Telling Something Else: Documentary Beyond (Hi)story

Alex Johnston

How do we tell a story, when there is no story to tell?

This is a digital photograph of the screen of a microfilm reader, showing an image from a newspaper article published in a Galveston, Texas newspaper, circa 1913:

Figure 1. Photograph of microfilm. A SURVIVOR. Photograph by the author (2015).

Figure 1. Photograph of microfilm. A SURVIVOR. Photograph by the author (2015).

The image depicts a young African American man.{1} When the original photograph was taken, the man was incarcerated at the Harlem Prison Farm, a state-owned plantation located in East Texas, just outside Sugar Land. I came across this image in the Galveston Public Library in the spring of 2015, while conducting research about an incident that took place at the Harlem Farm in 1913.{2} Here is the photograph again, now zoomed in on the man’s face:

Figure 2. Photograph of microfilm. A SURVIVOR (CLOSE-UP). Photograph by the author (2015).

Figure 2. Photograph of microfilm. A SURVIVOR (CLOSE-UP). Photograph by the author (2015).

While the plastic screen of the microfilm reader was a little cloudy with age, and my hand a little shaky with the weight of the camera, the lack of detail in the man’s features predates these circumstances of transmission. The dissolving of eyes, nose, mouth, and chin into a vague agglomeration of sepia tones perhaps occurred during the transformation from emulsion to ink, from ink back to emulsion, or from some combination of the two processes. Regardless of the cause, the outcome is historical erasure.

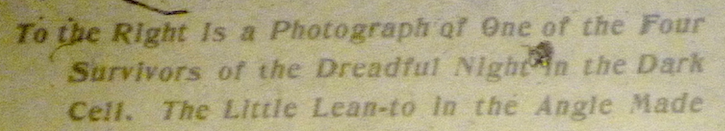

Now, here is the newspaper caption that accompanies this image:

Figure 3. Photograph of microfilm. A SURVIVOR (CAPTION). Photograph by the author (2015).

Figure 3. Photograph of microfilm. A SURVIVOR (CAPTION). Photograph by the author (2015).

The caption is foreboding and intriguing, referencing a “dreadful” incident which this man survived, indicating that others did not. It also contains a notable absence. It doesn’t tell us the man’s name. We are told he is one of “four survivors,” but which one? The article does not give us this information, but it does tell us the names of the four survivors: Edgar Evans, John Douglas Burrell, James Curtis, and Ollie Brown. The man in the photograph is one of these men. The lack of identification compounds the act of erasure.

Between this article, other contemporary news sources, and institutional documents and reports, we can piece together the basic facts surrounding the “Dreadful Night in the Dark Cell.”

On the afternoon of September 6, 1913, twelve African American men at the Harlem Prison Farm were forced into a small wooden box (9 x 7 x 7 ft, with four auger holes in the ceiling and four one-inch pipes in the floor for ventilation), as punishment for their role in a cotton strike. They were protesting work conditions in the prison, withholding their labor through coordinated slowdowns and stoppages. According to contemporary news accounts, the temperature that day reached 100 degrees.

Once inside the dark cell, the prisoners pleaded to guards that there was not adequate ventilation. Their pleas were ignored. Said one of the guards: “sometimes when there is a bunch in there, they will make out they’re suffering.”{3} The men were left in the dark cell for the rest of the day and through the night. When the guards went to release the prisoners the following day, they discovered that eight of the men had died, asphyxiated by foul air. The “four survivors crouched in each corner, their mouths wrapped around the floor pipes, gasping for air.”{4} The killing of the eight prisoners received some national news coverage, but the incident’s presence in the media rapidly subsided with the speedy exoneration of the guards responsible.

The death of the eight men occurred at a time when such deaths were common. The incident did not result in changed laws or changed minds. No reforms were instituted in the Texas prison system, and no public outcry kept the deaths in the spotlight.{5} The men did not become martyrs.

The “unremarkable” nature of what happened to the men at the Harlem Prison Farm doomed their deaths to obsolescence. Contemporary indifference by those in power, by those with a voice, persisted across time. It continues into the present day. Two mutually informing dynamics—a scant archival trace and the lack of a cohering narrative—have rendered the incident a footnote in histories of carcerality and race in America.

