Recovering Histories of Struggle and Solidarity with Kristine Khouri and Rasha Salti

Kareem Estefan

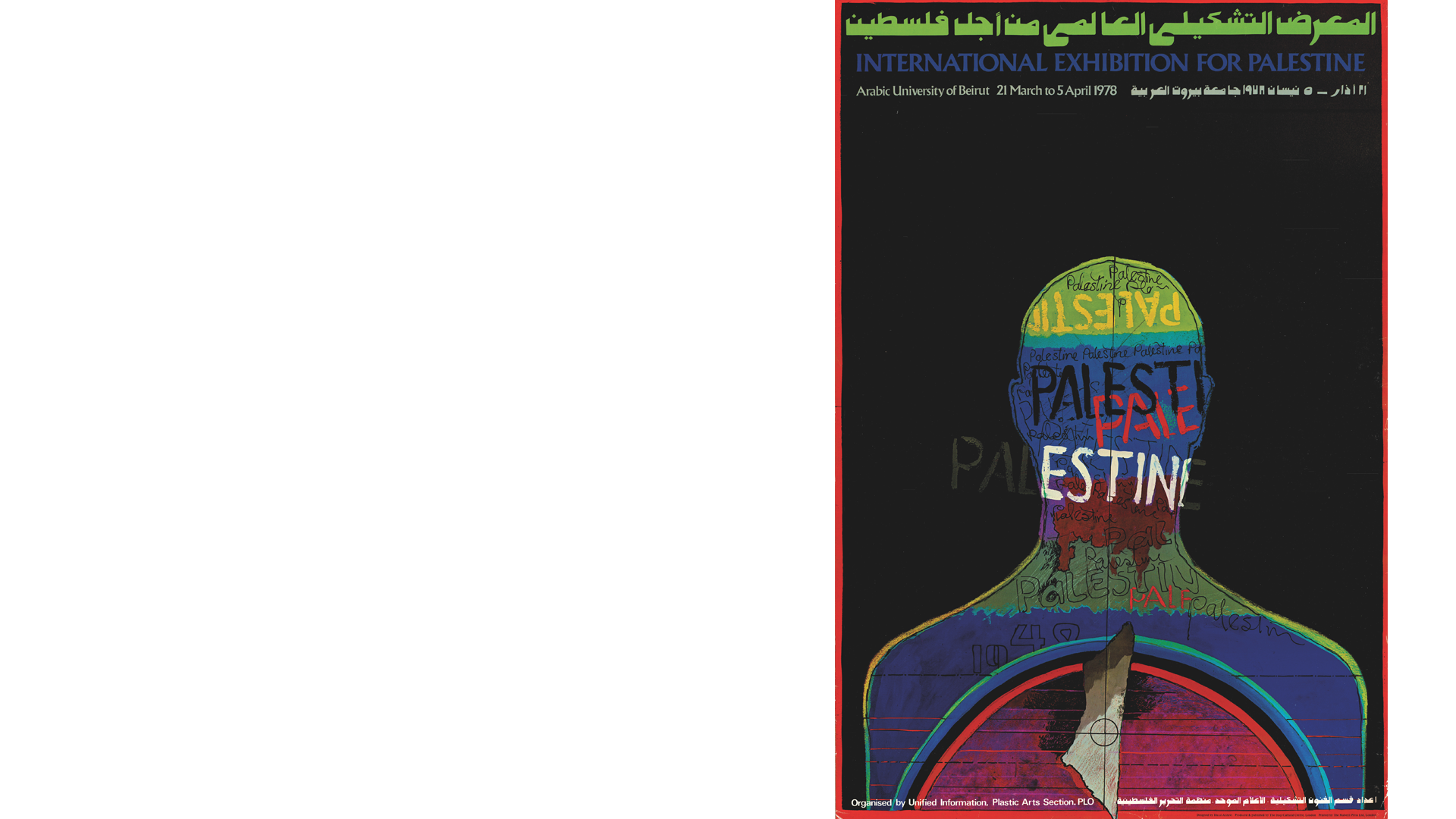

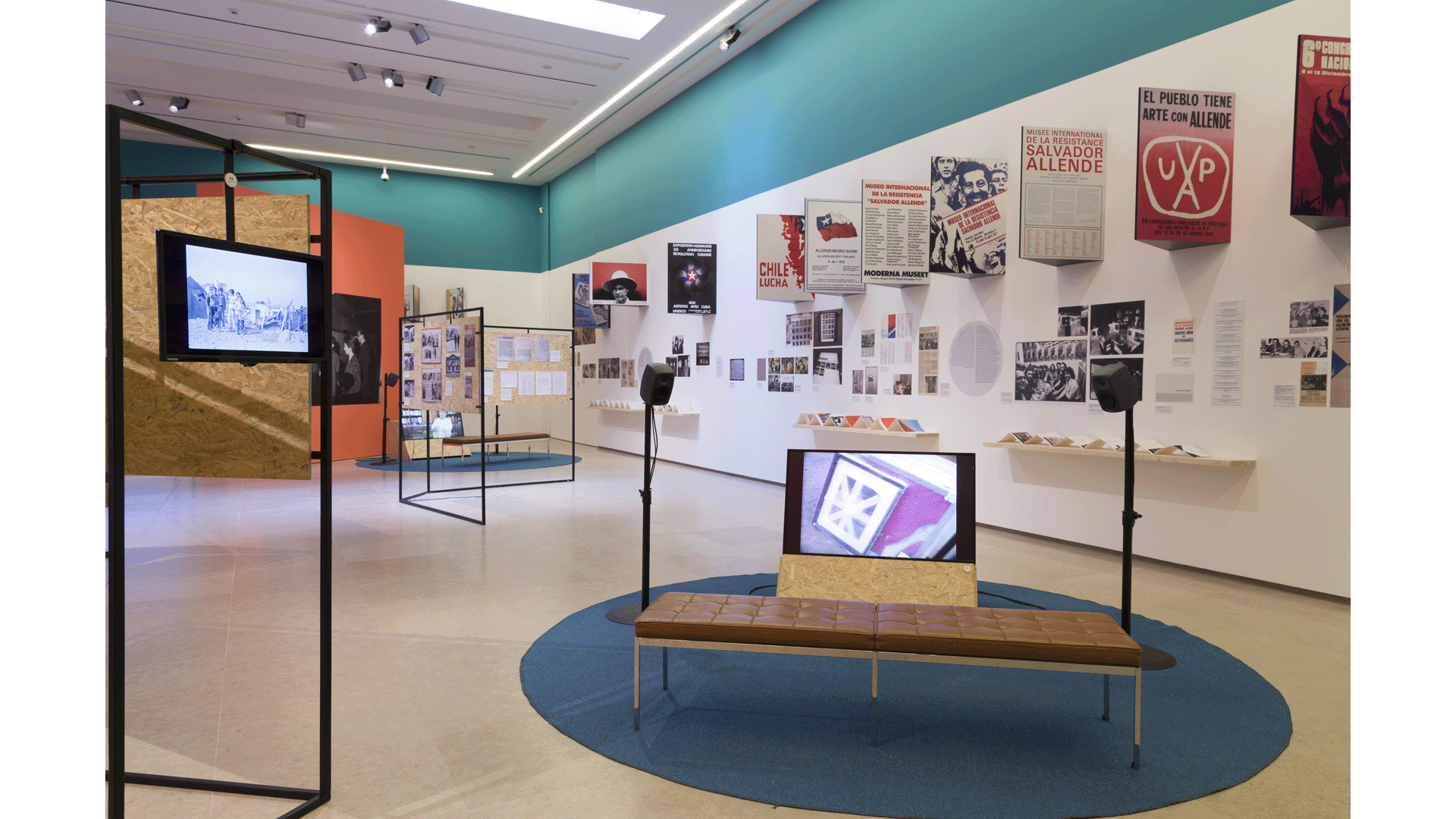

In 1978, the Plastic Arts Section of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) organized the International Art Exhibition for Palestine in Beirut, the city that then served as its base and a kind of extraterritorial Palestinian capital. This substantial exhibition of artworks—donated to the Palestinian people by nearly two hundred artists from thirty countries around the world, in anticipation of a Palestinian museum in a future Palestinian state—was unknown to curators Kristine Khouri and Rasha Salti when they chanced upon the exhibition catalog at a Beirut art gallery in 2008. It became the foundation for their remarkable exhibition Past Disquiet, which recovers artworks and documents related to the 1978 exhibition alongside materials from three other museums-in-exile inaugurated in the 1970s and 1980s: the Museo Internacional de la Resistencia Salvador Allende, Art for the People of Nicaragua, and Art Contre/Against Apartheid. Like the exhibitions it documents, Past Disquiet has itself been itinerant and global, traveling from Barcelona to Berlin, Beirut, and Warsaw since its first iteration opened at the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona in 2015.

Drawing on years of research into the many international artists and activists who contributed to these projects, Past Disquiet reactivates an era of transnational struggle and solidarity in which Palestine was a central node. In the context of the ongoing Palestinian liberation struggle, then, Khouri and Salti’s