Picking Up The Power: Tania Bruguera and Gregory Sholette in Conversation

Tania Bruguera and Gregory Sholette

Many of the writings that comprise this special issue of World Records were energized by new political challenges to art and media institutions. At museums and universities across the world, artists and activists have clamored for the redistribution of institutional wealth and power, organized art workers, and criticized the extractive tendencies of liberal culture. At this moment, a new line of questioning has opened up around private art institutions’ de facto investments in prison building, munitions sales, drug trafficking, even sexual predation—investments which are often obscured by conventional ideas about art’s autonomous, and thus innocent, relation to its production and reception.

Artists Tania Bruguera and Gregory Sholette have explored these questions for a long time, performing practical engagements in the public sphere and developing the field of institutional critique. They are both prominent theorists of social practice and documentation, providing key concepts for understanding the political complexities that drive art and media today.

Bruguera’s methods—including what she calls arte útil and arte de conducta—involve daring, site-specific interventions that aim to shock audience members into recognizing that they exist in a world with others. She has corralled art-goers by mounted police and invited workshop participants to break the law (circulating a tray of cocaine at an event in Colombia, for example). Much depends on her geographic location. In Cuba, where Bruguera was born and spent much of her life, her work has become a channel for public expression. Her Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt, or INSTAR, is a hub of workshops and conversations about art and community work in Havana. In the US and Europe, by contrast, where Bruguera has been celebrated as a leading figure in social practice and performance art, her intention is to challenge the anti-politics of neoliberal institutional culture.

Bruguera has stressed that her work contains a medial logic, sometimes proceeding via re-enactment, sometimes through contractual performance. In a text read aloud during her 2009 piece Self-Sabotage (in which she played Russian Roulette before a live audience), Bruguera asserted that political art should concern itself with “suggesting new structures of power activation” and “establishing mobile structures of observation.” José Luis Falconi offered this elaboration: “one looks at oneself and evaluates one’s conduct, and the work of art acts as a ‘proof’ of means of acting in reality. The ‘documentation’ of arte de conducta is not a photo or a video, for instance, but a change in behavior.” The work prompts us to ask how the idea of a shared, living document might contest media conventions—particularly those linked to the determinations of state and market.

Figure 1. Documentation of Tania Bruguera’s SELF-SABOTAGE (2009). Image courtesy of the

artist.

Figure 1. Documentation of Tania Bruguera’s SELF-SABOTAGE (2009). Image courtesy of the

artist.

Sholette’s work includes collaborations with groups like Political Art Documentation/Distortion and REPOhistory as well as direct action with Gulf Labor Coalition. In addition he has an extensive research practice, publishing two monographs on the subject of contemporary political and activist art, along with five anthologies on the topic. The first, Dark Matter: Activist Art in an Age of Enterprise Culture (2010), explores forms of collective creative labor that take place below the visible surface, yet which are essential for replicating the hierarchical structures of the mainstream art world itself. Scholette asks, “how does this glut of art and artistic practices serve the reproduction and maintenance of contemporary art as a symbolic and material phenomenon?” He goes on to argue that the potency of such dark matter, both as transgression and as commodity, comes from capital’s apparatus of “decentralized communication” and neoliberalism’s voracious extraction of value from sites far from the traditional workplace. Sholette points out that “digital networks have become simultaneously the very means through which this ghostly dark matter could ‘find itself’” and “part of capital’s expanding communication’s network.”

In Delirium and Resistance (2017), Sholette theorizes the perils of political art practice in the context of what he calls “bare art,” which makes plain art’s continuities with capital, media, production, and so on. Explaining the situation, he writes that “since contemporary art no longer has any meaningful contextual or formal limits, it is also no longer possible for any art practice to radically exceed or subvert the field’s existing boundaries or discursive framing.” Without such framing, the political potential of socially engaged art and media practices must be rethought via a parallel analysis of extant phenomena outside the work. Sholette’s activism and his positions as a CUNY professor and co-director of Social Practice Queens—a consortial MFA support platform based out of the Queens College and the Queens Museum—provide outlets for such reconstructive practice.

