Technological Ecologies of Encounter

Counter Encounters (Laura Huertas Millán, Onyeka Igwe, and Rachael Rakes)

So much blood in my memory! In my memory are lagoons. They are covered with death’s-heads. They are not covered with water lilies.

In my memory are lagoons. No women’s loin-cloths spread out on their shores.

My memory is encircled with blood. My memory has a belt of corpses!

—Aimé Césaire{1}

****

Among its legacies of violence, colonialism instituted a “Stone Age” myth that denied the very existence of such a thing as non-Western technology—that term being reserved for tools and machines of strictly Western manufacture. The narrowness of this concept of the technological has been contested along various fronts. As Enrique Rodríguez-Alegría reminds us, technology is also “the physical and material ways of making and using things (or performing an effective action on nature or others) in their culturally meaningful social, political, and economic contexts. Technology has aspects that are human, material, and immaterial.”{2} In this view, technology includes poetry, such as the work of Césaire above; it can also come from plants, animals, and social relations, always in development and always at the edge of human understanding.

Inspired by sites where nature and culture, the organic and the scientific, the human and the more-than-human merge in ways that threaten to dislodge these binaries altogether, this issue of World Records thinks through the frame of technological ecologies, which analyzes and contests the division between the ecological and the technological in an array of audiovisual practices. This issue integrates cinematic and recording devices into embodied, affective, and political nonfiction creation—resonating with Arturo Escobar’s notion of sentipensar (feel-think), which suggests “a way of knowing that does not separate thinking from feeling, reason from emotion, knowledge from caring.”{3}

Similarly, we approach ecologies as means of cosubjectivity between human and nonhuman beings, paying attention, as Dwayne Donald encourages, “to the webs of relationships that [we] are enmeshed in, depending on where [we] live, . . . all the things that give us life, all the things that we depend on, as well as all the other entities that we relate to.”{4} Ecology is an intrinsic framework of all encounters, one in which bodies and lands communicate and preserve a common memory, as Aimé Césaire’s inscription suggests. But how can cinema—an apparatus embedded in colonialism and a key tool in the imposition of cultural binaries—be used to dismantle colonialism? How can recording technologies help rebuild or preserve relationships and forms of kinship with more-than-humans? Toward that end, the concept of encounter has been pivotal in our research. We are drawn to forms of anti- and alter-ethnographies in cinema and contemporary art that center marginalized histories and historical thinking, and to makers who refuse the fixed identities assigned to them by foreign eyes—by colonizers, anthropologists, artists, tourists, missionaries, politicians—and work to reclaim authorship of images.

Ethnography is both a site of criticism and an inspiration for this issue. We approach the discipline, following Mario Blaser and Marisol de la Cadena, as a “scholarly genre that conceptually weaves together those sites (and sources) called the theoretical and the empirical so that thereafter they cannot be pulled apart.”{5} This means navigating ambivalence. It means often being critical of histories of humanist study without completely cutting ourselves off from those histories. It means honoring the complexity and considering the double binds inherent to each of our diasporic experiences. We commissioned the works in this issue with three overarching themes in mind: cinema as a colonial technology of encounter, and its refusals; other spaces of otherness; and silences, absences, and the activation of traces. The contributors to this issue deal with these complexities in different measures from different and unequal social, cultural, political, and geographical locations.

****

Cinema as a colonial technology of encounter, and its refusals

“How do we see technology?” asked the archeologist André Leroi-Gourhan. In posing this question, he pointed to the necessity of thinking about the cultural frameworks of ethnological records before using them as a scientific base for studying the history of humankind. If recording technologies are inseparable from the cultural desires and needs that produce them, he asks, then how can we distinguish a “bad document” from a good one? This is why, for Leroi-Gourhan, “technology is destined to constitute a discipline in itself and not only a technical support.”{6} Echoing Leroi-Gourhan, Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison demonstrate how various Western cultural sentiments were embedded in and concealed by technological processes. Mechanized science, they write, “seems at first glance incompatible with moralized science, but in fact the two were closely related. While much is and has been made of those distinctive traits—emotional, intellectual, and moral—that distinguish humans from machines, it was a nineteenth-century commonplace that machines were paragons of certain human virtues.”{7} So which human virtues did the film camera exemplify?

