To Have Many Returns: Loss in the Presence of Others

Rayya El Zein

Entry

Often, it was not the apparently striking or salient element of the dream that was the effective one.

Ursula Le Guin{1}

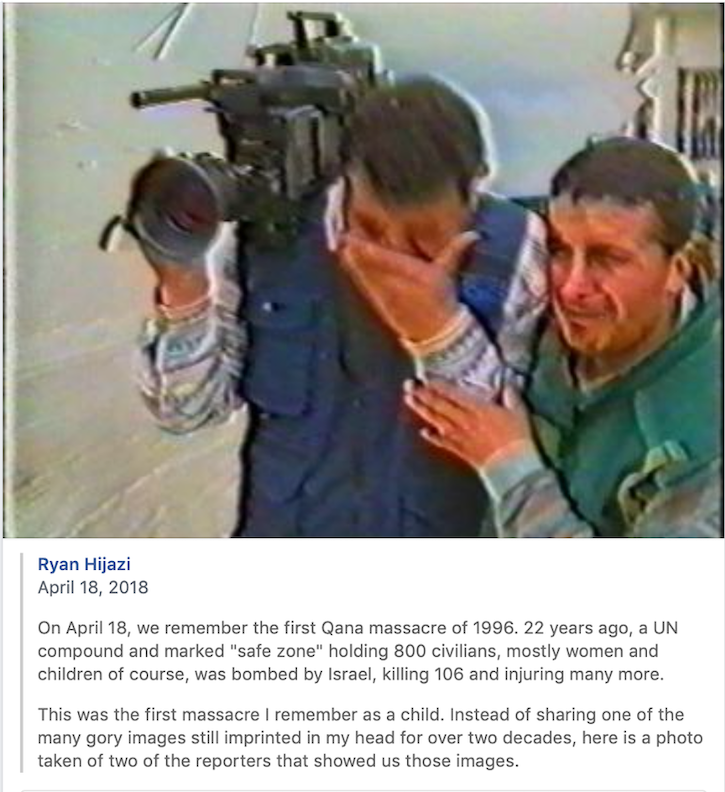

Of all the painful anniversaries now marked on social media, the massacre in the southern Lebanese village of Qana by Israeli forces in 1996 is one of those estranged from me.{2} I think it is because I should remember it, but I don’t. Or, more accurately: I could remember it, but there is nothing there. My memories are blank. In my generation it is one of a dozen turning points, wake-up calls thick with black flags, media-heady days of red and bloodied arms, ashen faces. Friends and colleagues in Lebanon recall it as the first massacre they remember. I don’t remember anything.

Every year, I return to this emptiness. The layers of emptiness. The numbering of it. The April details of death and destruction; the somehow always gaping incompleteness in these commemorations; the blank page of my own memory. These layers of emptiness, hardly unique, find resonant company in the work of generations of survivors, documentarians, activists, poets, artists, and thinkers who have grappled with the ineffability of loss. Authors writing in the thick and the aftermath of disease, genocide, settler colonial dispossession, slave trade, and apartheid all testify to the magnification of the pain of destruction by the intense difficulty of communicating that loss to others. Across time and space, connecting different contexts and disparate destructions, a common element of surviving lies in the impossibility of bearing witness.

Figure 1: Screenshot of a public Facebook post commemorating the massacre at Qana. Ryan Hijazi (April 18, 2018).

Figure 1: Screenshot of a public Facebook post commemorating the massacre at Qana. Ryan Hijazi (April 18, 2018).

This very impossibility is exacerbated by what the Armenian literature scholar Marc Nichanian calls “the catastrophic dimension”—the human will to destroy—manifest in the demand that the witness perform over and over again. Similiarly, writing in the thick of the AIDS crisis—and the will to ignore the suffering of those infected with HIV evinced by US media, government, and the general public—the late American art critic and scholar Douglas Crimp wrote, “the violence we encounter is relentless, the violence of silence and omission almost as impossible to endure as the violence of unleashed hatred and outright murder.” Crimp, like Nichanian, underscores the imperative that the witness return to the scene of destruction to prove that it did happen.{3} If we read laterally, we find this experience among many aggrieved and grieving populations. After more than 500 years of theft and genocide in the Americas at the hands of European colonialists, Indigenous scholar Audra Simpson writes about border crossings as a serial re-enactment of the dispossession of First Nations. In an ethnographic chapter exploring anger as a productive force (to which I return below), she documents her experiences at the US–Canada border proving blood quantum as a constant requirement to return to the site and occasion of erasure.{4} Her description resonates with Nichanian’s claim: “we relentlessly need to prove our own death.”{5}

Other thinkers, witnesses, and mourners offer crucial recognition of this bind that the witness finds herself in: the impossibility of relating this pain and the mandate to relate it again and again. In the context of the legacies of the Atlantic slave trade in the American South, Saidiya Hartman has cautioned against the unnatural pleasure of documenting accounts of the tortured bodies on the receiving end of dispossession, subjugation, murder, and erasure.{6} Drawing attention to “the ways we are called upon to participate in such scenes,” she refuses to reproduce the screams of lacerated slave bodies. Instead, Hartman proposes to “defamiliarize the familiar” in order to illuminate the horrors of slavery—looking at legacies of destruction not as they are manifest in spectacles of terror, but in everyday slave life. This attention to the everyday life of the enslaved resonates in the practice of making, as Judith Butler puts it, “our loves legitimate and recognizable (and) our losses true losses.”{7} That is, Hartman’s refusal to return to and rehearse, and thus to repeat, the whippings, beatings, and murders in written description testifies in its own way both to the humanity of the enslaved and her grief at the slavers’ attempted usurpation of it.

What can be gleaned from an interdisciplinary investigation into the challenges of bearing witness? It is clearly not that the catastrophic dimension is the same for Crimp, Simpson, Nichanian, Hartman, Butler, or the peoples to whom they refer. The distinctions and material realities that structure each loss can only be collapsed at our peril. Rather, taking Nichanian, Hartman, and others together is to sound strategies of hearing as a particular kind of witnessing and testifying. This polyphonic listening is capable of revealing a political soundscape we otherwise miss.