exhibition is a time capsule that transports contemporary audiences back to a moment when a robust, militant Palestinian national movement found comrades in an international Left forged through the Non-Aligned Movement, the fight against South African apartheid, and anticolonial and socialist revolutions from Algeria to Nicaragua. Past Disquiet indexes a period of thawra (revolution) that many younger Palestinian cultural producers are revisiting today, seventy-five years after the Nakba (or “catastrophe,” referring to the Zionist dispossessions that established the State of Israel in 1948) and amid an ever-worsening situation of ongoing colonization and occupation, ascendant Jewish-supremacist politics within Israel, corrupt and complicit rule by Palestinian elites, and continued enablement and inaction from the “international community.” With this in mind, I asked Khouri and Salti a series of questions about the ways that Past Disquiet not only tracks transnational solidarities, but also opens transgenerational horizons for the Palestinian struggle. How and to what extent do young Palestinians—and people acting in solidarity with Palestine—remember the distinct histories showcased in Past Disquiet? What do a previous generation’s political experiences and orientations mean for a younger generation? Is it possible, or desirable, to recuperate and reanimate features of the erstwhile Palestinian national movement and its international dimensions today?

****

Kareem Estefan

Past Disquiet reconstructs cultural histories of international solidarity with Palestine. How has the nature of the networks of solidarity documented by the exhibition changed between the 1970s and today?

