Relations, Obligation, Divergences

Elizabeth A. Povinelli

Relations

In 1984, I was sitting at the edge of Madpil, an estuarine creek located across the Darwin Harbour in the Northern Territory of Australia, with several Belyuen women, including Marjorie Bilbil, Alice Wainbirri, Gracie Binbin, and Betty Bilawag. The Belyuen community sits in the middle of the Cox Peninsula. During the unbearably humid months before the monsoons begin, everyone there spends as much time as possible on nearby beaches. And so it was with us on that hot, languid November day.

The women were just getting to know me, and I them. We had met in October after they approached me at a little beach camp where I had pitched a tent in front of the old, musty Mandorah tourist hotel on the northeast corner of the Cox Peninsula. The local white school principal had told them that a young white woman from America interested in Indigenous philosophies was camping there. I had already met one of their male cousins on my first motorcycle trip from Darwin to Mandorah. My fuel tank was running low, so I pulled into the Belyuen shop, came to a stop, and asked an older man sitting on its veranda, “Do you know where there is a gas station around here?” “There isn’t a gas station in all of Australia,” he replied. I paused, a little stunned, even panicked, for a moment. With perfect timing, Tommy Barradjap, whom I would subsequently come to know, added, “But if it’s petrol you’re after, then head down the road to the Mandorah pub.” Another fifteen kilometers found me rounding the corner past the Mandorah wharf and onto the property of the hotel, where Indigenous customers had to purchase beer and food in the back, as non-Indigenous tourists and local residents ate and drank in the front. I came back a few weeks after meeting Barradjap, trading cleaning work at the hotel for a camping space on the beach. Two weeks after the women initially approached me, Marjorie Bilbil came back, proposing that I move into the community in order to help her and the other women write grants to raise money for a child crèche at the Belyuen Women’s Centre. As was then a very common means of socializing stray white people, I was quickly absorbed into Bilbil’s family and, from there, into the network of kinship that unfolded around her, a kinship that included specific relations with the human and more-than-human world.

While we waited for the fish to bite, Betty Bilawag sketched, as she often did, a series of named places in the sand that defined the vast coastal region of Belyuen families—an area that Darwin settlers described as the lands of the Wagait.{1} She outlined which families belonged to which places, how they were connected to nearby totems, how the country responded to different human languages and sweat, and how each place was connected to other places through relations of totemic action, marriage, and ceremony. The spatial location and shape of the named places she sketched were exceedingly important to her. She would often drill her kids, and me, on what she sketched—insisting we create mental maps of the places and their relation to their ancestral stories, based on wherever we were standing. “OK, well, you are standing here, so walk down that way [in your head] and tell me what you see.” I would eventually travel to these places before the last of these elder women died—each time it was a revelation, like meeting a relative you had heard so much about but never seen.

When the women asked where in America I came from, I would sketch in the same sand a line that moved from the Alpine village Carisolo, in the province of Trentino, where Povinelli first emerged as a nickname sometime in the late 1400s, became a surname by the mid-1500s, and then split into clans, including my Simonaz clan of Povinellis, in the late 1600s; to Buffalo, New York, where our clan began immigrating in the late 1800s, and where I was born in 1962; to Shreveport, Louisiana, where I grew up; to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where I got a BA in philosophy; finishing with “right here,” which was wherever we were at the moment. When they said, “So, your family is Italian,” I would recount stories of family fights that broke out over this very question, given the location of our village at the frontier of city-states, nations, and empires since the time it was founded. And I would describe how the arguments often ended with a détente over minimally agreed truths—that the various clans of Povinelli, Ambrosi, Bertarelli, and Maestri were among the original families of Carisolo; how they were forcibly converted to Catholicism; and how they were disenfranchised when Napoleon invaded their region in the late 1700s. I described the stories I’d heard them tell us about their cows, bred especially for the high-altitude pastures and serving as a source of warmth in the bone-cracking winter cold; about the icy creeks my grandfather fished; and about their culinary memories of the deer, mushrooms, and chestnuts found in their forests. And I described how this relation to the more-than-human world was passed down to me and my siblings. How we grew up foraging for food across the woods that surrounded our Shreveport home.

“So, you’re from mountains but then you moved to America?” they summarized.

The dispossessed took advantage of the dispossession of others.

