Visible Records of a Definite Problem

Stefan Tarnowski

I learned to think of a picture not as a finished product exposed for the admiration of virtuosi, but as the visible record . . . of an attempt to solve a definite problem.

—R. G. Collingwood{1}

****

In November 2010, Omar Amiralay, the great pioneer of documentary cinema in the Arab world, gave a final interview before his sudden death, which would come just a month prior to the start of the Syrian revolution. The interviewer, Sandra Iché, proposed a thought experiment: Suppose the year is 2030, and you’re remembering the present.

Excerpt from “Ellipses, a Conversation with Omar Amiralay,” interview by Sandra Iché, November 2010.{2}

The interview is a strange document. As Amiralay plunges deeper into dystopian reverie, the future recedes into the present. It becomes harder and harder to make out whether Amiralay is being deadly serious or playfully flippant.

For a few years, writers and documentary filmmakers who knew Amiralay would sometimes mention this interview, saying how sad it was that he died before witnessing the inspiring events of the Syrian revolution, that he had died in a state of pessimism, only able to imagine a future where Syria is ruled by “Hafez Bashar al-Assad,” a name that evokes the inheritance of power in Syria by Bashar’s son and Hafez’s grandson. In November 2010, the future looked like more of the past, a grotesque accumulation of Assads in Syria and capital in Lebanon. It was tragic, his friends and colleagues would say just a few months later, that this principled, dissident intellectual never experienced the paradigm shifts of 2011.{3} By 2022 the wheel seems to have come full circle. Amiralay’s dystopian musings sound prescient.

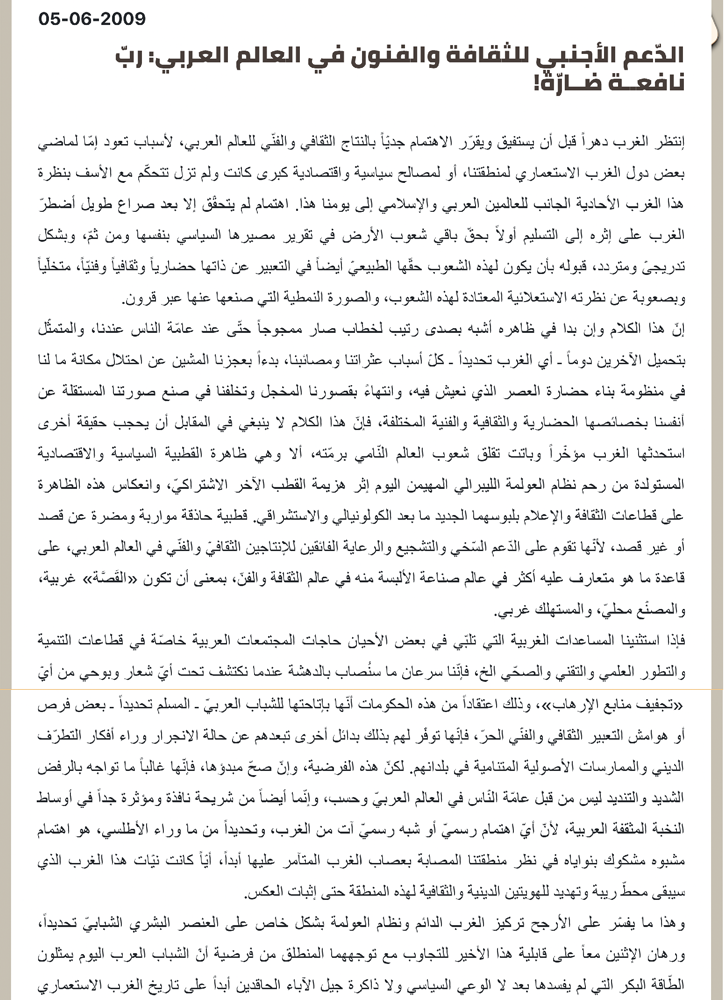

An article by Amiralay from 2009 gives a snapshot of the political and intellectual questions he was asking at the time. Published in al-Safīr—a Beirut-based newspaper that Amiralay would surely have avoided post-2011 for its political stance against the revolution—the article focuses on the War on Terror and the question of al-tamwīl al-ajnabī (foreign or Western funding) for Arab culture, media, and the arts. Amiralay asks why the West had suddenly started funding Arab cultural production so generously. He questions the impact of foreign funding on everything from corrupt local partners to disengaged local audiences:

Omar Amiralay, “الدّعم الأجنبي للثقافة والفنون في العالم العربي: ربّ نافعــة ضــارّة! [Foreign Funding for Art and Culture in the Arab World: A Useful Harmful Master!],” AL-SAFĪR, June 5, 2009.

Omar Amiralay, “الدّعم الأجنبي للثقافة والفنون في العالم العربي: ربّ نافعــة ضــارّة! [Foreign Funding for Art and Culture in the Arab World: A Useful Harmful Master!],” AL-SAFĪR, June 5, 2009.

On the surface, [this discourse on Western funding] sounds like an echo of the tendency we have to perpetually blame the other—and the West in particular—as cause of all our problems, beginning with our shameful inability to occupy a place for ourselves within the system by constructing a civilization fit for the age in which we live, and ending with our embarrassing shortcomings and backwardness in producing an independent image of ourselves in our own civilizational, cultural, and artistic specificity and difference. But this discourse need not obscure another fact recently brought about by the West, a source of anxiety for all the peoples of the developing world, namely a kind of political and economic polarization born from the womb of the liberalism and globalization hegemonic today after the defeat of the other, socialist pole. This phenomenon is reflected in the spheres of culture and media, dressed up in their new postcolonial and post-Orientalist garb. This polarization is skillful, evasive, and harmful (whether intentionally or not), because it’s based on the generous funding, encouragement, and unrivaled care for cultural and artistic production in the Arab world. It adopts methods more common in the fashion industry than in the arts: the “story” is Western, the production is local, but the consumer is Western.{4}

As with many of the modernist intellectuals of his generation, Amiralay is self-critical, bemoaning the state of the arts in the Arab and Muslim world, and at the same time suspicious of the West, questioning the motives behind its “generous” funding, which he reads through a history of Western imperialism, the demise of a bipolar political world, and the rise of a counter-terror and security discourse.

For what was in retrospect a brief period after 2011, it was easy to shake one’s head sympathetically but knowingly at Amiralay, who died before experiencing the paradigm shift of the Arab Spring. For a moment, the Arab revolutions meant that the urgent questions weren’t formulated on the basis of relations to the West, on the problem of Western representations, Western funding, or Western audiences. This was the feeling felt in particular by a younger generation for a good part of the last decade; a feeling I certainly shared. It was captured, for example, by Nasser Abourahme’s enthusiastic hope that the postcolonial era might be over, that it might finally be possible to think “outside the shadow of the figure of the West,” that “there is, now more than ever, a need, an urgent need, to forget the West. Not just to provincialize it, but to really forget it.”{5}

By late 2019 and early 2020 in Beirut, when Lebanon belatedly attempted its own revolution, the notion of foreign funding had once again become an accusation. Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah, who had intervened in Syria on the side of Assad to help defeat the popular revolution, and who opposed the popular uprising in Lebanon, would invoke the specter of foreign funding, index finger raised, to berate the Lebanese during his televised speeches. There was no revolution, just a movement (hirāk) funded by foreign embassies (safarāt) luring protestors into the streets with free foreign food. Many of us laughed: the leader of a militia funded by Iran raising suspicions about foreign funding couldn’t be more hypocritical. But the best response came from a chant composed by Nasawiya, a group of Lebanese feminist activists: “Our revolution’s not just a movement! / We’re eating manoushe / we’re not eating sushi / so why do they keep talking about embassy funding?”

