This should be a map or a diagram but it’s just a list

Cíntia Gil

[fragments of an imagined film festival]

**

In 2008 I traveled to London with friends, for four days, to show a short piece of film in the strangest of contexts. The days were foggy, and I thought I could not possibly stay for a fifth day, as the gray weather brought a heavy sadness over me. On the last morning, we went to the National Portrait Gallery, where a Richter exhibition was taking place. Two portraits stole my full attention. Soon they became obsessions. I returned home with postcards of them as talismans or reminders, and in the years to come I traded these two images for every kind of reason.

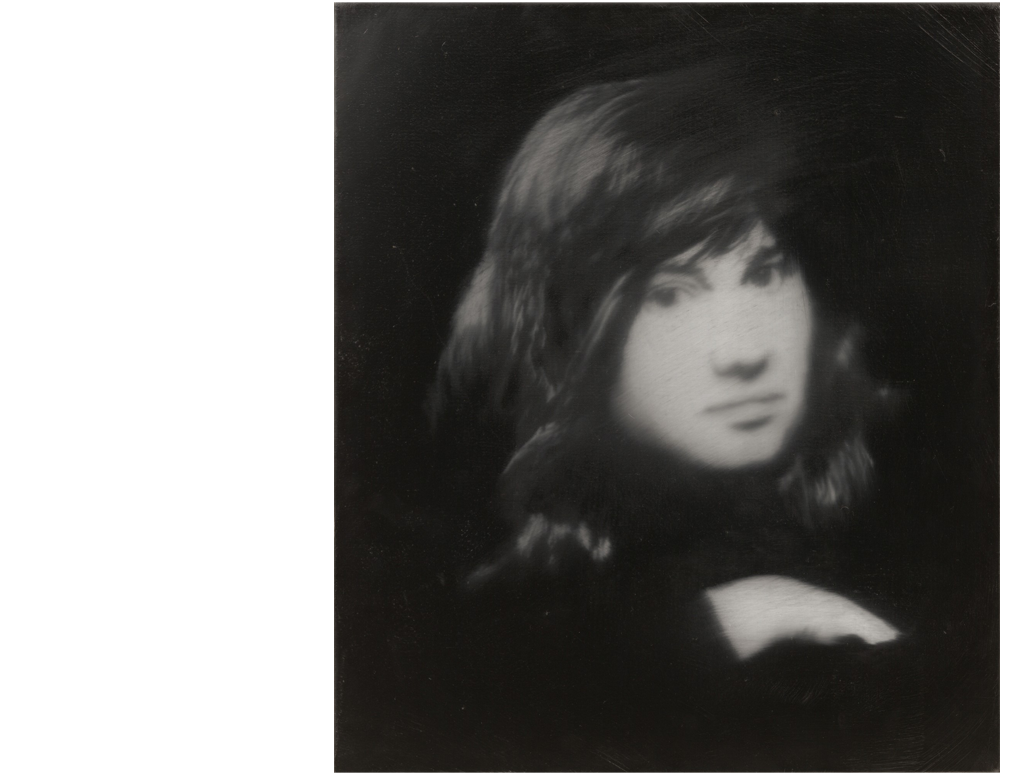

One is Youth Portrait [Jugendbildnis]—the portrait of a young Ulrike Meinhof made in 1988, from the series of paintings Richter had done of images taken from magazines depicting the fervor and tragedy of the Baader-Meinhof Group. But this particular portrait is unique: an almost classical female portrait of a certain straightforward sadness and interrogation, a suspended gaze suggesting almost a quiet acceptance of her place. I was nervous about a piece of hair, probably once held behind her ear, which looked like it was about to fall over her face and change her appearance forever.

The other one is Betty, a portrait of Richter’s daughter, also made in 1988. A blonde girl with a flowery red-and-white jacket looks toward the back of the painting that contains her—a dark, indistinct space which nevertheless accommodates the halo of her young skin, while her face remains hidden by her posture. What is she looking at? I realized she’s not looking at anything at all, but rather pointing at that obscure ground as a source of attention. It’s not about looking at. It’s about looking with her. I posted it on Facebook and stupidly called it “Film School.”

