Film Unions and the Low-Budget Independent Film Production

Film Culture

This conversation was originally published in Film Culture, no. 22–23, in summer 1961.

****

The union situation is of particular interest to the [New American Cinema] Group. The discussion which we print here gives some insight into the existing relationships between the unions and the filmmakers. Once the problem is stated, summed up, a step forward will be possible. At this moment the Group is studying the union situation closer and is preparing its own proposals for the improvement of existing conditions.

Participants of the discussion: Willard Van Dyke, president of the Screen Directors International Guild; Lew Clyde Stoumen, writer and director; Shirley Clarke, director; James Degangi, producer and former president of the Assistant Directors’ and Script Clerks’ Local 161; Jonas Mekas, writer and director; Adolfas Mekas, writer and director; Gideon Bachmann, radio commentator on the WBAI Radio program The Film Art.

Interview

Jonas Mekas

The purpose of this discussion has several interrelated aspects:

1. To give a low-budget independent filmmaker some idea of the problems he has to face when he is producing a film with a union crew; what is that crew, what are the conditions of the unions, etc.

2. What problem does an independent filmmaker face if he wants to produce and distribute a film without unions.

3. To inquire whether anything can be done to facilitate independent low-budget film production on the East Coast. By now, it should be clear to everybody that the aims of the New York filmmakers differ greatly from those of Hollywood, and that a $25,000 or $100,000 production should be treated differently than a $1,000,000 production.

Shirley Clarke

Mr. Degangi, as the ex-president of Local 161, cannot speak officially for the unions. This doesn’t mean, however, that we cannot get from him the opinions that are held by the unions in New York City today. Right?

James Degangi

That’s right.

SC

This is a very interesting point: it is very difficult to get anybody from the unions to talk to. They do not want to talk officially, only privately. When a low-budget independent filmmaker wants to talk to the unions, he can never really get to talk to them. He is merely told that such and such are the rules and he has to obey them.

Willard Van Dyke

I don’t think that is quite accurate, Shirley. I think that if you wanted to talk to a representative of any union in New York, he would talk to you and tell you exactly what the union rules were. Then, in many cases he would indicate that there are possible exceptions under certain circumstances.

SC

Give me an example where this ever happened? My experience has been just the opposite. All that he could possibly do is to tell you what the minimum crew was. But he would never be able to negotiate anything but the requirements the union has.

