The Conversation: Listening and Eavesdropping across Generations

Fadi A. Bardawil

I feel bound to acknowledge this publicly, so that “the tailor’s labour (does not) disappear . . . into the coat” (Marx), even into my coat.

—Louis Althusser{1}

I.

Listening is a demanding task. The ear, musicians say, is a like a muscle. It can be trained. The ear’s capacity to recognize tonal intervals, detect modulations between scales, catch off-key pitches, take note of rhythmic transitions, and follow chord changes can be developed to a great extent. Listening after ear training is a practice of heightened sensorial and intellectual acuity. The distinction between passivity and activity which is usually drawn on to articulate the contrast between hearing and listening is only the tip of the listening iceberg. I have a musician friend whose ear is so refined, and his attunement to the music so heightened as a result, that he can detect the slightest variation in pitch and inconsistency in tempo. Being submerged in music can simultaneously engender a heightened enjoyment in tandem with irritations he can hardly avoid. His discerning ear augments both his perceptiveness and vulnerability. It certainly contributes to making him a refined musical critic.

Critics, however, are not typically associated with the practice of listening. Ocularcentrism reigns supreme in acts such as unmasking, unveiling, exposing, revealing, showing, unearthing, turning upside down, demonstrating, and shedding light. Today, activists and revolutionaries are also predominantly on the side of the eye. They spend considerable energy building image archives both to criticize state propaganda machines and to marshal evidence to incriminate regime violence in a longed-for judicial process to come.{2} Last but not least, theory also belongs to the ocular register. It comes from the Greek word theoria—contemplation, speculation—which is derived from theoros—spectator. “Sight,” David Scott writes in commenting on “The Nobility of Sight,” an essay by Hans Jonas, “is the basis for neutrality and mastery, and timelessness, and consequently for theoria, or theoretical truth. By contrast, hearing is bound to the unstable passage of time, the contingent, uncertain experience of temporality.”{3}

The critic as the great unmasker is endowed with heroic qualities.{4} Listeners, except maybe for great psychoanalysts, rarely achieve such status. There is a momentary self-effacement, a bracketing of one’s own preoccupations, that accompanies the listener’s absorption in, and by, their interlocutor’s speech. They redirect their entire selves to their interlocutor and stretch their ear toward them. Tendre l’oreille, the French expression for listening attentively, captures well this redirection and extension of the ear.

****

II.

Having said that, not all forms of attentive listening are dialogical and entail a momentary letting go of the self. Eavesdropping, for one, is a mode of attentive listening associated with phone-tapping state surveillance operators and the perverse pleasures of minor transgressions.{5} Besides, the critical self is rarely associated with the figure of the eavesdropper. That said, this figure makes a brief, but I think significant, appearance in the afterword Edward Said wrote to the 1994 edition of Orientalism. Nearly two decades after the book’s first publication, Said revisits its reception and rearticulates its positions. In a moment of self-disclosure probably facilitated by the radical transformation Orientalism effected on disciplinary landscapes, and in reference to Orientalists as different as Gustave Flaubert, Lord Cromer, Ernest Renan, and Lord Balfour, Said writes,

I must confess to a certain pleasure in listening in, uninvited, to their various pronouncements and inter-Orientalist discussions, and an equal pleasure in making known my findings to both Europeans and non-Europeans. I have no doubt that this was made possible because I traversed the imperial East-West divide, entered into the life of the West, and yet retained some organic connection with the place I originally came from.{6}

What brings these radically different figures together, according to Said, is that they all “condescended to and disliked the Orientals they either ruled or studied.”{7} Said’s capacity for eavesdropping is, of course, an unintended consequence of his Western education, which endowed him, the colonial subject, with the capacity to move along the divide.

Those from the colonial world who were not addressed by Orientalists and were not the intended audience of what was written about them escaped their designated slot as objects of study. They became students in metropolitan universities, before becoming the colleagues of anthropologists and Orientalists who were well established in their authoritative disciplines. The transformation in the racial demographics of the metropolitan academic body disturbed the strict linguistic, institutional, and geographical boundaries separating the objects of inquiry from its subjects. This was not a seamless process. The young men and women who headed West from the colonial world to study confronted racist and misogynistic attitudes and texts, which were endowed with the authority of objective knowledge, science, and the universal.

