Working with Visual Remains

Azza El-Hassan

In 2017, I began asking questions about visual remains: Can photographs and films that have survived Israeli plunder be used by Palestinian filmmakers, like any other found footage? Or does the violence of plundering change the nature of such images and leave us unable, as a society and as filmmakers, to relate to our own visual culture?

My search for these remains became The Void Project, a multimedia art project that uses photos and films which have survived a plundering event in order to understand the present nature of these images today, after the violence. In The Void Project, images that have survived are restored, gazed at, and integrated into new narratives.{1} In this essay, I look at the restoration portion of The Void Project’s work, tracing films that are now visual remains through the process of restoration and release back to the public.

To find photos and films that had survived plunder, in the absence of a physical space where Palestinians might accumulate images and watch them together without the constant threat of invasion or elimination, I turned to the virtual world. Online, I hoped to connect with salvagers—individuals who had retained or rescued an image from looting or destruction. Through this virtual search, I eventually connected with two women filmmakers, Layaly Badr and Arab Lotfi. Both of them had worked at the Palestinian Cinema Institution (PCI), which was plundered in 1982 during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. Both had held on to copies of films they produced for the plundered institute. The Road to Palestine (1985), an animated short directed by Layaly Badr, was a coproduction between the PCI and the GDR (former East Germany). At that time, PCI members were thinking of introducing animation into their productions but lacked the know-how, so a decision was made to send Badr to the GDR to learn how to make animated films. When Israeli forces pillaged Lebanon, Badr was still in East Germany editing her film. By the time she finished, the PCI had been looted and destroyed. She was unable to deposit her 16mm film in the archive that was supposed to maintain and preserve it. As Badr moved from one exile to another, her film print moved with her, until she finally settled in Egypt, where she kept it in her home.

Arab Lotfi’s The Upper Gate (1991), by contrast, was made after the destruction of the PCI. As the filmmaker explained to me, the point was “to insist that although the institute was attacked and robbed, we were still able to produce films.”{2} Financed by the PLO, which after being forced out of Lebanon was now based in Tunisia, The Upper Gate was one of the last films to be made after the destruction of the institute and before production completely halted a few years later. In different ways, Badr’s and Lotfi’s films struck me as perfect visual remains of plundering, both rife with images I could explore in my own visual narratives.

I located another two films not online but in the attic of my next-door neighbor in Amman. Palestine in the Eye (1976) was produced and directed by PCI filmmakers to commemorate the life and achievements of Hani Jawherieh—a cofounder of the institute’s predecessor, the Palestine Film Unit (PFU), and its lead cinematographer—after he was killed in a shelling while filming in the Lebanese mountains. Jerusalem, Flower of All Cities (1969), Jawherieh’s portrait of his home city (set to the Fairuz song from which it takes its title), was shot prior to his joining the PLO. Almost all of Jawherieh’s work was plundered in 1982, with the exception of a few visual remains that his wife, Hind, salvaged prior to Israel’s attack and before she fled Lebanon for Jordan. Unable to carry all of her husband’s work to her new place of exile, Hind took only what she deemed important enough. Her selection determined what traces of Jawherieh’s work remain in Palestinian spheres today.

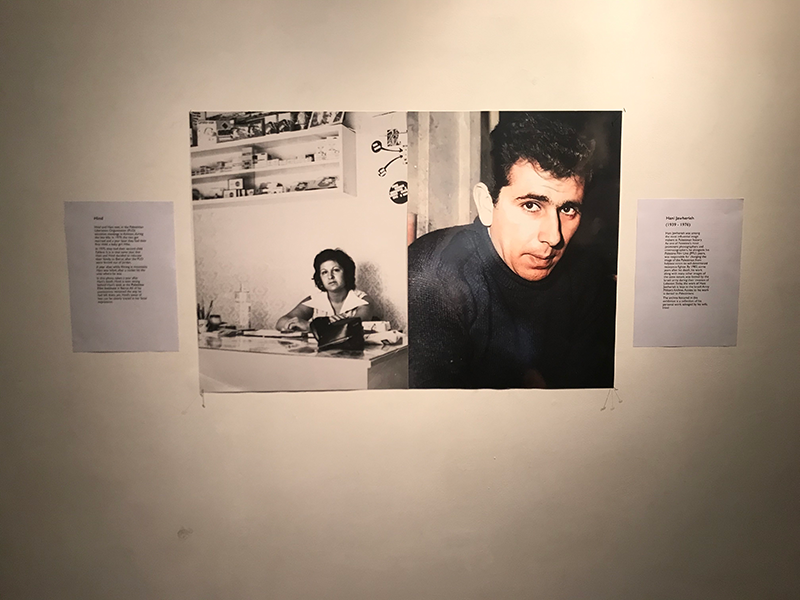

Artists’ corner, Hind & Hani Jawherieh. From the 2019 exhibition THE FOUND ARCHIVE OF HANI JAWHERIEH, P21 Gallery, London.

Artists’ corner, Hind & Hani Jawherieh. From the 2019 exhibition THE FOUND ARCHIVE OF HANI JAWHERIEH, P21 Gallery, London.

