The Accidental Outside

Genevieve Yue

For certain types of films, festivals are an end in and of themselves. This is especially true of experimental film festivals and, within the past fifteen years, experimental documentary film festivals. Such venues offer few commercial off-ramps: there is little to no hope of a licensing deal following the festival, and while some bigger titles might get a museum or microcinema event, the short year that a film travels the festival circuit is likely the only time many films will ever screen publicly. At these festivals, a filmmaker may connect with funders on the strength of a previous film, or a critic may take note of a new work in their festival report. In an ideal situation, the filmmaker will then leverage this support to burnish their CV, write grant applications, and, if also employed in the university system, bolster their case for tenure and promotion. They will make new work, to screen at the following year’s festivals, and the cycle repeats.

Despite the limited horizon of experimental documentary festivals, there has been a remarkable proliferation of these events in recent years. This has occurred within a broader increase, beginning in the early 2000s, in all types of film festivals, including those solely devoted to documentary. In this span, the even more niche area of experimental documentary grew at all levels: many experimental documentary festivals were conversions of preexisting festivals, while others were fortified sidebars at established festivals.{1} Dozens more were newly invented, including a first wave in the 1990s; then a flurry in the early 2000s; followed by a smaller but still substantial group into the 2010s and later.{2} There were also a number of non-competition series that began during this period, such as Doc Fortnight (est. 2001) at MoMA, and Art of the Real (est. 2013) at Film at Lincoln Center.

The term experimental documentary is fraught, and I use it only provisionally. Undeniably, it raises a host of objections, some of which are inherited from twentieth-century avant-garde film, which rejected both experimental (unserious and amateurish) and documentary (too conventional a framework for describing formal innovation) as descriptors. The alternatives that have arisen in the names of festivals and programs—among them nonfiction, art of the real, artist film, and avant- or post-doc—raise new problems as they resolve the old. Indeed, it is a well-established tradition among avant-garde scholars to bemoan the inadequacy of terms like avant-garde and experimental, and for anyone invested in transgressive, radical filmmaking, a tidy fit into any category, much less one called experimental documentary, is just as discomfiting.

INVESTIGATION OF A FLAME (Lynne Sachs, 2001), which was featured in the Museum of Modern Art's inaugural Doc Fortnight program.

INVESTIGATION OF A FLAME (Lynne Sachs, 2001), which was featured in the Museum of Modern Art's inaugural Doc Fortnight program.

Rather than entering into the debates around terminology, I am interested in examining the tension within the phenomenon of experimental documentary between its claims to radicalism and the institutional and material conditions, namely, the film festival, that shape it. In this, experimental documentary inherits various long-standing debates within avant-garde film, including the debate over how aesthetic and political radicalism, inherent in the avant-garde’s very name, can be reconciled with each other, and over the degree to which institutional and industrial supports compromise the avant-garde’s autonomy.

To the extent that experimental documentary can be recognized as a salient mode of practice, circumscribed within the space of international film festivals, it allows us to think through these questions differently, because its unique bounded structure provides an opportunity to understand how such films are made, selected, and seen. Traditionally, avant-garde film, and indeed much of film history generally, has been approached by scholars and critics through textual analysis. While I am indebted to the method of close reading, I shift my emphasis here to the self-contained culture and conditions of making and viewing, a reframing that provides a different view of the relationship between institution and art. How does the social existence of a film, especially as something that exists among many other, likely similar films, shape what Annette Michelson called its “radical aspiration”? To answer this requires approaching experimental documentaries not only as richly signifying texts, but as complex cultural and material objects that travel from city to city on hard drives, film reels, and downloaded media files, to be projected on all manner of screens, and finally discussed and debated in ephemeral conversations and published criticism. This limited arena of circulation makes visible what are often overlooked relations between material conditions of production and claims to radicality.

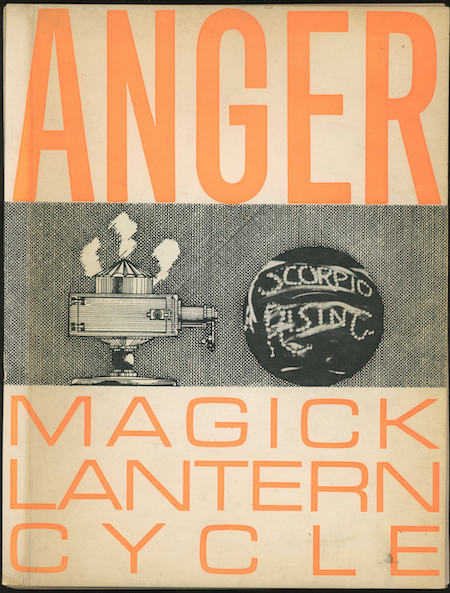

MAGICK LANTERN CYCLE program presented at the Film-Makers' Cinematheque in spring 1966. Later that year, Annette Michelson would write: "Many of our best independent film-makers, such as Kenneth Anger, Robert Breer, Peter Emmanuel Goldman, Jonas Mekas, Shirley Clarke, are committed to an aesthetic of autonomy that by no means violates or excludes their critical view of the society in which they manage, as they can, to work."