The critical languages on the relationship of knowledges to power had yet to be articulated. Leila Ahmed, who studied at the University of Cambridge in the 1960s, poignantly registers the fundamental disconnect between, on the one hand, the personal experiences of students from the colonial world—and the suffering which accompanied them—and, on the other, the structures of academic labor and the white male canon.{8}

Said’s book, which followed in the footsteps of earlier critics of Orientalist scholarship such as Talal Asad, Anouar Abdel-Malek, and Abdallah Laroui, provided one critical language to bridge the gap between experience and scholarship by listening to what lies beneath the surface of discourses cloaked with scientific authority. In a memorable sentence in the introduction, Said draws on psychoanalytic concepts to reveal the logic animating Orientalist works:

Additionally, the imaginative examination of things Oriental was based more or less exclusively upon a sovereign Western consciousness out of whose unchallenged centrality an Oriental world emerged, first according to general ideas about who or what was an Oriental, then according to a detailed logic governed not simply by empirical reality but by a battery of desires, repressions, investments and projections.{9}

The tables were now turned. The objects became subjects. And the mappers were now mapped. The opening sentence of Talal Asad’s discerning review of Orientalism captures the reversal of roles taking place in the Euro-American academy around that time, as well as the defensive reactions this reversal led to. Orientalists, Asad writes,

have traditionally been concerned with describing, criticizing and characterizing the writings of Muslims and Middle Easterners which are thought to be representative of the society and culture in which they are produced. However, orientalists and their intellectual allies do not take kindly to similar exercises being carried out on their own literary productions. The sense of indignation which has been provoked in various academic quarters by the publication of Edward Said’s excellent study Orientalism . . . is perhaps itself an indication of the orientalist attitudes he has attempted to describe.{10}

Said’s perverse double pleasure—first, eavesdropping, and second, divulging—says a lot about the psychoaffective drive propelling his infiltration operation into Orientalist lines to leak, expose, and undermine. The critical gesture of the leaking eavesdropper bears structural similarities to the practice of “fadh (exposing, making a scene, shaming, causing a scandal),” which Tarek El-Ariss has recently analyzed and brought to bear on Orientalism.{11} What Said was after in his critique of Orientalism, El-Ariss observes, was “hacking it and leaking out its manuals and codes, and making a scene of its fantasies.”{12} In the wake of the scandal, those on whom the tables have been turned are expected to be silenced, after speaking on behalf of “Orientals” for generations.

This critical move is deeply subversive. For someone who was seriously concerned about the question of beginnings, Said was instrumental, through Orientalism, in bringing certain scholarly fields close to an end.{13} A senior colleague of mine whose training in religious and Islamic studies began in the early 1970s used to jokingly refer to himself as a “recovering Orientalist.” A discipline turned into an affliction. Said’s subversive and all-encompassing gesture was facilitated by his externality to, and distance from, the field he undermined. Neither his disciplinary training nor his institutional affiliations had to do with anything “Oriental.” He was no heir to this scholarly legacy who, like my “recovering” colleague, had to struggle with what became overnight a problematic inheritance.

As a result, after eavesdropping, Said worked his critical scalpel through the thick webs of Orientalist discourse without much resistance or hesitation. Said’s operation succeeded, at least in major quarters of the academic world. The eavesdropper ended up being one of the last listeners to Orientalists. Eventually, the word Orientalist no longer designated a member of a caste of authoritative scholarly experts. By the time my generation began its training in the social sciences and humanities of the modern Middle East, in the last years of the twentieth century, Orientalist had become equivalent to an academic slur.

****

III.

Said’s listening-for-leaking subversive operation comes to mind when I think of the historical and ethnographic work I’ve conducted over the years with Arab intellectuals who were Marxist militants in the 1960s and 1970s.{14} In my case as well, there was a lot of listening involved—a literal attentive listening as I conducted extended life-trajectory interviews with members of this generation, and a more figurative listening as I directed all my attention to the conversations these members were undertaking in theoretical works, political party bulletins, journal articles, newspaper editorials, and memoirs. Said’s operation comes to my mind precisely because it is the obverse of what I was undertaking. It serves as an exemplary counterpoint to my work on all fronts: eavesdropping vs. listening; dissecting vs. conversing; distance vs. closeness; undermining vs. reconstructing; condemning vs. rescuing; interrupting vs. gathering.

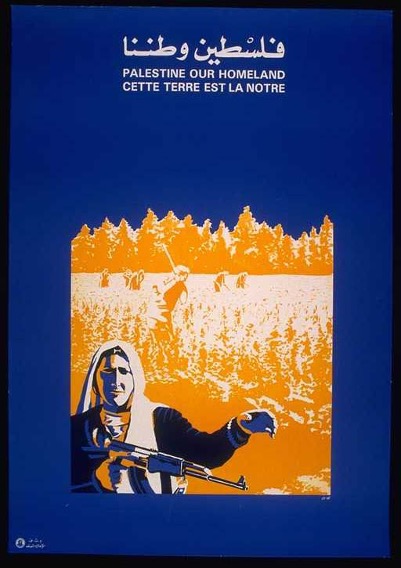

Palestine Liberation Organization poster (ca. mid-1970s) by the French artist Claude Lazar.

Palestine Liberation Organization poster (ca. mid-1970s) by the French artist Claude Lazar.