Through the years, Hind improvised methods of preserving the images she salvaged; her decisions, of course, affected the condition of the images and film reels. To some, Hind might appear to be an archivist more than a salvager, since she acted like archivists who “continually reshape, reinterpret, and reinvent” the items in their care.{3} But salvagers are not archivists and should not be defined as such. As a salvager, Hind challenged siege, crossed borders, and maintained the films on her own, without the resources of an archival institution to relieve her of this enormous responsibility. What motivated her had nothing to do with reshaping or reinterpreting. She was driven only by the desire to preserve what belonged to her husband.

To me, Hind is more of an artist than an archivist. When I staged a 2019 exhibition of visual remains of plundering, I displayed Hind’s picture in an “artists’ corner” alongside that of her husband, Hani.{4} The visual remains on display had been created and influenced by not one but two artists.

****

In order to perceive the marks a film acquires as the visual remains of plundering, after the film has been separated from an institution designed to preserve it and obtained by an individual, usually its salvager, I needed to examine its individual frames. Film restoration, a process that entails breaking a film apart and tending to each frame in it, was the method I chose to achieve this. I was seeking to perform a kind of restoration that attended not only to what Janna Jones calls the first chapter in a film’s life, but also to what she describes as a film’s various elements and layers that shape it into what it is today.{5} Such a restoration was meant to aid in revealing the afterlives of these four films—The Road to Palestine, The Upper Gate, Palestine in the Eye, and Jerusalem, Flower of All Cities—following the plundering of the PCI in 1982.

Away from temperature-controlled rooms, humidity had eaten away parts of the four films’ images, and dust had left its marks on the films’ celluloid. Their colors faded, each of the films looked much older than they actually were. Acknowledging that these marks and degradations were evidence of the violent afterlives of these films, I decided not to cleanse the films completely of them. Instead, I restored the image only when the details of it were difficult to see. For example, in one image from Palestine in the Eye, prior to restoration three figures ringing a bell could hardly be seen, especially when the image was in motion; restoration made them more visible. Elsewhere in the film, vertical scratch lines were left in place when they were sparse, but eliminated at higher frequencies.

In Palestine in the Eye, one section was so badly damaged by humidity that the image was no longer present. This part of the film therefore needed to be edited out. It was a painful decision to make considering that the process of restoration was intended to salvage and resurrect these images, not eliminate them. Nevertheless, the damaged part was cut out in order not to disrupt the experience of watching the film.

Before and after restoration, PALESTINE IN THE EYE (Mustafa Abu Ali, 1976).

Before and after restoration, PALESTINE IN THE EYE (Mustafa Abu Ali, 1976).

Color correction was applied to all four of the films, because the faded prints seemed to consign the films to a distant past where they didn’t belong, thus contributing to the erasure process that plundering implements. With the restoration complete, the four films looked imperfect, as they should. You could still see signs of the damage that had been inflicted on them. Yet they were also brought back from a past imposed on them and restored to the actual era in which they were produced.

****

Although my intention throughout this process was to turn these films into footage for a possible new film, it did not feel right to use their images this way before releasing the films back into the public domain. Publicly screening films that once belonged to a film archive that had been looted, concealed, and made forbidden to Palestinians was an ethical duty—failing to meet it would have turned me into an accomplice in denying Palestinian history, as it was told by its own people to Palestinians and to the rest of the world.

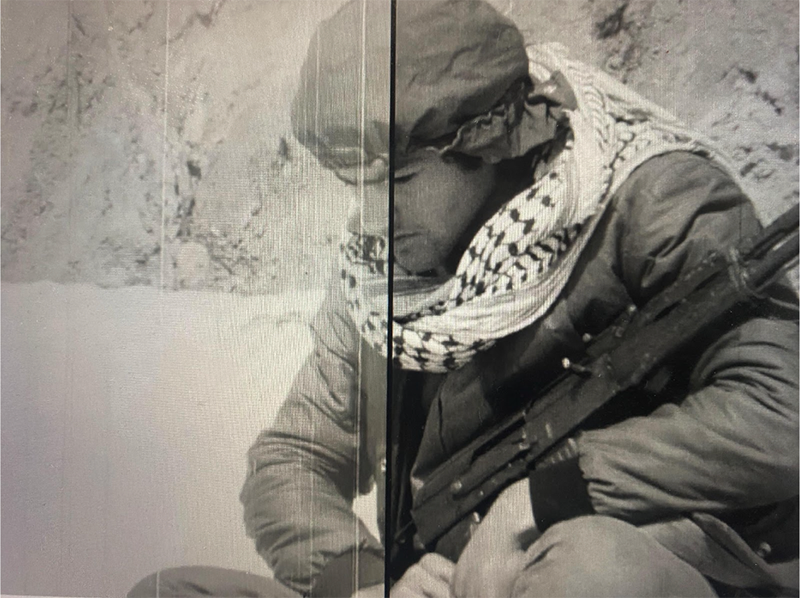

When I interviewed filmmaker Khadijah Habashneh, the PCI’s chief archivist, for my documentary Kings and Extras: Digging for a Palestinian Image (2004), she described on camera what it meant for Palestinian refugees to watch the films produced by the PCI. She spoke about the feeling of power and the sense of identity the refugee spectators experienced as they gazed at the screen where a freedom fighter, a fida’i, stood. Her description captivated me, and I suddenly felt a desire to reproduce a form of spectatorship experienced once upon a time.