Protestors in Beirut chant: “Thaw thaw thawra! / Our revolution’s not just a movement! / We’re eating manoushe / we’re not eating sushi / so why do they keep talking about embassy funding?” in November 2019. Video recorded by and courtesy of the author.

In 2021 the question qua accusation was repeated, albeit in a very different guise and with very different intentions, by the art historian Hanan Toukan in her book The Politics of Art, which investigates Western funding for art and culture in Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan, three places largely peripheral to the Arab revolutions. For Toukan, the controversy over al-tamwīl al-ajnabī isn’t something that comes in and out of view under changing historical circumstances; rather, Toukan argues, it is the fixed “byproduct of 200 years of colonial encounters between the Arab world and the West.” According to the historian, the controversy “is not an empirical one based on objective facts about the impact of international funding on local NGOs. Instead it reflects the historical relationship between the Arab world and the West.”

In the field of the arts, how this unequal relationship of power between funder and recipient materializes is hotly contested. What I mean is how recipients of funds, whether artists or local arts-supporting initiatives acting as “middlemen” with politically vested interests in the region, play a role in shaping the aesthetical and formal practices of cultural production. By extension, how do such initiatives end up influencing the way we understand the role of the artist as a critical voice for change in society?{6}

For a few brief years, the urgent questions in the Arab world weren’t about the West and its funding, and the questioners were younger and more anonymous.{7} Along with despair for the future, many of the questions from the past have returned.

****

As part of a forthcoming special issue of World Records, I will be putting together a dossier on Bidayyat, a Syrian organization that was set up in response to the Syrian revolution to support a younger generation of Syrians, Palestinians, and Lebanese in experimental documentary.{8} Bidayyat was founded in 2013 in Beirut and recently had to close its offices in the city, amid the violence of two defeated uprisings and an economic collapse. Through a structure of mentorship, Bidayyat trained over a hundred young people in documentary cinema, producing eight feature films and over fifty shorts during a roughly ten-year period.

Bidayyat offers a glimpse of intergenerational exchange—at times collaborative, at others antagonistic—among activists and filmmakers at a particular historical conjuncture. It also offers a view onto the controversy of Western influence. The organization received foreign funding from Germany’s Heinrich Böll Foundation, and many of the films it produced circulated in Western film festivals, thus fitting the model Amiralay was suspicious of—“the ‘story’ is Western, the production is local, but the consumer is Western.” Recently, Bidayyat and the films it produced have been criticized along these lines.{9}

David Scott has described a paradoxical aspect of temporality within intergenerational dialogue. Generations can at once be co-temporary, in the sense of being present at the same time, but not contemporary, not motivated by the same pasts, “nor . . . haunted by the same displacements of futures past.”{10} In his work on intergenerational dialogue, Scott draws on R. G. Collingwood’s theory of the “logic of question and answer,” which entails a shift of focus in the writing of intellectual histories.{11} When encountering propositions or arguments, such as those concerning foreign funding and audience, one should consider the often tacit questions that a generation of thinkers might be trying to answer, questions that might need to be carefully reconstructed for these thinkers’ arguments to make sense. This in turn makes possible a kind of critical generosity: instead of seeing an argument as wrong, misguided, or ill-judged according to some external measure, the focus shifts to evaluating it on the basis of the historical questions that have been excavated and reconstructed. Scott calls this contextual and reconstructive work that restores a question to its answer a “problem-space.”{12} In reconstructing a problem-space, it becomes apparent that a question from the past can fade out of view as well as reappear. A generation might think that it has solved a question, or that this question is no longer pressing, but the question can also become urgent once again for a variety of historical, political, and technological reasons. That’s certainly the case with two issues related to the history of Arab cinema: foreign funding and Western audiences.

