Can injustice be answered by catharsis? In other words, is catharsis—rooted in the Greek word kathairein, meaning “to cleanse” or “to purge”—itself just, and thus a right? The systemic answer to this question is clearly no; emotional release or psychic satisfaction would seem to bear little to no relationship to the organization of power inequities and the violences they encourage or enable, even at the level of person-to-person harm. But what about as a matter of narrative? Is emotional truth-telling, the purging of psychological toxins, or release at the level of feeling a socially productive need that discursive action—whether in the real spaces of life or the mediated scenes of our cultural artifacts—can offer as meaningful rejoinder to the traumas of the world?{1} After all, we are all subject to human emotions, and the pain of being rendered vulnerable to injustice is real, so that—as feminism has taught us most directly—what gets experienced as personal is often symptomatic and expressive of the political.{2} So why not catharsis as a demand and a right?

For the past few years I’ve been teaching a small undergraduate seminar on the politics of prison and abolition cinema. Over the course of twelve weeks I share a range of work with my seminar students: experimental videos, Hollywood fictions, documentaries whose subjects veer far from any direct engagement with prisons or policing, and even a visceral, deeply challenging documentary feature about a community of registered sex offenders, some of whom admit to the most horrendous and upsetting of acts. The students, across multiple iterations of this class, have been lively and engaged, down to debate the hard stuff and mostly unfazed by an abolitionist framing that asks them to imagine a world without carceral punishment. Except, that is, in the case of one film, a documentary titled The Recall: Reframed (Rebecca Richman Cohen, 2018), which I recently taught for the first time. It’s a short and formally straightforward documentary, but it caused a minor rebellion. And insofar as that rebellion involved a mixture of pain, anger, and frustration from my students, it provoked the question driving this essay: How does catharsis—and our presumed right to attain it—operate in Western, neoliberal culture as an affective currency that connects our screens to our courts in the reproduction of a carceral common sense?

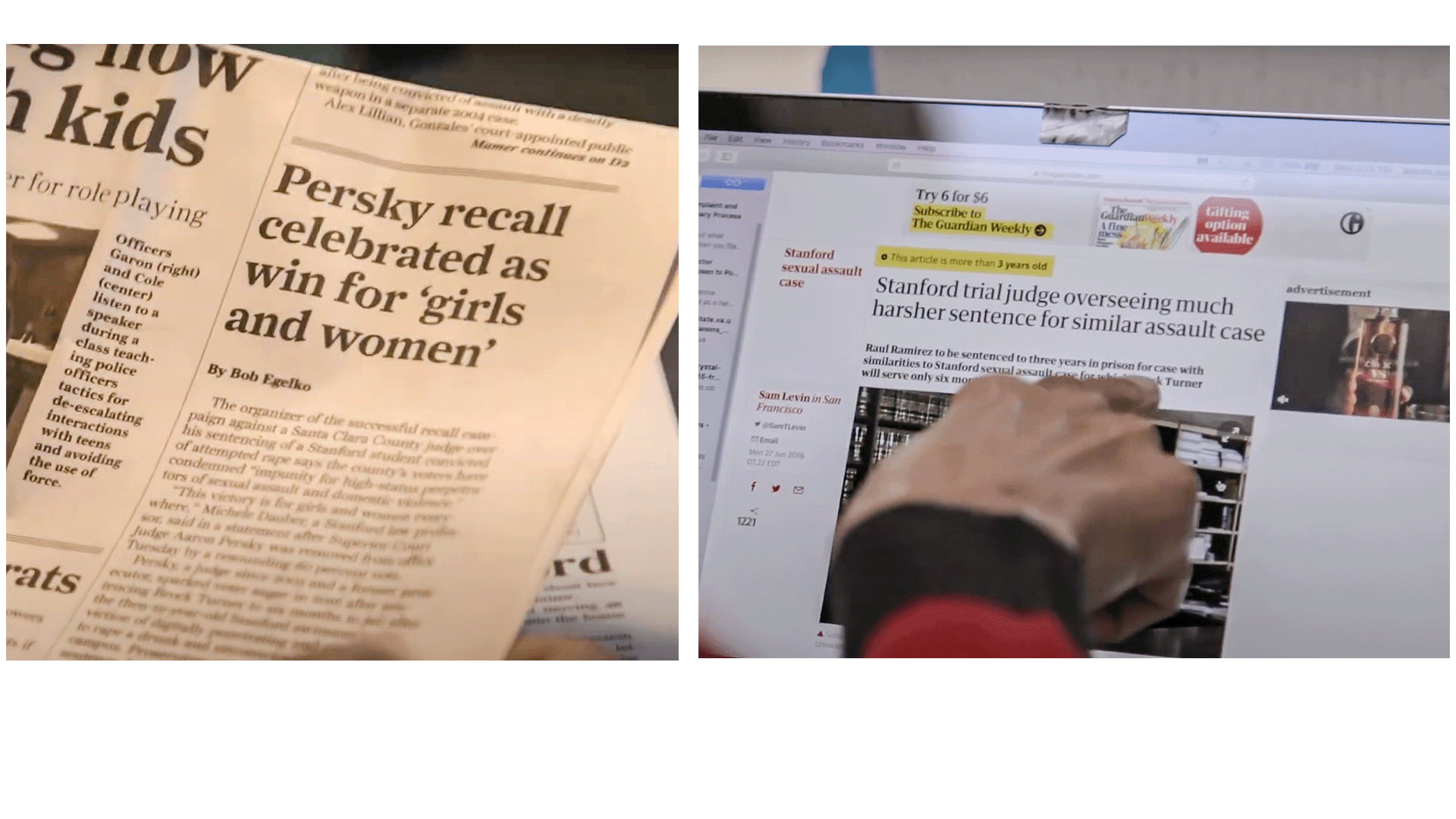

Running a tight nineteen minutes and broadcast on the major news network MSNBC, The Recall: Reframed examines the 2018 recall of California Judge Aaron Persky, who caused a well-publicized uproar among advocates for survivors of sexual violence when he handed down a sentence deemed too lenient to a white college student convicted of sexually assaulting a fellow undergraduate. In the aftermath of that controversial sentencing, a coalition of advocacy groups ran a contentious and highly public political recall campaign on the grounds that, as one leader of the campaign says in the film, “We need judges who understand sexual assault and domestic violence.” The campaign was successful, and Persky lost his judgeship.{3}

This recall, the film argues, was itself a miscarriage of justice, and more crucially an expression of misplaced progressive and feminist umbrage whose consequences would be borne most acutely by less privileged black and brown sexual assault defendants. As one legal scholar in the film puts it, “People widely recognize that women who have been victimized by men have not received justice. . . . But criminal law doesn’t equalize the world. It does the opposite.” My students largely agreed, week after week, with this logic. But when they were asked to hold this logic alongside the feelings of frustration and disappointment stirred up by this particular case, and perhaps also by the mode of the film (sober, rational, driven by talking-head experts, and designed to have immediate policy impact), the students took exception.

