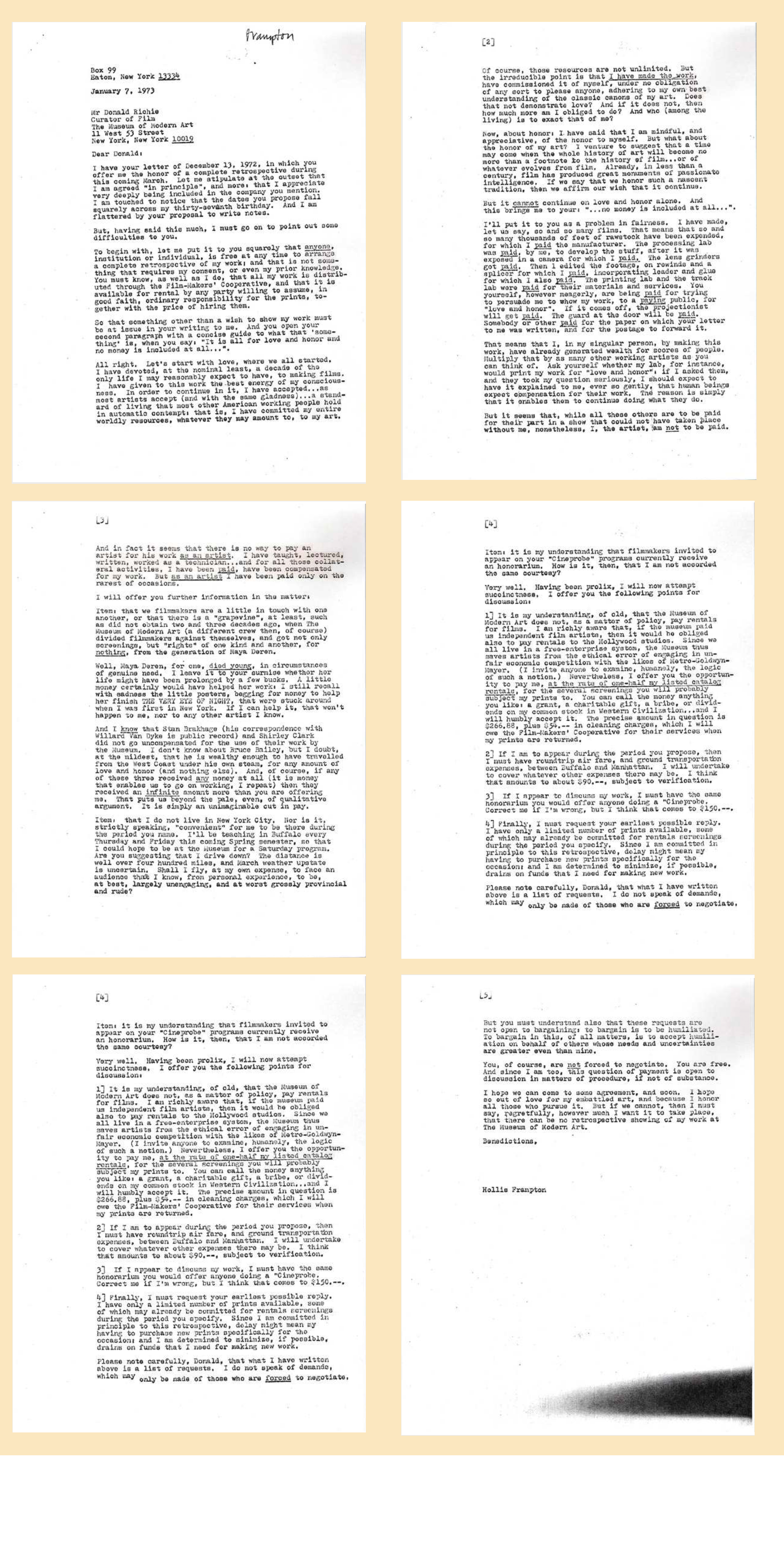

So that something other than a wish to show my work must be at issue in your writing to me. And you open your second paragraph with a concise guide to what that “something” is when you say: “It is all for love and honor and no money is included at all . . .”

—Hollis Frampton, letter to Donald Richie, January 7, 1973

****

The email reads: “You have been accepted!” As any working independent filmmaker knows, being accepted is the exception. The scarcity of space for films in a festival guarantees a significant number of rejections, underscoring the supply-and-demand logic these organizations run on. This has naturalized an asymmetrical relationship of power which, as stated in Frampton’s letter above, allows festivals to solicit a filmmaker’s participation for “love and honor,” rather than for any tangible form of remuneration. The economic model underwriting most festivals works like market futures, as the unspoken promise to a filmmaker rests in the hopes of receiving the prestige, press, or distribution that festival exposure might offer. But any money trading hands at this event will likely not touch the person providing the film.