Rasha Salti

Past Disquiet revisits stories of four museums attached to four cardinal struggles at the heart of the international solidarity movement of the 1970s. Let me begin by considering, for a minute, where these struggles stand today. In Chile, Pinochet was expelled from government with a national plebiscite in 1990, but the toxic legacy of his regime endures, for example, in the constitution that vibrant social movements and a young leftist president are fighting to rewrite. In South Africa, Nelson Mandela was released in 1990, and the apartheid regime was formally put to an end. A new constitution was promulgated, and yet thirty years of African National Congress rule have not reversed the legacy of racial segregation. In Nicaragua, the Sandinista movement is today synonymous with an autocratic, corrupt, and repressive party that refuses to relinquish power. In occupied Palestine, the proto-state structure of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) has devoured the PLO, previously a diasporic political entity headquartered in host Arab countries, namely Lebanon (1969–82) and Tunisia (1982–93). The PNA is widely discredited because of its subservience to the Israeli state. Today it is far more efficient at policing Palestinian citizens than at securing their well-being and sovereignty.

These changes have unfolded in the context of an entirely different world. The Cold War is over—or perhaps I should say that the First Cold War is over, as the Russian war on Ukraine in many ways heralds a Second Cold War. The bipolar tension that characterized the Cold War until 1990 was replaced with unilateral US imperial hegemony. The Non-Aligned Movement and its residual formations have also lapsed. International solidarity is manifest today largely across leaderless mass movements, from alter-globalization currents visible in the anti-WTO protests in Seattle in 1999, to antiwar coalitions such as those demonstrating against the US occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan, to Black Lives Matter, to take a few examples. The fact that these insurgent dissenting movements are the outcome of a wide and heterogeneous horizontal network of alliances, comprised of citizens and intentionally leaderless, imparts specific paradigms and conditions for weaving transnational solidarities.

If we are to consider how the structure(s) and expression(s) of international solidarity manifest today, it is crucial to acknowledge that they operate from a foundation of fragmentary memory. This is reflected in our attempt, with Past Disquiet, to reconstruct the story of a fantastic and awe-inspiring undertaking: the planning of a museum of international contemporary art that would incarnate the righteousness of the Palestinians’ cause through donations of artworks. Such reconstruction was necessary, in the first place, because the story (or stories) of this museum was not recorded and transmitted to subsequent generations.

