We, in the City

Yasmin El-Rifae

I wrote most of this essay in my last months in Cairo, before moving away for what felt like the last time. I came to the page to make sense of the alienation and grief I was feeling toward the city, which I was seeing reflected back by people around me. It had everything to do with space, and how it can control time, and how the shapes of both can change us as we live.

How are we resisting an overwhelming present? As a city and a generation still being punished for our past, what does it take to see a future?

****

Summer 2022

My son’s grandmother was nursing him through a fever at her house, a houseboat on the Nile, when a government officer rang at the gate. He had come to deliver papers saying the government was seizing the property, papers he had been delivering to her neighbors over the previous days. She had him come up to the room where my son was convalescing, and told him she could not receive the papers now. Could he come back next week when she’s had a chance to speak with her lawyer? The officer worked for the civilian authority that administers the city’s waterway, and he was apologetic. “They are digging inside of people for money,” he said, as she pressed cold towels to the boy’s hot forehead.

The houseboat is connected by a short wooden bridge to a garden on the riverbank. High trees and children’s swings and interesting birds move between the river and the street. I imagine that my children’s feelings toward the spatial world, and toward atmosphere, are constructed similarly to how mine were as a child: intense, sensuous, almost totalizing. This garden is fun. This house is love. This kitchen is permission. This classroom is restriction. I watch how important it is to them, as they crawl and then as they walk, to map the spaces that they spend time in, to know the different rooms and where all the doors and hallways lead. Learning to play on and against those atmospheres, the codes of each shared space, might be part of growing up, of finding both autonomy and society.

They say there are more cranes in operation in Cairo than in any other city in the world right now. The military is overseeing and in many cases directly executing a city- and nationwide pattern of demolition and construction. The Ministry of Defense has built dozens of bridges and motorways in the last few years, and flattened entire neighborhoods to design and build new ones in their place. Roads and sidewalks are constantly being broken up and repaved and then broken up again. No explanation, no schedules are given to residents, who wake up one day to find a road they have taken all their life is gone. The romantic history of Cairo’s houseboats and the class position of many of their residents raised a certain level of alarm at their destruction. But people in numerous working-class and poor neighborhoods had already been fighting to keep their homes, losing their homes, for years.

Part of the logic behind all this is the integration of the military regime’s new administrative capital, under construction twenty-eight miles to the east, from which it hopes to reap significant profit as well as symbolic capital. A gated, controlled space where everyone has been security-checked is to become the new political and administrative heart of Cairo. A new capital for a new Egypt. In 2020, a hashtag appeared on television stations: #NewRepublic2030. The future is framed as a departure, and the vision of change is to build mirror cities alongside those that already exist, to be filled by people plugged into new networks of debt. This destruction and redrawing of space, the erasure of our knowledge of it, is connected to how we lose ways of speaking to one another, of seeing one another.

Moving from one Cairo neighborhood to another today carries a risk of confoundment and of getting lost, even to the most seasoned commuter. To get from one neighborhood in the center to one in the east—from, say, Imbaba to Heliopolis—your GPS is likely to take you far out into the desert, onto the smooth new concrete roads, and back in again. We lose our way through the city.

Every few months, I bump into an artist I know and like. We have a conversation that feels like it could go on forever. Most recently, we were at a mutual friend’s exhibition. This friend is fighting a particularly deadly form of cancer, and doing so with verve, a summoning of the life forces of making and sharing space, food, and art.

This other artist and I were talking about Cairo’s changed social rhythms. Everything feels smaller. People don’t see each other as much anymore. Was it just us? Were we just getting older? Was it the pandemic? “I think it’s a longer arc than the pandemic,” she said. “There are no more spaces for people to gather, nothing to bring us to one another. And it’s become so hard to move. People stick to the two or three others they’re close to, and that’s it.” The broad and differentiated networks that joined up in the revolution of 2011 have now dispersed into these smaller, more isolated groups surviving together.

For many of my generation in Cairo, public space appeared for the first time during the revolution. The city had long neglected public space, and police states like Hosni Mubarak’s functioned by restricting people’s abilities to use or make it. During the mass uprising against Mubarak in 2011, public space opened up like another dimension, changing our relations to the city and to one another, unleashing multiple horizons of political and social possibility. Two years later, the military couped the Muslim Brotherhood government out of elected office and massacred hundreds of protesters camped in two public squares. As intended, these acts of violence ensured that very few people would fight for public and political space in the years to follow.

