Platform Politics: Netflix, the Media Industries, and the Value of Reality

Joshua Glick

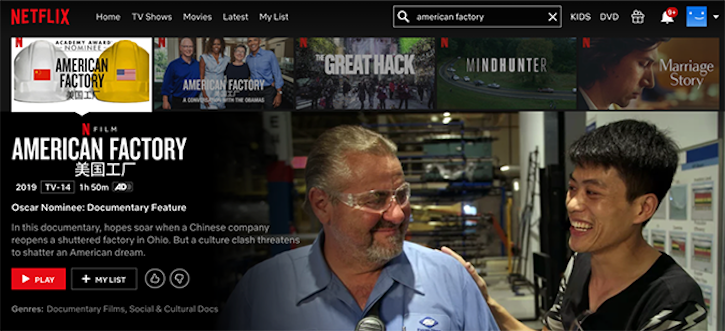

It was a match made at Sundance. The day after Julia Reichert and Steven Bognar’s much anticipated American Factory (2019) premiered at the Prospector Square Theater, members of their production team confidentially met with interested parties at the Washington School House Hotel to negotiate a three million dollar distribution deal. As other high-profile documentaries had fetched multimillion dollar bids during their festival runs, it wasn’t simply the price tag that was significant. It was the fact that American Factory convened some of the most influential players in the field. Participant Media, which has served as a philanthropic investor and outreach vehicle for socially engaged features since its founding in 2004, financed and co-produced American Factory. Netflix had partnered with Participant the previous year on Alfonso Cuarón’s neo-neorealist Roma (2018) and was no stranger to Sundance acquisitions. For each festival, the Washington School House Hotel served as the company’s home base as they went hunting for projects that tapped into the zeitgeist and generated awards buzz. Barack and Michelle Obama’s recently created Higher Ground Productions had signed a multi-picture contract with Netflix and was looking for their first big film. Also at the table, assisting with contract negotiations, was Submarine, which had helped broker distribution deals for six of the last twelve Oscar-winning documentaries.{1}

American Factory was an ideal documentary for these parties to collaborate on. It explores the initial production cycles of Fuyao Glass America, a Chinese-owned glass manufacturing company which had recently arrived at the Rust Belt town of Moraine, Ohio, literally setting up shop in a former General Motors auto plant. On a symbolic level, American Factory offered the opportunity to form the liberal analogue to the conservative media coalition of Donald Trump, Steve Bannon, and Fox News, and to repudiate the kind of alt-right propaganda they generate. In practical terms, American Factory focused on a topical subject that was at once hyper-local and transnational in scope, and would thus appeal to viewers domestically and abroad and potentially even across socioeconomic divides.

Reichert and Bognar, who have been making incisive social documentaries and teaching production in the region for over four decades, created a sweeping portrait of day-to-day factory life, capturing the perspective of Chinese and American workers and managers. Moreover, the film managed to do this in a media landscape that either completely effaces the sight of manual labor from popular film and television or sensationalizes it within the trappings of reality TV (Ice Road Truckers, Deadliest Catch, Undercover Boss, etc.). Instead, American Factory presents a dignified account of what factory labor looks like and what it means to those who do it. The documentary’s tight focus on compelling characters, however, tends to draw attention to interpersonal relationships rather than contextualize the state of US manufacturing or advocate for any kind of transformative change to workplace conditions.

As the film unfolds, it becomes more devoted to examining the “clash” of American versus Chinese cultures (depicting the former as “pro” and the latter as “anti” union), rather than delving into how corporate capitalism exploits workers around the globe. Looking to the future of industrial production in the US, the film concludes with the lofty call for all stakeholders, spanning those on the shop floor to the C-suite office, to come together in civil dialogue to determine the “future of work,” instead of acknowledging the ongoing need for labor organizing—albeit, perhaps, in new and creative ways. In the Netflix promo featuring a roundtable discussion with the filmmakers and the Obamas, the former president amplifies this sentiment that goodwill and an open heart can transcend any system, bringing people of differing perspectives together: “If you know someone, if you talk to them face to face, if you know what their story is, you can forge a connection. You may not agree with them on everything, but there is some common ground to be found and you can move forward together.” American Factory went on to receive rave reviews and a slew of awards, most notably the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature.

American Factory was at once a prestige project for Netflix and part of the studio’s larger effort to reboot liberal documentary for the streaming era. To be sure, nonfiction under the Netflix tent includes a vast array of genres, including sports chronicles, biopics, true-crime serials, and social issue features. Nonetheless, as the company has built its slate of films, it has also developed a house style defined by the character-focused charge and high production values of classical Hollywood and the relentless exposition of legacy television journalism. The popularity of these films naturally benefits Netflix’s bottom line, and they serve an important role in garnering accolades and demonstrating its social conscience. Certainly not every documentary that appears on the platform conforms to this format, especially those select projects made by auteurs such as Ava DuVernay, Werner Herzog, and Errol Morris. These individuals come to the negotiating table with an illustrious oeuvre, thus commanding lucrative deals and a high degree of creative flexibility.

Netflix’s investment in nonfiction has provided a venue for films that have struggled to find a home in mainstream television or the theatrical market, and has expanded the demographic for documentary. Additionally, it has meant opportunities for filmmakers eager for an upfront paycheck as well as a way to showcase their work to a large audience. However, these opportunities have come with significant constraints concerning film form, the way projects are packaged for audiences, and the conditions under which they live on- and offline. Netflix views distribution as not simply the mechanisms that enable media to reach viewers, but carefully guarded pipelines of lucrative proprietary data. In turn, these restrictions can neutralize the films’ rhetorical charge, limit viewers’ understanding of or relationship to the film’s subject, and curb the possibilities for community engagement.

Netflix is ultimately helping to drive a broader shift of documentary into the mainstream of the media industries and popularize its own form of edutainment storytelling. The larger surge stems from the aggressive move of “content”-hungry digital distributors into the realm of production, the relatively low cost of nonfiction, and a desire for “authentic” and “empathetic” storytelling in an era of clickbait journalism, disinformation, and a reality TV presidency. Scholars have paid too little attention to this flurry of nonfiction activity. One reason is that research on documentary and the media industries is frequently siloed into separate endeavors. The former often focuses on close readings of individual films, many of which stand against Hollywood’s traditional genres of storytelling and industrial forms of media making. The latter tends to focus on mainstream film and television and also reaches beyond the screen itself, delving into the policies and labor practices that shape media production, distribution, and exhibition. As film historian Tom Schatz notes, there is too often a gap between a consideration of “media ownership,” the “means and modes of production,” and close analysis of the “products” themselves.{2} These divides play out in examinations of Netflix. Much has been written about the snail-mail-distributor turned mega-studio. Scholars have emphasized the company’s innovative approach to production and distribution (framing Netflix as an online global television network), its reshaping of viewing habits, and its creation of individual genre-bending series such as Orange is the New Black (2013-19), House of Cards (2013-18), and Stranger Things (2016-).{3} Understanding the implications surrounding documentary’s close relationship to the media industries and the entrenched place it has come to occupy within the “streaming wars,” requires greater attention to both macro issues of political economy and fine-grained issues concerning narrative form. Analyzing Netflix’s documentary ventures not only reveals the increasing interconnections between Hollywood, Silicon Valley, and Washington D.C., but also exposes the contested value of documentary within our contemporary political culture.{4}