MAGICK LANTERN CYCLE program presented at the Film-Makers' Cinematheque in spring 1966. Later that year, Annette Michelson would write: "Many of our best independent film-makers, such as Kenneth Anger, Robert Breer, Peter Emmanuel Goldman, Jonas Mekas, Shirley Clarke, are committed to an aesthetic of autonomy that by no means violates or excludes their critical view of the society in which they manage, as they can, to work."

For what it’s worth, I still believe in film’s radical aspiration, even if I (like Michelson herself) hold many reservations about its viability. As Abby Sun has recently argued, “If the purpose of programming and exhibiting subversive films is to undermine systems of cultural power, one way to do so is by awakening us to our unwitting complicity with these institutions, and offering a model for escaping them through non-commercial production and circulation practices.”{3} I am less hopeful than Sun about the possibility of escaping “unwitting complicity,” but I share with her the conviction that self-awareness is fundamental to any kind of radical project. If cinema is to be politically revelatory, then it must keep its eyes fully open, including to the contexts of its own production.

While there are few off-ramps from experimental documentary festivals, on-ramps are plentiful. Generally speaking, film festivals are attended by the people directly involved in their production, namely filmmakers, programmers, and critics. Though different festivals will make more or less of an effort to engage a local audience, experimental documentary festivals often cater to their own constituents. By and large, experimental documentaries are not widely available outside of these spaces, a sharp contrast to the buzzy features and documentaries that get picked up after their premieres at Cannes, Sundance, and the like. Instead, experimental documentary festivals are highly insular and self-sustaining. For example, museum curators and other festival programmers will attend festivals to scope out new work, replenishing the ecosystem when their own festivals or series occur.

For many of us (and I count myself among those who, since entering this world, haven’t left it), it begins with personal connections, often through college instructors who themselves regularly travel the festival circuit.{4} Students might attend a festival because they worked on a professor’s film, or they might have submitted to a festival on the encouragement of their mentors. For a young person especially, it can be thrilling to discover a large and thriving community of like-minded film enthusiasts. My path to criticism was similar. I started going to film festivals after studying avant-garde film in college and interning at a museum and an experimental film distribution company. These experiences, in turn, shaped how I approached festivals. When I first began attending festivals in 2001, I was excited by the prospect of seeing so many films and also daunted by the task of selecting which ones to watch. With no industry contacts and no real connections, I scanned the program for the familiar and found it in experimental work: a series of Ken Jacobs’s work at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, a Robert Beavers program at Views from the Avant-Garde, a guest-programmed screening by Jean-Marie Téno at the Images Festival. I had only known these filmmakers through a classroom setting, and outside of that protected space I was surprised and delighted to learn that they mattered in the “real world” too. It was thrilling to encounter filmmakers whose work I had seen in my classes, and, after mustering a bit of courage, to chat with them after a post-screening Q&A.

Within these avant-garde film spaces, I began to encounter a newer form of experimental-friendly documentary. Like avant-garde film, these films frequently employed elliptical structures, an attention to surface effects and framing, deliberate temporal manipulation (especially as it contributes to a sense of slowness), and small-scale modes of production. Meanwhile, these works were also rooted in the specificities of a situation, issue, or historical event. This is to say not that avant-garde films eschew documentary concerns, but that the experimental documentaries I started to see at this time prioritized what Okwui Enwezor described as “art’s engagement with social life,” no matter how oblique their treatment.{5} Some examples:

the films produced through the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab, like Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel’s LEVIATHAN (2012), which includes the defamiliarizing view of GoPro cameras on a North Atlantic commercial fishing vessel;

the films produced through the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab, like Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel’s LEVIATHAN (2012), which includes the defamiliarizing view of GoPro cameras on a North Atlantic commercial fishing vessel;

blended docufictions like Mati Diop’s MILLE SOLEILS (2013)

blended docufictions like Mati Diop’s MILLE SOLEILS (2013)

or Ben Rivers and Ben Russell’s A SPELL TO WARD OFF THE DARKNESS (2013);

or Ben Rivers and Ben Russell’s A SPELL TO WARD OFF THE DARKNESS (2013);

and essayistic or observational investigations of history and place, like Nicolás Pereda’s EL PALACIO (2013),

and essayistic or observational investigations of history and place, like Nicolás Pereda’s EL PALACIO (2013),

