A Wry Smile: On Overlapping Generations

Stefan Tarnowski & Kareem Estefan

There’s a scene shot by Abdallah al-Khatib in the midst of the siege of Yarmouk, when the small Palestinian suburb of Damascus had been cut off, when, in Khaldoun al-Mallah’s words, “space was tight and time spacious.” The camp had been bombed by the Assad regime, its neutrality breached when it sheltered Syrian revolutionaries and militias, and later it was infiltrated by ISIS. At each stage, Assad forces and their allies responded by placing Yarmouk under starvation siege.{1} Centered, with a twig in one hand and some mangled plastic in the other, Abu Ra’fat sits cross-legged in the rubble and speaks directly to the camera, addressing the “international community”:

I am here awaiting return to the West Bank and Gaza.

Our martyr, Abu Ammar [Yasser Arafat], carried an olive branch in one hand and a rifle in the other.

And you exiled him from Jordan.

You expelled him from Syria.

You chased him out of Lebanon.

We want to go home!

Or die and be buried here.

As he speaks, Abu Ra’fat brandishes the twig and starts to pound the mangled plastic against the rubble. We can’t see Abdallah al-Khatib’s face behind the camera. But as the elder’s tragic yet wooden discourse is overtaken by anger, one can’t help but imagine a wry smile forming on the young activist’s face.

Abu Ra’fat appears frequently in Little Palestine (Diary of a Siege) (2021), in which he spends the days of siege giving speeches, leading chants during protests, attending wedding celebrations, and offering unsolicited advice to Abdallah al-Khatib and other young activists who support the Syrian revolution. He exemplifies an older generation, whether he’s chastising the young for not having enough children or warning them not to join ranks with the revolutionaries who risk breaching the camp’s uneasy neutrality and provoking a repetition of the past, another displacement, another Nakba.{2} The scene in the rubble didn’t make the final cut, but the image of Abdallah al-Khatib’s wry smile during their encounters lingers. It’s evoked by his generational location and filmic framing, his stance of listening politely to an older generation’s discourse, absorbing the scale of the unfolding tragedy and its historical lineages, while sidestepping their diagnoses of the present and predictions for the future, and allowing the audience to listen in on the comic undertones. Watching on with a wry smile doesn’t simply mock or undermine or critique the agony of their predicament. Wry smiles almost always form unintentionally. It’s a response that betrays both familiarity with this kind of historical and humanitarian discourse as well as relative alienation from it. The comic doesn’t undermine the tragic; the two accumulate and combine. The wry smile, where one side of the mouth twists up in laughter while the other remains deathly serious, belongs to a tragicomic mode that holds its contradictions and paradoxes in unresolved tension.

A few things about the scene exemplify what’s at stake in this issue of World Records. The exchange across a generational divide, to paraphrase David Scott, is paradoxical: successive generations can overlap in the same space and time, while also having distinct relationships to pasts and futures and to the political projects orienting them.{3} For generations to overlap, in this sense, means to coincide fully in time or space but only partially in their respective orientations to politics, history, technology, temporality, narrativity, or an event.

LITTLE PALESTINE (DIARY OF A SIEGE) (Abdallah al-Khatib, 2021).

****

It is important to clarify what we mean, and don’t mean, by generation in this issue. The term generation is frequently used in discussions of technological devices and especially their marketing. Our phones are branded with a generation, as are cars, internet browsers, and even pharmaceuticals. Along these lines, it’s common to understand a generation according to what the sociologist Karl Mannheim—whose 1928 essay “The Problem of Generations” has in recent years become the object of renewed interest—calls a “positivist” conception, quantifiable through biological facts like “lifespan,” a cohort of a certain age born within a certain range of dates.{4} This tendency is evident in the generational terms that populate news stories, memes, and ads, from baby boomers to Generation X to millennials, and from Generation Z to Generation Alpha. Focusing on the intersections of age, demographics, calendrical time, and media-technological development, such terms often obscure differing orientations to events within age cohorts as well as similar orientations across cohorts. By contrast, we are interested in how historical events and conditions interpellate people, across age cohorts, and how generations are generated through their distinct responses to these calls. Generations are not pregiven categories or stable intervals along a timeline, but rather emerge and take shape as they describe, imagine, and act within a historical conjuncture.