****

Changing Channels in the Age of Media Convergence

Documentary has been part of Netflix’s core offerings since its website launch in 1998. The company made a name for itself by connecting the cheap-to-mail format of the DVD to the emerging e-commerce business and the home rental market. Netflix attracted customers with its low-cost subscription plan, large inventory, and algorithmic recommendation system.{7} As scholar and festival programmer Sudeep Sharma argues, in its early years the distribution hub was more akin to a “digital newsstand” than a public library, archive, or museum. Netflix differentiated itself within a crowded marketplace through its support of harder-to-access documentary, art house cinema, Bollywood musicals, anime, and martial arts films.{8} These were films that behemoth rental chains neglected in their brick-and-mortar stores. They were also easier to acquire than studio features, which frequently had expensive licensing fees.{9} Blockbuster stressed big budget new releases with documentaries grouped into a small “special interest” section comprising everything from Jane Fonda workout videos to sports compilations. Hollywood Video also primarily stocked popular fiction along with a stronger selection of foreign films and cult classics. Movie Gallery served rural areas and housed a tantalizing “adult section.” Suncoast Motion Picture Company specialized in the for-sale market of underground films and collector editions of studio features.{10}

Netflix’s Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos, a veteran of the rental industry by the time he joined the company in 2000, saw documentary as more than a line item of inventory or something purely driven by audience data. An admirer of liberal television producers such as Norman Lear (especially for the wide viewership attracted by his network series), Sarandos embraced a centrist liberal view of social documentary, promoting films that shine a light on the experiences of marginalized groups, raise awareness of human suffering, and promote civil dialogue. At the same time, such films tend to shy away from strong critique or delving deeply into the systemic forces that shape individual lives.{11}

Figure 1. Leslie Walker, “Now Showing in Your Mailbox,” WASHINGTON POST, August 11, 2002.

Figure 1. Leslie Walker, “Now Showing in Your Mailbox,” WASHINGTON POST, August 11, 2002.

Netflix was not the first organization to realize the multifold value of documentary.{12} The company capitalized on what had been growing popular interest in nonfiction for over a decade. While 1989 is remembered as the year Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies, and videotape and Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing stormed the festival circuit, garnering big prizes and yielding high box office returns, it was also the year Michael Moore’s Roger & Me enjoyed a similar reception. In the immediate years that followed, aging studios such as Warner Bros., emerging players such as Miramax, and specialty distributors such as Zeitgeist Films gravitated toward documentary, marketing it as another form of gritty, auteur-crafted indie cinema. Of course, money was a motivating factor. Nonfiction is frequently cheaper to produce, given the comparatively low costs of scripts, actors, and post-production effects, as well as the chance to repurpose archival footage from a company’s film libraries. There were some salient documentary initiatives in the public media sphere that emerged during this period, including the establishment of POV in 1988 and ITVS in 1989. Nonetheless, the general decline of public subsidies for the arts (especially for formally experimental or politically charged projects) that accompanied the neoliberal restructuring of government funding opened the nonfiction field to commercial investment{13}

The post-9/11 “War on Terror” combined with the rise of DVDs, social media, and video streaming further heightened the visibility of documentary in public life. During this period documentary provided an urgent challenge to the Bush administration’s war abroad, repressive political culture at home, and tenuous relationship to factual discourse. In a special documentary-themed Cinéaste dossier, critics discussed the proliferation of nonfiction in theaters, television, and DVD, noting how The Fog of War (Errol Morris, 2003), Fahrenheit 9/11 (Michael Moore, 2004), Control Room (Jehane Noujaim, 2004), Uncovered: The Whole Truth About the Iraq War (Robert Greenwald (2004), and My Country, My Country (Laura Poitras, 2006) in different ways engaged with the antiwar effort, which was receiving scant or distorted treatment in the mainstream media.{14}

Throughout its first decade in business, many of Netflix’s most widely discussed projects were its documentaries. The studio collaborated with filmmakers and organizations across the commercial and nonprofit sectors. In 2003 Netflix partnered with distributor Docurama to launch Netflix First, where documentaries would be made available on the platform for thirty to sixty days following their festival and theatrical run. Docurama’s Steve Savage commented, “this is sort of the equivalent of opening a film in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago and getting the critics to create a buzz.” The initial slate included a campaign documentary about gay write-in candidate Tom Ammiano, See How They Run (Emily Morse/Kelly Duane, 2002), a photographic exploration of the Mountain South, True Meaning of Pictures: Shelby Lee Adams’ Appalachia (Jennifer Baichwal, 2002), and an observational portrait of a homeless woman living in Central Park, Jupiter’s Wife (Michel Negroponte, 1995). Similar deals followed with Kino-Lorber, HBO Video, and Columbia Tristar Home Entertainment. Netflix also joined forces with public media’s American Experience to create a ninety-day rental window for the Sundance and Oscar-nominated Daughter from Danang (Gail Dolgin and Vincente Franco, 2002), a documentary which followed Heide Bu’s emotionally-wrenching journey to find her Vietnamese birth mother.{15} Netflix made POV titles available for one to four months immediately after their television premiere. Executive director Cara Mertes told Video Business that Netflix is “an ideal partner in our effort to broaden the availability of POV titles.”{16} A special “POV Collection” tab made available the Sundance-winning Farmingville (Carlos Sandoval/Catherine Tambini, 2004), a film about community reaction to the attempted murder of Mexican day laborers on Long Island. On occasion, Netflix distributed noteworthy projects rejected by bigger companies, such as Tim Robbins’ Embedded Live (2005), a filmed performance of the actor’s satirical play about the Iraq War that featured a “chorus of masked caricatures.” When critics labeled the production “agitprop,” Sarandos, in similar fashion to social media companies, tried to assume the seemingly passive role of host. He claimed, “we are not providing a political position, but providing a platform.”{17}

Netflix began to take an active role in producing and distributing films when it launched Red Envelope Entertainment around 2005. Red Envelope teamed up with IFC TV, Roadside Attractions, and ThinkFilm to provide niche projects with post-production resources and aid for distribution and festival promotion. It produced the comedy special Zach Galifianakis Live at the Purple Onion (Michael Blieden, 2005) along with the documentary This Film Is Not Yet Rated (Kirby Dick, 2006) about the history of the MPAA rating system. It hosted theatrical screenings for Super High Me (Michael Blieden, 2007), and helped distribute HBO’s Born into Brothels (Zana Briski and Ross Kauffman, 2004), a loosely vérité documentary about the children of sex workers in the red light district of Calcutta. Netflix gravitated to the latter film’s heartfelt portrayal of innocent children surviving deplorable conditions and the ways it made for an empathic viewing experience, especially for Western audiences. Equally important to Netflix was how the film’s pedigree was affirmed at each step of its journey, from the point that it received initial backing from the Fledgling Fund, an enthusiastic Sundance premiere, praise from Al Gore, and eventually an Oscar prize. Born into Brothels presents a story of uplift, however, it distorts the sociology of the red light district and inscribes the onscreen characters into the familiar roles of “foreign other” and “white savior,” tropes that loom large in the Western cinematic imagination. Just as elite vetting and the embrace of progressive topics would become common practice at Netflix so, too, would the studio’s films increasingly oversimplify complex social realities to make for more gripping narratives as well as mask ethical tensions regarding the power dynamics of production.{18}

Figure 2. Netflix tab for “Documentary,” Wayback Machine, August 3, 2004, Internet Archive.

Figure 2. Netflix tab for “Documentary,” Wayback Machine, August 3, 2004, Internet Archive.