On state-controlled television talk shows, they say that only commercial houseboats will be allowed to stay on the river. They accuse residents of being selfish for wanting to live in this way, privately enjoying the nation’s most symbolic natural resource. A government spokesperson invites the owners to apply for commercial licenses—at exorbitant fees—so that they can keep their property. You can keep your home so long as it’s no longer a home. In the government’s doublespeak, public space means commercial space.

The military is now a major player in Egypt’s food and beverage service economy, running multiple coffee shop and restaurant franchises. Its cafés are lined up underneath the new concrete bridges within and around the city. When you drive on these bridges in an Uber or a private car, and on the highways that connect to gated, suburban compounds, there can be a sense of timelessness. This desert could be any desert, this sunset any day’s. It’s on the street level below that we find friction, and time.

Cairo’s café culture has also come to include dozens of top-grade espresso chains, and the type of hipster café that one can find in any of the cities where you’re probably reading this essay. In these cafés, I’m in a version of a globalized time: the supply chains, the drinks themselves (flat white, oat milk latte), and the aesthetics are globally linked. A latte in a paper cup can cost almost half the daily wage of the nanny who takes care of my children.

My paper coffee cup is among a newer batch of class signifiers worn by pedestrians in neighborhoods where the rich still occasionally encounter the poor on sidewalks: yoga pants, expensive water bottles, expensive headphones. The cup tells others on the street around me something about my life at the same time it helps me keep my attention focused on myself as I walk. Confronting human desperation has always been a part of life in Cairo, but it has never been so easy to ignore. Billboards advertising the new capital and other gated communities hang over our heads like a question, or an inevitability.

In Susan Buck-Morss’s reading of Walter Benjamin’s work on aesthetics, she argues that Benjamin returns us to the classical philosophical definition of the Greek word aisthesis, meaning perception through the senses. Under this notion of aesthetics, the sensorium and the interpretation of the world through it can be considered a place of thought.{1} For Benjamin, modernity is experienced as a series of shocks (the shock of the battlefield, the shock of the urban street). One of the ways the individual copes with these shocks is by blocking them out. When we stop taking the world in and responding to it, the sensorium becomes a place of numbness rather than perception, of anesthesia instead of aesthesis. When this happens, Buck-Morss writes, it “destroys the human organism’s power to respond politically even when self-preservation is at stake.”{2} What does it mean to live together in a city in which we are unable to see or hear one another?

Many of my generation are incarcerated, and so we must ask about prison as a space that is part of the city even as its very purpose is not to be.{3} As I write this, the political activist and writer Alaa Abdelfattah is in his third month of a hunger strike in jail. He has spent most of the last decade in prison, held there through the death of his father, a leading human rights lawyer and a torture survivor, and the birth of his own son, who will soon no longer be a child. Alaa is also my partner’s cousin, and we began a friendship in the brief time he spent out of prison in 2019. Alaa might be dead by the time this essay is published, but his life in prison has already been conditioned by the death forces that deprive him of human contact, of reading, and of fresh air. His hunger strike asks: What becomes of the human sensorium when it’s denied sunlight or reading?{4} What does it mean to preserve your life when you are being subjugated to the “power of death”?{5} Does Alaa survive only by turning to the negative of biological preservation? Or is it by embracing death that he can truly struggle for life?

The politics of the hunger strike works by redrawing the list of possible futures. If he dies in prison, it will not be because they kept him there for the course of his biological life. The only other real outcome—the one his hunger strike strives for—is his release into exile.

Alaa is sometimes called the voice of a generation because he wrote and posted so prolifically, and because his idea of politics is that it must include those who are different from him. He spoke about Islamists and communists and socialists and . . . No freedom for me, unless there is freedom for you and for all of us.