When Said entered the conversation scene, Orientalists were housed in universities with dedicated departments, specialized library collections, and occasionally museums at their disposal. Scholarly circuits, mentoring activities, and citational practices, in addition of course to their metropolitan institutional locations, all contributed to making their works about the Orient authoritative. On the other hand, the excavations I was undertaking were of lost worlds that were never institutionalized and whose debates, militant experiments, and theoretical articulations were for the most part forgotten. This was the case despite the fact that my interlocutors have become authoritative public intellectuals and thinkers in the wake of their exit from militancy.

In contrast to Said’s cool dissection of the entanglements of Orientalist texts with imperial power from the somewhat shielded, because unattached, distance of a scholar of English literature, I had to get as close as possible to the voices of my interlocutors to engage in the labors of excavation and reconstruction. I had to listen deeply, not only to their own narrations of themselves and their critical reappraisals of their political practices and theoretical positions, but also to the grain of their voices, their pitches, their silences, and at times their unsuccessful attempts at choking back a tear.

Getting close to the political and intellectual worlds this generation inhabited from the 1950s to the 1980s was certainly not a unidirectional movement from a fixed anchor point in the present. To listen deeply to their multiple narrations of their pasts was also to enter into a conversation about how their retrospective interpretations of those pasts informed distinct understandings of, and positionings in, the present. As these pasts were configured and reconfigured during our conversations, our present’s contours were drawn and drawn up again. The pasts bled into the present. Put another way, the relation between the present and the past, in particular the Lebanese civil and regional wars of 1975–90, and the pivotal years leading to them (1969–75), was still raw. That wound was still oozing more than fifteen years after the official declaration of the beginning of the postwar era. And I underscore pasts in the plural as a way of indicating that the cut has yet to scab over.

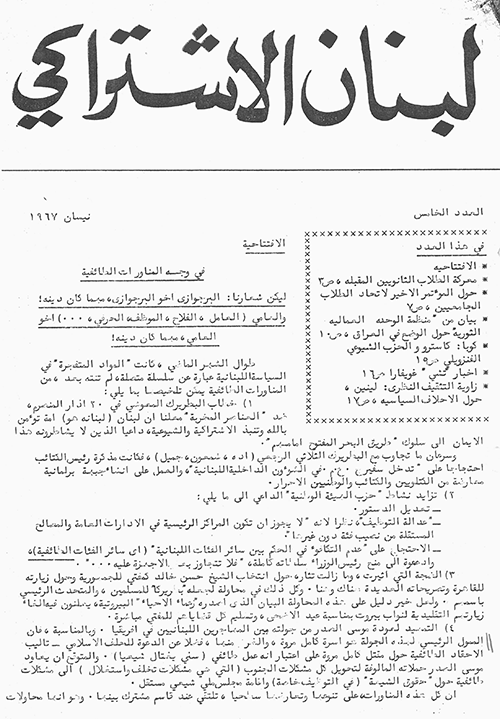

SOCIALIST LEBANON issue 5, April 1967. Mimeographed underground bulletin of Socialist Lebanon, the Marxist organization (1964–70) my work focused on.

SOCIALIST LEBANON issue 5, April 1967. Mimeographed underground bulletin of Socialist Lebanon, the Marxist organization (1964–70) my work focused on.

As I sat across from my interlocutors, my conversational posture was not far from John Stuart Mill’s understanding of the listening self who, as Christopher Bollas writes, has “to endure the full weight of the other’s points of view, not simply as cognate phenomena—intellectual objects—but as powerful emotional experiences.” This view, Bollas notes, “could easily be the credo of the psychoanalyst who, from his position of neutrality, must subject himself to the full force of the analysand’s emotional life if he is to understand the unconscious truths embedded in his statements.”{15}

And yet I was nothing like Bollas’s neutral psychoanalyst. Engaging in conversations with distinguished scholars and public intellectuals who were thirty to forty years older than me was, I can assure you, very far from embodying any form of authority, as a therapist would. In fact, my graduate school readings and the influence of poststructuralist and postcolonial thought on the US academy were matters of discussion and at times heated contestation by some of my male interlocutors, whose overall demeanor and argumentative modes of dialogical engagement manifested masculinist traits associated with an older generation of leftist militant intellectuals:

Why read so much Michel Foucault in graduate school? You were so interested in the work of Pierre Bourdieu in Beirut . . . What made you gravitate toward Talal Asad in New York? . . . I am not sure whether these are the most appropriate questions to ask . . . There is way too much pomo-poco [a mocking diminutive of postmodern and postcolonial] over there!

Edward Said was not spared. I found myself in a post-postcolonial moment during which Said’s work and its subsequent influence on postcolonial scholarship were called into question. While I was navigating these metaconversations about how conversations ought to be framed and which questions were the most pertinent to ask and about why some theories are more felicitous than others, I was at times put on the defensive as a representative of that authoritative, yet parochial, entity called “The American Academy.”