In The Long Revolution, Raymond Williams articulates his influential if slippery concept of a “structure of feeling” as that which differentiates a rising generation from its predecessor: “One generation may train its successor, with reasonable success, in the social character or the general cultural pattern, but the new generation will have its own structure of feeling, which will not appear to have come ‘from’ anywhere.”{5} A structure of feeling is, here, a generation’s creative contribution to and departure from its inheritances.{6} For Williams, tradition is the ever-evolving result of a process in which future generations determine which elements of past generations will live on: “Tradition can be seen as a continual selection and re-selection of ancestors.”{7} Within a critical or intellectual tradition, this process can, for example, involve the emergence of a particular narrative genre for historiography, such as tragedy in the aftermath of disenchantment with the anticolonial revolutions, to which a succeeding generation of writers and filmmakers might respond with a wry smile, contributing a comic mode to this prevailing genre when they encounter it in the wake of a subsequent attempted revolution.{8}

Within recent writing in anthropology and intellectual history, the concept of a generation has become a means

to reconstruct in dense, sometimes intimate detail the historical milieu of a person’s thinking and acting in such a way as to draw out the events that have oriented their preoccupations, the events that one might see, looking back, as having animated the problem-spaces in which their intellectual questions—their quarrels, their anxieties, their hopes and horizons, their doubts, their objects—emerged as questions to have answers to.{9}

By taking into consideration the paradoxes and complexities of historical reconstruction, the frame of a generation exposes us to the awareness that even the recent past of a preceding generation might need to be rescued from oblivion, especially in the face of imperial and colonial power. In an essay describing her restoration of Palestinian films looted by Israel, Azza El-Hassan asks whether and how Palestinian filmmakers can use the “visual remains” of a preceding generation’s plundered images: “Does the violence of plundering change the nature of such images and leave us unable, as a society and as filmmakers, to relate to our own visual culture?” Even one’s own recent past might need to be rescued, as Yasmin El-Rifae explores through the authoritarian, atomizing transformations of space and time in Cairo. While the revolution granted her generation its first fleeting experience of public space, the counterrevolution then violently reshaped her generation’s world—and its capacity to share a world intergenerationally, as she describes in relation to her son and his grandmother. Writing from a confined present, no longer oriented by the futures her generation imagined in 2011, she asks, “As a city and a generation still being punished for our past, what does it take to see a future?” El-Rifae’s essay suggests that generations are formed both in imagining possible futures and in reappraising the past, with multiple constellations of temporality coexisting at any moment. Or, as sociologists Mark Muhannad Ayyash and Ratiba Hadj-Moussa argue in their assessment of the role of youth in the 2011 Arab revolutions, one can consider generation a social category without letting it settle into “a final resting place where the ‘new’ generation has ‘arrived.’”{10}

Documentation of the opening of the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, organized by the Palestine Liberation Organization, Beirut Arab University, March 1978.

Documentation of the opening of the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, organized by the Palestine Liberation Organization, Beirut Arab University, March 1978.

Equally, the work of reconstructing a generation’s intellectual milieu can help one understand a succeeding generation’s inheritance, one’s place in a tradition in spite of historical discontinuities and ruptures. Fundamental to this approach is a kind of critical generosity, which takes the artworks, intellectual productions, or political positions of preceding generations not as something to be progressively overcome, but rather, in R. G. Collingwood’s phrase, as “the visible record . . . of an attempt to solve a definite problem,” which a succeeding generation might in turn respond to or react against if they belong to that particular intellectual tradition.{11} In the wake of Past Disquiet, the research, publication, and exhibition project initiated by Kristine Khouri and Rasha Salti, which reconstructs a global Palestine solidarity movement and a set of transnational artistic and political ties around the largely forgotten 1978 International Art Exhibition for Palestine, Khouri and Salti reflect on the schisms between then and now, the ways that young Palestinians are reinvigorating traditions of militancy and solidarity, and the role of media technologies in shaping the cultural production of distinct generations of Palestinians. In Fadi Bardawil’s account of his interviews with an older generation of defeated leftist militants and intellectuals, a reflexive meditation on what he calls the “vertigo” of intergenerational dialogue, he quickly becomes aware that he’s not “broadcasting the same signal [he is] receiving.” Through historical reconstruction of a generation’s intellectual milieu, his essay reveals how a past generation’s theoretical impasses and propositions have a bearing on the present’s predicament, and how the work of biography can become fundamentally autobiographical. As such, while the concept of a generation has been an important framework for thinking through the problematics and complexities of historical reconstruction, it’s ballasted in this issue of World Records by a focus on generational construction, on a younger generation’s formation: the mix of sympathy and antagonism, the eye rolls and wry smiles that are typical of a younger generation’s responses to apprenticeship and cultivation, along with the kinds of discipline and disobedience they can elicit.