It begs the question: Who are film festivals for?

From a labor perspective, the biggest contributors in revenue and prestige to film festivals are filmmakers themselves. Their product rationalizes the advertising, sponsorship, grants, and donations that keep festivals running. Filmmaker participation, through promotional events and conversation with audiences (itself a form of immaterial labor), generates cachet to enrich the public perception of a film festival. And yet, in this moment marked by an ostensible glut of films and scarcity of attention, festivals and their disparate arms have been the greatest beneficiaries of the surplus produced by these event-based screenings.{1} Revenues, alongside prestige, have ballooned in the past twenty years at key documentary film festivals and sidebars, but there have been few attempts at sharing power with filmmakers in the form of remuneration.{2}

This essay investigates what might be done about this imbalance. In the conversations that color this text, implementable proposals and strategies emerge that consider the financial realities many filmmakers face after the parties and screenings end. By avoiding fatalistic conclusions that either accept defeat or demand non-participation, the filmmakers and programmers I spoke with offer ways to redress exploitative economic practices that underwrite film exhibition, even as these same individuals remain active in the field. Along the way, the interviewees also provide a lens through which to better see how festivals operate.

Few major film festivals across North America and Europe offer direct compensation to filmmakers. Instead, exchange value for filmmakers appears through various unquantifiable forms of promotional value and industry access. Festivals trade on filmmakers’ hopes of a distribution deal, publicity, and, occasionally, competition-award earnings. But a substantial number of the films that screen do not receive distribution and aren’t placed in competitions. From a filmmaker’s perspective, it might follow that if resources are unavoidably scarce on the front end, then filmmakers’ compensation should appear in significant post-festival futures.

Or maybe not. After all, what’s wrong with approaching festivals as ends in and of themselves, spaces in which filmmakers trade not for money but for the pleasure of sharing work with others? Nothing—except that if this is to be the case, festivals should answer first to filmmakers, instead of being indebted to boards, donors, and advertisers. This leads to another question: Whose investments are recuperated?

Lewis Hyde's international best seller THE GIFT (1983) distinguishes between the kind of work that is done by the hour, and the kinds of poetic labor that are done for a community of people, as a gift, in which the reward isn't money but social transformation.

Lewis Hyde's international best seller THE GIFT (1983) distinguishes between the kind of work that is done by the hour, and the kinds of poetic labor that are done for a community of people, as a gift, in which the reward isn't money but social transformation.

For filmmakers who have participated in and rely upon the festival system, nothing I have said so far will come as a surprise. But what comes next is still an open question. What happens when we realize those post-festival futures, in many cases, aren’t to come? Could one imagine a scenario in which festivals reorient to address the economic realities of the filmmakers they celebrate? It’s a question that I posed to filmmakers and programmers who aren’t willing to accept diminishing returns. I proceed by reiterating the questions posed by documentary director and programmer Samara Grace Chadwick, who asks,

Who’s it benefiting—what does the film festival do and what and who is it accountable to? In the public sphere and on [festival] websites, there is much said about filmmaker-friendliness, but ultimately festivals are accountable not to their filmmakers but rather to their boards, donors, advertisers—and more and more to major players like Netflix.{3}

As most mission statements, press releases, and grant applications from documentary film festivals will tell you, a festival’s foremost goal is to support filmmakers.{4} But few festivals define support as fair remuneration. If festivals can’t afford to pay filmmakers, it may be argued that those festivals don’t have the adequate funding to continue. The problem doesn’t stop with screening fees, but it’s one place to start.