The details of the original case go like this: In 2015 Brock Turner, a nineteen-year-old elite student athlete at Stanford University, was charged with sexually assaulting fellow Stanford student Chanel Miller. After a night of drinking, Turner was found having sex with Miller’s unconscious body next to a dumpster outside of a fraternity party. Turner was arrested and tried, and ultimately convicted of three felony counts of sexual assault.{4} In 2016, the Santa Clara County Superior Court judge presiding over the case, Judge Aaron Persky, sentenced Turner to six months in county jail, of which he served three. In the charged public sphere in which this trial was also playing out, the sentence was deemed extremely lenient, on its own terms but especially relative to the sentences typically given to the vast majority of defendants (many of them poor and racialized) convicted of the same crime.{5}

The circumstances of the case were widely reported and debated, owing in no small part to the courageous activism of the survivor, who read a widely circulated victim impact statement during the trial in which she addressed her assailant directly, saying, “You don’t know me, but you’ve been inside of me, and that’s why we’re here today.”{6} This was also the moment of the #MeToo “reckoning” in the United States, and it was inevitable that the trial would be swept into the strong feelings that movement generated. Everyone, it seemed, was paying attention to sexual assault cases, especially those involving powerful or seemingly privileged men, and everyone was poised to point to these cases as evidence of either the failure or the success of feminists’ demands on society to take sexualized violence seriously.

The Recall wasn’t on my original syllabus. I included it only after I noticed students name-dropping the Brock Turner case as a placeholder for the racial and class inequities they recognized as endemic to the criminal legal system. Their concern, rightfully, was with the ways in which increasingly long sentences for violent crimes operate alongside mass criminalization of nonviolent crimes to uphold an unequal social order, and to express the inherent racism and classism of the prison system. These reasons, among others, said my students, are why the prison system should be abolished.

But when I showed them The Recall, instead of computing the film’s argument as a continuation of their own critical analysis, some of my students felt angry. In a class with a clear feminist, antiracist ideological slant, this was a disconcerting film, one the students felt, affectively, was violating these principles even while in its argument and analysis it was upholding them. That the film itself offered an abolitionist critique of the recall process against Judge Persky was beside the point: Abolition is about siding with the powerless, not the powerful, and this case had proven that the law was still on the side of the powerful.

The anger was one of frustration. The film’s narrative was experienced as more than dissatisfying, but as actually stymieing something necessary to the justice-seeking viewer. By showing the film, one student said to me, I had “robbed” her of a crucial, visceral emotional experience that she felt a right to. “I am the same age as Chanel Miller was when she was raped,” she said. “I know so many people and so many friends who have been assaulted on campus.” The film’s sober and intellectual, even legalistic, analysis and aesthetic left no room for righteous feeling or emotional release.

Excerpt from THE RECALL: REFRAMED (Rebecca Richman Cohen, 2018).

The prison abolitionist organizers Mariame Kaba and Rachel Herzing have addressed similar calls for punitive accountability in their own writing, remaining unequivocal about the irrelevance of feeling to a material politics of abolition. “Advocating for someone’s imprisonment is not abolitionist,” they argue. “Mistaking emotional satisfaction for justice is also not abolitionist.”{7} And while I, too, was tempted to title this essay “Fuck Your Feelings,” the aftermath of this class screening has nagged at me. What accounts for the anger felt by my students after the viewing of The Recall? One speculation is that it emerged out of a basic contradiction that has no easy settlement: the difficulty of a critical and even antagonistic (which is to say, abolitionist) analysis of carceral policies and logics coexisting with the desire—which we might qualify as a feminist desire—for relief from, or remedy to, the pain of traumas incurred by patriarchal culture. That this desire has been in recent decades sutured in common sense to the outcomes of criminal legal proceedings, and the various theaters in which that suturing has been ritualized into inevitability, is what interests me. The critical analytic position does not negate the latter affective experience. But in the absence of meaningful critical attention at the register of the affective, those desires are available for capture and redirection by all sorts of interests that are at odds with the struggle to eradicate gender-based violence or to achieve a social justice more broadly.

Indeed, our contemporary media landscape is awash in narratives that frame carceral punishment as a means—indeed the only means—of vindicating the suffering of survivors. Wherever the promise of catharsis constitutes the only achievable form of justice, our cultural and narrative forms do the ideological work of the carceral state by harnessing legitimate feminist grievances to punitive demands. To make sense of how we’ve come to this expectation for catharsis, it is useful to begin not with cinema at all, but with the history of the victims’ rights movement and its demands.

****

Carceral Feminism and the Victim Figure

Critical scholars of the carceral state have charted the ways in which the emotions of particular populations have been captured, even amplified, by powerful agents with vested interests in the growth of carceral institutions, even as complex affective needs are left unaddressed by our criminal legal system. This is, in fact, a point made by one of the main interview subjects of The Recall, feminist legal scholar and former public defender Aya Gruber. Gruber’s book The Feminist War on Crime offers a convincing case that the impulse of many feminists (and nonfeminists) to demand harsher punishments for sexual crimes has resulted in them becoming “soldiers in the war on crime . . . expanding the power of police and prosecutors.”{8}

What Gruber is describing is a phenomenon dubbed by many critical prison scholars as “carceral feminism.”{9} Carceral feminism describes the historic and systematic congealing of feminist and women’s rights advocacy with interests and policies that help build up, rather than dismantle, the carceral state (the term used for the expansion of state investments in policing and prisons). The retributive “impulse to punish,” where punishment is seen as synonymous with justice, is itself a historical and material phenomenon, in no way inherent to feminist anger or even longings, but something produced as a kind of feminist common sense in some places and at some moments in concert with political realignments that continue to shape feminist wants today.{10} Many abolitionist feminists trace these active alignments to the 1970s and the antiviolence movement central to the organizing of many American feminists and women’s liberation organizations.

