Did The Fire Read The Stories It Burnt?*

Chrystel Oloukoï

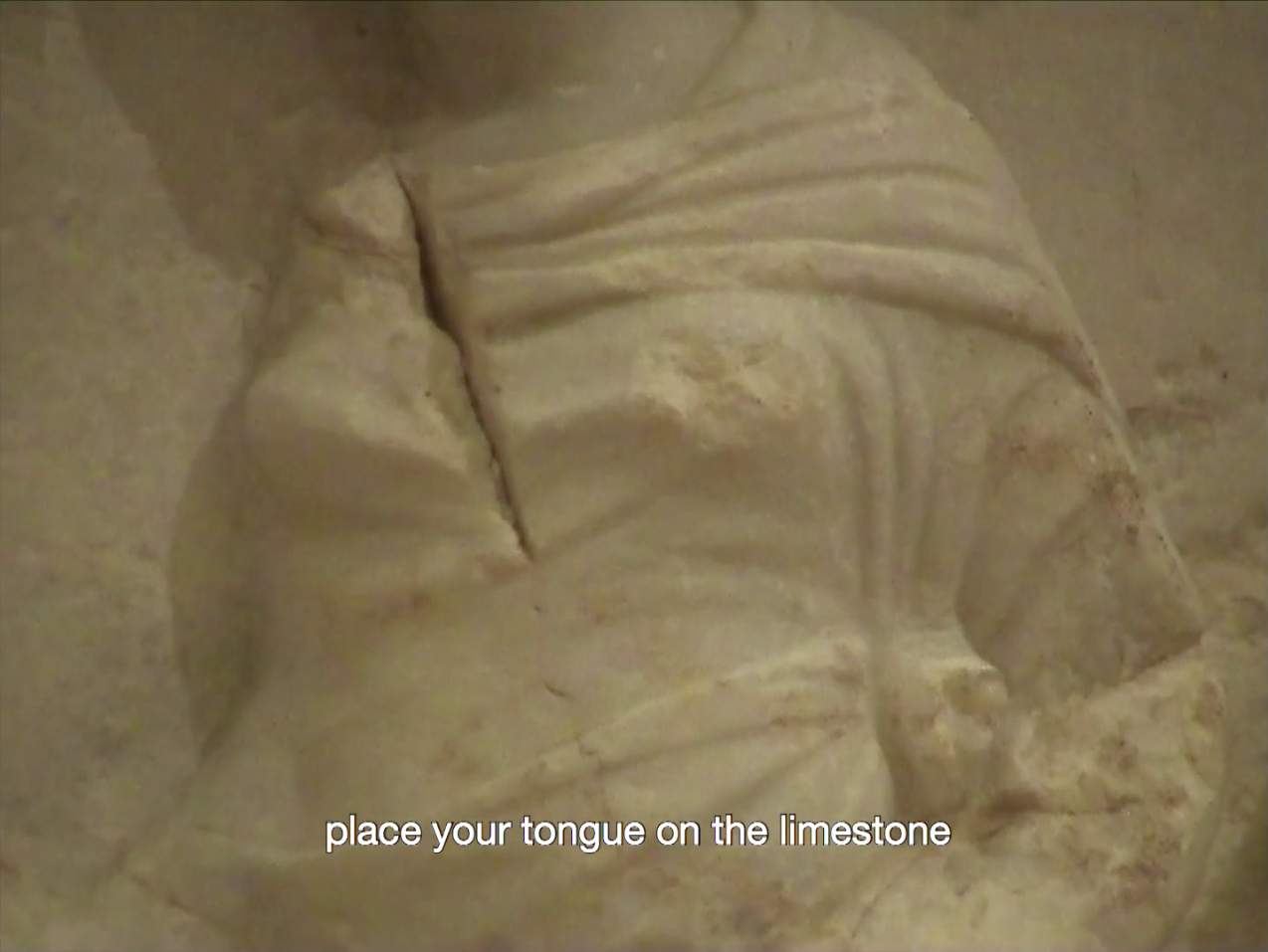

Place your tongue on the limestone

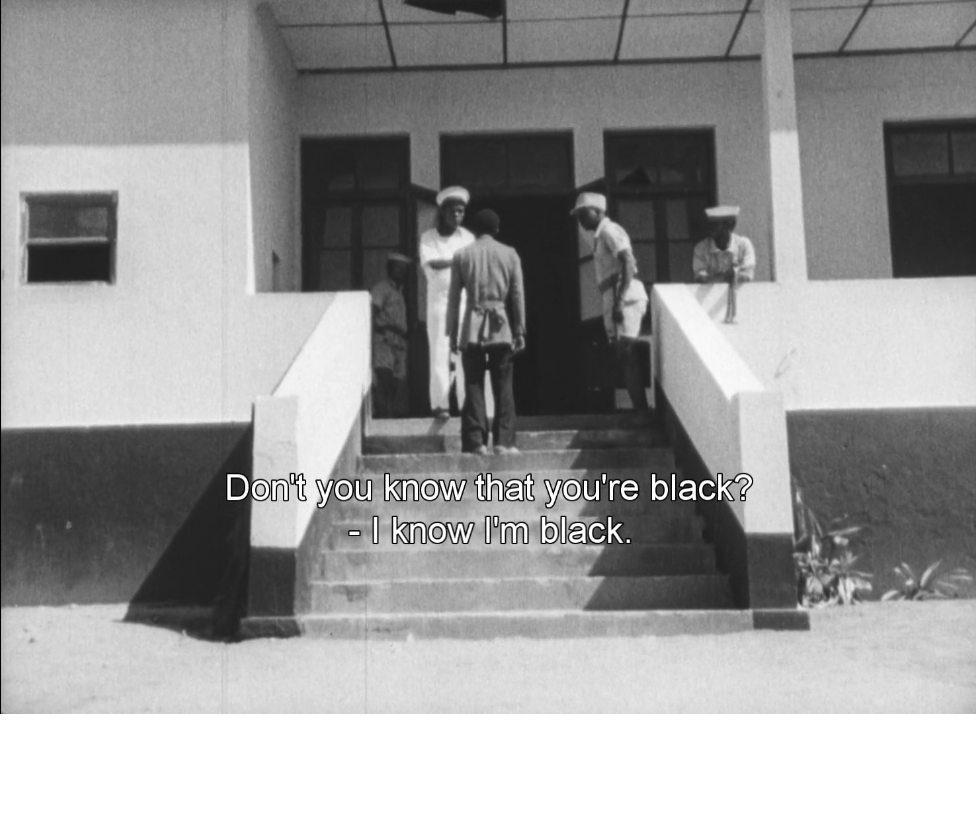

There is a book by French historian Arlette Farge, titled Le goût de l’archive, translated as The Allure of the Archives, but closer in meaning to The Taste of the Archive.{1} Narrating her infatuation with judicial archives and the glimpses they afford into the lives of the urban poor in prerevolutionary eighteenth-century France, the author purports to demystify the archives, insisting on the materiality of the pouches, fabrics, objects, and papers she encounters. Taste here indexes both a sensuous, pleasurable rapport with the archives, and a trained, almost ascetic ability to sit with them. While she quickly moves on to the latter, I wonder about the fetish of the fleshy encounter and the metaphors of consumption that surround it. Why are accounts of archival encounter so pregnant with a romance of touch? Can pleasure in the archives be disentangled from histories of forced contact which the archives both document and resurrect? What does the archive taste like when the downtrodden aren’t on the menu? For those of us for whom the deceptive immediacy of physicality, affect, and all manner of vitalism is no counterspell to colonial ways of knowing, but thoroughly implicated in their afterlives, taste here, the sweet and the acrid, also carries harvests of fire, histories of consuming the images, lifeworlds, and labor power of subjected populations.{2} Nour Ouayda’s 2019 short film Towards the Sun alludes to part of the whiteness that still structures an embodied relation to the archives.{3} “Place your tongue on the limestone,” urges the voiceover. Is it a demand for a kind of intimacy that confirms or exceeds the “dead certainties” of the archives?{4} How does the tongue know? If archives express something not just about deadly histories but about the kinds of relations that emerge from them, then the tongue calls attention both to a desire to consume the other and to a cartography of smoke, wounds, and crevices.

TOWARDS THE SUN (Nour Ouayda, 2019).

TOWARDS THE SUN (Nour Ouayda, 2019).

