Bidayyat \ Lineaments of Iltizam

Katy Montoya

In 2019, at a Q&A after a screening of Still Recording (2018) in Beirut for the Almost There festival, questions posed by an audience composed mainly of Lebanese and Syrian spectators offered a glimpse into the filmmakers’ multiple commitments on the issue of turning the Syrian revolution’s armed dimension into cinema. The Lebanese moderator asked the first question: “Art, filming, and music play a huge role [in Still Recording]. . . . What was the role of art and especially the camera in those days . . . when people were carrying weapons and a war was happening?” Ghiath Ayoub responded by citing his codirector’s reflections on filming a massacre that took place in Douma during the battle to liberate the suburb of Damascus from regime forces, one of the film’s opening scenes. Saeed al-Batal filmed because “the camera was like armor . . . it didn’t protect [us] against bombs and war, but from going mad.”{1} While the moderator subsumed the act of filming under the category of “art,” Ghiath underlined its difference. The act of filming occupied an intermediary role between painting and armed battles, both of which are depicted in the film. Filming was a way of engaging the mental and spiritual terrain of resistance and struggle, Ghiath suggested. The fact that the film’s first scene is “a course on the best practices for filming a movie, and [in what ensues in the film] all those rules are broken,” was proof not so much of the incommensurability between filming and armed struggle, but of the need to reimagine their relationship.

Other audience members focused on the film’s political implications. A Syrian man asked why there was a “clear bias” toward secular currents when, in fact, he said, secularists played only a secondary role in the revolution. When he attempted to ask a follow-up question about the Islamists in the film, the microphone was taken away from him to make room for less charged questions. The next question was also posed by a Syrian audience member, who returned to the issue of art in war: “Everyone was hungry. Why did you choose to work on art—on painting, playing music, happiness? . . . Maybe all this happiness was present, and that’s beautiful, but why is this how you depicted it?” The suggestion was that the film aestheticized war. Then the final question: “Why were weapons able to enter the siege but not food? I’m from Syria, from Damascus. There were children who died at a private school in Bab Touma when it was shelled by the rebels [of Ghouta]. My dad works in Bab Touma, and his friend next to him died.”

These questions were not necessarily critiques of the film. There was no doubt, however, that the screening made visible the complexities that directors navigate when making a film about communities enmeshed in revolution and war. The many specificities of the local were speaking back to the limited narratives Still Recording was capable of representing. Resonances of class, geography, religious makeup, and traumatic memory were vying for answers in a way that underlined the incongruencies of art and political struggle. Yet the screening was also an opportunity for the filmmakers to enunciate their multiple commitments and make clear why their film could—in fact, should—exist wedged between art and armed struggle. “For us . . . art and death were part of life; next to death, art was happening,” Ghiath affirmed.

The chance to hear the filmmakers’ reflections became an indispensable part of understanding the film. Its authors explained how their political and artistic commitments to the communities they filmed and to the film’s audience were inseparable from one another. This screening brought to mind a larger question Still Recording, like other revolutionary films, raises: Beyond the question of whether a film can carry out all of its commitments to the diverse individuals who collaborate in or engage with it, could cinema also offer something else—a register of how art and struggle in their delicate symbiosis in the days of Syria’s early revolution brought new reflections to bear on political aesthetics?

Still Recording, one of the films produced by Bidayyat for Audiovisual Arts, is part of a larger phenomenon that predates but was accelerated by the onset of the Syrian revolution, namely the decentralization of Syrian cultural production. Intellectuals’ role within cultural production, and in particular with the dominant modes, attitudes, approaches, and justifications for working with Syrian communities, was dislodged and reimagined in a way that transfigured the very concept of “publicly active individuals,” including filmmakers.{2} The mode of translating “peripheral” spaces or underrepresented people for elite spaces that the work of public intellectuals had been limited to, usually undertaken on the basis of a limited visit to a community, was now thrown into question. Behind this change, I argue, was a resurgence of an ethos of iltizam, or political commitment.{3} A younger generation was changing the standards for how committed, publicly active filmmakers should relate to and represent the conditions of the Syrian everywoman.{4}