Kristine Khouri

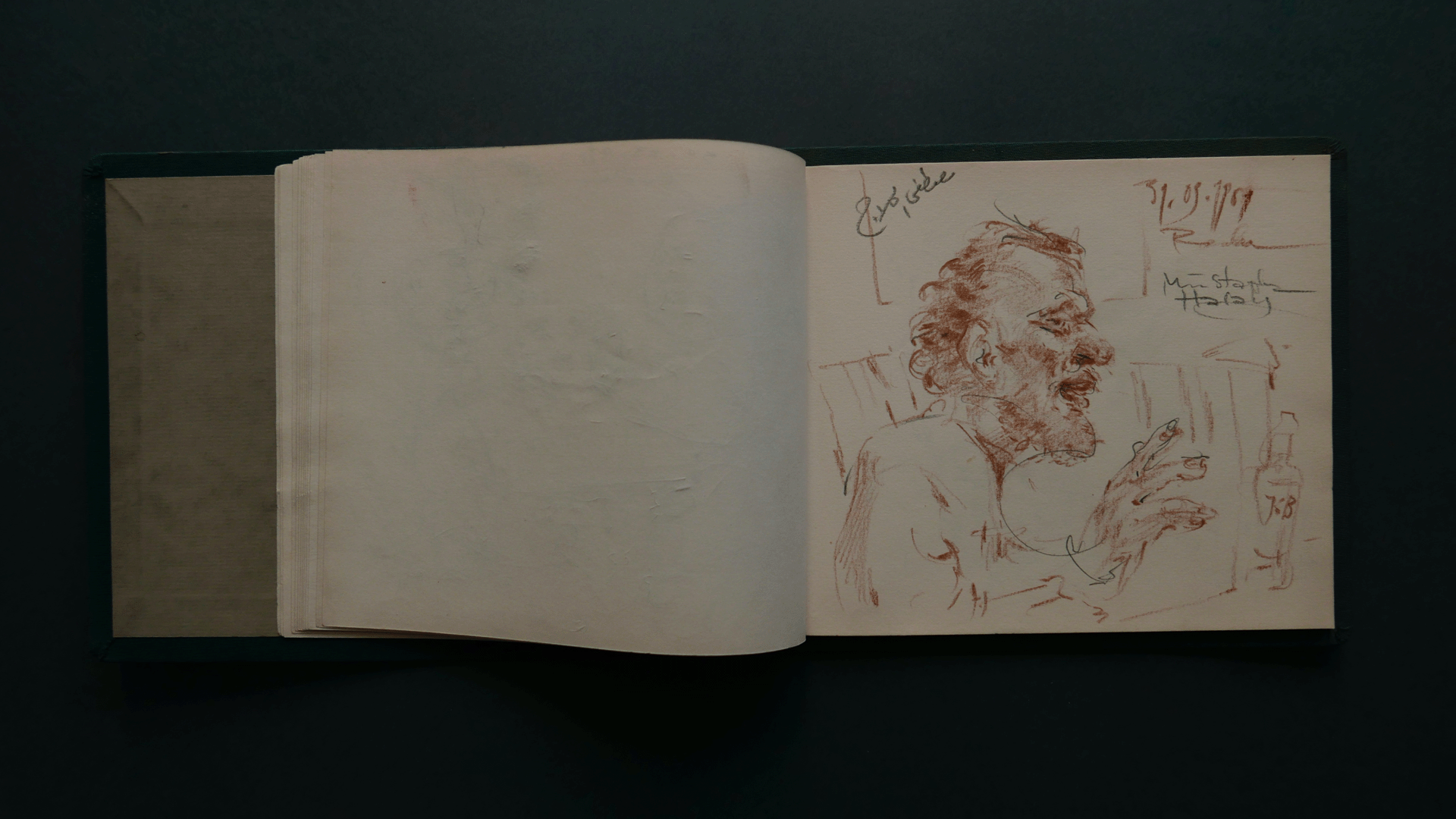

Past Disquiet documents a history of transnational exchanges, facilitated in a myriad of ways, in which artists, writers, and filmmakers traveled to witness the Palestinian revolution and experienced firsthand the living conditions in refugee camps. In a few cases, artist unions collaborated to make this happen, and in the case of the Union of Palestinian Artists, the trip was facilitated by political entities, namely the PLO. In the case of the GDR, artists belonging to the Union of Visual Artists traveled to Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan in 1979 and 1981. They took photos, made sketches, and eventually produced artworks inspired by the trips. One artist, Günther Rechn, chronicled Lebanese and Palestinian artists he met, as well as political figures, in a sketchbook. While official trips of this sort can be read as propagandistic, these visits were transformative for many of the artists. Upon their return in 1981, they exhibited the resulting artworks in Beirut and in Cottbus (Germany) under the title Engagement Palästina, with support from the Ministry for Culture of the GDR and the Union of Visual Artists of the GDR. Another example is that of five artists who came to Lebanon from France and Italy ahead of the opening of the International Art Exhibition for Palestine and organized a collective workshop with local artists, facilitated by the PLO’s Plastic Arts Section. An open-air exhibition of the art produced at the workshop was mounted in May 1978, on the same campus that the International Art Exhibition had been held. In Past Disquiet, photographs that document dinners, camp visits, trips to southern Lebanon to meet fighters, and of course exhibition openings, coupled with interviews with a few of the artists, illustrate how the artists’ engagement with the Palestinian struggle transformed after their visits.

Learning from the histories and transnational undertakings that Past Disquiet activates can be inspirational in reimagining what collaborations look like. For example, the exhibition offers ideas about how museums and other institutions can engage with and offer platforms to collectives and movements, and challenge traditional north-south relationships and power dynamics. Personally, I hope that it also provokes questions about solidarity, including how existing institutions or collections can take stronger positions in their programming, how they acquire (or refuse to acquire) work, and how they collaborate with others.

KE

How widely was the memory of the 1978 International Art Exhibition for Palestine, and the broader period of Palestinian solidarity with other Third World struggles (and vice versa), passed on to the next generation? In your research for Past Disquiet, were you always speaking with artists, filmmakers, militants who were active during that period? Or were there younger people who had inherited those memories and memorabilia?

KK

We were primarily speaking to people who were active during that period, but also to researchers, curators, and artists from a younger generation. Among this generation, some had inherited the history but many had not, unless their parents, for example, were implicated in the history. I would say that, in many cases, the knowledge of the transnational relationships was not necessarily passed on. As for the memory of the 1978 International Art Exhibition for Palestine in Beirut, it especially didn’t seem to be transferred; the younger generation was familiar with the work of artists, filmmakers, and others who were active at the time, but not necessarily with the specific institutional and exhibition histories. The lack of knowledge transfer about the other kinds of work people did—for example, in organizing—is quite evident. What remains, if we’re lucky, may be the artwork, poster, or publication itself but not the history of its container: where it was shown, or information about who organized it and imagined it.

RS

We interviewed cultural actors as well as militants, political cadres who occupied important posts in the PLO hierarchy. Past Disquiet attempts to unearth unwritten histories for Palestinians, Chileans, and South Africans, as well as Italians, French, Hungarians, and Japanese. Our interviewees ranged from forty to ninety years old. The younger ones were bequeathed memories and memorabilia to carry forward their elders’ political commitments.

Photograph from Mostra Palestina, organized by the Italian collective L’Arcicoda, with a collective hanging mural done with the Collectif Palestine of the Jeune Peinture, in San Giovanni Valdarno, Italy, 1976. Image courtesy of Sergio Traquandi.

Photograph from Mostra Palestina, organized by the Italian collective L’Arcicoda, with a collective hanging mural done with the Collectif Palestine of the Jeune Peinture, in San Giovanni Valdarno, Italy, 1976. Image courtesy of Sergio Traquandi.

Opening of the INTERNATIONAL ART EXHIBITION FOR PALESTINE, Beirut Arab University, March 1978.

Opening of the INTERNATIONAL ART EXHIBITION FOR PALESTINE, Beirut Arab University, March 1978.

Exhibition view of May 15 Exhibition, Day of the Palestinian Struggle, at the courtyard of the Beirut Arab University, 1978.

Exhibition view of May 15 Exhibition, Day of the Palestinian Struggle, at the courtyard of the Beirut Arab University, 1978.

KE

How would you describe the generational divides—and overlaps—that exist among Palestinians? Often one hears of a “Nakba generation” and a “Thawra generation,” for example. Do these terms mark moments of deep rupture in the Palestinian experience?

RS

It was only while working on Past Disquiet that I became aware of the peculiar significance of revolution for the generation that led the struggle in the 1960s and 1970s, or in other words, of the divide in consciousness, subjectivity, and political agency between what you describe as the “Nakba generation” and the “Thawra generation.” In fact, it’s interesting that you use thawra in reference to that generation to begin with, because for those who were in their twenties, thirties, or forties when the Nakba happened, their parents who participated in or witnessed the Great Revolt of 1936 were the Thawra generation. The grandparents had risen against the British colonial administration and its complacency with the increasing Jewish settlements in Palestine.