Regardless of my different interlocutors’ takes and whether I was addressed as a representative of something or not, what I was quickly witnessing was not only the contestation of authoritative theoretical paradigms but also, and perhaps more importantly, the melting of the distinction between the frames of inquiry and their objects. This increased the vertigo caused by the (always) troubled relationship between past and present, which was already exacerbated by the fact that my interlocutors were also the main historians and social scientists of the times I was interested in examining. There was no escape from engaging my interlocutors’ work if I wanted to reconstruct the historical context necessary for my own. To the acuity of the vertigo caused by the troubled relationship between past and present, text and context, source for analysis and object of analysis, was now added the melting of the distinction between theory and evidence.{16}

****

[MERIP’s special double issue in the fall of 1982, covering the Israeli invasion of Lebanon earlier that summer. Cover by Palestinian artist Kamal Boullata.]

[MERIP’s issue in the last year of the Lebanese civil and regional wars (1975–90), which includes contributions by distinguished Lebanese intellectuals, including historian Ahmad Beydoun (1942–) and social scientist/historian Fawwaz Traboulsi (1941–), who were both key figures in Socialist Lebanon in the mid-1960s and indispensable interlocutors for my own work.]

IV.

These at times heated exchanges about questions of theory and the reading practices of metropolitan postcolonial critics slowly revealed to me the paradoxical process by which the authority of the Euro-American academic center can be reinscribed in practice by the very works that contest this authority in theory, whether by deconstructing it, provincializing it, or decolonizing it. In a vivid illustration of the authority of metropolitan critical-theoretical discourses, anthropologist James Ferguson quips that “South Africans responded to the 1990s academic critiques of modernism and enlightenment with the dismayed objection: ‘You all are ready to abandon it before we’ve even gotten to try it!’”{17}

To engage the question of theory from the margins, I learned, entails the willingness to listen to criticism of the metropolitan centers’ authoritative academic theories even when these theories are critical of the West. It became clearer to me, as the South African story related by Ferguson shows us, that instead of reproducing a sense of theoretical backwardness, where thinkers in the Global South ought to catch up with the latest critical theory despite its distance from their own reality, it is more fruitful to adopt a reflexive attitude that turns the gaze inward, away from the answers theories provide and toward an interrogation of the questions they set out to ask. Whose questions are these? What is at stake in answering them? And for whom? Who gets hailed as worthy of understanding in these theories? Who is neglected? And who is critically condemned? How is difference figured? And what understandings of power undergird these theories? And, to go back to a question I broached earlier, who is worthy of the caring labors of reconstruction? And who is targeted to be undermined? These reflexive questions stand as a salutary antidote to the seldom acknowledged seductive powers of recent critical theories that practice a progressive historicism—by overcoming the blind spots of earlier theories—while critiquing (theoretically) the notion of progress. This kind of reflexive move remains valuable even though—or perhaps especially because—we have known for a while that academics, as Talal Asad puts it, “learn not merely to use a scholarly language, but to fear it, to admire it, to be captivated by it.”{18}

****

V.

My long and frequent meetings with my interlocutors were permeated by a tension between, on the one hand, the need to relax my political and intellectual disagreements to enable a deep listening in order to disclose the worlds I was drawn to, and on the other, my desire to defend my own, at times generational, preoccupations. This was a tension between the ethnographic disposition of docility—of letting yourself be taught something like a child, and guided by the hand to a new world like a recent convert—and the agonistic dimension of intellectual and political dialogue, the resistance to having one’s world constituted by the other’s narrative.{19} I had to accommodate myself to that space constituted by the unresolved tension between docility and resistance.

To be only a docile subject was akin to personal and generational submission, to relinquishing my own experiential vantage point and my own questions in order to see the world through their eyes. It would have been a classic case of the inheritor being inherited by the inheritance.{20} On the other hand, to be completely refractory to their own voices and suspicious of all their claims would be to foreclose my partial access to their worlds, leaving me much poorer for it. It would be a case of refusing to establish any relation between their past and my present. A severance of inheritance. How to negotiate one’s relationship to the past, to one’s inheritance, between complete identification and unequivocal severance? How to listen deeply, closely, generously without converting?

When I returned to New York, I read Susan Harding’s refined ethnography of American fundamentalist Christianity.{21} Her evocative analysis of the rites and rhetorics of conversion resonated deeply with some of my experiences with male Arab Marxist intellectuals. Harding points out the dangers of engaging in the kind of research where the conjunction of the closeness between interlocutors—as in the cases of inhabiting a shared tradition—and the necessity of listening to enable the work of ethnography makes you susceptible to the contagion of language. It opens you up for narrative encapsulation, as Harding notes.{22} For her, the principle of conversion, which resides in one person insinuating his or her mode of interpretation in the mind of another, informs all dialogue.{23}

Despite the many ideological differences between American Christian fundamentalists and disenchanted Arab Marxists, I could detect structural similarities in the dynamics of the encounter. For one, the asymmetry of power at the moment of encounter between those seeking to understand and those to be understood, which is often highlighted, and rightly so, was not entirely on the former’s side, our side. In fact, in Harding’s case as well as mine there was a reversal of roles.{24} We, the listeners in search of understanding the other, were the ones being questioned and mapped by our interlocutors, at times in order to be converted. This peculiar situation, in which the mapper was being mapped while insisting on not relinquishing their task, at times pushed my dialogical encounters into agonistic terrain. Here I found myself on the defensive, as battles for narrative encapsulation were engaged by my interlocutors, along theoretical and political lines, about how to reconstruct the histories of the Left and Lebanon in the past few decades.