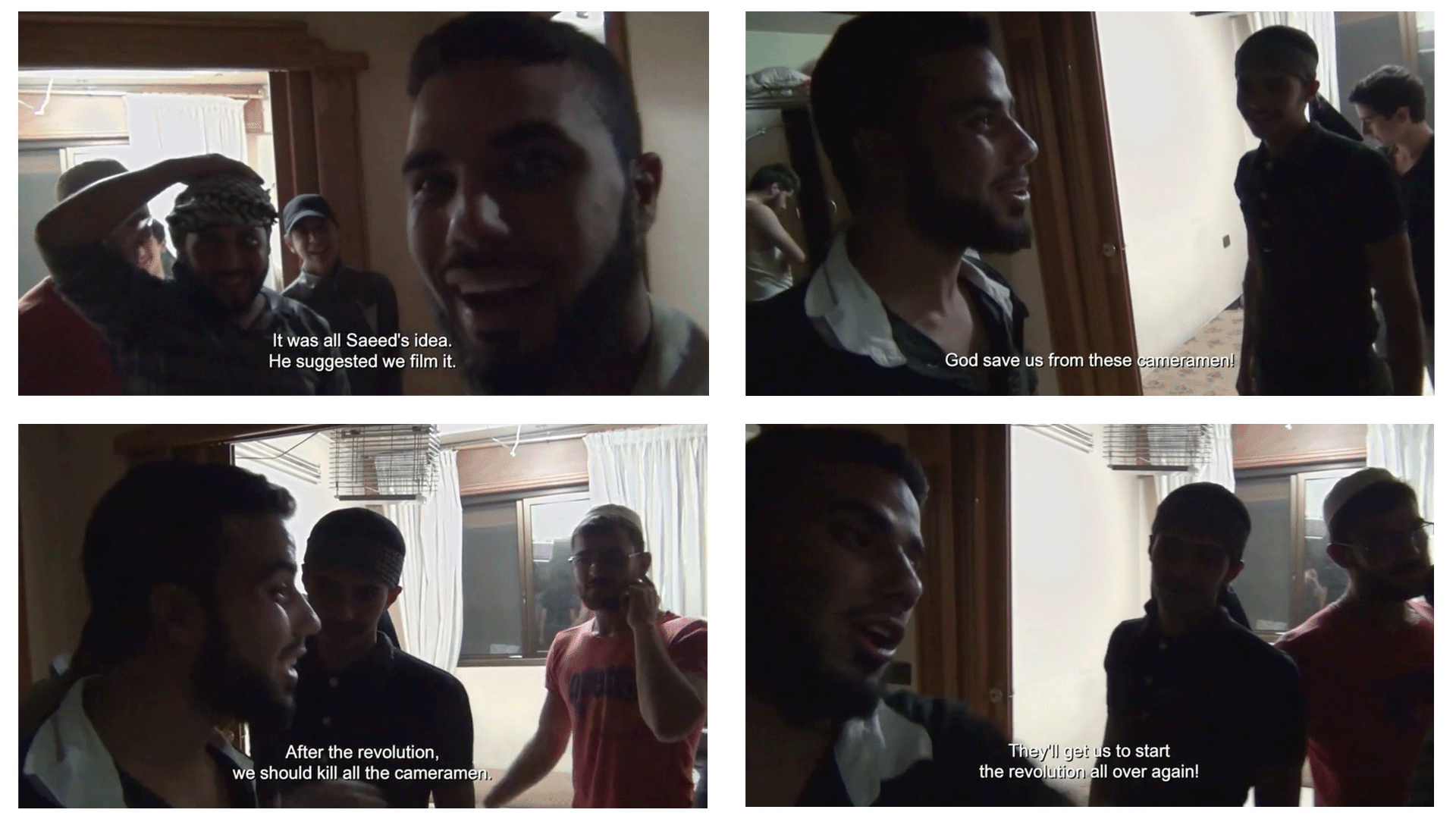

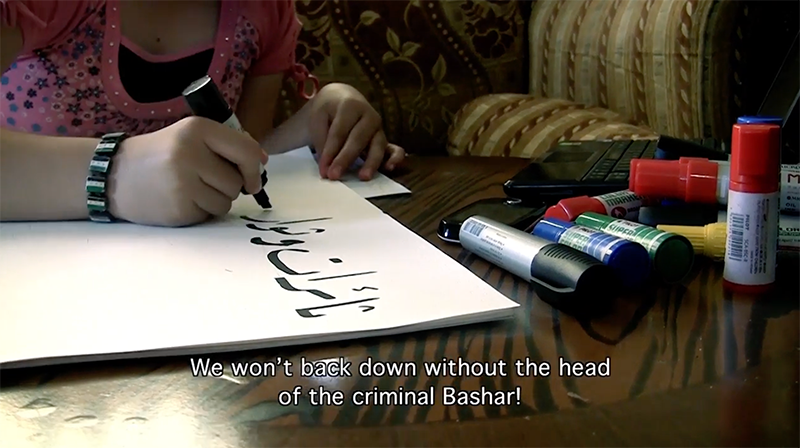

Excerpt from STILL RECORDING (Saeed al-Batal, Ghiath Ayoub, 2018). Courtesy of Bidayyat.

