Dear Omar

Nadine Fattaleh

Dear Omar,

You do not know me, but still I feel emboldened to write you this letter. It has been over ten years since your death. You left having smelled only a brief whiff of jasmine, the scent of possibility, carried from shady Habib Bourguiba Boulevard in Tunis and Tahrir Square in Cairo. You departed with a fleeting intuition of the role the image would play in the mass upheaval of your own country. Your untimely passing has added to the mythology of who you once were as a radical and committed filmmaker. Those closest to you have said their parting words, they have written and edited eloquent eulogies in your honor. From them, I have learned a lot about who you were as a person.

OMAR AMIRALAY: SORROW, TIME, SILENCE (Hala Al Abdalla, 2021).

OMAR AMIRALAY: SORROW, TIME, SILENCE (Hala Al Abdalla, 2021).

Omar, my inspiration comes from a film made by your lifelong friend and collaborator, Hala Al Abdalla, entitled Omar Amiralay: Sorrow, Time, Silence (2021). It’s an ode to your friendship, forged through years of speaking out against the political repression of the Syrian regime. It’s about your shared love of cinema, your investment in the activities of a bustling cine-club of Damascus, the years you endured in exile in Paris, and your unflinching commitment to the power of documentary. Shot on the eve of your last encounter with Hala in 2009, you are subjected to the revelatory powers of the camera as you offer somber reflections prompted by the impending death of your mother. Omar, you passed away unexpectedly, on February 5, 2011, shortly after your mother and five weeks before the onset of revolution in Syria.

Omar Amiralay: Sorrow, Time, Silence confounds genre. It features you playing several roles: a son reflecting on the intimacy of caring for his sick mother, a director offering an autobiographical description of his engagement with the documentary medium, a friend and recipient of a letter from an exile, Hala, returning home to her country. The film crosses boundaries: between life and death, beauty and sorrow, reality and film, fiction and documentary. But what interests me most about Hala’s treatment is its epistolary form. The letter allows her to address you with questions and observations about what has unfolded in the past ten years in your absence. Following my first meeting with Hala, the generous conversation she shared with me, I feel a humble impulse to also write you a letter, informing you of the prescience of your work, the afterlife it has acquired among the so-called new generations who did not know you, but still find inspiration in your legacy.

****

Omar,

I am trying to recall how exactly I learned about your life and work. It was definitely years after your passing. I must have read your name in a book and then found most of your films at the click of a button. I know that this seamless access has not always been the case. I watched your films on the small screen of my computer, one after the other, struggling at first to grasp their content or context. It was 2016, the moment when Syria was still newsworthy and films documenting the revolution and its aftermath made their appearance on international festival circuits. I got to know your work as I was trying to understand contemporary films by Syrian directors working across a generational divide, decrying Assad’s authoritarianism at a moment when it seemed to be crumbling.

The central problematic of your generation’s work—starting in the early 1970s—was how to make films that defied the Baath regime even as they utilized the resources of the National Film Organization’s bureaucratic production infrastructure. Any articulation of the relationship between cinema and politics was beholden to this configuration of power. The result was a rich corpus of critical works emerging from the belly of a repressive beast. But the circulation of films was heavily curtailed by censorship and the state’s control over screening and distribution. Syrian national cinema has always been marked by paradox: it’s “a state-sponsored cinema whose most renowned filmmakers offered an alternative, critical and subversive narrative of the ‘national’ lived experience of traumas that directly contested the official state-enforced discourse.”{1}

By contrast, it seemed that filmmaking in the wake of the revolution responded to an utterly different set of conjunctural questions. The moment was wedded to expansive horizons of political possibility and marked by a grander conviction in the power of political image-making. When I began thinking in 2016 about the political efficacy of the digital image, the moment was already rife with challenges. But crucially, the promise that images could be mobilized politically was yet to be broken. The regime’s propaganda machine was at work to discredit activist images as fabrications, or to muddy the discursive grounds so as to undermine the work of the Syrian opposition. Still, media activists coordinated rapid and extensive coverage of events, documenting, uploading, and sharing moments of urban protest to mobilize for the revolution, and later documenting life in besieged cities and the aftermath of aerial bombardment with an abiding faith in the production of evidence, whether for the adjudication of a court or of History. Western hunger for humanitarian narratives was already codifying the norms of documentary filmmaking, but many daring works defied the depoliticized rendering of the Syrian cause for global consumption.

