Possibility Made Real

Lana Lin

“Reality often feels unmoored, confusing, unstorified, especially when experienced in crisis.”

—Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow {1}

****

This essay is derived from a lecture I gave in 2019, in which I discuss a 2018 film that was a response to my cancer diagnosis of eight years prior, and which took its inspiration from Audre Lorde’s reckoning with her own cancer diagnosis over four decades ago. I was diagnosed with breast cancer during my last year of doctoral coursework and seven weeks into a course co-taught by Jonathan Kahana. After that subsequently strange seminar, the next and last time I saw Jonathan was at a symposium where I delivered this lecture. I was in remission and he was the one with active cancer. Now in 2021, in the midst of a pandemic that has called many to confront mortality with the urgency that compels cancer patients, I contemplate the trajectory of these events. I might plot them on a timeline, as I have here, building connective tissue that attempts to make sense of them. But I am unsettled by the question of what is left out in the effort to narrativize. How else might sense be made of random events that resist explanation? Is coherence the best and only aim for how we frame and reflect upon experience?

If story wants to give meaning and order to the chaos around us, illness and death work to confound that urge. And yet facing death also seems to demand testimony. In the years since I first collated the following words, I am dogged by unresolved questions around what we gain from story as well as what we lose by way of its restrictions and occlusions. Even as I recognize the psychic release that accompanies narrativization, a more capacious vision that can be glimpsed at the ragged edges of story and radical accounts that go beyond it can afford us possibilities of which we have not yet dreamed.

The Cancer Journals Revisited (Lana Lin, 2018) is a poetic rumination that seeks to perform a close reading of Black feminist poet Audre Lorde’s 1980 memoir of her breast cancer experience through readings by twenty-seven participants. Between 2016 and 2018, I invited people from a range of backgrounds, ages, ethnicities, and sexual and gender identities to read aloud excerpts from The Cancer Journals, which could also rightly be called a manifesto. Each reader reflects upon the meaning of the recited passage for them personally and in relation to our contemporary moment. Each person speaks individually, yet in a collective voice. The artists, activists, writers, health care advocates, and current and former patients produce an oration for the screen and convey the arc of the book over the course of ninety-eight minutes. Extending from a single authorial voice, the readers respond to the text in distinctly personal ways, while their collective action of speech amounts to a political act. The readers add a vocal and embodied dimension to a text that resonates today at an almost frightening pitch.

Adrienne Rich, one of Lorde’s closest comrades, urged women to “re-vision” old texts and worn assumptions of a patriarchal order for the sake of their own survival.{2} Feminist re-visioning performs for Rich the work of self-knowledge. Lorde locates this mode of self-examination in poetry. I like to think that TCJR follows suit with its critical self-inquiry. I re-vision not to bring to light the feminist potential of a male dominated canon, but to reignite a feminist classic in light of the present moment, one that espoused intersectional care of the self and care for others well before such ideas had become widely popularized. The continued relevance of The Cancer Journals in the nearly four decades since its original publication indicates not so much stasis as a Sisyphean return. The gains in civil rights that had been attained between 1980 and 2017 have since been rolled back. If HIV-AIDS has become a managed chronic illness for privileged North Americans and Europeans, it remains a scourge among the urban poor in both the Global North and South, most devastatingly in Sub-Saharan Africa. While breast reconstruction is customarily covered by health insurance, and reconstruction has become so technologically perfected as to grace such beauty icons as Angelina Jolie, health insurance remains a privilege of the economically advantaged, and African American women die of breast cancer at the highest rates of any ethnic group in the US. When Lorde writes of Black boys being routinely murdered on the street by police officers, likely referring to Clifford Glover, she could as easily be speaking of Tamir Rice or Michael Brown or many others from a list that could go on far too long.

TCJR is motivated by the persistence of what Juhasz and Lebow call “unstorified” crisis. Who but a poet, a staunchly political, activist poet, could address the pervasive, multi-layered crisis of cancer in our times, and the ways it penetrates every level of social life and death, and how it does so unequally? In making TCJR I was not driven to tell my story of cancer, nor expressly to collect other individuals’ stories about their cancer experiences, although to some degree the film does summon such stories. My primary impetus for making the film was to ask what this text, which uses cancer as a way of investigating the deep wounds of racism, sexism, ableism, and environmental degradation, means for us today. And to call into question who this “us” is and can be, to call attention to the formation of an “us” in its making. Who are “we”; who can “we” claim to be?