The editors invited Bruguera and Sholette to discuss an array of pressing questions having to do with the character of public life at this moment (and its differences and continuities across geographies), artistic and institutional responses to contemporary crises, documentation as a mode of relational practice, and pedagogies of art- and media-making. The conversation, which was recorded in November 2019, was prompted by the participants’ engagement in 2017 at INSTAR and thus makes some acknowledgement of Hannah Arendt’s attention to the idea of politics as a relational space “in between” subjects. We hope that by addressing these questions, this conversation can clarify the stakes of political art and its institutional formats.

—Nicholas Gamso

****

World Records

Let’s start with the space of appearance, which is one of the primary tropes that gets invoked when talking about politics and protest in the arts. Hannah Arendt compares political work to performance, saying, “just as the virtuosity of the performer, dancer, theatrical practitioner is dependent on the audience, action necessitates the presence of others in a politically organized space. Such a space is not to be taken for granted wherever men live in a community.” Arendt provides us with this idea of politics that emphasizes theatricality and relational form. What do you see as the challenges of doing this kind of work and how do you see these questions in your own practice? Do you see yourself as producing a political space within an overdetermined political context?

Tania Bruguera

My work is not so much about helping others, but about the process of awareness—how to be part of others, how to create awareness about the political space of being together. It’s almost this idea of how to recognize yourself in others. In my case specifically, I am very clearly trying to create a political space and a political situation in most of the things I do. Especially at INSTAR in Havana. We invite thirty or forty people to come to workshops. The police detain someone, so when there’s another workshop nobody comes because they are afraid. So we have to build it up again. We have this idea that civic education is a tool to transform political violence into building something. And this is not only about Cuba. We are using this as a paradigm, let’s say, for conversation. I feel that we try to build instead of destroying. I am interested not in critique; I am interested in showing it can happen. When I was in the Communist Youth, it was called critica consertiva—constructive criticism—so you basically stand in front of everyone and say I’m sorry. It was kind of Catholic: I’m sorry, and I’ll do better, and this is what I did wrong. I want to do the same with other civic and political institutions.

I’ve also lately been interested in the question: can institutions feel? Because they are a political body—there are people inside. We always talk about institutions like they are this kind of robotic system. There are people who make the institutions.

Figure 2. Set at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts for Tatlin’s WHISPER #6 (HAVANA VERSION), Tania Bruguera (2009). In the original version at the 2009 Havana Biennial, an open mic provided a platform for Cuban citizens to talk freely. Someone has to step up to the microphone to speak for the piece to be realized.

Figure 2. Set at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts for Tatlin’s WHISPER #6 (HAVANA VERSION), Tania Bruguera (2009). In the original version at the 2009 Havana Biennial, an open mic provided a platform for Cuban citizens to talk freely. Someone has to step up to the microphone to speak for the piece to be realized.

Gregory Sholette

It’s interesting in terms of Hannah Arendt because of the relation between labor and action. As I understand her, Arendt’s emphasis is clearly meant to be a critique of capitalism as much as a critique of Marxism in its classic sense. She places labor in a field of human forces in connection to oikos—the house, the economy—where base needs are taken care of. Meanwhile, the highest level transcending labor is Arendt’s idea of action, which has to come through politics, as opposed to primary needs. But I’ve always thought, maybe being a bit more of a Marxist, that you can’t really separate the economic from the political because capital interpolates the everyday so easily, and ever more thoroughly it seems today. Arendt has this tendency to set up an almost ideal Ancient Greek image of society, but still, someone’s going to have to take out the garbage. And we know, those many of us who have worked in collectives, we know that we all must take out the garbage at some point, while also creating the group website, participate in hours of meetings, generate posters and banners for actions, and it’s all that sort of everyday stuff of practical labor in the art collective’s household that actually makes things work. So I’m interested in that everydayness and how it relates to and informs political performance, theatricality, and agency.