Recording devices were expected to express honesty, courage, and tenacity; they were intended to leave behind any somatic expression of the person using the device, and to assure the delivery of an impartial, true-to-life representation. “As the photograph promised to replace the meddling, weary artist, so the self-recording instrument promised to replace the meddling, weary observer.”{8} And yet, the invention of photographic and cinematic machines repeatedly emulated neither strong morality nor virtue, proving Daston and Galison’s point about the impossibility of machines to be the result of pure idealism. Scopic pleasure was central to the cinematographer’s invention. The zoöpraxiscope, the magic lantern, the Théâtre Optique, and the phenakistiscope, among other inventions, were attempts to decompose, to recreate movement in settings that expanded the perception of the dramaturgical live experience and enhanced the illusion of reality. As were the technologies of weapons (the photo revolver by Jules Janssen and the chronophotographic gun by Étienne-Jules Marey), white settler’s leisure (horse races), and industrialization.{9} The convergence of science, spectacle, war, and whiteness in the invention of the cinematic machine should not be understated, as soon it became an instrument actively involved in colonial processes.

In 1896, a team of filmmakers trained by the Lumière brothers in single-shot filmmaking made expeditions to London, Rome, New York, Frankfurt, Madrid, Moscow, Budapest, Mexico City, Sydney, Algiers, and Saigon, filming, among other subjects, colonies and colonial exhibitions.{10} Analyzing the films of these self-proclaimed chasseurs d’images (image hunters), archival scholar Katherine Groo points to the deterritorializing and exoticizing effects of their moving images: “These films do not overcome ideological strictures but make them visible,” while “transform[ing] the world on-screen into one of seemingly endless geographic permutations.”{11} The Lumière alumni, for all their seemingly naive interest in recording the pastoral life of foreign others (detached from the contingencies of history and time), operated in step with the racist ideologies omnipresent in their West.{12} Photography and the newly invented cinema were inevitably part of these colonial projects, if not the center; cinema was a register of the so-called “civilizing mission” of the West, and it assured this mission a mainstream spectacle.{13}