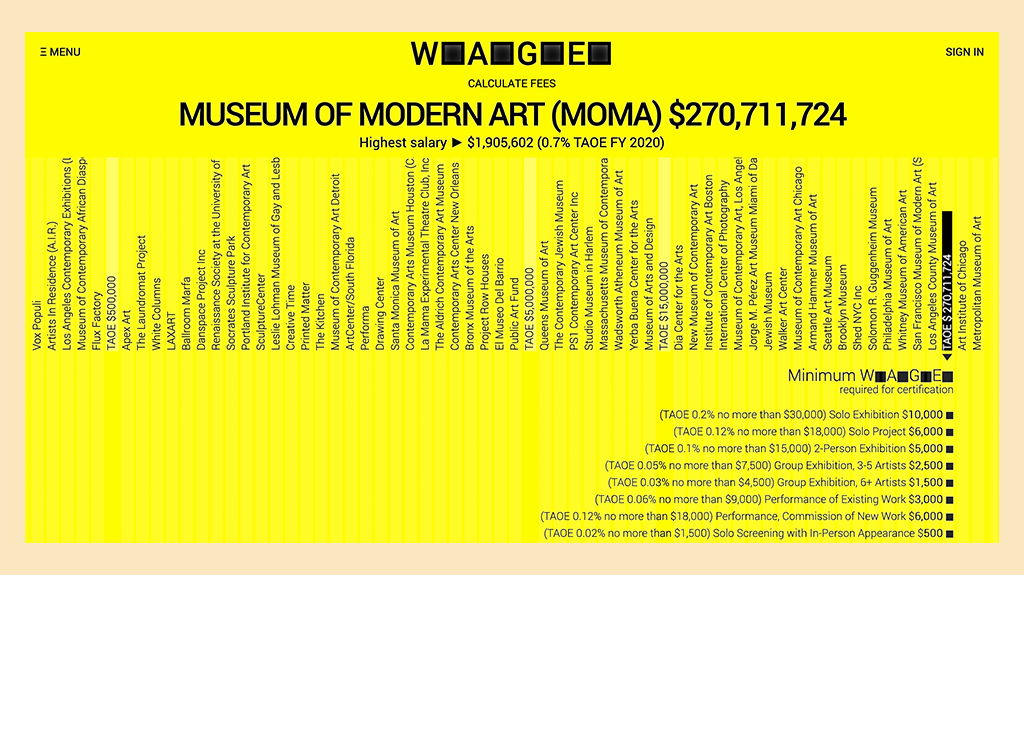

Responding to poor to nonexistent remuneration policies by cultural organizations across the US, the activist organization Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.) formed in 2008. Their goal was to address exploitative conditions by establishing equitable pay scales between artists and cultural institutions. By creating an infrastructure of data collection, open letters to cultural organizations, and public forums, W.A.G.E. now offers certification to nonprofit arts organizations that voluntarily pay artist fees and meet minimum payment standards.{5} Documentary filmmakers are currently implementing many of these initiatives in the festival community. As W.A.G.E.’s efforts make clear, there’s nothing unique about film festivals’ scarce payment practices, though festivals may be particularly severe offenders in the US sphere of cultural exhibition.

What is the role of festival gatekeepers—a term that programmers tend to abhor—in these practices? Programmers are more often aligned, economically and socially, with the filmmakers they exhibit rather than with the administrations they work for. And yet they are placed precariously, and perhaps strategically, between institutional policy and the economic interests of the filmmakers they work with. Such a position thrusts programming work into a kind of parasitic economic activity, wherever this work relies on the unpaid labor of filmmakers to function.

But it needn’t be that way. It’s true that financial decisions may be the province of executive directors, but it’s also true that most festival programmers—even some of the most visible—aren’t typically well paid. It is yet another job full of long hours and low pay, and it is often restricted to seasonal employment. Acknowledging this reality, many of those I interviewed called for a more collaborative solidarity between programmers and filmmakers, in order to shift policies toward fair remuneration. Many also admitted that actively pressuring festival administrators is a nerve-racking proposition.

****

The Time Event

Film festivals capitalize on the time-event nature of festival screenings. Or so argues programmer Mark Peranson, who distinguishes festival screenings from more general theatrical screenings at independent cinemas. The time-event quality of festivals is backed by an apparatus of marketing and press coverage that often surpasses the kind of attention and attendance a film could hope to garner during a week-long run at a theater. Festival screenings, which may include celebrity, documentary-subject, or filmmaker attendance, generate a strong allure and emotional bond with audiences. Peranson’s point is that festivals’ ability to draw large audiences can cannibalize the demand in a region for a later theatrical run.

In other words, festival screenings can generate a host of positive promotional effects, but they can also cut into a filmmaker’s bottom line. For small-to-medium-budget documentaries, three large festival screenings in a city may threaten the viability of getting the week- or weeks-long run needed in a major metropolis to recuperate a film’s expenses. Peranson writes, “If anything, one can say that in their local contexts, international film festivals are too successful, as the real spectre haunting the film world is declining attendances at so-called arthouse theatres year round, especially in screening facilities that are being built and run by film festivals.”{6}

Sean Farnel, author of “Towards a Filmmaker’s Bill of Rights for Festivals,” elaborates on the problem of the time event.{7} As the director of programming for Hot Docs from 2005 to 2011, Farnel led the organization through a veritable golden age of programming innovation; he now works with independent filmmakers as a consulting producer. His simple proposition is: What if film festivals were turned into direct revenue models for filmmakers? How can the festival be a part of, rather than merely a launching pad for, financial compensation?