Abdallah al-Khatib’s film is a case in point. It was produced by Bidayyat for Audiovisual Arts, on which this issue of World Records is centered around a dossier assembled by coeditor Stefan Tarnowski. Bidayyat is a Syrian diasporic organization that was founded in Beirut in 2013 by the journalist and filmmaker Mohammad Ali Atassi before falling dormant in 2022.{12} Nicolas Appelt’s essay frames Bidayyat as a space for exchange, sometimes fraught with conflict, between generations attempting to construct narratives of the Syrian revolution. It highlights the role of Beirut as a center for Syrian cultural production, the “first exile” for many Bidayyat filmmakers. Exile could also become the subject of Bidayyat documentaries, as in films by Orwa Al Mokdad, Yaser Kassab, or Avo Kaprealian, discussed by Appelt; or in Ziad Kalthoum’s Taste of Cement (2017), discussed by Farah Atoui. The dossier is certainly not exhaustive. There’s a wealth of short-form articles on Bidayyat’s website by filmmakers, activists, and writers describing and theorizing the relations between media, revolution, and war.{13} We encourage readers to access these important resources, most of which are available to read in Arabic, English, and French.

Over the course of almost a decade, Bidayyat organized dozens of workshops with young would-be filmmakers—mainly Syrians, but also Palestinians and Lebanese—many of whom were media activists involved in the Syrian revolution. Training young media activists often involved helping them repurpose their activist footage for documentary filmmaking. The would-be filmmakers spent years in Bidayyat’s offices and editing suites, in Beirut and elsewhere, undertaking the assiduous process of turning video clips that were often shot for circulation on YouTube and other social media platforms into documentary films that could circulate on the international festival circuit, in cinemas, on TV, or on streaming platforms. In making films and writing articles, they would come to adopt the professional categories associated with their craft, whether editor, director, or writer.

The process of turning clips into rushes and rushes into experimental documentaries could be long and painstaking, particularly when involving complicated ethical questions and intergenerational negotiations about how to handle and watch images of violence.

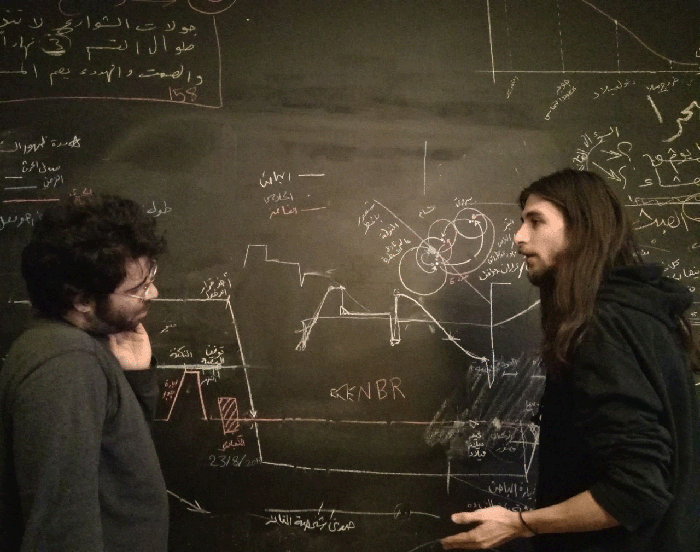

As the accounts by the Bidayyat editors attest, what the activists crossing over thought the footage from inside Syria showed and what it actually looked like for the editors outside were often radically incommensurable. Many attempts at filmmaking misfired, many activists dropped out of the training program, and some didn’t make the cut. The meditation on these exchanges and formations by Qutaiba Barhamji, the editor of Bidayyat’s final two feature films and a frequent trainer during workshops in Beirut and Istanbul, and the conversation about editing between Raya Yamisha, Bidayyat’s long-serving in-house editor, and her mentor, Rania Stephan, give important windows into this process from the perspective of the editor, a figure usually kept on the fringes of the drama of filmmaking, relegated offstage to postproduction. The process of editing occupies an especially central place in Bidayyat’s mode of filmmaking; it comes to look like a stage where the generations could meet and where they were forced into sometimes fraught discussions, negotiations, and disagreements.