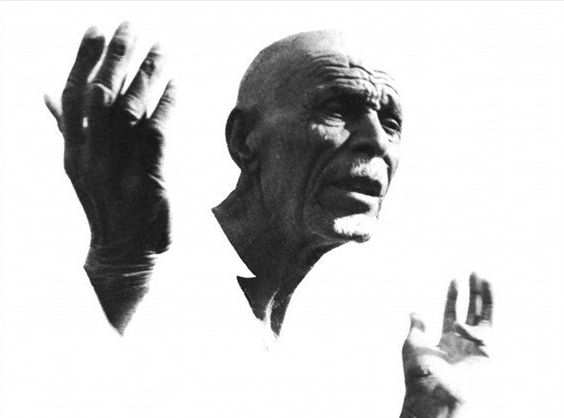

For generations of Syrian filmmakers, especially those who categorized their work as fiction, the notion of iltizam, influenced by the Sartrean idea of littérature engagée, was a popular ethos reflected in how they chose and represented their subjects.{5} Rasha Salti writes of the early, prolific years of Syria’s National Film Organization in the 1960s, in which “everyday people, the illiterate peasants, the poor and the wretched of the earth, were now at the core of the national imaginary in contrast with the sophisticated, urban elites.” Everyday people’s “unwavering commitment to challenge injustice” was seen as “intuitive and fearless.”{6} In the margin of leeway that existed in Syrian cultural production despite regime censorship, filmmakers navigated between critiquing, on the one hand, social and political conditions and, on the other, the contradictions of the liberation ideologies that promised to improve these conditions. Before their eventual disenchantment, for the first half of their careers Saadallah Wannous and Omar Amiralay were strongly influenced by notions of iltizam. In the documentary they collaborated on, Everyday Life in a Syrian Village (1974), the two men agreed to return to Syria to record a panorama of national realities, “in a village, an urban neighborhood, a factory, a school.” According to Amiralay, “Behind this was a desire that we ourselves could discover these realities we were not familiar with: rural life, the popular sector, the conditions of Syrian workers.”{7} This form of iltizam was driven by an ideological impulse to capture rural realities but not share closely in them. There was a belief that filming such realities, and thereby capturing and understanding them, could offer liberatory proposals, even when the film itself wasn’t based on strong ties to a community. In the wake of Amiralay and prior to the 2011 revolution, a few other documentaries addressed rural hardship and the political concerns of marginalized Syrians. Ammar al-Beik’s They Were Here (2000) meditated on the exploitative conditions lived by workers in a steam locomotive factory in Damascus. Nidal Al Dibs’s Black Stone (2006), made with UNICEF, was an exposé of the violent upbringings of children living in the Damascus suburb of Al-Hajar Al-Aswad.

EVERYDAY LIFE IN A SYRIAN VILLAGE (Omar Amiralay, 1974).

EVERYDAY LIFE IN A SYRIAN VILLAGE (Omar Amiralay, 1974).

Following the start of the 2011 revolution, regime repression of protesters and the media industry’s sensationalist portrayals gave rise to urgent new questions regarding the representation of violence. In response, Abounaddara, the anonymous collective that was uploading weekly shorts in solidarity with the revolution, articulated a discourse around the need for dignified images of Syrians. Building on Walter Benjamin’s insight that “political commitment, however revolutionary it may seem, functions in a counter-revolutionary way so long as the [author] experiences his solidarity with the proletariat only in the mind and not as a producer,” Abounaddara argued that

the Syrian revolution seemed to challenge those power relations between author and producer. . . . That’s what one hoped when a new generation of independent activists and artists arrived on the scene. They were actively participating in the representation of Syrian society, monopolized until then by the Syrian state or the media and culture industry. . . . Dignity is compromised when Syrians are unable to become the producers of their own image. So, if Syrian image-makers want to reinstate the dignity of their compatriots, they must seize the means of the production of their own image.{8}

As a way of ameliorating the violence wrought upon everyday Syrians through the dissemination of dehumanizing images, rigorous standards had to be applied when deciding what images should be produced and circulated. In their filmic and discursive work, Abounaddara proposed that Syrians’ images and voices should stand alone, relying on the shared understanding between and overlapping identities of subject, author-producer, and audience.