In 2017, Omar, I finished a humble work replete with technological determinism and misguided political proclamations about the power of images and their archives. Part of my initial reading was influenced by an enduring commitment to the praxis of image-makers themselves, who put forward propositions about how video in the context of the Syrian revolution can and should function politically. Portable cameras and accessible platforms, I thought, underpinned a mass upheaval, and the digital medium was a democratizing force that liberated a new generation of Syrian image-makers from the concerns, both technical and political, of your analog generation. While your generation made films that were banned, it seemed that with the revolution the embargo on political critique was finally broken. In her epistolary ode to your work, Hala Al Abdalla reminds us that we should think twice before celebrating the impossibility of censoring digital images. As she notes, the regime went from silencing and subduing through censorship to mutilating, murdering, and terrorizing media activists and filmmakers. Today, I recognize the shortcomings of these attempts at critically theorizing the forces mobilized by the image, and I think that many Syrian activists are also grappling with a growing dissatisfaction with the broken promises of cellphone cameras and the internet, and the related sense of defeat that marks this aftermath we’re living.{2}

[Do you remember, dear Omar?

I filmed these children on a scouting trip with you in our country.

At the beginning of the school year, a teacher could ask these same pupils,

“Who among you wants to go to the blackboard?”

Some of them would raise their hands full of enthusiasm and confidence.

The teacher would then see raised fingers golden with the sun and freedom,

but some have no nails.

They have been torn off.

To punish them, the security forces have tortured them as they torture men, by pulling out their nails.

These children dared to write on the walls of their school, “The people want the fall of the regime.”

(Chanting) “The people want the fall of the regime!”

(Chanting) “The people want the fall of the regime!”]

—Hala Al Abdalla, Omar Amiralay: Sorrow, Time, Silence

Since my initial encounter with your work online, I have rewatched your films several times and shared many conversations about them. In Amman, my hometown, I spent many evenings in dark corners during gatherings of artists and filmmakers recounting memorable scenes from A Flood in Baath Country (2003). Your films featured in conversations during long nights of reminiscing with friends in New York, where I would eventually organize a public screening of a number of your works. In London, a cultural festival arranged a retrospective for you alongside contemporary Syrian filmmakers. Each screening brought to my attention new details and insights that were inflected by the present political circumstances. I speculate that a renewed engagement with your work can offer guidance in this moment of disillusion. I do not claim to occupy the position best suited to write about the reception of your films by young Syrians in the wake of the Syrian revolution; still, I hope to offer some preliminary thoughts as an invitation to others to write a new history of the reception of Syrian cinema.

The first thing I think we ought to learn from you is the courage both to hold on to and to rethink early works, especially those guided by political convictions that no longer withstand the present’s dispensations. Omar, you returned to Syria in the late 60s, armed with an education in militant filmmaking, and your first short, Film-Essay on the Euphrates Dam (1970), was commissioned by the state’s National Film Organization. This experimental work valorizes the construction of the Euphrates Dam, visually mediating what you called a “hymn to the crane” and celebrating the infrastructural modernity that was supposed to revolutionize the countryside. As you would go on to recount many times, Film-Essay is enamored with the aesthetics of the machine at the expense of a critical engagement with the effects that this dawn of modernization had on the life of peasants in the countryside. You do not shy away from acknowledging your misplaced faith in the promise of the state and its deployment of the machine. Many of your subsequent films offer a sharp rejoinder to your past political self, representing what you had left concealed, namely the social and material underpinnings of village life in Syria.

OMAR AMIRALAY: SORROW, TIME, SILENCE (Hala Al Abdalla, 2021).

OMAR AMIRALAY: SORROW, TIME, SILENCE (Hala Al Abdalla, 2021).

****

Omar,

I am interested in how you charted the relationship between cinema and radical politics. In your extended conversation about your body of work with Hala Al Abdalla, you mock and repudiate the naivete of your initial faith in cinema as a tool for ideological expression. You say, “That’s how we started in cinema, as left-wing Marxist filmmakers that saw film as a tool for action, a tool to implement change in consciousness and society. There was a utopian view of the act of filmmaking.” As you explain the development of your trajectory and the coming of age of your documentary language, you seem to consign the lofty concerns for the ideological deployment of cinema to your long-gone adolescent days. Documentary, for you, became fundamentally about uncovering the encounter with the real, even as reality emerges enclosed between several brackets, in other words, severed from the immediacy of the lived context and dramatized through editing and montage.