The most famous controversy involving Syrian documentary filmmaking was the debate over the “right to the image.” It has generally been seen as an argument between adherents of the free circulation of atrocity images for the sake of contemplating the true nature of the regime’s violence, such as the filmmaker Ossama Mohammed and the dissident intellectual Yassin al-Haj Saleh, and those calling for its restriction through elaborating a concept of “dignity,” such as Abounaddara and Mohammad Ali Atassi.{14} But it has rarely been seen through a generational lens: as a rebellion by an intermediate generation of filmmakers against the practices of National Film Organization (NFO)–funded filmmakers and the discourses of public intellectuals (muthaqaffīn) who, despite distinct stances on political aesthetics, share a common critical and oppositional tradition. Atassi and Abounaddara had both drawn inspiration from Ossama Mohammed’s early films, such as Step by Step (1978), despite recoiling from his later work Silvered Water (2014). In turn, the right to the image has largely been seen as a rule, an attempt by the founders of organizations and collectives to legislate what should and shouldn’t circulate, enacting one more instance of a hegemonic global human rights discourse.{15} But from the perspective of Bidayyat’s institutional practice, publications, and training program, it looks more like a way to inculcate an ethos of dignity—a virtue cultivated through practice among a younger generation of activists who were becoming filmmakers—and an attempt to find ways to help filmmakers handle even the most violent images so that those images could embody the dignity of both filmed and filmer. As such, Bidayyat wasn’t just a workshop where trainings took place and films got made. It was an institutional structure that allowed young filmmakers to maintain control over their own images in the face of market and media pressures. It was also a place where activists such as Saeed al-Batal could reflect on their struggle with images, a place where technique and knowledge weren’t alienated in the process of production, however imperfect the outcome for a first-time filmmaker.{16}

Ghiath Ayoub and Saeed al-Batal in the Bidayyat production office while editing STILL RECORDING (2018).

Ghiath Ayoub and Saeed al-Batal in the Bidayyat production office while editing STILL RECORDING (2018).

It’s easy to idealize this mode of documentary film production for its artisanal quality, to muse on the ways it managed to shelter filmmakers from the violence of the market, and to gloss over the contentious and combative relations that frequently underlay the process. As the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu once noted, it’s through conflict that borders are established between generations, defining where one ends and the next begins.{17} These conflicts between generations of filmmakers and intellectuals predate the Syrian revolution and Bidayyat, as revealed, for example, in a combative interview between Mohammad Ali Atassi and Omar Amiralay.{18} And the conflicts continued once Bidayyat was established as an institution. For example, early on there was a decision to eschew anonymity at Bidayyat. The upside of anonymity was its coherence with the activist practice of pseudonymity—necessary to protect one’s identity in the face of the Assad regime’s violent crackdown—and with the precedent set by Abounaddara, the anonymous collective of filmmakers, whose spokesperson Charif Kiwan sat on the board of Bidayyat in its early days. Bidayyat, however, decided instead to attempt to inculcate a positive sense of authorship and ownership in its young filmmakers, in part to counteract the practices of large satellite media companies and big-budget documentary productions, both of which preferred to subcontract anonymous or uncredited activists who were willing to risk their lives for a cause they believed in, and whose footage could be appropriated cheaply and risk-free. But in some cases, imposing the category—or what Mohammad Ali Atassi suggests in his interview is the “status”—of director led to its own misunderstandings and rebellions. In other cases, filmmakers could both benefit from Bidayyat’s funding, networks, equipment, and system of mentorship, and then entirely disown or refuse to recognize the organization and its imprint on their work. As a site for intellectual production, Bidayyat both represents and contributes to a shift in the form that iltizām took, the intellectual’s mode of engagement with “the people” and “the popular,” as Katy Montoya writes, compared to the centralized, state-controlled funding system, the NFO. Bidayyat wasn’t an NFO in diaspora or exile; it intentionally broke with the way film production had been organized in Syria under the Assads, even while maintaining and cultivating a relationship to the region’s documentary tradition, perhaps even reviving a history of cross-regional production.{19}

****

In history and anthropology, if less so in documentary studies, the concept of tradition has been influential for thinking about intellectual production of various kinds.{20} Within that literature, mediation has been theorized as a recursive part of a tradition’s constitution, where a certain kind of media object, such as an Islamic cassette sermon, can be the bearer of tradition while also cultivating certain kinds of subjects through the formation of their senses and sensibilities.{21} Mediation, in this sense, is the process linking a tradition’s discourse with its embodiment.{22} Together with El-Hassan, however, one might ask: To what extent are traditions of documentary cinema available to contemporary filmmakers in the region? How is a documentary tradition preserved and narrated in the face of material obstacles such as the “inaccessibility of much of what was produced before the digital age . . . due to the disastrous lack of film archiving in the region, which is usually related to war and conflict and/or inadequate state intervention”?{23}

“In my short video essay about Jawherieh [cofounder of the Palestine Film Unit], REMAKE OF A REVOLUTIONARY FILM (2019),” contributor Azza El-Hassan writes, “the narrative begins prior to loss, at a moment when Jawherieh still thought that a homeland . . . might flourish, could be taken for granted.” Frame grab from REMAKE OF A REVOLUTIONARY FILM (Azza El-Hassan, 2019).