Farnel has come to understand that screening fees would likely only deliver a fraction of a film’s total budget back to the filmmaker. Revenue models should be pursued beyond screening fees, he argues, invoking the need for direct revenue sharing in which portions of the ticket sales at the festival go back to the filmmakers. Revenue sharing may actually bolster a filmmaker’s incentive to promote and advertise their film screenings, which may translate to higher ticket sales and revenues for a screening. Far from threatening the viability of festivals, payment to filmmakers is, in Farnel’s view, not only a moral imperative but a necessary policy shift to guarantee the continued vitality of independent cinema at large.

But it’s not just the back end of exhibition revenue sharing that’s a problem. The majority of festivals also impose a regressive front-end tax in the form of submission fees. Farnel estimates, for example, that the Sundance Film Festival makes around US$1 million from submission fees each year, despite accepting only 2 to 4 percent of unsolicited films.{8} The overwhelming majority of work that is screened is either solicited by the festival or entered through back channels, particularly when a production has a press or sales agent, or the filmmaker has a personal relationship with programmers. Such an economic model underscores the enormity of labor exploitation at the heart of many festivals, which harvest significant portions of their operating budgets from filmmakers who have no chance of getting into festival lineups. Farnel suggests that paying submission fees actually reduces a filmmaker’s chance of getting into many festivals. This is because solicited films, for which there is no submission fee, come with a built-in interest to the festival, and are usually viewed by programmers in the upper echelons of the organization. Samara Grace Chadwick argues festivals are effectively “scraping their money from the poor” when they prey on the hopes of an underclass of filmmakers. Experimental filmmaker Nazlı Dinçel puts it in starker terms: “Submission money funds festivals, which means that rejection funds festivals.”

Still, as Maori Karmael Holmes, artistic director of the BlackStar Film Festival, points out, submission fees are necessary to protect smaller festivals from being bombarded by work with little chance of entering the festival lineup. But this also reflects the priorities of BlackStar, which culls 70 percent of its films from paid and unsolicited submissions—in stark contrast to larger festivals. “I’d love to get rid of submission fees,” Holmes says, “but right now they keep us from having wack submissions—otherwise we’d be overrun with submissions that are unnecessary. I wish we could offer the festival for free, but in terms of paying for participation, I’m thinking of it as a promotional activity—a launching pad for other screening opportunities,” many of which Holmes herself will go on to organize. Because BlackStar is a smaller festival, focused on “Black, Brown and Indigenous artists working outside of the confines of genre,” its values and financial capabilities reflect very different priorities from those of large festivals that focus more exclusively on industry markets.{9} Mads B. Mikkelsen, artistic director of CPH:DOX, echoes Holmes’s sentiment when he points to distributors’ habit of submitting large packages of films, throwing everything they’ve got against the wall just to see what sticks. In this context, submission fees may provide a filter through which smaller festivals can protect their staff resources.

