The Making of The Making of . . .

Nida Ghouse

I’m just visiting this voice

I’m just visiting the molecular structures

that say what I am saying

I am just visiting the world at this moment and it’s on fire

It’s always been on fire

I’m saying this and it’s saying me

That’s how it works, seesawlike

The archive in the mouth and the archive is on fire

That’s the story

—Peter Gizzi, “Archeophonics”{1}

G

A scholar and a filmmaker encounter each other in an archive. They each first stumble on a trace—a name and a date—in the log of who accessed what material when, and then notice this evidence of the other having just been there over and over again in various files. As they crisscross each other in the same space of time, they are hesitant to assume that they share something, but of course they wonder. Even before they decide to meet in 2006, archival intimacy has arrived on the scene, amplified by the fact that no one else seems to have been in these documents since 1920.

This is the third possible beginning to the story. I’ve decided to foreground it for reasons I attend to at the end of this essay. Britta Lange and Philip Scheffner—the scholar and the filmmaker—recount their version of it in a text montage they published based on a lecture they delivered in 2007.{2} Centering on the question of how someone is made into a ghost, they lay out a cartography of changing perspectives in relation to the collaborative outcomes of their independent research in the Lautarchiv at the Humboldt University of Berlin, which took the form of The Making of . . . Ghosts, a multichannel sound and video installation. Lange came across the sound recordings held there in the autumn of 2002. Scheffner read about them in an article two years later. Lange was doing her doctoral research on life-size figures of so-called primitive people made during the German colonial period.{3} She was surprised to learn that voice recordings of captive colonial soldiers from the First World War were interned in the building.{4} Scheffner was on a trail of Indian biographies in Germany as part of a project funded by the European Union on cultural transfer between India, Germany, and Austria.{5} He did not know what was in store for him when he called up the archivist Jürgen Mahrenholz for an appointment.

The Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission was appointed by the Ministry of Science, Art, and Education on October 27, 1915, through the perseverance of Wilhelm Doegen, an English-language teacher in the imperial capital of Berlin who had “the idea of using the involuntary stay of the prisoners of war held in Germany for sound recordings of speech.”{6} The psychologist and acoustician Carl Stumpf, already the founder of the Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv (est. 1900), was entrusted with the leadership of this wartime research initiative, which “aimed to document the languages, dialects, songs, and music of the prisoners of war held in the German Reich.”{7} By the time its activities ended in December 1918, the commission had visited thirty-one internment camps based on the list of the War Ministry, and produced two—seemingly distinct—sets of recordings: 1,650 recordings of speech, song, and instruments on shellac discs for the purposes of linguistic research, and 1,031 recordings of music on wax cylinders for the purposes of comparative musicology.

In the following years, Doegen advocated for the establishment of an experimental phonetic institution—what he called a “talking library”—to consolidate the holdings of the Phonographic Commission and take form in a new sound department in the Prussian State Library. Stumpf refused the incorporation of the 1,031 music recordings into a department that aimed to focus on spoken idioms for teaching and researching languages, which he argued was not apposite to the musical, acoustic, and psychological scholarly investigations of the almost two-decades-old Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv. By 1920, the gramophone records found a home in the Lautabteilung, set up in affiliation with the State Library under the auspices of the Ministry of Science, Art, and Education, while the cylindrical records joined approximately seven thousand other musical holdings at the Phonogramm-Archiv, annexed to the Institute for Psychology at Berlin University and linked to what was then called the Museum für Völkerkunde and would later become the Ethnologisches Museum. These two sets of recordings made by the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission in internment camps during World War I have had separate trajectories in Berlin ever since. However, in 2022, just over a century later, both the Lautarchiv and the Phonogramm-Archiv that respectively hold these two collections were scheduled for relocation into the newly reconstructed Berlin Palace, site of the highly controversial Humboldt Forum. The two institutions and their collections are now housed there but will remain independently administered within the building.

Of the thirty-one prisoner-of-war camps that the scholars of the Phonographic Commission visited, the Halfmoon Camp in Wünsdorf near Zossen outside Berlin is a mainstay of this story. It was visited at least eleven times by about half the members of the commission: “They filled 482 discs with 765 individual recordings, which accounts for approximately 30 percent of all recordings in the [Lautarchiv] made under the auspices of Doegen.”{8} A special camp built for propaganda purposes, the Halfmoon Camp was where a concentration of mainly North African and South Asian colonial soldiers fighting for the French and British armies were interned. Initially built to house Muslim prisoners, it came to incorporate a subcamp called the Inderlager, where South Asians from different religious backgrounds were held. Attempts at political indoctrination using the language of jihad—following the diplomatic expertise of the amateur archaeologist Max von Oppenheim—largely failed. But while there was little defection to the German army, the camp was still a productive place, rife with scenes of epistemic extraction for the science of race—where songs and stories were separated from bodies, heads were cast in plaster, and anatomies were measured in (failed) attempts to prove ethnic homogeneity.{9}