Understanding turned out to be a much more complicated affair than I had first envisaged. In fact, Spinoza’s famous adage—“I have striven not to laugh at human actions, not to weep at them, nor to hate them, but to understand them”—which Pierre Bourdieu was fond of citing, seemed to cover only half the equation.{25} For it is an injunction directed toward the I, which it takes to be a composed, stable, and self-possessed I that faces a world in need of understanding and interlocutors who do not know, as the I does, the principles behind their apparent domination. At least that’s how I understood it. What it does not take into consideration is how the I itself is partially at stake in these dialogical encounters. How in certain situations, such as the ones Harding went through, the encounter may veer in the direction of refashioning the I by emptying it of its past life before proceeding to recast it in an alternative idiom.{26} In short, understanding becomes entangled with insinuation, suggestion, argumentation, and conversion.{27} The more you lend your ear, the more vulnerable you become and the more you risk ending up disoriented. All these entanglements exacerbated the vertigo I was suffering from.

****

VI.

The ends of a conversation, I learned with time, looked different depending on which side you viewed them from. In my double role as intergenerational interlocutor and researcher, I was a relay of sorts, aspiring to rescue theoretical, political, and generational pasts from oblivion. I was not, however, broadcasting the same signal I was receiving. It first had to be processed, since I also wanted to understand the travails of this generation of militant intellectuals that occupied mythic proportions in my imaginary as I came of political age in mid-1990s Beirut. In looking back I hoped in part to work through my own personal-generational cathexis on the 1960s Left. I also strove toward a more lucid understanding of the times of war we grew up in and their relations to the postwar period.

[The murderer returning to the scene of the crime (2013), a digital collage by Syrian video collective Abounaddara. The collage appropriates the original work of French painter André Dutertre, Souleyman el-Halebi: Assassin de Kléber (1836), by adding a Kalashnikov and a beanie hat made out of the flag of the Syrian revolution.]

As I grew older, while I was reworking my dissertation into a book manuscript, I began looking forward as well, seeing that perhaps the narration of the political vicissitudes of the 1960s generation, that revisiting their anabasis, might be valuable to those younger than me—those generations who came of age during the successive Arab revolutions (2011–) and had the luck and misfortune of being drawn in, and swept away, by the waves of the event.{28} I listened in search of self-clarification and with hopes to relay. To borrow a distilled sentence from David Scott, I listened “not as a matter of nostalgia, but as a matter of cultivating and sustaining a tradition of public memory.”{29} From my interlocutors’ perspective, I was the addressee of their speech. The final destination of their discourses. They addressed me personally, as someone from a younger generation who did not live through their times but was interested in their lives and works.

They too displayed symptoms of resistance. Initially, these resistances cropped up during our conversations. Later on they manifested in reactions to some of my written work or presentations of it in their presence. Their resistances, of course, were not related to modes of conversion that insinuate themselves in extended and detailed dialogues over the years. At times they were reactions to what could be construed from their end as my attempts at objectification or reification, as when I’d say something like, “So that’s what you thought back then!” They also resisted, and rightly so, being framed by the hegemonic paradigms of the US academy. In this case, that mode of narrative encapsulation would have taken the form of elevating Said’s Orientalism and subsequent postcolonial critiques to the high skies of theory, which would then frame my interlocutors’ works, reducing them in the process to shadows of Western thinkers: unoriginal, Western-influenced, local intellectuals. Last but not least, since we are talking about influential intellectuals who were at times comrades in the same political organization before going their separate ways personally, politically, and intellectually, they also resisted one another’s differing interpretations of their shared past.