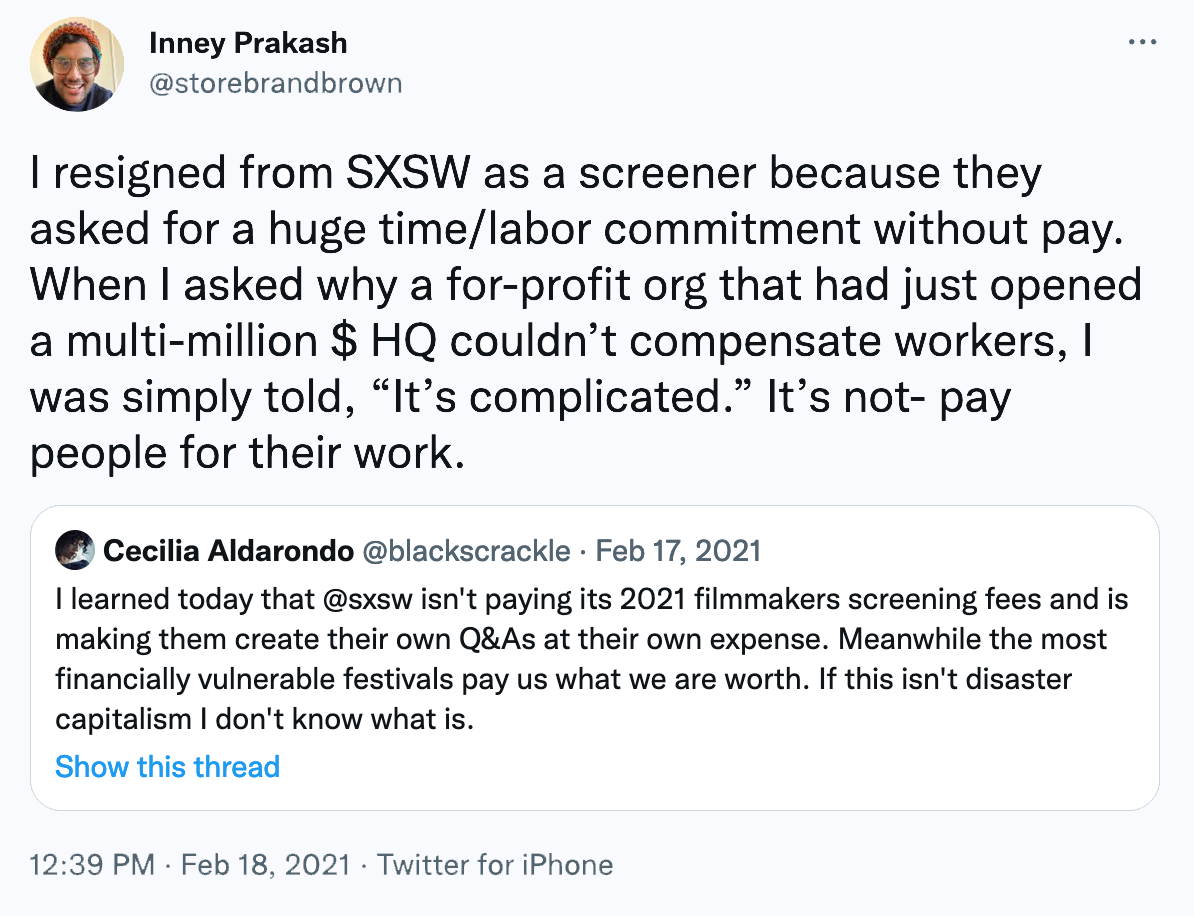

But submission fees do not always subsidize the people who evaluate the films.{10} In a recent Twitter post, SXSW screener Inney Prakash writes, “I resigned from SXSW as a screener because they asked for a huge time/labor commitment without pay. When I asked why a for-profit org that had just opened a multi-million $ HQ couldn’t compensate workers, I was simply told, ‘It’s complicated.’ It’s not—pay people for their work.”{11} On this level, we frequently see festivals milking both sides of the cash cow, charging screening fees and not paying their screeners whose free labor is obtained through promises of work experience and future promotions. Prakash’s tweet was in fact a response to documentary filmmaker Cecilia Aldarondo’s own report on SXSW: “I learned today that @sxsw isn’t paying its 2021 filmmakers screening fees and is making them create their own Q&As at their own expense. Meanwhile the most financially vulnerable festivals pay us what we are worth. If this isn’t disaster capitalism I don’t know what is.”{12}

Weighing the odds of acceptance against the tally of submission fees can be daunting. This is particularly true when, as Farnel argues, festivals that do provide a full-scale experience for the filmmaker (which may include some variation of travel, accommodation, dining, and drinking) are essentially paying out of their marketing budgets, investing in filmmakers as brand ambassadors for the festival. What are presented as filmmaker perks are in fact one more facet of the trickle-down economic model that permeates the psychology of festivals. More precisely, these perks are part of what Farnel describes as an apparatus for producing desire in the filmmaker to exhibit at a festival, to feel honored to do so, and thus indebted to the festival, instead of the other way around. Some festivals even circumvent grant-mandated obligations to pay screening fees by fudging costs associated with travel and accommodation, and listing them as filmmaker remuneration.{13}

In turn, filmmakers often pay substantial sums to attend festivals—initially through submission fees—but once invited, they usually have a maximum of one-third of their costs subsidized by the festival itself. Farnel says, “Our payment is in futures, the compensation in dinners, drinks, hotel, flying, and future screenings. But can you pay your landlord? How do you quantify that exposure?” Ultimately, filmmakers give up money to get invited to the party. This is made all the more caustic in our current and long-standing moment of economic insecurity; as Farnel says, “Filmmakers I know are getting evicted, sleeping on couches, losing jobs, and are more precarious than ever.”