If the Syrian state, as well as the global media and culture industry, was unfit to represent everyday Syrians, who was fit for the task? By alluding to Benjamin’s call for authors to become producers in solidarity with the proletariat, Abounaddara’s manifesto shifted focus toward establishing a proximity to the revolution and its participants. In the increasingly complex terrain for the consumption of film and media that exploded post-2011, substantial relationships were forged between filmmakers and revolutionary actors. For the films produced at Bidayyat, this practice was exemplified in the material filmed as well as the films’ mode of production and distribution.

This essay turns to two of Bidayyat’s films, Our Terrible Country (2014) and Still Recording, and five of its filmmakers, Mohammad Ali Atassi, Ziad Homsi, Ghiath Ayoub, Saeed al-Batal, and Roshak Ahmad, to examine shifts in the relationship between documentary filmmakers and revolution in Syria. It’s based on three years of fieldwork and approximately thirty interviews with politically committed Syrian cultural producers from different generations about how the duty to “go to the people,” in the words of the late dissident academic Hassan Abbas, has shifted since the 2011 revolution.{9}

The resurgence of iltizam among young filmmakers and the older generations who allied with them indicates that, in the new media landscape carved out by the Syrian revolution, having proximity to, being enmeshed in, and holding oneself accountable to the communities one made work with became the political and ethical ground of cultural production. This form of solidarity offered an alternative to the discourse on sacrifice that previously imbued iltizam and made nearly impossible demands on its proponents. At the same time, this new form of iltizam—which emphasized an approach to filmmaking based on being accountable to rather than speaking on behalf of communities—has allowed filmmakers to bridge class, rural-urban, and sectarian divides in order to create work “nearby” communities in precarious and politically urgent situations.{10}

****

From its outset, Our Terrible Country reveals a generational divide between its two protagonists, one that challenges the model of the Syrian filmmaker and intellectual of decades prior, while ultimately showing how two figures who play different roles in the revolution are brought together through a shared sense of iltizam. In an early scene, twenty-four-year-old Ziad Homsi asks others to film him as he puts his camera down to pick up arms. He sends a message to a sniper who fired a bullet into his shoulder during the battle to take the Medical Tower of Douma. Ziad is a practicing Muslim raised in Douma, a working-class, semirural suburb of Damascus. His own story is part of the regime’s historical oppression of Douma’s residents, not least Ziad’s father, a longtime political prisoner.{11} Ziad actively transmits the situation in Douma and other parts of the country around Syria and abroad through his beautiful photography and his decision to codirect the film—in many ways, the work of a public intellectual.{12} He films his foil, Yassin al-Haj Saleh, a generation older than Ziad and “one of the few intellectuals who participated clandestinely in the Syrian uprising since its earliest days in 2011,” as the film’s synopsis reads.{13} Yassin’s intellectual-author role is flipped—the intellectual who historically would represent the people is here represented. Ziad shows great respect for Yassin’s analytical power and the guidance he provides for the revolution from the standpoint of Douma.

“It is important for a writer like me to live the situation he writes about. And it’s important for an intellectual to want to live with the people and in the same ways as the people whom he is part of, and to try and understand their situation,” Yassin narrates toward the beginning of Our Terrible Country.{14}

Yet, in the reconfigured set of priorities that emerged from the revolution, other figures and roles also attained symbolic and material value. The momentary ability to live in Douma and oust the regime was only possible through armed struggle, which most intellectuals of an older generation (unlike Ziad and his generation) didn’t engage in. Ira Allen compares these roles in terms of labor:

[Ziad’s] bodily presence on the screen enables the very filming of that body and all others. . . . [Yassin] is the doctor of the revolution, yes . . . [but] he is more witness than effective laborer, by contrast with Ziad. . . . And yet, if Ziad is fighting the war, Yassin is imagining . . . what it might yet be besides merely war, . . . something that will only matter in Syria once a war has been won by someone who can then have time for all of those things.{15}

But Our Terrible Country also complicates the assumption of a neat binary into which intellectual and fighter fall, as if sacrifice does not imbue the lives of both intellectuals and soldiers.