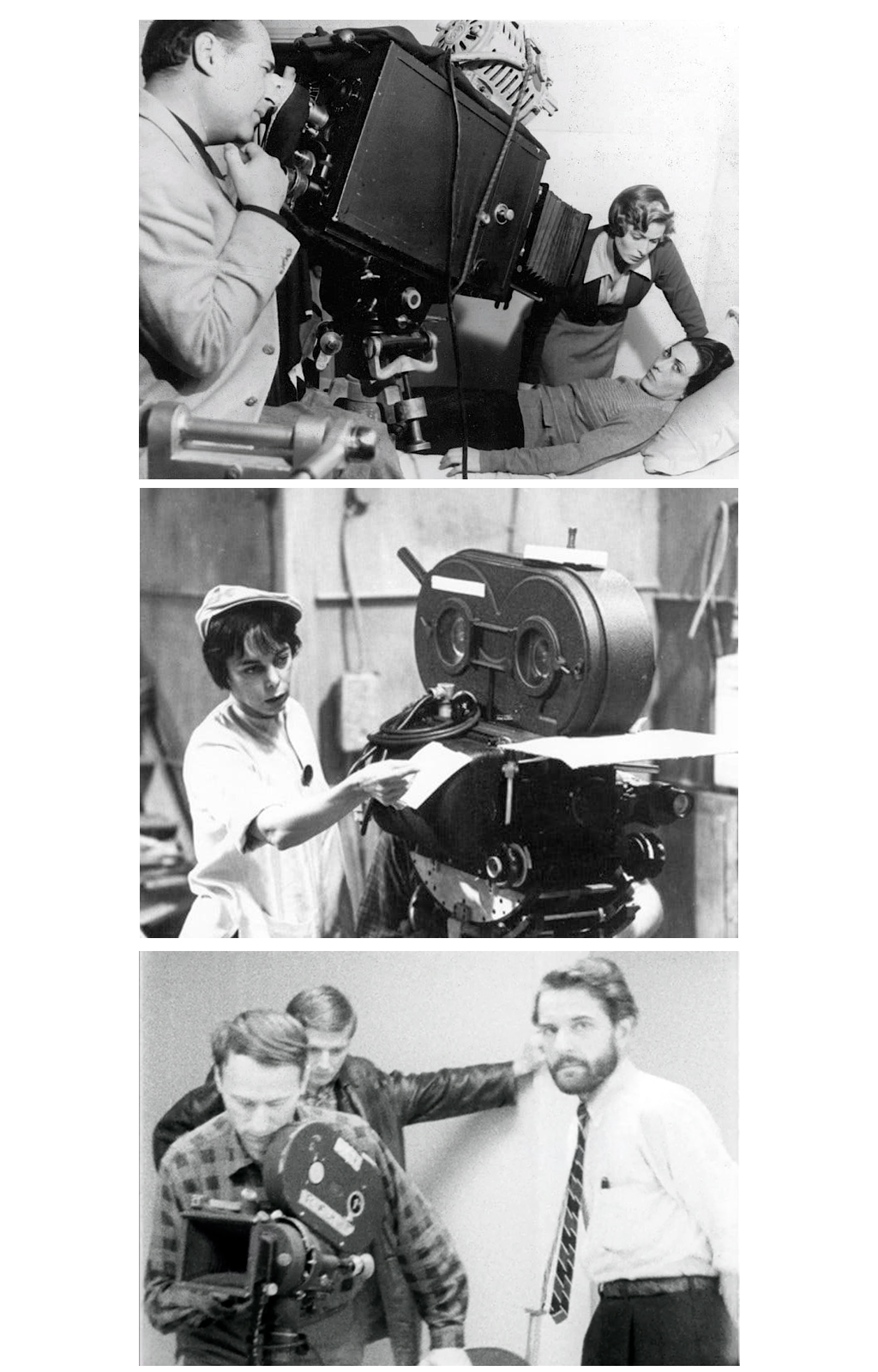

Shirley Clarke on the set of THE CONNECTION (Clarke, 1961). James Degangi is credited as a producer on the film. Image courtesy of Milestone Films.

Shirley Clarke on the set of THE CONNECTION (Clarke, 1961). James Degangi is credited as a producer on the film. Image courtesy of Milestone Films.

. . . THE SETUP OF THE UNIONS . . .

JD

It would be impossible for the union representative, who is usually a union delegate, a paid member working under the conditions established for him by the membership vote, to make any arrangements officially. That wouldn’t be in keeping with the rules that were written down for him to follow. He is merely a policeman of any situation, new or old.

WVD

Some people may not be aware that the film craft unions are divided into various locals: the cameramen have one local; the stage hands, electricians, property men, and sound men are organized into another local, Local 52. Then there is the editors’ local. All of these various locals in the New York area are part of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees which also has other locals under its control.

JD

Each local has a great autonomy. The International Alliance cannot take upon itself to make deals or exceptions to existing rules in the various locals without the approval of each individual local. The International Alliance acts really as a liaison between the producers and the locals. The locals set down their own working conditions. As long as those conditions are not in opposition to the established general constitution of the IA, the Alliance will say nothing. The trouble is that the crafts have never got together to standardize their working conditions in terms of any single production. This is the main trouble. To get a single representative, or a body that would represent all these locals, has been something on which all the locals and the IA have been working for quite some time.

. . . NO MINIMUM CREW . . .

SC

Could you tell us what is the minimum crew in New York on a feature theatrical film?

JD

The minimum crew, that’s a phrase which I consider false. There is no such thing as the minimum crew. The requirements of the craft locals are that, if the job exists, in any field, it should be done by a union person. The definition of the minimum crew amounts to the definition of existing jobs. If a man is necessary to operate a movie camera, other than the director of photography—the union stand is that the operator of the camera, the man who turns the wheels, aims the camera, composes the shot as the camera moves, that man must be a union member. It’s the size of the operation of the picture being done, and the speed with which it was necessary to operate, budget-wise, that decides the size of the crew.

. . . THE DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY MAY TOUCH THE CAMERA . . .

SC

It astounds me. The worst thing that could happen to any cameraman is to rise in his field and become director of photography. Because at that point he gets himself into a situation where he no longer is able to touch the instrument that he expresses himself through. It’s ridiculous.

JD

That’s not true, he can touch the camera . . .

SC

I have seen him touch it, but he cannot run it.

Lew Clyde Stoumen

I think it is awfully magnanimous of the unions to let the director of photography touch the camera.