I refuse to believe that you completely gave up on filmmaking as a militant vocation. I hear in your words traces of thinkers like Benjamin, Eisenstein, Vertov, Marx, Gramsci, and Fanon, among many others, because I have also inherited this theoretical vocabulary and its marked ambivalence toward the democratizing potential of cinema. You talk about the heap of exaggerated theoretical proclamations that caused you, early on, to believe with Walter Benjamin that cinema could burst the prison world asunder by the dynamite of twenty-four frames per second.{3} Of course, you paraphrase Benjamin to question the animating force that particular images can have on the popular consciousness of cinemagoers, who may be moved by seeing their reality relayed to them in a succession of images. But did you really give up on the possibility that film can forge a communal experience? Isn’t it precisely this possibility of drawing people together that produced anxiety in the state? Was this not what caused your films to be banned in the first place?

As you relate to Hala your experience with dramatizing the real in documentary form, the poster for your second film, Everyday Life in a Syrian Village (1974), hangs above you and marks this film’s towering influence. Everyday Life, to me, is a film about accumulation by dispossession in the Syrian countryside. It combines an orthodox Marxist concern for materialist class analysis, a Gramscian affinity for the subaltern voice, and a Fanonian urgency for anticolonial action. The decoupaged image of the impoverished and subjugated peasant, the credible bearer of the truth of rural hardship, is the defining idiom of the film. At the end of Everyday Life, the peasant turns directly to the camera, ripping off his clothes to offer a naked and raw final address: “We are hungry and we are dying.” The film closes with a series of intertitles, which reference the Third Cinema classic The Hour of the Furnaces (1968) as they quote from Fanon:

“We must involve ourselves in the struggle for our common salvation. There are no clean hands, no innocents, no spectators. We must all plunge our hands in the mud of the soil. Every onlooker is a coward, or a traitor . . .”

I have always been fascinated by this biting indictment of spectatorship, particularly because it presupposes an engaged audience for the film and a political organization or framework through which cultural practice could inform militant political mobilization, both of which were becoming increasingly impossible in Syria in the early 1970s, on the eve of the film’s completion. You seem to have been interested in screening Everyday Life among rural and peasant communities, reflecting to them the image of their own dispossession and igniting a form of political awakening through cinema. The film was banned before its release and has been banned ever since, for nearly half a century. But rather than dwelling on the impossibility of the film’s closing address, I want to hold on to the anticipatory relationship it charts between film and a new collective political consciousness.