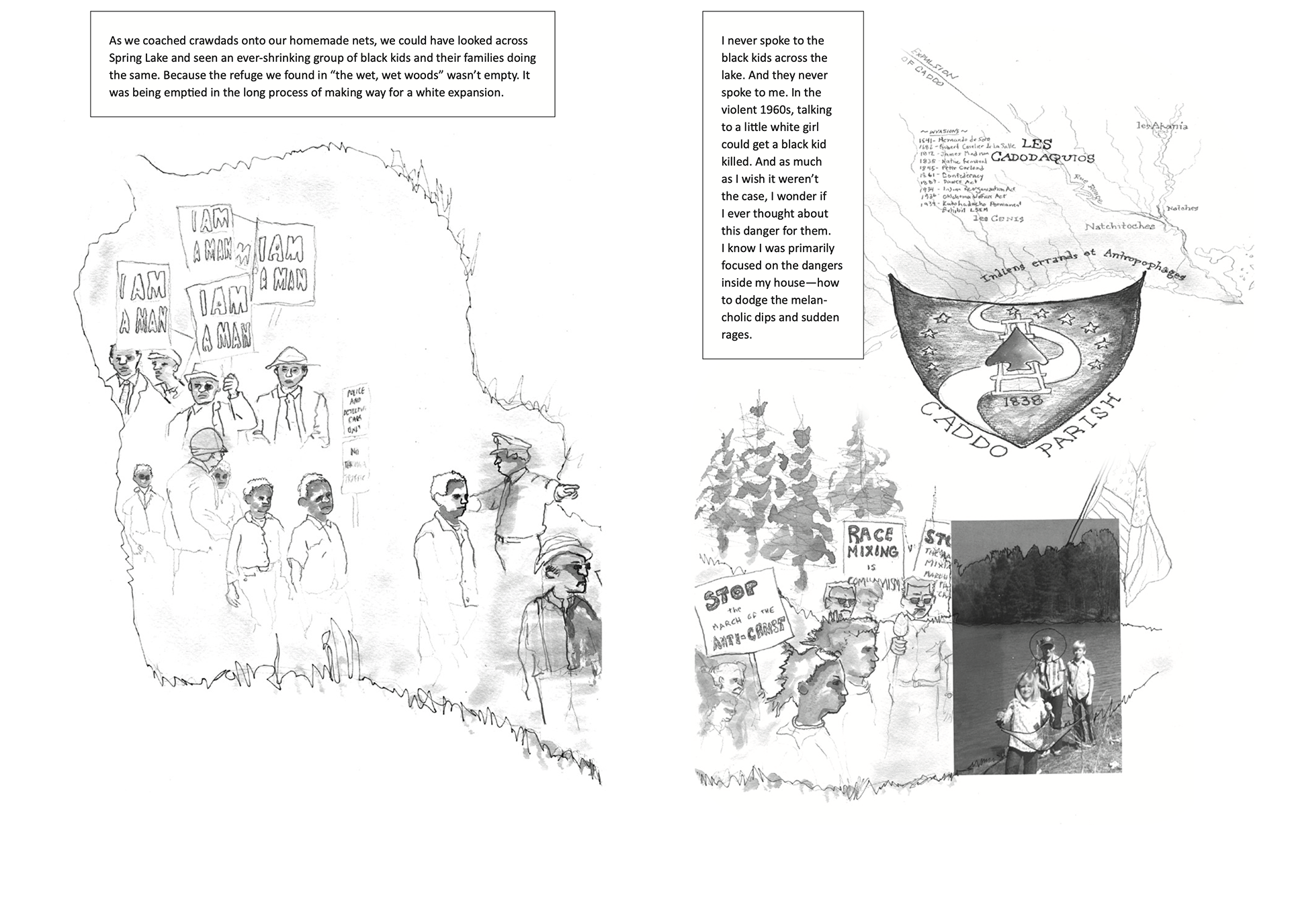

THE INHERITANCE (Alice Henry Ink, 2021).

From the very beginning, in other words, histories and forms of dispossession and practices that countered them were in the front and center of our conversations, as they continue to be with these women’s children and grandchildren. These women’s narrative styles ranged widely, but they were often extremely wry—ripping into the bodily deformities of white settlers who sadistically rampaged across the landscapes of their youth. They could also turn pensive. Years had gone by from that lazy November when some of the same people were assembled on the veranda of the Belyuen Women’s Centre, listening to a tape recording of the melancholic wangga by Eliang, a deceased Emmiyengal man.{2} In my notebook I wrote down the Emmi lyrics: ngama nganitudunu ngabarrunu theme ngananthi. They translated the lyrics as “I am standing here. I will follow my track back to where I came from,” describing the mood in the song as “worried”—would he be able to find his way home? When we finished, a quiet descended on us. At some point, Marjorie Bilbil began to speak about a melancholia she sometimes saw overcome her relatives. She didn’t use the word melancholia. She said they sat down quiet, thutmahl, malhwai (closed word, no words; refusing or unable to speak). Sometimes, she said, her mother and father would then begin to cry as the seasons turned and they were unable to return to their southern ancestral lands. Others shared similar stories.

The women’s parents—some of whom were still alive—knew the paths to the places Bilawag sketched in the sand. But they had been born some thirty years after settlers first came to Darwin in 1869. The ramifications of the Darwin settlement were felt down the coast as settlers shot and poisoned Indigenous people in the drive to appropriate their lands. They still traveled with their own parents, who followed the tracks created by their totemic ancestors, paths continually renewed through practices of marriage and ceremony and the ordinary interactions they had with their more-than-human worlds.{3} This changed when the Delissaville settlement—renamed the Belyuen community in 1976 after the passage of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act—was established in the late 1930s as a government internment camp. Its purpose was to stop, contain, manage, and ultimately assimilate the Wagait people. This mandate made Delissaville just another node in a global system of settler governance meant to disconnect people from their ancestral relations through forced settlement onto government and missionary camps, and through the removal of their children to boarding schools.{4} Marjorie’s mother and father were part of this forced settlement. Of course, many refused to be spatially restricted, escaping for days, weeks, or months or manipulating settlement supervisors to send them to other camps. Many others continued to pass down to their children their analytics of existence and the narratives and ceremonies that kept this existence in place. Nevertheless, finding a way of getting to distant ancestral lands, some three hundred kilometers by foot, was often impossible. This is why they wept, said Marjorie. They worried they would never be able to find a path back.

I remember thinking about my paternal grandmother that day; her severe depressions that followed the years she left Carisolo with my grandfather Povinelli to raise their family in Buffalo; the crude electroshock therapy she received to snap her out of her obsession with the village; how she seemed to lose her mind as she lost the place that constituted her identity. I may have said something. I may not have. The historical trajectories of their parents and my grandmother seemed so close they could almost meet if viewed from one perspective. But when viewed from another, they diverged radically. For all that connected us—family-based ancestral lands, the more-than-human world; the adjacent historical times of Napoleon’s disenfranchisement of family-based governance in the Alps and of the British settlement of Port Darwin; social and psychic violence that accompanied dispossession and passed down generationally—we also talked about how the infrastructures of colonialism and racism had sent our shared histories down separate paths.

We constantly encountered these differences.

THE INHERITANCE (Alice Henry Ink, 2021).

THE INHERITANCE (Alice Henry Ink, 2021).

While today the drive from Belyuen to Darwin takes about an hour, and the ferry to the Mandorah wharf about fifteen minutes, in 1984 the ferry chugged across the harbor for forty-plus smog-choking minutes—if one could afford the ferry ticket. The road connecting Belyuen to Darwin was still nothing more than pounded dirt. The 150-odd kilometers that separate the spaces were then a treacherous two-hour drive, the road often becoming impassable during the yearly, then more regular, monsoons. The white population on the Cox Peninsula was tiny—some fifty residents—and hugged a strip of coastal land facing Darwin. Belyuen had a population of about 250 people. All of this meant that the older women knew the origin, meaning, and shape of nearly every sound in their environment, including the identifying sounds of various cars and trucks. When we were out fishing or hunting, they would quickly assess the owner and direction of vehicles heard across the breeze, bouncing off the trees, or announced by the sudden disturbance of animals and birds. If it was from the Mandorah community—or registered a more alien sound—the women would insist that we pack up quickly and leave. And if they said, “Leave everything, run,” they meant don’t worry for your things; worry for your life. When I first asked why, they replied, “Berragut [white men] coming. They will shoot us.” My first reaction, as I ran side by side with them, was, They can’t just shoot people. But I was someone who had been able to pitch my tent along the white beaches of Mandorah.

We were running alongside each other, but we were not, could not simply and without reserve, run as if we were the same target.

Ever since these conversations, I have sought to understand the cascading relations of affiliation and difference that have emerged among us as our clan-based families entered and moved through the history of settler colonialism, the Black Atlantic, and the Indigenous Pacific. What kind of politics emerges from such a scene—a running from the violence of settler dispossession when one of the people running is within the category the others are running from? If syntax bends back on itself as it attempts to describe such a scene in some sensible signifying chain, our theoretical and political approaches may well also have to. The relational obligations that opened in 1984 had to place both the shared and differentiated in the same frame. And they, too, knew the ways settler colonialism inserted divisions into their own modes of social belonging, the divisions of capitalism, property, color, and religion such that older modes of solidarity were undermined.