For the sociologically inclined, these multiple modes of resistance might call to mind an observation by Zygmunt Bauman that Claudio Lomnitz and Dominic Boyer flesh out in a helpful essay on intellectuals and nationalism. They write,

The thing about writing on intellectuals is that every representation is bound to be, to some extent, a self-representation. Any move to produce definitive knowledge of intellectual works and lives must be measured against the certainty that this knowledge is also a product of a situated, motivated, gendered intellectual whose writing reflects a specific time, place, and position in intellectual culture. In what Bauman views as a postmodern condition par excellence, the chief certainty of a social analyst of intellectuals becomes the relationality of his/her own interpretive knowledge and of the knowledges produced by his/her subjects.{30}

Lomnitz and Boyer’s words were very helpful in underscoring the necessary reflexive character of my work on and with intellectuals. Having said that, it was less the question of producing definitive knowledge that I was struggling with than the question of how one goes about reconstructing the lives and works of contemporary intellectuals, who like all of us are prone to the reorientations of the living. I found intellectual sustenance in that regard in Talal Asad’s concluding words to “The Idea of an Anthropology of Islam,” his paradigm-shifting essay:

To write about a tradition is to be in a certain narrative relation to it, a relation that will vary according to whether one supports or opposes the tradition, or regards it as morally neutral. The coherence that each party finds, or fails to find, in that tradition will depend on their particular historical position. In other words, there clearly is not, nor can there be, such a thing as a universally acceptable account of a living tradition. Any representation of tradition is contestable. What shape that contestation takes, if it occurs, will be determined not only by the powers and knowledges each side deploys, but by the collective life they aspire to—or to whose survival they are quite indifferent. Moral neutrality, here as always, is no guarantee of political innocence.{31}

While Asad shares Lomnitz and Boyer’s preoccupations with questions of situatedness and the contestability of representations, his words about the narrative relation one inhabits to a living tradition resonated deeply with what I was trying to do as an intergenerational interlocutor doubling as anthropologist. Asad points to a dimension of the reconstructive labors of writing that is thicker than the reflexive sociological mapping of situatedness in terms of the categories of gender, class, race, generation, and so on. His words underscore that situatedness translated into representation is also enmeshed in existential wagers about the kinds of attachment we have to a tradition (or not) and our degrees of implication in it at the time of writing.

****

VII.

Navigating the sinuous paths of the dialogical terrain—disorientation, understanding, insinuation, suggestion, conversion, resistance, contestation—was further complicated by the fact that all of us knew, as I listened to them over many years and for long hours, that there would come a time when I would sit down and write something. Inscription, objectification, translation, and synthesis would all come from my side. I was in the process of weaving a narrative about a generation of militant intellectuals out of many singular trajectories, theoretically different works, and divergent party experiences. Moreover, I would be doing it not in Arabic but in English, and in a powerful and authoritative Euro-American academic field.

Our face-to-face dialogues conducted in Arabic were permeated by their authority—more accurately, by multiple variations on the mode of masculine authority peculiar to a generation of leftist militant intellectuals. They were, for the most part and to different degrees, in control of their narratives. For example, the late Muhsin Ibrahim (1935–2020), secretary-general of the Organization of Communist Action in Lebanon for around half a century, whose demeanor, manner of speaking, and overall poise came as close as possible to those of a godfather of the Lebanese New Left, drew on omniscient, watertight narrative devices to performatively fix our respective positions in the dialogue we were undertaking: him as a narrator in control of the past and its interpretation, me as a listener-learner. It is difficult to forget his opening words about the New Left and the authority with which he delivered them:

I am going to give it to you from the beginning. There is no New Left in Lebanon without a previous political foundation. Nothing fell on us called the New Left. The issue wasn’t that the Lebanese students observed the French students’ revolution [May 1968] and decided to do something similar.{32}

But Ibrahim, the seasoned politician who at one point was close to President Nasser before breaking with Arab nationalism to adopt Marxism, was the outlier in a group of militant intellectuals. In fact, paradoxically enough, the patriarchal transcendental position he occupied during our meeting did not leave any room for the kind of dialogue outlined above with the usual rhetoric of insinuation, suggestion, and conversion. His distant omniscience laid things before me as they were, and he had no interest in getting closer to win me over to his side. For the most part, I asked a lot of questions and listened even more, and every now and then I pushed back, mainly in reaction to what I construed to be manifestations of paternalistic masculinity.

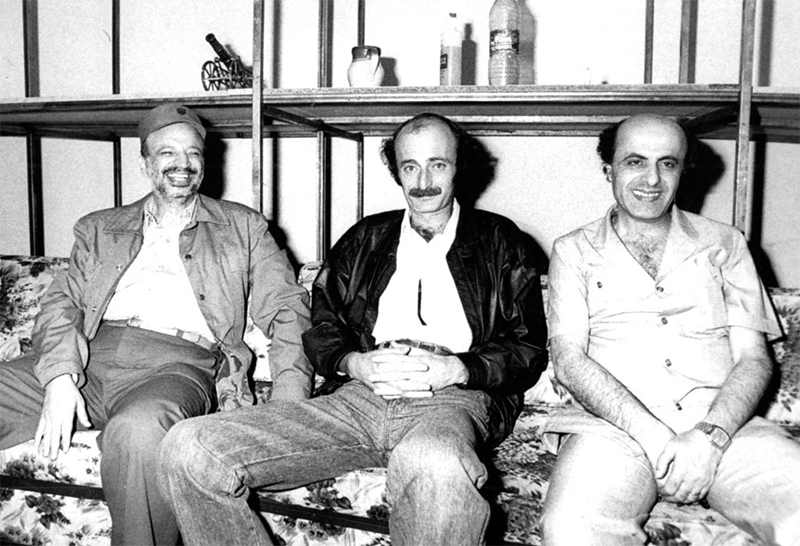

Muhsin Ibrahim (far right) with the Palestine Liberation Organization leader Yasser Arafat (far left).