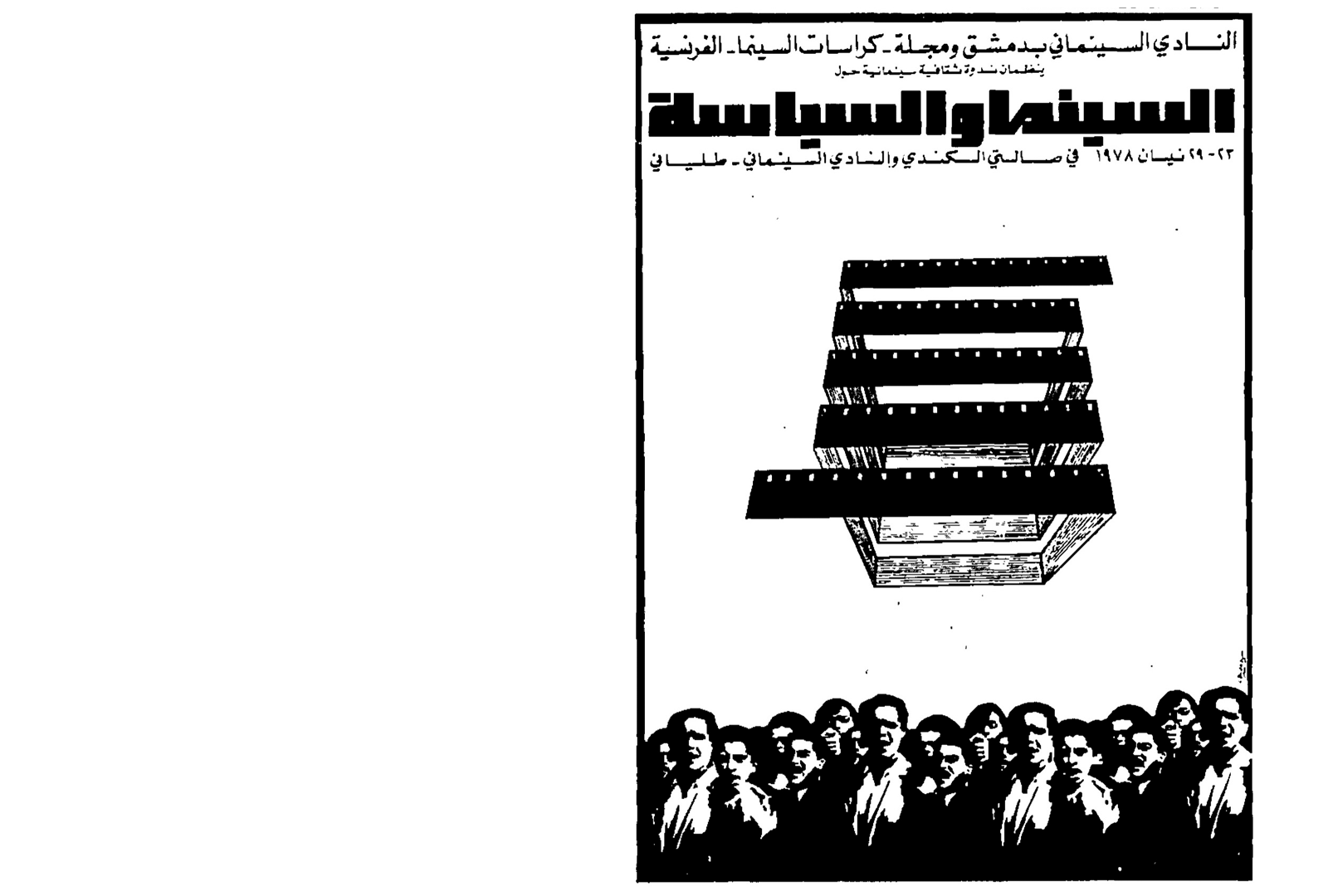

Elsewhere, Omar, I read about the weeklong event called Cinema and Politics that you convened in Damascus in 1978 in the seven-hundred-seat Al-Kindi theater. I found a poster of the event online, but I searched in vain for photographs substantiating that you were really there at this legendary event that brought together Syrian filmmakers with figures like Jean-Luc Godard and Agnès Varda, legends of the French New Wave who were also your comrades. You relay that the Syrian censors banned a number of films, so in place of the screenings the film critic Serge Daney sat onstage and performed a verbal recitation, describing in detail the banned films, filling the void of their impossible appearance. About this event, you are quoted in the New Yorker saying, “It was a screening without an image—an absolutely beautiful happening.”{4} Daney’s rather mischievous account of the events suggests that the prohibition of some films was not the only controversy, and fiery debates between radical filmmakers here (Damascus) and elsewhere (Paris) established fault lines among the audience, some of whom were invested in the radical aesthetics of cinema and others who were concerned exclusively with the political importance of the image.{5}

Between the completion of Everyday Life in 1974 and the Cinema and Politics seminar in 1978, Omar, it seems you were confronted with two inverted cases of the same impossible situation. In the first, a committed film was denied its intended audience; in the second, a committed audience was denied the intended films. Perhaps this is why you gave up on the relational and collective dimension of political cinema?

****

Omar,

Allow me a moment to relate to you a story of attending a screening of your work, as it was shown alongside other films about the Syrian revolution. I hope this will enliven your conviction that anonymous, communal experiences in cinema can amplify the impulse for collective critical reflection.

I have long admired many of the formal elements of your most accomplished work, A Flood in Baath Country, a film that confirms your stature as a great filmmaker. Chronicling the effects of the Euphrates Dam on the small town of Al-Mashi, Flood is a documentary rife with irony and metaphor as it mediates the embodied experience of two key sites for the reproduction of national ideologies: the family and the school. The film is self-reflexively staged in conversation with your early work, as it weaves a political portrait of Syrian society from moments of everyday life in a place ruled by enduring tribal affiliations, which stand in for the inherited Assad regime. Your poetic treatment of the submerged remains of a village, inundated by the dam, would become, unbeknownst to you, an infrastructural prophecy for the deluge that eventually arrived after your passing.

OMAR AMIRALAY: SORROW, TIME, SILENCE (Hala Al Abdalla, 2021).

I learned something new and valuable about the affective power of Flood in the present upon viewing it in the context of a Syrian film festival in London. Sitting in a dark auditorium, I was able to discern viewers who had grown up in Syria, and who thus harbored intimate familiarity with the subject of the film, by tracing the source of outbursts and laughter. Those who had endured years enveloped by the rigidity of the green military school uniform found certain scenes funny, while the rest of the audience, like me, were resigned to a more distant and reserved appreciation of the film.