****

Divergences

affects

I started making the specific drawings for The Inheritance some fifteen years after our afternoon at Madpil. The Inheritance is a three-act play probing the visual and affective effects of multiple, socially nested forms of “little Elizabeth’s” family’s Trentino dispossession as she experiences them in the segregated US South of the 1960s and 70s. It, and a film based on it, are first elements of what I have been calling the Heritability Project. This project is simple in form and purpose. It tracks the fate of a set of clans in the wake of Western forms of freedom, white supremacy, and settler colonialism—my own Simonaz clan of Povinellis from Carisolo, Trentino, and some of the clans of the Karrabing Film Collective whose lands stretch across the northwestern coastal region of the Top End of the Northern Territory, Australia. The project uses a series of rhyming historical events, images, and ecological conditions to demonstrate how initially similar subnational, family- and clan-based modes of relation to land and its more-than-human worlds are diverted as they are differentially folded into the unrelenting infrastructures of colonialism and racism. The purpose is to get ahead and around Right and Left rhetorics of white nativism/Indigeneity sprouting in the US, EU, New Zealand, and Australia, all places that clans from my village left for, starting in the 1870s, just years after Darwin was established as the first British colony in the far Australian north.

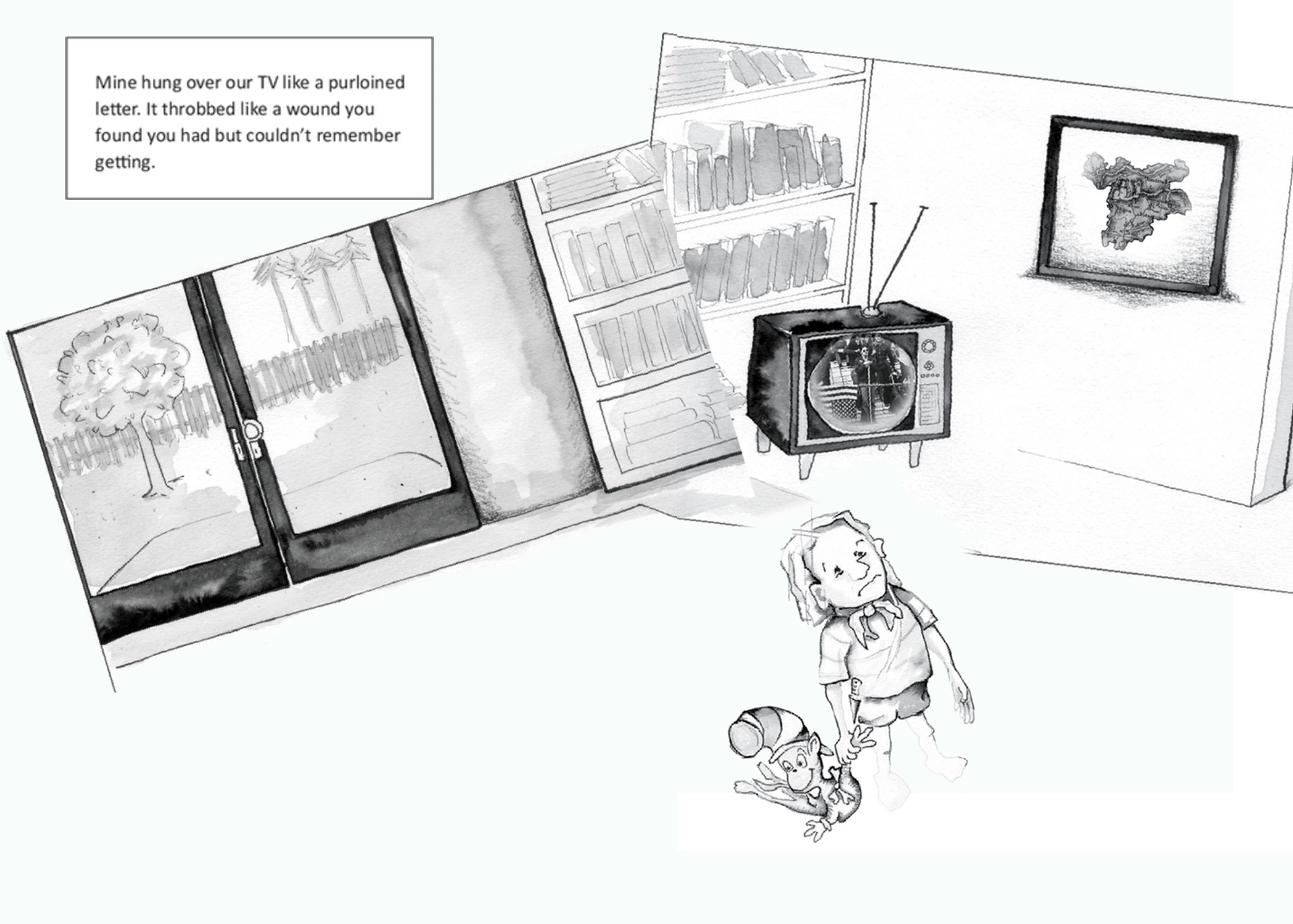

The first act of The Inheritance opens as if it were a conventional ethnic memoir, with images of little Elizabeth struggling to understand the meaning of a framed image hanging on the wall of her Louisiana home—a topological map of the Alpine location of her ancestral village, Carisolo. The second act moves to the histories her grandparents tell her of how and why her Povinelli clan left its village for the United States, even as they insist that she never forget that she is Simonaz Povinelli, from a place no one agrees about how to pronounce—Carisolo in the Italian pronunciation, or Karezol in the Austrian. Riffing on Chekhov’s reflection that if there is a gun on the mantelpiece in the first act it must go off in the last, the third act turns the problem of inheritance away from the ancestral past and to the ancestral present. What is little Elizabeth’s inheritance if we situate it in the US, and more specifically in the American South of the mid-1960s, when her family moved from Buffalo, New York, to Shreveport, Louisiana? The same year they moved, the US Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, which would supposedly prevent discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in hiring, promoting, and firing, in public accommodations and federally funded programs, and in the desegregation of schools.

THE INHERITANCE (Elizabeth A. Povinelli, 2021).

THE INHERITANCE (Elizabeth A. Povinelli, 2021).