It’s the internet that allowed him this voice, first as a blogger in the mid-2000s, just as it’s the internet that gives the regime legal cover for keeping him in jail now for sharing a Facebook post. (The judge wasn’t present in the courtroom for the sentencing, but that’s another theater.) It’s on the internet that his friends try to speak now, to save his life. His body is absent, but as the weeks and months go by, we still know about it, about its diminishment, its starvation, its continuation. We cannot see his striking body, but we are still its witnesses.

****

Alaa’s hunger strike will continue for nine months and end after a six-day water strike coinciding with the Conference of the Parties—the UN’s meeting on climate change—in Egypt in November 2022. His strike and the campaign around it will change the conversations at that conference, will change the global headlines: his body will become the ground, the stakes, the departure point for discourse. The argument it is making is that we cannot talk about the future of the planet without talking about the future of life on the planet, of what we do to one another’s lives and bodies.

Meanwhile, in his thirst and frustration with his jailers, Alaa will bash his head against a wall until it draws blood. Sometime after that, he will turn away from death, and his cellmates will hold his body and save his life.

The world will find out this information weeks after it happens. For his supporters, who had created a global solidarity campaign, his account will be harsh, devastating. Through the time of the strike we knew about but could not see, we had split him into two presences: that of his weakening, starving body, and that of his steadfast, thinking mind. We had forgotten that the body, its senses, its spatial existence, can and sometimes must take over the mind, any mind.

After he ends his strike, Alaa’s jailers will allow him music for the first time in three years. Speaking through a receiver and a thick glass barrier, he will tell his aunt that he felt his life come back to his limbs as he listened to a particular song he loved.

Forces of life and death transcend the physical. Music and art are forces of life; connection is a force of life. Our thinking bodies need them. Enforcers of violence—in prisons and in the city being destroyed—know this. They know it in the sense that they live with and use this knowledge. People paying attention to children know this too.

Is the hunger strike a form of suicide? Two people I knew from leftist circles took their own lives shortly before I wrote this essay. Suicide immediately asks us about the past: What we knew of the person, of their struggles. What we last said to them, what we last heard. It asks us what we could have done. It can be an invocation to action directed at us long afterward, as the memory of Sara Hijazi still is now, two years after her death. Beyond How do we survive this regime, this political era? the suicides can make us ask, How do we keep one another alive?

The hunger strike forces us to reckon with the prisoner’s death as a possibility that is still to come, and so the invocation is all the more direct. To change what it is we are witnessing, to change the story. But in order to do so, we must be able to tell it.