By the turn of the decade, Netflix had shifted from DVD to streaming and would begin to assert itself as a production outlet, much to the anxiety of legacy studios. As Netflix scaled up its operations, it would continue to keep its sights on documentary.{19}

****

From Rental Hub to Studio

The myriad connections between Netflix and the Democratic Party bolstered the company’s liberal reputation and fashioned a progressive lens through which viewers saw its films. The Hollywood Reporter featured power couple Ted Sarandos and Nicole Avant on the cover of their special “Hollywood & Politics” issue. Inside, articles catalogued how they bridged Hollywood, Silicon Valley, and Washington D.C., connecting the spheres of film, tech, and government. Sarandos and Avant had raised big money for both of Barack Obama’s presidential campaigns and Avant served as ambassador to the Bahamas during his first term. Sarandos was known to be a close confidant and informal consultant (film recommender-in-chief) to the former president.{21}

Figure 3. (L) “Hollywood & Politics,” Cover, THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER, April 25, 2012. (R) Tatiana Siegel, “Obamas

Settling Into New Role as Netflix Producers,” THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER, August 7, 2019.

Figure 3. (L) “Hollywood & Politics,” Cover, THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER, April 25, 2012. (R) Tatiana Siegel, “Obamas

Settling Into New Role as Netflix Producers,” THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER, August 7, 2019.

It was under the leadership of Lisa Nishimura that documentary would come to play a crucial role in Netflix’s transition to a full-fledged studio. Before joining Netflix in 2007, Nishimura had worked first for Island Records and then Palm Pictures, specializing in the distribution of independent music and film from around the world. Hired by Sarandos to acquire international fiction and television series, she moved on to nonfiction where she was promoted to Vice President of Documentary and Comedy. In early 2019 she became Vice President of Independent Film and Documentary Features. Nishimura touted the power of media to educate audiences about pressing social issues but remained adamant about the need to make it enjoyable to watch. In a KCRW interview with journalist Matt Holzman, she discussed how a good documentary should be a gripping story with compelling characters rather than a dry narrative that people need to endure like a kind of civic medicine. This outlook guided Netflix’s approach to production and dovetailed with how the studio began to see itself as an entertainment company.{22}

At the same time that David Fincher was creating Netflix’s hit series House of Cards, Nishimura was busy acquiring The Square (Jehane Noujaim, 2013), the Sundance-winning exploration of the 2011 democratic uprisings in Tahrir Square and their aftermath. Netflix’s acquisition and promotion of the film as a rebranded “original” allowed the company to stake a greater claim to world-historical relevance and prove that theatrical release was not essential for recognition and widespread interest. The Square’s celebration of social media as a tool for democratic action against the regime of Hosni Mubarak had particular appeal. It resonated with the way Netflix wanted viewers to view the studio. As media scholar James Gilmore argues, The Square’s dissemination through Netflix “highlights the political potential of media spreadability.”{23} The film drew on over 1600 hours of footage from protesters, spending ample time showing how they used their phones and mini DV cameras to document the series of events. Washington Post critic Ann Hornaday wrote that watching the film feels like being connected to the “nervous system” of a movement.{24} Also appealing to Netflix was The Square’s tight focus on freedom-fighting protestors taking on an oppressive system. Noujaim described her filmmaking approach as “(telling) the story through the eyes of characters.”{25} This meant filtering the events of the Arab Spring through the experiences of four individuals, each with a different relationship to the uprising: a student, a folk singer, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, and an actor. The film’s framing, however, ultimately portrays the uprising as an epic clash of good versus evil, while mostly avoiding in-depth examination of the tensions within the movement or the challenges of shifting beyond the occupation of the Square itself.{26}

Nishimura acquired films that had already received festival prizes. Contemporaneously, she worked with directors to create films or miniseries from the ground up. With a fast-expanding inventory of commissions and acquisitions, it became harder, in some sense, to decipher what made for a “Netflix documentary.” Major categories came to include true crime, science and technology, nature and environment, history, sports, human rights, and music. Each one of these developed its own common themes, modes of address, and formal tropes. The constant rotation of films on the platform and the highly “personalized” way they appeared for each individual further created the impression of infinite variety.

Nonetheless, this period marked a transition for Netflix from distributor carrying a rotating array of old and new documentaries produced elsewhere to a studio with a more clearly defined brand that created and curated its own fare. Netflix’s house style was less an air-tight checklist of attributes than a guiding logic. Films tended to address a social issue relevant to our contemporary moment; for example, mass incarceration, the climate crisis, the humanist power of art, corporate corruption, the benefits of cultural exchange, and the legacy of historical trauma. The subject was then emplotted in a narrative that involved elements of classical Hollywood storytelling as well as television journalism. From the former, the films drew on charismatic characters or small groups of individuals confronting some kind of central challenge or set of extraordinary circumstances. From the latter, they borrowed a steady flow of expository devices (voice-over, onscreen monologues, title cards, interviews) to guide the viewer through a subject. These techniques aim to clearly orient spectators towards a readily understood world as well as create a viewing experience akin to how scholar Kevin Glynn describes of 1980s “hyper visible” telejournalism as intensely vivid, immediate, and dynamic.{27}

Figure 4. Netflix Advertisement, THE SQUARE (Noujaim, 2013).

Figure 4. Netflix Advertisement, THE SQUARE (Noujaim, 2013).

The approach may include a beginning-to-end score, elaborate graphics, fast-paced editing, vérité flourishes, drone photography, and 4K image resolution. While not costing big figures compared to fiction, Netflix nonfiction production values are high compared to other models of commercial and nonprofit documentary. The average budgets for Netflix originals circa 2019 ranged from about $500,000 to 5 million. Acquisitions began at around $25,000 and went as high as 10 million. For commercial broadcast and cable, documentaries would rarely exceed 1 million dollars and for public media, the costs are usually between about $2-300,000.{28} Netflix took cues from HBO, whose famous tagline, “it’s not TV, its HBO,” helped to distance its programming from network broadcast and cable outlets. Under the guidance of doc maven Sheila Nevins, HBO gave provocative, socially engaged topics a “cinematic” treatment. HBO broadcast long-form features and multi-part series with no commercials and without the same censorship restrictions as network fare. The company poured big money into projects and courted well-known filmmakers to direct. What began to differentiate Netflix from HBO was not only its system of delivery (first DVD rental and then streaming) and the sheer scale of output, but its programming strategy. HBO simultaneously pursued two different tracks: the “high” one of auteur features (some of which took a more experimental approach) and the “low” one of salacious, tabloid-style series. While Netflix trafficked in each of these areas, it also found new ways of bringing them together within a single film or miniseries.{29} This storytelling strategy has led to a substantial viewership for films that otherwise could have been pigeonholed as “niche.” But it has limited the breadth of film styles and the diversity of filmmakers who are able to flourish on the platform. Specifically, it has resulted in a representational schema where characters take center stage and their social world often remains at a distance or is left as textured backdrop. In turn, this house style discourages viewers’ ability to draw connections between individual conditions and broader systemic forces. For example, true crime series such as Making a Murderer (Laura Ricciardi, 2015), Drug Lords (Mike Welsh, 2018), and Wild Wild Country (Maclain Way, 2018) place more emphasis on the suspected killer’s personality or the tantalizing details of social transgression than the failings or inequities of the US legal system. Nature films such as Chasing Coral (Jeff Orlowski, 2017) and Down to Earth with Zac Effron (Darin Olien, 2020) treat the climate crisis as less a subject to be critically understood than a constellation of spectacular images of the non-human environment to behold. Even Our Planet (Alastair Fothergill, 2019), a series that directly addresses the human-made consequences of climate change, tends to disassociate human society from environmental impact. Music documentaries such as Keith Richards: Under the Influence (Morgan Neville, 2015), and Quincy (Rashida Jones, 2018) highlight the genius of an individual artist or ensemble (foregrounding rare bootleg recordings, stage performances, and home footage), but deemphasize ways that music both shapes and is shaped by cultural geography or is part of a social movement.