The films from the revolutionary era of Palestinian cinema, in which Palestinians portrayed themselves as liberators in control of their own destiny, as Nadia Yaqub has described, were now restored and ready to be publicly screened.{6} I organized screenings in refugee camps, art centers, and cinemas in Europe, the Arab world, the Americas, and Japan. To my surprise, as each of the films played, in different settings, the plunderers seemed to appear within the narrative unfolding on the screens. It was not the physical damage on these films that recalled the plunderers and their violence, but more the knowledge on the part of the spectators that they were watching visual remains of a plundered film. Violence, the pretext from which these films emerged, was now an integral part of how the films were viewed and understood. Some spectators watched the films several times, as if each time they were resisting the erasure to which the PCI films were subjected.

Just like other spectators of these films, I wanted to watch what had been denied and concealed. I suddenly felt I could not meddle with these films, nor did I have the desire to change them—except for one sequence in Palestine in the Eye that troubled me.

****

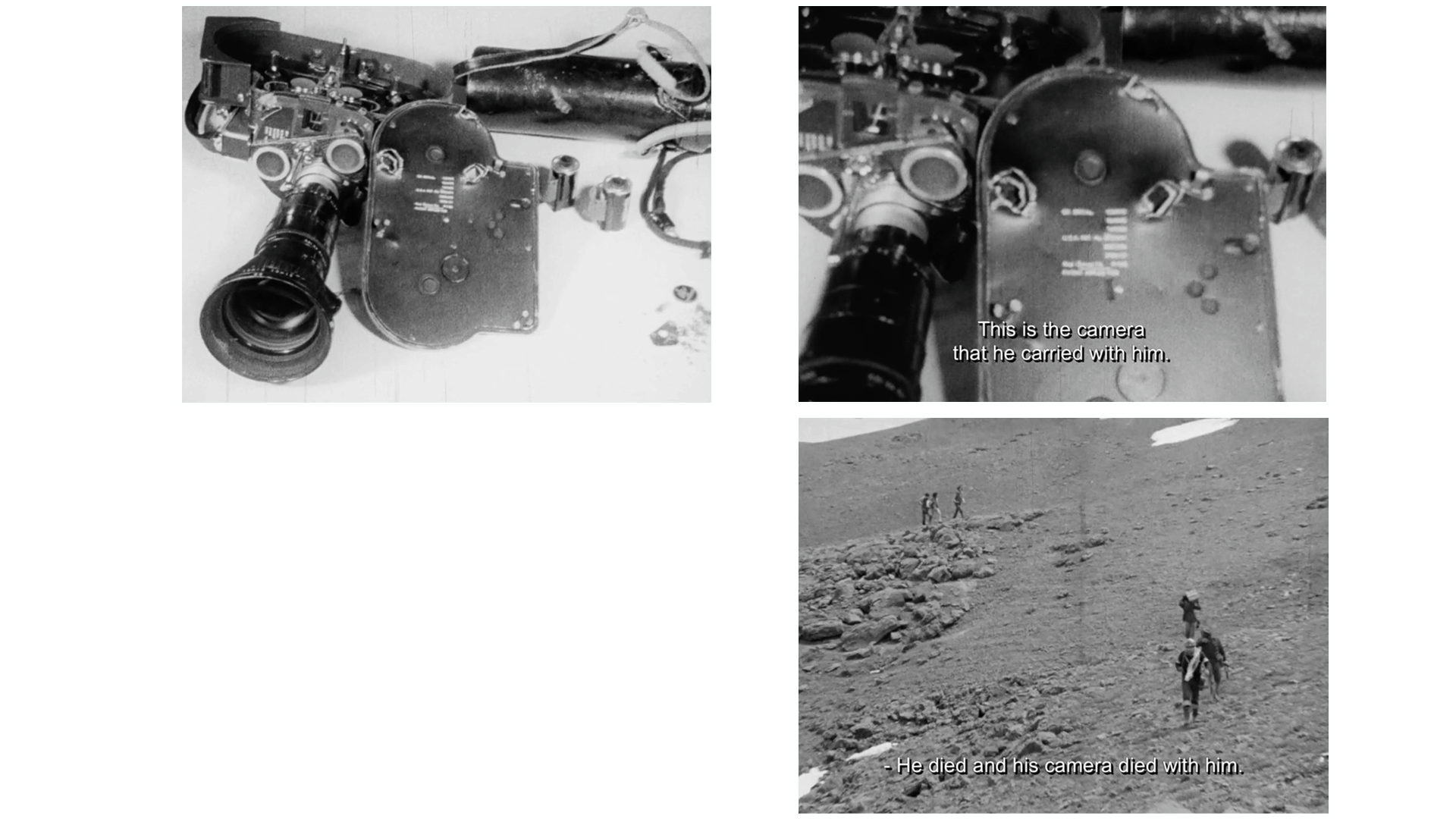

It is possible, that he filmed the moment of his death, but the film inside the camera has been destroyed. Hani became a martyr and so did his camera. The bomb that killed him killed it as well. What we are seeing now are the last five minutes he recorded prior to his death. We have put them as they are, unedited.