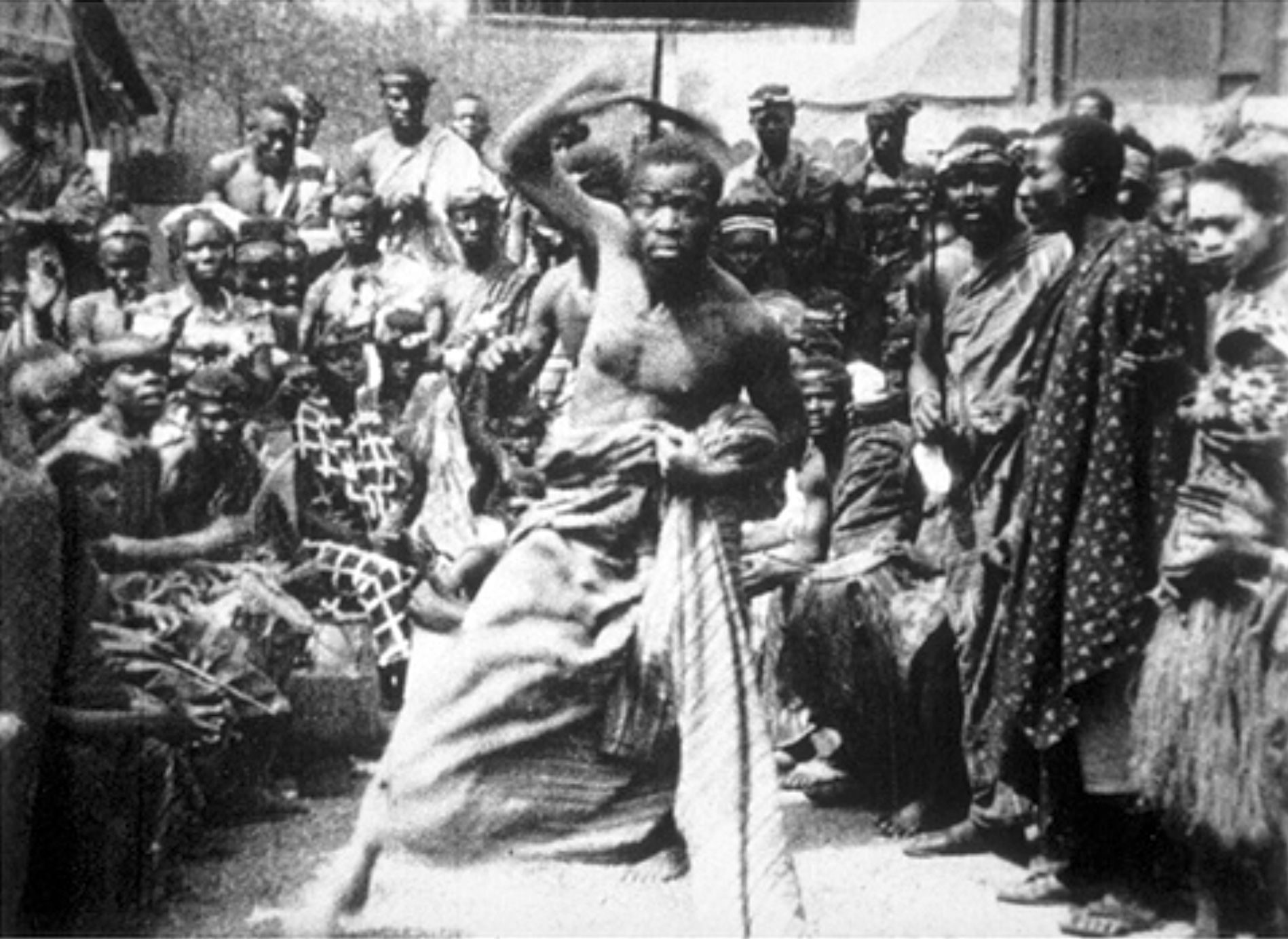

DANSE DU SABRE 1 (unknown operator, 1897, Lyon). Courtesy of Catalog Lumière. “The dancers,” Groo writes, “challenge the camera’s intrusion and disrupt the continuity

of the film; they create ‘cuts’ with their blows, returning the violence of an uninvited witness with the violence of a deftly handled blade.”

DANSE DU SABRE 1 (unknown operator, 1897, Lyon). Courtesy of Catalog Lumière. “The dancers,” Groo writes, “challenge the camera’s intrusion and disrupt the continuity

of the film; they create ‘cuts’ with their blows, returning the violence of an uninvited witness with the violence of a deftly handled blade.”

Groo finds another layer in the Lumière films, however, drawing attention away from the image hunters and toward those being recorded. Examining the films made by Lumière operators in a so-called ethnological exhibition (human zoo) in the Parc de la Tête d’Or, Paris, Groo remarks that these recordings depart from the traditional form of the “attraction film” predominant at the time. Of the film Danse du sabre I (Sword Dance I, 1897) she writes, “The dance is really no dance at all but a set of violent confrontations with the camera, operator, and future spectators. . . . The ‘dances’ contribute yet more sites of conflict and oppositional force.”{14} The camera, as a device of capture that redundantly mimics the visual regime of the zoo (with a single point of view, a rigid face-to-face staging, and a framing meant to abstract and fictionalize the scene, much like a cage does), stumbles upon the real people it films. In spite of their position of double captivity, the people fixed by the camera’s gaze exercise provocation, intimidation, and other embodied signs of resistance. Their agency, the somatic revolt of their return performance, hijacks the images’ ability to subordinate those it captures. Breaches open up within the image—what Groo would call a “subversive force.” Our focus here is on the anticolonial subversive and creative voices that have inherited these colonial histories and the violent foundations of recording technologies (cinema, sound recording, archiving), a violence many of our contributors have to reckon with.