I am bombarded with grief: the grief that I can remember, in the dozen revolutions painstakingly built and sold off; in the countless bombed, starved, and tortured bodies in Gaza, Iraq, Syria, Yemen for all the years I have been aware enough to recognize an Arab body on TV—and the grief that I cannot, like the massacre at Qana; a litany of unremembered massacres and tucked away destructions. In my classrooms and organizing circles, I cannot find the words to relate this gaping emptiness nor to describe the hollow scream that howls for an Arab, brown, Muslim humanity, decade after decade sacrificed on a perverse alter to human rights. In cynical moments, I find myself asking: what good are our relentless efforts to prove our own deaths? What courage can be found to continue making our losses true losses? For, to be sure, the question is no longer to be answered with encouragement, with promises that the whole world is watching, that now “never again” will make it so. Even before the global, viral pandemic that, as I edit this text, threatens to thunder grief on humanity’s collective door, it was not enough to ask why it is difficult to testify to our destructions (we relentlessly need to prove our own death). We must also inquire why it seems impossible for testimonies of loss to reverberate with and to the multiplicities of mourning that mark contemporary political life.

I am troubled by the weaponization of pain and its ultimate failure to build political alliances.{8} I am troubled by the relentlessness—the loudness—required to make pain heard, and how the metaphoric volume of this testimony shapes not only what is heard but what is offered in response. I am sifting through my failure at both bearing witness and attending to others’ bearing witness, at the same time.

There are different routes to trace. There is the question of the appearance of agency and mourning. Here, alongside the other entries in this special issue, I engage with Hannah Arendt’s notions of political life in the polis. Confined to this clearly demarcated political space, I am concerned with her notion of the second birth of political subjects in speech and action seen and heard by others. In my exploration of the limitations of this sphere of appearance, I am guided by Jacques Rancière’s critique of Arendtian agency and his assertion that politics “is not a sphere but a process.”{9} I draw attention to in between moments, what I consider to be the labor of survival ignored without the banner of resistance. These are alternatives to thinking about agency or passivity. The traveler, the citizen journalist, the aunt, the artist, the poet, the mural, and the poster: bearing witness as neither victims nor agents.

This exploration of witnessing and agency, based as it is in an excavation of the work required to be in the presence of others, is also an examination of the public and private lives of trauma. This is what literature scholar Kevin Quashie, in his work on quiet in US Black culture, theorizes as an intimate, internal sphere of politics, at a remove from the mandate for resistance, but potently political nonetheless.{10} Quashie posits his sphere of quiet at a remove from the public sphere of the liberal political subject. Borrowing from Quashie’s deft case for private vulnerability as the ground for collectivity, and the viability of intimate, inward gestures as potent markers for political life, I argue for the recognition of yearning as a political mode of relation capacious enough for both grief and experimentation, testifying and listening, past and future, self and other.

Both of these frameworks for excavating agency and political life—Arendt’s emphasis on the polis as the space where newly born political subjects are “seen and heard” and Quashie’s assertion that quiet is not reducible to silence—should signal that my proposal about the political potential of polyphonic listening need not be located in what sound studies scholar Johnathan Sterne famously coined the “audiovisual litany.”{11} By this I mean that my argument is not primarily that an analytical focus on hearing or aurality will resolve the empirical blind spots of watching and seeing. Rather, it is a proposal to approach our sensing of each other differently. In attending to the polyphonic in political life, I follow anthropologist Anna Tsing in considering polyphony as a variant to the Deluzian assemblage, one that, drawing from polyphony in music, registers “multiple temporal rhythms and trajectories.”{12} Listening, as I propose it here, is not counterposed to seeing or speaking but as a metaphor of attentive relation.

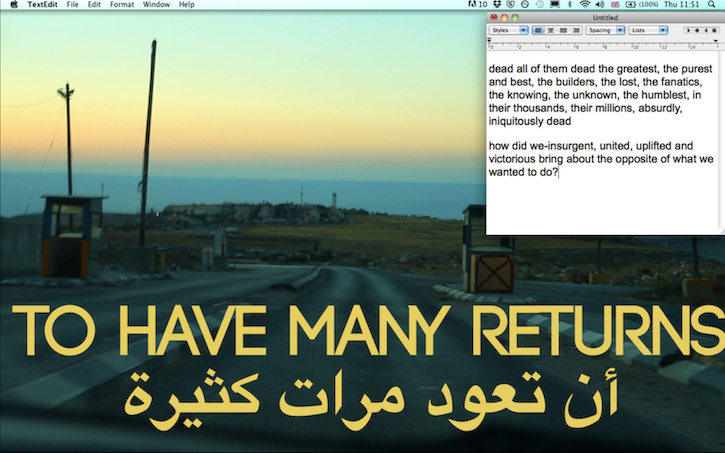

THE PART ABOUT THE BANDITS, PART ONE OF THE INCIDENTAL INSURGENTS, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme (2012-2013).

Drawing from creative archives, another route might be to ask: what is the role of documentary art practice in a cacophonous political soundscape, populated with testimonies to destruction? The Palestinian sound and visual artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme offer one path. Consisting of sound and video installations, collage, original and field recordings, their work courts the boundaries of what one sees and hears, using montage to layer questions and suggestions about the political present. Their collaborative pieces invert the malaise of a generation of Palestinian youth growing up in the shadow of the Oslo Accords to pose a litany of refreshing, halting, and poetic questions that testify to the grief of failure and the loss of grand narratives in the present. Their work disavows dominant representations of the political in the Palestinian context, troubling the temporality of resistance in a post-Oslo landscape and refusing to perform a romantic, idyllic, or otherwise folkloric representation of Palestinian history, politics, and imagination.

Rooted in the sprawling West Bank city of Ramallah, and the failure of the iconic 1991 peace accords that centered that city as de-facto administrative capital of the Palestinian Territories, the duo creatively documents and bears witness to that city’s paradoxes: its growth and emptiness; its prosperity and poverty; its pride and betrayal. Abbas and Abou-Rahme use sound and image, fiction and nonfiction, poetry and documentary, original texts and borrowed prose to construct an urban iconography for Ramallah that stands in affective relief against the romanticized hagiography of the great Palestinian cities of Jerusalem, Haifa, and Jaffa. These layered montages deliberately draw attention to the stalled temporality of Oslo and its failure, in thirty years, to provide the sovereignty it promised Palestinians. In their screenshots, sound and video installations, collage, and other multimedia work, Abbas and Abou-Rahme build on legacies of Palestinian and world literature to offer meditations on and mediations of failure, loss, nostalgia, destruction, and belonging. Their work offers an archive to think with and to borrow from while examining a practice of bearing witness that gropes for new politics.