The Great Revolt ended in 1939 after a violent retaliation from the British. It was a humiliating defeat, but the insurgents were proven right. Less than ten years later, the Nakba happened. In that very quick chronological sketch of a generational continuum, those who became refugees when they were children or teenagers—and whom I consider to be the “sons”—those who were bequeathed the compounded trauma of defeat in 1936 and expulsion in 1948, are those who decided to recreate political bodies, in spite of material and immaterial loss and dispersal. In the mid-1950s, the “sons and daughters” created the General Union of Palestinian Students across the world, and a decade later they founded the PLO. This I perceive as a different kind of revolution because it is a reclaiming of political agency from the perspective of a refugee that fundamentally rejects the rules of being a “guest” in a host country. While the Nakba generation—the “parents”—were struggling to secure a modicum of survival for their families within the boundaries of what they were allowed to do, their children rose up, risking to shatter the rules of the game, to reject living in indignity. That founding generation of militants, who peopled the PLO, trained in armed combat, actively engaged in legitimizing their right to exist and to return to their homeland, were refugees stripped of most of their basic rights, and they carried that double trauma. Changing the rules that codified their being in the world as refugees, or as guests with regard to host regimes, necessitated mobilizing empathy and forging alliances.

KE

It’s common to map generational ruptures onto technological ruptures, but have artists, filmmakers, or activists managed to collaborate on cultural projects that span technological and generational divides? And how are contemporary artists—younger Palestinians as well as those making work in solidarity with Palestine, after the period covered by Past Disquiet—engaging these histories?

RS

In general, I am always suspicious of notions of “generational divide” and “rupture” because when the production of knowledge about the arts is primarily driven by the logic of the market—as it is nowadays—these motifs invariably come up, alongside the oedipal urge to kill the father. The market thrives on the dramaturgies of rupture and killing the father.

The reality of the dispersal of Palestinians, between the diaspora, the refugee camps, enduring military occupation in the West Bank and Gaza, and the toxic duality of being “Arab-Israeli,” makes the transmission of memory, knowledge, aesthetics, and poetics extremely complicated. To make matters worse, the archival and documentary traces of the “Lebanon chapter,” or when the PLO was based in Beirut (1969–82), were either destroyed or stolen. When the Israeli tanks rolled into Beirut, they targeted PLO offices and research centers, piled content into trucks, and blew up the buildings. The Israeli army gave back some of the looted archives, but only a fraction. For Palestinians living under military occupation, keeping documents and archives was judiciously avoided lest military administrators found evidence to imprison or expel anyone. Past Disquiet relies mostly on the testimonies and the eclectic private archives of those who had played a role in the production of culture.

To cut a long story short: Is there a generational divide? The younger generations are as motivated to preserve the memory and histories of their predecessors as the latter were to preserve the know-how, arts, crafts, and histories of the pre-Nakba generation. Younger artists use another language, other media, and they exhibit their work, seek resources for funding, and relate to the market in a different way. Also, they have not balked at forging their own subjectivities. None of this signifies enmity or even animosity. Obviously, I am referring to general trends; there certainly are cases that exemplify the contrary.

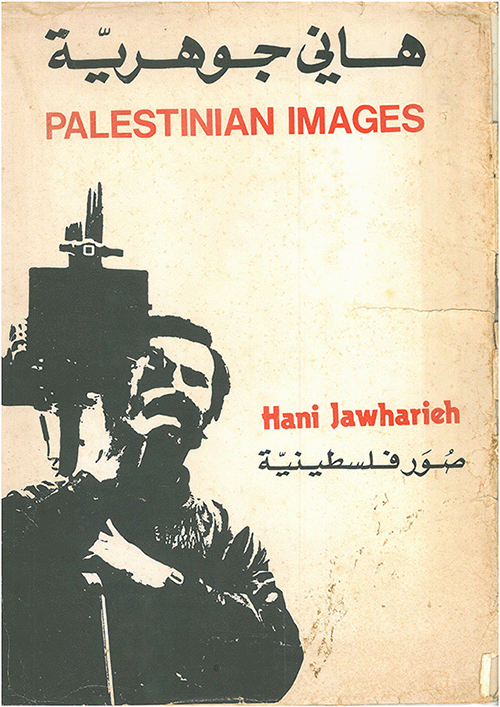

Cover of portfolio titled PALESTINIAN IMAGES, published by the Palestinian Cinema Institute. Courtesy of Rasha Salti.

Cover of portfolio titled PALESTINIAN IMAGES, published by the Palestinian Cinema Institute. Courtesy of Rasha Salti.

KK

There is a lot of work to recover and relate histories of the Middle East and specifically Palestine being undertaken today by younger cultural producers, be they artists, filmmakers, or academics, working independently or through civil society projects. In cinema, the research and production collective Subversive Film (cofounded by Nick Denes, Reem Shilleh, and Mohanad Yaqubi) preserves and creatively engages historic Palestinian films, including many that were produced during the PLO period—and looted by the Israeli army during its 1982 invasion of Lebanon. Filmmakers and artists including Azza El-Hassan, Annemarie Jacir, Emily Jacir, and Monica Maurer have also restored and made work about Palestinian cinema from this era. Many cultural initiatives gather, preserve, and share the histories that Rasha mentions through the development and digitization of archives; some notable examples include projects by the Jerusalem-based Khazaaen, by the Palestinian Museum in Birzeit, and by the Palestinian Oral History Archive at the American University of Beirut, which showcases two archives of recorded testimonials from the Nakba generation. Projects like Palestine Open Maps create an interactive space for memory and storytelling through the digital layering of historical maps. Palestinian artists like Emily Jacir draw viewers into histories of events and moments that have been actively hidden or erased, while more speculative works by artists such as Khalil Rabah, Larissa Sansour, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, and Yazan Khalili offer new ways to imagine a future or past for Palestine, incorporating intergenerational memories while cultivating different narrative possibilities.