In his book The Content of the Form, Hayden White theorizes that what differentiates a work of history from a basic chronological recording of past events (such as in the chronicle and annal forms) is the use of narrative to produce meaning and closure. The imposition of these structuring elements, he argues, allows us to orient historical events “with respect to one another and . . . charge them with ethical or moral significance.”{6} While the narrativization of the past produces meaning-as-history, the palimpsest of the past requires that such a project diminishes and excludes the vast majority of events and people, regardless of ideology. As a “typical” event in the history of the Jim Crow South—the brutalization and murder of poor black men—the incident at Harlem Farm has evidentiary value to historians of the left, but no easily discernible narrative value. It offers no closure in the way of fomenting cultural or legislative change, and its tragic moral and ethical significance is not perceptibly different from myriad other incidents of the period.

The lack of clear images and the lack of a historical narrative has also made the event unsuitable for representation in the domain of contemporary mainstream documentary practices. No images + no story = no film. And in this case, all we are left with are a few newspaper articles, some internal memos and telegrams about the incident, the names of the prisoners, and a blurry photograph of one of the survivors.

We don’t know which one.

There is no name for what happened there. It is not known as “The Harlem Massacre.” The men are not referred to as “The Harlem Eight.” The story of the incident has never been told in documentary form, in large part because it has never been told in historical form, which is to say, in narrative form.

In this way, a documentary practice based in story, dependent on visual evidence, compelled by narrative historiography, perpetuates social erasure and historical death. White writes that, “Far from being a problem . . . narrative might well be considered a solution to . . . the problem of how to translate knowing into telling.”{7} But what if the lack of a legible narrative framework to convey an event is itself the problem?

How do we documentarians tell a story when historians have determined that there is no story to tell?

Perhaps the best answer is the most obvious one. We don’t. We “tell” something else. For instance, we can honor and memorialize and make those deaths “count” by simply counting them:

Tom Reed, Age 18. Cause of death: suffocation. Place of death: Harlem Prison Farm.

Calvin Jefferson, Age 19. Cause of death: suffocation. Place of death: Harlem Prison Farm.

Will Campbell, Age 18. Cause of death: suffocation. Place of death: Harlem Prison Farm.

Jesse Thompson, Age 18. Cause of death: suffocation. Place of death: Harlem Prison Farm.

Robert Carpenter, Age 17. Cause of death: suffocation. Place of death: Harlem Prison Farm.

Bill Tinner, Age 18. Cause of death: suffocation. Place of death: Harlem Prison Farm.

Miles Berry, Age 18. Cause of death: suffocation. Place of death: Harlem Prison Farm.

Carlton Vance, Age 17. Cause of death: suffocation. Place of death: Harlem Prison Farm.

The counting—or the accounting, or the recounting—does not change the fate of the eight men who died in the box, and it does not give a face (or a name) to the survivor in the photograph. Yet it does make legible their erasure, and in so doing, hopefully compels us to question its causes and reasons. Returning these eight men to the overlapping domains of history and memory, can also make visible the agents and institutions that sought to (and seek to) annihilate them. Where there are victims, there are also, always, victimizers.

The men at Harlem Prison Farm were deprived of a historical narrative of their lives and deaths. But that doesn’t mean they need to be forgotten. As documentarians committed to the urgent work of producing liberatory media about the past, it is incumbent upon us to ensure that they (and others like them) are remembered, regardless of whether there is a story to tell. The work of how we remember, beyond story, beyond history, can only begin when we understand how the opposite has come to pass; how through story, and history, we also forget.

Title Video: A Costly Lesson (Johnston, 2016).

{1} From the “Convict Record of the Texas State Penitentiaries” we can determine the man’s age within a few years. At the time this photograph was taken, he was between 17-19.

{2} That research resulted in the creation of two short films, the upcoming Dark Cell Harlem Farm (2021) and A Costly Lesson (2016). The latter film offers one example of the kind of non-story-driven historical documentary practice that I advocate for in this essay. You can watch it here.

{3} Meigs Frost, “Dark Cell Survivors Tell of Experiences,” The Dallas Morning News, September 9, 1913.

{4} Robert Perkinson, Texas Tough: The Rise of America’s Prison Empire (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2010), 174

{5} In a perverse irony, the dark cell as a mode of punishment was itself a product of a recent cycle of reform. It was implemented as a more “humane” form of punishment throughout the Texas prison system, following the outlawing of the bullwhip and the bat a few years prior.

{6} Hayden White, The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987), 11.

{7} Ibid., 1.