**

At the time, I was occupied with the idea of the contemporary. Is it more than a normative notion that helps us select, hierarchize, repress, and liberate what we recognize as belonging to our time? Is it more than a time produced by institutions, or an institutional time? Could it translate the experience of being together in time? What would that togetherness mean? I had been thinking about Agamben’s piece on the subject:

To perceive in the obscurity of the present that light that seeks to join us and cannot, that is what it is to be contemporary. That is why the contemporary is rare. That is also why being contemporary is, above all, a matter of courage: because it means to be able not only to fix the gaze on the obscurity of the epoch, but also to perceive in that obscurity a light that, coming in our direction, infinitely distances itself from us. Or even: to be punctual for a meeting that we can only miss.{1}

Could togetherness be figured outside of a capacity to grasp and dominate? And could I be contemporary with that portrait, where we see a girl named Ulrike who is dead and will die after becoming Ulrike Meinhof? Could she and Betty be together in time? Could that dark, obscure ground to which Betty is directed be their common? Could it be their immemorial past and simultaneously the matter of their becoming?

I guess that is why I used the term “Film School”—the experimental night that Jean Louis Schefer wrote about.{2} Could we learn that?

**

In 2011 I watched a film by Nathalie Nambot, Ami, entends-tu (Friend, Do You Hear, 2010). If I had to think of a film that made me want to be a programmer more than any other, I could say it’s this one (there were many others, but this one has a particular light that persists in my mind). In Russia, in a living room, an old woman speaks the words of Nadezhda Mandelstam, who saved the poet Osip Mandelstam’s writings by memorizing them. He wrote:

My age, my beast, who can

Gaze into your pupils

And with his blood cement

The vertebrae of two centuries?{3}

In the distance of time, I can still see the old woman’s face, the luminous aura of that room, the landscapes of a desolate Moscow. I hear that voice from the past made flesh, an absolute presence made possible by absolute absences and complicity. That film brought me Nadezhda, built a common place for us, shined on me a light of joy and warmth through the words of that woman who voiced her own time.

Nathalie Nambot wanted to film the woman who had translated Nadezhda’s work into French—this woman had memorized all the words of Nadezhda and offered them to the film. And Nathalie accepted them, understanding that she was actually filming Nadezhda. That was the dark, obscure background where Betty and Ulrike could be together, that experimental night where distant bodies coexist. Like Nathalie, Nadezhda, and me.

There was a man in the audience who cried and said, I never thought I would be able to see Nadezhda speaking and moving. There was a man who violently fired his anger at Nambot for being lied to, cheated—This is not a documentary! It’s a film.

Maybe film is this subversive operation of constructing a time and a space—a place of togetherness—where all that is virtual persists as shimmering light to be lived.

Now I knew I wanted to work at film festivals because of this togetherness—thank you, Nathalie.

**

There are two expressions that somehow make me very uncomfortable; often they are used to describe the capacity of film to perform some sort of justice or reparation in a system. These expressions are: to give voice, and to give visibility. I have tried to suspend my core disbelief in these expressions, and I have even looked for signs that it is misguided. I have tried to watch films that were acknowledged by a significant number of people for operating at the level of these expressions. Frequently, I left those films even more uncomfortable. Somehow the operation of giving voice or visibility was made possible by the operation of separating a voice, a visible existence from itself, from its own revolutionary echo—in order to be heard and seen onscreen, one is given the opportunity to exist as voice and image.

Isn’t this the opposite of what Richter was doing with Meinhof? Isn’t her portrait an expression of his encounter with her becoming in time, before and beyond the clichés that fixed her in the popular imagination, saving her from them and reconnecting a girl named Ulrike with Ulrike Meinhof, the woman who died in prison twelve years before Richter painted her?

**

In 2012, we programmed at Doclisboa a full retrospective of Chantal Akerman’s films. We decided to open with D’Est (1993). In her opening statement, Chantal spoke about her constant preoccupation with time—some films are not made to steal time from you, but rather to reconnect you with time (your time, from which you are bound to be separated, as if you could go through life without being aware of it). She said something like, In my films, I want people to feel time, not to steal it from them.

I thought that somehow she was revindicating another regime of visibility in film: one that was not about an attribution from the filmmaker to an object, but about a construction of a common between filmmaker and world—the common is time.