A host of other costs plague filmmakers, especially those who work with material prints. To cite one incomprehensible scenario, in 2019 the Melbourne International Film Festival offered to ship a print from experimental filmmaker Nazlı Dinçel at a cost of US$400, but had no means to pay a €60 rental fee to her distributor, Light Cone, in Paris. Dinçel was publicly outspoken about withdrawing her film Between Relating and Use (2018) from the festival when they refused to rent the film. Even after printing the catalog with the film listed inside it, the festival opted not to show Dinçel’s film rather than to pay for the rental.

Excerpt from BETWEEN RELATING AND USE (Nazlı Dinçel, 2018). Courtesy of Light Cone.

It may be possible that some festivals’ policies and print traffic departments have no means of paying for a film rental—the very idea is outside of some organizations’ nomenclature. Or perhaps there’s another issue at play: that festivals would rather pay more money in shipping than pay rental fees and risk setting a budget and policy precedent. This underscores the much more precarious situation faced by experimental filmmakers, whose exhibition practices have not historically aligned with the promotional logic of the festival, which purports to offer a pathway to distribution, a luxury seldom enjoyed by experimental films. Rental fees can become integral to a filmmaker’s solvency when they show dozens of times per year.

****

Start From Where You Are Standing

A small group of filmmakers, including Aaron Zeghers, Nazlı Dinçel, and Scott Fitzpatrick, always let audiences know during Q&As whether or not they have been paid to screen their work. Zeghers explains: “A group of us said anytime we do a Q&A we mention whether we’re paid or not, and we either thank the festival or encourage the festival to pay artist fees. It’s about education not only of other filmmakers but also of audiences—because they never know; they assume that some of their ticket is going to filmmakers.” As Fitzpatrick explains,

If you’re doing a Q&A and you’re talking publicly about your work, you should acknowledge the economics of it, whether you’re being paid or not. If you’re at a festival that’s doing great work and they’re paying for you, you should let everybody know and shout it out. More transparency around the economics surrounding these exchanges makes a world of difference.

The Q&A tactic effectively tethers filmmakers’ fee struggles to festivals’ desires to have filmmakers accompany their work. While confrontational in tone, Zeghers and Fitzpatrick both speak to the need to work with, rather than against, festivals to effectively create change. Zeghers says,

It’s important to strike a tone that isn’t “we’re gonna burn you to the ground for this” (because there’s way too much of that in the arts and culture scene), but that is “we want to let you know—that the artists aren’t being paid for the screening today”; and often what I encourage people to do is not to slam the festival but to thank the artists who are donating their work to the festival for free.

The gains made around screening fees have convinced the artists that collaborative efforts are essential. Direct attacks on festivals have led to distrust and a further entrenchment of attitudes. The process only works when festivals are invited, collaboratively with filmmakers, to attend to fair pay. Zeghers explains: “We expect a lot from our arts administrators . . . in trying to encourage a little bit more collaboration between those parties and not just seeing each other as evil festival managers and righteous filmmakers. And specifically trying to encourage more solidarity among programmers and filmmakers.” Zeghers suggests that unleashing a torrent of public anger against an institution hasn’t been an effective way forward. Because these organizations are so large, with many moving parts, creating any change within them from the outside requires tact. “Often,” he says, “the institutional reaction to people saying, ‘hey, you should be paying artist fees,’ is to recoil, to obfuscate, or to just ignore the questions altogether.”

After five years of exerting pressure, Zeghers and Fitzpatrick were able to negotiate with Leslie Raymond, executive director of the Ann Arbor Film Festival, to have the organization begin paying screening fees. The festival was under tremendous pressure from filmmakers after Program Director David Dinnell was removed in 2016. While Raymond interpreted Fitzpatrick’s criticism as yet another prong of attack, the two eventually reached an understanding about his objectives and about where the impetus to change the festival came from. As for his choice to make Ann Arbor the object of a pressure campaign, Fitzpatrick says, “To me they’ve always been symbolic: they’re the oldest film festival in America, they play in a gorgeous theater; it’s been such a symbol for me.”

In Ann Arbor’s press release declaring that they would begin to offer fair pay to filmmakers, Leslie Raymond writes,

Artists pour money, time, energy, heart, and soul into their work, and are usually the last to see compensation. The paradigm that art is not worth money is wrong. Creative expression is good for society. Art adds value by connecting us to our humanity and our culture. It provokes us to think, feel, and see things in new ways. Art inspires and gives rise to more creativity. We all benefit.{14}

The press release credits Scott Fitzpatrick as the source of this change, while suggesting the path was forged by festivals like Alchemy Film and Moving Image Festival, European Media Arts Festival, Experiments in Cinema, Iowa City International Documentary Festival, Kasseler Dokfest, Milwaukee Underground Film Festival, and San Diego Underground Film Festival. Each has taken steps toward fair remuneration and/or engagement in advocacy around the issue.