I read that you returned to Syria in 1991 to make a documentary consisting of fifteen shots describing the fifteen reasons why you hate the Baath regime, a project that would morph and take final shape in A Flood in Baath Country.{6} In its ability to capture the visceral experience of schooling in Syria, the film also retains the spirit of its genesis as a list of deeply personal grievances against the Syrian regime. Omar, I doubt Syrians living in exile in the wake of the revolution and its violent aftermath need a visual reminder of more past violence. But still, screening Flood today is important because of its power to evoke collective feelings that prompt intimate recollections. It feels as though viewers are invited to add to your list of grievances, which have undoubtedly multiplied over the past decade.

In conversations about the film, one of my friends recalled how Flood reminded him of an incident with his school headmaster, which marked the day he learned of the violence unleashed on those who reject the synchronization of their bodies in the space and time of the nation. Many of the comments that have accrued on YouTube since the film was uploaded ten years ago recall similar stories about the refusal to adhere to the corporeal orchestration of Baathist ideology at school. For example, an anonymous user describes how, after learning about the brutality of the Hama Massacre in 1982, he refused to sing the national anthem, preferring instead to silently mouth the words every morning. Omar, I think you would appreciate this cunning, minor disavowal of power by someone who, like you, clearly understood how the regime worked on bodies to project signs of outward subservience onto citizens. A Flood in Baath Country, seen through the window of the present, can allow those who harbored doubts through years of self-imposed silence to share and make audible their experiences in the presence of others.

A FLOOD IN BAATH COUNTRY (Omar Amiralay, 2003).

A FLOOD IN BAATH COUNTRY (Omar Amiralay, 2003).

****

Omar,

Let me remind you of another instance in which you discuss the relationship between cinema and political action. In Meyar al-Roumi’s A Silent Cinema (2001), you show us the 16mm camera that you kept long after you switched to more advanced filmmaking technologies. You describe how you used it in your early student days in Paris, not to record traces of actions as they manifested in public, but to inscribe in your memory that fabled revolution of May 1968:

I was fascinated by the street movements and I plunged myself into them. The very cinematographic act then became more important than shooting itself. One had to be there, with his camera, just as things happened. The camera became the eye; there was a superimposition process. You can only see through the lenses, even with no film in the camera. That’s why I sometimes shot scenes with no film. But I shot them to get the image fixed in my mind, not on film.

Here you relate an understanding of the cine-eye, the superimposition of the lens with the perceptual capacity of the eye, which is a metaphor as old as the apparatus itself.{7} You registered many of the enduring legacies of May 1968 in Paris without a physical trace. Among them are theories of the spectacle born out of the experience of urban protest that transformed passive onlookers into active agents in the struggle for collective ownership over space.{8} I suspect that through the camera, you were able to overcome the so-called passivity of viewing, the illusion that viewing equals inaction. Tracking movement in the street through the viewfinder, which mediates only a momentary flicker of events, I think you were able to reunite seeing with the capacity to remember and the power to act. The camera offered you, in that moment, not an aid to perception but a form of political action administered through the body’s presence in the space and time of unfolding events. It allowed you to partake in a collective political consciousness working to rescript the protocols of urban space.

The cine-eye, as a figure of speech, allows us to think of the process of perception as it has developed against a rapidly evolving media landscape. But let’s scrutinize the technical fate of the image as it leaves the analog age of photochemicals and enters the digital age of pixels. Today, the near-instantaneous transmission of digital images is said to accelerate the process of mediation. I don’t fully subscribe to such sweeping proclamations. However, there is certainly some truth to the claim that the so-called “real-time” rhythm of media has begun to close the feedback loop between event and image. During the Syrian revolution, the visibility of protests was immensely important. The circulation of images was closely entwined with the contestation of places. Mediating the presence of bodies in space directly challenged the state’s narrative and political control.{9}

Today, more than a decade after the first dreams of visibility as a conduit to Syrian liberation, we’re waking up to the failures of the digital image to secure a better future. The utopian promise of video-based documentation and testimony has become an illusion for people who courageously filmed, shared, and transmitted images from every political and perspectival angle in Syria. Unburdening the political image means questioning the abiding confidence in the journalistic or legalistic impulse for documentation, the ethical imperative to bear witness, and the purported power of uncovering the truth. Shorn of beliefs in the image as an agent in the political force field, should we abandon the camera?