In a recent article comparing Syrian documentary cinema of the last decade with Lebanese documentaries from the 1970s, the French film scholar Mathilde Rouxel also adopts an intergenerational framework, arguing that there is a “generational gap” between the work produced by Bidayyat and films made in the past. Both kinds of political cinema—Syria in the 2010s, Lebanon in the 1970s—“stand against war, repression and intimidation,” but that’s where the similarities end. Films from the struggle in Lebanon are acts of collective solidarity, “giving voice to those whose existence is denied,” and emerging from the bosom of revolutionary organizations. By contrast, films from the present struggle in Syria produced by the likes of Bidayyat, she argues, are funded by NGOs, privilege individual narratives and storytelling, and are probably not made for a popular Syrian audience.

Today, the purpose behind films shot in the war seems to have changed. From an intolerable need to inform, the film has become the aesthetic construction of an individuality in resistance, legitimized by the presence of the director and/or their friends and relatives on the ground. Today, the primary necessity is no longer to document the invisible, but rather to expose a personal perception of an over-mediated conflict. Instead of mobilizing to defend a cause or to denounce the injustice of a situation lived by a people or a group of people, these films tend to stage individual histories in a setting of war, at the expense of a factual documentation of the wider history.{13}

The present, in Rouxel’s comparison, doesn’t measure up to the past.

But what is the right measure of the present and its practices? Is it to be found in an older generation characterized by some quality—for example, “filmmakers [who] spoke from their homeland, for their people”?{14} Are today’s filmmakers—funded by foreigners and premiering their documentaries in Europe—perhaps like today’s militants, hopelessly co-opted by neoliberal logics, and simply lacking the capacious visions of emancipation that animated the past?{15}

One should consider the often tacit questions that a generation of thinkers might be trying to answer, questions that might need to be carefully reconstructed for these thinkers’ arguments to make sense.

Fadi Bardawil has memorably called the use of ideal categories to govern comparisons between liberation struggles past and present, here and elsewhere, “anti-imperialist transcendentalism.”{16} There is no ideal category of militancy, he argues, whether in intellectual production or revolutionary struggle. The point of generations as an analytic is precisely to show how the filmmakers and intellectuals of the past were animated by theoretical, political, and even aesthetic questions that might not be urgent, relevant, or practical for a younger generation, which has to respond to a different set of theoretical questions, historical conditions, aesthetic regimes, and political dilemmas.

Two moments from the history of Syrian cinema can help illustrate the limitations of generational comparison according to some fixed measure, such as foreign funding or local audience. For over forty years, and especially after Hafez al-Assad’s 1970 Corrective Revolution, Syrian cinema was under the centralized control of the state through the National Film Organization (NFO), a branch of the Ministry of Culture. The NFO produced one film a year, sometimes a film every two years. Filmmakers were forced to navigate many hurdles, including bureaucratic processes, the cliques and sycophants holding sway at any given time in the NFO, perhaps even the whims of a minister’s patronage—then, finally, their films might get funded. But while funding from the NFO might guarantee production, it didn’t guarantee a local audience. Once produced, a film still had to pass through the censor’s office.