TB

Since Trump has gotten into power, I have tried to do a piece about him and I cannot do it. I have a folder in my Google drive with hundreds of ideas and not one works. One thing that interests me is the idea of appropriating the timing of politics in the work. In Cuba it’s very clear. Other countries—meaning capitalist countries—have learned to disguise the oppression. It seems that the work of an artist in such countries is to try to deconstruct the way society is disguising this oppression, instead of actually confronting the oppression. It takes so much work to find out how they have hidden the stuff that is really damaging people. It’s like a double step in a way.

GS

Let’s not forget, though, that anti-democratic neo-authoritarianism is creeping into much of society, just think of Hungary, Poland, possibly Italy, but also Brazil and Colombia, as well as many developing countries.

Still, I wonder if the problem of doing a piece about Trump is because he’s like a fucking performance artist already. He is the ultimate expression of a certain avant-garde. He is a guy who goes into the White House and blows everything up all day every day, like a cheap version of Marinetti (can farce be even more ominous than tragedy?).

TB

Part of creating this political community is understanding the time of politics. In this case Trump is messing up the timing. Things are piling up in such a way that there is no time to make people sit down and process.

GS

We started with space, and we almost immediately went to time. So the problem is time, maybe, not space. Capitalism doesn’t, in my opinion, really produce anything spatially. It simply occupies the spaces that labor and people create. But this time problem is accelerating, pumping into a completely other anterior zone.

I actually had this idea to create a magazine that’s published in 2060. It’s referencing things that are happening between now and then. But the publication has been suppressed, so the only way to find out about it is through a sort of indirect footnote in this future journal that’s called Plastique.

TB

At the institute INSTAR—which is also a verb that means to incite others or to push others to do something—we make a little sign that says Happy 2028. Like we are already celebrating the new.

GS

We did address this question of the future. It was one of the questions I raised with your students. We thought, what’s Cuba going to be like in 30 years? And people did drawings and it was quite interesting, though most of the predictions were not optimistic at all.

Collectively created drawings by INSTAR participants during Gregory Sholette’s 2017 visit, The sketches respond to the question: What would you say to Cuba ten years from today?

WR

This leads to a question about what theorist Stephen Wright has called a 1:1 relationship or a double ontology, which I know has animated both your bodies of work. Arendt has this great term picking up the power in her writings on revolution. The idea is that power is enacted in concert with others always, but also, I think, that infrastructures and apparatuses and relationships can be turned around in some interesting way in order to create something new.

In Tania’s work, this seems related to the idea that participants embody institutional space, political power, even documentation by way of a certain kind of sharing. In Greg’s recent book Delirium and Resistance, he notes that these concepts pose a risk given that practical art activities, in denying the field of autonomy, can become seamlessly integrated into a landscape of power or a violent economy.

What is to be gained and lost by thinking with these concepts today? Should the aims of practical and useful art be revised or emboldened in response to the parasitic character of capitalism? Is this an instance in which the geographic context determines the political viability of the intervention?

GS

I think what I was driving at is that once art steps into the zone of the juridical system, it starts falling under all of the laws and political valences that every other system or institution already deals with. I think an example of this challenge is the art project that was known as Conflict Kitchen in Pittsburgh (2010–2017), serving what Michael Rakowitz had earlier described as enemy food from places such as Iran, Palestine, and North Korea. Let’s say hypothetically that someone got food poisoning from them, could the artists then defend themselves by responding, I’m sorry you didn’t like the art? And the twenty or so people who were working there at one point making meals —I don’t mean to critique this but to raise questions—were they performers or were they laborers? Around 2015, Conflict Kitchen’s staff began to unionize for a $15 minimum wage and eventually succeeded, before the project came to an end. So you have this zone in which—if art is going to be 1:1 as Wright has suggested—it also enters into a whole realm of practicalities and details that it had been excluded from for centuries when art was merely considered an autonomous practice (real or imaginary of course). And this art that falls to earth also raises all kinds of new problems regarding political agency and commodification, but it also raises new interesting possibilities of activism and resistance. Though capital may be subsuming all other forms of production it does not mean contradiction—inherent within capitalist relations—are excluded or resolved, quite the contrary: these tensions come to inhabit the very core of the system in a bare art world with 1:1 artworks.