—Mustafa Abu Ali, filmmaker, Palestine in the Eye

A high-angle pan reveals the 16mm camera’s damaged body, which has been penetrated by a bomb’s sharp nails. Mustafa Abu Ali, one of the directors of Palestine in the Eye, informs the spectator that this camera has acquired the human property of living and dying, sharing in the cameraman’s fate.

Excerpt from PALESTINE IN THE EYE (Mustafa Abu Ali, 1976).

This is how the moment of Jawherieh’s death is depicted in Palestine in the Eye. The shots of the destroyed camera are followed by the footage that Jawherieh recorded immediately prior to his death. Presented in its entirety, this cinematic record of Jawherieh’s final moments is intended to give us a glimpse of what the prominent cinematographer saw last, before his life was terminated: a barren landscape with fighters scattered around the frame.

In Palestine in the Eye, viewers are not told anything about Jawherieh’s life prior to his becoming a militant cinematographer. Instead, the film’s narrative begins and ends on the battlefield. This condensed narrative makes what he sees in his last minutes appear, somehow, acceptable. It is as if this—Palestinian fighters in the battlefield—is what he wanted to see before he died. Yet, in relation to the striking story of a revolutionary who used his camera as a weapon, the emptiness of the frame that depicts the moment of his death seemed puzzling to me. Did the filmmakers not wish for a grander image to depict the death of one of their friends and comrades? Is this unspectacular manner of portraying death consistent with what Jawherieh himself would have wished for?

It had been more than forty years since Palestine in the Eye was made and since Jawherieh’s life was brutally cut short, and suddenly I had the urge to answer why the moment just before death recorded in Palestine in the Eye was so unspectacular—and the impulse to find a way to rectify this moment, at least on film.