I think the issue comes down to something like this: There is a general feeling among independent filmmakers that the unions stand between them and their art. And I am not interested in the industry, as it is called. As a filmmaker I am interested in art, and I use the word without apology. Throughout my whole professional career, the unions have been interfering with my work. More than ten years ago, in Hollywood, I acted as a director of photography on a film that was made non-union by Arch Oboler, Five [1951], released by Columbia. At that time I was a fairly good director of photography. I went down to the union, Local 659. Arch Oboler came with me. He said he wants to use me in his next picture. So the union man, Herb Valler, patted me on the back and said: “Well, I’ll tell you what. We’ll give you a card. You can be a loader.” In other words, I can load magazines for a couple of years; then, for a couple of years, I’ll get a card to follow focus; then, when I was ninety-five years old, I could operate the camera. And finally, when someone else dies, I could become director of photography, at the age of hundred and twenty. But I already was director of photography in my own work. So, I was effectively kept from working.

. . . UNIONS PREVENT FILMMAKERS FROM WORKING . . .

LS

Hollywood and New York film craft unions are closed shops. They are closed by the unions themselves. Some of the finest people in the various crafts are not able to work because, against the law of the land, and without any regard to the art of the film, the unions prevent these people from working.

SC

Why can’t the director of photography also move his camera? I’ve been there on the set and I think it’s possible. And it’s certainly very possible out on location where there are not as many light setups. We are not talking about Hollywood films. We are talking about films that look different, and are different than major Hollywood productions.

LS

If a man is capable in his craft, why should he go through twenty years of apprenticeship when some union stumblebum, who has a union card but is a mechanic, can work any time?

. . . THERE IS NO DIFFERENCE BETWEEN AN AUTOMOBILE AND A MOVIE . . .

JD

The answer is the same as it would be in automobile work: a man who designs the body of the automobile would not be permitted to perform some other functions.

SC

But there is a difference between an automobile and a movie.

JD

There isn’t any difference.

Gideon Bachmann

To put a bolt in an automobile is not a creative process. Maybe there should be unions for canvas stretchers, too . . .

SC

If a producer, for instance, wants to use a union cameraman, that cameraman could not work on his film unless the entire crew is union. You can never get a picture made, like you do in Italy, with a mixed, union and non-union, crew.

. . . CONCESSIONS ARE A LONG PROCESS . . .

JM

Are the unions aware, are they making any difference between the low-budget and high-budget productions? Are the unions giving any thought to this essential difference?

SC

Like Broadway and off-Broadway theater.

JD

It’s possible to get one of the crafts and make some concessions in terms of what they have in their books right now, in the way of rules. But it would be a long process to get all the locals involved, all of the crafts, for the mere fact that they just can’t get together on their conditions.

SC

If the director of photography wants to move his camera, can the union stop him?

JD

No. Absolutely no. As long as the job of an operator is covered by a union man.

SC

Who sits there.

LS

Suppose the director of the film wanted to operate the camera, as I generally do?

JD

There is nothing in the books that could prevent him from doing that, as long as the crafts involved are covered by the union men.

SC

As standbys.

JD

That’s right. Exactly.

LS

In other words, featherbedding.

JD

Standby is not featherbedding. The object of the union is not to force people on the producer which are not necessary.

IN PARIS PARKS (Shirley Clarke, 1954).

IN PARIS PARKS (Shirley Clarke, 1954).

. . . A TREE SHOT THAT TOOK SIX UNION MEN . . .

JM

At this point, could you, Shirley, give your example of the tree, you know what I mean?

SC

I wanted to find out what were the minimum requirements of the unions—that was two or three years ago. I picked up the phone and I spoke with someone in the cameraman’s union local. And the conversation went like this: “I want to photograph a tree in the woods, and I would like to know, what is the minimum crew that I need?”

They said:

“Camera operator, an assistant, two electricians, and two grips.”

And I said:

“That’s interesting. What do the grips do?”

“Oh, they are in charge of moving things around.”

“But the tree is standing there. . . . What about the electricians?”

“They are in charge of the lighting.”

“Well, it’s sunny out.”

Anyway, the thing was very silly. The point was that under the existing conditions there were six people to make a shot of the tree that could be made by one person, going there and opening his camera on the tree. If I put an actor in front of the tree, I still don’t need anybody’s help. In other words, the need at that moment was not for six people standing there doing nothing. But it was the minimum union requirement.