“In my short video essay about Jawherieh [cofounder of the Palestine Film Unit], REMAKE OF A REVOLUTIONARY FILM (2019),” contributor Azza El-Hassan writes, “the narrative begins prior to loss, at a moment when Jawherieh still thought that a homeland . . . might flourish, could be taken for granted.” Frame grab from REMAKE OF A REVOLUTIONARY FILM (Azza El-Hassan, 2019).

The very idea of a documentary tradition once came under attack in Trinh T. Minh-ha’s canonical essay “Documentary Is/Not A Name.”{24} For Trinh, scholarly “narratives that attempt to unify/purify [documentary’s] practices by positing evolution and continuity from one period to the next” are misguided. As she states in the opening sentence of her celebrated essay, “there is no such thing as documentary.” For Trinh, the notion of a documentary tradition entails submission to an authority, and thus to authoritative claims of objectivity underwritten by its “traditional” class, race, or gender determinants, which she opposes to the critical faculty that documentarians must cultivate in their apprehension of and intervention in reality. But as Erika Balsom notes, while these claims might once have been radical reappraisals of an “ingrained tradition,” they now sound “commonplace.”{25} Our aim is certainly not to engage in anachronistic critique of these arguments from the comfortable vantage of hindsight. However, to call a film part of a tradition—such as the tradition of documentary filmmaking—need not entail reestablishing documentary’s authoritative claims. Instead, it means taking into consideration the institutions and arguments through which filmmakers are formed as such and in which their films are authorized as documentaries—including when those institutions are cobbled together as pragmatic responses to lifeworld-shattering events such as the Syrian revolution. It’s a way of showing that an artist both forms and is formed by a particular milieu with a particular history, which is intellectual, institutional, technological, as well as generational.{26} It’s both inflationary and deflationary, neither allowing for the death of an author by the autonomy of discourse nor sliding into the kinds of rational or creative autonomy associated with the sovereign individual or artistic genius. Instead, it means thinking of these young filmmakers as “both authors and authored,” both producers and produced.{27}

Nadine Fattaleh’s epistolary essay on Omar Amiralay performs (rather than illustrates or explains) what it means to write from within such an intellectual tradition. In a series of letters, Fattaleh addresses the late Amiralay, in many ways the founding father of the Syrian and even regional documentary tradition. She questions him about past events she missed and presses him on present events he is missing following his untimely death just a few weeks before the Syrian revolution. Fattaleh’s essay is inspired by her own long-standing correspondence with Hala Al Abdalla, for whom Amiralay was a lifelong artistic mentor, political comrade, and friend. This correspondence is then mediated through Al Abdalla’s recent epistolary film and act of documentary mourning, Omar Amiralay: Sorrow, Time, Silence (2021). In its density of temporalities and mediations, the essay treads the fine balance between reception and rejection through which critical and intellectual traditions are passed down the generations in the face of death, detention, defeat, displacement, and other ruptures.

Successive generations can overlap in the same space and time, while also having distinct relationships to pasts and futures and to the political projects orienting them.

Thinking in terms of generations and the intellectual traditions orienting them isn’t merely a means to emphasize continuity and orthopraxy at the expense of political, historical, technological, and geographic ruptures and iconoclasms. Fadi Bardawil argues that one can have different “kinds of attachment” to a tradition, quoting the following passage from Talal Asad’s “paradigm-shifting essay” on Islam as a “discursive tradition”:

To write about a tradition is to be in a certain narrative relation to it, a relation that will vary according to whether one supports or opposes the tradition, or regards it as morally neutral. The coherence that each party finds, or fails to find, in that tradition will depend on their particular historical position. In other words, there clearly is not, nor can there be, such a thing as a universally acceptable account of a living tradition. Any representation of tradition is contestable. What shape that contestation takes, if it occurs, will be determined not only by the powers and knowledges each side deploys, but by the collective life they aspire to—or to whose survival they are quite indifferent. Moral neutrality, here as always, is no guarantee of political innocence.{28}