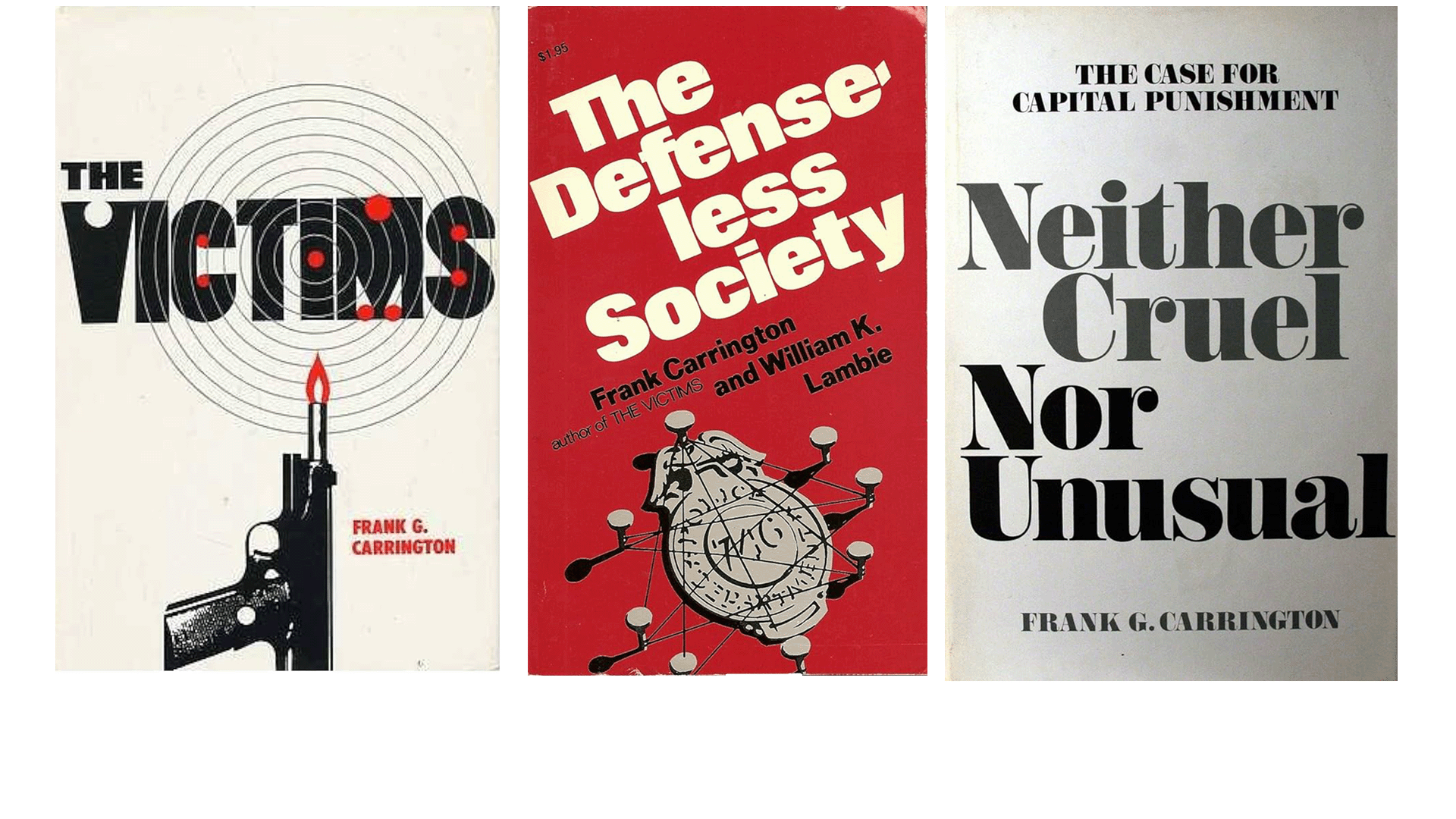

In 1975 a lawyer named Frank G. Carrington published a book titled The Victims with the support of conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation. Almost a decade previous, Carrington had founded a group called Americans for Effective Law Enforcement as a vehicle through which to challenge due-process provisions that protected the rights of defendants. Carrington was a law-and-order conservative and was part of a growing chorus of influential thinkers and politicians, including California Governor Ronald Reagan, that in the late 1960s and 1970s campaigned on the argument that the country and its courts were too soft on crime.{11} To mobilize support for this position, Carrington and others alighted upon the figure of the victim as a putatively underrepresented and undervalued protagonist in existing criminal justice discourse, and sought to justify desired tough-on-crime policies by centering victims—actual and fictitious—in their rhetoric and activism.

This was the existing discourse that the growing feminist movement of the 1970s entered into, and eventually joined forces with. Forged out of an uneasy coalition between liberal feminists and the US conservative right, the victims’ rights movement has in recent years achieved unprecedented influence within Western criminal legal proceedings. From a feminist perspective, victims (or survivors) of sexual violence, domestic abuse, and other gender-specific harms were very clearly given second-class standing within existing laws, policing practices, and criminal justice proceedings. Alongside the knowledge gained by survivors from personal experience, there’s a great deal of data that supports this claim. Compared to other violent crimes, sexual assault and domestic violence cases are underreported by on-scene police officers, rarely result in arrest, and face steeper barriers to prosecution and conviction.{12} As criminologist Melissa Morabito and her colleagues April Pattavina and Linda Williams demonstrate in their review of the literature, when officers doubt the victim’s credibility (citing supposedly extenuating factors such as drug addiction, mental illness, or employment as a sex worker) they are unlikely to report the assault.{13} Bias at a variety of levels of the law, in concert with pernicious patriarchal myths, has undermined women’s rights by suggesting, for example, that married women cannot be raped, or that a woman can be deemed at fault for her own sexual assault on the basis of her dress, previous sexual activity, or consumption of alcohol.

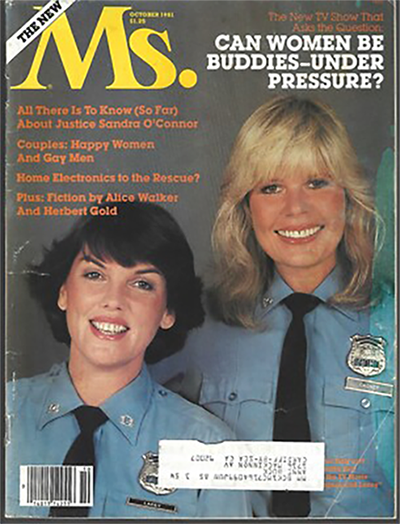

In the realm of popular culture, the merger of conservative tough-on-crime rhetoric with the feminist movement to recognize historically ignored violence against women found a ready outlet in the television police procedural, itself overdue for a “feminist” reckoning. As reality television scholar Laurie Ouellette has discussed in depth, the 1980s and 1990s were key decades in the consolidation of the heroic policewoman onscreen, as feminist scholars and popular feminist magazines such as Ms. and Bitch cheered on the rise of the TV female cop and plotlines now centering “women’s issues,” especially those underscoring the perceived epidemic of sexual violence. Later, broadcast series like Law & Order: SVU, a wildly popular television show that debuted on NBC in 1999 and continues to air today, brought mainstream visibility to a figure that feminists had been attempting to center in public discourse since the 1970s: the “sex crime” victim.{14}

Officially giving language to the ways in which survivors of gender-based violence have been failed by the legal institutions of the state proved a powerful way for the incipient victims’ rights movement to channel much-needed public and philanthropic aid and resources toward vulnerable women. It also seemed to signal a concrete antidote to the biases marshaled against women in their quest for legal accountability. The language of victims’ rights thus “marked a shift from a crime model of victimization that often disappeared the victim, to a trauma model that amplified the voices of victims and the affective dimensions crime had on the family.”{15} Women were no longer to be abstract ideological sponges in the scene of justice, absorbing misogynistic mythologies about “asking for it.” Through the category of the victim and the language of rights, advocates argued, survivors would finally be taken seriously under the law, their on-the-record testimonies evidencing, at last, some legal and cultural recognition of their pain, and through this pain, their personhood.

In the 1970s many second-wave feminists began making domestic and sexual violence against women their primary issue in the broader movement for gender equality. To achieve its goals, the movement partnered with some unlikely groups to appropriate the existing resources and tactics of the carceral arm of the state. The political scientist Marie Gottschalk traces, for example, how the US anti-rape movement began in the 1980s to play the crime card in order to attract state resources for rape crisis centers. They partnered with organizations like the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), a group with little connection to the feminist movement and few qualms about taking funds from pro-punishment units like California’s Office of Criminal Justice Planning.{16} One legal reform won by these new coalitions was the implementation of laws and policies that would require police to make an arrest in all cases of domestic violence, even if the arrest went against the wishes of the victim.

MS. magazine cover, October 1981, featuring Tyne Daly and Loretta Swit in CAGNEY & LACEY (1981–88), billed as the first female buddy cop TV series.

MS. magazine cover, October 1981, featuring Tyne Daly and Loretta Swit in CAGNEY & LACEY (1981–88), billed as the first female buddy cop TV series.