On April 18, 2021, the University of Cape Town (UCT) African Studies Special Collections Library, which houses numerous ethnographic books, films, and artworks, was engulfed in fire. Students residing in the dorms were evacuated and rendered virtually homeless. Grief over the archives gripped large sections of academic social media, specifically from the North Atlantic, as a citizenry of globally connected archival archipelagoes shared the time spent in these archives, the time they had planned to spend, or the time they now imagined they could have spent. In contrast, a number of Black South Africans on my timeline voiced a different kind of loss—namely, that they didn’t have access to these archives in the first place. And now, in the aftermath of the fire, they never would. Others rejoiced or made a show of their indifference, provoking the ire of scholars, quick to assume that this was some kind of naive nihilism of the uneducated. There was a definitive whiteness—understood as disposition, or what Du Bois calls “ownership of the earth,” rather than as embodiment—in the temporal and spatial command North Atlantic acts of mourning expressed.{5} This contrasts with the more locally embedded forms of grief articulated, for instance, in the wake of the fire at the Cinemateca Brasileira in July 2021.{6}

The Cape Town wildfire originated on Table Mountain, making an erratic way through nonurbanized and urbanized areas, self-sustaining for miles of concrete and tar roads. With hot, dry air and gusty winds, Cape Town was already on fire alert that day, as blazes without the need for continuous fuel were on the rise due to climate change. City officials and the management at Table Mountain National Park swiftly blamed the wildfire on already criminalized vagrants, eking out a living on the mountains.{7} These linkages between the city, the university, and the park are not anodyne. The UCT fire is inextricable from the larger politics of one of the most unequal urban spaces in the world, where monopolistic practices of conservation—from the university archives to the national park—have historically policed, extracted, and segregated access to knowledge, urban space, and the environment for the benefit of mostly cosmopolitan white elites, whether hikers, real estate investors, or academics.

bequest—property given by will, from the Old English “to declare or express in words.”{8}

Situated within a university funded by mining profits and named after John William Jagger, settler benefactor, infamous for his ruthlessness in trade and labor policies, the African Studies Library is a useful example of the imperial networks of subterranean transactions that make archives possible. The African listicles of myriad museums mobilize a language of benevolence and service in tandem with a regime of rights and property, as objects are mysteriously “given,” “purchased,” and “entrusted.” In the stories that museums, archives, and other institutional sites of memory tell about themselves, the romance of the colonies is being written anew, as part of their essential rather than incidental mandate. It is not simply that dispossession here masquerades as gifts, donations, trusts, and endowments. Rather, the gift and the commodity function all too well in the obfuscation of origins because, as coauthorized fictions, foundational to the ideological work of capitalism, they have little meaning outside of dispossession as backdrop and horizon.

As sites of sequestered knowledge, archives extract their value precisely from the primitive accumulations and speculations their enclosures yield. The captivity that haunts archives is not just that of a state of “house arrest,” or of house switching across the basements of various institutional locations.{9} This captivity is also tied to mechanisms of coercion that produce archives in the first place—the systems of restrictions and constraints that regiment their access; the way they function, especially in African Studies, as fields of authorization; the hold they continue to exercise on imaginations.

****

African listicle (from an unnamed museum)

Browse African objects

Artist(s): African

Acquired through purchase and gifts.

Apron (17)

Architectural element

Armlet (5)

Axe (33)

Bark cloth beater

Base for Maternity Figure

Basket or box (21)

Beaded artefacts (58)

Bell (2)

Bellows (4)

Belt (28)

Blanket Bowl (10)

Bow rest

Cache-sex (4)

Canister for matches (5)

Cap (2)

Carpet Censer

Ceramic jewelry molds (18)

Ceremonial chewing stick

Ceremonial fan Chair (5)

Cloth, textile panels (63)

Clyster Comb (14)

Commemorative head (9)

Container (13)

Cup (14)

Cylinders (2)

Dance crest

Divination tray Diviner’s bag (3)

Door locks and slide (5)

Drum (7)

Face or lip plug (7)

Figures (202)

Flute (2)

Fly whisk (4)

Friction and rubbing oracles Funerary post (2)

Gold weight (181)

Gong and striker (4)

Gourd (2)

Granary lock

Hair scratcher

Headpiece (32)

Headrest or neckrest (39)

Healing scroll

Heddle pulley (11)

Helmet Horn and tusks (9)

Hunter’s shirt

Jar and vessels (14)

Jewelry (66)

Kakishi

Kankobele

Knifes and daggers (55)

Ladder

Lamp (2)

Letter opener

Mask (114)

Mortar and pestle (4)

Hymnal: leaf (2) Necklace (3)

Ornament (5)

Paddle (2)

Parts of a scale

Pel ambish

Pipe (17)

Pipe bowl (5)

Pot (6)

Powder flask (3)

Purse (4)

Ritual through Royal Kuba cloth

Sandals and slippers (6)

Scabbard

Scepter (2)

Spoon (5)

Staff (88)

Stool (22)

Sword (17)

Toothbrush

Tunic

Twol (2)

Vessel lid (2)

Wallet

Wall hanging

Whistle (7)

Wig (3)