In Sud [South, 1999], a tree evokes a black man who might have been hanged. If you show a tree for two seconds, this layer won’t be there—there will just be a tree. It’s time that establishes that, too, I think.{4}

Can we abstract time from things and retain, or even recover, their political resonance? What is togetherness if not the construction of a commonality where what was separated can be reconnected? Is this not what we talk about when we talk about confronting systems of violence? Isn’t violence the symptom and operation of separating something or someone from themselves? Isn’t the present time a regime of separation of me from myself in time?

**

In Two Meters of This Land (2012), Ahmad Natche films one day in Ramallah, where a music festival is being prepared. Young people from different nationalities discuss and invent a place and a time, where the past can be recovered and escape its muteness.

On a hill nearby, the poet Mahmoud Darwish had been buried not long ago. In his long poem Mural, Darwish wrote:

Two meters of earth are enough for now.

A meter and seventy-five centimeters are enough for me.

The rest is for a chaos of brilliant flowers to slowly soak up my body.

What was mine: my yesterday.

What will be mine: the distant tomorrow,

and the return of the wandering soul as if nothing had happened.

And as if nothing had happened:

a slight cut in the arm of the absurd present.{5}

Natche’s film treats togetherness and place as instruments for opening the present, allowing the past to find its resonance in the now, and contemporaneity to stand as a question and a task—how do we build place now, when we exist separated from it? How do we break the continuum that speaks of our present, allowing the images of our past to complicate and inform an alternative time for us?

How do we invent a place to look our present in the eye and crack it—to see what escapes from it, what persists and resists, and interrogates us as being together in time. Shouldn’t community be seen as movement?

Isn’t this slight cut in the arm of the absurd present a mode of care? A mode of building community?

How can a film festival operate as such?

**

Darwish also wrote that Life on earth is the shadow of the unseen.{6}

Abderrahmane Sissako’s Life on Earth (1998) is a portrait of a community—of his father’s village, Sokolo in Mali, where life seems to unfold through the hours of the days in a continuous flow. Time is set by the light of the sun, and by men moving their resting chairs to follow the shade, as Sissako bikes across the village. The village becomes a repository for the imagination of place outside a Europe that is fearfully pulling itself together and proudly overestimating itself.{7} Away from Europe, the sound of the community radio brings ghosts of past and present—we hear the weather forecast for France, we hear about low temperatures and snow, while we see the burning sun of Sokolo.

The filmmaker writes: Do not fold your arms in the sterile stance of the spectator. For life is not spectacle.{8}

**

A boy carefully places chairs, one next to the other, in front of the wall in the West Bank, in Ramallah. They prepare a music festival.

[Metran men hada al-turab [Two Meters of This Land], Ahmad Natche, 2012].

The funeral of Mahmoud Darwish in Ramallah, 2008.

**

“Le chant des partisans” is the song of the French Partisans first recorded by Anna Marly in London. She also composed “La complainte du partisan” (The Lament of the Partisan), the song Leonard Cohen covered in 1969 as “The Partisan.”

Friend, do you hear

The black flight of crows

On our Plains?

Friend, do you hear

The deaf screams of the land

That it connects?Oh, the wind, the wind is blowing

Through the graves the wind is blowing

Freedom soon will come

Then we’ll come from the shadows

**

In 2015, Doclisboa programmed a retrospective called “I don’t throw bombs, I make films”—Terrorism, Representation. The title was taken from the theatrical release poster of Fassbinder’s The Third Generation (1979).