To make such alliances, many feminist groups leaned into narratives that scripted survivors as victims in need of state intervention. “Feminists’ ideal victims,” writes Gruber, “thus looked quite similar to the victims imagined by conservative politicians. Both were innocent, anguished, preoccupied with the crime that occurred, and desirous of punishment as justice. Moreover, feminists’ reliance on trauma to explain imperfect victim behavior resonated with sexist cultural stereotypes about hysterical or cognitively defective abused women and ruined rape victims.”{17} Partly to counter such stereotypes, the antiviolence and victims’ rights movements of the 1970s introduced a new component into the American criminal legal system that would come, over the next half century, to play a significant role in sentencing as well as in the culture at large: the victim impact statement.

****

Listening to Victim Impact Statements

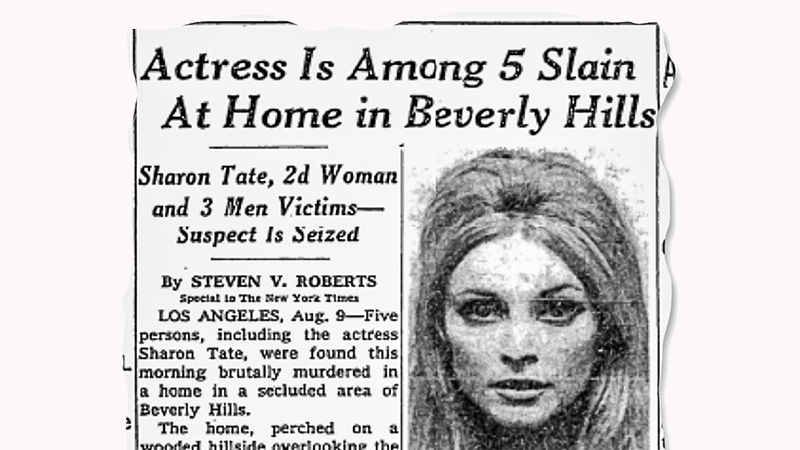

The first victim impact statement in the United States was read in 1976 by Doris Tate, the mother of Sharon Tate, one of the Manson Family’s murder victims.{18} The fact that Sharon Tate was a glamorous Hollywood actress and the Manson murders a globally broadcast object of public fascination surely factored into calculations around the role of audience, and the function of storytelling, during the criminal trial.

Envisioned as an opportunity for victims to express in their own words the emotional, physical, and financial impact experienced by them and those close to them as a result of the crime, impact statements assist in helping the judge to determine a sentence for the perpetrator and, when applicable, financial restitution to the victim. Of the two, only the former is guaranteed.{19} Impact statements were formally enshrined in law in California in 1982, when the passage of Proposition 8, the Victims’ Bill of Rights—which granted victims the right to be notified of, to attend, and to state their views at sentencing and parole hearings—allowed the presentation of victim impact statements during the sentencing of violent attackers.{20} The result was a “wholesale shift in the philosophy of the criminal justice system in California,” one that significantly restricted the rights of those accused of crimes, including harsher sentences for repeat offenses and limits on plea bargaining, in the name of expanding the rights of victims.{21}

NEW YORK TIMES, August 9, 1969.

NEW YORK TIMES, August 9, 1969.

In the 1980s and 1990s, laws enacting victim impact statements spread widely and aligned with a broader expansion of criminalization and incarceration rates across the United States. Between 1982 and 2000, dozens of states passed laws allowing victim impact statements to be used during sentencing or parole hearings. During this same period, more people were arrested, convicted, and sentenced to longer and longer sentences in the United States than ever before, producing what we now know as the era of “mass incarceration.”

The justification for victim impact statements may indeed have been restorative—to give adequate weight and standing to subjects (especially women) deemed outside the full protections of the law.{22} But their effect, largely, has been to bolster and facilitate ever more excessive prison sentences for the perpetrators of violent crimes. There are numerous reasons for this. One is that such laws, intentionally or not, have proven to suppress the voices of victims who forgive or seek leniency toward their assailants in favor of those who seek more punitive consequences.{23} Gottschalk has compared the US and European victims’ movements, finding that the American movement is not only more punitive, but has had comparatively greater influence in contributing to the nation’s incarceration bloat.{24} Impact statements now constitute a crucial pillar of many American court proceedings.

In 2018 during the sentencing of former Olympics gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar for sexual assault, the presiding judge allowed 156 women to make victim impact statements.{25} The performance of these statements arguably turned the courtroom into a dramatic stage, one that not only privileged personal testimonials to the lived and felt experience of Nassar’s victims over the more narrow legalities or illegalities of the defendant’s conduct, but which also showcased the central place given to the desire for catharsis at a pivotal site of carceral state-building. Nassar was convicted of assaulting seven women, and he had already been sentenced to sixty years in prison (on child pornography charges). Yet close to 160 women gave victim impact statements describing crimes or harms done to them for which Nassar had never been charged, and never would be. In other words, there was no legal or material purpose served by those statements; their value was symbolic, and had mostly to do with giving survivors something they felt they needed.

The recognition that one is not alone, and grasping through that recognition that the causes of suffering are systemic and not individual, is among feminism’s most powerful interventions. Around the time that the victims’ rights movement was building steam, many feminist groups were organizing listening circles that became sites for exploring and articulating the ways in which “the personal is political,” and for creating a politicized understanding of the lesser-known second half of that oft-quoted slogan: “There are no individual solutions.”{26}

ABC NEWS, January 23, 2018.

ABC NEWS, January 23, 2018.

How the courtroom came to replace the listening circle as the de facto forum for feminist recognition and restitution is integral to the story of how feminism traded the movement for the mainstream—and for the crime panics and carceral solutions promised by so much contemporary television and film, in particular the true-crime genre.

Ouellette’s research suggests that true crime began being marketed to women in the 1970s alongside the rise of the victims’ rights movement. Today, as true crime overwhelms the media landscape of nonfiction (or “unscripted”) audio, television, and film, the case is increasingly made that the genre serves a feminist function in our culture. Indeed, the market share claimed by this genre today is staggering. As of 2019, the self-described “feminist” true-crime podcast My Favorite Murder ranked number 2 on Forbes magazine’s inaugural list of highest-earning podcasts with 35 million monthly listener downloads, second only to the libertarian provocateur Joe Rogan.{27} According to Ouellette, “Women are now the presumed audience of true crime content and media across platforms.”{28}

The liberal feminist argument for true crime hangs on the promise of catharsis as a form of justice and, concurrently, on the suturing of cathartic feeling to the outcomes of criminal legal proceedings. Yet this argument operates not only to justify an insidious media form but also to validate a crime panic over “stranger danger,” especially among middle-class women, that tends to buttress carceral demands like more policing and longer sentences.{29} In the pilot episode of My Favorite Murder, hosts Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark—both middle-aged white women—talk about their fears of being attacked and killed in their own homes, and the cathartic relief they find in the incarceration of sexual predators and child molesters.{30} The fears these women express may indeed be real, but the reality of their being attacked by men they don’t already share a home with is demographically unlikely. For them, true crime functions as what Linda Williams, following Carol Clover, might call a “body genre,” which permits for its audience the mimetic expulsion of feelings of injustice.{31} The transference that body genres enable is also how a victim’s right to catharsis gets collapsed into that of the audience.