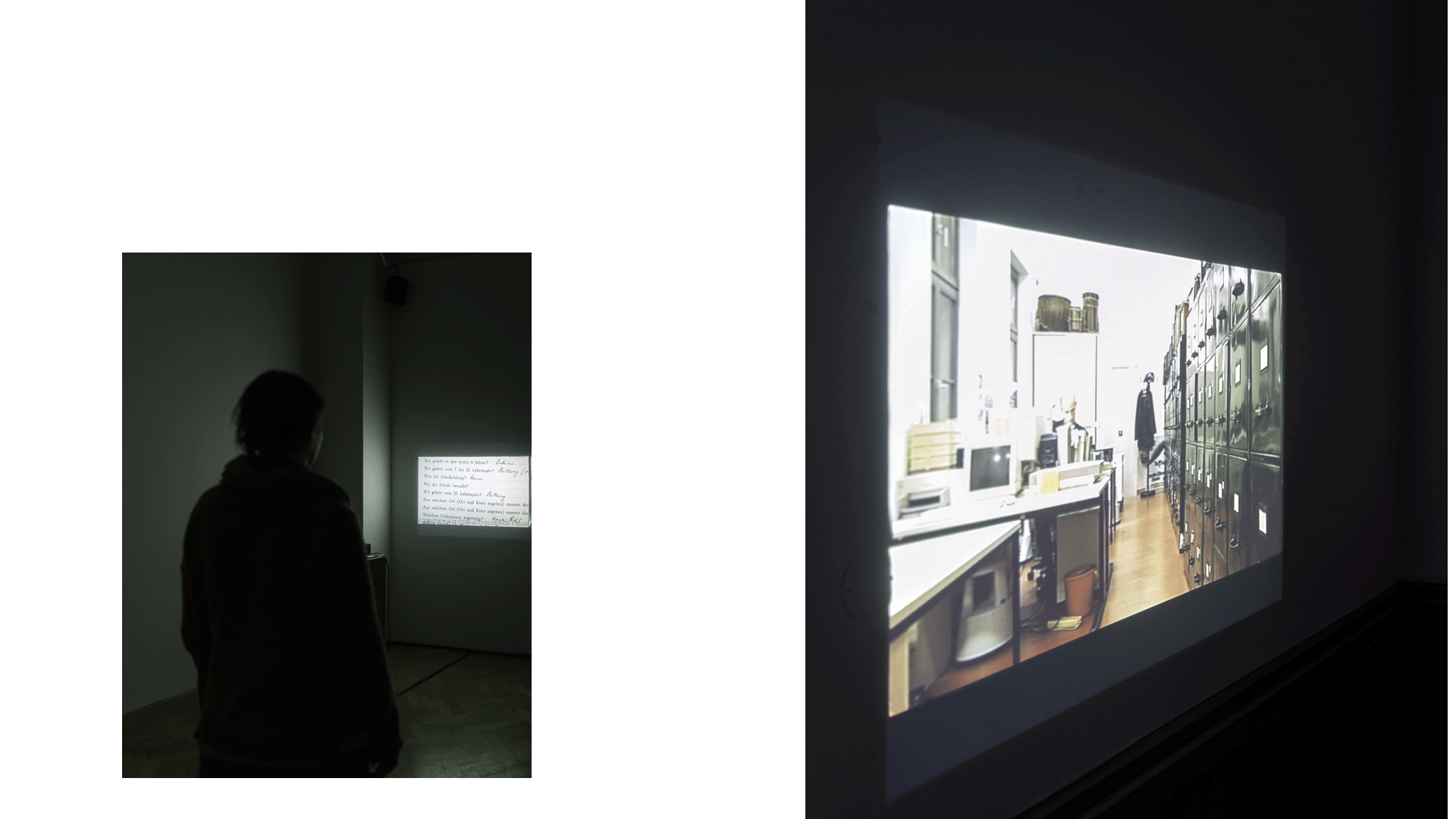

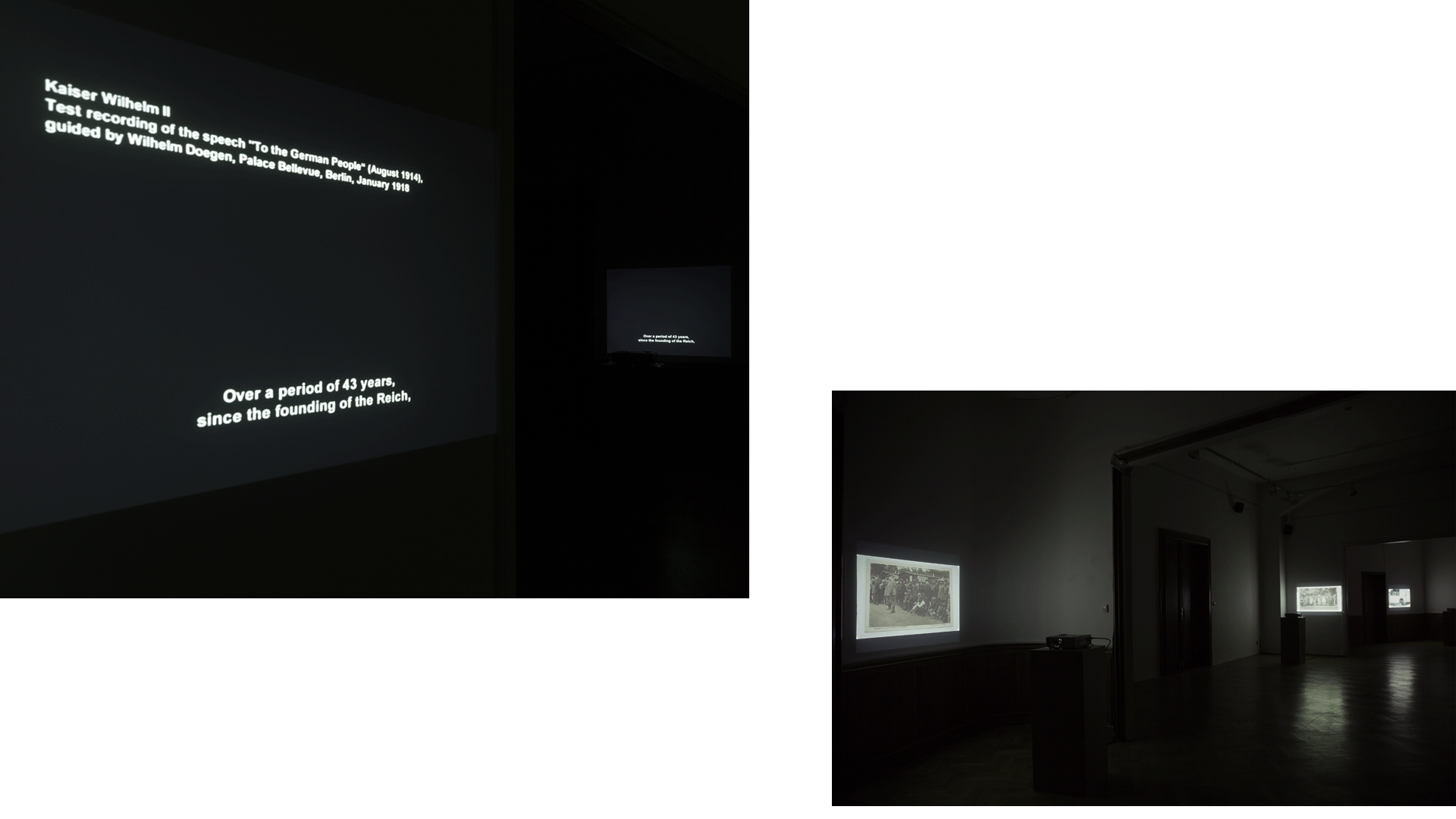

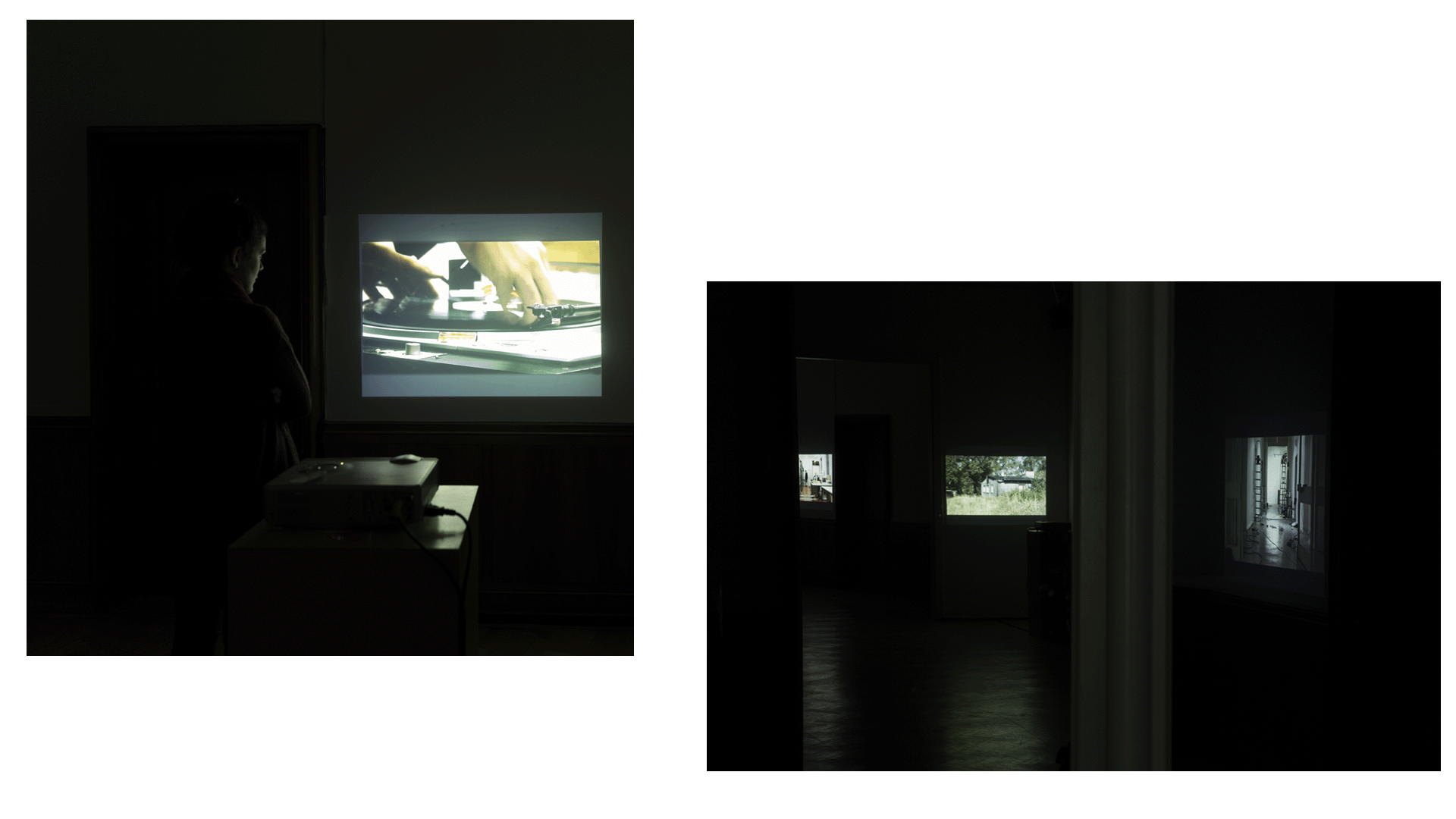

THE HALFMOON FILES: A GHOST STORY (Philip Scheffner, 2007).

THE HALFMOON FILES: A GHOST STORY (Philip Scheffner, 2007).