For example, the duo has a section on their website, their professional portfolio, that hosts what they call samples. These collages stage an artist workstation, juxtaposing color, text, and image. In this one, which is not titled, the predominant image in the screenshot is a photograph of a checkpoint in the occupied West Bank, taken through a car dashboard. Beyond the checkpoint, a blue horizon in green and yellow twilight. Across the bottom third of the image, yellow text is overlaid upon the bottom third of the screen and reads in capital letters in English and Arabic, TO HAVE MANY RETURNS. And in the upper righthand corner is an open text window with prose ending in the question: how did we–insurgent, united, uplifted and victorious– bring about the opposite of what we wanted to do? This question, preceded as it is by a litany of dead—dead all of them dead, the greatest, the purest, the best, the builders, the lost, the fanatics, the knowing, the unknown, the humblest in their thousands, their millions, absurdly, iniquitously dead is another, excellent place to start.

Figure 2: UNTITLED SCREENSHOT, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme (date unknown).

Figure 2: UNTITLED SCREENSHOT, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme (date unknown).

Despite its seeming simplicity, “untitled screenshot” is a loaded volley into political discourse and artistic practice for the Oslo Generation. With it, Abbas and Abou-Rahme pose questions for a new generation of Palestinian audiences by starting from an urgent and unique articulation of failure: both triumphant (insurgent, united, uplifted, and victorious!) and unquestionably defeated. It is also a halting meditation on bearing witness. The montage the duo builds succeeds in refuting and subverting a mainstream pattern of commemoration, articulation of grievance, and remembering.

I’d like to mimic and borrow from Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s creative practice of layering. In layering my own gathered corpus of materials, I attempt my own poesis around our contemporary moment’s deafening demands for solidarity and exasperated struggles over representation. From my own position between Palestine and somewhere else (Lebanon, the US, Europe), compelled to understand my own access to Palestine and listen to the loss and destruction of Indigenous lands in the Americas, as well as the terror of state violence in the US elsewhere, I layer thoughts, readings, and reflections. I stage multiple returns.

****

Framing Return

Running through this experiment with montage, my argument is that return is a practice of listening to loss—one’s own and that of others. I propose that a practice of return illuminates some of the work required to be in the presence of others. In theorizing return as a way of listening to and hearing the catastrophic dimension, I attempt to nuance Hannah Arendt’s writing on political activity in the polis, which she attributes to the human condition, by emphasizing the ways in which a political subject makes herself seen and heard. Specifically, I am invested in a critique of the emergence of agency in particular spheres of appearance, here in the practice of testifying to loss or in the practice of mourning. Return, as a serial practice attentive to relationality, failure, and potential, animates the movement polyphonic listening requires.

In understanding the practice of return as a political process with radical potential, I center the histories and legacies of Palestinian survival, politics, and activism based in the righteous demand for and belief in the return (‘awdeh) of Palestinian refugees to homes and villages evacuated and destroyed by Zionist forces in 1948 and during the ensuing occupation. The material reality of this call for return and the imaginary that sustains it are twin aspects of a radical anti-imperialism that has sustained a people living seventy-one years of settler colonial occupation. The political sustenance provided by the demand for return is immense.

The Palestinian right of return (haq el ‘awdeh) to lands and homes occupied by Zionist forces, is singular; it cannot be another way. There is only one Palestine, there can only be one return to it. But what would it mean to take seriously the invocation “to have many returns”? I am not proposing a fracturing of this constant demand; nor am I questioning the right of the refugee. Yet, nesting within this singular demand, the possibility to have many returns invites us to think capaciously about the shuttling movements, the elasticity, and the imagination required to sustain political life. The possibility of having many returns also invites a multiplication of returnees and of journeys. If my loss is incommunicable, my declaration of rights is a silent scream. But if I and others return to this loss, if it is possible, as performance scholar Fred Moten suggests, “that mourning turns,” layers of loss, remembering, testifying open up as a potent invitation to listen.{13}

At the same time, in taking seriously the invocation to have many returns, I am also admittedly attempting to problematize the romance and orthodoxy around return in Palestinian political discourse and the cultural imaginary. I have also felt, as Abbas and Abou-Rahme themselves state as an impetus for their own work, “that the images coming out of Palestine (have) begun to stagnate, to deactivate rather than activate.”{14} In this, Abbas and Abou-Rahme draw attention to the extended liminal time heralded by the Oslo Accords—liminal because the promised sovereignty in those agreements has not materialized, liminal because of the relation with time (the Oslo generation) the term often evokes. In pulling the imaginative threads that have sustained this long, stalling wait for the materialization of a Palestinian dignity, Abbas and Abou-Rahme turn to history and to the future, layering visions of the present in order to ask for new ways to understand this contemporary wave of dispossession. I am inspired by, and mimic this question and this practice.

Not only the images but the words, the ideas, and the affects evoked to articulate a Palestinian future are increasingly out of joint: romanticized, fetishized, obsolete in a post-Oslo landscape.{15} In my attempts here to return to, and indeed to re-read, return, I propose a performative exploration of the communication of loss to loss. I attempt my own writing “from and through (an) interior.”{16} I oscillate between grief, anger, and mourning as a means of documenting the urgency for political elasticity.

****

One (Pain)

We have to keep looking at this so we can listen to it.

Fred Moten{17}

In perhaps the most classic example of performative mourning, of agency as enactment of and testament to loss, Antigone defies King Creon’s edict and buries her brother. In doing so, she asserts her bold humanity; her will to mourn the dead. The burial testifies to her grief and performs the injustice of the state, honoring the gods. Antigone is active, agentive, defiant. A classical political reading of her action understands Antigone as entering the polis, the space of political activity, emerging in so doing as a political subject. In burying her brother in defiance of the King, she transforms from a passive, private, princess to a defiant public threat.{18} In the actions she takes—burying the body and taking responsibility for having done so—lies a model of agency based on Hannah Arendt’s model for politics: “speech and action seen and heard by others.”{19} This reading offers tools to understand agency based on action: a politics based on noisy, visible activity. Antigone cries out: I loved my brother; his loss pains me—hear me, fellow citizens! I am grieving this injustice. Watch me bury him. Her actions move the chorus to empathic catharsis. We feel for Antigone, but we feel better that she has acted.