TCJR aims for a mode of interaction that finds precedence in the vocalized reiteration of primary texts in Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub’s rigorous, somewhat alienating films. In describing Straub and Huillet’s work, critic Barton Byg writes:

Each film respects the form of the text it presents, drawing it into sharp clarity by treating it not as a transparent technical element, as material for a story, but as a text, a material document. . . . The films record their own confrontations with the text, the challenge made to the text by its setting, for instance, in a contemporary landscape. The films document the interaction between the original form and content of the text and the form of the film in which the text is cited or recited.{3}

My treatment of The Cancer Journals echoes Straub and Huillet’s process. In answer to the Lorde Estate, which forbade an adaptation of The Cancer Journals, I underscored my desire to honor and serve the text as a material document, and expressly not as material for a story. Although TCJR likely sits somewhere between typical audience expectations of an experimental and documentary film, it is a documentary to the extent that, as in Straub and Huillet, it documents my confrontation with the text and the challenge of bringing it to a contemporary setting. TCJR’s form is modeled on Lorde’s hybrid memoir/manifesto, which blends poetry and politics. It highlights the interaction between Lorde’s original and my re-visioning of it, with attention to the form of the primary document and my own interpretation. This poetic, performative, discursive, and critical encounter provides the central motor of the film, rather than any of the individual component stories (mine included).

Excerpt from THE CANCER JOURNALS REVISITED, Lana Lin (2018).

In Lorde’s typewritten drafts of The Cancer Journals, which are held in the Spelman College archive, we do not so much follow the story of her acceptance of mortality as we witness a temporal collision. On a page that appears in the folder “BC: A Black Lesbian Feminist Experience. Part III – Power vs. Prosthesis,” the third person “she” is replaced by the first person “I.” The reader can readily perceive evidence of Lorde’s edits through tense ballpoint pen scribbles and angry black pencil, redacting key words. Lorde initially writes that every woman with a potential cancer diagnosis comes face-to-face with her own death, but scratches this out and implicates herself with “I has already faced my own death” (italics mine).{4} Lorde’s retrospection is embedded in the present moment that bears the mark of the past. The conjunction of present and past in the manuscript draft documents the turmoil that she—or shall I say I?—face(s) in the encounter with mortality. In these edits Lorde insists upon making the personal political and the political personal. She makes a public claim and takes responsibility for her life, her feared death, and the strength it takes her to survive both.

In TCJR, Lorde’s material, and the rereading of that material, function in a manner similar to Lorde’s palimpsest, where the traces of an original thought or word remain beneath the reconsiderations and discoveries. As the film’s director, I never asked the participants to tell me the stories of how cancer touched their lives. Instead, I asked them what reading the selected passages meant to them. Often they chose to interpret the text in relation to their own experience, which is not equivalent to telling me their own story, but homes in on the reverberations of Lorde’s words within their own situations. Rather than simply telling their stories, or telling a simple story, the contemporary readers in TCJR enact a confrontation with the legacy of Lorde’s words.

Figure 1. Still from THE CANCER JOURNALS REVISITED, Lana Lin (2018).

Figure 1. Still from THE CANCER JOURNALS REVISITED, Lana Lin (2018).

The oscillation between community and the individual, and their ultimate mutual interdependence, can be discerned in Lorde’s draft manuscript. Lorde was committed to celebrating her community of fellow survivors (and I don’t mean only cancer survivors) those who, as she puts it, “were never meant to survive.”{5} Yet she was equally committed to preserving her varied self-identities—as a poet, a mother, a lesbian, a Black woman, a warrior. Her embrace of community is strategic and political. As an individual, she is intent on recognizing the value of Black and brown bodies, poor bodies, disabled bodies, migrant and immigrant bodies, gender non-conforming bodies, and this recognition requires a communal effort.

TCJR mirrors this idea that the self is both individual and collective, proposing that selfhood might be considered plural, and that the prospect of survival depends upon care for that fragile plurality. In TCJR each of the readers save two appear on camera alone. Their voices accumulate into a collectivity while preserving their individuality. Additionally, the readers function as stand-ins for me, a means for my self to be pluralized, to be both individual and personal, as well as collectively political. While my voice is not audible in the film, it appears as text throughout, and I understand and believe it is felt as the guiding force behind the film in tandem with Lorde’s. My singular and plural identities act as a holding environment, a container for the words and affects that have been convened on the screen and in the screening room.