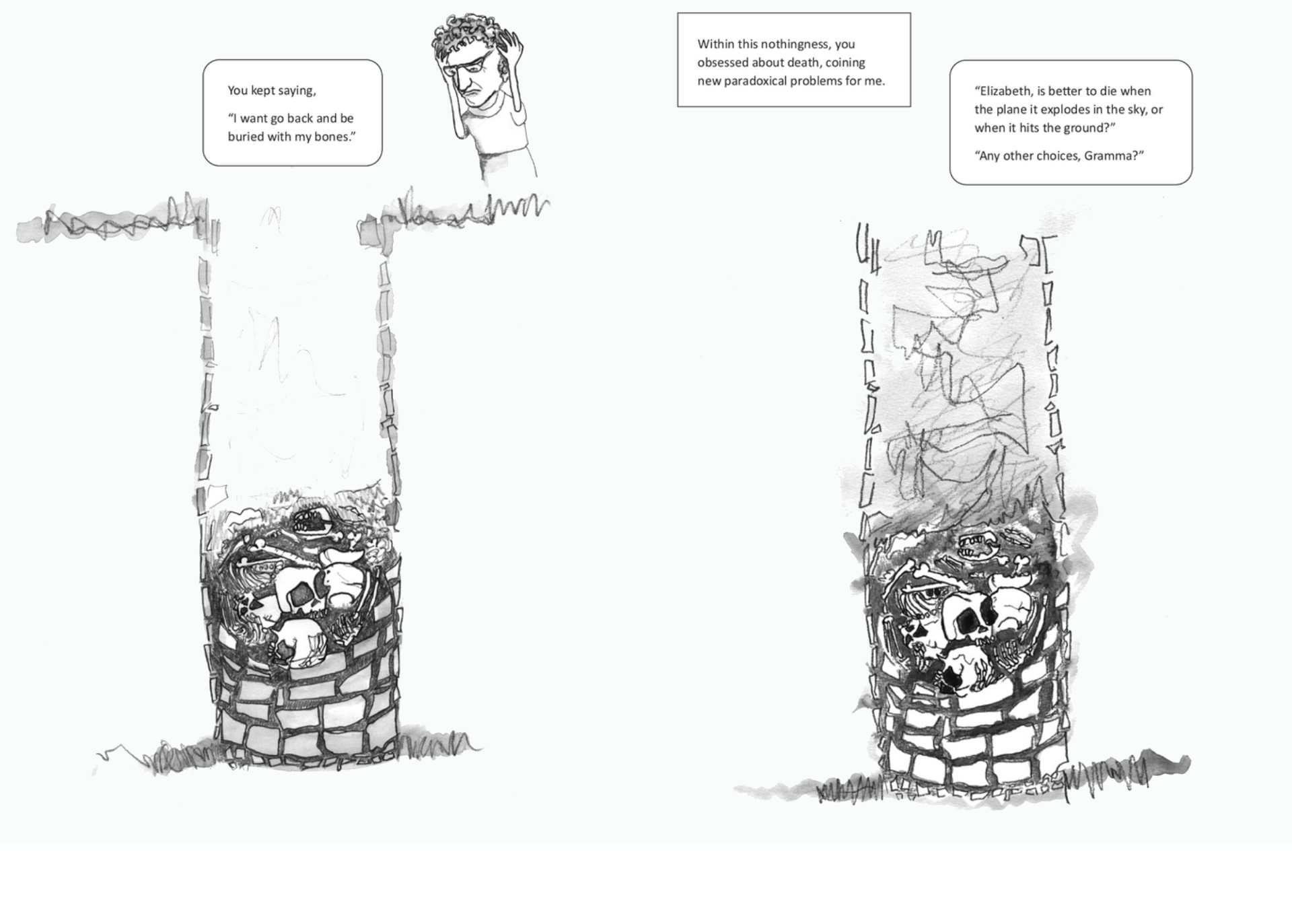

Attachments form before reason can rule the why. (“I was probably six or seven before it began to stand out from all the other items inside and outside our house—before it became strange to me in its difference from everything else.”) The artistic question is, of course, how to draw readers into a visually confusing background that conditions how little Elizabeth inherited my family’s affective relation to their village lands. What form of image-making might replicate the affects of familial loss, predating narratives about the what, where, why, and how of the loss—especially when these affects have no narrative anchor, or too many divergent and incommensurate narrative anchors? Could I draw my way into the melancholia of dispossession that cast a pall over my Povinelli family—the melancholia of their stubborn, relentless refusal to let go of an identity, of an identification with their ancestral village, long after it had been lost, and no matter the personal consequences?