****

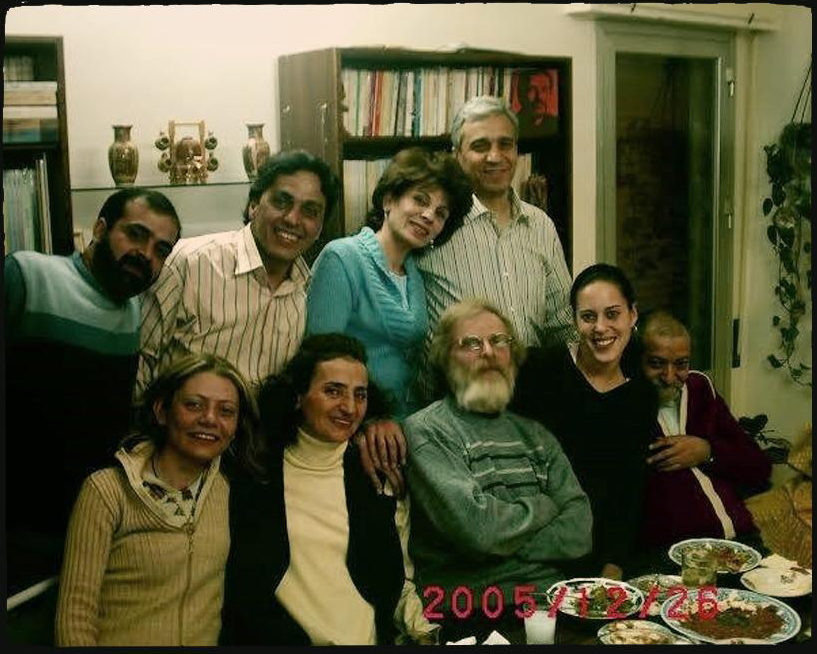

In an essay for Al-Jumhuriya published in 2022, Yassin al-Haj Saleh writes about the act of witnessing and the act of martyrdom.{6} Both are wrapped up in the same word in Arabic, shahīd. In the essay, he examines photographs of himself with a group of friends one evening in Damascus in 2005. One by one, he tells us who these friends are, the kind of shahīd they have been—martyr or witness—and what we know of where they are now. From the photographs of men and women smiling, dancing, embracing, and goofing around he relays a calculus of murder and kidnapping, of years spent in prison, in exile. Each event is world-shattering in its particularity, but here, layered onto each other, the events create a slower story, a context, a lifeworld. From the photos, too, he tells of each friend’s life—insists on it.

Quoting Agamben, al-Haj Saleh talks about the act of witnessing in connection to life and death. The living can never be complete witnesses, because they have not seen everything. Those who have seen more—those who have been disappeared, those whose status of life or death is uncertain—are confined to a separate, isolated space, in order to prevent them from saying what they have witnessed. This tells us, al-Haj Saleh writes, that the criminals who have subjected life to death know they are criminals, and that only the dead—the martyrs—have seen everything. They cannot give their account, and so we the living, who have witnessed part of their stories, must give our own. The account will never be complete, but it will be more just.

Al-Haj Saleh gives his account and writes so prolifically because he insists on being a witness, despite the harshness of these scenes. In fact, it’s the harshness itself that he examines. He tells us how, as politics spiraled into wider repression and violence in Syria, his friends and comrades retreated into their private spaces, into their own and one another’s homes. “We tried to live normal lives in our homes, but in the end, this was impossible,” he writes at the end of the piece. “A normal life requires a normal public life; that is, a normal life for all.”

In Cairo, I shared al-Haj Saleh’s piece on a family chat, and the eldest among us replied, “The continuum.”

I sense in myself and in the community around me a disorientation in both time and space. The physical changes to the city around us are relentless, often executed very fast, and they have long-lasting, perhaps irreversible effects. It is hard to keep up with the present, and the future feels like it is being shaped, necessarily, without our active participation. Simultaneously, we remain the generation of the revolution, and we remember or understand what it was for time to stand still, just as we understand that the futures we glimpsed then are lost forever. We feel slow, ineffective, forever having to confront our political defeat. There is a psychic pain in these schisms, in trying to live with—and in trying to resist—these two senses of time, the fast time of the state project and the slow time resulting from our own generational experience. Importantly, both senses of time are without a future, and therefore without hope.

Yassin al-Haj Saleh, “سِيَرٌ سوريّة في صورة: مَن الشاهد؟” [Syrian stories in a photograph: Who is the witness?], AL-JUMHURIYA, February 14, 2022.

Yassin al-Haj Saleh, “سِيَرٌ سوريّة في صورة: مَن الشاهد؟” [Syrian stories in a photograph: Who is the witness?], AL-JUMHURIYA, February 14, 2022.

A few projects—newspapers, art collectives, human and civil rights groups—allow us to live a different kind of time. These require that people come together, and in that togetherness it becomes both safer and more dangerous to come off the anesthesia, to examine the harshness, to try and understand it, and ultimately to think beyond it: to think about the future as a changeable horizon. As we live under a constant threat from the state, the psychological stakes of this alertness are high. Independent collectives and institutions that have survived waves of crackdowns have done so at a cost, and have been shaped by each one: the ways people relate to one another has been shaped by each one. We speak of resilience and perseverance, but we don’t often speak about the cost on ourselves and our relationships as an ongoing part of life in these spaces.

In this context, the spatial disruption that came with the pandemic was devastating. But in the aftermaths of both the coup and COVID-19, I could trace the ways that people were redrawing the private sphere both to settle in and to find ways out: living together differently, organizing private reading groups and collective projects, or dedicating themselves, alongside activism, writing, and filmmaking, to bodily practices like dancing, rowing, cycling, and climbing. As though something in our inability to move through the city finds an outlet, a re-creation, in the repetition of these physical activities.

Al-Haj Saleh is right to point to the limit of dividing the private from a devastating public life, but at what point is the private also able to change the public in a meaningful way, whether through the discursive work it produces, or through the ways that the people making the work are living, the smaller worlds they create? For those of us trying to do political work, how do we negotiate this necessary permeability when the city forces us to withdraw in order to survive?