The 1,650 gramophone recordings produced by the Phonographic Commission came to comprise one of the founding collections of what is now known as the Lautarchiv at the Humboldt University of Berlin; today this collection remains the largest in the archive. Researchers have identified a total of sixty-five idioms in the recordings, including an array of South Asian languages, such as Hindustani, Punjabi, Bengali, Garhwali, Baluchi, Nepali, and Gurung.{10} Between 1999 and 2006, what survived of these holdings was digitized by the Hermann von Helmholtz Center for Cultural Techniques at the university, which is what made it possible for Lange and Scheffner to listen to the recordings when they arrived at the Lautarchiv in the early 2000s. Attending to a past they had not known existed, soon to be struck by a “small voice” singing in the big machine of history, the scholar and the filmmaker found themselves in the space of the archive as allies in the present.{11}

****

h

Soon after I walked into Philip Scheffner’s studio in Kreuzberg in the summer of 2020, I told him that I had been there before. It was while I was on a short visit in early 2013, my second time in Berlin. I had been researching the arrival of sound-reproduction technology to the Indian subcontinent and its implications for the status of the body for an exhibition I was working on at the time.{12} Through Scheffner’s film The Halfmoon Files: A Ghost Story (2007), Mall Singh’s voice had reached me as well—like a call across continents and centuries. This twenty-four-year-old Sikh soldier—from the village of Ranasukhi in the district of Firozpur in the region of Punjab, speaking his mother tongue into the funnel of a gramophone in 1916 from a prisoner-of-war camp in Wünsdorf—taught me that geography is something the body can carry. And sound, as we know, never stays in its place.

Was I to respond to this call across continents and centuries? And how exactly? As I recollected this earlier moment I began to wonder what it meant, if anything at all, that I had come to the studio once again for exactly the same reason as before, and that we were about to do exactly what we had done then—that is, play three video files across two computer screens, trying to manually start them all at the same time so as to have the time codes more or less in sync, such that I could get an impression of what Britta Lange and Scheffner had generated in bringing together their research material into a multichannel sound and video installation that took the form of an exhibition that I did not have the chance to experience in person.