The shared burden of sacrifice and its weight on the film’s protagonists comes to the fore in the penultimate scene of Our Terrible Country. Ziad emerges from his scarring detention under ISIS with profound realizations about the direction of the revolution. “People who want to live should get out [of Syria],” he declares to Yassin. “A young man can handle being inside,” he tells him; he concludes, “You’ve given a lot. It’s enough. Get out,” referencing Yassin’s commitments to the revolution. While on the road, Ziad learns that his father has been arrested by the regime, while Yassin learns that his brother has been arrested by ISIS. Despite their differences in status and generation, the two men are brought together through a shared commitment and the losses they have had to endure. The scene ends with them hugging and crying in each other’s arms.

We learn in the film’s epilogue that Yassin’s wife Samira Khalil and her three companions who remained in Douma were kidnapped, likely by the local Islamist group Jaysh al-Islam, an event an earlier scene in the film seems to foreshadow. The news brings into focus the tragedy of a choice Yassin was forced to make earlier in the film, when he decided to leave his wife in Douma so she could avoid the dangerous journey to Raqqa, which had recently been seized by ISIS. We are crushed by the weight of Yassin’s burden, the magnitude of his loss and the tragedy of his choice.

In an interview we conducted later, Mohammad Ali Atassi, Ziad Homsi’s codirector, cautioned that, while criticism of Yassin might come easy—the result of converting one man into a figurehead of the revolution—one mustn’t get carried away by an intellectual exercise disjointed from lived experience. It is ultimately this cold analysis, “the inability to grasp the tremendousness of what has transpired,” as Yassin phrased it to me, that these films seem to warn against.{16} The revolution and war spare none who join the struggle. These films eliminate the accustomed distance that directors and intellectuals historically maintained to the Syrians enmeshed in the worst consequences of political injustice. “My work has become so tied to our experiences—prison, torture, killing, forced absence, death, exile,” Yassin later explained, reflecting on the tragic outcome of the revolution. “Representing our experience needs something different.”{17}

****

Still Recording responds to Yassin’s call for a different representation of the revolutionary experience in Douma, this time through the eyes of a younger generation who demonstrate their vision of iltizam, of political commitment to the revolution and to the people of Douma. Still Recording is a documentary shaped out of footage filmed between 2011 and 2015 in Damascus and Douma. Saeed al-Batal began filming when he moved to Douma to work at the media office for the city’s branch of the Free Syrian Army. His focus, however, soon turned to capturing the harsh reality of life under siege. The film opens with the text “This is the story of Saeed and Milad. Two friends inside—and outside—the besieged city of Douma.” Urban, nonreligious, and university educated, Saeed and Milad translate the experience of siege through their worldview in a way that’s relatable to film festivals. But they maintain a distinct sense of commitment to representing the inhabitants of Douma “differently,” as Saeed told me in an interview, his words resonating with Abounaddara’s and Yassin al-Haj Saleh’s declarations.{18}

Aware of how their commitment not only to “go to the people” but to integrate with Douma’s residents differentiated their approach from past Syrian filmmakers, the makers of Still Recording reflect on how Saeed and Milad’s presence was viewed by Douma’s residents. Many of those residents, knowing Saeed comes from an Alawite family in Tartus, joke about his background in a way that reveals that Saeed’s revolutionary affiliations are more important than his sectarian ones. “Everyone in Eastern Ghouta knows Saeed the Alawi from Tartus. They know that I don’t believe in God,” he reminisced in our interview, smiling.{19}

The filmmakers also prompt viewers to reflect on Milad’s and Saeed’s art projects and, through them, on the role of art in times of revolutionary struggle. They film a time-lapse of Milad painting a wall. As night falls, the phrase “Persevere, my homeland” takes shape. Other readings of the film, however, might also prompt the viewer to see Milad’s and Saeed’s art projects as a superfluous imposition on a conservative neighborhood suffering real hardship through a siege.