Kevin Jerome Everson’s PARK LANES (2015),

Kevin Jerome Everson’s PARK LANES (2015),

and Zack and Adam Khalil’s INAATE/SE/ [IT SHINES A CERTAIN WAY.TO A CERTAIN PLACE./IT FLIES.FALLS./] (2016).

and Zack and Adam Khalil’s INAATE/SE/ [IT SHINES A CERTAIN WAY.TO A CERTAIN PLACE./IT FLIES.FALLS./] (2016).

Important antecedents to this work include James Benning’s structural landscape films (involving considerable fabrication behind what appears to be unaltered documentary footage), which began to circulate widely in European television and art spaces in the mid-90s; Agnès Varda’s celebrated The Gleaners and I (2000), which blended the forms of diary, social-issue documentary, and essayistic rumination to widespread acclaim; and a 2010s interest in essay films, from Jean-Pierre Gorin’s traveling program, launched at the Austrian Film Museum in 2007, to Timothy Corrigan’s book on the subject in 2011.

The documentary emphasis of experimental documentary—namely, works that address real, often exigent situations—revives a key debate of the historical avant-garde film. Famously, Annette Michelson argued in 1966 that film’s inherent revolutionary potential could best be glimpsed when its formal and political aspects were unified, as in the Soviet cinema of the 1920s and 30s, in the work of Godard and other French New Wave directors, and in the American avant-garde. The radical aspiration of these moments was imperfect and short-lived, however, dissipated by co-option by the state and absorption into industrial cinema. Even in the case of New American Cinema, whose cooperative distribution structure preserved some degree of economic, if not political, autonomy, Michelson was still cautious. About the films of Stan Brakhage and Jonas Mekas, she warned, “the formal integrity that safeguards that radicalism must, and does, ultimately dissolve.”{6} In her formulation, form cannot exist in a void. A film is always an entry into a set of sociopolitical conditions. Hence there can be no guarantee, no fixed form of radicality. The radicality of a film lies in its aspiration, which is a gesture toward a “sense of the future”: the revolution it awaits and also makes possible.{7} Paradoxically, then, a radical aspiration aims toward what remains unfixed, even as it can only accrue meaning in situ. The film itself is the means of changing the possibility of the future.

Much has changed since the time of Michelson’s writing. The horizon of revolution has shifted: it is more discrete, concrete, and aligned with activist efforts, and it occurs both inside and outside the world of art. Doubtless the struggle continues, but no longer is there a sense of a unified film front, a manifesto-scribbling cinema culture leading the anti-capitalist charge. While experimental documentary inherits the mantle of formal-political radicalism, most films of this type do not express an overt, pointed politics, such as one would find in the case of Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Hito Steyerl, or Harun Farocki (and it may be telling that most examples of this type of overtly political work are made outside of North America, in an art-world context). More frequently, a film’s engagement with the real occurs alongside lyricism, extended observation, and sensorial immersion. Salomé Jashi’s Taming the Garden (2021) offers a case in point. The film, which depicts the uprooting of centuries-old trees and their relocation to a billionaire ex–prime minister’s island, embeds its critique within long and otherworldly mises-en-scène. It is ambiguous whether this blunts or sharpens the film’s politics. Is the film attuning to politics in a different register—and thereby advocating for this cordoned-off form of political critique—or is it overwhelming it with nonverbal information? A case could be made for any and all of these possibilities. A similar issue arises with Sensory Ethnography Lab films, where the privileging of sensorial detail over spoken language can be seen as either phenomenological enhancement or evasion of expression. Some of this can be understood as a response to mainstream documentary’s emphasis on moral and political emergency, or what Pooja Rangan has productively described as “immediations,” where documentaries serve as tools of a neoliberal, humanitarian (interventionist) agenda.{8} A more ambiguous, observational nonfiction film may be less useful to such a cause, and thereby more resistant to co-optation. I do not mean to qualify the value of politics in documentary, nor to suggest a right way to do it. Rather, my point is descriptive: Given its roots in the overt politics of Michelson’s era, experimental documentary has drifted to something more obscure. The configuration of this moment tends to locate experimental documentary’s relationship to political movements in the backseat.