****

Entomologies

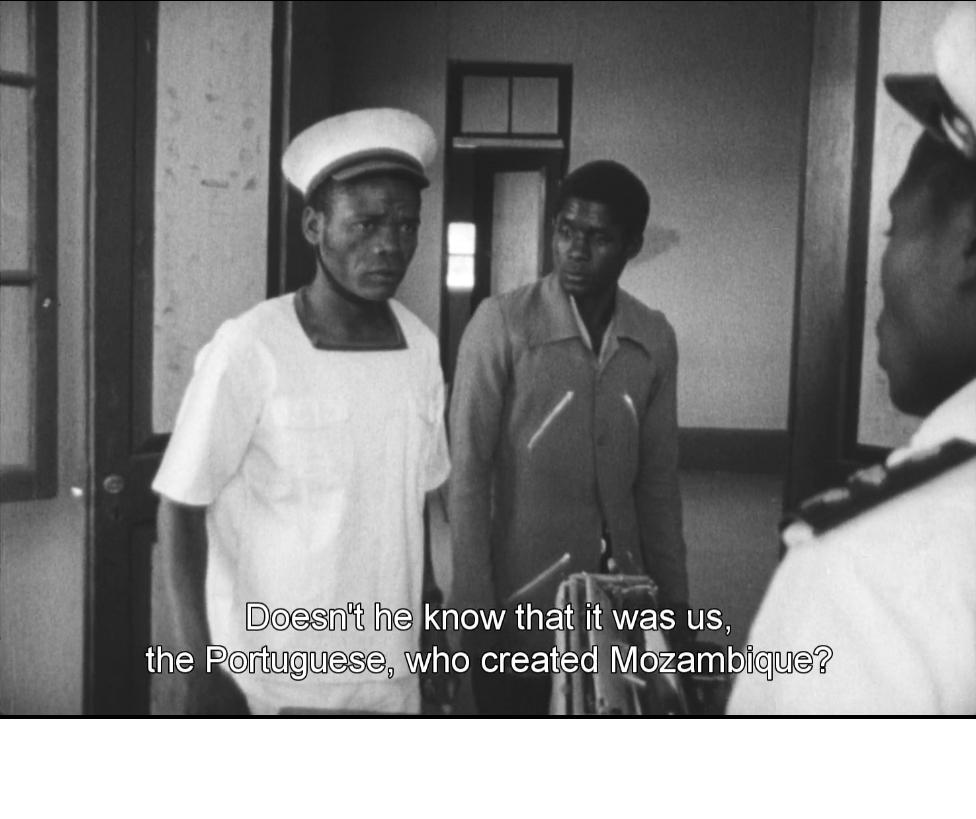

What I hold against you . . . is that you look at us as if we were insects.

—Ousmane Sembène to Jean Rouch{10}

NOMADS OF THE SUN (Henry Brandt, 1954).

NOMADS OF THE SUN (Henry Brandt, 1954).

****

Archive fevers

Nonfiction cinema in recent years has been marked by trafficking in colonial archives, in the form of film, photographs, folders, and documents, often to be interrogated, mined, and repurposed. There is a gold-rush atmosphere to it, the endless mining for the right encounter in the archives, the arresting gaze of the past, the haunting gesture that can provide enough of a supplement of soul. Revisionist orientations are embedded in our socialization to archives, our fascination with records, whether written with ink, light, or sound. After all, the audiovisual archive fits squarely within a Western episteme of capture that constructs itself against the ephemerality of speech, its porosity to change, its decay.{11} Considering how the documented threaten the undocumented, the truism that the latter is always fragmentary, messy, or even flawed holds little weight.

Most know or come to know in the archival encounter that, to quote Anjali Arondekar, the “debts of the colonial state [cannot be] paid off through its archival debris,” that they far exceed the colonial arithmetics of documentation and its theater of objective accounting.{12} Yet documentation produces its own effects, insistences, and structures of address. Declarations of existence, records of harm. And yet still, the use of archives, specifically in Black continental and diasporic nonfiction cinema, can gesture at the expanse of a grief the archives cannot hold. It is a kind of nonfiction cinema that asks questions of the faces in the visual archive, probing the edges of an impossible dialogue, as in Onyeka Igwe’s haunting short about the Colonial Film Unit’s archives of Black dances, Specialised Technique (2018):

Is this OK? Did you want your whole body in the shot? Is that why you never open your eyes? Is it why I look down? Or away? What happened when you looked down the lens? Or did they tell you not to? Do you not want me to see your face? What do I want to focus on? Your ankles as you jump? what you have in your hand? the shape you make with your arms? just your white cloth? Do you wish it was a tighter shot? How do you want me to frame the shot? What do I want in close-up? Should I move? Further back? To one side? In the middle? Am I OK?