Netflix’s packaging of a documentary for advertising and outreach can also neutralize its rhetoric or theme. To return to American Factory, it was the theme of “culture clash” rather than that of class conflict or the shared experiences of factory work that was taken up and amplified in the film’s paratextual materials. The film marked a departure from Reichert’s past work, which offered in-depth explorations of the American feminist and labor movements throughout the twentieth century from an intersectional perspective.{30} Netflix promoted the film as a humanist portrait, and tried to contain what might have been its more political dimensions. One of the common thumbnail images of American Factory on the platform foregrounds the US versus China as the dominant trope. The description makes this juxtaposition explicit, noting that “a culture clash threatens to shatter the American dream,” as if the threat was singularly China rather than the transnational process of capitalist accumulation. The poster advertisement and the Netflix promo film featuring Barack and Michelle Obama echo these sentiments. For the former, the “conflict/courage” motif is distilled in the alliterative tagline, “cultures collide, hope survives.” Paratextual materials further reinforce this perspective. Participant Media’s “Discussion Guide” states that the film’s purpose is to “spark discussion around the future of work and how that future affects us all.” The guide also prominently claims that American Factory “does not promote an ideology or political agenda, but instead tells a powerful, personal story about how globalization and the loss of industrial jobs affects workers, communities, and the future of work.”{31}

Figure 5. (L) Frame Grab from Netflix website. AMERICAN FACTORY, Directed by Julia Reichert and Steven Bognar (2019: USA, Higher Ground, Participant, Netflix).

Figure 5. (L) Frame Grab from Netflix website. AMERICAN FACTORY, Directed by Julia Reichert and Steven Bognar (2019: USA, Higher Ground, Participant, Netflix).

While Netflix’s storytelling paradigm constitutes one kind of restrictive framework, the protocols that guide how films exist on- and off-line constitute another. This is of course not the way that Netflix likes to see itself, nor the way it is usually depicted in the popular press. In a New York Times article profiling the company’s Los Angeles headquarters, journalist Brooks Barnes describes the plush lobby as the “New Town Hall of Hollywood.”{32} The gigantic Sunset Boulevard headquarters appears open and transparent, a place that seems ideal for the happy intersection of creative, civic, and financial goals. Even as Netflix prides itself on the accessibility of its media and the freedom that artists have to create under its banner, the company is like a tightly run, vertically integrated studio as opposed to a “town hall.” Flexible forms of exhibition beyond the platform are rare. These deals are reserved for a very small group of well-known directors, whose work is deemed “award-worthy” or whose name commands power and urgency. For example, Netflix allowed Ava DuVernay to create an elaborate tour for 13th (2016) that ran parallel to its online exhibition. The documentary was shown in schools, libraries, and community centers across the country, often as part of educational programming concerning the crisis of mass incarceration.

A filmmaker’s standard “worldwide rights” contract gives Netflix firm control over how the film circulates and in what capacity; for example, documentaries as varied as Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady’s vérité-style look at the difficult experiences of three Jews who try to leave their Hassidic community (One of Us, 2017) and a multi-filmmaker series about how companies deceive consumers about the health risks of everyday products (Broken, 2019), are all largely confined to the individualized onscreen space of the platform. Moreover, the long-term status of a film on the platform is also precarious. A documentary might be prominently featured for a month before getting buried deep in the digital backlog. It might be removed from the selection options entirely if, for some reason, it is deemed controversial, with the filmmaker left no recourse or alternative distribution options. In regard to this point, Netflix is quick to foreground that its main purpose is to “entertain.” For example, in response to removing Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj (Richard A. Preuss, 2018) from the platform in Saudi Arabia because it was highly critical of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Hastings told a packed New York Times DealBook Conference, “we’re not in the news business. We’re not trying to do ‘truth to power,’ We’re trying to entertain.”{33} Because filmmakers usually sign over all their rights to their projects, they have no chance to show their film in other settings.{34} Offline viewing has to be negotiated on a case-by-case basis.

Exhibition on the platform itself does not necessarily ensure meaningful engagement. One film seamlessly playing into another at the point of its conclusion facilitates a “binge-like” viewing experience rather than encouraging the viewer to pause and reflect on the film that just concluded or take a deep dive into supplementary materials. As media studies scholar Mareike Jenner argues, binging was marketed by Netflix as central to the platform’s appeal, a structured viewing practice where the “skip intro” and rotating “post-play” features create an “insulated flow” of moving-image content.{35} Additionally, information concerning viewership is deemed proprietary data and kept hidden from both the filmmaker and viewers. The exception is when these companies aim, as media scholar J.D. Connor has observed, to “flex in public” and trumpet the popularity of a particular film or television series. From the perspective of the streamers, the data is their most valuable asset.{36} Any film crew would find this information highly desirable. For the creators of advocacy-oriented documentaries and the broader communities involved in their production it is absolutely crucial. It is imperative to think of contemporary forms of digital distribution, following the line of interpretation advanced by Michael Curtin, Jennifer Holt, and Kevin Sanson, as not simply a technological delivery system, but a shift in “our ways of using media and our ways of socializing through media.”{37}

This is why the stakes surrounding distribution are not just about the aesthetic preference for a large-screen theatrical experience.{38} Rather, what is important, as scholar Angela J. Aguayo writes, is the social experience that different forms of exhibition afford.{39} Hosting a screening at a library, community center, or faith-based institution makes it possible for the film to address individuals en masse and to generate live interaction among those present. Thus, even as film and media theorist Jane Gaines claims that the potential for “political mimesis” might be produced by way of the film itself, it is the context of exhibition that remains critical for the corporeal “body back” phenomenon by which documentaries might render “activists more active, making them more like the moving bodies on screen.”{40} Foreclosing the possibility of documentaries screening openly in such venues curbs their political potential.

Knowledge of how a project is circulating and who is watching it also has very real implications for documentarians; for example, not knowing where or how many people are actually seeing a film limits their ability to negotiate future contracts and to supply this information in grant and funding applications. This information is significant for understanding the ways in which a film can be used as part of movement organizing or a particular advocacy campaign. Its absence creates what Liesl Copland calls “analytic black holes” that hurt filmmakers, audiences, and researchers alike.{41} This is not to say that knowing the quantitative metrics of who viewed the film where and for how much time should be seen as a kind of positivist proof of a film’s value. As scholars such as Meg McLagan and Brian Winston have argued, a fixation on connecting measurable, quantifiable “data” with proof of “impact,” discounts the qualitative ways that media makes meaning in the world, privileges short-term outcomes over long-term change, and devalues the process of filmmaking itself.{42} Nonetheless, being able to not simply reach, but mobilize viewers is directly connected to being able to better understand how people engage with films. Making any kind of social change—whether it is a matter of raising awareness about a pressing issue, electing a candidate, advocating for a piece of legislation, or reorienting a community’s understanding of itself—is contingent upon the context in which viewers interact with the projects.

****

Enter the Streaming Wars

Netflix now competes in a crowded arena of newly created platforms, each trying to claim cultural relevance and grow their subscriber base.{45} The studio’s venture into nonfiction has served as a model for Disney+, Apple TV+, HBO Max, and others to follow. Certainly, the comparatively low cost of documentary is helping to propel companies in this direction. Still, during this period of institution building, the more salient value of documentary concerns its social and symbolic meaning. Documentaries help form the architecture of the studios’ brand, signaling that they care about the climate justice, Me Too, and Black Lives Matter movements as well as projecting an image of the organization as transparent, authentic, and truthful. Documentaries dovetail with companies’ efforts to strategically recalibrate aspects of their filmmaking operations—for example, by speaking out against Georgia’s anti-abortion legislation, reducing their carbon footprint for shoots, or adopting inclusivity training for their employees. The exact form and subject of a nonfiction offering varies from streamer to streamer. Still, Netflix’s paradigm of educational yet entertaining long-form storytelling resonates across programming lineups.