Excerpt from TAMING THE GARDEN (Salomé Jashi, 2021).

Experimental documentary generally takes aim at politics out there, but it is rarely directed inward, toward the institutions that support and sustain it. Unlike the historical avant-gardes of the early twentieth century, which attacked the bourgeois institutions from which they sprang, there are exceedingly few instances where an experimental documentary has critiqued film festivals, museum showcases, streaming platforms, test screenings, film schools, grant applications, artist residencies, or anything pertaining to the social existence of a film. (The exceptions that exist come from filmmakers that tend not to show in these spaces, being either too experimental or too documentary: Owen Land’s satirical Undesirables, 1999, is a portrayal of New American Cinema as imagined by Hollywood; Caveh Zahedi’s The Sheik and I, 2012, features the filmmaker confronting the taboo topics that shape the condition of his participation in the Sharjah Biennial; and Claire Simon’s more straightforward documentary The Competition, 2016, examines the entry process at the famously grueling French film school La Fémis.) Perhaps because, in experimental documentary, there is already an assumed oppositional stance toward mainstream film and documentary, there is a corresponding, though less explicit, protectionism toward the institutions of avant-garde film itself. Still, we should remember that even the most ramshackle, labor-of-love screening series is an institution, and as such it is subject to demands that may differ from those of the works it exhibits. Sun reminds us that institutions strive for permanence, and often the stability they seek is gained by regularly showing oppositional, “edgy” work. That is to say, subversive work often cooperates quite well with the preservative interests of the institution.

Just as formal integrity is no safeguard for radicalism, the reverse is also true, that radicalism is possible even under circumstances of formal impurity.

Currently, the festival structure materially sustains the vast majority of experimental documentary films being made. Experimental documentary film festivals serve both as exhibition venues and as engines for marketing, though they sometimes provide direct material support for filmmakers through prizes and production funding. While avant-garde filmmakers of previous generations would likely reject this level of institutional entanglement, contemporary makers have found ways to thrive within it. The festival is itself a manifestation of form, an enlarged social sphere that contains and makes possible certain types of work. If we consider the festival as a formal determinant, we might hear Michelson’s words differently. Just as formal integrity is no safeguard for radicalism, the reverse is also true, that radicalism is possible even under circumstances of formal impurity.

This kind of festival infrastructure has been supported by three major factors: a new interest in documentary form in the art world, the contraction of state funding for experimental work, and the expansion of public funding in Europe for film productions and festivals. First, there has been an increase in supply, largely supported by the supposed documentary turn in contemporary art (or what may well have been the result of the European influx of funding). Much of this began as moving image–based, and typically digital video, installation, and it was largely made by younger artists. Among an earlier generation of artists, many began as filmmakers, including Isaac Julien, Joan Jonas, Hito Steyerl, and Harun Farocki, while others maintained a documentary sensibility from the start. Mark Nash and Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta 11, in 2002, marks a watershed moment when documentary aesthetics in moving image form became a dominant mode of artistic practice. Following that event, artists began to seek out spaces beyond galleries and museums to exhibit their work. Many, like the Otolith Group, converted works from gallery formats to single-screen versions for the theater (or vice versa, as in the case of Morgan Fisher); or, like Garrett Bradley, Dani and Sheilah ReStack, Laure Prouvost, Ben Rivers, Ana Vaz, Sky Hopinka, Luke Fowler, and Leslie Thornton (the list could include almost every experimental filmmaker working today), and, among an older generation, James Benning, Jonas Mekas, and Phil Solomon, began making works alternately for both gallery and theater spaces.

Second, funding for experimental work has diminished, especially, in the US, at the state and federal levels. The “culture wars” of the 1980s and 90s led to significant cuts to NEA funding. At the state level, too, there was a substantial decline. For example, B. Ruby Rich, who directed the film and video programs at NYSCA from 1981 to 1991, recalls budget cuts for films as well as staffing cuts made by Mario Cuomo, then governor of New York. Meanwhile, competition among filmmakers has increased. While in the 1970s more funding was devoted specifically to experimental film, the 1980s saw demand from independent, feminist, and Black artists, as well as various groups experimenting with video and public access television. Rich explains: “The funding had to be spread across many different sectors of the state’s film world—which the experimental folks saw as a ‘betrayal’ often.”{9}