In 2019, podcast hosts Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark published a “dual memoir” titled STAY SEXY & DON’T GET MURDERED: THE DEFINITIVE HOW-TO GUIDE.

In 2019, podcast hosts Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark published a “dual memoir” titled STAY SEXY & DON’T GET MURDERED: THE DEFINITIVE HOW-TO GUIDE.

The slippage between the symbolic and the material is also why some feminists argue that testimonials of suffering—whether in courts or on screens—matter for survivors of sexual violence. The case for such staging of testimony often stems from a desire for justice that’s been rendered synonymous with a perceived right to catharsis. If one sympathizes with that desire for justice, as we should, then it becomes challenging to dispute the legitimacy of the latter. When my students, many of them female and/or trans, expressed their anger after watching The Recall, they did so having experienced their own vulnerabilities to sexual violence, especially on campus. In part because of their social proximity to college campus culture, they identified viscerally with the survivor in the Brock Turner case, and held a fair and accurate perspective on the failures of every institution in their lives, including the state, to take seriously a continued epidemic of sexual violence and to demonstrate a commitment to redressing it. It would seem that while the students could agree in theory with the abolitionist feminist analysis being offered by The Recall, they also felt unfairly dismissed by its straightforward repudiation of the instinctual left position, and the position taken by progressive feminist and student groups in real life, insofar as it had denied them a feminist right to catharsis.

But catharsis only stands in as justice when the horizon of justice is itself delineated in therapeutic terms. Victim impact statements, even at their best, are predicated on the idea of trials as arenas of recovery and healing. “Not everyone finds relief in a courtroom,” writes journalist Jill Lepore, “but many people who have endured a violent crime or lost someone they loved report feeling tremendous catharsis after having the chance to describe their suffering in court.”{32} Within the dominant common sense of neoliberal capitalism, the concept of catharsis is legible in a way that structural transformation is not. The state is unknown and amorphous, “systems” are confusing and lacking in agency, long-term transformation is frustrating to the consumerist sensibility. This may explain the narrative function of cathartic feeling in our cinema, just as in our courts—it is the result of, and salve for, a system set up materially to fail those it claims to protect. But to understand what is being gained or sacrificed when catharsis substitutes for other forms of justice, it is worth revisiting the history of the term.

****

The Roots of Catharsis

Catharsis as a term has roots in both religious puritanism and medical practices, particularly psychoanalysis. The words catharsis and cathartic both trace to the Greek kathairein, meaning “to cleanse” or “to purge.” Within the English language catharsis begins as a medical term, having to do with purging the body of unwanted or unhealthy material, a “bodily purging” most directly pertaining to physical substances, but one whose meaning also evolved to include toxins of the emotional and/or spiritual kind. Cathar as a noun dates back to at least the 1570s to mean a “religious puritan,” and was adopted by a variety of Christian puritan sects.

The first recorded incidence of catharsis used in the therapeutic sense can be traced to 1893, when Sigmund Freud and Viennese physician Josef Breuer published a paper titled “On the Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena.” Their theory was that in the “normal” course of things, the unconscious affects associated with traumatic experiences (by which they mean any experience that calls up distressing affects such as fear, anxiety, shame, or physical pain) are gradually “discharged” or worn away through various conscious or reflexive activities. However, in the case of certain patients these affects remain “strangulated,” cut off from consciousness, and subsequently manifest as “hysterical” symptoms. In such instances, the affect can be discharged or “abreacted” through a “cathartic” procedure—either by reenacting the event under hypnosis, or through the act of speaking, which serves as a substitute for the action—that is therapeutically effective in getting rid of the symptom.{33}

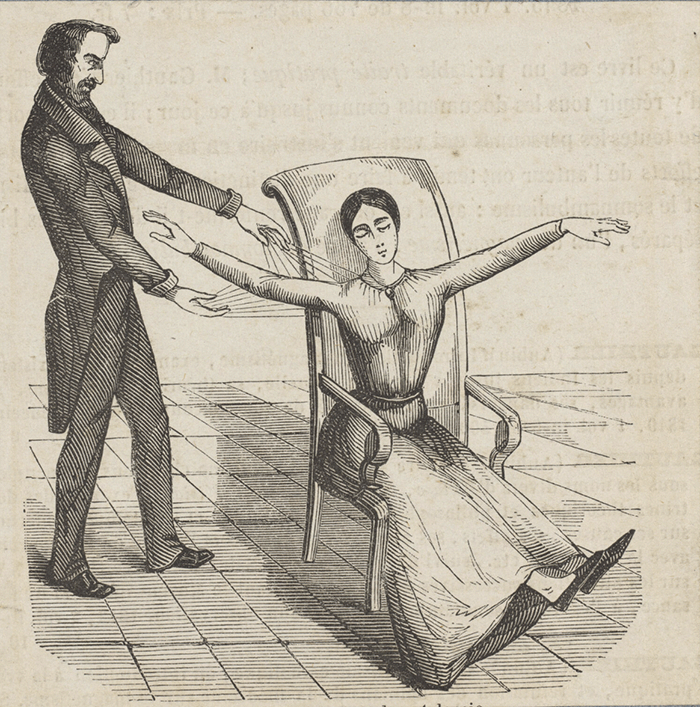

A mesmerist using animal magnetism on a female patient, ca. 1845.

A mesmerist using animal magnetism on a female patient, ca. 1845.

Although they were writing in a social context in which feminism was as yet unheard of, Breuer and Freud nevertheless played an instrumental role in the destigmatization of hysteria, which was regarded as a predominantly “feminine” disease well into the nineteenth century. Feminist historians credit one of Breuer’s patients, Bertha Pappenheim (better known as the case study “Anna O.”), for a significant shift that would become foundational to psychoanalysis and for which Freud is generally credited: the “cathartic method.” Considered radical at the time, the cathartic method—or what Pappenheim herself called the “talking cure”—was a therapeutic process that centered listening to the patient’s personal and social history rather than merely observing the patient.{34}

One of the resounding outcomes of the victims’ rights movement has been the remaking of the courtroom into a therapeutic site of catharsis, in a colloquial sense if not a clinical one. Indeed, the feminist justification of victim impact statements is predicated on the equation of catharsis with justice: Victims of harm and their loved ones could substitute for, or supplement, the biases and inadequacies of the criminal legal system by turning it into a discursive forum for acknowledging systemic sexual violence.

In this sense, the delivery of victim impact statements within criminal justice proceedings appears to function like a kind of public “talking cure,” vocalized suffering operating as a remedy for a symptom whose causes are, by and large, left unaddressed. We now use “giving a voice” as shorthand to describe and validate such vocal performances or speech acts. The judge in the Nassar trial, Rosemarie Aquilina, used this language herself on the day she sentenced Nassar to up to 175 years in prison. “I know the world is watching,” she remarked. “I give everybody a voice . . . I give defendants a voice, their families when they’re here, I give victims a voice.”{35} Her remarks are expressive of an existing discourse that frames catharsis as a feminist corrective, even a right. After all, it would seem to be making room for, and thus validating, felt experience within an arena that has historically adjudicated what counts as evidence along gendered lines.