Throughout, the contradictions of making a documentary under extreme circumstances rear their head. In a scene in which Abu Abdo kneads dough in his new job as a baker, no longer a fighter, he tells his old comrades with a smile to “turn off the camera. . . . Turn off the camera. . . . Damn you media people! I don’t know how you tricked me into this.” Milad responds that soon he’ll have people in Holland watching his film. “Will it bring customers from Holland?” Abu Abdo quips, to which Milad replies, “Imagine your children knowing someone made a film about their dad—a film, cinema!” A moment of jest reveals the larger contradictions and anxieties in which the film was produced, the tensions around making art in times of acute material need. Abu Abdo’s suspicions reveal the material inequalities and extractive practices that frequently characterize documentary filmmaking in Syria and beyond, the one-way traffic in the experiences of precarious communities flowing to a materially comfortable industry and audience, whose wealth rarely flows back. In the moment, Milad defends the act of filming as “cinema,” something higher to aspire to: art. While Abu Abdo highlights the camera’s superfluousness in the face of hunger, Milad discusses filming as a form of survival and a defense against other kinds of violence and destruction: erasure, the loss of revolutionary memory. For Milad, filming is a form of real-time mourning and the construction of a future historical consciousness.

After the film’s production, the filmmakers took steps to counter models of film distribution that focus on film festival circuits in the West. They organized screenings of Still Recording in private homes around Syria, as well as public screenings in Douma, Idlib, Aleppo, Afrin, and Istanbul, the latter as part of a Bidayyat workshop attended by many former residents of Eastern Ghouta, including those who appear in and contributed footage to the film.{20}

Still Recording was created out of the filmmakers’ long trajectory shaping their own vision of iltizam. Before the revolution, Saeed was inspired by residents of marginalized neighborhoods, such as Al-Hajar Al-Aswad, who were fomenting revolution. In our interview, he pointed to generational differences, contrasting these residents’ actions with the posturing of his father’s leftist intellectual circle: “The only difference between them and ivory tower intellectuals is that [Al-Hajar Al-Aswad] residents talk about simple actions and they do them.” Not wanting to speak ill of those who sacrificed their lives for the revolution, while also wanting to learn from these historically charged moments, he told me that he considered Yassin al-Haj Saleh and his cohort in Douma to be part of the “ivory tower” circle. “I [had] a problem with many things, except for the fact that they were there. [laughs] And this is the only thing I love about them. They tried, at least. Actually, what they did was throw themselves from the ivory tower to the ground. They didn’t really have a bridge to come down easily and talk to [residents of Douma].”{21} He said they were “physically there, but mentally not,” contrasting this with his approach:

My approach was: I am the equal of Ali, who used to be a bicycle repairer before the revolution. Inside the revolution, we discovered he is a very powerful machine-gunman. And inside the revolution we discovered that I am a very powerful cameraman. I carry my weapon, he carries his weapon, we are equal. And whatever he is eating I am eating, whatever he is facing I am facing, and whatever is his struggle is my struggle. And when I’m going to talk about sensitive issues I talk to him in his language.

Our Terrible Country and Still Recording ultimately advance a possible way forward through their commentary on solidarity between filmmakers and subjects, entailing an attitude of humility of the former toward the latter.

Saeed al-Batal and Milad Amin present a model for sharing and enduring the burden of siege. Historically, many filmmakers have opted out of sharing the worst consequences of political struggle. Saeed and Milad instead chose to learn from the practices of ordinary Syrians by living in the suburbs and rural areas where urgent political action was unfolding. This produces a situated identity through the filmmakers’ participation in revolutionary struggle. This form of situated identity bypasses questions of how to speak authentically on behalf of others, which typified previous notions of iltizam. Instead, Saeed and Milad forge new models for producing and distributing work made under conditions of war and revolution.{22}

Bidayyat filmmakers, alongside other cultural producers, navigated the revolution in ways that raised questions about whether they were participants or observers, insiders or outsiders, with regard to the realities they sought to represent. The kinds of unfathomable tragedy that both the makers and protagonists of these films lived through and were enmeshed in render questions of judgment problematic. The filmmakers developed a form of iltizam, sharing the revolution’s consequences through a kind of situatedness rarely seen in documentary film.

In these Bidayyat examples, differences between filmer and filmed in terms of socioeconomic class, education, mobility, and proximity to the violence of Syria’s war are still present. They demand that we recognize the limits of these films and continue to push for new ways of forging substantive relationships to the issues and communities we film, and for models of accountability that last beyond a film’s production. But while these films helped to produce a revolutionary consciousness across class, sect, and generational difference, they also neglected to fully picture women as part of that coalition.