TB

1:1 is something I try to do with almost all of my work. I think that art should work in reality as well. I have problems with the idea of art as pure representation. Art has lost the urgency that makes it needed.

Art has this promise, like the idea of the promise of the promise. With 1:1—and I think that arte de util is like this specifically—it delivers. In autonomous art you have this kind of never ending desire that never gets realized. In art de util, the work delivers the promise. It actually has a different kind of satisfaction. This idea of constant failure; for political art it’s complex.

GS

It’s pretty clear that Arendt is a Kantian when it comes to aesthetic experience, that is to say she understands aesthetics and politics as detached experiences that set the stage for the possibility of action, even if that is the type of freedom of thought that Kant thought was so important (and which of course informs the very notion of autonomous art). But there’s also the whole idea of dependent beauty that Kant talks about in the third Critique, which is closer, I think, to your idea of useful art, Tania. It’s not completely detached. It actually has a utility. But it isn’t not beautiful, it isn’t not aesthetic in some way. It still falls into that broader contemplative space.

I like Wright’s 1:1 very much, but let’s not forget he also allows for the curious escape mechanism of what he calls a “trap door.” I love this part even more. It’s like yes—art can step out into the world and it can become truly non-representational, to the point where we no longer know that it’s art (the house painter who is really painting, etc.). It’s anything but what it would be as art, and it is what it is. But Wright always deploys this Duchampian idea of the “infra-thin” as if art has entered a non-Euclidean geometry with a little hidden exit. And I wonder about that too in this world we inhabit now. Once you completely eliminate the mediation and mimicry of representation, and you flatten art into a space that now must compete with the everyday world, then something is gained and something lost. I call this “bare art,” borrowing from Agamben’s idea of bare life, and believe that we’re now operating in a “bare art world.” All mystique is stripped away, though this is not completely negative because it opens up new possibilities and puts art directly into the game—as you’ve done Tania so clearly with INSTAR—with the everyday world and its politics. But bare art also sheds the ability to give people that breather, that liberating space in which you gain the time back capital has commodified. Ultimately, we have to recognize that art is not immune to all these contradictions that are in that world. 1:1 art underscores that tough love.

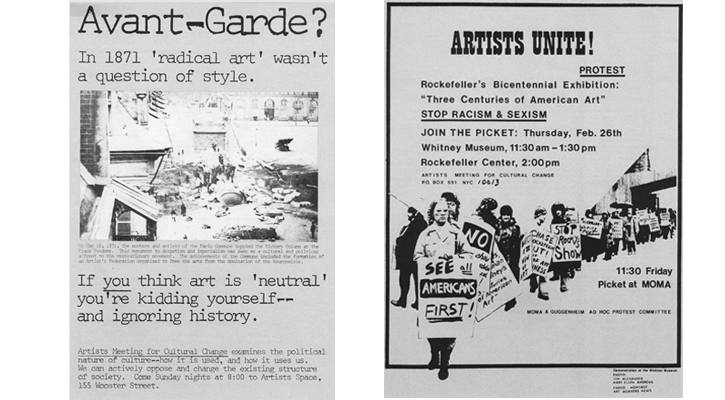

Cofounded by Greg Sholette, the artists’ collective PAD/D or Political Art Documentation and Distribution (1980-1986) aimed “to provide artists with an organized relationship to society, to demonstrate the political effectiveness of image making, and to provide a framework within which progressive artists can discuss and develop alternatives to the mainstream art system.”

TB

I also think there is another element to this, which is the idea of gatekeepers and the frame. We are dealing with this frame of the work—like framing something—and then have the gatekeepers who authorize, or not, people to enter that frame. One thing I think is a political gesture is to not eliminate the gatekeepers, because of course people will say it’s impossible, but at least to create several dimensions of the framework so you have so many gatekeepers that you actually create no gatekeepers—you know what I mean?

We are living in a world of art where the gatekeepers are becoming very limited and therefore very powerful. So there is almost an authoritarianism where if you don’t do certain things you cannot access the legitimacy of the institution or of the money or whatever. If you are a political artist, you have to fight the art world.