To put a bolt in an automobile is not a creative process. Maybe there should be unions for canvas stretchers, too . . .

. . . ROSSELLINI AND HIS SCAB JOBS . . .

JM

Rossellini was able to shoot a film with only four union people; he was working with Italian unions. That was their minimum. They change their requirements according to the nature of the film and its budget. That’s what we need for the independent filmmakers in New York, and nothing less.

GB

The attitude of the union members themselves towards these questions is important. Is there a fear on the part of the unions that if they don’t police their rules, they will be out of jobs?

JD

That’s exactly so. A lot of people are not aware what the conditions were in the industry when this industry began. Mr. Mekas speaks about Rossellini, Italy. The answer to this is, that as a result of strict working conditions and a little forethought on the part of the people who helped the unions in this country to grow—the conditions of the working man in this country in the motion picture industry are a little bit better than the conditions of the working man in Italy. There he has no other place to go until Mr. Rossellini offers him a scab’s type of job for peanuts or no money or maybe a percentage of the film.

(general uproar . . .)

A Voice

This is an outrageous statement.

JM

Rossellini works only with the best people. It is an honor for a cameraman to work with a man like Rossellini.

JD

We are not discussing the merits of what is going on the canvas. What we are talking about is how to do it best with hurting the least number of people.

JM

Filmmakers are not people . . .

SHOOTING GUNS (Charles I. Levine, 1966). Footage documenting the making of Jonas Mekas’s 1961 film, GUNS OF THE TREES, recorded by Charles Levine.

. . . UNIONS PROTECTING MONOPOLIES? . . .

JD

In answer to Shirley, to what I hope was a facetious request . . .

SC

I wasn’t going to shoot the tree . . .

JD

I understand it as a situation in theory only. The answer of the unions is very simple. The producers with whom they have contracts, and with whom they have negotiated and are working under certain conditions, have to be protected. Concessions for the same kind of shooting cannot be made to somebody who in turn could be in competition with these producers who are helping the union to exist and to grow.

. . . NON-UNION FILMS . . .

JM

What will happen if someone wants to shoot a film without unions? How would this affect the distribution of the film?

WVD

Let me say this: Isn’t it true, that there have been three feature films made non-union by one independent producer in New York that played in New York theaters?

JD

There have been many features on New York screens made non-union. No question about that. I consider this a very silly fear on the part of many people. All kinds of seals and things that people worry about. We know that non-union films have appeared on the screen, nationally, internationally, and especially in New York. Nothing will happen if you decide to shoot a film non-union, if it has value and the man who owns the theater likes it.

Adolfas Mekas

That’s right, nothing will happen: they will simply block you from all sides.

JD

If the man who likes it decides to put it on the screen, it becomes a matter of money only. The issue will be raised, in many cases, and if the producer and the owner back down and do not stand up for their rights, of course, the people involved will take the easy way and will go along with the established rules.

. . . THE PROJECTIONIST AS A UNION SWORD . . .

JM

A few weeks ago, there was a film by Gregory Markopoulos, an experimental film, projected in a commercial theater. As soon as the union projectionist found out that the film was non-union, he stopped the projector in the middle of the screening, and nobody could do anything about it.

JD

Because it is wrong to expect a man to go against the rules of his union without talking to his union about it first. If you know that you have a non-union condition, in any serious place, don’t go to one member of that union and expect him to sanction your non-union operation. That must be done by negotiation with the organization that represents that man.

SC

This is bribery.

JD

It’s not bribery. If I have a picture which is made non-union, I would not naively expect a union projectionist to go in complete opposition to the rules that have been set for him as a member by his organization to run this film.