****

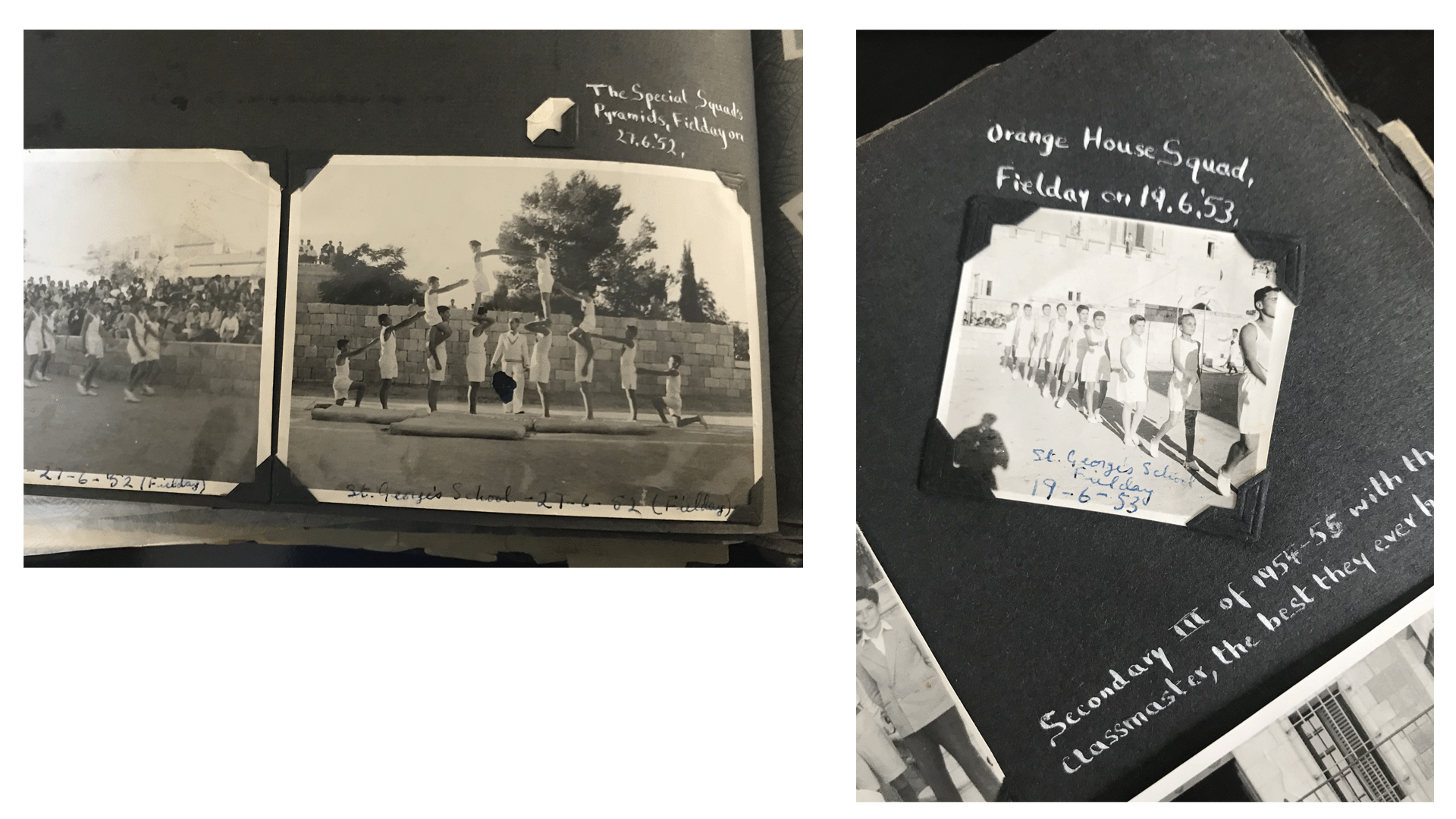

To either accept Jawherieh’s moment of death in Palestine in the Eye or to rectify it, I felt that I needed to reconstruct a narrative of his life before he became a member of the PLO and the PFU/PCI. His personal photo album, comprised of photos he took prior to 1967, seemed like a logical starting point. Jawherieh began the album in the 1950s to preserve his early images. He carried it with him when he left Jerusalem for Jordan in the early 1960s, and again when he departed for Beirut in 1975 to become a full-time photographer and cinematographer for the PLO. In 1982, Hind took the photo album with her, together with Palestine in the Eye and Jerusalem, Flower of All Cities, as she fled Beirut for Amman. It is thanks to Hind that I was able to view the album in 2017.

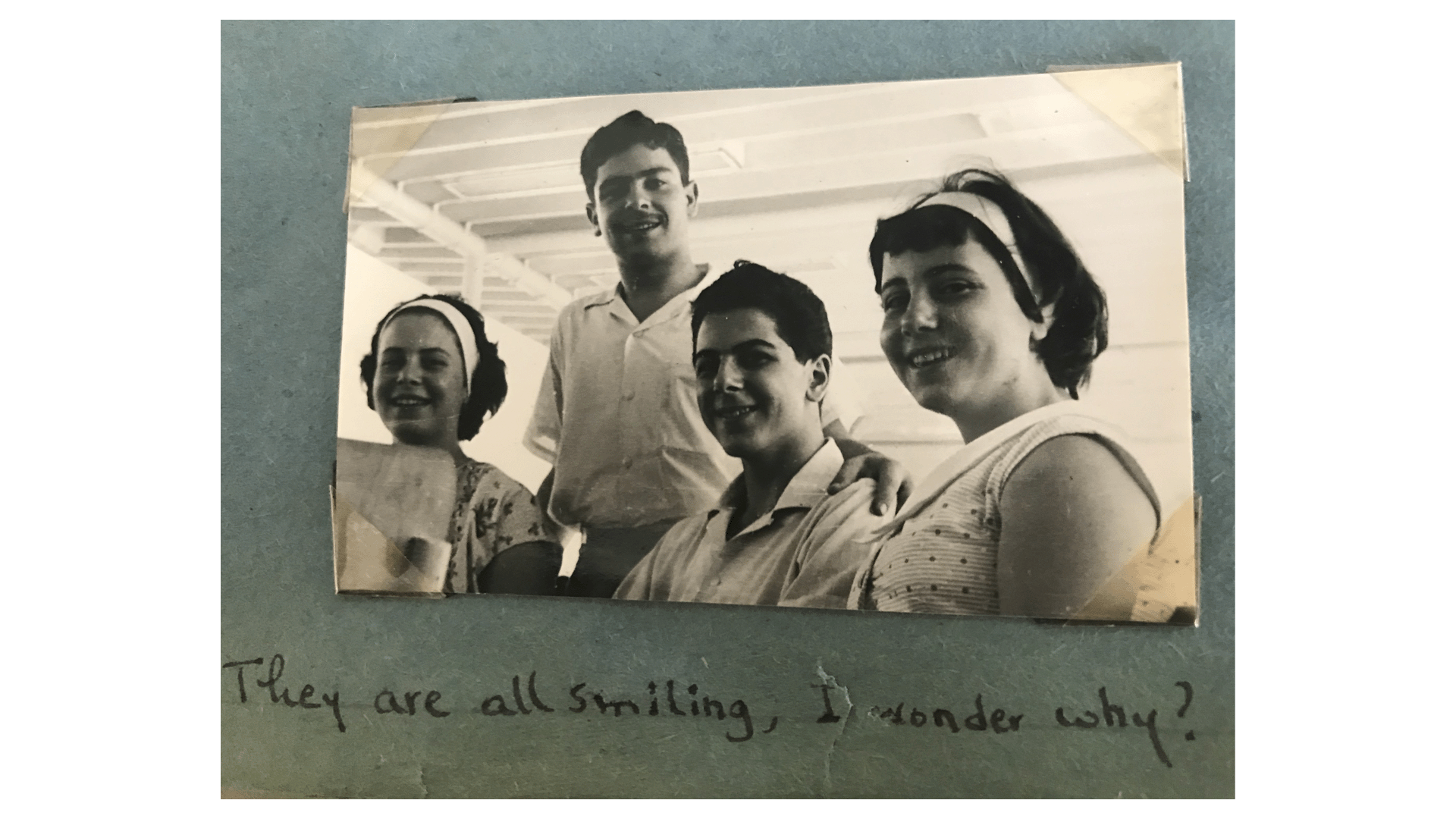

Flipping through the album pages, I could see that Jawherieh had a passion for capturing landscape and architecture. He created portraits of his native city, Jerusalem, and photographed his family and friends.