Found footage takes on a surplus of meaning in relation to Black film. The histories of dispossession and visual extraversion we inherit mean that a disproportionate amount of the images we have of ourselves are de facto found footage. Repurposing then becomes central to acts of mourning and care through film. The most pressing question remains, How does one not reproduce the grammars of subjection in such critical reclamations, defamations, or even fabulations?{13}

SPECIALISED TECHNIQUE (Onyeka Igwe, 2018).

Such grammars include the regimes of rights and property in which these images are held. There is a materiality to archival returns and the web of relations and transactions they mobilize. Citation is a form of currency in a saturated marketplace of images, as artists often have to pay exorbitant fees even as cases for fair use could be made, meanwhile giving value to the images they repurpose. We could question the point of resurrection, as if these buried images weren’t also the texture of our present, as if their recirculation produced rather than confirmed the inherited, enduring visual landscape that gives them meaning. In Igwe’s Specialised Technique, a dancing lower body in a leather skirt becomes the living and textured screen onto which black-and-white colonial footage of Black dance is projected. The kindred motion between the archived and the contemporary Black body speaks to the uncanny repetitions embedded in pasts which are yet to pass. As the spoils of slavery and colonialism continue to generate profit for the perpetrators, while those condemned to live in their afterlives pay for the congealed spectacles of their own subjection, what in these images makes such transactions feel not only possible but necessary, imbued with urgency?

The archival form itself is also central to the grammar of subjection: inscription as destination, trust, and mandate. What to think then of the ever-increasing incorporation of sets of disparate objects and collective practices under the hegemonizing rubric of the archive? Of the feverish enthusiasm with which families without heirlooms are enjoined to collect stories? Collecting, as a practice, rehearses colonial horizons of posterity and enclosure, along with the latter’s speculative modes of valuation. Archives have always constituted a diverse array of objects—artifacts, films, daguerreotypes, documents, records, even remains did not escape such captivity—but as neoliberal logics continue to invite their proliferations, our understandings of relation and generation become wedded to them. The archival form is inextricable from mechanisms of ordering and legibility. For the dispossessed, it is also entangled with all kinds of proximities to death and anticipations of genocide. A family album, a song, or communal memories get called an archive; those who constitute it remain, as ever, in a state of proximity to premature death.

****

Trail of evidence

Ruy Guerra’s Mueda, Memória e Massacre (1979) centers on a key event of Mozambican anticolonial memory. Facing demands for higher pay and more freedoms, Portuguese authorities proposed a meeting with leaders of the opposition in the town of Mueda on June 16, 1960, only to arrest them, and kill protestors. Six hundred people died. The film is less about the events themselves than the very act of remembrance, that is, the popular stage plays reenacting the event every year on the day of the massacre. I imagine such plays to be full of discrepancies, slippages in meaning and practice, imbued with the aliveness of popular memory. Yet reenactments are full of discipline as well.

From the outset of the film, we hear what sounds like the discordant unity of recitations in a children’s history class. The Portuguese arrived in 1498. They named the island and later the mainland country “Mozambique,” based off the local ruler, sultan Ali Musa Mbiki. The first inhabitants were the Khoisans who fled to the Kalahari Desert, followed by the Hottentots, then the Bantus. The popular stage plays are but one piece of a larger structure of remembrance in which the nation represents itself, from schools to museums, place names to public holidays. One of the protagonists in the film insists on “good posture,” suggesting the imagined audience for such representations extends beyond the nation’s borders. This film will be shown in Europe and the rest of the world. “Posture” here becomes a form of narrative composition and paginal arrangement, Europe standing as both the accused and the imagined audience. As structures of address confirm the world order that made the massacre possible in the first place, these kinds of reenactments seem to borrow from the texture of trauma, grief, and vindication and from the executioner’s own narcissistic pleasure at the same time.

Address here also partakes of an evidentiary regime of truth, in which the administration of evidence—a regime in which we seem locked by virtue of the nature of archives—produces its own kinds of disciplines and carcerality. That is, perhaps, what keeps reenactments from turning into rehearsals. How much evidence is enough evidence? Who is the jury, if not the executioner? Why do we seek freedom there?

****

Harvesting fires

What if the fires that haunt the archive were a kind of remembering?