Muhsin Ibrahim (far right) with the Palestine Liberation Organization leader Yasser Arafat (far left).

****

Coda

Back in New York, things were different. I was alone with hours of interview recordings and folders of xeroxed political party archives and out-of-print materials. Listening in boisterous Beiruti coffee shops—which later left me tinkering with my audio devices to lower the cacophonous background noise and pick up a missed word from an interviewee—would now morph into slow, solitary writing in the freezing-in-the-summer and overheated-in-the-winter US university libraries. But to kick-start the writing I had to go back and listen to my interviews. I was no longer the addressee of a voice sitting right across the table from me. I was listening alone to a recording of two voices, my interlocutor’s and mine, separated from the original encounter by time and space.

This mode of listening, besides the mixture of uncanniness and cringe it produces as one experiences one’s own recorded voice as a familiar “other,” is a metalistening of sorts. This second-order listening—listening to oneself now listening then—triggers its own vertigo due to the dizzying amount of information one’s ears soak in from recordings. I found myself having to focus much harder than I had to when conducting the in situ interviews to maintain a distinction between our foreground—our conversation—and background—the sounds coming from the street, the chatter of people sitting at tables next to us, waiters and baristas taking orders, cars passing by, waves breaking on the shore. My first runs of listening, which could include repeated rounds of the same recordings, were immersive practices. I was not listening for something in particular. Rather, I sought through listening to dwell in the worlds and words of my interlocutors. This immersive mode of listening, most times with headphones on, accompanied my everyday activities: listening-walking, listening-jogging, listening on the subway.

Seeing the narration of the 1960s generation, revisiting their anabasis, might be valuable to those who came of age during the successive Arab revolutions (2011–) and had the luck and misfortune of being drawn in, and swept away, by the waves of the event.

This mode of listening was contrapuntal to the practice of live dialogical listening. Instead of filtering the surrounding sounds out and engaging the one voice sitting across from me, I was now simultaneously listening to at least two voices engulfed in many different sounds. This listening at a spatiotemporal remove comes with its own seductive temptations, which chip away at the focus deep immersion requires. Primary among these was the capacity of recordings of voices in dialogue and the soundscapes surrounding them to transport the listener momentarily to a whole way of life one misses, to render acoustically present worlds which partook in shaping one’s sensibility and that were once, a long time ago, inhabited unreflexively. And with that comes the likelihood of triggering involuntary memories, like Marcel Proust’s experiences but this time set off by sound. Recorded soundscapes have the power to disclose lost worlds nested in the texture of a voice. Worlds brought back by the click of a cigarette lighter.

[Still frame from The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi and 27 Years without Images (Éric Baudelaire, 2011) depicting Hamra Street in Ras Beirut.]

Having reckoned with all these temptations, I could start listening for the arc of the conversation, its silences, hesitations, ill-formulated questions, lamented interruptions, pitches, digressions, conversational volte-faces, argumentative crescendos, and rambling answers. Only then, and after repeated listening, would I begin jotting down preliminary ideas, with one ear tuned to my interlocutors’ words in Beirut and the other to a different set of authoritative conversations taking place in the Euro-American academy.

Early in the process, it became clear to me that to repress the reasons behind my vertigo would not be a sensible, or even sane, thing to do. So I decided to make a virtue out of necessity, another thing I learned from Bourdieu, by attempting to write about the multiple troubled boundaries I was experiencing—between text and context, sources for analysis and sources of analysis, theory and evidence, past and present, frames and data, peers and objects of analysis, concepts and narrative, foreground and background. In doing so, I wrote to address the causes of my vertigo.

In the first stages, I told myself I wanted to write something that could be read in both New York and Beirut, knowing very well the different stakes animating them as problem-spaces and the structural economic, institutional, and linguistic inequality separating them. I’m not sure I succeeded in doing so. After all, the book’s critical intervention is slanted toward Euro-American theoretical and disciplinary debates. Would it have been better to write two different books—one in English and another in Arabic—offering different things to different audiences, two books working their way through the different sets of attachments one develops as a result of inhabiting multiple spaces? I’m not sure of this either. It would forego the stakes involved in the practice of translation. What’s more, it could foreclose the possibilities of emergence, and of newness, since friction, as Anna Tsing has argued, “reminds us that heterogeneous and unequal encounters can lead to new arrangements of culture and power.”{33}

For me, writing worked to alleviate the vertigo of listening. But only for a while. After the writing was done and, more importantly, after it was congealed in book form, the vertigo returned. This time around, it was precipitated by the arduous process of translating the writing back into Arabic.