Zoom in to a different burial. In August 1955, 14-year old Emmett Till was visiting cousins in Money, Mississippi. Accused of whistling at a white woman, a group of adults shot the boy in the head, tied his body to a gin fan, and threw it in the river. His mutilated body recovered and returned to Chicago, the boy’s mother insisted on an open casket. Ms. Mamie Till Bradley’s decision to make sure that the whole world could see what a racist, white mob had done to her son asks for a different model of reading agency and politics.{20} Ms. Bradley says: friends and foes, I am grieving. I will bury my son, but first look what they did to him. My pain is greater than your discomfort at seeing this brutality. The funeral was attended by hundreds of thousands. And the boy’s broken, swollen head was photographed and disseminated in the black press, becoming legendary. The casket (and the wound) stay open. The boy is unburied. What does the mother’s quiet gesture ask of us?

The affective force of the funeral photograph is the subject of performance scholar Fred Moten’s haunting investigation of the sound of mourning. Instead of only looking at the photograph of the lynched black boy, the visual document of barbarity, Moten proposes to listen to it as well. This listening is necessary, Moten suggests, because it is impossible to look at the photograph and actually see Emmett Till. It is hard to see him, Moten claims, because Emmett Till, the boy, vanishes behind the brutality of the mob that lynched him. We miss the boy for the brutality. He explains, “if he seems to keep disappearing as we look at him, it’s because we look away.”{21} But this is precisely what the photograph demands that we do. The documented barbarity impels retreat while the boy’s mother holds the space open for return—the casket was left open.

In a piece Moten draws from, Elizabeth Alexander asks about the Rodney King videos: “can you be black and look at this?” There is a similar call and response here. In Alexander’s question, the mourning is there in the can you look? Therein lies the very recognition of the impossibility of seeing, of bearing witness, what Moten described as he keeps disappearing as we look at him, because we look away. There lies the testimony to the grief. There in the reluctance, the cringe, the disappearing as we look, the essential, necessary look away.

What can learning to listen to Emmett Till’s funeral photograph and Ms. Mamie Till Bradley’s burial teach us about return? Bradley’s politics of mourning underscores the urgency of return in political practice. Confronted with the will to destroy, expecting or performing action will not do. Retreat, stasis, hesitation, quiet is more like it.

Hartman is right to remind us, who is this mourning for? At an academic conference in New Orleans (that perennial capital of concurrent, cacophonous mourning), a professor I have never met asks me where my name is from. I tell him it is Lebanese. His face alights with the excitement of recognition. He begins to recount to me with zeal his first exposure to Lebanon during that country’s devastating civil war. With disturbing relish, he describes a photograph, printed on the front page of a national paper, of a man dragging a body with a knife in its back across a city street. I stand there, blinking in his sentences that won’t end. For whom is this empathetic action? Does our mourning ask for it? This sonic disparity is deafening. The difference between the silence in Alexander’s question (can you be black and look at this?) and the accelerated relish to relive the dragging of a backstabbed body.

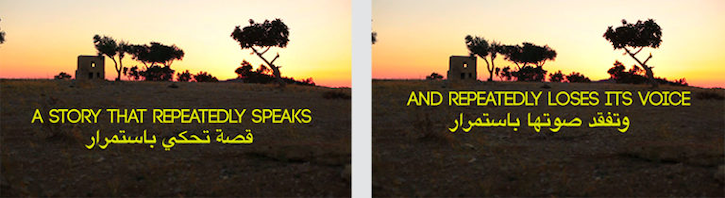

Figure 3: THE UNFORGIVING YEARS, PART TWO OF THE INCIDENTAL INSURGENTS, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme (2012-2013).

Figure 3: THE UNFORGIVING YEARS, PART TWO OF THE INCIDENTAL INSURGENTS, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme (2012-2013).

I am struck, driving the broken roads of southern Lebanon, by the ubiquitous martyrs’ posters commemorating fallen fighters in Syria, Palestine, and Lebanon. The dusty patches of earth blur with green shrubs and the smell of lemon blossoms. Faces fly past, young and unblemished, printed on party letterhead; swashes of green, yellow, red.{22} My own experience with them is always on the move, from a car window, or stealing glances while walking briskly over uneven sidewalks. Sometimes, I try to imagine how the streets of Brooklyn or Philadelphia would look were the martyrs to state violence commemorated in the same way. But in these East Coast US cities, the martyrs’ commemorations are slightly different: an occasional mural painted on a store side wall, each in its own colors. Yet, both kinds of commemoration share a similar ontology of mourning. If we listen to them, we hear a similar rhythm: defiant, celebratory. There are some traces of delusion in the twinkling of fallen eyes.

At talks and in organizing meetings, in books and online, the possible confluences and intersections of political actions take center stage. Arendt’s notion of second birth—the christened arrival of political subjects through the performance of public speech and action—fills the air. The promise of legions of Antigones defying clear edicts with equally clear actions hovers above. And even in the best of these, the proof of solidarity, of our intersectional politics, lies in the vocal actions we trace. Enthusiastic speakers tell of how, when tear gas canisters rained down on #BlackLivesMatter protests in Ferguson, Missouri in the summer of 2014, tweets from Gaza and Ramallah in occupied Palestine instructed distant sisters how to soothe burning eyes. Clear communication. Politics hailed as active solidarity: mediated speech, action seen and heard by others. Please understand: I want these pulls across and between communities, too. But I am stumbling where those urges are leaping.

Trace the resonances between the murals—painted with specific colors and lines on a single set of bricks—and the martyrs’ posters, painted with specific colors and lines, hanging over specific streets. Between the commemorations. I have suggested some aesthetic similarity, some shared ontology of mourning. But in tracing these performances of mourning we should ask: where is the cacophony of reaching out, the orgiastic action? Milk and soda for your eyes!/. . . throw the can back at them! Now, only silence; emptiness returns. Is an active political practice not possible here—not between the protesters, between the martyrs?{23} Between the grievers? I am looking for a form of commemoration in common that is not the impulse to build hierarchies of pain; not a search for originary violence.{24} But rather, a serial practice of return. Learning that the horizon must disappear as we look, because we turn away. Not the relish of recounting the photograph (to whom? for whom?)! Rather, following Mrs. Till Bradley’s command while listening to Saidiya Hartman: to hold open the sites of our destruction. Not to make them fetishes of suffering—not to prove blood quantum at each border crossing—but so that we learn to see the horizon disappearing. A different being with.