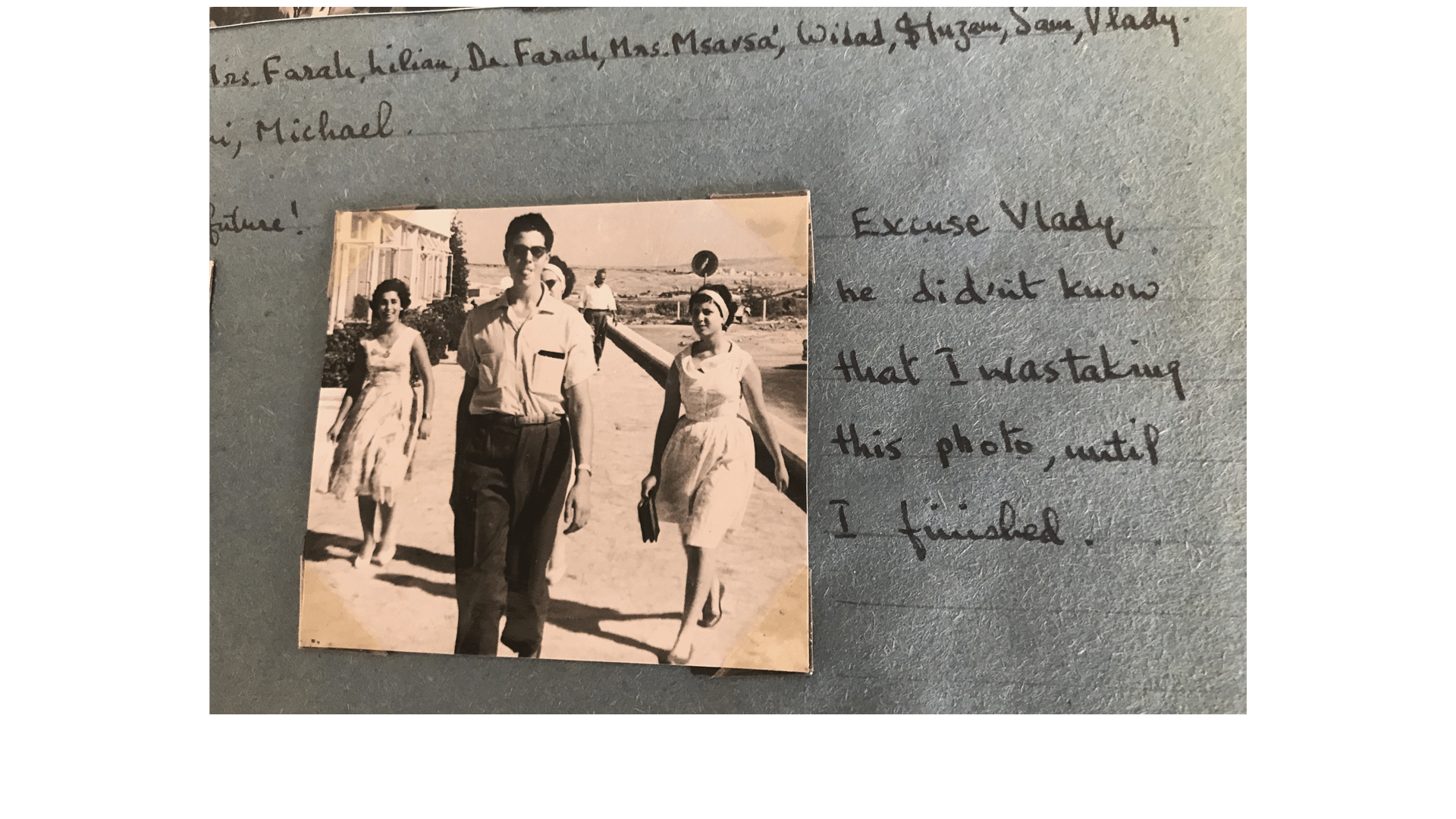

Jawherieh’s early work as a photographer can be traced in the photos he took as a student at St George’s School, where he acted as the school photographer, documenting the school’s activities and taking class photos, such as those for the graduating classes of 1952 and 1953. There are also a series of personal photos of Jawherieh and his friends, which offer a taste of their life prior to dispossession and the occupation of East Jerusalem.

The photo album offers insight into and images of the life Jawherieh led before he became the main cinematographer and photographer of the Palestinian movement during the 1960s and 70s. In his early photos, the Palestinians of East Jerusalem appear as a settled community with no inkling of the threat their world is under, no sense that the life they are living will soon cease to exist.

One young man whose photos appear repeatedly in the album is Jawherieh’s friend Vladimir Tamari. Tamari was a Palestinian visual artist who in 2016, forty years after Jawherieh was killed and a year before his own death, decided to write a short text, “Vladimir Tamari remembers his friend Hani Jawharieh.”{7} Knowing he was terminally ill with cancer, Tamari likely wrote it not only to remember Jawherieh, but also to remember his own life.

Palestine in the Eye recounts the last chapter of Jawherieh’s life, the phase in which he emerged as a revolutionary. Tamari’s text offers insight into the emotions, thoughts, and events that shaped Jawherieh’s life prior to his becoming the revolution’s cinematographer. It is the narrative that led to the transition of Jawherieh from what Tamari calls “a wonderful ordinary human being—extraordinarily ordinary,” to the “martyr of revolutionary cinema.”