KE

How do historical ruptures specific to Palestine, such as the Nakba, the Naksa (the 1967 war or “setback”), the Thawra, the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the first intifada, or the Oslo Accords, intersect with historical shifts at a global level? I’m thinking, for example, of the simultaneity of struggles in Vietnam or South Africa, their passing, and later the fall of the Soviet Union. What do these interconnections mean for the question of generations?

RS

You are right to raise the question of the concomitance, or contemporaneity, of anticolonial and anti-imperialist liberation struggles. Certainly, it is easy to identify resonances between the plight of Palestinians and that of others whose right to self-determination was denied by the major world powers. Furthermore, as a settler colony, the State of Israel used overtly colonialist language, discourse, and methods of counterinsurgency. However, the genius of the generation that founded the PLO is to have succeeded in presenting Palestine as a metaphor for the world’s injustice. This was accomplished by the patient, concerted work of militants worldwide at the grassroots level, and by the brilliant and eloquent work of poets, writers, artists, filmmakers, and intellectuals. This is the reason that studying the Palestinian poster production until the Oslo Accords implies looking at posters made by Palestinian artists as well as Arab and international artists. The case is similar with film.

To think more generally about the anticolonial consciousness of Palestinians, the Nakba was the outcome of a war that erupted when Palestinians rejected the partition plan that the British colonial administration proposed as a solution to end their mandate, through the establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state and a sovereign Jewish state. The British also proposed partition plans for ending their colonization of India (thus creating two states, India and Pakistan) and of South Africa. In all three situations, partition produced war, strife, violence, and indignity. The blood-drenched legacy of enduring British colonialism was also one of the elements that nurtured a kinship, or resonance, for forging solidarity. There is much more to say on this subject, but Palestine’s relationship to South Africa is particularly potent and worth exploring in relation to our present moment, as the ideologies and practices of apartheid segregation have been reactivated with the construction of the Apartheid Separation Wall and the recent changes in Israel’s Basic Laws regarding the rights of the state’s non-Jewish population.

Palestinian historian Elias Sanbar has argued brilliantly that the disappearance of Palestine precedes the emergence of the Zionist movement and the plan to settle European Jewish communities in Palestine. He looked at thousands of postcards produced by European photographers that circulated widely in Europe in the nineteenth century, depicting the so-called Holy Land. The colonial imaginary of Europe, particularly England and France, represented Palestine—specifically, Christian holy landmarks in Jerusalem and Bethlehem—as an abandoned biblical landscape, barely populated, left to disrepair and decay. The Holy Land postcard production is concomitant with the campaigns encouraging French families to settle in Algeria. The challenge of the generation of sons who had risen in revolution from the cold, crammed, and injurious quotidian of refugee camps was also to reverse the legacy of that colonial representation of Palestine.

KE

What media were most important in promoting the Palestinian struggle during the 1960s and 1970s? How has the arrival of new media technologies, from lighter cameras to digital photography and video to the internet and social media, changed the primary modes for documenting Palestinian life, for imagining Palestinian dreams and struggles, and for forging transnational connections?

RS

The PLO’s media production evolved organically, in response to the demands of militants, together with other elements of the organization. The PLO had several departments dedicated to foreign relations, combat operations and phalanxes, information and communication, and national heritage and culture. The Department of Unified Information, as it was known, established the Plastic Arts Section and the Palestine Film Unit (PFU). Chief among this department’s objectives was the aim to disseminate representations of Palestinians on their own terms, or, in other words, to reverse the impact of disappearance and to counter the impact of dispersal by emboldening the sense of peoplehood among Palestinian refugees, Palestinians in the diaspora, and Palestinians in the Occupied Territories. Both the Plastic Arts Section and the PFU mobilized artists, filmmakers, and intellectuals to produce work in solidarity with the cause and to win the hearts and minds of international publics.

Posters were particularly effective as a means of communication; they were lightweight, easy to reproduce in large quantities, and convenient to circulate. They mediated an iconographic imaginary, popularized slogans, and disseminated national symbols. It is mostly through posters that the Palestinian freedom fighter, or fida’i, became iconic, and the same can be said of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the oranges of Jaffa. The prompts for their production were diverse—for example, posters were made to honor the memory of martyrs, rally masses for a march or event, and commemorate massacres and mark patriotic celebrations, thereby creating a national calendar. In addition to Nakba Day on May 15, there was Land Day on March 30, the Day of the Palestinian Child, Palestinian Women’s Day, Palestinian Martyrs’ Day, and so on. Given the wide roster of artists producing these posters, the graphic languages are accordingly very diverse and offer myriad imaginings and visual associations with Palestine.

A similar phenomenon happened with film, with the difference that non-Arab filmmakers were able to travel to Palestine and capture footage. Although film production was an expensive venture, the PLO—and within it, the PFU, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), and the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP)—sponsored films. However, the PLO was not the only commissioning or enabling entity. Small organizations, like the Fifth of June Society, were also funding the production of films. Rosemary Sayigh, a member of the group, remembers that the Fifth of June Society was formed by “a group of nationalist Palestinians—people like Fuad Itayem, Antoine Zahlan, Shafiq Kombarji, and others—soon after 1967, with the goal of changing the West’s misperceptions.”{1} Everyone understood the importance of the medium in this era of cinéma vérité and direct cinema. Nothing could rival the power of exhibiting the reality of Palestine and Palestinians worldwide through the moving image. Furthermore, the 1960s and 1970s were the age of television, access to which the PLO did not have; the production of films was the equivalent of an alternative screen, the revolutionary newsreel.