In the past four years, Benin City in Nigeria experienced no less than ten large-scale fires, and countless smaller ones. The origin is often accidental, caused by the various ramifications of an inadequate, unstable, and irregular power supply, from sudden electrical surges to fires and explosions involving oil tankers, generators, and cooking fuels such as kerosene, gas, and charcoal. The effects of the fires themselves are magnified by belated responses from firefighters, often nowhere in sight or lacking enough water to put the fire out. On the night of August 12, 2019, Uwelu, the biggest spare-parts market in Edo State, went up in flames, devastating more than ninety shops. As apprentices to masters or debtors to various predatory moneylenders, most of the vendors did not own the shops. Still, even amid gutted structures, exposed walls, and landscapes of ash, commercial activity must go on. Until the next fire.

Why do I mention the harvests of fire in Benin City? Aside from migration stories, the other context in which those outside the country are most likely to hear news from Benin is the case for the repatriation of its bronzes and artifacts looted during the 1897 British punitive expedition and subsequent burning of the city.{14} Benin hasn’t stopped burning since. Fire, as an inheritance, points to “the manner in which the catastrophic is ongoing, yet still tied to an ‘original’ detonation of sorts,” the linkages and intimacies between these temporally distant fires.{15} To what extent do they put pressure on colonial notions of time, causality, and value? How are archives recast in the shadow of fire?

Fires of different sorts make possible and sustain the lives of museums and archives. In her short film The Heat Treatment (2021), Bianca Hlywa documents the heating chambers and other antilife processes through which museums such as Oslo’s Teknisk Museum wage wars against moths, beetles, and silverfish. Conservation workers bear the brunt of it, from the nerve damage induced by the past use of heavy pesticides to the fainting spells and dizziness associated with working in rooms where oxygen levels must be kept low to avoid oxidizing. From the way objects are acquired to the protocols through which they are maintained, the great Western enterprise of preservation is a pale mirror to its grand enterprise of destruction and to the ruins that animate its conservationist energies. As such, the ability to look at the aftermath of fire as “art” or “archive” is the routine ideological work of museal and archival institutions and their technologies of abstraction and revision.

What kind of living does a harvest of fire afford? The aftermath of fire is often considered a tabula rasa, starting anew out of nothing. But the truth of fires is that they do not merely bring a ground zero; they also threaten to deplete the potential for futures. The tragedies they bring cannot be circumscribed by the event itself, nor even by the reduced life spans left in its wake. “Why didn’t you also warn / Our eyes would forever be smokey?” asks the poet Jack Mapanje.{16} Living in the shadow of a harvest of fire also means living in a state of enforced, structural amnesia. As British armies destroyed peoples, they also filled museums and private collections. Somewhere in New York, someone knows everything there is to know—in the colonial sense of knowing—about the Benin Bronzes, as history gets removed from Nigerian school curriculums, adding to the burden of already structurally underfunded cultural institutions. When objects do return, they return precisely as objects, as collections. No amount of posturing will hide the fact that, the way the board is set, this is a zero-sum game.

****

On belonging to history

“The important thing is making generations. They can burn the papers but they can’t burn conscious, Ursa. And that’s what makes the evidence. And that’s what makes the verdict.”

“Procreation. That could also be a slave-breeder’s way of thinking.”

“But it’s not.”

—Gayl Jones, Corregidora{17}

On the evening of July 29, 2021, the Cinemateca Brasileira, which housed more than 250,000 Brazilian films and countless related documents, also faced its own kinds of fire. The workers of the Cinemateca, long alerted to the risks, speak of a “crime foretold” in their statement of July 30.{18} They situate the fire in a chain of defunding-related catastrophes, the fire being the fifth in the institution’s history, alongside a flood in February 2020. The tragedy of the Cinemateca speaks to a larger moment in which archives are fetishized but archival labor is devalued. It also lays bare how imperatives of preservation, the mandate to be suspended in a belonging to history in all its brutality, can only be made of the dispossessed, not of those in power.

While Tamara Lanier is told by Harvard University that the images of her ancestors “belong to history,” thus remaining entrusted to the very institution that produced them for racist purposes and left them sitting, unattended, in a drawer for decades, archives are destroyed every day by the powerful.{19} Bolsanaro’s far-right government defunded the Cinemateca and, on August 8, 2020, fired all technical staff without paying salaries or severance packages. The fire of July 29 was but a visible manifestation of a long process of combustion. While scenes of destruction with their quantifiable losses harness our imaginations, the Cinemateca Brasileira, in ways similar to Benin City, confronts us with the forms of slow death that make such spectacles possible in the first place, from the institutional abandonment affecting routine operations of preservation to the now reduced life span of the materials that survived, the nitrate and acetate film stocks having been exposed to fire.