GS

The irony too is that in a sense the free market of ideas and practices, which has always been and remains the ideological core of the bourgeoisie with regard to capitalism, is that everybody can come and sell their labor equally in the marketplace, meaning that there is allegedly no prejudice, no racism or sexism, etc. Part of this is nonsense. This is one of the ironies of the art world in so far as it is absolutely the last place that we find a free market. The art world more accurately represents the false free market of neoliberalism, because it is overflowing with all kinds of asymmetries and power structures. How do we create a kind of alternative art un-world that doesn’t then draw on that libertarian idea of everybody is just going to put the goods out for everyone else to see and it’s just that simple. This is one challenge.

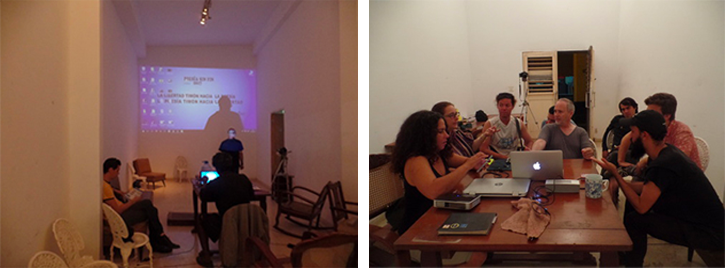

But I think it’s interesting when you talk about the framing. You’ll have to tell me if this is true of your experience in Cuba, Tania—given that you are not considered an artist by the Cuban authorities. We might say that they’ve unframed you. To them, as I discovered on my visit to the Institute in 2017, you are considered an activist, a politician, whatever, but you’re not an artist. Whereas here in the US or in Europe or other zones where the art world thrives, you are one of those artists who go directly after the frame and try to rip that frame away from the very division between art and politics and activism. I find that contrast very interesting and indicative of the time we live in.

Figure 3. Gregory Sholette (center) visiting the Hannah Arendt Institute of Art (INSTAR), founded by Tania Bruguera (second from left), in Havana, December 2017. Photos courtesy of Gregory Sholette.

Figure 3. Gregory Sholette (center) visiting the Hannah Arendt Institute of Art (INSTAR), founded by Tania Bruguera (second from left), in Havana, December 2017. Photos courtesy of Gregory Sholette.

TB

When they took the frame away in Cuba it was ironic—it was like yes, I finally succeeded, but then I realized that they took it away so that they could apply the law they use for traitors. If you remove the element of art, with which it is your right to have your own perception of things, you become a traitor.

I never said I’m an artist louder than this.

I always say that I use the art world. And I think it’s ok—they use us as well. Because when the government removed that frame and said I’m a traitor, not an artist, what I did was respond by saying yes to the Venice Biennial. I personally had no interest at all—sorry—to be part of the Biennial. It’s a structure that for a long time I had no interest in. But I had to say yes because it helped me. I needed to use the Venice Biennial to say I’m back in the frame.

I think we should do it more. Because the art world uses artists, so we should start using it, politically speaking. I think people use it, but for personal gain and the career thing. You need to start using it for politics.

GS

Something that always comes up with people who consider themselves community artists or social movement artists is that they don’t want to have anything to do with the art world and they often denounce it as corrupt. And I say to them, well then why do you even care enough about it to denounce it? My guess is that despite all else they recognize that the frame has some value which you can leverage. It’s tricky though, because as you’ve found out in Cuba, Tania, you have to understand the particular context in order to leverage its power.

TB

I never want to disengage the art world, you know, and it is because it puts you also in a very good position because, if you do socially engaged art, you don’t have to use the same scarce resources that activists have. It creates a different lens. You are not competing with activists, you are not saying you are better than them for a grant.

With art you can do what you cannot do as a citizen. There is a space of trust, even in chaos—they trust that you know what you’re doing, even if we don’t know what we’re doing. There’s this respect for culture. People may not understand exactly what it is, but they know that culture is important, so they understand there is something. Maybe it’s this idea that art is always seen as something for the future, like in the future it’ll be seen as amazing, looking back.