In Ghassan Kanafani’s iconic novella Returning to Haifa, the protagonist couple Said and Saffiya return to Haifa after twenty years of absence; twenty years since the Battle of Haifa on April 21, 1948, when a Haganah operation cleared the Arab neighborhoods of the city. For twenty years, the couple have been nursing the loss of home and a homeland. But they have also been mourning the loss of a son, presumed dead, whom they were forced to leave behind. When they return, they find their old house and the neighborhood, now inhabited by others. They also find their son, alive, raised by others. With this return comes a fresh pain, a new, more complete catastrophe, a different, living murder. In the novella, Kanafani produces a cry—a sound to accompany the nakba.{25} He deliberately pries open that catastrophe, saying with each paragraph: we have to keep looking at this so we can listen to it. This, too, is return. Not the movement of the couple from the West Bank to Haifa. The story is the return: holding the wound open, giving it sound. Hear: Mamie Till Bradley holding open the wound that swallowed Emmett Till’s boyish whistle. Polyphonic mourning.

****

Two (Anger)

I simply could not flip out.

Audra Simpson{26}I lose my temper, demand an explanation . . . Nothing doing. I explode.

Here are the fragments put together by another me.

Frantz Fanon{27}

In Moscow, on a layover on my way to Palestine the first time I attempted the most material kind of return, I felt a kind of physical pressure I didn’t understand. I was the last one to board the flight to Tel Aviv. When we landed, my breath was short, and I could feel my chest cavity moving under my shirt. Walking out of the plane and into the sparkling airport, everything echoed, as if we were underwater. Then, it was gone. They took my passport and gestured me off to wait. Soon, I found myself in a room with soldiers and their computers. A yellowing office with no windows, the desk corners peeling plywood. Everything in electric lights. So this was it, return. How banal!

In 2014, the same year I returned to Palestine for the first time, a fourteen year-old Palestinian boy was shot by Israeli soldiers while he was cutting class. Yusuf Ash-Shawarmeh and some friends crossed a piece of Israel’s separation fence, which arbitrarily cut through the boy’s family’s lands, to pick ‘akkub, an edible thistle. There was a hole in the fence, the boys slipped through it, picked the thistles. On their way back through the hole in the fence, their fists full of the edible plants, soldiers shot Yusuf. He died on the spot.

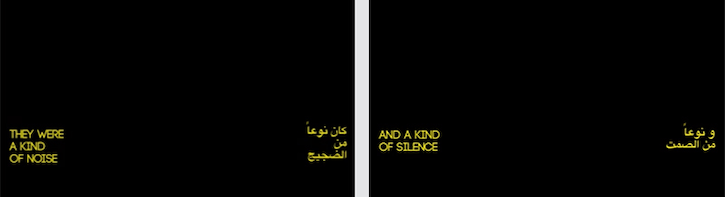

Figure 4: Framegrabs, ONLY THE BELOVED KEEPS OUR SECRETS, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme (2016).

Figure 4: Framegrabs, ONLY THE BELOVED KEEPS OUR SECRETS, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme (2016).

Only the Beloved Keeps Our Secrets is one of Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s recent video installations, one in which the technique of layering or montage palpable in their samples is quite developed. The installation explores Ash-Shawarmeh’s murder outside the town of Deir al-Asl, north of Hebron. The installation layers Israeli surveillance footage of the murder with archival footage of Palestinian dance and song, newsreel of protests and house demolitions in the occupied West Bank, and original music and field recordings. The artist statement accompanying the piece says that the video “weaves together a fragmented script.” In their words, the artists present “moving layers with images building in density on top of each other, obscuring what came before in an accumulation of constant testament and constant erasure.”{28} This constant testament and constant erasure is the rub that calls for return; that demands its constancy.

Only the Beloved Keeps Our Secrets is a moving meditation on belonging, destruction, presence, and absence. The layering of fragments implicitly acknowledges Fanon’s reflection on anger (Nothing doing, I explode: here are the fragments put together by another me.) And so the artists weave together a fragmented script in the angry wake of the boy’s murder. All the other mes watching and bearing witness, woven together.

Writing for Haaretz in the aftermath of the murder, the Israeli journalist Gideon Levy documented a charged exchange between the murdered boy’s father and a captain in the Israeli Defense Forces. The grieving father explained to the captain that the fields into which the boys had crossed were family lands; the boy was returning home. In response, the captain reportedly retorted: “you weren’t here<, and you don’t know what happened.”{29} The father, removed from his land, deprived of the right to work, and now robbed of a son is told by the commanding captain, you weren’t here. The remaining fragments of the man turn to Levy or to no one and say flatly, “they have taken everything.”{30} Watching the surveillance footage that Abbas and Abou-Rahmeh sample over minimal electronica, like a still roar of interference, I catch myself retreating. Just when I expect to cringe, at a gunshot or a confrontation, the footage cuts, another layer appears on top or behind it. But the montage only reveals more fragments, more disappearance; a dance form dying, an empty house, picked plants, waves retreating out to sea. As the rhythm accelerates, the demand to TESTIFY in red text in Arabic and English layered over the image of a boy’s fist full of thistles, draws out precisely the impossible bind of doing so. The duo’s layering of the surveillance camera footage with original text and dance and folklore asks questions about homeland, erasure, and destruction. Layering different documentation, it also invites us to think about the role of the documentary (footage, compilation, montage) in memory, testimony, survival, and mourning. The piece is a fascinating anthropology of documentation: it proposes a conscious technique of montage, in dialogue perhaps with anthropologist Michael Taussig —asking about the terror of disappearance—and with Moten, playing with strategies to hear the mourning of erasure.

ONLY THE BELOVED KEEPS OUR SECRETS, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme (2016).

“I realized,” Audra Simpson writes, “that ethnography in anger can have a historically and politically productive effect.”{31} In Simpson’s description of the US–Canada border crossing her, the disdain in the US border guard’s voice and the catty flippancy of her questions as she assumes and probes Simpson’s identity leap off the page. I want to spit at the woman she describes, too: “snooty, authoritative, aggressive—everything historically, politically, to dislike and to dislike with vigor.”{32} I remember their faces and their voices in the dingy room with peeling tables. The experiences at the border Simpson documents illustrate how Indigenous mobility enacts different sovereignties, exactly at the point of confrontation with the state. Simpson’s documentation and theorization of Indigenous border crossings emphasize how movement enacts ontology. This movement performs an understanding of history and law the state desperately tries to erase.{33} It is this very movement that makes the state desperate, anxious, afraid.