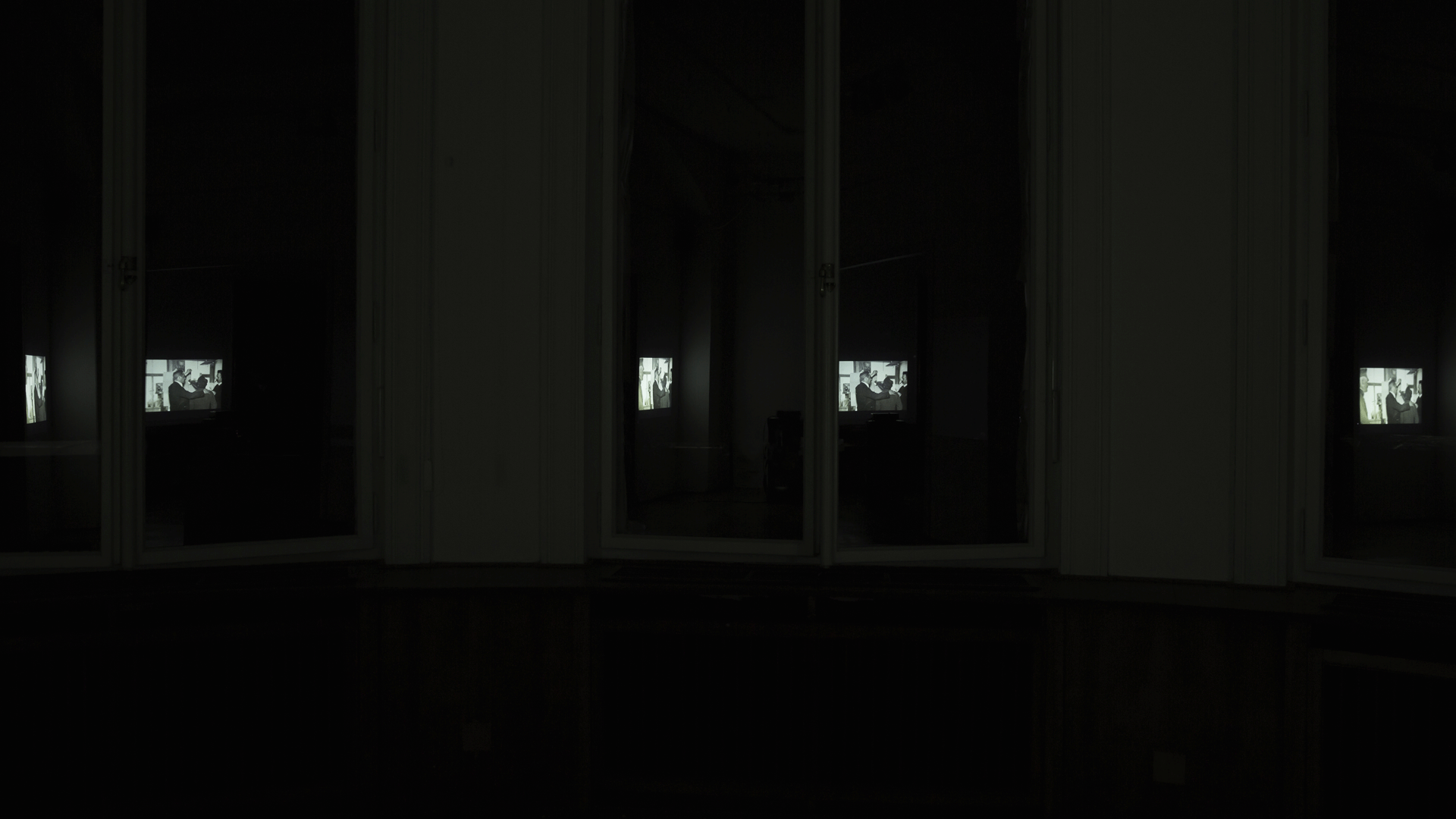

The Making of . . . Ghosts consists of four video projections. One contains only text and is silent. Each of the others is accompanied by sound specific to it, but the three tracks are edited, designed, and mixed to also function in relation, as a whole. There isn’t an A-to-Z narrative, is how Scheffner put it while setting the demo up for me; it’s more like wandering through a gallery space. The work is structured in a mimetic relation that anticipates the mode of its reception. Whether spread across the rooms and corridors of a space like Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien in Berlin, where the exhibition premiered in its original German version in 2007, or separated by partition walls within a large, empty warehouse, as in Project 88 in Bombay in 2011 in its English edition, the work is installed such that a viewer cannot stand in front of more than one moving image at a given moment. Multiple chapters, not necessarily announced as such, operate simultaneously. In each room the viewer is presented with different sets of archival or recorded materials, occasionally accompanied by voiceover, thereby opening up seemingly unrelated angles onto the same theme. The narratives can be followed independently or moved between, but they are very much constructed in juxtaposition. As a viewer stands facing one projection, sound and light from the other channels and screens flow and flicker in, sometimes corresponding—almost like audio dubbing—with what can be seen, all of it serving as an indication that there are other things going on that might be relevant. As long as one stays in the same position, this stuff will remain outside one’s field of vision. But listening could work—as everything can be heard.

I sat and watched all the channels at once.{13} In trying to keep up with them in parallel, I was confronted with the limits of my attention. Staying close to the complexity of any single thread necessitated my blocking out the others to a large degree. In my desire to register as much of the work as I could onto the surface of my being, I found myself caught in between, navigating the arguments implicit in the density and details of the historical research that comprised much of the content, and submitting to the dictates of the form to see what that produced in terms of an affective condition. With all the material right there in front of me, I got an impression of the whole, but I still don’t quite know whether one sees more or less of the work this way than when it is presented in space. And wasn’t that the point that Scheffner’s demo across his computer screens was making? That even when there is a multiplicity of perspectives being presented, what we perceive is determined by our position and intention toward them? And how is one to measure seeing or sensing more or less in any case? But perhaps I’m getting ahead of myself.

There are at least two questions on the table. The first is about the form of the work, and whether the mode of installation of The Making of . . . Ghosts—which entails a forced impediment to synchronously encountering the multiple channels of visual material—contains a proposition for the methods of history and for sound as a medium. The second is about my returning to the same place, for the same reason, at a different moment, and whether that’s relevant to The Making of . . . Ghosts in a specific way. What I mean is: Can a sonic capture be released? And what happens when it gets out? Or, to be even more explicit: Am I haunted?

****

o

In tracing the experience of South Asian soldiers held in internment camps in Germany during World War I, historian Ravi Ahuja finds “a state of fearful voicelessness” to be their shared condition.{14} While the affective registers he recounts range from comic relief to living death, and even extend to recalcitrant appropriation, nevertheless “the excruciating experience of social speechlessness and inaudibility” is what seems to have persisted across them. The basic problem the soldiers faced of not being able to communicate in a foreign tongue was compounded not just by the situation of wartime captivity but also by the racist hierarchies that governed German perception of the enemy’s non-European colonial troops that had ended up on German territory.{15} In her writings on the sound recordings made by the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission of Indian soldiers interned during the war, Britta Lange agrees that “the German language constitute[d] a threat, because the prisoner [was] subjected to its directives while not being able to understand it.”{16} In these circumstances, Ahuja contends, “achieving audibility was clearly one of the main objectives in the prisoners’ struggle for survival and mental sanity.”{17} But did they attain such a thing? If so, how did they do it? In which language? And who was listening?

If the question still is “Can the Subaltern Speak?” then the answer continues to be split. To follow literary scholar Santanu Das, the subaltern sings instead.{18} The subaltern “cannot—but, in fact, does—speak,” is how postcolonial theorist Rajeswari Sunder Rajan puts it. “‘Cannot’ in this context signifies not speech’s absence but its failure,” she claims.{19} Writing in 2011, Ahuja recounts as much: On December 8, 1916, a soldier by the name of “Chandan Singh, in a recording of a long and fascinating Punjabi folk tale, began his narrative with a short poem hinting at his experience of captivity in the Inderlager—apart from snow and wetness, the one sorrow he pointed out specifically was not being listened to.”{20} Lange goes further in pointing out the paradox: On June 6, 1916, a Gurkha by the name of “Jasbahadur Rai expressed that he did not dare speak [out of shame], and yet he did in front of the gramophone horn and in the presence of German researchers and technicians. Why?”{21} As Das writes, “These prisoners seem to have been muted in the very act of speaking.”{22} A disembodied voice is singing in Khasi that it did not have the audacity to say what it felt. A voice that has been recorded and that can be played back expresses sorrow at not being listened to. Even as the prisoners were being recorded—that is to say, even as they were being made to use their voices—their sense of social speechlessness did not go away. Moreover, Ahuja, Das, and Lange can hear this.

What is going on here exactly? First, what is audible to Ahuja, Das, and Lange is that the soldiers felt inaudible. What to make of this contradiction? Second, the fact that they felt inaudible is audible to researchers in the archive today, but it does not seem to have been audible to—or at least was not a concern for—the researchers in the camps back then. Is the temporal delay incidental or ancillary to this communication?

As scholars writing about a subaltern experience a century after it occurred, Ahuja, Das, and Lange are articulating for their readers a condition of inarticulateness not on the soldiers’ behalf but by way of listening to them. I use “listening” in its primary sense, in that the scholars both refer to the sound recordings made by the Phonographic Commission as source material, but also in an expanded sense of what listening to the past might mean. While the commission clearly “adhered to the objective of salvage ethnography: to document conditions [assumed to be] threatened with extinction or radical change,” listening to its epistemic output need not be governed by that same logic of loss and recovery.{23} While Ahuja’s, Das’s, and Lange’s archival intentions are oriented in some degree to the project of restoring subaltern subjectivity, the gap between “not being listened to” and that being heard points to other kinds of possibility. Whether or not it is conditioned by a sound recording in an archive, listening to and from that gap of inaudibility has the capacity to, as feminist scholar Anjali Arondekar writes, “restore absence to itself,” or at least demarcates a space from which to grapple with what that means.{24} If we can hear that the soldiers felt unheard, there is nothing to say we need to stop at that. What “the [sound] archive still promises,” then, is polyphony—a polyphony that, when taken seriously, invites us to listen beyond the semantic and the sonic.{25} It urges us to attend, on the one hand, to that which is extralinguistic and extra-intentional in what constitutes a voice, and, on the other, to the very insistence of the medium and materiality of sound itself.