Take as an example Jeannette Muñoz’s film Strata of Natural History (2012), included with her essay of the same title in this issue. Through the use of overlapping exposures, the film evokes the way colonial images haunt diasporic subjectivities. Muñoz repurposes archival photographs taken of Kawéskar people who were forcibly taken from their lands to be featured in nineteenth-century ethnological exhibitions, notably by Carl Hagenbeck and Rudolf Virchow (among other nineteenth-century European zoo entrepreneurs). Interwoven with these images is the filmmaker’s own 16mm footage of urban sites in Germany and Chile that are saturated with colonial history: a zoological garden, the Berlin Ringbahn, and the Fuente Alemana in Santiago de Chile. The associations evoked here—between late nineteenth-century German hunter-explorers and a near-contemporaneous public fountain dedicated to the “friendship” of Germany and Chile—are not to be taken lightly, especially considering both countries’ racialized histories and political dictatorships. But Muñoz touches upon these issues with a radical tangentiality, also present in the written companion to her film, which she is publishing here for the first time.

Excerpt from STRATA OF NATURAL HISTORY (Jeannette Muñoz, 2012). Courtesy of the artist.

Chrystel Oloukoï also takes up questions of national and ethnographic archives, writing about the aftermath of the 2021 University of Cape Town fires that swept through the African Studies Special Collections Library. Throughout “Did the fire read the stories it burnt?,” Oloukoï demonstrates the ways in which Western museological and academic socialization teaches the capture, possession, and ossification of materials in the name of care. Through regimes of classification, the gold-rush mentality of colonial and present-day collections, and ethnographic filmmaking practices, a fetish for the archival reproduces and hegemonizes a regime of truth, cast in the image of Western traditions of encounter. What is it, Oloukoï asks, that we mourn when we grieve the destructive fire of an archive?

“Sovereignties, Activisms, and Audiovisual Spiritualities of the Indigenous Peoples of Colombia” was organized as a virtual roundtable with filmmakers Olowaili Green, David Hernández Palmar, Nelly Kuiru, Mileidy Orozco Domicó, and Amado Villafaña, and moderated by Pablo Mora and Laura Huertas Millán. A multicultural collective conversation about filmmaking from, and for, Indigenous nations in Colombia, the roundtable focuses on questions of audiovisual sovereignty and its relation to the defense of Indigenous cultures and territories.{15} Here, filmmaking becomes a tool to create expressions, stories, forms, and protocols of relationship within and beyond the community, while also offering a site where filmmakers’ own relationships to their cultures, traditions, and ancestral knowledge can unfold within and beyond cinema. Equitable economic distribution, sharing authorship, finding a voice of their own, and struggling against acculturation and assimilation are some of the urgencies that media production allows them to address. “[It’s] about exchanging thoughts and about how we uphold our identity,” says Amado Villafaña.

Transcending the binary between ecology and technology becomes particularly poignant as the roundtable participants describe how the cameras are perceived within their own nations. Amado Villafaña and Pablo Mora evoke, for example, the teachings of the mamo Jacinto (a Kogui spiritual leader), who declares in Colectivo Zhigoneshi’s film Resistencia en la línea negra (Resistance on the Black Line, 2011) that the mother of all images resides in the Arhuacos’ sacred territory. The statement explains why the cameras brought to this territory had to be “baptized” before recording the mamo’s teachings.{16} Baptizing the cameras is a way to reconnect this supposedly foreign technology with its original mother, who lives in Arhuaco territory. The introduction of cameras into the Indigenous world is not, then, an act of appropriation, but rather a logical continuity: there is kinship between the camera and the goddess, therefore the ontology and the essence of the cameras has always belonged to the Arhuacos. Subverting the colonial power structure (the cliché that colonizers brought technologies to Abya Yala), Mamo Jacinto teaches us how the separation between ecology, technology, and spirituality is equally misleading.