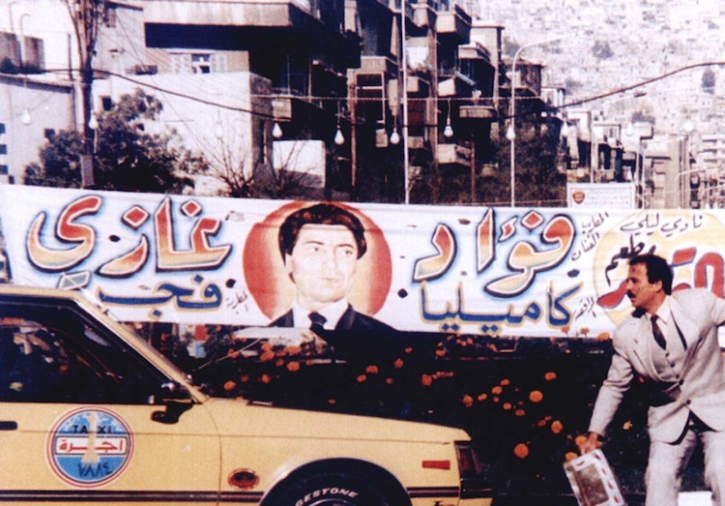

Despite having to negotiate this bureaucracy, films from the period were anything but propaganda. Trained in Soviet and Eastern Bloc film schools, this generation of filmmakers developed a rich allegorical language with which to address, and critique, life under the first Assad regime.{17} And yet, even with state funding in hand, and having passed their scripts and treatments through the censor’s office, these filmmakers couldn’t always reach a Syrian audience. A film as canonical as Ossama Mohammed’s Nujūm al-Nahār (Stars in Broad Daylight, 1988) managed to win funding from the NFO, was then screened at Cannes and Rotterdam, even representing Syria there, only to be banned from screening in Syrian cinemas.{18} One of Omar Amiralay’s best-known documentaries suffered a similar fate. Everyday Life in a Syrian Village (1974) received funding from the NFO, but was then banned by the censor. It premiered in West Germany in 1976, where it won a prize at the Berlin International Film Festival.

STARS IN BROAD DAYLIGHT (Ossama Mohammed), a fictional depiction the disintegration of a family during wedding preparations, premiered at the 1988 Cannes Festival.

STARS IN BROAD DAYLIGHT (Ossama Mohammed), a fictional depiction the disintegration of a family during wedding preparations, premiered at the 1988 Cannes Festival.

Unsurprisingly, Western theorists haven’t been able to agree on what to make of this absurdity, where a film could be both funded and censored by the same ministry, both represent a country abroad and have no audience at home. For some theorists, these films were signs of resistance, the persistence of politics—embodied in the person of dissident directors—despite the Assad regime’s attempt to kill it.{19} For others, the authorities were allowing criticism to take place so long as they could manage its intensity by controlling its circulation.{20} For others still, the notion that this was about tanfīs—controlled criticism that amounted to venting or letting off steam—misunderstood power’s fundamental “ambiguity,” even as it operates in an authoritarian regime.{21} What matters for this essay is that the questions of funding and audience have never been straightforward, not even when films are subject to the centralized control of state production ostensibly for a national audience.

If allegorical fiction was the hallmark of the NFO generation, just as popular satellite TV series were characteristic of the following generation, then the central mode for filmmaking in the period since the 2011 Syrian revolution has been documentary. In the span of a decade, Syria has gone from a country that produced one film a year, sometimes one film every two years, to “one of the most important countries in the world for the documentary film industry.”{22} Documentaries by Syrian filmmakers have won prizes and nominations just about every place, across the whole spectrum from mainstream to experimental to fringe, including at Sundance, the Oscars, the BAFTAs, Cannes, Toronto, FIDMarseille, Locarno, Venice, and the Berlinale. Syrian documentaries have been produced and distributed by everyone from ARTE to Channel 4 to Amazon, as well as simply uploaded to Vimeo for free on a weekly basis by the anonymous collective Abounaddara to bypass traditional distribution methods.{23} In fact, images are one of Syria’s greatest exports, at least in quantity, only recently overtaken by Captagon.{24} There have been more hours of footage from Syria uploaded on YouTube than there have been hours of real time since 2011, and Syrian documentary is a small province of that vast territory of images.{25} Even within the limited scope of documentary cinema, Syrian images have attracted big audiences and even bigger budgets. Feras Fayyad’s The Cave (2019), for example, cost over a million dollars.{26}

By comparison to those big-budget productions, Bidayyat films are small fry. Bidayyat was a nonprofit that engaged in lengthy periods of mentorship to train young media activists in the techniques of documentary filmmaking. Often activists would arrive from long years of siege, crossing the border to Lebanon or Turkey with hard drives full of footage. Sometimes the films made at Bidayyat bore a journalistic or humanitarian imprint, with activists narrating their footage using the langue de bois of war reporting or humanitarianism. But they could also be much more militant than that, with activists filming alongside fighters as they attempted to wrest towns and cities from Assad control. The work of turning this footage into experimental documentary was painstaking, with no guarantees of success.