Documentary affinities were on full display during the highly publicized platform launch events of 2019. Corporate leaders teamed up with creative talent to announce major collaborations and projects in the pipeline.{46} The unveiling of Disney+ at the D23 Expo in Anaheim was the culminating achievement of CEO Bob Iger’s three-decade plan to steer the entertainment empire toward quality branded content, technological innovation, and global expansion. As was the case with Disney’s “science factuals” and Disneyland television series (Walt Disney, 1954–58) in the 1950s, Disney+ documentaries serve multiple transmedia functions; for example, they draw people to the company’s family friendly parks, animated and live action films, and vast retail lines. Disney Insider (Isaac Webster, 2020), Disney Prop Culture (Jason Henry/Daniel Lanigan, 2020), and One Day at Disney (Fritz Mitchell, 2020) celebrate Disney labor, implying that “imagineering” extends across all sectors of employment. Behind-the scenes vignettes and day-in-the-life portraits spotlight the life stories of animators, producers, construction workers, radio DJs, voice actors, and veterinarians. The Hero Project (Maura Mandt, 2020) takes as its premise “inspiring kids” who perform selfless, humanitarian acts in their everyday lives. The series showcases how real-world citizens, just like the superheroes of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, are capable of extraordinary civic acts.{47}

Figure 6. “Netflix: The Red Menace,” Fast Company, January 2014.

Figure 6. “Netflix: The Red Menace,” Fast Company, January 2014.

Apple TV+’s Cupertino launch provided the opportunity for the company to align its long-standing image as a design maverick with that of a reinvigorated auteur. A highlight of the event was a promo video featuring fiction filmmakers Steven Spielberg, M. Night Shyamalan, Sofia Coppola, and J.J. Abrams waxing poetic about the artisanal craft of moving-image storytelling. Nonetheless, the event closed with Oprah Winfrey enthusiastically announcing her partnership to create documentaries with the tech giant. Discussing her desire “to build awareness through compelling conversation,” she outlined projects currently in the pipeline, including Toxic Labor, which would look at sexual harassment in the workplace and a yet-to-be named documentary which explores the complexities of mental illness across cultures.{48}

The Burbank convening and publicity surrounding HBO Max generated a lot of buzz about the platform’s deep IP library. In addition to tapping the parent conglomerate’s Warner Bros. film catalog and fan-favorite television shows (all 236 episodes of Friends), the platform also boasts a strong nonfiction agenda. The provocative documentaries of HBO, along with the docu-journalism of one of WarnerMedia’s key assets, CNN, will be vital going forward. Some initial offerings include Expecting Amy (Alexander Hammer, 2020), which focuses on Amy Schumer’s pregnancy and prep for her latest comedy special; Generation Hustle (Alex Gibney, 2020), about young people’s pursuit of fame and power; Bourdain (Morgan Neville, 2020), a profile of the late chef-turned-culinary evangelist, Anthony Bourdain; and The Scoop (Amy Entelis, 2020) which tracks female political reporters covering the presidential election.{49}

Figure 7. Jonah Weiner, illustration by Giacomo Gambineri, “The Great Race to Rule Streaming TV,” THE NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE, July 10, 2019.

Figure 7. Jonah Weiner, illustration by Giacomo Gambineri, “The Great Race to Rule Streaming TV,” THE NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE, July 10, 2019.

As the streaming wars play out, studios continue to preach that the pursuit of profitable entertainment and the public good are complementary rather than mutually exclusive goals. What these platforms have done is make a cross section of nonfiction more accessible to a wider demographic than was previously the case with legacy forms of theatrical distribution and broadcast. They have also created new venues for filmmakers (including those from marginalized and underrepresented groups) to showcase work that had a hard time finding traction in mainstream distribution. Much of the discourse surrounding corporate responsibility or “woke capitalism,” however, masks the ideological and stylistic pressures placed on documentaries that bear the streamers’ brand and how tightly controlled the flow of media is on their platforms. Despite access to vast back catalogs, these platforms’ pursuit of maximum eyeballs leads them to fetishize the contemporary and focus on a rotating array of recently created films. This climate of cultural amnesia discourages audiences from thinking about documentary as an art form that has developed over time and how past filmmaking practices and strategies could still be relevant today. In addition, the streamers are not only leading to a narrowing of film form, but also to a storytelling paradigm that distorts the complexity of our social world and forecloses what documentary’s relationship to it might be.

****

Platforms for the People

“Documentary activism takes shape when the filmmaker and the subjects, the screen and the audience, and event organizers and collaborators come together.”

—Svetla Turnin and Ezra Winton, co-founders of Cinema Politica, 2014{50}

“We must create a more generous and inclusive distribution landscape. That starts by growing a movement, creating ongoing dialogue, and shifting the culture behind how filmmakers engage in distribution.”

—Amy Hobby et al., “The Decency in Distribution Manifesto,” 2019{51}

Filmmakers as well as the broader public would benefit from streamers adopting a more inclusive approach to the media they support and a more lenient position regarding how media circulates on and off their platforms. Sarandos and Hastings have stated on numerous occasions that they support making data available, but their promises so often translate to little more than advertisements for a particular film’s appeal. Exactly who is watching which films and for how long remains hard, if not impossible, to ascertain. Panels and informal conversations at festivals, at the International Documentary Association’s “Getting Real” conference, and the online D-Word forum have provided spaces for documentarians to share experiences and create knowledge about how big streamers operate. Groups such as Brown Girls Doc Mafia, Asian American Documentary Network, and Distribution Advocates have, in pointed ways, been fighting for an equitable production and distribution ecology, one that grants more rights to filmmakers and places more women and people of color in positions of power. These groups are challenging the ways that companies make infrequent token hires and empty public statements about “beginning the conversation.”{52} At stake is the empowerment of creative labor, especially marginalized filmmakers, and the possibilities for their work to reorient our relationship to the world.{53}

A dispersed and localized media ecology nevertheless offers an alternative to the commercial streamers, both for its support of a diverse range of documentaries and greater flexibility concerning IP. These funders, production units, and distribution hubs are also more amendable to participatory and co-creative production models that embrace, as Patricia Zimmermann describes, a “polyphonic” practice where creative authority and input is distributed across multiple participants. They provide filmmakers with more freedom regarding exhibition, although their audiences are limited. For example, the left-leaning Field of Vision is a production house and exhibition venue for short-form documentaries that brings together investigative journalists, activists, and artists. They acquire and commission original projects that seek to experiment with the language of nonfiction representation in their engagement with social justice struggles around the globe. Importantly, as Field of Vision considers itself a “filmmaker-driven documentary unit,” filmmakers retain copyright and the raw footage associated with their projects.{54}

As stated on their website, OVID.tv aims to provide a “spark that you feel is missing on the big corporate platforms—for all of us who . . . want to be transformed, and to transform the world.” Its network of contributing independent distributors shapes the inventory, which climbed from around 300 to 800 titles during its first year of operation in 2019. Initial participants included such organizations as Women Make Movies (feminist media), Bullfrog Films (social justice films, ecocinema), Icarus Films (North American documentary, library of historical films), KimStim (international features, documentary), and dGenerate Films (independent films from mainland China). The particular contractual arrangements for films involve OVID and the rights holder, but OVID doesn’t retain legal control over the films and encourages their wide exhibition.{55}

PBS was initially slow to innovate online due to underfunding, its orientation to an aging viewership, and the fragmentation of its system, which resulted in individual stations operating with their own protocols and preferences. However, some stations have been making significant strides, doubling down on their civic mandate while trying to engage new (and younger) audiences through digital platforms. Promising initiatives include the expansion of content available on the PBS streaming app, interactive and short-form social media projects (POV Digital and Spark, Frontline’s Transparency Project), archival programming (American Archive of Public Broadcasting), and community media that conjoins local stations with a wider constellation of artists and filmmakers (Localore). Notably, PBS programming is underwritten through public-private partnerships and does not require the same kind of paid subscription plan as commercial platforms.{56}

Creating a more inclusive and democratic media infrastructure requires working on multiple fronts. This means more grassroots pressure to help renegotiate the power dynamics between commercial studios, the creative labor on which they rely, and the viewers who engage with their films. At the same time, it is imperative to continue supporting and developing alternative modes of production and distribution. New kinds of collaborations between filmmakers and their communities will be crucial in order to expand documentary practice and initiate the kinds of social transformations that it aims to bring about.