The catharsis that victim impact statements promise isn’t unique to the courtroom. It also permeates media cultures, which we might understand as being full of extrajudicial victim impact statements. Lauren Berlant has usefully articulated concerns about “the place of painful feeling in the making of political worlds,” juxtaposing “the cultural politics of pain” with “the violence of sentimentality” to ask, “Who gave anyone expertise over the meaning of feelings of injustice?”{36} The question is rhetorical for a reason, for the only viable answer is everyone and no one. To deny anyone at least subjective “expertise” over the meaning of feelings of injustice is antithetical to a core tenet of feminist theory: the need to upset the privileging of objective over subjective knowledge that has historically been used to discredit women and others marginalized by their social position. The problem, rather, is that one way that “painful feeling” has helped in the making of political worlds is through its capture by and identification with carceral outcomes (more police, more arrests, more incarceration) and carceral outcomes alone. Thus, such outcomes and the cathartic feelings we have been socialized to experience have come to stand in for justice, without actually serving the cause of women’s safety and security.

This is precisely why abolitionist feminists have challenged the long legacy of carceral feminism, including its substitution of cathartic feeling for political demands. As Amia Srinivasan writes, “For most abolitionist thinkers . . . the proposal is not, needless to say, that the angry energies of those who are made to exist on society’s margins should be simply let loose,” but rather to consider what it would take to harness such energies and respond to real crises with solutions that actually effect security and well-being.{37} When catharsis substitutes for politics as a value and demand of our cinema, it works in much the same way feminist grievance does when attached narrowly to sentencing outcomes and state validation in our courtrooms: It buttresses the criminal justice system while undermining the cause of imagining and enacting justice in any other form.

So where are we left? By which, of course, I am asking two questions at once: How do we reconcile these wants and their contradictions, and what is the politically progressive and abolitionist position on the question of catharsis as a just demand? The answer may depend on asking a different question: What do we want?

****

The Affordances of Denial

I want to turn, in closing, to another trial film, this one a fictional narrative, whose structure and dramaturgy point to a refutation of the type of moral or emotional resolution we have been trained by juridical spectatorship to expect—and demand—in our courts and on our screens.

The 2022 film Saint Omer, by the French Senegalese filmmaker Alice Diop, is about an African immigrant mother on trial in France for the murder of her daughter. The accused is a Senegalese PhD philosophy student in France named Laurence Coly, herself a fictionalized version of a real-life French Senegalese mother named Fabienne Kabou accused in 2013 of leaving her young daughter to drown on the shores of the English Channel, and charged with first-degree murder. The fictionalized film version unfolds over the course of Coly’s public trial in France, as fitfully observed by a writer and journalist named Rama who is herself pregnant with her first child and also writing a book about Medea, the goddess of Greek myth who killed her own children in a fit of vengeful rage.

Before Saint Omer, Diop was best known for her work in documentary, her films acclaimed for their close observation of immigrant experiences within the institutional fabric of French society. This interest would seem to have brought her to the story of Fabienne Kabou. In real life, Diop attended the entire public trial of Kabou, and in Saint Omer we are invited to similarly view the trial of Laurence Coly from the perspective of a writer self-tasked with mining it for narrative meaning.{38} Much of the film is spent with the camera framed on Coly on the witness stand, her performance deliberately, and provocatively, inscrutable. We watch Coly, and we also watch Rama in the audience. We watch Rama watching Coly, and in so doing, knowing that Diop had sat in a similar courtroom watching Kabou, we watch Diop. We ourselves are watchers, and—in the parlance of the courtroom genre—we might also imagine ourselves as jurors, weighing the evidence and forensically scrutinizing the speech and behavior of the accused for clues. However, conclusive judgment, let alone moral condemnation and the resolution afforded by both consequence and explanation, is precisely what the film denies us.

We watch Coly, and we also watch Rama in the audience. We watch Rama watching Coly, and in so doing, knowing that Diop had sat in a similar courtroom watching Kabou, we watch Diop.

We ourselves are watchers, and—in the parlance of the courtroom genre—we might also imagine ourselves as jurors, weighing the evidence and forensically scrutinizing the speech and behavior of the accused for clues. However, conclusive judgment, let alone moral condemnation and the resolution afforded by both consequence and explanation, is precisely what the film denies us.

Saint Omer is bookended with two crucial challenges to the promise and designation of the trial as both theater and narrative structuring device. The first comes early, when the French judge presiding over the case addresses Coly directly (in contrast to the referee role played by the judge in the Anglo-American adversarial system, the judge in the French system plays the role of inquisitor, herself probing for information to establish truth and justice). The judge reads out the facts leading to Coly’s arrest, which suggest irrefutability in their forensic detail. “This was when you confessed,” she says to Coly, with both sympathy and confusion. “You told the detectives that you killed your daughter because, I quote, ‘I thought this would make life easier.’ You claimed to have left your daughter on the beach, believing the sea would take away her body. Ms. Coly . . . do you know why you killed your daughter?”

At this point Coly responds, “I don’t know. I hope this trial will give me the answer.” The judge, still confused, asks, “Do you accept the alleged facts?” and Coly replies, “Yes, I do . . . I plead not guilty, your honor.” In this exchange a crucial marriage falls apart: the one between action and guilt. This coupling can be untied within the existing criminal legal system as well, but usually only through two legal devices: the defense of self-defense and the defense of criminal insanity. In Coly’s trial the specter of criminal insanity is raised, but it doesn’t stick. Coly talks about premonitions, about hallucinations, about sorcery, but she doesn’t seem mad. Diop has written the systemic traumas and epistemological blinders of colonial history so seamlessly into her story that we see a Western notion like madness for what it is, a malleable and instrumentalized construct. The category (both legal and moral) of mental illness operates instead in the film like a magnet held at the wrong pole, repelling instead of attracting an easy out.

The second challenge comes at the end, and my description of it will spoil the film for those who haven’t seen it. In a bold and considered cinematic choice, Diop ends the film before a verdict in the court case is reached. We have been successfully led through a tense and suspenseful courtroom drama, but ultimately denied the trial genre’s most critical plot point—the verdict. We do not find out Coly’s fate. Without a decision as to the “guilt” or “innocence” of the accused, the substance of the investigation itself is rehung on new terms: motherhood, colonialism, the indivisibility of the individual and their society, race and racism, and the slipperiness of language itself.

We the audience thus may experience some feeling of being “robbed”—similar perhaps to my students watching The Recall, albeit different in emotional results. We have been riveted by a murder trial that evokes age-old taboos (infanticide) and complicated modern politics (neocolonialism). We have been invited to watch this trial from the overlapping perspectives of a journalist, a documentarian, and a jury, weighing evidence and testimony, scrutinizing the faces and body language of our witnesses, wrestling with the very existential meaning of guilt and innocence. All this, only to be denied a “conclusion” to this trial to invariably weigh our own pronouncement against. What, then, might this denial afford?