Samara Grace Chadwick, a founding member of Independent Documentary Directors (IDD), observes that in the US many documentary filmmakers are in debt and are more reliant on elusive streaming deals, whereas Canadian and European documentarians are often more solvent and can make work without need for significant financial return. For Chadwick,

The entrepreneurial model of the American film landscape creates a competitive atmosphere that forecloses the idea of real collective interests. It’s been a challenge to articulate or advocate for collective interests because people feel so precarious; they will leap at the chance to save their own skin. I can’t tell you how many calls I’ve had this year with filmmakers who feel all their troubles will be solved if only Netflix or Sundance would answer their emails. The system is rigged to make it nearly impossible for people to think outside of their own self-interest. The American context is akin to a feudal state—no one is questioning the overlords.

IDD, an advocacy group of nearly two hundred directors, was created to respond to this crisis.

IDD’s collective efforts require something of an attitude adjustment for filmmakers who have embraced the independent in independent filmmaking, as well as for those who are anxious about rocking the boat. But as the ground shifts, filmmakers now have a newfound negotiating power, argues filmmaker and IDD member Larissa Lam: “We’ve been encouraging filmmakers to use leverage. [Festivals] need content. They need people to come and watch films, and I think submissions are down. As filmmakers, if you haven’t secured a distribution deal, you still have some leverage. I want to show my film to the world, but [festivals and distributors] need content.”

IDD emerged out of the same COVID context that gave some festivals grounds to justify more exploitative behavior. Documentary director Cecilia Aldarondo has argued for understanding this as a coefficient of disaster capitalism—the range of exploitation and adaptation of economic policies that the population would be less likely to accept under normal circumstances. Aldarondo says, “When I call it disaster capitalism, I mean corporations using COVID for cover—the perfect excuse to shut down institutions, fire people, and redirect their priorities in the pursuit of profit.”

COVID has also provided an immediate context for some of the organized pressure campaigns. One outcome is “The Film Festival Survival Pledge”—published by the crowdfunding and video-on-demand platform Seed&Spark—which has been signed by over 260 festivals.{15} Filmmaker and programmer Adam Sekuler offers a more pessimistic view on the permanence of these developments, however:

In my experience, this year has been the best year for compensation, because on some level there’s finally a mandate from festivals to support the filmmaking community. The way that it’s been worded to me from festivals is that it’s a temporary situation. This is some sort of goodwill gesture inside of the pandemic. I find that troubling, that they’ve even crafted the language that way, that the language is designed so that, essentially, they’re trying to say to the filmmaking community, “We recognize that you’re in trouble this year, but the paradigm that we’ve been functioning in is not one where we really consider your labor or even think about the value of what you contribute to our work, and the hierarchy is that we’re providing you a service, and you’re going to accept.”

Indeed, the shifts that are occurring now may be temporary. But they don’t have to be.

At the Tribeca Film Festival, a range of economic mitigation policies have gone into effect: the for-profit parent company Tribeca Enterprises shuttered their grant-making nonprofit arm, the Tribeca Film Institute, and laid off its entire staff; the six-figure festival prize money offered to 2020 films in competition was rescinded; and instead of holding the festival as they had programmed it, Tribeca set up a drive-in screening series sponsored by Walmart, and organized a festival on YouTube called We Are One as a fundraiser for the WHO. In both cases, the vast majority of 2020 Tribeca Film Festival filmmakers were left out of these initiatives and never had a chance in 2020 to regain their lost premieres. To its credit (and unlike SXSW), Tribeca did invite its entire slate of 2020 films to participate in the 2021 edition of the festival, over a year later. But in the chaos of the first months of the pandemic, major for-profit festivals nonetheless made decisions with lasting effects, not only for the filmmakers they had selected in 2020, but for the ecosystem as a whole. In contrast, at Rendezvous with Madness, Festival Director Scott Miller Berry has rerouted the costs of theatrical exhibition rentals into filmmaker payments. While the box office took a substantial hit at the festival during the pandemic, Miller Berry was still able to adequately remunerate every filmmaker through IMAA (Independent Media Arts Alliance) fees and ticket proceeds.