Sound consists of a range of frequencies that extend beyond the threshold of audibility as it is generally conceived, to include that which can be felt. Reckoning with the medium and its materiality requires that we engage different modalities of listening, and this in turn has the potential to reconfigure the very relation between evidence and history. To be clear, and this is counterintuitive, my intention is not to privilege the medium of sound in the writing of history, but rather to consider how our engagement with sound archives—and with an ontology of sound as such—might compel us to realize that we haven’t been listening, and further, to more fully contend with what listening can be. That is, something we can do not just to sound but to images and objects, as well as to technology and matter at large.

****

With every drop of rain, the sea overflows.

We came to Germany on the orders of the British.

Listen, listen, we came on the orders of the British.

Three forces of water in a Nepali village.

Water flows ceaselessly.

Three forces of water in a Nepali village.

Water flows ceaselessly.

We are not dying, but even alive we are not living.

The soul is crying out.

Listen, listen, now listen to what I’m saying.

Like the bubbling water, my feelings bubble within me.

Can you assuage these feelings?

Listen, listen, now listen to what I’m saying.

For two paisa you can get a packet of Kaopalmar cigarettes, and light them with matchsticks.

On the other side in Hindustan, there is a beautiful mountain lush with greenery.

The love that existed will be stifled, my soul tells me.

Listen, listen, my love, my heart utters this with conviction.

Just as the flowers bloom in the yard, the heart blooms too and is happy.

The attack in the war of the fourteenth year; the world is shocked at the event.

It was summer; the atmosphere made it hot too.

Supply me at least with a fan for some air.

I do not wish to live in Europe, please get me back to India.

The Gurkha eat lamb and not duck.

We are of no use to the King of Belgium, neither alive nor dead.

s

Listening to a voice assumes the presence of a body. A voice that vibrates reminds the listener that “there is someone in flesh and bone that emits it.”{26} This voice has the capacity to carry sense, but is fundamentally that which exceeds it. Listening to “a voice as voice, as it offers itself in song,” or to a voice far away from home speaking its mother tongue, a language the listener—or the recordist for that matter—may not comprehend, is listening to “the pleasure this voice puts into existing: into existing as voice,” a pleasure it passes on.{27} When it comes from outside the realm of politics, from outside all of the signs that may have already been ascribed to the acoustic realm, song or speech such as this “brings the voice energetically to the forefront . . . at the expense of meaning.”{28} Singing serves as a distraction from the order of things, from the order of the archive, if you will—it “turns the tables on the signifier; it reverses the hierarchy.”{29} Even as a voice is singing of sorrow or speaking in pain—like the voice of a death-bound subject, for instance—there is something to be said that cannot be said of what it means to be listening to it. “Faced with [the sound of] the voice, words structurally fail.”{30} Listening to a voice doing what it does is listening to that which is “proper to [it], independently of language.”{31} It is listening to that which cannot be taken away.

****

t

Breathe in: the circumference of Mall Singh’s chest measured 920 mm on inhalation. Breathe out: 880 mm on exhalation. Somewhere amid the volume of those figures there was something of a voice.

In The Halfmoon Files, Philip Scheffner uses his own voice—in fact for the first time in a work—to listen. Through the use of dialogue and voiceover, he constructs and carves out a semibiographical/semifictional authorial position that functions as a resonant chamber not just for the archival material in the film—such as the sound recordings made of colonial soldiers held in Germany during World War I—but also for what it means for his own historical subjectivity as a German filmmaker to encounter that material as a colonial inheritance in the present. As a character, the voice of the filmmaker can be heard from outside the image and in conversation with someone who is in the frame: Jürgen Mahrenholz, the archivist responsible for overseeing the digitization of the Phonographic Commission’s record collection at the Humboldt University, or Amit Dasgupta, the Indian deputy chief of mission in Berlin who reads out Mall Singh’s words in a speech he delivers as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission replaces the stone commemorating South Asian prisoners—both friendly figures in administrative positions that enable and deny access accordingly.

Serving to propel the narrative forward, Scheffner’s voice performs itself. As a researcher, he goes through the motions of accessing these recordings at the Lautarchiv that no one seemed to have listened to for almost a century; as a filmmaker, he plays out the conceit of applying for the requisite permissions that never arrive to travel and shoot a film in India in search of a man who is now dead but was once recorded, who came from a village that does not appear to exist. A ghost story, to be precise. His interlocutors speak for themselves but also point to the archive, the university, the embassy, the nation—that is, to the place institutions such as these hold in the big machine of history. In juxtaposition, the small voice of Mall Singh, a captured soldier from the Halfmoon Camp, comes piercing through the crackle of a shellac disc, from a time that sounds like long ago and yet feels immediate:

There once was a man. He ate two ser of butter and drank two ser of milk in India. He joined the British Army. This man went into the European war. Germany captured this man. He wishes to go to India. He wants to go to India. He will get the same food he had in former times. Three long years have passed. Nobody knows when there will be peace. In case this man is forced to stay here for two more years, he will die. If God has mercy, he will make peace soon and this man will go away from here.