****

Other spaces of otherness

Sylvia Wynter conjures the ways that humans have often made meaning of the social world via her concept of “the space of Otherness,” citing examples of monarchy, science, and monotheism. She argues that this space is different at different historical moments and places. It has meant God, kings, gods, spirits, nature, science, and many other things besides.{17} It is the space of nonhuman influence that allows humans to excavate their own agency and permit other beings to be decisive in how social life unfolds. The space of otherness has instruments that explain and enact its logic, names to learn and workflows to adopt. It is epistemology and ontology, a mythos-logos, or technology of sensing the world. Wynter goes further to add that the year 1492 marks a new epoch in which there has been an overrepresentation of the Euro-American-Christian-Western-modernist space of otherness, which has not only marginalized other ways of sensing the world but also sought to end them.{18} This has marked encounter, shaping the terms of the meeting and exchanges of cultures.

Throughout this issue we ask what other technologies it could be possible to use when making film. This question rhymes with one of the ultimate concerns of Wynter’s project: advocating for a capacious approach to the technology of stories—“the cognitive and representational role of storytelling that enables humans to produce and reproduce our social world.”{19} For us, overlooked technologies might point to the multisensorial body, to noncognitive and/or nondiscursive communication, and to technologies of nonhuman and nonliving ways of thinking, being, and knowing.

Given this context, it might appear contradictory to introduce these marginalized forms through the colonial bête noire—the written word—a technology that has reduced and foreclosed alternative spaces of otherness. English-language writing, in particular, continues to dominate the globe. Spivak would call our predicament one of being “inside the enemy,” forced to elucidate alternatives through the very tools that have dominated and erased these alternatives.{20} We must also contend with the incongruity of the written form—how to write about intense sensations that instinctually direct action: the feeling of levity, the tightness of the chest, the deep reverberations of the diaphragm activated by sound, the sweetness of heat, the astringency of air, the irrepressible movement in one’s toes after a memory-triggering scent. Words fail, but but but . . . but how else can we let others know, others who don’t speak the language of our gestures, who don’t know the meaning of St. John’s wort hung on the door frame, who can’t read the tail of a hummingbird, who are not able to communicate with ghosts? At the end of this road, of this search, lies a common tongue, a desire for collective consciousness.

Translation is one path to consciousness. Take, for example, the roundtable of Indigenous filmmakers, which is presented here in both its original Spanish language—it too a colonial language of domination and erasure—and English, which means that all three of us came to the text with varying levels of comprehension. Other contributions to this issue are written in a second or third tongue. Some words are left untranslated, some are untranslatable, and some will inevitably be overlooked and meanings elided in the search for a common place where we might all convene. Perhaps this search, or the desire for the destination, is most acutely felt by those of us who live in between, whose experience of society and culture is plural, whether by dint of birth, economic circumstance, persistent catastrophe, or curiosity, or from a sudden involuntary propulsion. All these possibilities exceed the term diaspora, but this remains the colloquial term for the experience of having multiple centers, multiple spaces of otherness, and multiple technologies with which to communicate. We edited this issue from Amsterdam, London, Paris, and the varying pit stops of work and leisure in between, meanwhile always towing Colombia, Nigeria, and the United States with us. The contributors in many cases also have their own complex positions which reflect the various points of entry and biases that we serve and that serve us.

Animistic Apparatus: Itinerant projectionist troupe Thanawat Phappayon installing the screen at Baan Nong Na Kham Temple, Udon Thani, Thailand, April 2019. Image by Thanatchai Bandasak.