I would like to thank Alexandra Juhasz, Alisa Lebow, Jason Fox, and the anonymous World Records reader for their valuable feedback. The ideas for this article first emerged during the 2019 Society for Cinema and Media Studies conference. I am fortunate to have benefited from the sharp insights of Patricia Zimmermann, Chris Cagle, Brian Winston, and Gail Vanstone. The Open Documentary Lab at MIT provided a vibrant and welcoming environment to workshop this article over the past year. Special thanks to lab leaders William Uricchio and Sarah Wolozin for their constructive comments. Deep gratitude goes to Masha Shpolberg, Patrick Reagan, Raisa Sidenova, Katerina Cizek, and Lance Kramer for their help positioning Netflix within a broader media ecology.

Background Video: The History of Netflix (TV Junkie, 2016) / The Square (Jehane Noujaim, 2013) / American Factory: A Short Conversation with the Obamas (Netflix, 2019)

{1} Tatiana Siegel, “Sundance: Netflix Nabs ‘American Factory’ Doc for $3 million,” Hollywood Reporter, February 1, 2019; Tatiana Siegel, “Obamas Settling Intro New Role as Netflix Producers,” Hollywood Reporter, August 7, 2019; Mike Fleming, Jr., “Knock Down the House Sold for Record $10 Million,” Deadline, February 6, 2019; Will Thorne, “Obamas Discuss Higher Ground Productions,” Variety, August 21, 2019; Guy Lodge, “Netflix and the Obamas Raise the Stakes,” The Guardian, August 17, 2019; Email c; orrespondence between journalist Tatiana Siegel and Joshua Glick, August 6-10, 2020; Josh Rottenberg, “Q&A: Why the Obamas Became Producers of the Netflix Documentary, American Factory,” Los Angeles Times, August 16, 2019.

{2} Thomas Schatz, “Film Studies, Cultural Studies, and Media Industries Studies,” in Media Industries: Perspectives on an Evolving Field, eds. Amelia Arsenault and Alisa Perren (CreateSpace Independent Publishing, New York: 2016), 178; John T. Caldwell, “Para-Industry: Researching Hollywood’s Backwaters,” Cinema Journal 52, no. 3 (Spring 2013): 157-65.

{3} Cory Barker and Myc Wiatrowski, eds., The Age of Netflix: Critical Essays on Streaming Media, Digital Delivery, and Instant Access (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2017); Kevin McDonald and Daniel Smith-Rowsey, eds., The Netflix Effect: Technology and Entertainment in the 21st Century (New York: Bloomsbury, 2016); Mareike Jenner, Netflix and the Re-invention of Television (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018); Derek Johnson, ed., From Networks to Netflix: A Guide to Changing Channels (New York: Routledge, 2018); For an account of Netflix’s global reach, see, Ramon Lobato, Netflix Nations: The Geography of Digital Distribution (New York: New York University Press, 2019); Netflix Nations intersects with recent literature on contemporary global Hollywood that explores issues of localization, co-production, and transnational circulation; for example, Courtney Brannon Donoghue, Localising Hollywood (London: BFI, 2017).

{4} While major connections across the media cultures of San Francisco and Los Angeles can be traced back to New Hollywood if not before, there is a growing body of scholarship that looks at the contemporary nexus. Stuart Cunningham and David Craig, Social Media Entertainment: The New Intersection of Hollywood and Silicon Valley (New York: NYU Press, 2019).

{5} Chris Anderson, “The Long Tail,” Wired, October 1, 2004.

{6} Gina Keating, Netflixed: The Epic Battle For America’s Eyeballs (New York: Penguin, 2013), 45.

{7} Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York: NYU, 2006), 1–24. For Netflix’s early history, see, Keating, Netflixed, along with Netflix vs the World (Shawn Cauthen and Gina Keating, 2020); Marc Randolph, That Will Never Work: The Birth of Netflix and the Amazing Life of an Idea (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2019).

{8} For a survey of Netflix’s initial documentary offerings, see the Internet Archive’s “Wayback Machine” tool.

{9} Eric Hoyt, Hollywood Vault: Film Libraries Before Home Video (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 198–202.

{10} Daniel Herbert, Videoland: Movie Culture at the American Video Store (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014) 28–48; Joshua M. Greenberg, From Betamax to Blockbuster: Video Stores and the Invention of Movies on Video (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010), 122–9.

{11} Ted Sarandos interviewed by Matthew Carey, “How Ted Sarandos Transformed Netflix into a Global Doc Streamer,” IDA’s Documentary Magazine, November 25, 2015; Norman Lear interviewed by Ted Sarandos, “TV’s New Golden Age,” 2014 Paley IC Summit, posted January 29, 2015.

{12} Documentaries played in commercial theaters since the early twentieth century, however, they struggled to turn big profits. They also had difficulty on television in the age of the three networks. Michael Curtin, Redeeming the Wasteland: Television Documentary and Cold War Politics (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995). For early ratings data, see, for example, Appendix A in Robert Lee Bailey, An Examination of Prime Time Network Television Special Programs, 1948 to 1966 (New York: Arno Press, 1979).

{13} John Pierson, Spike, Mike, Slackers & Dykes: A Guided Tour Across a Decade of American Independent Cinema (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014), 103–22, 133–76; Yannis Tzioumakis, “Indie Doc’: Documentary Film and American ‘Independent’, ‘Indie’ and ‘Indiewood’ Filmmaking,” Studies in Documentary Film 10, no. 1 (2016): 1–21; Nora Stone, “Marketing the Reel: The Creation of a Multilayered Market for Documentary Cinema,” Dissertation, University of Wisconsin, 2018. For more on the broader commercialization of nonfiction during the 1990s–2000s (nature, travel, science programming, etc.), see, David Hogarth, Realer Than Reel: Global Directions in Documentary (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006), 19–40; Elfriede Fürsich, “Between Credibility and Commodification: Nonfiction Entertainment as a Global Media Genre,” International Journal of Cultural Studies 6, no. 2 (2003): 131–53. For shifts in public media, see, Laurie Ouellette, Viewers Like You? How Public TV Failed the People (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002); James Ledbetter, Made Possible By…: The Death of Public Broadcasting in the United States (London: Verso, 1998).

{14} Patricia Aufderheide, “The Changing Marketplace for Documentary,” Michael Renov, “The Political Documentary Today,” Paul Arthur, “Extreme Makeover: The Changing Face of Documentary” in “Special Focus on American Documentary Today,” Cineaste 30, no. 3 (Summer, 2005): 18–36.