In Our Terrible Country, Razan Zeitouneh, who made an enormous revolutionary contribution in spearheading the Local Coordination Committees (LCCs), refused to be filmed. Meanwhile, in Still Recording, women are left out of Douma’s revolutionary landscape. In my interviews with Milad and Saeed, they expressed their view that giving equal weight to portrayals of women in Eastern Ghouta—women who did not normally occupy the same spaces they did—would impose an “ivory tower” approach on their film. It would misrepresent Douma. The reductive dichotomy evoked by Milad and Saeed—of being either “in touch” or “out of sync” with the “masses”—fails to acknowledge the important revolutionary initiatives that foreground gender in their construction of solidarity. In the end, the filmmakers’ focus is on the militarized perspective of the men included in these documentaries, rather than on how revolution and war affect different genders differently.{23}

The films of Roshak Ahmad, some partially funded by Bidayyat and produced by its predecessor Kayani, are an important contribution to thinking through filmmakers’ relationships to revolutionary subjects, specifically the diversity of female subjectivities in revolutionary spaces. The short film Zabadani Women (2012) presents protest traditions and testimonies, reflecting on the motives and experiences of women who were detained for their subversive activities in what one interviewee in the film calls her “rural and conservative town.”

ZABADANI WOMEN (Roshak Ahmad, 2012).

ZABADANI WOMEN (Roshak Ahmad, 2012).

Ahmad’s medium-length documentary 12 Days, 12 Nights in Damascus (2017) likewise offers a unique reflection on gender solidarity when filming armed struggle.

In Al-Hajar Al-Aswad, people were dying from shelling, more than any of the other military fronts I’d stayed in. . . . I decided to film them so extensively that they forgot I was there and could be completely natural, no questions or interviews. I even preferred not to speak at all so that they completely forgot I was there—an eye that only observes and documents what’s happening. They didn’t pay attention to me. I wrapped a scarf around my head, and they just thought I was a guy from a brigade filming them (which was normal for every brigade), not a journalist. Abu Omar, the protagonist of the film [and his openness toward me] was why I decided to make the film—he really acted completely different from the other fighters. Today I really see him as exceptional. . . . With time, when I saw how this brigade behaved and how I lived with them, slept alongside them, and how they treated me with such equality, not better not worse, me like them, . . . I lost some of my objectivity at some point, but that didn’t affect the film.{24}

These were Roshak’s last moments in Syria before being indefinitely exiled. Holding her camera on the frontlines of the battle in Yarmouk, she was as exposed to death as the FSA gunmen next to her.

Despite Roshak’s silence and social camouflaging, the film makes it apparent that the brigade knew she was a woman. The brigade’s responses to her visibility provide a fascinating glimpse into their collaboration with her on the common goal of filming a documentary amid armed struggle. They not only subvert social codes by allowing her to sleep and eat next to them, but prioritize her work within the military actions of the brigade. Roshak’s attempt at camouflaging is a sign of deference to armed struggle despite her personal critiques of it; while she disagreed with the militarization of the revolution, she found herself committed to closely accompanying the turn the revolution took.{25} Her social camouflaging also makes explicit her enmeshment in this brigade, testifying to the relationship she formed with those she filmed.

Roshak’s motives for making the film reveal her preference for a decentralized cinema, one constituted by practices involving the communities from which her films come forth. These producers bring with them ideas for how to approximate lives and realities that feel far from the cinematic world. Their films offer essential reflections on how to forge relationships between subjects, author-producers, and audiences, bringing forth a new form of iltizam and breathing new life into the evolving relationship between film and revolution.

Title video: They Were Here (Ammar al-Beik, 2000).

{1} See also Saeed al-Batal, “I bear the camera like a shield: No one escapes the massacre, except the dead,” Bidayyat, May 6, 2014.

{2} Yassin al-Haj Saleh uses the phrase “publicly active individuals” in Our Terrible Country (2014). On the role of intellectuals in cultural production, see Katy Montoya, “‘Loving the Revolution but Hating the People’: On Reorienting Syrian Cultural Production Towards Syria’s Revolutionary Masses” (master’s thesis, Princeton University, 2021).