The aftermath of the UCT fire—namely, the incommensurability between the acts of mourning of some and the rejoicing of others—dramatizes a subaltern, incendiary refusal to belong to history. Declarations of disinterest or antagonism toward the kinds of archives held in places such as UCT elicit patronizing and horror. While fantasies of destruction transgress the sacrality of the archive, opening up space for necessary reorientations, they nonetheless tend to reproduce its fetish, through the conceit of a sovereign gesture that can burn the present through its papers. In Jones’s Corregidora, the burning of the slavery papers only compels the bodies of the Corregidora women to keep bearing witness through a repressed but no less cruel embodied storytelling. King Lobengula’s Bulawayo—in contemporary Zimbabwe—burned twice, first as ritual custom, since Ndebele royal towns were not meant to be permanent, and second as anticolonial defiance.{20} On its ruins, white settlers built a third Bulawayo. The harvests of fire inherited by places like Benin City suggest that destruction and conservation are not antithetical, but often tethered.

“Regenerative arsons” destroy the relations that suture archival logics, exceeding the destruction of mere archival objects.{21} In his ongoing film project Lucid Decapitation (2021–), on the toppling of a Columbus statue by Indigenous protestors in Minnesota, Karthik Pandian suggests we look at destruction as a form of carework, thus inviting seemingly conflicting temporal orientations. Destruction takes us away from the injunction to permanence, but care extends, and potentially challenges, the no less colonial temporality and sovereignty of the event. Through acts of ritual, which include the making of the film but also performances that cannot be repeated, Pandian attempts to proliferate the energies, solidarities, and modes of relation unleashed by the event, more than to preserve a codified memory of the event itself.

****

Who will start another fire?

Didn’t you say we should trace

your footprints unmindful of

quagmires, thickets and rivers

until we reached your nsolo tree?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Why does your mind boggle:

Who will offer another gourd

Who will force another step

To hide our shame?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

You’ve chanted yourselves hoarse

Chilembwe is gone in your dust

Stop lingering then:

Who will start another fire?

—Jack Mapanje, “Before Chilembwe Tree”{22}

HALIMUHFACK (Christopher Harris, 2016).

HALIMUHFACK (Christopher Harris, 2016).

Zora Neale Hurston’s work, in particular her songs, clears a space in which the formidable task to “imagine ourselves unimagined” seems possible.{23} In Christopher Harris’s Halimuhfack (2016), an actress in a lush dark-green dress, wooden-beads necklace, red hat, and black leather gloves lip-synchs to recordings of Hurston singing and narrating her research process. Behind her, a screen displays an ethnographic film of Maasai people dancing and returning the camera’s gaze. The voice of Hurston never fully synchs with the lips of the actress, emphasizing the multilayered gaps between the object and technologies of capture and representation. A student of Franz Boas, Hurston herself already practiced a kind of “sonic infidelity” which refused ethnographic illusions of faithful, unmediated reproduction.{24} She approached African American and Caribbean folk songs and stories through embodied practice, through learning and improvisation. The distorted and looped voice of Hurston in Halimuhfack ends up producing its own kind of uncanny musicality and records of discordance, emphasizing both the violence of capture and the ways in which what matters actually eludes it.

How does one cultivate a relation of irreverence toward the archive and the mandate to record everything? Chart paths away from its states of captivity? For those of us sick with archive fatigue, what forms of memory and accountability not grounded in its order of truth and cold litanies are already being practiced?

****

Acknowledgments: I’m thankful for Onyeka Igwe’s course “Archives in Non-Fiction Cinema” at Open City Docs in 2021, which was a crucial space of learning, exchange, and reflection.

* Title borrowed from Denise Ferreira da Silva and Jota Mombaça’s 2021 sonic performance opera infinita, specifically “chapter 0: has the fire read the stories it burnt?,” which calls attention to the variegated qualities of flammable materials, and how they translate into different paces and rhythms. The piece thinks with and beyond the devastation of fire to probe its generative potentials, through sound decomposition, distortion, and fragmentation.

Title video: Towards the Sun (Nour Ouayda, 2019).

{1} Arlette Farge, The Allure of the Archives, trans. Thomas Scott-Railton (1989; repr., New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015).