It’s in examining the contestable representations of critical intellectual traditions within different institutional settings that this special issue expands out from the focus on Bidayyat and the Syrian revolution. In Daniel Berndt’s account of the Arab Image Foundation, different generations of artists and archivists both maintain the archive’s continuity and enact radical archival, institutional, and epistemic shifts. The Iraqi organization Sada (2010–15), meanwhile, offered an educational space for a generation of artists that came of age in the crosshairs of the “War on Terror”; here, founder Rijin Sahakian and four of the young Iraqi artists trained by Sada—Sajjad Abbas, Ali Eyal, Sarah Munaf, and Bassim Al Shaker—look back at the dormant institution. A decade on, they reflect on the process of bringing their band of young artists back together, and the problematics that ensued when their work was translated in one of the art world’s metropolitan centers in 2022. Finally, in her account of being haunted by the voices of a colonial past never fully past, Nida Ghouse writes that even when questioning the limits of contemporary artistic forms as modes of archival recuperation in the aftermath of imperial violence, she stands in a relation of complicity with those forms. Despite the discomfort, she is still in some sense(s) constituted by their materiality. Which is to say, being part of a tradition, including a countertradition, doesn’t mean the mere inheritance of unchallenged doxa or praxis. As J. G. A. Pocock argues in a well-known essay, the forms of argumentation available to radicals, conservatives, or other ideal types in relation to a tradition necessarily involve some kind of orientation to that tradition, even in the case of a conscious attempt at iconoclasm or rupture: “There are seams, after all, in the seamless web; or it may appear so to those who receive and wear the garment.”{29}

Gently prizing apart the seams of the documentary tradition in Syria and the forms it took across narrative genres and technological media in the wake of the 2011 revolution was one of the motivations for translating and recirculating a selection of three essays published in Arabic by Sard, written by Khaldoun al-Mallah, Ahmed Amer, and Abdallah al-Khatib. Sard is an online publishing platform founded by a group of young writers during the siege of Yarmouk; we urge readers to browse the hundreds of articles available in Arabic on the Sard website.{30} The essays translated here reflect on the effects of siege on society and the psyche, which siege will tear apart. It’s a genre or perhaps method of writing that Ahmed Amer has described as al-tawthīq al-bālī, “torn document.” The essays are also a glimpse of a milieu from which a Bidayyat filmmaker, Abdallah al-Khatib, emerged. As such, they preempt any false impressions that Bidayyat was singlehandedly forming the actions, ideas, and sensibilities of the young filmmakers with whom it worked. Before Abdallah al-Khatib had attended a Bidayyat workshop, before he knew he would make it out of the siege of Yarmouk alive, he was writing, reading, posting, and exchanging with astonishing writers such as Ahmed Amer and Khaldoun al-Mallah, comedians of tragedy and the dark zones of siege, translated here for the first time.{31} Whether documenting nightmares or the vicious circles of philosophical argument, “they resemble psychic ‘X-ray’ images contrasting with the countless images we have on film depicting the external aspect of this horror.”{32} The essay by Abdallah al-Khatib was written in the midst of siege, the day after witnessing a particular scene, a scene that three years later would be included in the film he made with Bidayyat. It’s a glimpse of his intellectual formation in extremis, as well as an example of the ways that documentary practices could be transduced, how they were transformed as they traveled across media and genre while maintaining some internal coherence.

If, on the one hand, generations are one of the ways traditions are embodied and transmitted, then, on the other, they’re also a mode of temporal orientation, a way of relating to events unfolding in the present or still unfolding in the past, events that are in turn constitutive of a generation’s intellectual questions and preoccupations. Fundamentally, the young Bidayyat filmmakers share an orientation toward an uprising they were at pains to mediate with the technologies at hand, one that differentiates them from an older generation, which was largely marked, scarred even, by “the events” (al-aḥdāth) of the late 1970s and early 1980s in Aleppo and especially Hama that had been left largely unmediated, though still embodied. But the relationship to an event—such as the Nakba or the siege of Hama or the Arab revolutions—continuously unfolds across generations and is thus distinctive and differential. Events, therefore, aren’t mere points in time that index a discrete generational unit; events have “volumes,” as Mannheim argues, and successive yet overlapping generations maintain differential relations to the same event, including when an event is experienced as an inheritance.{33}

In response to their recounting of an event, a younger generation might listen to its elders with a wry smile. And one day, perhaps, exile will also lead them to look back on and smile wryly at their past selves, in spite of the tragedies they have had to endure. In the final decade of his life, Omar Amiralay returned to the scene of his first documentary, Film-Essay on the Euphrates Dam (1970). In the resulting documentary, A Flood in Baath Country (2003), he examined both the state of Assad’s Syria and his past self. There, like Abdallah al-Khatib, he centered and framed his subject frontally, watching on while the small-town official (re)produced the wooden discourse of the Baath and of Amiralay’s own past ideological fervor. It’s another tragicomic moment, although the tragedy is of a different order, as is the comedy. The viewer still can’t see it, but again it’s hard not to imagine the wry smile that formed on Amiralay’s lips as he looked on and back, the past prefiguring the ideas, genres, and gestures of a future generation; a future self smiling wryly at its own past, embodying a tradition.