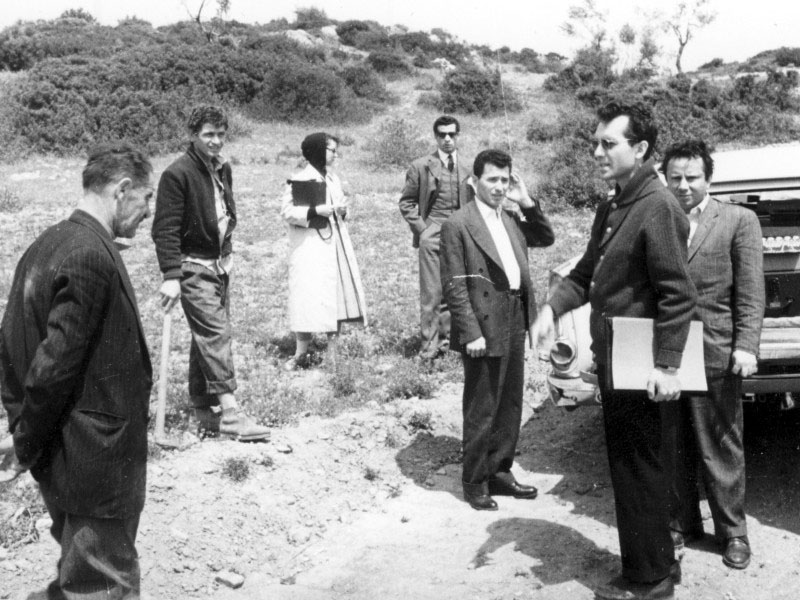

On the set of SERENITY (Gregory Markopoulos, 1961), filmed in Mytilene and Annavysos, Greece, 1958.

On the set of SERENITY (Gregory Markopoulos, 1961), filmed in Mytilene and Annavysos, Greece, 1958.

JM

You contradict your statement that “nothing will happen if you decide to shoot a film non-union.” What could be worse for a film than its being prevented from being shown? And no independent filmmaker wants—or is able—to pay money to someone who did not move a single finger to make his film. Why should he pay money, why buy a seal from a union?

SC

I could tell you stories and stories about how the filmmakers get their seals. I know one—and we are not mentioning names here—who paid $1,000 for a short documentary.

LS

It’s criminal. He will never get that much money back with a documentary.

AM

The only thing to do is to shoot the film, forget the union. We don’t have to show our films here—the world is wide. We can show them in Europe. If the film is recognized, no union will be able to stop it from being shown anywhere you want.

SC

If I could get my films played without any trouble from the projectionists, I personally would have nothing to do with the unions.

GB

The projectionist is the only sword that the unions can wave at the independent filmmaker.

LS

I think this is against the law too.

JD

It’s the lawyers’ law.

LS

I think when the various craft unions threaten, “All right, you sonofabitch, go ahead and make your film, but our projectionist is not going to show it for you,” this kind of threat is extra-legal.

. . . IS THE UNION SEAL ILLEGAL? . . .

SC

You buy a seal, you pay a penalty to the union, and it’s illegal again. . . . It’s bribery.

JD

It’s legal. This condition was set up in the books by negotiations with some other producers who make films and want to distribute them. You negotiate with the organization that controls the working conditions.

A Voice

It’s bribery. The government controls the working conditions. Who gets the money that comes from buying the seal?

JD

The money that comes from buying the seal goes into a welfare fund of the union, and it goes to out-of-work members. This money doesn’t go to any supposed racketeer or anything like that.

The trouble is that the new producers think that one representative of one of the locals represents the whole union. This is a ridiculous way to try to negotiate and make pictures with labor organizations, in this town, Hollywood, or anywhere else. The thing to do is to go to the local, set down your problems, and have the council or the executive board come with an answer about the particular craft which they represent.

. . . UNIONS ARE OK, BUT SHOULD THEY STRANGLE FILM ART? . . .

LS

I think there is no disagreement on the value of unions in industry in general and in the motion picture field in particular. Without question, the protection by the union of the working man in all the crafts protects him from exploitation. But there is a basic agreement among experimental and independent filmmakers that,

1. Craft unions strangle the art of film very often by making economic restraint an artistic trait;

2. The unions indulge in extra-legal and illegal activities. Some work could be done in this area. It’s no accident, for instance, that it’s not possible for an independent producer to speak to a representative, a single representative, a general authority on all the union requirements.

JD

No such thing exists.

. . . THERE SHOULD BE SPECIAL PROVISIONS FOR LOW-BUDGET FILMS . . .

LS

I know. And this is no accident. Everybody plays against everybody else. Then there is a question, which Jonas raised, that in other countries it is possible for a small independent producer, a man with ideas and with very few dollars, to try something new and fresh and to do so within the bounds of economic possibilities. In this case, when we are dealing with low-budget and often experimental productions, where there is so little money involved, nobody touches even the skin of the unions. Something could be done to change the impossible requirements of full crews, standbys, with no “go and shoot, but you certainly will not get it distributed” and all that business. Unions had better wise up that there are things happening in film production in foreign countries which are cutting into their own market here. Just from the viewpoint of economic self-interest, there should be a special provision for experimental and low-budget productions so that the local producers in an honorable way could deal directly with the unions and the unions deal honorably with them, under a very special body of rules.