The major awards that remain today come from private foundations, as in the case of the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Herb Alpert Award, and the LEF Foundation Moving Image Fund. Even then, the size of the grant has diminished. For example, in 1978 and 1979, the first years in which the Jerome Foundation (est. 1964, originally as the Avon Foundation) began regularly funding experimental film, awards hovered around $10,000 and favored avant-garde filmmakers and artists: Marjorie Keller received $10,000 in 1978; Robert Gardner, $10,000 (1978); Lizzie Borden, $15,000 (1978); Ken Kobland, $10,450 (1979); John Knecht, $11,000 (1979); Martha Haslanger, $9,000 (1979); and Bette Gordon, $10,000 (1979). Meanwhile, the twelve awards given by the Jerome Foundation in 2019 were, with one exception, $30,000 grants (worth roughly $8,000 in 1979), and, similar to the situation in NYSCA funding in the 1980s, these grants covered a broad range of genres, including “animation, documentary, experimental or narrative genres, or . . . any combination of these forms.”{10} While it is difficult to determine what counts as experimental versus experimental documentary, it is perhaps notable that there is only one project among the 2019 award recipients that uses the word experimental in its description (Mónica Savirón’s The Ledger Line).

Third, a rise in state funding in Europe has supported increased production as well as festival spaces. This is owing in part to the formation of the European Union and a conscious effort to support a sense of economic as well as cultural integration and collectivity. Film festivals offered an opportunity to fund national projects as well as assert regional hegemony. Notably, this is a phenomenon that takes place largely in Europe, with European festivals and European filmmakers and artists, and there is significant overlap and interaction with the US context, which has historically provided a strong base for experimental work. Important exceptions to the European-US context include Festival International de Cine de Valdivia, Chile (est. 1993); the Expanded Cinema section of the Jeonju International Film Festival (est. 2000); Encuentros del Otro Cine EDOC, Ecuador (est. 2002); Experimenta India (est. 2003); and Ambulante (est. 2005).

To varying degrees, existing festivals adapted to accommodate these works, making room for experimental film, digital video, longer-form films, and hybrid approaches to nonfiction. These include festivals whose entire focus shifted, like the Locarno Film Festival (est. 1946), the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen (est. 1954), the Flaherty Seminar (est. 1954), the Ann Arbor Film Festival (est. 1963), International Film Festival Rotterdam (est. 1972), FIDMarseille (est. 1989, with Jean-Pierre Rehm becoming director in 2002), Cinéma du Réel (est. 1978), and Onion City Experimental Film + Video Festival (est. 1980s and run by Chicago Filmmakers starting in 2001). They also include sidebars created to accommodate such work at more mainstream festivals, including the Paradocs (est. 2004) section at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (est. 1988), and the addition of Views from the Avant-Garde (1997–2013) to the New York Film Festival (est. 1963).

It can be useful to track the development of festival spaces through the career trajectory of individual filmmakers. This is not to conflate the institutional space with the form and stakes of the work in question, but to examine how each has been responsive to the other in terms of aesthetic possibility. Take, for example, the work of Deborah Stratman, whose films sit at the intersection of experimental, observational, and essayistic practice. She began exhibiting her work in 1990, and soon after began regular festival appearances. Her 2002 film In Order Not To Be Here is the first I’ve found to have been called an experimental documentary, and in 2002 and 2003 it traveled to over seventy screening spaces, including festivals like Sundance, Visions du Réel (est. 1969), and PDX Fest (2001–9), as well as predominantly experimental film spaces, including the Ann Arbor Film Festival, Media City Film Festival (est. 1994), the New York Underground Film Festival (1994–2008), Pleasure Dome (est. 1989), and Conversations at the Edge.{11} The many awards it won were in best experimental film categories. Later in the decade her work appeared more regularly in documentary venues. O’er the Land (2009), an examination of the secular rituals of American life, went to Sundance, Full Frame Documentary Festival (est. 1998), PDX Fest, Courtisane Festival (est. 2002), True/False Film Fest (est. 2004), and CPH:DOX (est. 2003). It won the Ken Burns Award for Best of Festival at Ann Arbor, and Best Documentary Feature at L’Alternativa, Barcelona Independent Film Festival (est. 1993). Stratman’s The Illinois Parables (2016) likewise picked up awards in both experimental and documentary categories.

Excerpt from IN ORDER NOT TO BE HERE (Deborah Stratman, 2002). Courtesy of the artist.