{3} Taha Hussein was the first to coin the Arabic term for “literary commitment” (iltizam al-adab), after translating Sartre’s essays from Les Temps Modernes. This term brought with it a shift in the understanding of writers (and later, other cultural producers) as motors of social change. See Verena Klemm, “Different Notions of Commitment (Iltizam) and Committed Literature (al-adab almultazim) in the Literary Circles of the Mashriq,” Arabic & Middle Eastern Literature 3, no. 1 (2000): 51–52.

{4} Hanan Toukan, “Whatever Happened to Iltizam: Words in Arab Art after the Cold War,” in Commitment and Beyond: Reflections on/of the Political in Arabic Literature since the 1940s, ed. Friederike Pannewick and Georges Khalil (Wiesbaden, Germany: Reichert Verlag, 2015), 347.

{5} See Yoav Di-Capua, “Changing the Arab Intellectual Guard: On the Fall of the udaba’, 1940–1960,” in Arabic Thought against the Authoritarian Age: Towards an Intellectual History of the Present, ed. Jens Hanssen and Max Weiss (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 41–61.

{6} Rasha Salti, “Critical Nationals: The Paradoxes of Syrian Cinema,” in Insights into Syrian Cinema: Essays and Conversations with Contemporary Filmmakers, ed. Rasha Salti (New York: Rattapallax, 2006), 27.

{7} “Omar Amiralay: ‘Documentary, history and memory,’” DI/VISIONS: Culture and Politics in the Middle East, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, December 8, 2007–January 13, 2008, video, 30:49. Author’s translation.

{8} Abounaddara, “Dignity has never been photographed,” documenta 14, March 24, 2017. Walter Benjamin, Understanding Brecht, trans. Anna Bostock (London: Verso, 1998), 91.

{9} Hassan Abbas, interview with author, Beirut, June 2019. Author’s translation. The phrase is reminiscent of “go to the masses,” uttered by the teacher interviewed by Omar Amiralay in Everyday Life in a Syrian Village (1974).

{10} This approach of working “nearby,” in the words of Trinh T. Minh-ha, “requires that you deliberately suspend meaning, preventing it from merely closing and hence leaving a gap in the formation process. This allows the other person to come in and fill that space as they wish. Such an approach gives freedom to both sides and this may account for it being taken up by filmmakers who recognize in it a strong ethical stance. . . . While this freedom opens many possibilities in positioning the voice of the film, it is also most demanding in its praxis.” Erika Balsom, “‘There Is No Such Thing as Documentary’: An Interview with Trinh T. Minh-ha,” Frieze, November 1, 2018.

{11} Souad Khabiyya, “ابن دوما” [Douma resident . . .], Zamanalwsl, October 14, 2013.

{12} The difference in trajectory of the two protagonists is also very notable, as Ziad’s experience being kidnapped by ISIS may be the reason behind his later decision to renounce his association with the film.

{13} “‘Our Terrible Country,’ a Film by Mohammad Ali Atassi and Ziad Homsi,” Bidayyat, May 6, 2014.

{14} Taken from Yassin al-Haj Saleh, “في وداع سورية … مؤقتاً” [Farewell to Syria for now], Ahewar al-Mutamadden, October 14, 2013.

{15} Ira Allen, “Falling Apart Together: On Viewing Ali Atassi’s Our Terrible Country from Beirut,” Screen Bodies 2, no. 2 (2018): 82–83.

{16} Yassin al-Haj Saleh, interview with author, Berlin, July 2019.

{17} Al-Haj Saleh, interview with author.

{18} Saeed al-Batal, interview with author, Leipzig, July 2019.

{19} Al-Batal, interview with author.

{20} Al-Batal, interview with author.

{21} Al-Batal, interview with author.

{22} Authenticity is a concept that recurs throughout the historical work on Syrian cultural production by Alexa First and Max Weiss, for example. See Alexa First, “Cultural Battles on the Literary Field: From the Syrian Writers’ Collective to the Last Days of Socialist Realism in Syria,” Middle Eastern Literatures 18, no. 2 (2015): 153–76; and Max Weiss, Revolutions Aesthetic: A Cultural History of Baʻthist Syria (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2022).

{23} See Maria Al Abdeh’s and others’ work with Women Now for Development; for example, Zahra Ali, Gender Justice and Feminist Knowledge Production in Syria, ed. Maria Al Abdeh and Champa Patel (Paris: Women Now for Development, 2019).

{24} Roshak Ahmad, virtual interview with author, January 2022. Author’s translation.

{25} Ahmad, interview with author.