. . . BORIS KAUFMAN CANNOT WORK IN CALIFORNIA! . . .

WVD

What would you like the unions to do, what kind of concessions are you talking about?

LS

For instance, if I were shooting a film in Hollywood and wanted to hire a man, who in my judgment is the greatest director of photography, Boris Kaufman, I could not hire Boris Kaufman to work in California. I have a script and I would like to shoot it in California, and I want Kaufman to do it. He can’t work there because he is a member of the New York local! Now, I won an Academy nomination for a film on which I used a cameraman from a Chicago local. He worked on my film under an assumed name, because we shot it outside the jurisdiction where he was authorized to work. I want a freedom that a man can work in and out of the union. If a man has talent, I want him to be admitted to the union, because I want to hire him. And I don’t see why not. It is against the law that a man cannot get a job because he is not a member of the union.

Excerpt from THE PHOTOGRAPHER (Willard Van Dyke, 1948).

. . . THE ILLEGAL ACTIVITIES OF THE UNIONS . . .

LS

Coming back to my earlier example, when Arch Oboler wanted to hire me to do photography on his film and we went to the union, the union man said, “You can’t.” I said, “Well, that’s the law.” He takes me to a shelf of books and he shows me a series of legal briefs all the way up to the Supreme Court, and says, “Look, buddy. If you have thousands of dollars and several years, maybe you can win this case. But we are able to fight it up to the Supreme Court and you are not going to do that picture; one of our own boys is going to do it.” I want freedom to work with whomever I want, without the unions saying, “You can’t use that guy, he doesn’t have a card in our local.”

I also want to use the number of men that I deem necessary. The way I work, for instance, it’s a sort of intimate way, I want as few people on the sets as possible. With all the grips and electricians, etc., around, you destroy the intimacy of the situation. I want to work with the cameraman, the sound man, and as few other people as possible. As the artistic creator of the film, I want to be able to determine the conditions of my production, which is more than fair to ask. And I want to achieve this by straightforward dealing with the unions. But the unions are not making this possible for me or anybody else.

. . . UNNECESSARY PEOPLE ON SET . . .

SC

For instance, on the set of The Connection [1961], we had at least three people that sat there most of the time and really had nothing to do. I don’t know them, some of them I never saw. There was one person who was called set painter. Now, because of the style of my film, this would be the last thing that I would do, to paint the set. It should be made possible that if I need, I can call the union and get a man for one day or one hour to do some painting, if needed. But there is no reason for him to sit there all the time and play cards. There was the whole mess in the cameraman’s union, too. We got really messed up in the still photography, because we could not get the man we wanted, and they insisted we take another man who was just no good.

JM

How many union people did you have on the set?

SC

Some twenty people at least, twenty-two I think, something like that, because some of them I never saw, I don’t know who they were, those people. At least five of them were unnecessary. It makes a big difference on a low-budget film.

Only individuals make the world.

. . . THE GUILDS . . .

JM

Do the guilds have similar attitudes and policies of working?

SC

For instance, we had to be sure to finish shooting within thirty days, because if we didn’t, all our actors would have to join the Screen Actors Guild and that would cost us another $600 per actor. We couldn’t afford to do that so we had to hurry and be finished in thirty days.

JM

But you wouldn’t say that the guilds are as strict and unreasonable as the film craft unions?

SC

Oh, no, no comparison.

LS

I think it should be put on the record here, that the requirements of the guilds are more reasonable. The Screen Actors Guild, for instance, is a wide-open guild, with a reasonable initiation fee and regular dues. The Directors Guild, I understand, is also a wide-open guild, although its initiation fee is higher. The Writers Guild has a modest initiation fee and the only requirement is that you do some professional work as a screenwriter. The film editor’s union, and the film cameraman’s union, these are closed clubs. The most talented people of this country are most possibly not in these unions. It is not possible to get into them except by luck or nepotism.

. . . AWAY WITH UNIONS! NO TIME FOR NEGOTIATING,

WE HAVE TO MAKE FILMS . . .

AM

The only thing to do, is to do away with the unions, and start all over again, from the beginning . . .

SC

Organize them . . .

AM

. . . modern way, 1961.

SC

We’ll organize them . . .

JM

Shoot them . . .

AM

Let’s ignore them. The only thing to do—just ignore them. The unions can throw their cards away or keep them as souvenirs. Unions are an anachronism in 1961.