GS

I think the biggest challenge is that the gatekeepers are fewer and fewer and increasingly concentrating and monopolizing the actual and symbolic cultural power of contemporary art. How then do you wrest away even a portion of that power and, harder still, redistribute it? That’s the key, right? Distributing it beyond what the gatekeepers would ever want you to go?

TB

I heard of someone who was contacted through their gallery to do a project in public space in a city, a permanent project, and the gallery said no, this person is not going to do it. They didn’t even inform the artist. What my friend told me was that they were interested in having the artist produce something the gallery could sell, instead of doing something it would not benefit from. That’s the state of capitalism in the arts at the moment. I also talked to a friend of mine who is a curator and he was complaining about how much the galleries are pushing to have the artists in the museum.

GS

This is why I use the term “bare art,” because I feel like a lot of those older, slightly aristocratic ideas have now just been swept away and we’re facing the raw situation of a demystified art today. It’s kind of ironic because in a way, I sense we want to bring back some of that respectability back to art as a type of non-capitalist labor and a realm of sensual freedom, but to do so in a political way or in a strategic way, without regressing back to a period in which art was only for elites.

Today, as we witness the expanding unionization drives by museum workers, there appears to be an ask in play that goes well beyond even the things that the Art Workers Coalition (AWC) tried to do in the late ’60s and early ’70s. AWC sought respect and compensation and power for artists as a type of laborer who the museum depended upon for its very meaning. Now I think there’s a real question regarding the entire structure of the art world when cultural activists—both inside the institutions and within the art community generally—demand a de-toxification of museum boards, or the rejection of tainted capital by Sackler pharmaceutical family members, or when the idea of decolonizing the museum is proposed. So while this is a repetition of the post-1968 cultural revolution, it’s also a very different moment as well, and much more challenging I think. Then, with some important exceptions such as Guerilla Art Action Group and Black Mask perhaps, artists wanted to reform their relationship to the institution. The very idea of institutional critique grows from this impulse (and yet we see how institutions have managed to re-absorb that opposition, generating an entire genre of artistic practice). Today the very structure of our bare art world is under review and facing fundamental resistance if not rejection.

Figure 4. Pages from an Anti-Catalog, produced by Artists Meeting for Cultural Change (1977). Courtesy of Sholette Archives.

Figure 4. Pages from an Anti-Catalog, produced by Artists Meeting for Cultural Change (1977). Courtesy of Sholette Archives.

TB

It’s more Hans Haacke. You almost feel like everyone applied the Hans Haacke methodology to reality.

GS

It’s also interesting that so many of the people who are creating labor unions in museums or who are trying to, most recently at the private Marciano Foundation in San Francisco, many if not the majority of them are younger people who studied art, perhaps with people like me or maybe Hans Haacke or other artists knowledgeable about institutional critique. Now, as actual employees of art institutions, they’re enacting this same practice, but not as an artistic project per se, rather as the very reality of their relationships with institutions as workers. It’s as if institutional critique has now come home to roost.

WR

And in education?

TB

I also think that the younger and younger generations have this kind of anxiety or desperation because they have to pay their loans for the university (in the US I mean). When I was a student, we had a different understanding of the process of being successful. And the concept was, you are successful when your peers—not the institution—respect your work. Success is when you have people, who are artists like you or critics who are amazed by what you do and excited about what you do. Now I think it has shifted into a kind of an institutionalization. People almost feel like the only legitimacy is the one given by the institution.

GS

Or legitimacy granted by the art market. And what you’re describing, Tania, has accelerated to such a degree that we know certain art programs (which we won’t name here) allow critics and curators to visit their students’ studios even before they’re graduated in order to select work for purchase or for exhibiting. It’s a bald-faced submission of education to the market and to our bare art world. And what about student debt? When I was an undergraduate I lived in a city (New York in the late 1970s) where you could rent a place with five rooms for a few hundred dollars. You could receive a modest grant, and you could maybe teach one adjunct class and get by. That is not possible anymore. And not just in New York, but in any of the major cities around the world. So it is a very different landscape that most young people confront.