In my decade of film programming, I have watched countless filmmakers drop out of independent production and exhibition, too financially depleted and emotionally exhausted to continue working within such an onerous system. And yet, I think that festivals are too good a concept to give up on—that is, so long as we stop pitting what’s good for festivals against what’s good for filmmakers. For festivals to ensure viability and sustainability, they must build in revenue streams to benefit their own greatest benefactors—filmmakers.

Acknowledgments: This text benefited from interviews and discussions with Cecilia Aldarondo, Samara Grace Chadwick, Nazlı Dinçel, Sean Farnel, Scott Fitzpatrick, Maori Karmael Holmes, Larissa Lam, Terra Jean Long, Mads B. Mikkelsen, Scott Miller Berry, Adam Sekuler, Brett Story, and Aaron Zeghers. I would also like to thank Erika Balsom and Jason Fox for incisive editing notes.

*Some of the information and ideas in this text have come from individuals who have chosen to remain anonymous.

{1} By “disparate arms” I mean an infrastructure of distributors, press agents, buyers, vendors, advertisers, donors, boards, etc.

{2} See Ezra Winton, “Good for the Heart and Soul, Good for Business: The Cultural Politics of Documentary at the Hot Docs Film Festival” (PhD diss., Carleton University, 2013).

{3} Netflix and, increasingly, other streaming platforms are able to leverage their power to influence what’s included in a festival’s lineup. This used to be the province of movie studios, but both studios and streamers are now able to say, “If you want to premiere X film, you have to include Y film at the festival, too.” This fact mocks the meritocratic promise that festivals make in assembling their highly selective lineups.

{4} I want to avoid homogenizing all film festivals, given their vastly different scopes, missions, and financial means. These criticisms are especially directed toward larger festivals with significant operating budgets and revenues.

{5} W.A.G.E. explains its fee calculations as follows: “W.A.G.E. Certification sets minimum standards of compensation to be paid to artists for 15 fee categories. The level of compensation an organization must provide in order to be W.A.G.E. Certified is determined by its projected Total Annual Operating Expenses (TAOE) during each fiscal year. Fees for each category are calculated as a fixed percentage of an organization’s TAOE (when over $500,000) by W.A.G.E.’s Fee Calculator and are assigned to each organization as part of the Certification process.” More information is elaborated on their website: “About Certification,” Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.), accessed February 12, 2022.

{6} Mark Peranson, “First You Get the Power, Then You Get the Money: Two Models of Film Festivals,” Cinéaste 33, no. 3 (Summer 2008): 39.

{7} Sean Farnel, “Towards a Filmmaker’s Bill of Rights for Festivals,” in The Film Festival Reader, ed. Dina Iordanova (St Andrews, Scotland: St Andrews Film Studies), 223–29.

{8} This estimate was for Sundance 2020 and based on their published submission numbers and an average submission fee calculated by Farnel.

{9} “About,” BlackStar, accessed February 12, 2022.

{10} It’s important to note the difference in the position titles screener, programming associate, and programmer. These positions usually account for what films are screened, with screeners usually at the bottom rung, focusing on blind submissions that haven’t been solicited and are most prone to paying submission fees.

{11} Inney Prakash (@storebrandbrown), “I resigned from SXSW as a screener because they asked for a huge time/labor commitment without pay,” Twitter, February 18, 2021.

{12} Cecilia Aldarondo (@blackscrackle), “I learned today that @sxsw isn’t paying its 2021 filmmakers screening fees and is making them create their own Q&As at their own expense,” Twitter, February 17, 2021.

{13} The Canadian Artists’ Representation/Le Front des artistes canadiens (CARFAC) and the Independent Media Arts Alliance (IMAA) have designed fee schedules often mandated by grant providers to film festivals such as Canadian Heritage and federal and provincial arts councils. But grant providers don’t always enforce these requirements. When I asked Rendezvous with Madness Festival Director Scott Miller Berry why that’s often the case, he replied: “I don’t think it’s one thing. . . . It’s been said to my face that arts councils don’t want to be police. As big and robust as many councils are, they’re as strapped as any cultural organization. My opinion: lots of public grant organizations work on the honor system, blind-faith trust, taking them at their word.” Filmmaker and IMAA President Aaron Zeghers suggests that the Canada Council for the Arts doesn’t have the resources or chooses not to allocate them to check up on these organizations. Among the Canadian festivals accepting public funding, it’s almost always smaller festivals, with scaled-back operating budgets and profit margins, that do honor their grant mandates to pay artists.

{14} Leslie Raymond, “We Value Artists,” Ann Arbor Film Festival, accessed February 12, 2022.

{15} “The Film Festival Survival Pledge,” Seed&Spark, accessed February 12, 2022.