Stratman herself has been explicit about her interest in extending beyond the concerns of experimental film. Her consistent interest in history, whether woven into vernacular practices or inscribed in the language of film, maintains a view that departs from the inwardness of traditional avant-garde film. In a 2018 interview, she distinguished her approach from what Tom Gunning called “minor cinema” filmmakers of the late 1980s and early 1990s: “Their works have an inner politics. But from early on I wanted more of the accidental outside. More of the street. Some socio-political to aerate the work.” A film like The Illinois Parables exemplifies her developing commitment to a history “without words.” In the film’s eleven vignettes, Stratman traverses the historiographical terrain of the state, including the violent expulsion of Indigenous peoples, the utopian experiment of a community of French Icarians, and the murder of Fred Hampton. She visits gravesites, mounds, living rooms, and forests, all the while watching, measuring, and listening for “something ineffable, a force of another dimension, call it God, or sorrow, or awareness, or the burden of the past.”{12} Similarly, it may be possible to observe in this film the invisible presence of the experimental documentary festival, the subtle pressure exerted by the social milieu in which films are made and shared. Stratman’s method indicates the often indirect ways these traces might be detected, beyond the directness of words and other representational strategies.

Words, in fact, can obscure as much as they elucidate. Scholarly and critical writing on experimental work tends to privilege textual features, no matter how engaged with social life a film might be. Stan Brakhage, for instance, called himself a documentarian (of the “inner eye”), and despite his towering stature within the avant-garde, he is most often discussed in terms of his formal practice of hand-painted film and poetic allusion. (The word documentary only arises in relation to Brakhage’s Pittsburgh Trilogy, as if the domain of documentary could be crudely demarcated by the use of a camera in an institutional setting.) The impulse to taxonomize, to make clear-cut distinctions between aesthetic and political concerns, leads to overvaluation of textual analysis and undervaluation of the conditions of production, and the treatment of these two areas as distinct.

This tendency can be seen in various attempts to identify previous moments of overlap between avant-garde and documentary film. In Avant-Doc: Intersections of Documentary and Avant-Garde Cinema (2014), Scott MacDonald selects strains of lyricism within ostensibly nonfiction work, including the city symphonies of the 1920s; the films of Robert Flaherty, Stan Brakhage, and Peter Kubelka; diary films; found footage works; and other instances of formal convergence. Though MacDonald would seem to be offering a corrective to the type of pigeonholing I just described, his emphasis on form ends up reifying the categories he challenges. Absent a serious engagement with the political and historical circumstances of how and why these categories came about, both documentary and avant-garde film become reduced to a set of signifiers. The result is a circuitous taxonomy where the entirety of avant-garde film starts to look like a subset of documentary, or, conversely, documentary a subset of the avant-garde.

MacDonald’s description can be understood as symptomatic of a situation in which exhibition spaces for avant-garde film were largely pivoting either to experimental documentary or to moving image art.{13} Take, for example, the mid-2010s restructuring at Film at Lincoln Center: the experimental documentary series Art of the Real began in 2013, and Views from the Avant-Garde, which for many was the premier destination for American experimental film, was replaced in 2014 by the gallery-friendly Projections program and rebranded as Currents in 2020. Though there was overall an increase in the amount of screen time given to films that fall under the broad umbrella of the experimental, there was less room for abstract, hand-processed, animated, and lyrical work associated with the traditional avant-garde. In many ways, MacDonald’s crossover approach and others like it provided these new festival spaces with a language for describing the innovative, genre-busting works they showcased. These films may also be said to be expensive, in that most are supported by grants or other subsidized sources of support. As Josh Guilford observes, “The prioritization of work with socially and politically relevant content within such exhibition contexts has been co-extensive with a valorization of technical and aesthetic polish. It’s another of the many paradoxes animating this culture.”{14}

What we typically call form does not sufficiently account for the specificities of experimental documentary.

MacDonald rightly identifies the role of the academy, where canons are formed and deepened in courses organized according to genres, methods, national cinemas, auteurs, and the like. Canonic revisions along the lines of avant-doc ultimately reinforce this discursive framing. The role of writing at and about the film festival is equally significant for shaping the types of films deemed acceptable, laudable, or forgettable. At a traditional festival, criticism tends toward best-of-the-fest capsule reviews, seeking to identify trends, breakout talents, and new waves. Though festival reports might devote a few sentences at the beginning and end to describing the flavor of the festival-going experience, they generally avoid delving too deeply into a more ethnographic sketch.