Animistic Apparatus: Itinerant projectionist troupe Thanawat Phappayon installing the screen at Baan Nong Na Kham Temple, Udon Thani, Thailand, April 2019. Image by Thanatchai Bandasak.

One such contributor is the research and curatorial group Animistic Apparatus, who engage and exhibit media and technology through histories and rituals of audiovisual presentation in the Global South. Beginning with Southeast Asian cultures and practices of animism and spirituality, the group has since broadened to find connections between multiple forms of cinematic civic, spiritual, and ecological engagement. Leading from the “animistic” and from contemporary anthropological positions on coexistent ontologies, they explore creative exhibition practices that express relations with human, nonhuman, and ancestral beings. Their omnibus text, “A Gathering,” engages several of Animistic Apparatus’s interlocutors and contributors in a series of observations and testimonies on animism, the cinematic apparatus, and nonhuman cinematic relations. They convene around an idea of exhibition that keeps spirits, past lives, nonhuman lives, and overall earthly ecologies in mind.

Focusing specifically on the ecologies and histories of plants and cinema, Teresa Castro’s “An Entanglement of Weeds and Film” reflects upon kinship with more-than-human beings, echoing other pieces in this issue that complicate the taxonomy and classification of species. Thinking about the cinematic presence of weeds, plants that are considered somehow minor, constantly excluded from parks and gardens, Castro wonders about the “shared condition” of humans and plants, expanding a sense of encounter to interspecies connections or “attempts to break free from anthropocentric frameworks and observation modes.”

Using the sensorial and haptic response to an encounter with Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour (1959), Arjuna Neuman challenges dominant technologies of viewership with an ontological argument. Using his collaborative filmmaking practice and the conversations and study that both constitute and emanate from it as a wayfinder, Neuman delves into the almost imperceptible substances of soot, glitter, and chrystalline flesh to advocate for a deepened understanding of the potential of political cinema. Clips from Neuman and Denise Ferreira da Silva’s Soot Breath // Corpus Infinitum (2020), interviews undertaken in preparation for the film, and musical echoes or inspiration intercede on the text’s behalf to present other methods of communicating key ideas. “The Glitter Within” acts as a provocation, encouraging the reader to rethink the ways in which the human has been constituted from a biosocial standpoint, and therefore to rethink the technologies that can be used to make sense of the social world.

****

Silences, absences, and the activation of traces

Through our engagement with complex histories of ethnographic encounter, we hope to make clear that just as there are endemic inequalities, so too are there endemic possibilities, through artistic inquiry and radical imaginations, to express oblique forms of relief. Such relief might be sought in the untranslated, the enunciations lost in the colonial urge to represent, and the plural human and nonhuman subjectivities that can be mutually heard without capitulating to a “universal language” of reality. By moving beyond parities of identity, we wish to deprioritize not only those voices that are most audible, but also the mechanics of audibility itself. In so doing, we hope to make room for absence and silence itself, and to honor the subjectivities of those human and nonhuman beings whose voices reach us through multiple attunements.

In dealing with silence and absence, we seek not to dwell on these manifold losses as simple loss, but to scour, to listen for traces, to expand on the nature of active ruins, and—drawing from Saidiya Hartman—to sound out the impossible narratives found inside historical, structural, or “cultivated” silences.{21} For anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot, erasure isn’t a function of recording technologies but rather a condition that frames the terms of encounter. Before the history or description of encounter begins to be written, Trouillot writes, “most often, someone else has already entered the scene and set the cycle of silences.”{22} One task is to go back and locate the subjectivity of communicative and historical silence itself. This requires acts of radical imagination, of sensitive attunements to listening, of attention to noncognitive knowledges. Trouillot writes of the impossible imagination that was necessary to incite the Haitian Revolution: “The unthinkable is that which one cannot conceive within the range of possible alternatives, that which perverts all answers because it defies the terms under which the questions were phrased.”{23} The imagination it takes to overthrow dominant narratives and voices is always unthinkable, even retrospectively. We must learn to inhabit gaps, the places where we can activate absence and the formerly unthinkable.