In Still Recording (2018), for example, shot over the course of four years by a group of friends living in Douma under siege, the directors barely had any formal training in filmmaking. When Saeed al-Batal and Ghiath Ayoub arrived in Beirut after years of revolution and siege, Bidayyat provided them with equipment and a stipend to embark on the lengthy process of turning their footage into a film. They had over five hundred hours of raw footage, and the editing process was fraught and frequently misfired. They burned their way through an artistic director and an editor, Rania Stephan and Raya Yamisha, before managing to finish their film with Qutaiba Barhamji.{27} After the Venice Film Festival, where Still Recording won multiple prizes, al-Batal had hoped to be able to return to Beirut, but the Lebanese authorities revoked his visa and he was suddenly exiled for a second time. He eventually made his way from Italy to Germany, where he still lives in exile. After the festival circuit, Still Recording went into general release in French cinemas, and then streamed on various platforms in subsequent years.

Excerpt from STILL RECORDING (Saeed al-Batal and Ghiath Ayoub, 2018).

Throughout, al-Batal and Ayoub organized small screenings for Syrian audiences in the diaspora and in parts of the country still outside of regime control. I attended small screenings in Beirut and Istanbul, and others were organized in Damascus Province. It was touching that at one screening in Istanbul, I saw a media activist, Ghaith Beram, living in exile in Istanbul, reunited for the first time in three years with some of his footage that had been cut into the film. Between activists, who often formed local “media offices,” there was frequently a sense of collective ownership over footage. Still Recording cost a fraction of Fayyad’s The Cave; and although screening and winning prizes at Venice was a source of pride for the directors, it would be hugely reductive to claim that it was their or Bidayyat’s purpose for making the film.

Yet, the fact that Bidayyat’s films premiere in European film festivals is what makes the organization controversial to some, while it is the kind of funding the organization receives that has been criticized by others. In Rouxel’s article, the question of audience becomes a sort of accusation:

Who do these films address? The audience of contemporary Syrian filmmakers is not the same as the films distributed in mainstream channels during the 1970s. Even more important, the images are not chosen or mounted for the sake of a unitary political and artistic discourse as they were in the militant films of the Lebanese war. Their places of recognition are the major international film festivals—Cannes, Venice, Berlin, Rotterdam, Locarno—mostly for a European elite sensitized to the issue of documentary creation, and in search of an artistic avant-garde. Common Syrian people are not expected to be seated in front of the cinema screens of Western capitals.{28}

These statements are puzzling. What sort of ideal audience is being imagined here? And where are the “common Syrian people” today? Does Rouxel mean the five million displaced, over one million of whom are now living in Europe, in Western capitals such as Berlin? And what about the argument made by Kay Dickinson that one of the hallmarks of the region’s cinema has long been that it travels, that it’s hard to fit films squarely into national film industries?{29}

Before it closed its offices in Beirut in 2021, the last feature Bidayyat produced was Abdallah al-Khatib’s Our Little Palestine: Diary of a Siege (2021). The film is nothing if not a story of displacements. Al-Khatib begins by attempting to capture testimonies from the Nakba generation of Palestinians, whose experiences of pre-1948 life in Palestine he fears might be lost to death or forced displacement. But he’s also drawn to the Syrian revolution, and ends up making a film about the starvation siege waged against Yarmouk, the Palestinian camp at the edge of Damascus which was once known as “the capital of the diaspora.”

Excerpt from OUR LITTLE PALESTINE: DIARY OF A SIEGE (Abdallah al-Khatib, 2021).