Criticism at the experimental documentary festival inherits and exacerbates these tendencies, as well as their problems. I know of no mainstream critics—that is, critics employed by a major newspaper—who are regularly assigned to cover such festivals. Those that attend and write generally do so on their own initiative, as when Amy Taubin or Manohla Dargis has stepped in to write about Projections for the New York Times. It is important to note, too, that the vast majority of film critics today are freelance, working by pitch at one or more publications, rather than writing exclusively for a single outlet as a staff writer. Furthermore, freelance film critics almost always need to work some other kind of job to earn a living wage. Festivals, even when press credentials are handed out, are expensive to attend. For filmmakers, of course, (formal) participation must be conferred by the festival itself, and even then filmmakers often must pay their own way there. Programmers and other industry professionals must have access to funding to travel. Critics, meanwhile, enter festivals through either application or invitation. The latter usually comes with some incentive, often in the form of hotel accommodations. There is an unspoken assumption that critics will favorably review the festival in return for these perks, and even if a critic is outwardly unbound by these obligations (because the critic may be protected by the reputation of their publication, for instance), they might still feel a sense of constraint. Further complicating matters are the multiple ways a critic might be pulled into festival operations. On a few occasions I’ve been asked to speak on festival panels, moderate director Q&As, or introduce screenings, all while still ostensibly on assignment for a publication.

Given the significant personal investment required, it is unsurprising that there are few critics who cover experimental documentary. Those who do select what they write about tend to isolate individual films to discuss, often tracking a thematic throughline across festival offerings. There is also little incentive to write disparagingly about any film. In my own criticism, I have been acutely aware that my writing might be the only press a film will ever receive, and that it is often used for program notes, catalog text, and grant applications. The festival community exerts its own social pressure as well. It is often easier to simply avoid writing about a film than to take issue with it in writing, and the result is that the criticism is skewed toward an abundance of praise with a narrowing of selection. Surely, too, are programmers aware of the influence they exert. The shared perception of experimental documentary’s fragility, of its scarcity and vulnerability, invariably shapes the value system of the festival. This skews the public understanding of the festival, and also misrepresents it to its own community, which ends up reproducing the same distortion. Undoubtedly, more and more diversified criticism, including negative takes but also writing that does not adopt an evaluative framework, is needed. We should recognize, however, that publication venues operate on their own financial models, and that, for better and for worse, they are not beneficiaries of the sources that fund experimental documentary films and festivals.

One unusual result of these pressures is that critics have sought out other ways of participating in film culture. This is also a historical phenomenon, where a number of critics that were writing in the late 1990s and early 2000s shifted to programming, including Rachael Rakes, Dennis Lim, Ed Halter, Jean-Pierre Rehm, Federico Windhausen, and Mark Peranson. Where in the 1960s the critics of Cahiers du Cinéma became directors, the experimental documentary space of the 2000s was largely shaped by critics turned programmers. This coincides with the enlarged role of the programmer more generally at film festivals, cinematheques, and other exhibition venues, and it should be noted that a number of filmmakers, like Sylvia Schedelbauer, Ben Russell, and Ben Rivers, were also active programmers during this time. The critic’s sensibility in programming is perhaps evident in the strong thematic cohesiveness of programs organized by these critics- and filmmakers-cum-programmers. For instance, Rakes and Lim’s Art of the Real is recognizable for its essayistic, intellectual, and political character, while Windhausen’s Pueblo program at the 2016 International Short Film Festival Oberhausen assembled films reflecting the historical and contemporary possibilities of collectivity in Latin America. Such programming departs from mainstream festival programming—which emphasizes heterogeneity and variety—and in its narrower focus is closer to a curatorial model of selection. Hence the critic’s turn to programming, or programming in a critical vein, motivates much of the coherence of experimental documentary as a formal category with institutional endurance.

Video: THE OTHER SIDE (Roberto Minervini, 2015). Audio: Minervini in conversation with Dennis Lim following a screening of THE OTHER SIDE at the 2016 edition of Film at Lincoln Center’s Art of the Real, programmed by Lim and Rachael Rakes.

What we typically call form—namely, the aesthetic characteristics of an artwork—does not sufficiently account for the specificities of experimental documentary. It’s time to enlarge the notion of form beyond the text, to the social world in which it is made and received. MacDonald’s point about predecessors for experimental documentary is an important one, and we might look to earlier examples of radical film form and the institutional supports that sustained them to better understand the contours of the present. How do Cinema 16 and other early incubators of avant-garde film differ from the festival spaces that dominate the contemporary landscape? To address these important concerns, one would need additionally to unpack the historiographical record where discussions of form have prevailed at the expense of institutional analysis. Though they are beyond the scope of this essay, I hope that these reflections might prompt a more integrated understanding of the relationship between aesthetics, politics, and institutional formation in the many histories of experimental moving image work.