{15} Daniel Frankel, Video Business 23, no. 24 (July 2003): 12; “Netflix Launches Netflix First and Unveils Docurama Partnership,” PR Newswire, June 16, 2003, 1; Holly J Wagner, “Netflix Exclusive Just First Step in Boosting Category at Docurama,” Videostore Magazine, July 29, 2003, 15; Steve Savage, quoted in Jill Kipnis, “DVD Video Net Rental Takes Off,” Billboard, August 2, 2003, 1; Ted Loos, “Dynamic DVDs: We’re Hooked,” Town & Country, June 2004, 99–100; Nicholas Thompson, “Netflix Uses Speed to Fend-Off Wal-Mart Challenge: Disks for Rent,” New York Times, September 29, 2003, C1; Holly J Wagner, “TV Airing a Big Plus for Documentaries,” Video Store Magazine, September 14–20, 2003, 25; Patricia Troy, “One-Stop Shops: From Acquisition to Distribution, Docurama, Criterion and Facets Multi-Media Manage to Do It All,” IDA’s Documentary Magazine, November 1, 2003; Sarah Jo Marks, “All Docs, All the Time: DVD Label Docurama Deals Exclusively in Nonfiction,” IDA’s Documentary Magazine, July 31, 2005; PR Newswire, “Netflix Offers Exclusive Rental of Daughter From Danang,” New York, November 10, 2003, 1.

{16} Cara Mertes, quoted in Jennifer Netherby, “Netflix to Debut PBS Series Exclusively,” Video Business 24, no. 24 (June 2004): 8; Holly J Wagner, “Netflix in New Deal to Boost Docs,” Video Store Magazine, June 27, 2004, 24.

{17} Marcy Margiera, “Netflix Aims for Pinpoint Accuracy,” Video Business 23, no. 45 (November 2003): 8; Marcy Margiera, “What’s Up, Docs?” Video Business 23, no. 41 (October 2003): 6; Ted Sarandos, quoted in Elaine Dutka, “Tim Robbins is Showing His Independent Streak,” Los Angeles Times, May 24, 2005, E4.

{18} Ted Sarandos, “Read the Speech That Sent a Wake Up Call to TV and Film Studios,” IndieWire, October 31, 2013. Partha Banerjee, “Documentary Born Into Brothels and the Oscars: An Insider’s Point of View,” Letter to the Executive Director, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, February 1, 2005; Pooja Rangan, “Immaterial Child Labor: Media Advocacy, Autoethnography, and the Case of Born Into Brothels,” Camera Obscura 75, no. 25/3 (December 2011): 143–77.

{19} Patrick Sauer, “How I Did It,” Inc., December 2005, 27; Larry Williams, “At City, Truth Can be Stronger Than Fiction,” Hartford Courant, January 15, 2004, D1; Alex Pham and Jon Healey, “Telling You What You Like,” Los Angeles Times, September 20, 2005, A1; David Pogue, “A Stream of Movies, Sort of Free,” New York Times, January 25, 2007, C1; It is easy to forget just how crowded and contingent the online video and rental landscape was in the early 2000s. Blockbuster turned down an offer to purchase Netflix for $50 million in 2000.

{20} Lisa Nishimura, interviewed by Mario Calabresi at the International Journalism Festival, Perugia, Italy, April 12, 2017.

{21} Tina Daunt, “Hollywood & Politics,” Hollywood Reporter, May 4, 2012.

{22} Joy Press, “This is the Netflix Exec to Thank for Your Wild, Wild, Country Binge,” Vanity Fair, June 15, 2018; Joe Flint, “Meet the Woman Who Made Netflix’s Tiger King Must-See Quarantine TV,” Wall Street Journal, May 10, 2020; Lisa Nishimura interviewed by Matt Holzman, part of The Business with Kim Masters, KCRW podcast, December 10, 2018.

{23} Greg Gilman, “Netflix Acquires Egyptian Protest Documentary,” The Wrap, November 4, 2013; James N. Gilmore, “Circulating The Square: Digital Distribution as (Potential) Activism,” in Cory Barker and Myc Wiatrowski, eds. The Age of Netflix: Critical Essays on Streaming Media, Digital Delivery, and Internet Access (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2017), 29-37.

{24} Ann Hornaday, “The Square Movie Review,” Washington Post, January 16, 2014. Facebook and Twitter are used to coordinate protests. One of the protagonists, Khalil, becomes a leader in a counter-surveillance movement, documenting instances of state violence and uploading the films to YouTube. When Egyptian censors barred The Square from being shown domestically, it was streamed on YouTube as well as pirated and disseminated underground.

{25} Jehane Noujaim, quoted in Max Fisher, “The Square is a Beautiful Documentary. But Its Politics Are Dangerous,” Washington Post, January 17, 2014.

{26} Karim Amer, quoted in Thomas L. Friedman, “From the Pyramid to the Square,” March 2, 2014, New York Times, SR11; Steve Dollar, “The Square Filmmakers Capture a Revolution – and then an Oscar Nomination,” Washington Post, January 2014, C1; Nick Vivarelli, “The Square Circumvents Egyptian Censors With YouTube Version,” Variety, February 25, 2014; Gregory Stephens, “Recording the Rhythm of Change: A Rhetoric of Revolution in the Square,” Bright Lights Film Journal, May 7, 2014; Evan Hill, “The Egypt Outside The Square,” Aljazeera America, January 16, 2014.

{27} Kevin Glynn, Tabloid Culture: Trash Taste, Popular Power, and the Transformation of American Television (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000), 20-45.

{28} Peter Hamilton, Netflix: What You Need to Know Now! 2019-2020, (New York: Peter Hamilton Consultants Inc, 2020), DocumentaryBusiness.com.

{29} Thomas Mascaro, “Overview: Form and Function,” in The Essential HBO Reader, eds. Gary R. Edgerton and Jeffrey P. Jones (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2008), 239–261.

{30} For an overview of the extraordinary career of Julia Reichert, see Patricia Aufderheide, “Julia Reichert and the World of Telling Working Class Stories,” Film Quarterly 73, no. 2 (December 9, 2019).

{31} American Factory Discussion Guide, Participant Media and Higher Ground, 2019; Talib Visram, “Obama’s Netflix Doc American Factory to Launch Impact Tour,” Fast Company, August 29, 2019.

{32} “The Town Hall of Hollywood: Welcome to the Netflix Lobby,” New York Times, July 14, 2019.

{33} Reed Hastings, interviewed by Andrew Ross Sorkin, New York Times DealBook Conference, November 6, 2019; Tyler Hersko, “Netflix’s Latest Claim That It Wants Data Transparency Rings Hollow,” IndieWire, September 27, 2019; Ben Travers, “Netflix Claims ‘When They See Us’ Is Its Most-Watched Series… Just in Time for Emmy Voting,” IndieWire, June 12, 2019.

{34} See the D-Word blog discussion, “Dealing With Netflix,” October 26, 2019. Peter Hamilton, Netflix 2020.

{35} Jenner, Netflix, 125-37; Brooks Barnes, “In Bid to Conquer Oscars, Netflix Mobilizes Savvy Campaigner and Huge Budget,” New York Times, February 17, 2019.

{36} J.D. Connor, “What’s Contemporary About the Academy Awards?” Post45, February 24, 2019.

{37} Michael Curtin, Jennifer Holt, and Kevin Sanson, “Introduction: Making a Revolution,” in Curtin et. al., Distribution Revolution: Conversations about the Digital Future of Film and Television (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 5.

{38} Anne Thompson, “The Spielberg vs Netflix Battle Could Mean Collateral Damage for Indies at the Oscars,” IndieWire, February 28, 2019; Andrew Pulver, “Netflix Responds to Steven Spielberg’s Attach On Movie Streaming,” The Guardian, March 4, 2019; Addie Morfoot, “Streamers Give Documentary Field a Boost,” Variety, November 5, 2019.