Mall Singh spoke these words in Punjabi and into a phonograph funnel at 4 p.m. on December 11, 1916. The recording lasted one minute and twenty seconds and is registered in the archive with the number PK 619. What he said that day—translated into English with the help of Rubaica Jaliwala and subtitled onto the film—is now a much-quoted passage in the literature that has emerged since the release of The Halfmoon Files.

Like the filmmaker, the soldier is not to be seen in the film. In all of the research that Scheffner conducted, he did not find a photograph of him. Instead Mall Singh can be heard speaking his mother tongue in the third person from beyond the realm of the image, from the edge of history. The absence of a visage stands in for both a political refusal on the part of Scheffner and an epistemic preconfiguration of the archive’s inability to fully recover a person.

A film from 2007 attends to a recording made in 1916—The Halfmoon Files is a labor of listening. An ethical imperative persists even in the face of the impossibility of historical justice. It summons the voice-as-listener onto the stage, which is a stage for an encounter with an earlier time as well. As a narrator, the filmmaker imparts factual information about the multiple contexts—the prisoner-of-war camp, the Phonographic Commission, the sound archive—that the film is navigating, both past and present, but his voice is not neutral: he speaks with a tone and an accented English. At one point the narrator exerts his judgment: “The scientists working at the camp are not interested in personal stories”—that is, the researchers did not listen to what their subjects had to say. If they were listening, they were listening to something else. As Britta Lange explains, “It was not the content of these texts as such that interested the linguists; their aim was rather to attain examples of spoken language.”{32} As a scientific enterprise, the commission’s aim was clearly defined: “According to Doegen, the task of the Phonographic Commission appointed in 1915 consisted in ‘systematically recording on sound discs the languages, the music, and the sounds of all the peoples residing in German prisoner-of-war camps according to methodological principles and in relation to accompanying texts,’ and hence to document the different languages and dialects as audio recordings, phonetically, and in writing.”{33} The recordings were meant only to supplement the text. By listening to Mall Singh’s voice-as-voice, Scheffner’s film restores sonority to the site of history.

The surface of sound holds both times, brings them onto the same plane. And yet, “alive and bodily, unique and unrepeatable,” Mall Singh forms “a relation with another unique existence”—that is, Scheffner’s. Listening to Mall Singh in The Halfmoon Files, “we find ourselves inside a message.”{34} One time touching another, the presence of an absence felt. And isn’t that what haunting is?

****

s

So whose story is this? In an essay titled “Sensitive Collections,” in which she addresses the difficulty of what is to be done with body parts, objects, audio clips, visuals, plaster casts, and measurement data, Britta Lange recounts a scenario in which restitution comes to naught. In 2002, a man who had been the subject of a 1942 anthropological study surveying 105 Jewish families in the Tarnów ghetto in Poland receives a copy of a portrait photograph of his younger self, accompanied by a standard data sheet of measurements that had been taken of his eleven-year-old body. He returns the piece of paper to the Museum of Natural History in Vienna with the words “That is your story.”{35}

The initial prompt for this essay—which came a few years ago from film theorist Nicole Wolf—was The Making of . . . Ghosts, the multichannel sound and video installation that Lange and Philip Scheffner produced together. By foregrounding the way in which the scholar and the filmmaker found each other through the metadata of the archive—that is, not through the content of the archive, but through their own traces within it—over the other possible beginnings they mention, I wanted to draw focus to the particular conditions from which their collaboration emerged. By returning to the opening, now at the end of the essay, what I also want to delineate is that their encounter at the site of the colonial archive has had implications not just for the work they went on to produce from it, but also for my own writing about it, which I am still grappling with. Whose story is this?

The specific terms of engagement with the sound recordings in the Lautarchiv that Lange’s and Scheffner’s initial forays put into play have influenced the creative and scholarly output that has emerged from the archive since. This much has already been observed with regard to The Halfmoon Files, the award-winning documentary that Scheffner released prior to The Making of . . . Ghosts. In her recent publication Captured Voices, Lange herself explicates:

The engagement with the personalities and biographies of the speakers, their origins and the situation in the camps, as well as the question of what they actually said was set into motion not by an academic but by an artistic project. . . . [Scheffner’s] questions were transferred to scientific papers, which on the one hand further researched the historical context of the involved groups of speakers of certain languages or from certain regions of origin. On the other hand, the scientists also began to examine individual recordings from historical and cultural studies perspectives for the content of what was said or sung, for its genre and for everything that was recorded and can be heard besides speech and song.{36}

In another recent publication, titled Absent Presences in the Colonial Archive, cultural historian Irene Hilden presents science historian Jochen Hennig’s insights on how The Halfmoon Files “set in motion a crucial shift towards a critical awareness and postcolonial appropriation of the Lautarchiv’s material. On the one hand, the film considered the recorded speakers and singers as historical subjects and not as mere representatives of a certain language or dialect. On the other hand, the film prompted a growing awareness of the fact that the sound collection should be located within current postcolonial discourses in Germany and beyond.”{37} Suffice to say, The Halfmoon Files occupies pride of place not only by virtue of being the first project in the contemporary context to bring material from the Lautarchiv into the public realm, but moreover because of its paradigm-shifting status as a film whose single-screen digital format enabled its circulation in scholarly milieus conducive to its reception.

Addressing the relation between the film and the much less traveled and exhibited installation invites a consideration of the methods of history and the matter of narrative with which the two forms contend. Thinking across the individual and collective authorship of these productions brings into focus the notion of inheritance. Whose inheritance is the colonial archive, if you will? To whom do the sound recordings made by the Phonographic Commission belong? And what is to be done with them? What of this inheritance can be shared by someone—like me—whose engagement remains mediated by the film and the installation in question? Conversely, what of my inheritance does this mediation interrupt or impede? These works are worthy of the influence they have had, and I too am indebted to them—this I do not deny—but whether or not the particular mode of addressing the archive that they set into motion is necessary to maintain, I am not certain. Perhaps the point I am making is indicative of nothing more than the protracted significance these works have, even for approaches not yet taken that will eventually find themselves compelled to break away from them. Moushumi Bhowmik’s “incomplete listening” (which finds Keramat Ali to be a soldier) and Irene Hilden’s “failed listening” (which finds him to be a sailor) point in such directions.{38} Perhaps going through these very motions of thought and affect is imperative for another positionality toward the archive, as well as the voices in it, to come into being. Who is the ghost here? And who is haunted?