Festival infrastructures are as important as aesthetic markers in determining what counts as experimental documentary. One cannot fully comprehend experimental documentary outside of the festival ecosystem in which it is made, programmed, viewed, and written about. It is precisely this outside that has been largely excluded from most writing on avant-garde and experimental documentary film. I hope that both critics and scholars can find new ways to invite texts and contexts into dialogue. Or, as Stratman reminds us, both in her films and in her own words, to remain “attentive to the accidental outside.”

Acknowledgments: I thank Walter Argueta-Ramirez, Erika Balsom, Colin Beckett, Chris Cagle, Jason Fox, Leo Goldsmith, Josh Guilford, Pacho Velez, and Chi-hui Yang for helping me think through the many vectors of experimental documentary film festivals.

Title Video: In Order Not to Be Here (Deborah Stratman, 2002).

{1} Among the preexisting festivals that shifted emphasis to experimental documentary or supported experimental documentary sidebars were the Locarno Film Festival, the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, the Berlin International Film Festival (est. 1951, with Forum Expanded beginning in 2006), the Flaherty Seminar, the Ann Arbor Film Festival, International Film Festival Rotterdam, International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, FIDMarseille, Cinéma du Réel, Onion City Experimental Film + Video Festival, and Views from the Avant-Garde.

{2} Festivals founded in the 1990s include Hot Docs (est. 1993), Sheffield DocFest (est. 1994), and the Montreal International Documentary Film Festival (RIDM) (est. 1998). In the 2000s: Doc’s Kingdom (est. 2000), Courtisane Festival, Doclisboa (est. 2002), Punto de Vista International Documentary Film Festival of Navarra (est. 2005), Ambulante, and Play-Doc (est. 2005). In the 2010s and after: Open City Documentary Festival (est. 2011), Mimesis Documentary Festival (est. 2020), and Prismatic Ground (est. 2021).

{3} Abby Sun, “Giving Time: Amos Vogel and the Legacy of Cinema 16,” Film Comment Letter, November 15, 2021.

{4} The academy is also an important institutional support for the production, circulation, and cultural prestige of experimental documentary. As an extension of the relationship between avant-garde filmmakers and the academy, colleges and universities are often where filmmakers maintain “day jobs,” which may involve funding for research and creative practice, compensation for speaking and screening engagements, and royalties from library acquisitions of DVDs and streaming rights to films. Further, the academy, in the form of scholarship and teaching, grants cultural legitimacy in elevating experimental documentary to the status of critical, engaged, and political media forms, which then reinforces its raison d’être.

{5} Okwui Enwezor, “Documentary/Vérité: Bio-Politics, Human Rights, and the Figure of ‘Truth’ in Contemporary Art,” in The Greenroom: Reconsidering the Documentary and Contemporary Art #1, ed. Maria Lind and Hito Steyerl (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2008), 64.

{6} Annette Michelson, “Film and the Radical Aspiration,” in Film Culture Reader, ed. P. Adams Sitney (New York: Cooper Square Press, 2000), 416.

{7} Ibid., 421.

{8} Pooja Rangan, Immediations: The Humanitarian Impulse in Documentary (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).

{9} B. Ruby Rich, email to author, November 23, 2021.

{10} “New York City Film, Video and Digital Production Grant,” Jerome Foundation, accessed February 15, 2022.

{11} Kelly Vance, “Critic’s Choice: Deborah Stratman’s In Order Not To Be Here,” East Bay Express, May 7–13, 2002.

{12} Deborah Stratman in Jason Fox, “‘Where Are Those Lines?’: Discussions About and Around Experimental Ethnography with Sky Hopinka, Naeem Mohaiemen and Deborah Stratman,” in A Companion to Experimental Film, ed. Federico Windhausen (New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 2022).

{13} David E. James offers an opposite and more historically grounded account of the intersection of documentary and the avant-garde. In his formulation, avant-garde film and a politically engaged, militant form of documentary emerged from the underground cinemas of the 1950s and 1960s. Shifting social and political realities upset the “balance between the aesthetic and the existential that allowed the making of art to be both self-validating and the central ritual in a countercultural revolt.” From there arose the protest films of the various Newsreel chapters and related projects like Saul Levine’s film New Left Note (1968–82). Jonas Mekas, one of the key organizers of the New American Cinema movement, drew a direct line between these two areas of filmmaking activity, declaring that there was “no difference between the avant-garde film and the avant-garde newsreel.” From James’s perspective, the avant-garde was in its earliest formations involved in political agitation, in large part due to its social organization in small communities. It only later broke away into purely formal concerns. David E. James, Allegories of Cinema: American Film in the Sixties (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 164; Jonas Mekas quoted in ibid., 167.

{14} Josh Guilford, email to author, December 16, 2021.