I teach at a public school (CUNY), and of course it’s cheaper than other schools, but it’s still a lot of money for working class people. Let’s face it, twelve thousand dollars is really more of an expense for low-income people than one hundred thousand dollars is to an upper-middle class person. There’s a whole scaling-up of one’s relation to both financial and cultural capital based on class background, with those who are more connected always capable of extracting more value from a degree than those who are not.

At Queens College our Social Practice Queens (SPQ) initiative was started in part when Tania was invited to work with us by Queens Museum director Tom Finkelpearl (this was in 2010, before he became New York Arts Commissioner). Our approach is to encourage artists to envision their work—whether it’s performance or community research or even making welded steel sculpture—into a kind of social action. But we also examine the art market, coldly, critically, by looking at the debt structure, and that can frankly be very depressing, especially to younger artists (some have shed tears). Still, it seems that one is better off actually seeing things for the way they are and then finding the ways you can oppose that condition. In other words, don’t go into the scene blindfolded.

EXTENDED PLAY. From “Immigrant Movement International,” Tania Bruguera (2015). Courtesy of Art21.

TB

I think Cuba is like a hyper-institutionalization case. If you are an alternative artist or if you like independent art, they don’t recognize it because they want you to be linked to institutions they recognize. If you go to these kinds of underground institutions, which are smaller scale, more challenging, more avant-garde, they don’t recognize your work.

GS

It’s also kind of exciting—we don’t have that kind of space in New York or the United States. I mean you can do anything the fuck you want and you know nobody’s going to care, or almost nobody. I think if you blew up the art economy that would really upset things. But short of that, there are probably few things anyone in the cultural sector would really find deeply problematic. In terms of the content of one’s work almost anything can be shown. We are truly post-art-scandal. And as I mentioned earlier, with the man in the White House behaving as an avant-garde radical what else is possible? A revolutionary middle?

WR

There are renewed questions about whether liberalism will be sustained in Cuba. Decree 349, which puts restrictions on artistic speech, seems similarly poised to shatter the myth that Cuba is poised for normative integration. What is the status of this decree and what does it portend for the future of art in Cuba? Is there a relationship between the decree and Havana’s recent status as major art center (a direct relation or one we might infer)?

TB

349 is a legal tool for the government to exercise censorship. Before everyone knew what the limits were, they were invisible but everyone saw them. Now they legally can take away your house, your whatever, for doing what is not authorized by the government as cultural activity, which actually contradicts the constitution where it says that “culture belongs to everybody.” But if you cannot do a cultural event or show other people’s culture, how is it for everybody?

WR

Is there a way to have the good things about liberalism without the bad things?

TB

I think it should be possible. I almost feel like in socialism you lose your individual rights in order to have collective rights and in capitalism you relinquish the possibility of having collective rights in order to have your personal rights. And neither is working. I almost feel like it would be amazing to live in a society where you have the kind of ethical proposal that socialism has with the right to your individuality—the right to challenge systems—that you have in capitalism. It almost becomes blackmail: oh you have your education so shut up. No, why should I shut up?

It almost feels like the way to succeed in protesting in the arts in the US is to make it economically disadvantageous. It costs more for them to clean their image than for them to do the right thing.

GS

This goes back to your point about feelings—can you hurt the institution’s feelings? Maybe not, you can only hurt its bank account.

WR

In the US context, art is essentially a sector of the economy, but this provides the groundwork for groups to come in protest.

TB

The best work that is done today is work that shows the injustice of the art system. Maybe this is because people don’t feel it is artwork. It is something everyone else can relate to. If you are a bartender you see this happening with the artists and you say, that is what’s happening with me. At the same time it’s hard because institutions like showing art that is political, but they don’t want the artist to be political with the institution. That’s a big contradiction we have right now. People invite me . . . I love your work, why don’t you come to the institution and do something. Then as soon as I propose something, they say not here.

If you are doing art about justice for immigrants and then you demand as part of your project an ethical aspect—that the institution has to perform some kind of justice—they don’t like it. It is a contradiction because they want to show the work, but they don’t want to activate the politics that make the work ethical.