Abdallah al-Khatib participated in his first Bidayyat workshop online while under siege, and his second following exile from northern Syria to Istanbul, before finishing the majority of the post-production while living in Münster; he now lives in exile in Berlin. He has organized screenings for friends and small cine-clubs in Azaz, and he’s still active with a collective of writers called SARD, who are now exiled everywhere from Paris to Idlib, Azaz to Berlin.{30} The film traveled the festival circuit, winning prizes along the way, and is now in general release in France. Ali Atassi, Bidayyat’s founder, is particularly proud that despite winning funding for the film from the Al Jazeera series Witness, he was able to negotiate for al-Khatib to retain final cut before the film aired on TV. In short, it would be a very strange question indeed to ask al-Khatib whether he intended his film for “common Syrian people,” or to accuse him of privileging an “artistic avant-garde” or “European elite” while making this strange, imperfect, priceless, and vital document of a place that no longer exists.

It would also be strange to turn Our Little Palestine into a story about the Heinrich Böll Foundation funding Bidayyat, or Still Recording into a story about a Syrian film being made for an elite European festival. The questions these films are trying to answer can’t be reduced to Bidayyat’s funding model or to the festival circuit. As an organization Bidayyat was trying to respond to a different series of questions and problems. Some questions had to do with anxieties over posterity: What stories can be told about what happened over the last ten years of revolution and war, hope and defeat, creativity and cruelty? Who will get to tell those stories? Others were economic: Can Bidayyat create structures for young media activists and filmmakers to maintain some control over their own images?

Are those questions less revolutionary than the questions asked by past generations, or by people elsewhere? I’ll leave that for others to judge. These are Bidayyat’s questions, and we should at least judge their answers on the basis of those questions, their historical conditions, and their political dilemmas. Bidayyat provided clear answers to those questions: It wanted young people, trained in a tradition of Syrian and regional experimental documentary, using footage they shot, which they still owned, and authored under their own names, to tell the story of the Syrian revolution, whether in liberated Douma, besieged Yarmouk, or regime-controlled Damascus, even if those stories end in defeat and despair.

The films often do end in defeat and tragedy, much as the Syrian revolution itself did. But then, as Hannah Arendt has argued, this might also be the essence of political action—that it’s contingent, that one embarks on it without guarantees, that it might end in suffering, and that history is not something made but an accumulation of doings, of acts.{31} By the same token, these films by Bidayyat are nothing if not political acts. They emerge from a generational milieu with a set of problems that urgently had to be addressed. Each film is the visible record of an attempt to solve a definite problem.

Title Video: EVERYDAY LIFE IN A SYRIAN VILLAGE (Omar Amiralay, 1974) \ A LETTER FROM BEIRUT (Jocelyne Saab, 1978) \ STARS IN BROAD DAYLIGHT (Ossama Mohammed, 1988) \ OUR TERRIBLE COUNTRY (Mohammad Ali Atassi and Ziad Homsi, 2014) \ STILL RECORDING (Saeed Al Batal and Ghiath Ayoub, 2018) \ OUR LITTLE PALESTINE: DIARY OF A SIEGE (Abdallah al-Khatib, 2021).

{1} R. G. Collingwood, An Autobiography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939), 2.

{2} “Ellipses, a Conversation with Omar Amiralay – English Subtitles,” interview by Sandra Iché, translation by Ziad Nawfal, August 10, 2016. See also Sandra Iché and Nisreen Khodr’s installation video “Archives du futur – Beyrouth, novembre 2030” as part of the Wagons Libres project.

{3} Hala Abdallah’s recent film Omar Amiralay: Sorrow, Time, Silence (2021)—a beautiful meditation on the loss of Amiralay before the Syrian revolution, and on the loss of the Syrian revolution in the absence of Amiralay—briefly discusses this point.

{4} Omar Amiralay, “الدّعم الأجنبي للثقافة والفنون في العالم العربي: ربّ نافعــة ضــارّة! [Foreign Funding for Art and Culture in the Arab World: A Useful Harmful Master!],” al-Safīr, June 5, 2009. All translations, unless otherwise stated, are by the author.