Omar, I don’t think I’m ready to give in so easily. In this moment, there is a lot to learn from your description of the cinematic act, which situates the image as the means for action rather than its end result. Analog film may decay, rot, lose resolution, or accumulate layers of dust, while digital video may accelerate through download, upload, and remix only to be historicized, reinterpreted, and collected for purposes of preservation, archiving, and memorialization. But perhaps the real power of images of the past is the way they are retained in memory, where they continue to invigorate and enliven demands for dignified life. What is remembered never dies.

Did you really give up on the possibility that film can forge a communal experience?

****

Finally, Omar,

Following your death, a group of committed film programmers, many of whom were your friends, insisted on staging a commemorative screening in your resting place, Damascus. A friend of mine was there to watch A Flood in Baath Country for the first time. In the middle of the screening, he claims, the projector suddenly stopped working. It’s unclear if this was an accident or if someone had followed orders to pull the plug. At this point, discerning the difference between a technical error and a politically motivated act of censorship is unnecessary. Imaging technologies sometimes fail of their own accord. Certainly, the promise that the camera would offer salvation has betrayed many who filmed to save their lives in the days of the revolution and the brutality that ensued. I’d like instead to ask, What did the conversation look like when the successive relay of frames was aborted at your postmortem screening? Did the situation breed anxiety and trepidation or a bolder license to speak out in defense of your legacy?

Today, Omar, we need your adolescent fervor, the boldness with which you decry passive viewership and mobilize, through cinema, for a vision whose contours are not yet defined. We need your work to guide in the act of seeing through the prosthetic of the camera and the retrospective labor of assembling fragments of the real, with the hopes that there we will find traces of political projects not yet born. We need to continue to look beyond predetermined manifestations of endemic violence, and to remain resolute in producing other images to see beyond the burden of the present.

Acknowledgments: This work benefits, first and foremost, from the generosity of Hala Al Abdalla, whose work has breathed new life into the legacy of the late director Omar Amiralay. I’m additionally thankful for conversations and insights with those intimately engaged with the Syrian revolution: Khaled, Ram, Yamen, and Basil, among countless others. I am grateful to Stefan Tarnowski for the invitation to contribute and for all the conversations over the years about Syrian cinema. Finally, I thank Kareem Estefan, Nour Annan, and Mariam Elnozahy for their editorial input.

Title video: Omar Amiralay: Sorrow, Time, Silence (Hala Al Abdalla, 2021)

{1} Rasha Salti, “Critical Nationals: The Paradoxes of Syrian Cinema,” in Insights into Syrian Cinema: Essays and Conversations with Contemporary Filmmakers, ed. Rasha Salti (New York: Rattapallax, 2006), 21.

{2} See Stefan Tarnowski, “Both Authors and Authored: Our Memory Belongs to Us and the Tragedy of Activism in Syria,” Film Quarterly 75, no. 2 (2021): 59–67.

{3} Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility: Third Version” [1939], in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, vol. 4, 1938–1940, trans. Harry Zohn and Edmund Jephcott (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 251–83.

{4} Lawrence Wright, “Captured on Film: Can Dissident Filmmakers Effect Change in Syria?,” New Yorker, May 7, 2006.

{5} Sergey Daney, “Cahiers in Damascus,” in The Cinema House and the World: The Cahiers du Cinéma Years 1962–1981, ed. Patrice Rollet with Jean-Claude Biette and Christophe Manon, trans. Christine Pichini (Cambridge: Semiotext(e), 2022), 442–55. Originally published in Cahiers du Cinéma, nos. 290–91 (July–August 1978). Another response to the events appeared in Abounaddara, “A People Without Cinema—Le Peuple Sans Cinéma,” Facebook, February 4, 2020, last edited March 14, 2021.

{6} Lawrence Wright, “Disillusioned,” in Salti, Insights into Syrian Cinema, 59.

{7} See ch. 1, “The Camera-Eye: Dialectics of a Metaphor,” in William C. Wees, Light Moving in Time: Studies in the Visual Aesthetics of Avant-Garde Film (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 11–30.

{8} Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Boston: Zone Books, 1995). For a broader understanding of how Debord’s thinking is mediated by, and guides, theorizing May 1968, see Andrew Merrifield, Guy Debord (London: Reaktion Books, 2005).

{9} See Helga Tawil-Souri, “It’s Still about the Power of Place,” Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication 5, no. 1 (2012): 86–95; and Hatim El-Hibri, “Arab Revolutions: Breaking Fear: The Cultural Logic of Visibility in the Arab Uprisings,” International Journal of Communication 8 (2014): 835–52.