The advent of lightweight and affordable digital camera technology at the turn of this century marked a milestone worldwide, beginning with democratizing access to the production of moving images, personal and subjective narratives, and representations. Making films was no longer as costly an undertaking, nor was it conditioned on the commitment of a whole slew of people. These technologies widened the range of Palestinian voices surging into the cultural scene, locally and internationally. However, by the 2000s, the imperatives driving artistic expression and the political context had also changed drastically. Palestinian cinema has become impressively plural and polyphonous as it frays the illustrious circuits of international film festivals, large and small. Meanwhile, internecine power struggles have crippled the political establishment’s ability to secure the well-being of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. The political class seems entirely bankrupt of ideas and principles, while artists, filmmakers, writers, and academics have become the most potent advocates of Palestinians’ right to self-determination and a life of dignity.

KK

Screening Palestinian films of the 1960s and 1970s in public spaces was a way not only to show moving images of the lived experiences of displacement and dispossession, but also to gather people to talk about these realities. Rasha and I heard stories about touring screenings in Japan of films about the struggle and the war in Lebanon, which had been brought back by Japanese individuals from trips to Lebanon in the 1970s. In Italy, there were itinerant exhibitions that included events or happenings in town squares; the art collective L’Arcicoda, for example, organized events that combined artworks with informational posters explaining what was happening in Palestine and to Palestinians, as well as large banners and, maybe most importantly, music around which people gathered. To bring awareness to the massacre at Tell al-Zaatar, the group mounted a series of these itinerant events/exhibitions all over Tuscany and also in Mestre as part of the Venice Biennale in 1976. This collective not only was concerned with the Palestinian cause but also organized similar events in response to the coup in Chile and the war in Vietnam, for example.

Today, of course, with social media and live streaming, in theory it’s even easier to see what is happening across the world, but in terms of people finding it, the fight is with the social media companies’ policies and censorship, as well as algorithmic bias. If citizen-journalists can use TikTok, Instagram, or Facebook to live stream events like attacks on Palestinians in Sheikh Jarrah, the issue is not only if and how users will come across these videos, but also how news organizations and journalists amplify or silence those voices through their own channels. There have been countless reports of systematic digital repression and censorship on platforms like Facebook and Instagram, especially in the last few years. In addition, new laws banning support for or even discussion of BDS in countries including the US, the UK, France, and Germany have criminalized people for allegedly anti-Semitic sentiment, leading to many unjust defamations and arrests, and in some cases to violence, as during documenta in 2022.

KE

Can you reflect on your curatorial work—primarily with Past Disquiet, but potentially widening outward to other projects of yours—as an act of retrieval, commemoration, reconstruction, or intervention across a generational gap? In cocurating Past Disquiet, did a generational difference manifest in terms of your relationships to the histories you researched together? How did the language used by Palestinian artists and intellectuals change after the period covered in Past Disquiet?

RS

I have been extremely privileged to find institutions (and funding bodies) interested in engaging, supporting, and hosting the eccentric projects that have intrigued me. I generally find curatorial practice to be far more enriching and meaningful when it is dialogical; I am never interested in listening to my own thoughts but in sharing, discussing, bouncing ideas back and forth. Therefore I have done my best to avoid venturing alone, and I have been very privileged to find extraordinary accomplices, such as the late Jytte Jensen, curator of film at MoMA, with whom I concocted Mapping Subjectivity: Experimentation in Arab Cinema from the 1960s to Now (2010–12); Koyo Kouoh, the curator of art with whom I concocted Saving Bruce Lee: African and Arab Cinema in the Era of Soviet Cultural Diplomacy (2018); and Kristine Khouri, my priceless accomplice and friend in the Past Disquiet adventure for almost ten years. Otherwise, I would not know how to describe or analyze my curatorial practice, but the production of knowledge, poetics, and affect that it produces fascinates me and might arguably be a central leitmotif. Kristine is an extremely thorough and conscientious researcher. She was born and raised in the US, to Lebanese parents, while I grew up in Beirut, with a Palestinian father and a mother who is part Syrian and part Lebanese. I think I am more than ten years her senior. Respectively, our personal lived experiences are starkly different, but they became our strengths and enabled us to sort out tasks.

One of the challenges of Past Disquiet was to think historically, which may sound odd given that the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s are not such a long time ago. The documents, photographs, pamphlets, and catalogs we were studying, however, had all outlived the political and cultural realities to which they were indexed. Thinking historically implied the translation of political, cultural, and art-historical terms that had become obsolete or fallen into disuse. For instance, cadres of the PLO, as well as artists closely associated with political struggles, described themselves as militants, not activists. The plastic arts were salient; there were no references to the visual arts. And in the time span that the project covered, from the 1960s to the 1980s, the Palestinian revolution became the Palestinian cause.