REPO History, signs from LOWER MANHATTAN SIGN PROJECT (1992) and QUEER SPACES SIGN PROJECT (1994), photo-silkcreened on aluminum panels. 18”x24” Photos courtesy of REPOhistory.

WR

We’re interested in your work as a documentarian as part of place-based doc collectives in New York.

GS

We could begin with Political Art Documentation/Distribution that was co-founded with Lucy Lippard, Jerry Kerns, and many other people in 1980. That was when of course there was no internet, yet we were literally trying to create an distributable archive that would inspire people to create similar socially engaged and political art practices. Remember, this was a time in Europe and the US when, as the late Tim Rollins used to say, the idea of political art was typically thought of as “charcoal drawings of Lenin” and similar forms of socialist realism. That is not what PAD/D, or our kindred New York collective Group Material imagined it was doing. So the PAD/D Archive—now located at the Museum of Modern Art (not without irony)—sought to show that there are all kinds of possibilities for engaged art, and we can show you what that means. Thus documentation was meant to be a living, educational tool.

Then of course in the 1990s with the collective REPOhistory, we collectively put the archive into the street, installing metal signs that informed passersby about histories either people didn’t know about, or events that were forgotten or suppressed. It wasn’t like we were trying to establish a different history. To my mind at least, REPOhistory was showing what’s always missing from the record of history, a certain archival supplement that makes the possibility of total documentation impossible. So instead, let’s talk about history as a kind of endless process that everyone has access to, rather than a privileged process of documenting the past. This is what I take Derrida to mean by archive fever.

TB

I still think art is a great documentary sphere because you are looking at yourself while you are doing it so you have a critical eye simultaneously with the action that you are doing. I think that’s pretty special.

Recently I was in Manchester working on a project and heard that the Manchester Museum is giving some artifacts back to the Aboriginal people in Australia. What is interesting is that, because these were ceremonial objects, some Aboriginal people came to treat them properly for transportation. They were asked, where are you going to put them now?; and the answer was we are going to bury them because they belong buried. I think the biggest transformation will be when people start to understand the work not through the eyes of the European gaze but through each people’s cultural gaze. We’re still not there yet.

It almost feels like the process to be accepted is whitening yourself and westernizing yourself. This is something that happened when I was at School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I started creating my own words in Spanish to explain my work (and now I have seven or eight or whatever, e.g. Arte de util) and that was an artwork. I didn’t start thinking about it at the beginning but now I understand it’s an artwork.

GS

Is that why I could never understand what you were saying when I ran into you at school?

TB

Exactly! This idea of not understanding was so important. The problem is that it almost feels like the Western European canon thinks it always understands. We need to start a culture of I don’t understand.

GS

It’s an interesting moment. Gulf Labor, Decolonize–

TB

One has to be careful about self-satisfaction. Because, for example with decolonizing, something has happened. It’s become popular. It is a very clear movement, let’s say, and therefore it has been accepted quickly, which is great and it has made a lot of change. But at the same time, we have to exercise our demands in such a way that they never lose their friction. Because a lot of people I’ve seen all over the world now say oh, we are decolonizing—but when you look at what they’re doing, they’re just saying it. So the art world and capitalism have an amazing capacity to empty out content, or empty out agency.

When we talked before about can the institution feel? That was kind of the question I was asking the Tate when I did a project there. And also the question of how you can be so influential in the art world but not to your neighbors. That’s another paradox we’re living in the arts. The idea of pretending to be for everybody—names, numbers, numbers, numbers—but maybe it’s for tourists, not the people next door. It feels that this idea of how can we generate not populism in art but a conscientious effort to open the institutions again.

When I did the Tate Neighbors, something happened—people liked the name and so Tate immediately —you know, has different museums, there are like five—they all said, we want to have Tate Neighbors here. And I said no. Because artists have to have some control. This is a capitalist conception of art where you just do franchises. I’m not saying they should not have it, but I say that each of you have to have your own model of what works. This is another thing we have to battle in a way, making sure the work doesn’t dissolve in the idea of the happy feeling.

Background Video: Immigrant Movement International: Year One (Creative Time, 2017)