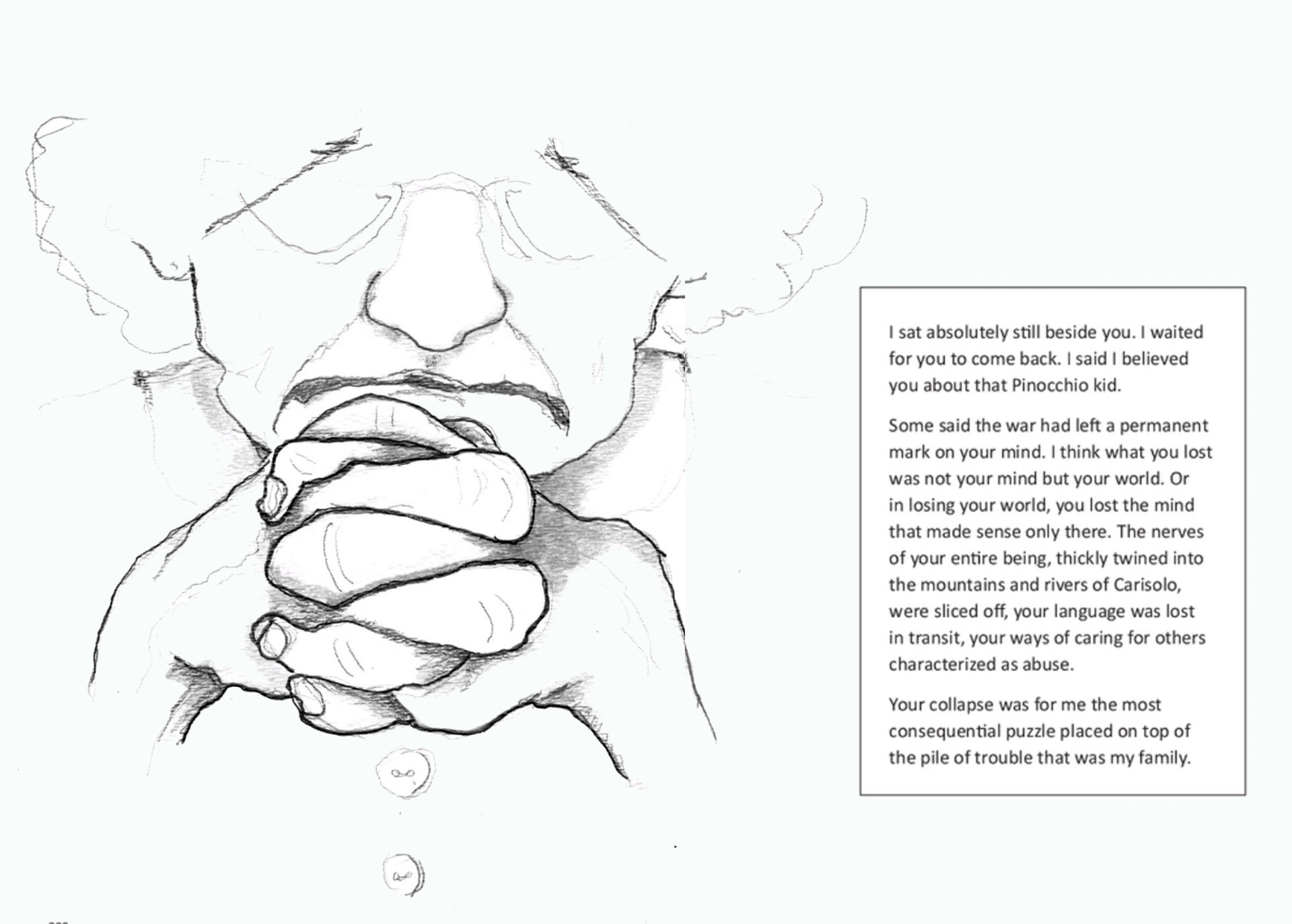

“Act II: Gramma” is the technical heart of the melancholic refusal that anchors the first two acts. It tells my story of my grandmother’s story—how she came from one of the other original families (Ambrosi) of the village and thus with a history passed down from her parents and grandparents of being at the heart of the vicini, who had been disinherited of their rights of self-governance when Napoleon first invaded the Trentino region in 1796, then declared the end of the carte di regola in 1805. The carte di regola was an institution of patrifamilial (capifamiglia) rights of self-governance of vicini over who could use community lands and resources, and how—how they regulated the pastures and forests, the time of their lives, and the times of the Alpine ecology. Napoleon claimed to be carrying modern civilization in his military carts as he climbed over the Alps. Hegel claimed he was bringing more than that—that Bonaparte was the historical personification of Geist unfolding universal mutual human recognition as he bombed his way across Europe. The Geist Napoleon and Hegel supported had a limit—liberty, fraternity, and equality presupposed a hierarchy of Life, its absolute difference from Nonlife, and its pinnacle as occupied by European Man. The liberation of Man had a universal reach only if the Haitians struggling for freedom under the wing of Toussaint L’Ouverture were expelled from the human. The Haitian Revolution, like the numerous fights of First Nations against colonial violence, made clear, if clarity was still needed, that the grid of intelligibility was organized not on human nature but on dispossession.

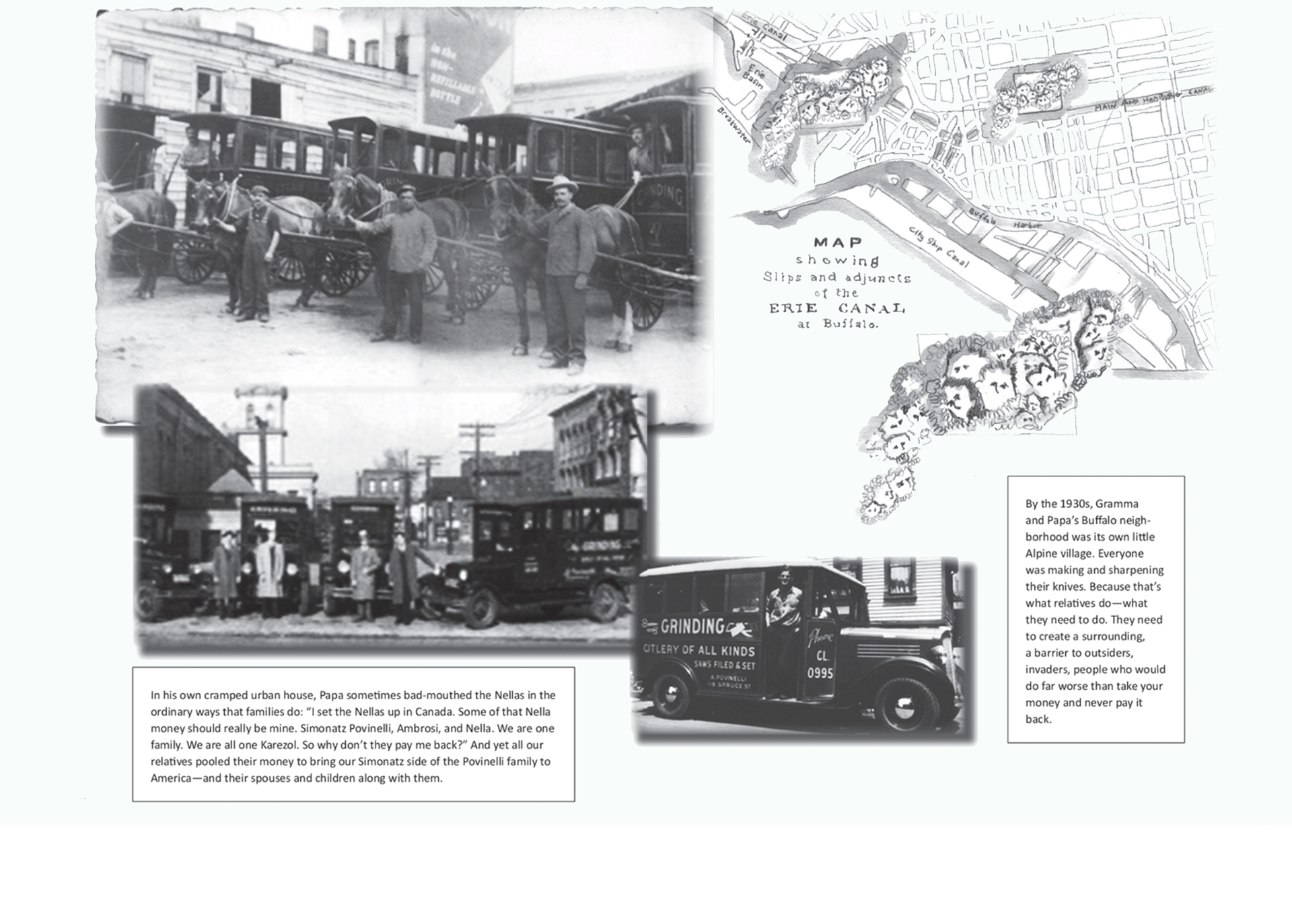

Gramma is the shadow cast over her family’s collective ego of these lost relations with these spectral orders, severed long before her parents began plotting with her eventual husband’s parents to create knife-grinding businesses in Buffalo, New York. The frontier violence she witnessed was the war of position between Italy and Austria-Hungary in Trentino and South Tyrol during the mid to late nineteenth century, which broke into a war of maneuver during the First World War.{5} When her family packed and left for Buffalo, they brought with them hopes—that an easier life could be forged in the US and that thick village ties could be replicated by clustering the families in a Buffalo neighborhood. When Gramma’s nieces, nephews, and grandchildren moved away from the neighborhood and city this second hope collapsed, and with it Gramma’s psyche. She used to say to me, “Elizabeth, this America, it takes my children from me and gives me nothing. All my family is far away from here.”