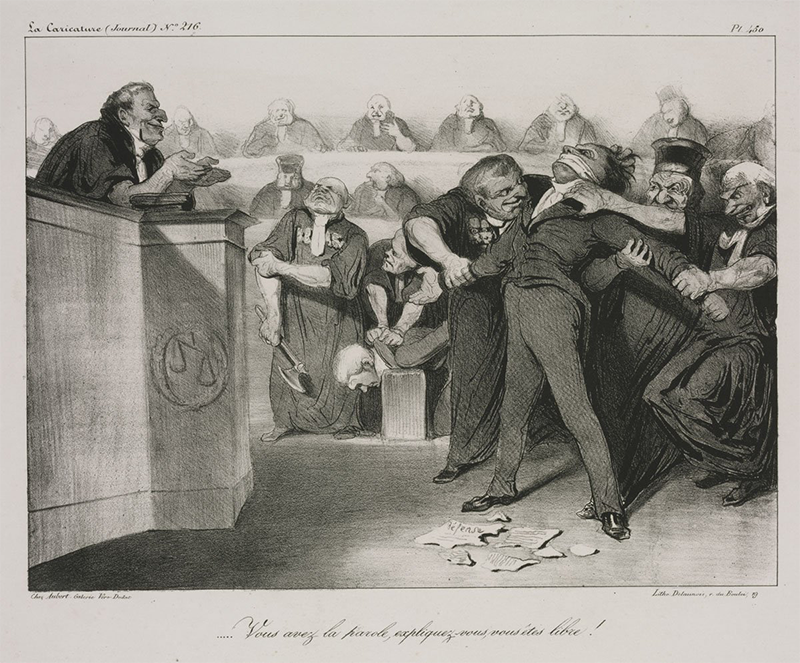

The performance of Guslagie Malanda in the role of Laurence Coly recalls a nineteenth-century political cartoon by the artist Honoré Daumier, in which an accused man is gagged and held down while the court judge says, “You have the floor . . . explain yourself.” As the critic Yasmina Price notes, this is the very essence of the modern legal apparatus: “What could a black woman, Senegalese and a mother, expect of this law and these conditions of speech?”{39} For much of her screen time, Coly is silent, her face and body language refusing to offer decipherable speech of any kind. The trap has already been set for the colonial subject, a black immigrant mother of a mixed-race child. The situation, her silence conveys, is impossible.

Honoré Daumier, “Vous avez la parole, expliquez-vous, vous êtes libre!,” LA CARICATURE, no. 216, May 14, 1835.

Honoré Daumier, “Vous avez la parole, expliquez-vous, vous êtes libre!,” LA CARICATURE, no. 216, May 14, 1835.

Refusing the protocols of both feminist scripts for punishment and verdict-oriented courtroom dramaturgy, Saint Omer offers an abolitionist rejoinder to the ideological and libidinal politics of carceral catharsis. We are neither presented with impeachable forensics as the basis for moral truths or legal verdicts, nor are we asked to be apologists for our protagonist’s claims of sorcery and hallucinations by easily mapping a diagnosis of mental illness onto her narrative. We conclude not only with the unknowability of the court’s verdict, but with a larger, more meaningful unknowability: Where does action come from? How do intergenerational trauma and historical violence live out in the present? What constitutes justice in an unjust world?

Motive, causality, will, and responsibility are all put into question, and as such we are unrooted from the demands of individuated rights and responsibilities that ground modern criminal legal systems in the West, as well as the carceral logic that pervades narrative construction in our cinema. Storytelling itself is challenged, at least in its most propertied form, for the strangeness and violence of human experience on display for various layers of audience in this film defy the very boundaries of individuated selfhood—a precondition for both victim and perpetrator within modern criminal legal systems—and its actions.

We are destabilized, and it is from this state that we simultaneously empathize and identify with Rama, with the judge, with Coly, with Coly’s mother, and perhaps even with her dead daughter, another person shortchanged by something greater than one individual and their faults.

Catharsis, resolution, satisfaction, purging—these are not emotions in and of themselves, but prescribed remedies to psychic or affective needs that themselves have become tethered to particular institutional horizons and narrative fantasies. I use the word prescribe deliberately. It is a term both medical and literary; it means to authorize a remedy by writing it into being. We are injured by the world, and so it leaves us wanting. Catharsis would thus seem to be a fair ask, maybe even a right. But once prescribed by our culture, whether in courtrooms or in classrooms or on screens, it leaves little place for other, better salves.

Perhaps our want is not the problem in itself. Perhaps it is instead the want’s want.

I showed Saint Omer to my students, and notably none of them expressed the same feelings of frustration, as though they’d been denied something, as they did in the case of The Recall. They accepted the instability and danger of Saint Omer’s narrative and they also accepted—and enjoyed—that the film somehow succeeds as a narrative while leaving us with want. We may not know what to answer that want with, but the want itself operates as a promise and a potential, rather than a wound.

It makes me wonder. Could I acknowledge to my students that they were not wrong to want Brock Turner to serve a longer sentence or be subjected to punishment seemingly commensurate with the harm caused to his victim, Chanel, and commensurate with the experience of hundreds of thousands of black and brown, poor and precarious prisoners victimized by the carceral state through long and punishing prison sentences? Those injuries and insecurities are real, and so long as they go unresolved they should leave us wanting. You are wrong neither for wanting this, nor for the feeling that a different verdict, one that left you feeling less emotionally hollow than the one Judge Persky delivered, would somehow better line up with your desire for racial and gender justice. But could you imagine wanting something else? Could another outcome for both Brock Turner and Chanel Miller produce the same feeling of catharsis—perhaps an outcome that more closely aligns with your desire to see the end of sexual violence, the actuality of bodily safety, the reduction or even abolition of racialized vulnerability to state-sanctioned unfreedom and death? The space—or perhaps the scene—to ask my students this question, that is one want.

Acknowledgment: This essay is part of a larger manuscript collaboration with the scholar Pooja Rangan on the making and unmaking of a carceral common sense in documentary cinema. As such, some of the sections were coauthored, and all of them strengthened by her incisive feedback and ideas.

Title video: The Recall: Reframed (Rebecca Richman Cohen, 2018).

{1} Lauren Berlant, “The Subject of True Feeling,” in Left Legalism/Left Critique, ed. Wendy Brown and Janet Halley (Duke University Press, 2002), 105–33.

{2} Renee Heberle, “The Personal Is Political,” in The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory, ed. Mary Hawkesworth and Lisa Disch (Oxford University Press, 2015), 593–609.

{3} Richard Gonzales and Camila Domonoske, “Voters Recall Aaron Persky, Judge Who Sentenced Brock Turner,” NPR, June 5, 2018.

{4} Jeannie Suk Gersen, “Revisiting the Brock Turner Case,” New Yorker, March 29, 2023.

{5} Sam Levin, “Stanford Trial Judge Overseeing Much Harsher Sentence for Similar Assault Case,” Guardian, June 27, 2016.

{6} Katie J. M. Baker, “Here’s the Powerful Letter the Stanford Victim Read to Her Attacker,” BuzzFeed News, June 3, 2016.

{7} Mariame Kaba, “Transforming Punishment: What Is Accountability Without Punishment? (with Rachel Herzing),” in We Do This ’til We Free Us, ed. Tamara Nopper (Haymarket Books, 2021), 133.

{8} Aya Gruber, The Feminist War on Crime: The Unexpected Role of Women’s Liberation in Mass Incarceration (University of California Press, 2020), 6.

{9} Elizabeth Bernstein, “The Sexual Politics of the ‘New Abolitionism,’” Differences 18, no. 3 (2007): 137; Angela Y. Davis, Gina Dent, Erica R. Meiners, and Beth E. Richie, Abolition. Feminism. Now. (Haymarket Books, 2022), 107.

{10} Gruber, Feminist War on Crime, 9.