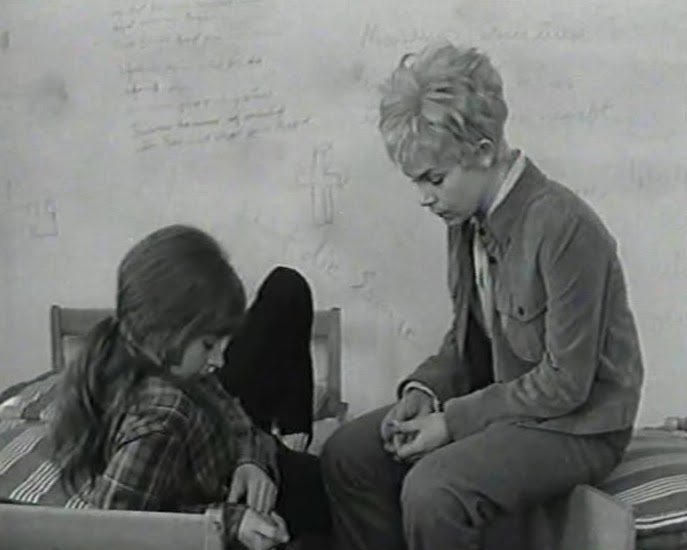

We screened Bambule: Care—Care for Whom? (1970), written by Ulrike Meinhof when she was a young journalist. The film was a TV production about a youth custody center where young girls were confined and disciplined. Mixing scripted scenes with documentary footage, the film expresses anger over conditions of exploitation, disrespect, and oppression inflicted on these girls. In the film, rioting is a liberatory gesture that brings some sense of hope but is crushed by the institution. All interactions with the institutional staff (especially men) are about violence and incarceration, including solitary confinement.

Bambule was buried in the archives of German television (ARD TV) for twenty-four years. Ten days before its original scheduled broadcast, Ulrike Meinhof went underground after freeing Andreas Baader from prison. There were fears of potential sympathy for Meinhof if the film was shown.

**

This photo was taken in October 2015, at the Cinemateca Portuguesa in Lisbon, after a screening of 3000 Houses (1967), the film made at the German Film and Television Academy Berlin by Hartmut Bitomsky, Harun Farocki, and Holger Meins (who also joined the Red Army Faction soon after shooting the film).

Six young people move through a city in order to establish the starting point of their joint action. But they can’t agree on the topic. In the end everybody goes their own way and leaves the city.{9}

The film was screened with Farbtest. Die Rote Fahne (1968) by Gerd Conradt, where a red flag crosses Berlin to be placed at City Hall.

In this picture, Bitomsky is explaining why he’s never been interested in the Conradt film. He’s talking about the difference between taking the center and exploring the periphery. How conceptions of power and action change between both, and how his preference for film over militantism was somehow related to that. I could have stayed for days, just listening to him.

The picture was taken by Dmitry Martov, and posted on Facebook. I carry it as a reminder.

BAMBULE: CARE—CARE FOR WHOM? [Bambule: Fürsorge – Sorge für wen?], written by Ulrike Meinhof, directed by Eberhard Itzenplitz, GDR, 1970.

BAMBULE: CARE—CARE FOR WHOM? [Bambule: Fürsorge – Sorge für wen?], written by Ulrike Meinhof, directed by Eberhard Itzenplitz, GDR, 1970.

**

PS Jean-Pierre Rehm has announced his departure from the directorship of FIDMarseille, after twenty years. I saw both Ami, entends-tu and Two Meters of This Land at that festival. But that is not why I write this note. Over the years, FIDMarseille created a space for solidarity and growth among film programmers and cinephiles. If there is a festival that questions cinephilia and its relation to our time, it’s that one. Attention—care—solidarity—community—reflection: qualities that I found in the programs but also in the way the team moved, talked, built occasions and places. I have never found so many opportunities to willingly change my mind—such a joyful activity, largely undervalued. One has to choose what to stand for, and Jean-Pierre gave me a certain strength to study the world and to choose my place within it.

Title Image: Gerhard Richter, BETTY, 1988.

{1} Translated by author. See also Giorgio Agamben, “What Is the Contemporary?,” in What Is an Apparatus? and Other Essays, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009), 47.

{2} Jean Louis Schefer, The Ordinary Man of Cinema, trans. Max Cavitch, Paul Grant, and Noura Wedell (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 10.

{3} Osip Mandelshtam, “Век [The Age],” From the Ends to the Beginning: A Bilingual Anthology of Russian Verse (website), ed. Ilya Kutik and Andrew Wachtel, trans. Tatiana Tulchinsky, Andrew Wachtel, and Gwenan Wilbur, accessed February 22, 2022.

{4} Chantal Akerman in Miriam Rosen, “In Her Own Time: An Interview with Chantal Akerman,” Artforum 42, no. 8 (April 2004): 122.

{5} Mahmoud Darwish, “Mural,” in Unfortunately, It Was Paradise: Selected Poems, ed. and trans. Munir Akash et al. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 161.

{6} Ibid., 155.

{7} These words paraphrase lines of poetry by Aimé Césaire. See Aimé Césaire, The Original 1939 Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, ed. and trans. A. James Arnold and Clayton Eshleman (Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2013), 23.

{8} See ibid., 17.

{9} Hartmut Bitomsky quoted in “3000 Häuser,” Doclisboa, accessed February 22, 2022.