I am grateful to Alireza Doostdar, who read and commented on an earlier draft.

Title video: The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi and 27 Years without Images (Éric Baudelaire, 2011)

{1} Louis Althusser and Étienne Balibar, Reading Capital, trans. Ben Brewster (London: Verso, 1979), 16n1.

{2} See Stefan Tarnowski, “What have we been watching? What have we been watching?,” Bidayyat, May 5, 2017.

{3} David Scott, Stuart Hall’s Voice: Intimations of an Ethics of Receptive Generosity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 36.

{4} On the relation of secular criticism to heroism, see Talal Asad, “Historical notes on the idea of secular criticism,” The Immanent Frame, January 25, 2008.

{5} See Ghassan Hage, “Eavesdropping on Bourdieu’s Philosophers,” Thesis Eleven 114, no. 1 (2013): 76–93.

{6} Edward W. Said, afterword to Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1994), 336.

{7} Said, Orientalism, 336.

{8} See Leila Ahmed, A Border Passage: From Cairo to America—A Woman’s Journey (New York: Penguin Books, 2012).

{9} Said, Orientalism, 8.

{10} Talal Asad, review of Orientalism, by Edward Said, The English Historical Review 95, no. 376 (July 1980): 648.

{11} Tarek El-Ariss, Leaks, Hacks, and Scandals: Arab Culture in the Digital Age (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019), 3.

{12} El-Ariss, Leaks, Hacks, and Scandals, 178.

{13} I refer here to Edward Said’s earlier book Beginnings: Intention and Method (New York: Basic Books, 1975).

{14} Fadi A. Bardawil, Revolution and Disenchantment: Arab Marxism and the Binds of Emancipation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020).

{15} Christopher Bollas, Meaning and Melancholia: Life in the Age of Bewilderment (New York: Routledge, 2018), 81.

{16} See Brinkley Messick, The Calligraphic State: Textual Domination and History in a Muslim Society (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 5.

{17} James Ferguson, “Theory from the Comaroffs, or How to Know the World Up, Down, Backwards and Forwards,” from the series “Theory from the South,” Cultural Anthropology, February 25, 2012.

{18} Talal Asad, “The Concept of Cultural Translation in British Social Anthropology,” in Writing Culture, ed. James Clifford and George E. Marcus (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 164.

{19} “The disciplined body,” Talal Asad writes, “is not a coerced body but a ‘docile’ body, in the older sense of a body that is ‘teachable.’ To be teachable is not only to be able to listen to another person (one’s teacher) but also and especially to be able to listen to oneself; that is a skill to be acquired and perfected through tradition.” Talal Asad, “Thinking about Tradition, Religion, and Politics in Egypt Today,” Critical Inquiry 42, no. 1 (2015): 176.

{20} Pierre Bourdieu, “The Contradictions of Inheritance,” in Pierre Bourdieu et al., The Weight of the World: Social Suffering in Contemporary Society, trans. Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson, Susan Emanuel, Joe Johnson, and Shoggy T. Waryn (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999), 508.

{21} Susan Friend Harding, The Book of Jerry Falwell: Fundamentalist Language and Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000).

{22} Harding, Book of Jerry Falwell, 65.

{23} Harding, 37.

{24} Harding, 40.

{25} Baruch Spinoza, Tractatus Politicus [1677], ch. 1, sec. 4; a version of this quote can be found in Bourdieu et al., Weight of the World, 1.

{26} Harding, Book of Jerry Falwell, 40.

{27} See Fadi A. Bardawil, “The Solitary Analyst of Doxas: An Interview with Talal Asad,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 36, no. 1 (2016): 152–73.

{28} On anabasis, see Alain Badiou, Le Siècle (Paris: Le Seuil, 2005); the film The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi and 27 Years Without Images (2011), directed by Éric Baudelaire; and Naeem Mohaiemen, “All That Is Certain Vanishes into Air: Tracing the Anabasis of the Japanese Red Army,” e-flux Journal, no. 63, March 2015.

{29} David Scott, “The Dialectic of Defeat: An Interview with Rupert Lewis,” Small Axe 5, no. 2 (2001): 87.

{30} Dominic Boyer and Claudio Lomnitz, “Intellectuals and Nationalism: Anthropological Engagements,” Annual Review of Anthropology 34 (2005): 106.

{31} Talal Asad, “The Idea of an Anthropology of Islam,” Qui Parle 17, no. 2 (Spring/Summer 2009): 24; originally published in the Occasional Paper Series, Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, Georgetown University, 1986.

{32} Muhsin Ibrahim, interview by author, Beirut, August 4, 2008.

{33} Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 5.