{11} Jill Lepore, “The Rise of the Victims’-Rights Movement,” New Yorker, May 14, 2018.

{12} Melissa Morabito, April Pattavina, and Linda Williams, “It All Just Piles Up: Challenges to Victim Credibility Accumulate to Influence Sexual Assault Case Processing,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34, no. 15 (2016): 3152–53; Andrew Dam, “Less than 1% of Rapes Lead to Felony Convictions. At Least 89% of Victims Face Emotional and Physical Consequences,” Washington Post, October 6, 2018.

{13} Morabito et al., “All Just Piles Up,” 3156–57.

{14} Laurie Ouellette, “Carceral Feminism on Repeat: The Enduring Appeal of Law & Order: SVU,” Film Quarterly 76, no. 4 (2023): 73–74.

{15} Carrie Rentschler, Second Wounds: Victims’ Rights and the Media in the U.S. (Duke University Press, 2011), 6.

{16} Marie Gottschalk, The Prison and the Gallows: The Politics of Mass Incarceration in America (Cambridge University Press, 2006), 6.

{17} Gruber, Feminist War on Crime, 98.

{18} The Lily News, “How Sharon Tate Became the Face of Victims’ Rights,” Washington Post, November 21, 2017.

{19} “Victim Impact Statements,” Criminal Division, US Department of Justice, accessed April 2, 2025.

{20} Miguel Méndez, “The Victims’ Bill of Rights—Thirty Years under Proposition 8,” Stanford Law & Policy Review 25 (2014): 379–434.

{21} J. Clark Kelso and Brigitte A. Bass, “The Victims’ Bill Of Rights: Where Did It Come From and How Much Did It Do?,” University of the Pacific Law Review 23, no. 1 (1991): 878; Méndez, “Victims’ Bill of Rights,” 433–34.

{22} Gruber, Feminist War on Crime, 99.

{23} Mary Margaret Giannini, for example, writes of the “often-inaccurate dichotomy of the innocent and vengeful victim seeking a harsh punishment for the reprehensible defendant” and the relevance of “circumstances at sentencing where victims express statements of mercy [or] forgiveness.” Mary Margaret Giannini, “Equal Rights for Equal Rites?: Victim Allocution, Defendant Allocution, and the Crime Victims’ Rights Act,” Yale Law & Policy Review 26, no. 2 (Spring 2008): 431, 473, quoted in Hugh M. Mundy, “Forgiven, Forgotten? Rethinking Victim’s Impact Statements for an Era of Decarceration,” UCLA Law Review, October 30, 2020.

{24} Gottschalk, Prison and the Gallows, 97–114.

{25} Tom Lutz, “Victim Impact Statements against Larry Nassar: ‘I Thought I Was Going to Die,’” Guardian, January 24, 2018.

{26} Paige Sarlin, “Radical Assertions: Collective Interview Work in The Woman’s Film (1971),” unpublished manuscript, February 6, 2025.

{27} Ariel Shapiro, “Crime Does Pay: ‘My Favorite Murder’ Stars Join Joe Rogan as Nation’s Highest-Earning Podcasters,” Forbes, February 3, 2020.

{28} Laurie Ouellette, “Stay Sexy and Don’t Get Murdered: White Feminism and True Crime For Women,” in Race/Gender/Class/Media: Considering Diversity Across Audiences, Content, and Producers, ed. Rebecca Ann Lind (Routledge, 2023), 237.

{29} Pooja Rangan and Brett Story, “Four Propositions on True Crime and Abolition,” World Records Journal 5 (2021).

{30} Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark, hosts, My Favorite Murder, podcast, season 1, episode 1, “My Firstest Murder,” Exactly Right, January 13, 2016.

{31} Carol J. Clover, “Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film,” Representations 20 (1987): 189, quoted in Linda Williams, “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess,” Film Quarterly 44, no. 4 (1991): 4. Whereas Clover’s analysis focuses primarily on horror films, Williams focuses on “the woman’s film” or “weepie” as the form that has most preoccupied feminist film theorists, arguing that its success lies in the extent to which the audience mimics the sensations depicted onscreen—in the case of the melodrama, dissolving in tears (5).

{32} Lepore, “Victims’-Rights Movement.”

{33} Sigmund Freud, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume II (1893–1895): Studies on Hysteria by Josef Breuer and Sigmund Freud, trans. James Strachey (Hogarth, 1981), xiii–xix, 6, 8. The entire remarkable passage describing this theory is worthy quoting for its account of catharsis as a therapeutic counterweight to injury or trauma:

Hysterics suffer mainly from reminiscences.

At first sight it seems extraordinary that events experienced so long ago should continue to operate so intensely—that their recollection should not be liable to the wearing away process to which, after all, we see all our memories succumb. The following considerations may perhaps make this a little more intelligible.

The fading of a memory or the losing of its affect depends on various factors. The most important of these is whether there has been an energetic reaction to the event that provokes an affect. By “reaction” we here understand the whole class of voluntary and involuntary reflexes—from tears to acts of revenge—in which, as experience shows us, the affects are discharged. If this reaction takes place to a sufficient amount a large part of the affect disappears as a result. Linguistic usage bears witness to this fact of daily observation by such phrases as “to cry oneself out” [“sich ausweinen”], and to “blow off steam” [“sich austoben,” literally “to rage oneself out”]. If the reaction is suppressed, the affect remains attached to the memory. An injury that has been repaid, even if only in words, is recollected quite differently from one that has had to be accepted.

Language recognizes this distinction, too, in its mental and physical consequences; it very characteristically describes an injury that has been suffered in silence as “a mortification” [“Kränkung,” lit. “making ill”]. The injured person’s reaction to the trauma only exercises a completely “cathartic” effect if it is an adequate reaction—as, for instance, revenge. But language serves as a substitute for action; by its help, an affect can be “abreacted” almost as effectively. In other cases speaking is itself the adequate reflex, when, for instance, it is a lamentation or giving utterance to a tormenting secret, e.g. a confession. If there is no such reaction, whether in deeds or words, or in the mildest cases in tears, any recollection of the event retains its affective tone to begin with. (8)

{34} Dianne Hunter, “Hysteria, Psychoanalysis, and Feminism: The Case of Anna O.,” Feminist Studies 9, no. 3 (1983): 469.

{35} Lepore, “Victims’-Rights Movement.”

{36} Lauren Berlant, The Queen of America Goes to Washington City: Essays on Sex and Citizenship (Duke University Press, 1997), 123. Berlant’s work helps explain how such ideas circulate in the visual world of American dominant culture. Berlant describes, for example, the circulation of “new sentimental icons of national culture,” writing that within such iconography “pain proves victimization; victimization signals unjust power; the world of light will be achieved only when the body is safe for the future” (123). They are discussing specifically the visual narratives that reify pro-life discourse, but as we know, the pro-life movement has done much to subsume the language and figure of the victim into its own invectives against those seeking to terminate a pregnancy.

{37} Amia Srinivasan, The Right to Sex: Feminism in the Twenty-First Century (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), 171.

{38} Lindsey Bahr, “Q&A: Filmmaker Alice Diop Mines Darkness in ‘Saint Omer,’” AP News, January 12, 2023.

{39} Yasmina Price, “Mothers and Mothering,” Africa Is a Country, January 11, 2023.