From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free! goes the chant in the streets of New York and London and Oakland. But in the streets of New York and London and Oakland, do we imagine that the Jordan River runs dry? While we chant, do we picture the buses to cross that riverbed divided into VIP and not VIP, split into lines marked for Europeans and lines marked for everyone else? Does this solidarity rhythm remember the eyes of teenagers with guns, hard and bright and bored? Does it register the absurdity of soldiers carrying lunchboxes? Let me return you to children enacting return, waiting in lines in the desert sun, somehow still managing to play, pushing and pulling on the railings that hold in and direct the border. In this hot, eternal mess of waiting, a woman sweating through her veil looks up and sighs, “all this for the Zionists?”

All of return is in her sigh. Her exasperated exhalation is sovereignty in motion. A potent political being. Spoken to no one, heard perhaps, but ostensibly ignored by sister, daughter, niece, fellow traveler. No one responds. Agency as exhalation in motion, just barely holding up on rough waves of anger and sadness, holding on to humor and insanity, holding—together with the fistfuls of thistles of teenagers cutting class—holding open. The chant wages the war of representation. It is clear enough to be a threat in some circles. But the sigh is for us; beloved and held close, holding retreating waves. It is a coherence cutting through the incoherence. An angry, still-moving clarity.

Now, zoom out from the West Bank border and hear oceans of sighs. A cacophony of holding open: not as speech and action. Polyphonic agency as anger in motion.

This crossing oceans to return from stolen land to stolen land does not make them interchangeable. Another being with is necessary. Another strategy to listen. In the same classrooms and political meetings where I fumble to testify to the denied humanity that threateningly crashes and washes, I start to hear others smarting. Have I just recounted with relish a photograph of a broken body I once saw in a national paper leaving someone else to stand there blinking? In the increasing relentlessness to document the losses I remember and those I do not, have I risked, at the same time, what Qwo-Li Driskill calls the “unseeing” of other, ongoing losses?{34}

As Fanon said, “we explode.” Folding out from the border, there in the meeting, suddenly, but again sifting through fragments: weaving silences, lost tempers, nothing doing. Again the heavy sigh of sovereignty in motion. Moving through the angry space of grief, as return.

****

Three (Loss)

We are losers. This, and this alone, will be my starting point.

Houria Bouteldja{35}

‘Akkub is tumble thistle in English. Gundelia. My mother has not cooked it, but I have tasted it. The desert sits funny with me, squinting at the horizon for some memory of the Jaffa sea, and the arid highlands of the West Bank feel dry and dusty and not like home at all. (I, who have returned, feign to admit it felt not like home at all!) And this is what Bouteldja must mean by being losers, we who have lost. Caricatures of home, of nations, of belonging, of victory. “They have taken everything,” the grieving father states, simply.{36} What if we start here, as Bouteldja asks? Actually let this be our starting point: what does it mean to hold onto and to hold open these losses?

In her exposé of the human condition, Arendt suggests that plurality is the foundational quality of political life. Plurality is the uniquely human quality of being together. And this being with, for Arendt, is the space to think about politics; plurality engenders the condition in which politics are possible. Arendt locates this plurality in the polis—that theoretical city-state that she imagines as the space of appearance. It is a space of appearance because it is here, Arendt writes, that individual human beings are reborn as political subjects with agency. This second birth happens when individuals perform speech or action seen or heard by others, transforming them into political subjects, and starting political processes over which they no longer have control. As mentioned above, Arendt’s argument has been criticized as an elitist vision of politics, wherein labor and work that take place outside of the polis are relegated to the realm of the apolitical.{37} I want to take from her critics this attention to visibility and appearance. And I want to take from Arendt the critical human condition of plurality: being with others.{38}

When the French-Algerian activist Bouteldja declares, in her chapter entitled, “We, Indigenous Women!,” that “we are losers,” she interpellates a particular plurality. By returning to a site of destruction—so many wounds, deaths, silences, and silencings—as a political birth (this and this alone will be my starting point), she calls for a plurality that imagines a being together not bound up in the performance of a particular speech; not connected to the performance of political agency. That is, her we is connected not by chants of angry defiance, but by the angry sighs of sovereignty in motion. As such, she asks for a place of listening, ephemeral and reverberating, and a practice of mourning.

Her impulse is perhaps in line with Douglas Crimp’s painfully astute observation, “for I have seen that mourning troubles us,” i.e. we refuse to do it; or we do so only performatively, asking for action, performing speech, desperate for a particular political agency. Without performative mourning, however, Bouteldja suggests a return to loss. By starting here, with loss, with the silent sighs, she holds space open even while oscillating between pains, moving between destructions, unearthing erasures. Boutledja’s return shakes out both nostalgia and spectacular mourning from the polis. In announcing a return that does not recover, she asks for a listening to loss that does not anticipate its end or its remedy. We are losers is a mourning that does not search for the origin of pain, it does not respond to Creon. It holds the casket open. More importantly, it is a holding open of pain that moves without hope. It is a turn that enacts plurality in total silence. No speech, nor action: plurality without appearance. We are losers: just being with.

****

Four (Yearning)

It is easier to be furious than to be yearning.

Audre Lorde{39}I’m still keeping secret what I think no-one should know. Not even anthropologists or intellectuals, no matter how many books they have, can find out all our secrets.

Rigoberta Menchú

Reviews of Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s work call it “nostalgic.” “OH, SEA!” the pink text screams in Only the Beloved Keeps Our Secrets. And the sea, in the West Bank, is precisely that horizon of longing, the impossible, geographic border, collecting the sighs of ruddy-cheeked teenagers who have never seen the red waves that lie beyond the checkpoints, walls, and fences. But Abbas and Abou-Rahme hold a similar suspicion of nostalgia and romance that Bouteldja draws on above, when she declares that loss is her starting point. The duo’s three channel installation The Incidental Insurgents demonstrates a particular development of both their affective relationship to an archive and what it might mean to sift through it in search of, in their words, “what we cannot see but feel is possible.” According to the artists, this installation stages an “unfolding” of a story of “a contemporary search for a new political language and imaginary.”{40} It follows two individuals, mirroring the artists themselves, as they search for politics, aesthetics, movement.