{5} Nasser Abourahme, “Past the End, Not Yet at the Beginning: On the revolutionary disjuncture in Egypt,” City 17, no. 4 (August 2013): 431. See also Hamid Dabashi, The Arab Spring: The End of Postcolonialism (London: Zed Books, 2012).

{6} Hanan Toukan, The Politics of Art: Dissent and Cultural Diplomacy in Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2021), 38.

{7} See, for example, Zeina G. Halabi, The Unmaking of the Arab Intellectual: Prophecy, Exile and the Nation (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017).

{8} The politics of generations is the central theme of this special issue of World Records, which I’ll be co-editing with Kareem Estefan.

{9} Mathilde Rouxel, “Mutations of Arab political filmmaking,” Syria Untold, December 11, 2019.

{10} David Scott, “The Temporality of Generations: Dialogue, Tradition, Criticism,” New Literary History 45, no. 2 (Spring 2014): 160.

{11} David Scott, Refashioning Futures: Criticism after Postcoloniality (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 5. See also Quentin Skinner, Visions of Politics, Volume 1: Regarding Method (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 103–27.

{12} Scott, Refashioning Futures, 8.

{13} Rouxel, “Mutations.”

{14} Ibid.

{15} For an argument that questions the politics of the Arab Spring along similar lines to Rouxel, see Asef Bayat, Revolution without Revolutionaries: Making Sense of the Arab Spring (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2017).

{16} Fadi A. Bardawil, “Critical Theory in a Minor Key to Take Stock of the Syrian Revolution,” in A Time for Critique, ed. Didier Fassin and Bernard E. Harcourt (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 176.

{17} For more on NFO-period cinema, see Lisa Wedeen, Ambiguities of Domination: Politics, Rhetoric, and Symbols in Contemporary Syria (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999); Rasha Salti, ed., Insights into Syrian Cinema: Essays and Conversations with Contemporary Filmmakers (Brooklyn, NY: ArteEast, 2006); Cécile Boëx, Cinéma et politique en Syrie : Écritures cinématographiques de la contestation en régime autoritaire (1970-2010) (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2014).

{18} For the fullest account of films produced by the NFO, films that “did and did not travel,” see Kay Dickinson, Arab Cinema Travels: Transnational Syria, Palestine, Dubai and Beyond (London: Palgrave on behalf of the British Film Institute, 2016), 39–80. See also Aman Bezreh, “The Syrian public and its cinema: A tale of estrangement – Part I,” Syria Untold, November 28, 2019.

{19} See, for example, Boëx, Cinéma et politique; Josepha Ivanka Wessels, Documenting Syria: Film-Making, Video Activism and Revolution (London: I.B. Tauris, 2019). The notion of the Assad regime “killing politics” comes from Wedeen, Ambiguities of Domination, 32–65.

{20} miriam cooke, Dissident Syria: Making Oppositional Arts Official (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007).

{21} Wedeen, Ambiguities of Domination.

{22} Jacket copy from Wessels, Documenting Syria.

{23} See abou naddara.

{24} Ben Hubbard and Hwaida Saad, “On Syria’s Ruins, a Drug Empire Flourishes,” New York Times, December 5, 2021.

{25} See Jeff Deutch, “Challenges in Codifying Events Within Large and Diverse Data Sets of Human Rights Documentation: Memory, Intent, and Bias,” International Journal of Communication 14 (2020): 5055–71.

{26} Stefan Tarnowski, “Filming Syria: the politics of access,” openDemocracy, February 25, 2020.

{27} All of these editors are contributing to the World Records special issue in various ways.

{28} Rouxel, “Mutations.”

{29} Dickinson, Arab Cinema Travels.

{30} A selection of creative nonfiction written by SARD, with an introduction by Abdallah al-Khatib, will be published as part of the World Records special issue.

{31} See Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).