In his text, Tamari, who moved to Japan in 1970, describes the moment he learned of his friend’s death: “I remember when I absorbed what happened. A grim, silent moment I remember to this day. I became very angry. I do not know why that anger turned toward those toys with which I amused myself in exile while Hani lived and died in the homeland.” Tamari’s own description of his life after leaving Jerusalem speaks to the problematic reality he found himself in. He describes his own artworks as toys, only created for entertainment purposes, and the country he has lived in for years as his exile. It is as if he was struggling to find a definition for what he had become, for what he was now doing with his life.

Tamari’s sense of deep displacement is echoed in Palestinian literature—for example, in the writing of Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, who describes himself as an accursed person walking the earth without rest, always scavenging and never reaping, “the Wandering Palestinian having replaced the Wandering Jew.”{8} Jabra evokes a world of wilderness that the dispossessed find themselves in.

I could comprehend Tamari’s sense of isolation, of being amputated from his past and unable to connect to his present. I could understand his deep sense of worthlessness. What I could not fathom was his apparent envy of Jawherieh, whose death he describes as having happened in the homeland. Tamari knew that Jawherieh did not die in Palestine, and he was almost certainly not referring to Lebanon as “home.” Like Jawherieh, Tamari was a member of the PLO, which had as its main political proposition the return of Palestinian refugees to their homeland, rather than their resettlement in the Arab world.

“Eventually they constructed an imaginative Palestinian geography,” Nadia Yaqub writes, evoking Edward Said’s description of Palestinian placemaking outside Palestine.{9} Exilic spaces such as refugee camps, as well as medical and cultural centers founded for or by Palestinians in Lebanon, Jordan, or elsewhere, were proclaimed Palestinian territories. The PLO offered such spaces, and the PCI became the imaginative geography for Palestinian filmmakers. While other liberation movements produced militant films from a home base in an established state, Palestinian cinema “operated tenuously within the PLO, vulnerable to the political exigencies that shaped the organization.”{10}

It is very possible that the homeland to which Tamari was referring was the PCI, a space where friends could meet and ideas could be shared, where an archive could be assembled, a space that stood in striking contrast with the isolation and loneliness of Tamari’s exile. Later in his text, Tamari mocks this imagined geography: “But what a farce, for I imagine how Hani, humble as he always was, would laugh long and hard at how life and history had turned out to be, how the entire nation was disinherited and insulted, yet we are proud about a street and cinema house.” The street and cinema that Tamari is referring to were in Tunisia, where a street and a cinema hall were named after Jawherieh in the wake of his killing.

Tamari’s anger offers an unexpected insight into the narrative about Jawherieh in Palestine in the Eye. After Tamari and Jawherieh lost their entire world in Jerusalem, Tamari struggled with the loss, while Jawherieh, somehow, experienced a rebirth by joining the PCI. Palestine in the Eye does not depict Jawherieh’s life prior to his becoming a militant photographer, because that happened before Jawherieh evolved from a refugee into a fighter, as members of the PCI regarded themselves.

The depiction of the last moments in Jawherieh’s life in Palestine in the Eye, through his camera and the Palestinian fighters it recorded, conveys the dominant theme of Jawherieh’s work as he became a member of the PCI. In other words, these final moments show what members of the institute and the directors of Palestine in the Eye believed Jawherieh would want to see and would want us to see: Palestinian fighters in the struggle for liberation.

****

What started as a desire to rectify a cinematic moment led me to a story of displacement and a constant search for home. It is a search with variations that can be seen in the distinct life paths that Tamari and Jawherieh took. Home was never to be found again for Tamari, while Jawherieh resided in a newly formed space, that of the PCI.