The melancholia of dispossession that engulfed my grandmother overlaps so closely with Freud’s understanding of the melancholia of modern subjectivity that we might be tempted to overlook their differences. Freud sees melancholia and mourning as two distinct psychic phenomena. Mourning, for Freud, is a conscious activity while melancholia is not. In mourning, one knows what one has lost and so undergoes the slow and painful, but ultimately successful, project of withdrawing cathectic energy from the lost object and redirecting it to a new object. Melancholia doesn’t allow for this. For Freud melancholia is a pathological condition that emerges when a narcissistically selected love object is lost. The loss collapses the ego into the thing; the subject is unable to detach from it without detaching from herself, because what she picked to love was a version of herself.{6} What might Freud make of Gramma? Her attachment to the village was neither unconscious nor technically narcissistic. When Gramma descended into a bout of crippling depression, she was told to forget about the village; to focus on America; to find new forms of interest. These statements were, however, disingenuous. Grandpa Povinelli spent his life fuming about a set of personal slights regarding the legitimacy of his status as a Povinelli, which started in the village and followed the families across the Atlantic. What they might actually have been saying was, Take a specific emotional stance toward this lost object—an active stance of ferocious outrage, and the ongoing presence of loss.

Crucial to Gramma and Papa Povinelli’s attachments was the way they circuited through family-based modes of belonging, as well as national ones. The identification with Carisolo was not grounded in the socially deracinated subject of liberal self-possession. To be a Simonaz Povinelli from Carisolo was not to be a part of the dialectic that Marx saw emerging in liberal-secular nationalism—namely, the dialectic between common, homogenized state-based citizenship and the self-possessions of individual labor, belief, and love.{7} In this liberal-secular model, the psychic dynamic of Freudian melancholia might make sense. The ego is locked within a battle between the pleasure principle of the id and the repressive principle of the superego. But in Gramma and Papa’s case, their “I” was always already conditioned by the statements “as an Ambrosi” and “as a Simonaz”—“I” as an Ambrosi from Carisolo. This conditioning of the ego was not chosen. In other words, Freud’s narcissistic subject presupposes the so-called liberation of the subject from these prior conditions—we can call this so-called liberation Napoleon. But unlike Hegel, who heard in Napoleon’s cannons at the gates of Jena the symphonic unfolding of universal mutual recognition, Gramma’s and Papa’s parents and grandparents heard nothing more than another wave of violence washing over their lands. Their refusal to be dispossessed was symptomatically expressed in a refusal to be socially deracinated. Even as they took advantage of settler colonialism, my paternal grandparents refused to break the relationship between their family-based self and the lands they left after having been dispossessed. Displaced but not detached, my grandparents died in a stubbornly conscious embrace of their village. Refusing to let go of something we had never known, my grandfather drew us deeper into the family melancholia.

THE INHERITANCE (Elizabeth A. Povinelli, 2021).

THE INHERITANCE (Elizabeth A. Povinelli, 2021).

While The Inheritance is situated within the affective worlds of my grandmother Ambrosi and grandfather Povinelli (clan: Simonaz), it is not about them. Aristotle thought that tragedy was most likely to produce a moral catharsis when it was centered on “people closely connected, for instance, where brother kills brother, son father, mother son, or son mother—or if not kills, then means to kill, or does some other act of the kind.”{8} But tragedy’s pathos comes not from what has happened, but from “the sort of thing that would happen.”{9} The deep link between poetics and philosophy, and their difference from history, arises from exactly this. In tragedy, we are asked to reflect on what could always happen because of the way things are. Catharsis is the name some give to the affective register of this mode of thought—the feeling that everything that shouldn’t happen is inevitably happening again. Reflection is the name we give to questions that arise in its wake. The questions arising from The Inheritance might be: What could have been, could be, avoided? Was this tragedy caused by the nature of the relationships between persons and this kind of place-based attachment/dispossession, or just the choices these specific people made about how to live with this history? Couldn’t they just acknowledge the problem they face and find better solutions? Isn’t this what mass-marketed mindfulness programs promise? And even if Aristotle is right, and tragedy pivots not on character but on the actions in which we find and reveal ourselves, couldn’t they have just made better choices about their actions—perhaps helped along with an economy of nudges? The Inheritance tries to wedge itself within these potential reflections as readers move across the family train wreck, where every action elicits a reaction, and “where every reaction becomes a chain reaction and every process is the cause of new processes.”{10}

We can focus either on the fractures of memory—and thus on how memory becomes distorted across space and time—or on how these fractures point to the infrastructures of heritability.

A longtime reader of Aristotle’s Poetics, Lauren Berlant proposed the bitter pill of cruel optimism as a path into understanding not merely these kinds of train wrecks but certain affective and reflective reactions to them. For Berlant, the tragedy of conceiving tragedies as “lessons we can learn from” is that this approach fosters cycles of repetition. Cruel optimism mistakenly diagnoses character rather than action as the problem; or understands actions as concatenations of the individual decisions of more or less mindful subjects. The optimistic side of cruel optimism derives from a person believing that she can avoid tragedy by picking better, being more mindful of her individual actions and intentions, and focusing on the future where anything is possible if she just tries harder. The cruelty of such optimism is that it reiterates rather than alters the social systems that shape, channel, and valuate the plots our lives follow. Berlant saw a specific form of cruel optimism besetting US and European neoliberal citizens in the 1980s. Or, more specifically, besetting those citizen-subjects to whom the social democratic promise of postwar flourishing was addressed.{11} Gramma was promised something like this before the Second World War. But the fulfillment of these promises became the grounds of her radical disorientation and decomposition as her children left the neighborhood.

****

If tragedy comes not from what has happened (i.e., something from the past), but from the sort of thing that could have happened (i.e., how things tend to go in the future imperfect), then what are the different imperfect futures into which my Povinelli-Ambrosi family faced and into which the clans of the Karrabing face?

About fifteen years after our fishing trip to Madpil, some of the women’s descendants and I started the Karrabing Film Collective. By 2015, we had completed our second film, Windjarrameru: The Stealing C*nt$. The plot is simple. Four young Indigenous men find two cartons of beer near a sacred site where a mining company is illegally blasting. A standoff ensues at the edge of a toxic swamp among the police, mining officials, and the local Indigenous community. Within the swamp, the four young men reassure each other that, even if they die from toxic exposure, they will be following their fathers back into their country; this is a better outcome than being locked away in prisons for a crime they did not commit. Three years later, our sixth film, Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland (2018), depicts the near future as a world in which settlers, in their quest to accumulate anything and everything of value, have so wrecked the environment they can no longer safely go outside. Indigenous people can and are still living on their lands. What do settlers do in such a world? They try to save themselves by extracting minerals from Indigenous lands and using them to experiment on Indigenous children. If there is tragedy here it comes not from the “virtuous and purifying” actions of the protagonist, Aiden, at the end of the film, but from what Gavin Bianamu noted when we began sketching out the film’s backstory. “This is what berragut [white people] would do; this is what they are already doing.” This is the “sort of thing that would happen” because, as is hammered home in the musical refrain of the Karrabing Film Collective’s Day in the Life (2021), this poetic plot emerges from the everyday actions of settler capitalism.