{39} Angela J. Aguayo, Documentary Resistance: Social Change and Participatory Media (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 1-23.

{40} Jane Gaines, “Political Mimesis,” in Collecting Visible Evidence, eds. Jane Gaines and Michael Renov (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 100.

{41} Liesl Copland, “Digital on Demand: Show Us the Numbers,” IndieWire, September 10, 2013; Lene Bech Silesen, “Do Documentary Filmmakers Need Data About Their Audiences?” Columbia Journalism Review, August 8, 2014.

{42} Meg McLagan, “Imagining Impact Documentary Film and the Production of Political Effects,” in Sensible Politics: The Visual Culture of Nongovernmental Activism, Meg McLagan and Yates McKee, eds. (New York: Zone Books, 2012), 305-19; Winston et. al., The Act of Documenting, 191-220.

{43} Ed Catmull with Amy Wallace, Creativity, Inc: Overcoming the Unseen Forces that Stand in the Way of True Inspiration (New York: Random House, 2014), 66.

{44} Richard Plepler, interviewed by CNN’s Dylan Byers, December 18, 2017, CNN Business, excerpt on CNN.com.

{45} Jonah Weiner, “The Great Race to Rule Streaming TV,” New York Times Magazine, July 10, 2019; Ben Fritz, The Big Picture: The Fight for the Future of Movies (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018); Tanya Zuk, ed., “Streaming Wars,” In Medias Res, May 4, 2020.MediaCommons Project.

{46} As scholars Derek Johnson, Derek Kompare, and Avi Santo describe, these managerial performances should be understood as sites of “cultural intermediation” in which companies communicate their values to their employees, peer organizations. Derek Johnson, Derek Kompare, and Avi Santo, “Introduction: Discourses, Dispositions, Tactics,” in Making Media Work: Cultures of Management in the Entertainment Industries, eds., Johnson et. al. (New York: NYU Press, 2014), 1–24.

{47} Leslie Goldberg, “Disney+ Unveils Robust Unscripted Slate Featuring Pair of Marvel Docuseries,” Hollywood Reporter, April 10, 2019; Christopher Anderson, Hollywood TV: The Studio System in the Fifties (Austin: University of Texas, 1994), 133–55. Robert Iger, The Ride of a Lifetime: Lessons Learned from 15 Years as CEO of the Walt Disney Company (New York: Random House, 2019), 189–202; J.P. Telotte, The Mouse Machine: Disney and Technology (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 96–116.

{48} Oprah Winfrey, quoted in Chaim Gartenberg, “Oprah Will Release Two Documentaries on Apple TV Plus Along With A New Book Club,” The Verge, March 25, 2019; Sandra Gonzalez, “Oprah Unveils Documentary Projects and Book Club for Apple,” CNN Entertainment, March 25, 2019; “Lesley Goldberg and Natalie Jarvey, “Inside Apple’s Long, Bumpy Road to Hollywood,” Hollywood Reporter, October 15, 2019.

{49} Cynthia Littleton and Daniel Holloway, “To The Max,” Variety, May 13, 2020, 28–33; Daniele Alcinii, “HBO’s Nancy Abraham, Lisa Heller to Replace Sheila Nevins,” Realscreen, December 19, 2017; Jillian Morgan, “HBO Max Greenlights Unscripted Series, Docs from CNN,” Realscreen, October 24, 2019.

{50} Svetla Turnin and Ezra Winton, “Introduction: Encounters With Documentary Activism,” in Screening Truth to Power: A Reader on Documentary Activism, eds. Turnin and Winton (Montreal: KataSoho, 2014), 21.

{51} Amy Hobby et. al. Distribution Advocates website.

{52} Reports from such institutions as UCLA and USC show the severe lack of women and people of color in the media industries (including the commercial streamers). As these reports tend to focus on fiction film and television, more research is needed with regards to documentary. The Center for Media and Social Impact at American University has conducted some valuable studies on nonfiction film festivals, awards, and labor. See, for example, Caty Borum Chattoo and William Harder’s State of the Documentary Field: 2018 Study of Documentary Professionals.

{53} Legislation and the courts could also have a role to play in checking the rapid growth of major media conglomerates and holding them accountable to the creative talent they employ and viewers who consume their products. Debates surrounding the legal frameworks for regulating big tech need to be placed in dialogue with other sectors of the film, television, and information industries. The FTC has an important responsibility in this regard as does anti-trust policy. David Sims, “Trump’s Justice Department Wants to Change the Movie Industry,” The Atlantic, November 20, 2019; Edmund Lee and Cecilia Kang, “US Loses Appeal Seeking to Block AT&T-Time Warner Merger,” February 26, 2019; Larry Downes, “On Internet Regulation, The FCC Goes Back to the Future,” Forbes, March 12, 2018; Rohit Chopra, “Dissenting Statement of Commissioner Rohit Chopra In re: Facebook Inc., Commission File No. 1823109”; Lina M Khan, “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,” Yale Law Journal 126, no. 3 (January 2017): 710–805.

{54} Patricia Zimmermann, Documentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and Politics (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019); William Uricchio and Katerina Cizek, Collective Wisdom Field Study: Co-Creating Media Within Communities, Across Disciplines and With Algorithms (MIT Co-Creation Studio, Open Documentary Lab, Cambridge, 2019); Eric Hynes, “Field of Vision: an Interview with Co-Creators,” September 9, 2015, Field of Vision website; Steven Zeitchik, “For Citizenfour director Laura Poitras, a bold new platform for documentary film,” Los Angeles Times, September 27, 2015; Third World Newsreel has begun partnering with Anthology Film Archives and Lightbox Film Center to host online screenings of both seminal works of radical cinema and new projects by underrepresented filmmakers; Films For Action is a nonprofit open-access video archive that offers over 40,000 documentaries curated by theme such as “Systemic Racism,” “Globalization,” and “Indigenous Issues.” Some media platforms have targeted educational institutions such as libraries and universities. Chris Cagle, “Kanopy: Not Just Like Netflix, and Not Free,” Quorum, Film Quarterly, May 23, 2019. Other platforms such as FilmStruck have already come and gone in the 2010s. David Sims, “The Demise of FilmStruck is Part of a Bigger Pattern,” The Atlantic, October 31, 2018.

{55} Cynthia Close, “OVID.tv, a New Online Distribution Collaborative, Is Set to Launch,” Documentary Magazine, March 15, 2019. Some independent filmmakers and collectives have chosen to pursue open-access video sharing platforms and homemade websites for distribution. This often affords groups the opportunity to work on more expansive, multi-part projects; for example, Chris Johnson’s installation and interactive website, Question Bridge: Black Males; UnionDocs’ and Elaine McMillion Sheldon’s respective I-doc projects, Living Los Sures and Hollow, or Helen De Michiel and Sophie

Constantinou’s web series, Lunch Love Community. Patricia R. Zimmermann and Helen De Michiel, Open Space New Media Documentary: A Toolkit for Theory and Practice (New York: Routledge, 2018), 44–48; Judith Aston, Sandra Gaudenzi, Mandy Rose, eds., I-Docs: The Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017).

{56} PBS CEO Paula Kerger, interviewed by Eric Johnson, Vox, April 15, 2019. Nieman Lab (connected to Harvard University’s Nieman Foundation), and Current (connected to American University’s School of Communication) have provided extensive coverage of PBS’s funding battles, infrastructural shifts, and investment in tech in recent years. Viewer data for PBS streaming and broadcast programming can be found in the Audience Insight Annual Report (available online), created in collaboration with PBS Business Intelligence.