The building of a plural self, of the first person plural, may be a function of pronouns, the fluctuation of the “I” and the “we” in which both are preserved and interdependent.{6} This community of individuals comes into being through the power of direct address. The Cancer Journals originated as a lecture, “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” which was given, as is typical of the lecture format, in the first person, making generous use of the second person in addressing its audience. Lorde’s “you” reaches out from its initial delivery in a room where nervous laughter followed her introduction as a “Black, radical, militant, lesbian feminist” to a future that she reels in to heed her call. Insisting that her labor as a Black woman warrior poet is integral to her identity, she turns her self-knowledge into a provocation unflinchingly aimed squarely at her listeners: “I am . . . doing my work, come to ask you, are you doing yours?”{7}

TCJR answers Lorde’s call to do my work, to assemble my fragmentary identities and to put them together towards some kind of collective action, to dare to reveal my endangered selves for the prospect of making real a future in which the very idea of community could be possible. The film replicates Lorde’s direct address with the reader/participants speaking directly to the camera/audience. The second-person pronoun “you” hails the viewer/listener and produces a community that reaches beyond the onscreen readers to those for whom The Cancer Journals is read. In her study on the power and function of pronouns in filmed interviews, Paige Sarlin observes, “The deployment of the generic ‘you’ in a filmed interview marks the possibility to refuse being singular, reducing oneself to ‘one.’ It can invite auditors to imagine a shared difference.”{8} TCJR’s “I” hails “you,” forming a “we” who may have in common only that they have borne witness to a shared moment of listening and viewing.

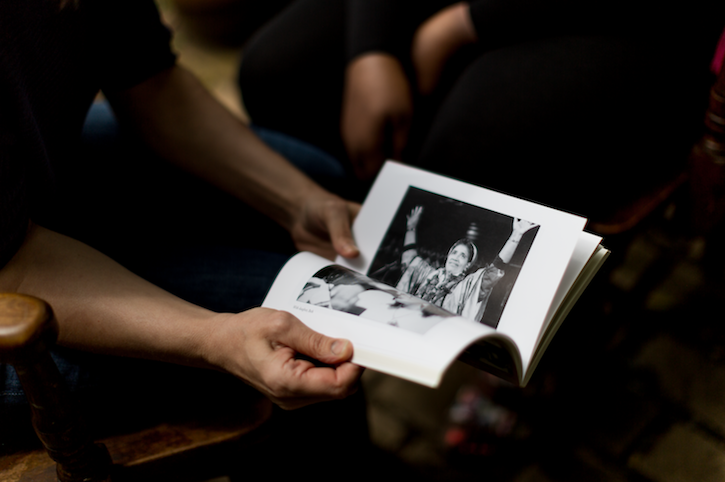

Figure 2. Production still. THE CANCER JOURNALS REVISITED, Lana Lin (2018). Courtesy Nan Zhang.

Figure 2. Production still. THE CANCER JOURNALS REVISITED, Lana Lin (2018). Courtesy Nan Zhang.

TCJR’s participants, whose readings form linkages to a temporary community, share above all not their diagnosis or even a relationship to cancer, but their experience of having recited Lorde’s text. Many of TCJR’s readers resort to the second person at the moment they are at their most vulnerable. Michelle Handelman shifts to “you” in describing the dehumanization of cancer treatment: “I got a geiger counter to check how radioactive I was and I was off the charts. And that otherizing, that separation of you from the rest of the world, is very hard to come back from.” As a kind of self-defense, “you” defuses the loneliness of an “I” that is excluded from the community of human contact. Maria-Elena Grant reflects on the alienation that cancer and its treatment cause, a self-alienation and alienation from others. When her dog can no longer recognize her because chemotherapy altered her scent, she laments: “even my doggy doesn’t love me anymore, like how you have to get to know yourself again and the hard work in that.” The hazardous path toward self-knowledge is more safely navigated with the protection of the second person. Lama Bazzi likewise deflects her pain by shielding her bare first person under cover of “you”: “I’m going to live, but then once you’ve lived, there is also, how are you going to live and who do you really want to be when you are not defined by cancer and treatment and follow-ups and care.” When she recalls her family’s fear of losing her, she turns to the second person exactly when she wants to point out how she is not an isolated individual: “that makes you so vulnerable because it’s not just me.” Her connections to a community are what make her vulnerable, and not just her, but those of us whom she is addressing.

Perhaps because she is a writer herself, Porochista Khakpour keenly identifies Lorde’s deliberate adoption of “you” as a kind of hinge between the present and future, which may also stem from the ways in which she can hold both vulnerability and strength at once:

She has this incredible vulnerability that is just the twin of the strong and the empowered. But there is also a way in which she’s very aware of that “you,” the audience that she’s talking to in the future, so there’s a way that you feel quite shaken by its personalness, if that’s a, that’s a wonky word, but you feel that it’s actually very directly talking to you.