JD

I could tear my card up right now, if I wanted to. But it would be my choice. If I decided to work on what my union at the present considers a non-union job . . . but that would be my individual choice.

AM

Only individuals make the world . . .

We’ll negotiate with the unions in ten years. But now we have to make films. No time.

JD

Then negotiate with the individuals that have guts and fire to tear up the cards and do what they like to do.

A Voice

I don’t believe in any cards.

A Voice

Cards are illegal.

A Voice

Let’s give cards to everybody.

A Voice

I don’t give a shit.

. . . INDEPENDENT FILMMAKERS WANT TO DEAL IN AN HONORABLE WAY WITH THE UNIONS . . .

WVD

There are two attitudes here: One is, to hell with unions, we’ll work without the unions, destroy the unions. The other seems to be: Let the unions change . . .

SC

. . . and become non-unions . . .

JD

You cannot change so many people. It’s ridiculous.

LS

We independent filmmakers want to work in an honorable way with the unions. What I ask is that the unions obey the law of the land, which is, if a man gets a job he should be allowed to work. All I ask is that the unions obey the law, and I am goddam mad about it.

. . . WE NEED $2,000,000 TO FIGHT THE UNIONS . . .

SC

Why don’t we raise a couple of million dollars and take them to court? . . .

A Voice

That’s the thing to do.

LS

Let them stop all this hypocrisy and sanctimonious nonsense about protecting the worker; let them obey the law of the land.

SC

We got here another revolution going . . .

Still, the unions should realize that we are in New York City, and in 1961. New York is in a different position because of what is going on in the overall industry. NY industry is very touchy. It just lost all its TV shows, it lost almost its life . . .

A Voice

Good!

. . . UNIONS COULD HELP TO MAKE NY INTO A FILM CITY . . .

SC

Hollywood is not making movies anymore, they make TV now. The moment has come—here, right here, and now—for the unions to take advantage and make a real rip-snorting film industry in New York. Oh, boy. . . . But it can be done only if the union helps us.

JD

The unions are not unaware of it.

. . . MORE ON UNIONS AS CLOSED CLUBS . . .

SC

You know, they wouldn’t accept an application from me, as an editor, for the last four years. And then they insisted that I apply in order to be allowed to edit The Connection.

LS

Isn’t that ridiculous?

SC

But when I’m accepted, I shall refuse gracefully.

LS

Where is the justice of such limitations of membership?

. . . THE ANTIQUATED UNION LAWS . . .

JD

These existing conditions were not just pulled out of the air. A lot of the conditions that were established years ago still exist, in terms of the number of people, and what they do, and under what conditions they work. Because they were negotiated out, and they are kept on the books, like many other old rules and laws in New York City. You can be arrested for doing almost anything. It is true that a lot of these conditions don’t necessarily apply to what must be considered exceptional cases in today’s industry, and the only way the changes will be made is by airing these problems and negotiating them. Because these are recognized crafts. If we want to do something constructive about it, we must not take the word of individuals in these crafts—there are people in all craft unions who are concerned with only themselves, like in any other industry. The conditions in Local 52, for instance—stage hands—they have been established over a long period of years to solve particular problems that no longer exist. We must sit therefore with the unions and talk out the problems. Nobody is giving them a chance to come with some ideas about how the crafts could be adjusted to the necessities of a new kind of industry. They are living under the old conditions, because nobody has tried to change them.

. . . UNIONS ARE READY FOR CHANGES . . .

WVD

Basically, the complaints today have been voiced against the IA locals. But we should realize that these locals have a great deal of autonomy. Each of them has a great latitude in making its own rules. I feel that the leadership of IA here in New York knows that there are certain revisions that could be made in the working rules today by the locals. But the demands have not been strong enough for that kind of change.

. . . IS THERE NO DIFFERENCE BETWEEN $100,000 AND $3,000,000? . . .

SC

During the making of The Connection, I went through an experience which can show where some of our problems will lie. I went to the representative of Local 624, Jay Rasher, to talk about a still photographer. Now, it so happened that in the cameraman’s union there are only six still photographers. Rasher, he personally understood what I wanted and needed, that we couldn’t take a union left-over third-rate photographer, etc. Rasher had to go to his board, and his board is made of a lot of old-time guys sitting around, who are involved in protecting their jobs. Even if the union representative understood our situation and wanted to help us, he could not. His board met and his board said NO. Many other times we needed various things changed, and we went to the unions, and we didn’t get them. We didn’t get a single concession on a film costing $150,000 compared to the films costing $3,000,000. They expected from us exactly the same.