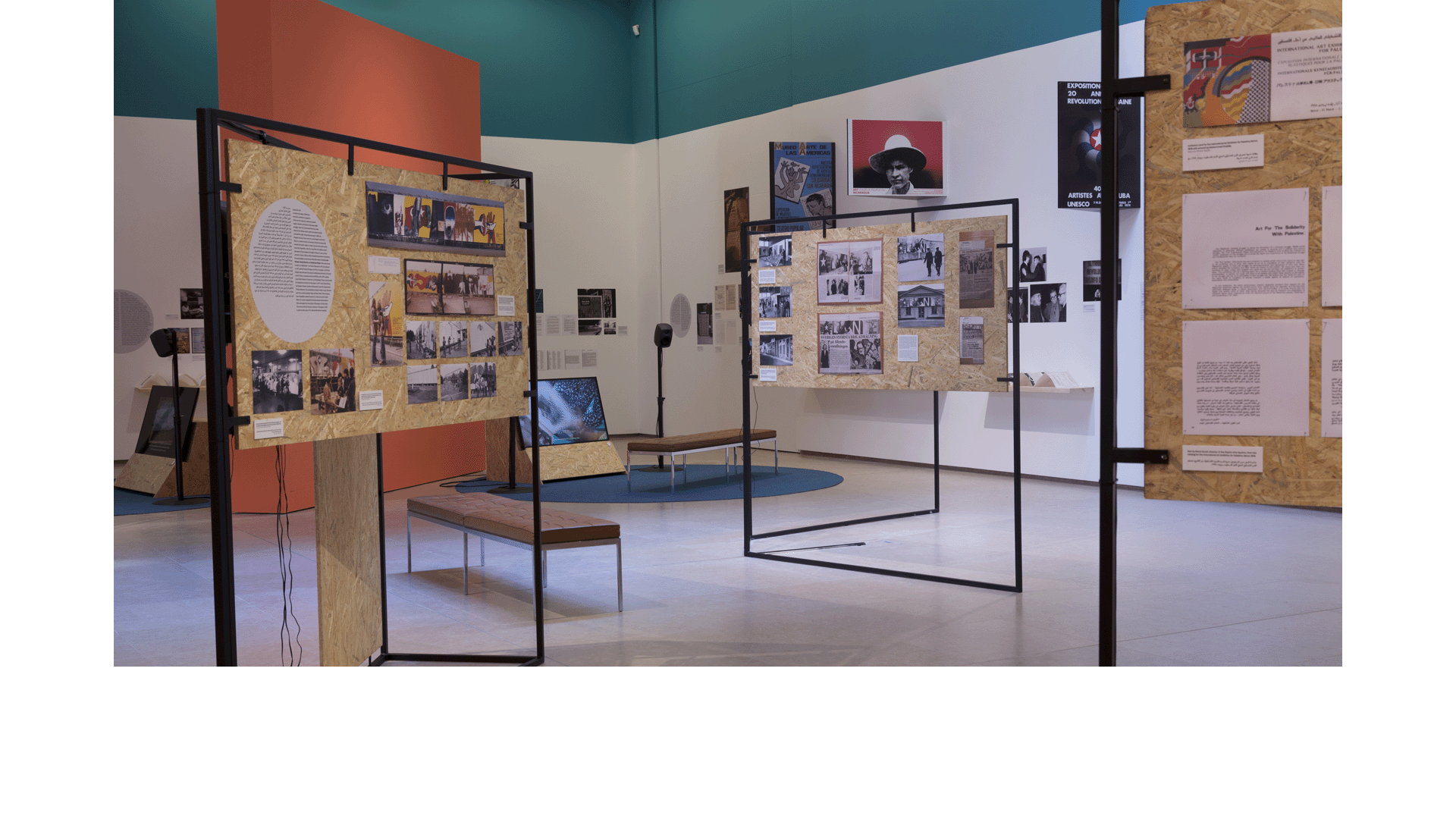

PAST DISQUIET: NARRATIVES AND GHOSTS from the INTERNATIONAL ART EXHIBITION FOR PALESTINE, 1978, installation view, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 2016. Image courtesy of Laura Fiorio/Haus der Kulturen Der Welt.

PAST DISQUIET: NARRATIVES AND GHOSTS from the INTERNATIONAL ART EXHIBITION FOR PALESTINE, 1978, installation view, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 2016. Image courtesy of Laura Fiorio/Haus der Kulturen Der Welt.

KK

To add to that, I think collaborations allow for different perspectives to live simultaneously next to each other. Neither Rasha nor I experienced the events of the 1970s as adults (I wasn’t even born). For Past Disquiet, telling stories as members of generations that didn’t live the events themselves certainly gave us a distinct perspective: we weren’t writing ourselves into that history in a particular way, but rather acknowledging our responsibility in presenting different memories and experiences, and owning our own voices in sharing these stories and our interpretations of the archives we found. Having been born and raised in the US, but with parents from Lebanon who immigrated during the war with two other daughters, in much of my work (and personal experience in Lebanon) I have tried to unearth sometimes intentionally hidden stories—replete with surprises and dead ends. My own interest in cultural and art histories has expanded to places I have no relationship to; within this project alone, Palestine becomes an entry point to look at artistic practices and solidarity in Japan, Nicaragua, Chile, and South Africa. Collaborating for over a decade with Rasha on this project, new directions and deeper research opportunities have come up, even recently, and we try to find ways to pursue them to continue to flesh out new stories.

Title video: Exhibition views, Past Disquiet, Sursock Museum, Beirut, 2018. Courtesy of Christopher Baaklini/Sursock Museum.

{1} Mayssun Soukarieh, “Speaking Palestinian: An Interview with Rosemary Sayigh,” Journal of Palestine Studies 38, no. 4 (July 2009): 13.