WINDJARRAMERU, THE STEALING C*NT$ (Karrabing Film Collective, 2015).

Thus, if you are Indigenous, or are in an intimate relation with Indigenous lives, you are very likely to know who will go to prison the first moment you see the conflict appear in Windjarrameru. And if you are one of these kinds of people, then you could have guessed what berragut would do even after the consequences of their destruction of everything have come home to roost. You know because these are the cruel repetitions that define the sort of things they already do. At the edge of the mud place, Aiden’s uncle tells him that if he releases the blow flies, “everyone dies. Everyone, black and white.” To this Aiden notes, “We are already dying. They are already killing us.” In Day in the Life, Rex Edmund raps that he used to drink and smoke but now takes kids into the bush to teach them ancestral ways. But when he is taking his nephew Gavin, they run smack into an illegal lithium mine. They are already killing us. They do that. That’s what they do. They rip their ravenous teeth into the fabric of every human and more-than-human relation they find and then stand with their lips hanging down when the world returns the favor. The consequence on existence is tragic even as berragut are portrayed as ridiculous creatures.

DAY IN THE LIFE (Karrabing Film Collective, 2021).

When we pivot The Inheritance against these Karrabing films the relationship between various forms of catharsis and modes of heritability and dispossession come to the foreground. We begin to see that melancholia is not an indiscriminate pathological condition, but differs between, on the one hand, how it works within the ideologically deracinated subject of liberal self-possession, who has been promised she can swallow and spit out an endless series of others as she looks for someone to walk hand in hand with down the aisle of her future flourishing; and, on the other hand, how it works within those who inhabit their subjectivity as an irreducible relation with specific others and places—whose sense of the self and place comes through their ties of obligated kinship. The remedy for the first kind of melancholia is said to be more and better severing: become more mindful, self-absorbed. The remedy for the second is the hard work of reconnection. In The Inheritance and the Karrabing films, we also begin to see the different grounds of catharsis within the tragic pathos of settler colonialism—between those who think that a different ending is possible even as they cling to the social relations that produce the plot; and those who know no other ending is possible until these social relations are fundamentally transformed. A final thing we see is that the effects of dispossession depend on one’s relation to the cruel optimism of settler late liberalism. The four young men’s stance toward liberal toxicity is grounded in the irreducible nature of their kinship with the human and more-than-human world. My paternal grandparents’ refusal to give way to a history that had long left the village behind was grounded in this same irreducibility. But by the time I entered the scene, their irreducible grounds were bounded by the gift of white self-flourishing at the expense of others.

****

narrative location and tense

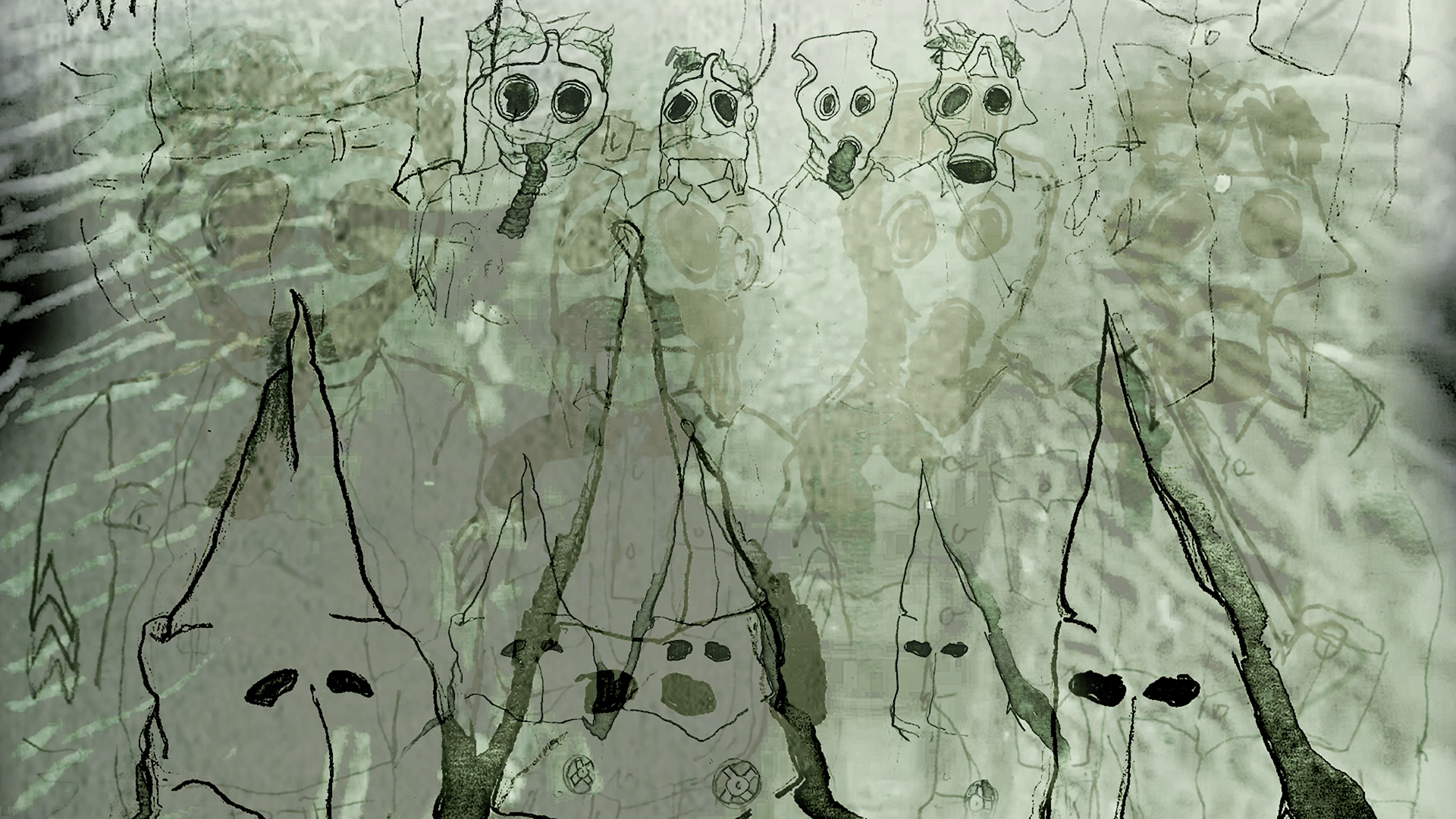

If the graphics of The Inheritance are oriented to the affects of dispossession, they are also oriented to the social semiotics of sensemaking. Double images are common—in the film they manifest as layered images and videos. The doubled images include different referents for the same statement and different foregrounds and backgrounds to the same situation, depending on whether one is looking at the Povinelli family or national racial drama. For instance, in the first case of double images, little Elizabeth is shown mistaking her grandmother’s stories about Carisolo for things she is experiencing in the violent struggles between white supremacy and civil rights activists in Louisiana. When her grandmother warns her to always watch out for the men in hoods with guns, little Elizabeth says she has seen them in the woods around her friend’s house. Her grandmother is referring to the soldiers in gas masks; little Elizabeth to Klu Klux Klan rallies. Gramma’s visual reference is distributed across and reorganized by the new social situation that defines little Elizabeth’s visual field. Even as grandchild and grandmother feel an intimate embrace around danger, they stray far afield from each other. These split references are used not only to demonstrate how the interpretative content of inheritance fractures and fragments across social landscapes, but also to open a question about what, when, and where inheritance is located. Her grandmother experienced the guns as aimed at her. We can focus either on the fractures of memory—and thus on how memory becomes distorted across space and time—or on how these fractures point to the infrastructures of heritability.