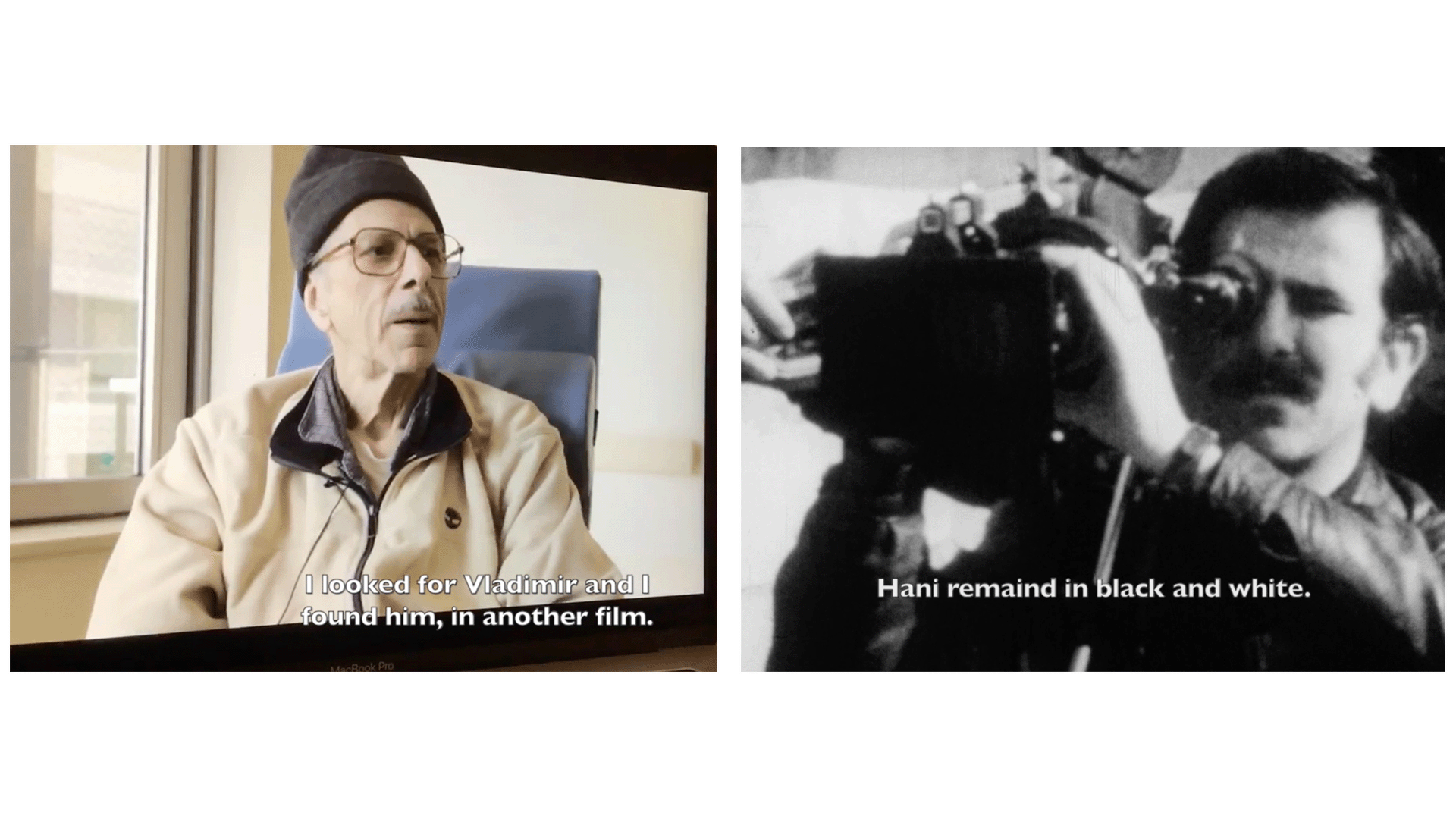

My desire to rectify was now replaced by the urge to retell the story of Jawherieh. That is, I wanted to keep Palestine in the Eye intact, while opening another space to tell Jawherieh’s narrative forty-three years after his death from the point of view of the present, as I looked at his past. In my short video essay about Jawherieh, Remake of a Revolutionary Film (2019), the narrative begins prior to loss, at a moment when Jawherieh and Tamari still thought that a homeland, a place where friendships like theirs might flourish, could be taken for granted.

REMAKE OF A REVOLUTIONARY FILM (Azza El-Hassan, 2019). Courtesy of the filmmaker.

As loss occurs in Remake of a Revolutionary Film, the two protagonists in the film, Jawherieh and Tamari, begin to dwell in isolated spaces. Tamari is seen in a hospital setting, which could be anywhere in the world. These shots of Tamari were taken by Mohanad Yaqubi, who filmed him in the hospital in Japan where he was being treated for cancer, in what appears to be a lonely, isolated space.{11} Meanwhile, Jawherieh appears in a dreamlike black-and-white image, dwelling in no place but the imagination of the viewer.

Jawherieh’s 16mm camera is brought into Remake of a Revolutionary Film, only this time it’s quickly stripped of the martyr role it performs in Palestine in the Eye. It appears now, in the present, transformed into an object on display.

To retell the moments prior to Jawherieh’s death, I borrow the soundtrack from Palestine in the Eye. Sounds of gunfire and shelling are superimposed on a conversation between Mustafa Abu Ali and Jean Chamoun, who inform us, the viewers, that what we see onscreen are the last images that Jawherieh saw before his death. In my film, these sounds accompany images of a different life that Jawherieh once lived, prior to becoming a revolutionary.

Title video: Remake of a Revolutionary Film (Azza El-Hassan, 2019).

{1} See: The Void Project.

{2} Arab Lotfi, telephone conversation with author, London to Egypt, 2018.

{3} Joan Schwartz and Terry Cook, “Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory,” abstract, Archival Science 2 (2002): 1.

{4} The Found Archive of Hani Jawherieh: The Art of Accessing Forbidden Art, P21 Gallery, London, curated by Azza El-Hassan, November 7–30, 2019.

{5} Janna Jones, “Film Restoration: A New Way of Seeing Film History,” in The Past Is a Moving Picture: Preserving the Twentieth Century on Film (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2012), 137–66.

{6} Nadia Yaqub, Palestinian Cinema in the Days of Revolution (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018), 7.

{7} “Vladimir Tamari remembers his friend Hani Jawharieh,” Vladimir Tamari (website), July 30, 2016.

{8} Jabra I. Jabra, “The Palestinian Exile as Writer,” Journal of Palestine Studies 8, no. 2 (Winter 1979): 77.

{9} Yaqub, Palestinian Cinema, 7.

{10} Yaqub, 2.

{11} Specifically, the images come from Mohanad Yaqubi’s Memory Portraits (2016).