TCJR carries on a conversation with a text that emanates from the past, but which is itself in dialogue with its own past and future. This places TCJR in a queer temporal position, as in a non-normative time that works against conventional linear chronology. As a speech act, TCJR strives to render its plural subject, my and other selves, legible only in so far as viewers/listeners recognize the limits of that legibility. I/we/they/it—this multiple pronoun-ed object takes pride in and maintains its right to opacity.

In her analysis of human rights speech acts and the role they play within participatory documentary aesthetics, Pooja Rangan levies a nuanced critique of the humanitarian impulse in documentary that seeks to bring a community of “others” into the fold of humanity, yet she detects a trace, a potential within the very structure of the interpellative hail. In giving the “other” the “gift of documentary,” she notes, the interpellative hail may be returned as a counter-hail that “interpellate(s) humans as that which is excluded from the definition of human, that is, as not yet normatively human.”{9} I hear Lorde’s piercing challenge to do our own work as such a counter-hail. For Lorde and for me, and I venture for many of TCJR’s participants, a repudiation of a humanity that imposes entry requirements for humanity dates prior to a cancer diagnosis, stemming from the lived experience of non-normative gender and race. From the perspective of the film director/editor, the voices in TCJR reject a humanity that is apportioned only to those who meet a criterion for humane treatment, not because cancer has dehumanized them, nor because the medical system has been dehumanizing, but because contracting cancer underscores the inhumanity of a humanity designed on the basis of inclusion and exclusion. The “unstorified” crisis of the “not yet normatively human.” Such lives bear little resemblance to a story well told.

Compulsion toward storytelling plays a leading role in another genre besides documentary or even dramatic film: the illness narrative. Since Arthur Frank wrote his influential book The Wounded Storyteller, much attention has been paid to the need that besets many patients to make sense of illness.{10} It is a human quality to strive to construct some meaning out of suffering, although it is possible to unstorify crisis through unheroic chronicles, such as The Cancer Journals, and experimental non-linear narratives, such as queer theorist and poet Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s A Dialogue on Love, which is composed of her own prose and poetry braided together with her therapist’s notes.

Sedgwick, who suffered from breast cancer and was a long-time AIDS advocate, mused: “how permeable the identity of ‘survivor’ is to the undiminishing currents of risk, illness, mourning, and defiance.”{11} Sedgwick relished the first person plural pronoun “we,” describing it as permeable, a rich mesh of relationality that if not equal to love, at least occasioned it. TCJR congregates a critical community of individuals within the permeable relational net of “we,” who attempt to make an occasion for love and in doing so to open the prospect for a more welcoming, just, and sustainable world. With TCJR I hope to give the gift of “we” to a future “you” as a counter-hail that urges non-normative identifications. This counter-hail would not only invite you to imagine shared differences, which Sarlin suggests is the capacity of the “you,” but to also imagine difference as both independent and held in common.

The form of TCJR resembles that of the Japanese poetic form renga, which translates into English as “linked poem.” The product of collaboration, linked poems originated over 700 years ago, as poets would write in pairs or small groups, taking turns composing alternating stanzas. I was introduced to renga via Sedgwick, whose passion for poetry and Buddhism led me to an understanding of life itself taking the form of renga.{12} Life is like renga because living is a collaborative project, perhaps no more so than when one is ill or disabled. Or rather, when one is ill or disabled, the necessary codependence between humans is brought into relief. I wanted to bring this collaborative project of living and of speaking for the sake of survival to fruition in a film, to preserve the collective self-care that these trying times demand. Call it a war cry delivered by twenty-seven speakers—mostly women of color, young and old, of differing health status, sexual orientations, racial and gender identities. Like a life-threatening diagnosis, TCJR asks for a reevaluation of priorities, posing the question of what kind of life is worth living and what kind of world is worth fighting for.

Lorde’s essay, “Poetry is Not a Luxury,” first published in 1977, begins with these words: “The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives.”{13} Later she continues: “In the forefront of our move toward change, there is only our poetry to hint at possibility made real. Our poems formulate the implications of ourselves, what we feel within and dare make real.”{14} Lorde’s words guide me, as they did in the making of TCJR, to take up a resistance to story. For Lorde, poetry operates differently and serves a different function than story. Poetry grants us that “quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives.” Poetry is a necessity for examining ourselves and our worlds, and our embeddedness in our worlds. Poetry points to the ways we can imagine new worlds.

As I move toward a conclusion of this rumination I thought I would attempt to devise a renga by revisiting and linking some key phrases culled from TCJR:

We were telling the same stories over and over and over

What are the words you do not yet have, what is it that you need to say . . .

Many battles came with cancer. I almost became homeless. I lost my job.

So, there were many battles inside of this battle.

There’s something about it becoming the story of my life that I’m afraid of.

You understand . . . that you are different from other humans . . .

maybe you’re not even human anymore.