A FLOOD IN BAATH COUNTRY (Omar Amiralay, 2003).

{1} For an account of the siege and its sources, see Salim Salamah, “The Unacknowledged Syrians: Mobilization of Palestinian Refugees of Yarmouk in the Syrian Revolution,” Confluences Méditerranée 99, no. 4 (2016): 47–60.

{2} For accounts of Yarmouk’s centrality—as “capital of the diaspora”—in the Palestinian diaspora’s imaginary before 2011, see Anaheed Al-Hardan, Palestinians in Syria: Nakba Memories of Shattered Communities (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016); and Nell Gabiam, The Politics of Suffering: Syria’s Palestinian Refugee Camps (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016). Al-Hardan also gives an excellent account of the anxieties many older Palestinians had toward the Syrian revolution.

{3} David Scott, “The Temporality of Generations: Dialogue, Tradition, Criticism,” New Literary History 45, no. 2 (Spring 2014): 160.

{4} Karl Mannheim, “The Problem of Generations,” in Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge, ed. Paul Kecskemeti (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1952), 276–322.

{5} Raymond Williams, The Long Revolution (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books, 1965), 65.

{6} Williams first coined the term in his 1954 book Preface to Film and used it to different ends across his corpus of writing. In his later iterations of the concept, it evokes emergent processes of meaning-making, thinking, and feeling that have not yet coalesced into a “worldview.” See Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), 128–35.

{7} Williams, Long Revolution, 69.

{8} See David Scott, Conscripts of Modernity: The Tragedy of Colonial Enlightenment (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004). For an incisive reading of the experience of temporality in the wake of and beyond the borders of the Arab revolutions, see Nasser Abourahme, “The Productive Ambivalences of Post-revolutionary Time: Discourse, Aesthetics, and the Political Subject of the Palestinian Present,” in Time, Temporality, and Violence in International Relations: (De)Fatalizing the Present, Forging Radical Alternatives, ed. Anna M. Agathangelou and Kyle D. Killian (London: Routledge, 2016), 129–55.

{9} Scott, “Temporality of Generations,” 157.

{10} Theorizing the role of youth in the 2011 Arab revolutions—as they read Mannheim by way of Scott, Abdelmalek Sayad, and Achille Mbembe—Ayyash and Hadj-Moussa emphasize the reversible, interlocking, and fluctuating temporalities of generations. Mark Muhannad Ayyash and Ratiba Hadj-Moussa, Protests and Generations: Legacies and Emergences in the Middle East, North Africa and the Mediterranean (Boston: Brill, 2017), 13. There’s a voluminous literature on the role of youth, and thus generation, in the Arab revolutions. Our aim in this special issue is not primarily to think of generation sociologically alongside other salient categories such as class, race, or gender, but rather to consider the frame of a generation for the purposes of intellectual production of various kinds, whether documentary film or writing.

{11} R. G. Collingwood, An Autobiography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939), 2.

{12} “About Us,” Bidayyat, accessed May 9, 2023. Bidayyat has not closed, but nor is it still functioning as an organization. Its founder and director Mohammad Ali Atassi holds out hope that someone—perhaps from a younger generation—might eventually revive the structure.

{13} “Articles/For Bidayyat,” Bidayyat, accessed May 9, 2023.

{14} See, on the one hand, Ossama Mohammed’s film Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait (2014); Yassin al-Haj Saleh, “تحديق في وجه الفظيع ” [Staring in the face of atrocity], Al-Jumhuriya, May 29, 2015; and on the other, Mohammad Ali Atassi, “الكرامة في حضور الفظاعة” [Dignity in the presence of atrocity], Al-Jumhuriya, June 2, 2015. See also Abounaddara, “Respectons le droit à l’image pour le peuple syrien,” Libération, January 22, 2013; and Abounaddara, “ليس للسوري الحق في الصورة” [Syrians have no right to the image], Al Hayat, April 20, 2017.

{15} See Miriam Ticktin, “Rewriting the Grammars of Innocence: Abounaddara and the Right to the Image,” World Records Journal 4 (Fall 2020).

{16} See Saeed al-Batal, “I Bear the Camera like a Shield: No One Escapes the Massacre, Except the Dead,” Bidayyat, May 6, 2014; or Saeed al-Batal, “Autism,” Bidayyat, June 27, 2014.

{17} Pierre Bourdieu, “‘Youth’ Is Just a Word,” in Sociology in Question, trans. Richard Nice (London: SAGE, 1993), 95.