The piece is clearly reflective on the romance of resistance and rebellion and artistic insurgency in times of political change (it premiered in 2012, in the height of the Arab Uprisings). It explores the range of contradictory affects undergirding the search for new politics, including new frameworks of action, different discourse, and more immediate aesthetics. Critically, the artists build characters in this piece who become knowable in their lacks, in their absences, and in their contradictions. What makes them political characters is their movement on foot and in cars as they search for and, critically, fail to find politics.{40} What shapes their agency is not what they do or say—their speech and action “seen and heard by others.” The unseen narrator in Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s video montage calls it “a story that repeatedly speaks and repeatedly loses its voice”—whose protagonists were “a kind of noise and a kind of silence.” The agency of Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s characters is palpable in their affective relation to both past and future, their yearning. Their willingness to return, to find nothing there doing, to yearn. Active mourning.

Figure 5: Framegrabs from WHEN THE FALL OF THE DICTIONARY LEAVES ALL WORDS LYING IN THE STREET, PART THREE OF THE INCIDENTAL INSURGENTS, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme (2012-2013).

Figure 5: Framegrabs from WHEN THE FALL OF THE DICTIONARY LEAVES ALL WORDS LYING IN THE STREET, PART THREE OF THE INCIDENTAL INSURGENTS, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme (2012-2013).

What is it to be yearning? How hard is it to be yearning, to be yearning with? Yearning like the kites sent up by Palestinians over the militarized border fence in Gaza. It must be hard to be yearning with, otherwise it would be easy (and Lourde reminds us it is easier to be furious). On October 12, 2018, a Friday, during the Great March of Return, youth from Bureij refugee camp in Gaza tear down part of the separation fence, somehow remaking the coils of jagged barbed wire into the coils of telephone wire. In a clip since removed from the internet, a man tries to film the scene and, at the same time, assist in the efforts. He holds the camera and he reaches for the rope the youth are using to tear the wall down. Camera in one hand, reaching for the rope with the other. He goes for the rope, he touches it, he lets go; knowing he can’t actually do anything while filming, that his weight and his feet will be out of joint. He is caught here: to document or to throw down? To broadcast the movement, or to feel the tear of the rope into his palm? At one point he turns the camera to show his face and flashes us a victory sign—the rope pulling down the wall behind him, the clouds of smoke rumbling behind the rope. I’m not laughing at the citizen journalist, no. The seconds of his staged in-between layer the point. How to hold the rope and the victory sign at the same time?

****

Closing / Re-entry

In the forward to the recent volume Holocaust and the Nakba: A New Grammar of Trauma and History, the renowned Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury asks, “does the possibility of discovering a common vocabulary exist?”{42} He means to set the stage for a probing of the common affective, linguistic, and political ground between the two great catastrophes structuring life for most Israelis and Palestinians, the Shoah for the former and the Nakba for the latter. In a way, this has been my question, too; though I have not pursued a common vocabulary, per se. Rather, I chased a practice of listening, of rendering intelligible, that I attempted to theorize as a practice of return.

In a moving exchange with David Kazanian, Marc Nichanian tries to explain the urgency of understanding the impossibility of testifying to the catastrophic dimension that accompanied and drove the Armenian genocide. As part of that explanation, he examines the role of literature and translation in the documentation of disaster, returning to the paradox of witnessing. In so doing, he turns to the use by different Armenian authors of Herodotus’s story of the mute son of King Croesus. For years, Croesus tried to cure his mute son, to no avail. When Persians invaded the kingdom, a soldier came to kill the King. In that moment, the son cried out, attempting to save his father and overcoming his muteness. The soldier killed Croesus anyway, despite the formerly mute prince’s noteworthy protest. Nichanian writes of how the story figured as a prominent allegory for many nineteenth-century Armenian writers, grappling with Armenian struggles for liberation before the Turkish genocide. Nichanian accuses Armenian writers of misunderstanding the parable’s significance. He writes, “Literature is that scream crying out, which accompanies, for all eternity, the father’s death. Literature does not save the father! It saves the ‘disaster.’ Do you understand the difference?”{43} Thus Nichanian writes in no uncertain terms against what he calls an “optimistic view” of a politics of the future in the aftermath of genocide.

Still, it is hardly bleak nihilism that animates Nichanian’s argument. Rather, his is a moving entreaty asking us to think about agency beyond a politics of recognition and recovery—these necessarily couched in the language of the catastrophe, in the grammar of the victor. If we are convinced that the scream saves the disaster, we can be assured of the urgency of the testimony of the scream. Nichanian writes, “the only thing that remains to do is to understand what happened, to denounce our being in the grasp of the perpetrator’s will, always and again.”{44} How to do this, however? How to understand what happened? If the scream saves the disaster, what saves us?

I might return to Ursula Le Guin’s simple, crucial reflections about dreams with which I began. In The Lathe of Heaven, her exploration of the devastation of dreams—how they lead us astray, hurt us, mar the present, threaten to destroy the future—she offers: “often, it was not the apparently striking or salient element of the dream that was the effective one.” The dream is blinding, she seems to suggest. The search for action, the urgency to perform, the loud call to see, the chant, the promise—perhaps these are not the salient elements, nor the effective ones. Perhaps these are not what will save us. Instead, Le Guin asks us to consider those aspects of the dream that are less striking but very moving, nonetheless. That is, an affective aspect of the dream, an effective solidarity, a coherent co-presence, might not be in speech or action. It might lie instead in the practice, possibility, and invitation to return. Learning how to hear another’s destruction in holding spaces open. Being in the presence of others might then lie in how we look away and in learning how things disappear. In how we mourn. In our ability to imagine movement and momentum and weight; in our returns: multiple, myriad, large, minute. In our capacity to hold beloved secrets.

It is April again, and it indeed promises to be a cruel month. As I write, I wonder: what commemoration of the massacre at Qana this year, amid the global spread of a disease that has and will claim hundreds of thousands? I study again the photo of the Lebanese journalists documenting the massacre at Qana, looking for the eyes the man is hiding in his hands. I admit from here, in this April, I cannot even imagine a commemoration, a testifying to these losses, admittedly so different from the ones the photographers in the photograph tried to document. Overwhelmed, I stop. Some time later, I come back and try again to track the dirge’s polyphonic strains. I hear similar patterns, pauses, yearning. If I am still enough, I can imagine legions of us in similar refrains—starting, stopping, turning.