Just as they remain attuned to past and future silences, the essays in this issue point to ways of representing and materializing the physical absences and vocal diminutions or alterations that remain with us today—those remnants that must be puzzled together with creative and radical force in the ruins of empire scattered all over the world, or what Ann Laura Stoler calls “imperial debris.” These are the ruinations people are left with, what remains after the encounter—the material and social afterlife of those structures, sensibilities, and objects that connected civic life and still quietly vibrate behind the scenes or in the undergrounds and cracks of rebuilt environments. As Stoler puts it, these remnants “reside in the corroded hollows of landscapes, in the gutted infrastructures of segregated cityscapes and in the microecologies of matter and mind.”{24}

To these points, the contributions dwell in the historical ruins of lingual and social dispossession. Elizabeth Povinelli’s essay, “Relations, Obligation, Divergences,” examines nuances within the positions of silencers and the silenced. Recalling her family’s history as Alpine clan people, who after centuries were displaced from Europe only to become settlers in the US, she observes the cycle in which “the dispossessed took advantage of the dispossession of others.” Beginning with memories of a discussion around comparative histories of displacement with a group of Aboriginal women, who would eventually become part of the Karrabing Film Collective, Povinelli’s audiovisual and text contribution is an attempt to parse ways of looking at the fractures and residual fragments of dispossession among peoples, in their differences, for the purpose of mutual rebuilding and reworlding. “For all that connected us—family-based ancestral lands, the more-than-human world; the adjacent historical times of Napoleon’s disenfranchisement of family-based governance in the Alps and of the British settlement of Port Darwin; social and psychic violence that accompanied dispossession and passed down generationally,” Povinelli writes that “we also talked about how the infrastructures of colonialism and racism had sent our shared histories down separate paths.” In other words, fragments and fractures can begin to make possible new “infrastructures of heritability”—that is, the conditions needed to strengthen ongoing anticolonial resistance.

In Syma Tariq’s “Partitioned listening: I hear (colonial) voices,” the absences in the colonial record of the partition of the Indian subcontinent are realized through clipped commentary in the archives. Sentences are cut midway, with debris of hesitations, thoughts, and murmurs filling an absence that, Tariq argues, the colonial record refuses to acknowledge or hold. We are reminded that silence does not exist in the hallowed space of the archive; after Achille Mbembe, we know the archive forestalls our conceptions of history in its very architecture.{25} Instead we hear the materiality of the recorded silence of the archive, sonic artifacts from tape recordings digitized and then played back. Tariq’s piece unfolds as both a sound and text contribution, allowing what is heard and what is said to be in continual relation to each other. Tariq highlights a different definition of encounter here: it is a euphemism for an extrajudicial killing in India and Pakistan, hence another word that silences experience through the historical debris of language.

An oft-repeated line in Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus goes, “There is no mother tongue, only a power takeover by a dominant language.”{26} On the surface, this can be read as capitulation to power, but it also points to the fact that it is not that languages adapt or overcome, but that for many there is only ever the silence produced by having a tongue which is not the dominant language. A “mother” tongue is only ever in difference, the silencing of other forms of communication by the dominant. But we propose that these silences can fill the dominant, through form, reassertion, and multiplicity. To return to Povinelli, “We can focus either on the fractures of memory—and thus on how memory becomes distorted across space and time—or on how these fractures point to the infrastructures of heritability,” and go from there.

{1} Aimé Césaire, The Original 1939 Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, ed. and trans. A. James Arnold and Clayton Eshleman (Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2013), 23.

{2} Enrique Rodríguez-Alegría, “Narratives of Conquest, Colonialism, and Cutting-Edge Technology,” American Anthropologist 110, no. 1 (March 2008): 34.

{3} Arturo Escobar, Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), xxxv.

{4} Dwayne Donald, “On What Terms Can We Speak?” (lecture, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, AB, July 16, 2010).