Figure 3. Production still. THE CANCER JOURNALS REVISITED, Lana Lin (2018). Courtesy Nan Zhang.

Figure 3. Production still. THE CANCER JOURNALS REVISITED, Lana Lin (2018). Courtesy Nan Zhang.

Returning to The Cancer Journals is to draw strength from its insights and also to gain traction from the friction that is generated as it brushes against the present moment. This friction is not unlike that of an original brushing against its translation, as Walter Benjamin elaborates.{15} Benjamin asserts that a translation is a means of coming to terms with the foreignness of language. Transferring this to filmmaking practice, I understand filmmaking as a way of coming to terms with the foreignness of others, and the foreignness of myself. Filmmaking can mark and hold difference the way in which pronouns can.

According to Benjamin, the translation emerges from the afterlife of the original, transforming it. I am struck by two other afterlives that are relevant to my concerns. In Autobiography of a Disease, Patrick Anderson narrates his medical and pathological travails from the collective viewpoint of his bacterial infection.{16} The illness that rendered him in pieces could not be returned as a singular or totalizing story. His pathogens haunted him as a counter-hail from the non-normatively human, or better, the assemblage of human/nonhuman that he/they has/have become/is becoming. Anderson, including the bacteria, medication, and prostheses that will perpetually cohabitate his body, meditates upon what he names the afterlife of illness. In the afterlife of illness, the illusion of a unitary self is destroyed; in its wake, the self is pluralized. TCJR is its own kind of autobiography of disease, or perhaps more suitably, it culls multiple autobiographies into the cinematic afterlife of disease.

And finally, Saidiya Hartman lends depth to this association in her powerful resurrection of the afterlife of slavery that lives on in empty archives and untold stories. Returning to her African roots, Hartman searches in vain for the teller of a tale that would connect her to a past that her kin, descendants of slaves, had released from memory or had chosen to purge. Toward the end of her journey along a slave route in Ghana, Hartman calls forth a “dream of the world house” which shelters the common dreams of fugitives, refugees, and migrants.{17} It is not a unified community that comes together in this house, but a collective of disparate dreamers who, as she imagines, becomes together. From Anderson and Hartman, we learn that stories of the broken must themselves be broken—open, in the sense of pushing back on the coded and conventional logics of “proper” storytelling. The world house is the result of collective becoming, a worldbuilding that takes as its materials not well-worn, familiar stories but rather the poetic province of dreams. From this world house, we may hear, if they are given audience, unstorified counter-hails, for the counter-hail need not conform to a story. Going beyond the confines of the storybook house to the “dream of the world house” can make possibility real.

Title Video: The Cancer Journals Revisited, Lana Lin (2018)

{1} Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow, “Beyond Story: an Online, Community-Based Manifesto,” World Records 2 (Fall 2018).

{2} Adrienne Rich, “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision,” College English 34, no. 1 (October 1972): 18-30.

{3} Barton Byg, Landscapes of Resistance: The German Films of Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 2.

{4} “Breast Cancer: A Black lesbian feminist experience Part III Power vs. Prosthesis”; Audre Lorde Papers, box 16; series 2.1; folder 19; Spelman College Archives. I thank Toby Lee for pointing out to me the significance of this crucial passage. See Toby Lee and Lana Lin, “Filmmaking in a Minor Key,” Millennium Film Journal 70 (October 2019): 60-69.

{5} Audre Lorde, The Cancer Journals (Argyle, NY: Aunt Lute Books, 1980), 21.

{6} Alisa Lebow observes that the subjectivity of first person cinema, like its associated grammatical structure, can be either singular or plural. She might have titled her book The Cinema of We had it not been such a “ghastly clunker.” Alisa Lebow, ed., The Cinema of Me: The Self and Subjectivity in First Person Documentary (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 2-3.

{7} Lorde, The Cancer Journals, 21.

{8} Paige Sarlin, “Between We and Me: Filmed Interviews and the Politics of Personal Pronouns,” Discourse 39, no. 3 (2017): 320.

{9} Pooja Rangan, Immediations: The Humanitarian Impulse in Documentary (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 194.

{10} Arthur Frank, The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

{11} Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Tendencies (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), 3.

{12} I come to this conclusion in my book Freud’s Jaw and Other Lost Objects: Fractured Subjectivity in the Face of Cancer (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017).

{13} Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley: Crossing Press, 2007), 36.

{14} Ibid., 39.

{15} Walter Benjamin, “Task of the Translator,” in Illuminations (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 69-82.

{16} Patrick Anderson, Autobiography of a Disease (New York: Routledge, 2017).

{17} Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), 233.