We will return, and the thought comes more like a sigh.

Title Video: The Part about the Bandits, Part One of the Incidental Insurgents / Only the Beloved Keeps Our Secrets / The Unforgiving Years, Part Two of The Incidental Insurgents

{1} Ursula Le Guin, The Lathe of Heaven (New York: Scribner, 2008), 36.

{2} This piece benefited from three sets of workshops. It started as part of the “Disidentifying Borders: Coalitional Futures and Migration” José Esteban Muñoz Targeted Research Working Session at the American Society of Theatre Research in 2018, convened by Dominika Laster and Hillary Cooperman. It subsequently benefited from feedback by participants in the Media Ethnography Lab at the Center for Advanced Research in Global Communication at the University of Pennsylvania in spring 2019, and that fall from the Indigenous Scholars Research Network at Wesleyan University. I wish to acknowledge in particular the feedback and encouragement of Yakein Abdelmagid and Joseph Weiss. Shortcomings I reserve as my own.

{3} Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” October 51 (1989): 16.

{4} Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014).

{5} David Kazanjian and Marc Nichanian, “Between Genocide and Mourning,” in David Eng and David Kazanjian, eds., Loss: The Politics of Mourning (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 131.

{6} Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self- Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

{7} Judith Butler, Antigone’s Claim: Kinship Between Life and Death (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 24.

{8} These reflections were encouraged by and echoed in Jodi Dean’s recent Comrade (New York: Verso, 2019).

{9} Jacques Rancière, “Who Is the Subject of the Rights of Man,” South Atlantic Quarterly 103, no. 2/3 (2004): 305.

{10} Kevin Quashie, The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2012).

{11} Jonathan Sterne, “Sonic Imaginations,” in Sterne, ed., The Sound Studies Reader (London: Routledge, 2012), 9.

{12} Tsing writes: “When I first learned polyphony, it was a revelation in listening; I was forced to pick out separate, simultaneous melodies and to listen for the moments of harmony and dissonance they created together. This kind of noticing is just what is needed to appreciate the multiple temporal rhythms and trajectories of the assemblage.” Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 24.

{13} Fred Moten, “Black Monin’,” in Loss, 65.

{14} Basel Abbas, Ruanne Abou-Rahme, and Tom Holert, “The Archival Multitude,” Journal of Visual Culture 12 (2013): 345-363.

{15} I have explored the explicit question of the political discourse of resistance in Palestine elsewhere, see Rayya El Zein, “Developing a Palestinian Resistance Economy through Agricultural Labor,” Journal of Palestine Studies 48 (2017): 7-26.

{16} Quashie, The Sovereignty of Quiet, 84.

{17} Moten, “Black Monin’,” 72.

{18} Butler, Antigone’s Claim.

{19} Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998), 58.

{20} Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 192–210.

{21} Fred Moten, “Black Monin’”, 65.

{22} I will not reproduce the extensive literature on these visual ephemera, their mobilization in war and peace, their capacity to commemorate, or the particular archive they create. See for example, Laleh Khalili, Heroes and Martyrs of Palestine: The Politics of National Commemoration (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009) or Zeina Maasri, Off the Wall: Posters of the Lebanese Civil War (London: I.B. Tauris, 2008).

{23} As Michael Taussig has put it, “the carrying over into history of the principle of montage.” Taussig, Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror and Healing (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), xiv. With my thanks to Edgar Garcia for this reference.

{24} I refer here to trends in Afropessimist literature that foreground an essential antiblackness in political violence of different types.

{25} Arabic for catastrophe; the word used to describe the events of 1948.

{26} Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus, 119.

{27} Frantz Fanon, Black Skin White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann (London: Pluto Press, 1986), 89.

{28} See the artists’ website for Only the Beloved Keep Our Secrets.

{29} Gideon Levy and Alex Levac, “‘It Was Nothing Personal,’ Bereaved Palestinian Father Told,” Haaretz, April 4, 2014.

{30} Quoted in ibid. “After having killed his son, Israel has now also revoked the entry permits the father and his other sons had so that they could work there. ‘Your permit is canceled,’ Walid, the eldest, was told this week at the checkpoint when he tried to enter Israel, where he worked in construction. His father’s permit was canceled too. ‘First they took my land, then they took my son and now they have taken my work. They have taken everything.’”

{31} Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus, 119.

{32} Ibid.

{33} Ibid., 115.

{34} Qwo-Li Driskill, “Doubleweaving Two-Spirit Critiques: Building Alliances between Native and Queer Studies,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 16 (2010): 79.

{35} Houria Bouteldja, Whites, Jews, and Us: Towards a Politics of Revolutionary Love (Paris: Semiotext(e), 2017), 103.

{36} See note 19, above.

{37} Rancière writes:“Arendt’s view (is) of the political sphere as a specific sphere, separated from the realm of necessity. Abstract life meant ‘deprived life.’ It meant ‘private life,’ a life entrapped in its ‘idiocy,’ as opposed to the life of public action, speech, and appearance. This critique of ‘abstract’ rights actually was a critique of democracy.” Rancière,“Who Is the Subject of the Rights of Man?”: 298.

{38} See also: Judith Butler, “Bodies in Alliance: and the Politics of the Street,” Transversal Texts, September 2011. My thanks to the blind reviewer for this reference.

{39} Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider. Berkeley: Crossing Press, 2007, 153.

{40} The Incidental Insurgents: The Part About the Bandits (Abbas and Abou-Rahme, 2012-2015).

{41} The duo write in their description of Part 2 of this piece, “Ironically these figures most clearly articulate the incompleteness and inadequacies in the political language and imaginary of existing resistance movements. Often desperately searching for a language able to give form to their impulse for more radical forms of action.” See https://baselandruanne.com/The-Incidental-Insurgents-Unforgiving- Years.

{42} Elias Koury, “Foreword,” in Bashir Bashir and Amos Goldberg, eds., The Holocaust and the Nakba: A New Grammar of Trauma and History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018), x.

{43} Kazankian and Nichanian, “Between Genocide and Mourning,” 140.

{44} Ibid., 142.