{18} See the interview with Omar Amiralay: Mohammad Ali Atassi, “عمر أميرالاي يتحدث عن بلد اسمه سوريا الأسد في “الطوفان”: دمّـرنـا الـحـقـائـق فـي الـسـابـق كـي لا نـضـطـر الـى مـواجـهـتـهـا” [Omar Amiralay discusses a country called “Assad’s Syria” in his film “Flood”: We destroyed the facts of the past so we don’t have to face them], Mulhaq al-Nahar, November 16, 2003.

{19} See Kay Dickinson, Arab Cinema Travels: Transnational Syria, Palestine, Dubai and Beyond (London: Palgrave on behalf of the British Film Institute, 2016).

{20} As the concept of a tradition has been translated from the history of moral philosophy to anthropology, Islamic studies, and postcolonial theory, it has undergone a series of modulations. For a partial set of readings we draw on here, see J. G. A. Pocock, “Time, Institutions and Action: An Essay on Traditions and Their Understanding” [1968], in Political Thought and History: Essays on Theory and Method (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 187–216; Alasdair C. MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981); Talal Asad, “The Idea of an Anthropology of Islam” [1986], Qui Parle 17, no. 2 (Spring/Summer 2009): 1–30; and more recently, Wael B. Hallaq, The Impossible State: Islam, Politics, and Modernity’s Moral Predicament (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014); and Basit Kareem Iqbal, “Asad and Benjamin: Chronopolitics of Tragedy in the Anthropology of Secularism,” Anthropological Theory 20, no. 1 (March 2020): 77–96. In film and media studies, to the extent that documentary “tradition” is treated, it is typically diminished through a focus on technological, generational, and aesthetic ruptures; among the finer examples of scholarly texts on documentary tradition, which recognize important continuities alongside ruptures, are Paul Arthur, “Jargons of Authenticity (Three American Moments),” in Theorizing Documentary, ed. Michael Renov (London: Routledge, 1993), 108–34; Linda Williams, “Mirrors without Memories: Truth, History, and the New Documentary,” Film Quarterly 46, no. 3 (Spring 1993): 9–21; and Erika Balsom, “The Reality-Based Community,” e-flux Journal, no. 83 (June 2017).

{21} Charles Hirschkind, The Ethical Soundscape: Cassette Sermons and Islamic Counterpublics (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006).

{22} For the distinction and relation between discursive and embodied tradition, see Talal Asad, “Thinking about Tradition, Religion, and Politics in Egypt Today,” Critical Inquiry 42, no. 1 (2015): 166–214.

{23} Viola Shafik, “Introduction: Histories of ‘Arab’ Documentaries or Documentary Forms South and East of the Mediterranean?,” in Documentary Filmmaking in the Middle East and North Africa, ed. Viola Shafik (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2022), 6.

{24} Trinh T. Minh-ha, “Documentary Is/Not a Name,” October 52 (Spring 1990): 77–98.

{25} Balsom, “Reality-Based Community.”

{26} For a notion of milieu drawn on here and the reflexive relation between a technology and a society, see Brian Larkin, “The Cinematic Milieu: Technological Evolution, Digital Infrastructure, and Urban Space,” Public Culture 33, no. 3 (95) (September 2021): 313–48.

{27} David Scott, “The Tragic Vision in Postcolonial Time,” PMLA 129, no. 4 (October 2014): 802.

{28} Asad, “Anthropology of Islam,” 24.

{29} Pocock, “Time, Institutions and Action,” 193.

{30} See: Sard.

{31} For treatments of tragicomedy as genre and narrative form in Samuel Beckett’s work and its philosophical roots, see Enoch Brater, “Beckett, Ionesco, and the Tradition of Tragicomedy,” College Literature 1, no. 2 (1974): 113–27; Elliott Turley, “The Tragicomic Philosophy of Waiting for Godot,” Modern Language Quarterly 81, no. 3 (September 2020): 349–75. Both cite Beckett’s aphorism: “Democritus laughed at Heraclitus weeping & H. wept at D. laughing. Pick yr. fancy.” Khaldoun al-Mallah’s short-form essay “Shitting on/at the checkpoint,” not translated here, also draws on Beckett’s image of the interconnectedness of tragedy and comedy through those two archetypal Greek philosophers. Abu al-Khuloud [Khaldoun al-Mallah], “لما تخرا عالحاجز” [Shitting on/at the checkpoint], Sard (blog), November 29, 2020.

{32} The phrase is from Reinhart Koselleck’s theorization of the historiographical value of dream during the Third Reich, “Terror and Dream: Methodological Remarks on the Experience of Time during the Third Reich,” in Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time, trans. Keith Tribe (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 217.

{33} Scott, “Temporality of Generations,” 165.