JD

Still, we were able to make The Connection with only $150,000, and, I think, we went even under that.

JM

The fact that The Connection was made within unions doesn’t mean much to the low-budget independent filmmaker. I started my film with only $6,000, for instance. I wanted to use some union people, to have more “craft” in some of the areas—but how could I even dream about the unions with this budget? With my 200 locations and six-months shooting schedule, it would have cost me a million, to work with unions. And most of the independent low-budget productions are made with $30,000–$60,000.

SC

The truth of the matter is that in New York now a very exciting movement is starting, a movement of filmmaking that will benefit the entire NY area, right down to the guys who are making commercials. And it’s time that the unions realize it and work out something.

Trailer for THE CONNECTION (1961), directed by Shirley Clarke and produced by James Degangi.

. . . UNIONS ARE WILLING TO NEGOTIATE, BUT A PLAN IS NEEDED . . .

JD

I think that a committee formed of serious people, who have plans and projects, things that they really have and want to do their own way—who want to make different films than the industry is accustomed to seeing—they must get together and work out a plan. Rather than going with a general discussion, such a committee should go with a well-prepared plan for the future, they should explain how they think they could make their particular films. Get the ball rolling.

. . . THE EFFECTIVENESS OF EAST COAST COUNCIL . . .

JD

They could go, for instance, to the East Coast Council that represents the IA locals involved in motion picture production, have the council invite the representatives of the non-IA crafts, that also are involved in the making of motion pictures, including teamsters, for instance—

Voices

Oh, boy!

(laughs)

JD

. . . they drive the theatrical trucks. . . . It’s a very effective working body, this council. But nobody has taken advantage of it. It’s been in existence for quite some time. I think that the locals themselves have much respect for it. Because it is not always possible to get to the leadership of the IA itself. The council brings them to the leadership.

LS

Are these people gods? What do you mean, it’s impossible to get to the leadership?

JD

They are not gods. . . . Then this group or committee could get invited to the locals at the membership meetings, to the council meetings, etc.

SC

They will laugh at us . . .

AM

They better don’t laugh.

JM

They will not laugh: there are too many of us.

JD

Not when this committee will have the authority and backing of a larger group of filmmakers.

JM

There is such a group. The New American Cinema Group, to which most of the East Coast filmmakers belong, is studying the union situation and is preparing proposals for necessary changes. It will go and talk with the union when these plans are ready.

AM

And this group is a new breed of people. They are not producers, not cameramen, not teamsters: you cannot split them into locals: they are filmmakers.

LS

I think the whole thing is hopeless.

JD

It is not hopeless. Believe me. Knowing the situation within the unions in this city and in Hollywood, I say that it is not so hopeless. I don’t think anybody ever tried it. Everybody always did it by opposing. You cannot win by opposing only. You have to propose, negotiate.

. . . THE SITUATION IS NOT SO HOPELESS . . .

. . . THE SMALL FILMMAKER VERSUS BIG BUSINESS . . .

JM

I agree with Mr. Degangi. Life is action, things are made and changed by action only. I know we can do it.

WVD

It is entirely possible for the film producers to sit down with the labor organizations and work out a fair contract, a contract that everyone agrees is a fair contract. I have sat through some of such negotiations, and I have seen them work.

SC

Big producers have never any difficulties with labor. It is the small filmmaker that has. When a big producer negotiates, there are many jobs involved, many things cooking. But when a small low-budget filmmaker comes and asks for something on a broad industry basis, no one will think it matters much, that’s why I say they will laugh at us.

There is a difference between a $1,000,000 production and a $100,000 film. And it will be the $100,000 film that will make the industry stay alive. It will feed into certain things that will make $1,000,000 productions possible. . . . The unions, the industry, should not cut their own throats. You see how much care and understanding we give to the industry. . . . Will the industry have so much understanding for us? We need Broadway’s off-Broadway understanding in the motion picture industry. We can talk only on that level.

Transcribed from a tape-recorded interview.

February 25th, 1961.

Title video: VALLEY TOWN (Willard Van Dyke, 1940), BRIDGES-GO-ROUND (Shirley Clarke, 1958), HALLELUJAH THE HILLS (Adolfas Mekas, 1963), WALDEN (Jonas Mekas, 1969).