{5} Mario Blaser and Marisol de la Cadena, “Introduction. Pluriverse: Proposals for a World of Many Worlds,” in A World of Many Worlds, ed. Marisol de la Cadena and Mario Blaser (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 5.

{6} André Leroi-Gourhan, “Note sur les rapports de la technologie et de la sociologie,” L’Année sociologique, 3rd ser., 2 (1949): 767. Translation by Counter Encounters.

{7} Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, “The Image of Objectivity,” in “Seeing Science,” special issue, Representations, no. 40 (Autumn 1992): 83.

{8} Daston and Galison, 83.

{9} Eadweard Muybridge’s chronophotographs were the result of a commission made by robber baron Leland Stanford, who wanted an accurate representation of a horse’s running motion. See Rebecca Solnit, “The Annihilation of Time and Space,” New England Review 24, no. 1 (Winter 2003): 5–19. Solnit details the convergence of scientific research, the California railroad industry, and the invention of cinema.

{10} See Tilman Baumgartel, “The Civilizing Cinema Mission: Colonial Beginnings of Film in Indochina,” in Early Cinema in Asia, ed. Nick Deocampo (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017), 179–206.

{11} Katherine Groo, Bad Film Histories: Ethnography and the Early Archive (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019), 63, 64.

{12} In France, the Lumières’ native country, Jules Ferry (the same politician who, in 1882, established free, secular, and mandatory public education) stated, in an 1884 speech to the Chamber of Deputies, “Higher races have a right over the lower races. . . . They have the duty to civilize the inferior races.” See “Jules Ferry (1832–1893): On French Colonial Expansion,” trans. Ruth Kleinman, Modern History Sourcebook, Fordham University (website), accessed October 11, 2022.

{13} “Civilizing mission” is also a term from Jules Ferry’s 1884 speech. In France, the colonial archive at the Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée (CNC) conserves around 820 colonial documentary films and 300 fictions.

{14} Groo, Bad Film Histories, 58.

{15} Pablo Mora’s definition of audiovisual sovereignty is relevant here: “[An] idea of consolidating the position of Indigenous peoples through image and public communication, [an idea] that is not new and has a long history in Latin America, structurally related to indigenous agendas of social transformation and cultural citizenship.” Pablo Mora Calderón, Máquinas de la visión y espíritu de indios (Bogotá: Idartes, 2018), 93. Translation by Counter Encounters.

{16} Baptism in the piece doesn’t refer to the Catholic ritual but to a spiritual initiation and acceptance led by the mamos.

{17} Sylvia Wynter, “On How We Mistook the Map for the Territory, and Reimprisoned Ourselves in Our Unbearable Wrongness of Being, of Desêtre: Black Studies Toward the Human Project,” in A Companion to African-American Studies, ed. Lewis R. Gordon and Jane Anna Gordon (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 134.

{18} Since 1492 is the year of Columbus’s voyage, Wynter understands it to be the start of the colonial period. See Walter D. Mignolo, “Sylvia Wynter: What Does It Mean to Be Human?,” in Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis, ed. Katherine McKittrick (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 111. On the problem of overrepresentation see Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument,” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (Fall 2003): 267.

{19} Sylvia Wynter, preface to We Must Learn to Sit Down Together and Talk About a Little Culture: Decolonising Essays, 1967–1984, ed. Demetrius L. Eudell (Leeds, UK: Peepal Tree Press, 2022), 14.

{20} Beverley Best, “Postcolonialism and the Deconstructive Scenario: Representing Gayatri Spivak,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 17, no. 4 (August 1999): 476.

{21} Among other writings and speeches, see Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 11.

{22} Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), 26.

{23} Trouillot, 113–14.

{24} Ann Laura Stoler, Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), 9–10.

{25} Achille Mbembe, “The Power of the Archive and Its Limits,” in Refiguring the Archive, ed. Carolyn Hamilton et al. (Dordrecht, Holland: Springer Science+Business Media, 2002), 20.

{26} Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 7.