****

In our last few days on the boat, before they take it away, the deck is full of people coming by to help us pack, to think about how we might try and save the boat, or just to look out at the river with the knowledge that this is a vanishing perspective. Among the Egyptian Left, solidarity—togetherness—comes in gathering at funerals, or at court, or at a house or office when the police knock on the door, or when suicide is invoked. Solidarity remains during those moments when our presence in the world is directly threatened, when the line between life and death trembles. Here we are sharing a shock, we are extending and opening out to one another, to experience it together, to be in time together. This is a solidarity of survival, completely necessary even as it is shaped, in part, by historical defeat.

Months later, I will meet a friend from Palestine, who also recently left her difficult city. She tells me that her group chats with friends at home are silent when Israel kills but erupt with conversation when there is an act of resistance. I remember the collective electricity that ran through us in Cairo when six Palestinian prisoners dug their way out of their cells with a spoon two years ago. They were eventually recaptured, but for us witnessing it, it was a sudden horizon through the concrete, a horizon we could share. Such a horizon is long, made and remade over time, and the longer you look at it, the more it might tell you about your stakes in it. For Palestinians, the stakes were clear from the moment of catastrophe: your home, your life, your existence in this place. For my generation in Egypt, we are learning these stakes through our lived experience, perhaps in the widest, clearest way yet. As much as I had intellectually understood that Egypt’s future was bound up in Palestine’s, I had never truly thought my home could be taken away, that I might live and raise children with the experience of what that felt like. This is a different knowledge: foundational, unabstracted, unspectral.

The horizon has to widen in order to be seen at all.

****

London, 2023

It’s winter now. In line with a new IMF grant, the Egyptian government floated the pound a few days ago, and it lost a further 50 percent of its value overnight. The economic collapse that has been off-loaded onto the poor for years already through the canceling of subsidies on food and energy has now arrived for the rest.

I write a message to a close friend to ask how she is in the aftershock. I’m unsure of my choice of words and I hesitate before I send the text; I’m still getting used to communicating with her from this distance. She calls me a couple of minutes later. We talk about the end of middle-class affordances (life savings are now worthless, the prospect of buying a home has gone from real to nil). “It feels very unstable, politically, but I think we might be in this instability for a while,” she says. I look at the bare trees outside the window as we talk, and I think that my generation’s feeling of being in constant crisis is also part of something larger, something cyclical. There is little solace in that, just as there’s little comfort in recognizing that the revolutionary past remains both with us, we who had hoped within it, and with those who now rule on the basis of eliminating its repetition.

Of course nothing actually repeats itself, in the true sense of the word.

Now that my son has adjusted to the new spaces and rhythms around him, is less consumed by their novelty, he is speaking more about Cairo, and of course about the houseboat. He will not see it again, at least not as it was. But it has made its spaces in him already, and it—and the loss of it, its absence—will be one of the stories of his life. A time and space he witnessed. A time and space that will ask its own questions.

Title video: Photographs by Omar Elkafrawy.

{1} Susan Buck-Morss, “Aesthetics and Anaesthetics: Walter Benjamin’s Artwork Essay Reconsidered,” October 62 (Autumn 1992): 6.

{2} Buck-Morss, “Aesthetics and Anaesthetics,” 18.

{3} The number most often quoted from a few years ago counts at least sixty thousand political prisoners. Among the state’s construction projects is the new Wadi El Natroun correctional facility, which it has advertised on television as “an American-style prison.”

{4} For more than two years, Alaa was not allowed his right to access books or take his daily exercise time outside of his prison cell. In June 2021, in his third month of hunger strike, he was moved to a different prison and his conditions improved.

{5} On the “power of death,” see Achille Mbembe, “Necropolitics,” trans. Libby Meintjes, Public Culture 15, no. 1 (Winter 2003): 11–40.

{6} Yassin al-Haj Saleh, “سِيَرٌ سوريّة في صورة: مَن الشاهد؟” [Syrian stories in a photograph: Who is the witness?], Al-Jumhuriya, February 14, 2022. Translation by the author.