This latter way of viewing the doubled images helps to make sense of how images backgrounded in the beginning of the book are foregrounded at the end. On the television and in documents throughout the first two acts, readers see an American drama unfolding around little Elizabeth’s family as it remains obsessed with its historical connections to a village. As the narrative progresses to act 3 and the heat of the problem turns from the ancestral past to the ancestral present, these public cultures push their way to the front. Scenes of Native American protest met with police violence are playing in the Povinelli television in the first act, but become the focal point of the third. The visual inversions between act 1 and act 3 are meant to dramatize the difference between examining inheritance and heritability from the point of view of the ancestral past and from the ancestral present. Whatever Gramma experienced, by the time she was speaking with little Elizabeth, the scenes of violence had shifted. If we begin where little Elizabeth actually lived, then her inheritance lies within the social worlds of Shreveport, Louisiana, within Caddo Parish, where the Caddo were forcibly removed to Oklahoma in 1859, which was ten years before Darwin was settled, and about forty years before my family began moving out of Carisolo and onto the lands of the Seneca (Buffalo, New York).

THE INHERITANCE (Alice Henry Ink, 2021).

THE INHERITANCE (Alice Henry Ink, 2021).

All of these imagistic and narrative games attempt to drive home an argument that inheritance expresses itself in material sedimentations of bodies and places in the ongoingness of the ancestral present. For instance, as my father drove us across the US in the summers to show us that America was bigger than the South, he drove us on the interstate highways—then new, now crumbling—that white people made by blasting through Black neighborhoods and Indigenous lands. The terraforming of lands as materials was an extractive process, and redistributed so that this colossal transportation network targeted Black and Indigenous neighborhoods and lands, as did industrial toxicities. We didn’t drive on socially agnostic roadways. We drove toward the infinite horizon, moved forward by white dreams of endless flourishing.

Though less emphasized in The Inheritance, the social tenses of dispossession are crucial in any conversation about the stakes of Right and Left dreams of a return to pre-Christian white nativism based on lost rurality, oneness with the landscape, and modern antimodernism. As my family zoomed down the US interstate, we embodied an orientation to the future perfect crucial to the functioning of European exceptionalism. White US and European liberal capitalism have long used temporal and spatial horizons as means of sloughing off their ongoing harms while assigning others, such as the women I sat with at Madpil nearly forty years ago, to a frozen past.{12} Now these same European diasporic worlds, having swallowed the earth as they marched toward their shiny future, want to claim an unblemished past as well.

****

Obligations

In 2019, Linda Yarrowin, Rex Sing, Aiden Sing, and I traveled from a Karrabing event in Paris to Carisolo. I had promised to take them either to Rome or to my village—their choice. They said, “Let’s go to your country for once.” It was a great trip. They saw the village’s medieval church and graveyard, St. Stefano, nestled on the side of the mountain above the village; the scribbles left by Povinelli ancestors on its walls, praying for protection as they left the village; the freezing Alpine creeks; the specially bred cows; the faces that Linda, Rex, and Aiden said looked exactly like mine. They met the mayor, a Povinelli from another clan, and the village genealogist, who wanted me to help fill in and correct the Simonaz family tree. When we got back to Belyuen, my granddaughter Natasha Bigfoot Lewis asked me if I was giving up on Karrabing and going back to my own country. “No,” I said. “Karrabing is my family.”

While I don’t understand all the stakes of these shared and divergent histories, one thing stands out for me. The task is not to avoid the differential sedimentations of value that define how we share affects and histories by digging up some moment in which we were all the same, or similar enough. Nor is the task to ignore the affiliations that may become possible as we come to understand the ramifications of how these shared histories have been buried under a ton of colonial and racial extractions. Nor is the task to abandon the difficulty of allied action for the safety of a purified, autochthonous past. The Inheritance tries to show that even in my case—being a member of a clan with connections to a subnational place stretching back to at least 1494—the point is not to dredge up a precolonial past but to understand it within the ancestral present, its racial and colonial sedimentations, even if you have to bury your own family in the process.

Title video: The Inheritance (Alice Henry Ink, 2021).

{1} Wagait, meaning “beach” in Batjemal (alawa, Emmiyengal), referred to coastal groups around Anson Bay and around the corner to Little Moyle, including Marritjaben, Marriamu, Menthayengal, Emmiyengal, Wadjigiyn, and Kiyuk language groups.

{2} For more on wangga see Allan Marett, Linda Barwick, and Lysbeth Ford, For the Sake of a Song: Wangga Songmen and their Repertoires (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2013).

{3} See Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Labor’s Lot: The Power, History, and Culture of Aboriginal Action (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

{4} For instance, see Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (December 2006): 387–409.

{5} Mark Thompson, The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front, 1915–1919 (New York: Basic Books, 2010).

{6} Sigmund Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. and ed. James Strachey, vol. 14, 1914–1916 (London: The Hogarth Press, 1964), 243–58.

{7} See Karl Marx, “On the Jewish Question,” in The Marx-Engels Reader, 2nd ed., ed. and trans. Robert C. Tucker (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1978), 26–46.

{8} Aristotle, “Poetics,” trans. M. E. Hubbard, in Ancient Literary Criticism, ed. D. A. Russell and M. Winterbottom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972), 108.

{9} Aristotle, 102.

{10} Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958), 190.

{11} Berlant’s work on cruel optimism presupposed and attempted to model a social form that fit the circulatory systems of late liberal capitalism. After all, the worlds that emerged as forms of relation from the dispossession of settler colonialism and the Black Atlantic hardly approach in the same way the philosophical poetics of how things should happen and how they nevertheless do. See Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

{12} For the problematic of fascism from a Karrabing perspective see Elizabeth A. Povinelli and Rex Edmunds, “A Conversation at Bamayak and Mabaluk,” L’Internationale Online, October 2, 2019; and Karrabing, “Australian Babel: A Conversation with Karrabing,” Specimen, October 31, 2017.