Title video: The Making of . . . Ghosts (Philip Scheffner, Britta Lange, 2007).

{1} Peter Gizzi, “Archeophonics,” in Archeophonics (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2016), 1. I thank Alexander Keefe for sharing this poem with me.

{2} Britta Lange and Philip Scheffner, “‘The Halfmoon Files’: Text montage based on a lecture (2007),” trans. Marcie K. Jost, transversal, July 2008.

{3} Britta Lange, Echt. Unecht. Lebensecht: Menschenbilder im Umlauf (Berlin: Kulturverlag Kadmos, 2006).

{4} Britta Lange, Captured Voices: Sound Recordings of Prisoners of War from the Sound Archive 1915–1918 (Berlin: Kulturverlag Kadmos, 2022), 17.

{5} See Merle Kröger, “IMPORT EXPORT: Cultural Transfer between India, Germany, Austria,” Events, Connections, July 8, 2005.

{6} Wilhelm Doegen, “Denkschrift über die Errichtung einer LAUTABTEILUNG in der Preuss. Staatsbibliothek” [Memorandum on the establishment of a sound department in the Prussian State Library], Berlin, November 1918, quoted in Britta Lange, “Archive, Collection, Museum: On the History of the Archiving of Voices at the Sound Archive of the Humboldt University,” Journal of Sonic Studies 13 (January 2017).

{7} Lange, “Archive, Collection, Museum.”

{8} Jürgen K. Mahrenholz, “Recordings of South Asian Languages and Music in the Lautarchiv of the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin,” in When the War Began We Heard of Several Kings: South Asian Prisoners in World War I Germany, ed. Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau, and Ravi Ahuja (New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011), 198.

{9} For more, see Philip Scheffner’s film The Halfmoon Files (2007).

{10} Heike Liebau, “A voice recording, a portrait photo and three drawings: tracing the life of a colonial soldier,” ZMO Working Papers, no. 20 (2018): 5.

{11} I allude here to Ranajit Guha’s The Small Voice of History: Collected Essays, ed. Partha Chatterjee (Ranikhet, India: Permanent Black, 2009), which I arrived at via Anand Vivek Taneja’s Jinnealogy: Time, Islam, and Ecological Thought in the Medieval Ruins of Delhi (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2017).

{12} That exhibition became La presencia del sonido, at the Botín Foundation in Santander, Spain, 2013, cocurated with Núria Querol.

{13} Three—minus the silent text track—when at the studio, and four when at home.

{14} Ravi Ahuja, “Lost Engagements?: Traces of South Asian Soldiers in German Captivity, 1915–1918,” in Roy, Liebau, and Ahuja, When the War Began, 25.

{15} Christian Koller, “German Perceptions of Enemy Colonial Troops, 1914–1918,” in Roy, Liebau, and Ahuja, When the War Began, 130–48.

{16} Britta Lange, “Poste restante, and Messages in Bottles: Sound Recordings of Indian Prisoners in the First World War,” Social Dynamics 41, no. 1 (2015): 12.

{17} Ahuja, “Lost Engagements,” 42.

{18} Santanu Das, “The Singing Subaltern,” parallax 17, no. 3 (2011): 4–18.

{19} Rajeswari Sunder Rajan, “Speaking of (Not) Hearing: Death and the Subaltern,” in Can the Subaltern Speak?: Reflections on the History of an Idea, ed. Rosalind Morris (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 112, quoted in Das, “Singing Subaltern,” 5.

{20} Ahuja, “Lost Engagements,” 42.

{21} Lange, “Poste restante,” 12.

{22} Das, “Singing Subaltern,” 4.

{23} Lange, “Archive, Collection, Museum.”

{24} Anjali Arondekar, For the Record: On Sexuality and the Colonial Archive (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), 1. I thank Anurima Banerji for first pointing me to this argument.

{25} Arondekar, For the Record, 1.

{26} Adriana Cavarero, For More than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression, trans. Paul A. Kottman (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005), 4.

{27} Italo Calvino, “A King Listens,” quoted in Cavarero, For More than One, 4.

{28} Mladen Dolar, A Voice and Nothing More (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 30.

{29} Dolar, Voice and Nothing More, 30.

{30} Dolar, 13.

{31} Cavarero, For More than One, 13.

{32} Lange, “Archive, Collection, Museum.”

{33} Lange, “Archive, Collection, Museum.”

{34} John Berger, “Some Notes on Song: The Rhythms of Listening,” Harper’s Magazine, February 2015. I thank Haytham el-Wardany for sending me this essay right when I needed it.

{35} Britta Lange, “Sensitive Collections,” in Crawling Doubles: Colonial collecting and affect, ed. Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc (Paris: Éditions B42, 2016), 314.

{36} Lange, Captured Voices, 19.

{37} Irene Hilden, Absent Presences in the Colonial Archive: Dealing with the Berlin Sound Archive’s Acoustic Legacies (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2022), 76.

{38} Moushumi Bhowmik, “Incomplete Listening, Unfinished Writing: Sound and Silence in Archival Recordings from the Early Twentieth Century,” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 44, no. 5 (October 2021): 1000–1015; and Irene Hilden, “Failed Listening,” ch. 3 in Absent Presences, 61–94.