{2} See Axelle Karera’s critique of how new materialisms deploy immediacy as a way to bypass social and/or ontological antagonisms, as well as how abstracted notions of the “human” or “life” reproduce an ethics grounded in antiblackness. Axelle Karera, “Blackness and the Pitfalls of Anthropocene Ethics,” Critical Philosophy of Race 7, no. 1 (2019): 32–56. Additionally, William Mazzarella’s analysis of the “mana moment” from 1870 to 1920 in Euro-American social thought, especially anthropology, illustrates not only earlier iterations of the kinds of arguments made by new materialisms, but also their entanglement with colonial ways of knowing. See William Mazzarella, The Mana of Mass Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017). Lastly, on “sweetness” see Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York: Penguin, 1986).

{3} While I mostly focus on institutional archives—in their entanglement with empire—collecting, as a practice, engages the dispositions and materiality of a regime of rights and property in ways that even subaltern and alternative archives do not completely escape. Indeed, where does the desire to collect or to conserve come from? How are we socialized into it? What does collecting, as a habit, do to the objects thus gathered?

{4} Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (June 2008): 9.

{5} W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Souls of White Folk,” in Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920), 30.

{6} This also translates in the forms of activism elicited by these tragedies. In the case of UCT, there was a call, emanating from a scholar in Copenhagen, for global academics to send scans or images they might have taken of documents from the Special Collections Library. “UCT African Studies Library Special Collections Recovery,” Google Forms survey, accessed July 27, 2022. In the case of the Cinemateca, on the other hand, workers sent out a call to address the root causes of institutional neglect that led to the fire. “Statement from the Cinemateca Brasileira workers regarding the fire at the Vila Leopoldina site,” fiaf (International Federation of Film Archives), accessed July 27, 2022.

{7} See, for instance, Tom Head, “Devastating Cape Town Fire ‘caused by a vagrant’—SANParks,” The South African, April 18, 2021.

{8} Black’s Law Dictionary, 8th ed. (2004), s.v. “bequest.”

{9} On “house arrest” see Jacques Derrida, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” Diacritics 25, no. 2 (Summer 1995): 10.

{10} Albert Cervoni, “A Historic Confrontation in 1965 between Jean Rouch and Ousmane Sembène: ‘You Look at Us as If We Were Insects,’” in Ousmane Sembène: Interviews, ed. Annett Busch and Max Annas (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), 4.

{11} Capture or fixation as a condition of possibility for apprehending the world is a key paradigm in numerous texts of Western philosophy, often articulated in a binary opposition between speech and writing, which Jacques Derrida later complicates. See, for instance, how Paul Ricoeur rehearses Saussure when he states, “In living speech, the instance of discourse has the character of a fleeting event. The event appears and disappears. This is why there is a problem of fixation, of inscription. . . . Inscription, in spite of its perils, is discourse’s destination.” Paul Ricoeur, “The Model of the Text,” in Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences: Essays on Language, Action and Interpretation, ed. and trans. John B. Thompson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 160–61.

{12} Anjali Arondekar, “Without a Trace: Sexuality and the Colonial Archive,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 14, no. 1/2 (January/April 2005): 27.

{13} Or, as Saidiya Hartman asks, “How does one revisit the scene of subjection without replicating the grammar of violence?” Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” 4.

{14} See Peju Layiwola, “Making Meaning from a Fragmented Past: 1897 and the Creative Process,” Open Arts Journal, no. 3 (Summer 2014): 87–96.

{15} Bedour Alagraa, “The Interminable Catastrophe,” Offshoot Journal, March 1, 2021.

{16} Jack Mapanje, “Man On Chiuta’s Ascension,” in Of Chameleons and Gods: Poems (Oxford: Heinemann, 1991), 9.

{17} Gayl Jones, Corregidora (Boston: Beacon Press, 1975), 22.

{18} “Statement from the Cinemateca.”

{19} “Those images belong to history” are the words of Lawrence S. Bacow, president of Harvard. Quoted in Jarrett Drake, “Blood at the Root,” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies 8, no. 1 (2021): 6.

{20} See Panashe Chigumadzi, “Ukutshisa: Setting Fire to the Future,” Future Library Booklet, Tsitsi Dangaremba 2021: 7–17. Available online, accessed July 27, 2022.

{21} On “regenerative arson” see Jasmina Price, “Fire Blossoms,” ed. Oona Mosna, special dossier, Three Fold, no. 7 (Summer 2022).

{22} Mapanje, Of Chameleons and Gods, 18, 19.

{23} From Lucille Clifton’s poem “here yet be dragons”: “who / among us can imagine ourselves / unimagined? . . .” Lucille Clifton, The Book of Light (Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 1993), 31.

{24} Roshanak Kheshti, Modernity’s Ear: Listening to Race and Gender in World Music (New York: NYU Press, 2015), 125–42.