The verdict is in: true crime has been reformed.

Journalists and scholars alike have announced the genre’s elevation from tabloid fodder to public enlightenment. Prestige programs that reconsider past cases (Serial, 2014), call for wrongful convictions to be overturned (Making a Murderer, 2015), or are instrumental in bringing cases to trial (The Jinx, 2015) have been called “the new true crime”: a socially-minded and formally reflexive nonfiction genre that exposes established legal truths as scapegoating fictions.{1} If it exploits or sensationalizes human misery, the new true crime does so in service of justice, achieving, one critic claims, a sort of “trash balance . . . with only one bad ending instead of two.”{2}

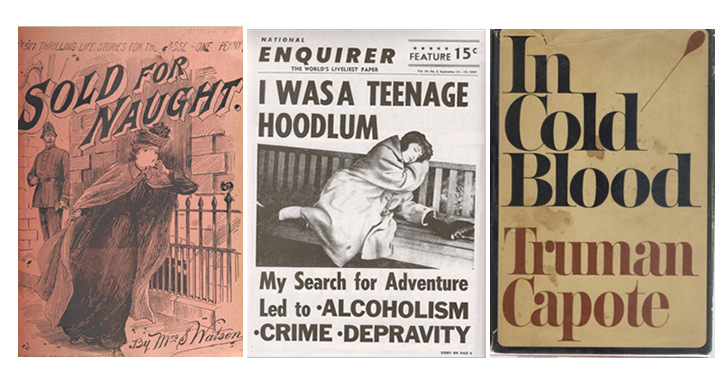

To launder its tawdry reputation, this new, justice-driven true crime borrows directly from the stylings of documentary, understood conventionally as a vehicle for social justice and humanitarian advocacy. The true crime of previous eras—the Victorian-era “penny dreadful,” the tabloid, the dystopian crime novel—spoke to audiences in the titillating language of perverse criminality and intrepid police work. Today’s true crime titillates with the promise of justice. “We are trying everything possible to not feel exploitative or, you know, the Nancy Grace type of a titillating thing or ‘Let’s get ratings off of the death of somebody,’” says Serial’s executive producer Julie Snyder.{3} The criminal justice system did not “work” for the Central Park Five, just as it “failed” Adnan Syed. The proof is in the pudding, says The Jinx: while poor men and women of color are locked up despite a dearth of evidence, scions of the white, wealthy billionaire class walk free.

Figure 1. The true crime of previous eras—the Victorian-era “penny dreadful,” the tabloid, and the crime novel.

Figure 1. The true crime of previous eras—the Victorian-era “penny dreadful,” the tabloid, and the crime novel.

True crime and the social justice documentary have long shared a penchant for narratives plotted through mysteries, miseries, and misdemeanors. But critique of the criminal justice system is relatively new terrain for true crime. Some may hail this as progress, a sign that the entertainment industry is awake, finally, to the racist and classist codes through which true crime narratives have historically spoken. But the more skeptical view suggests a great cultural rebranding, a twenty-first-century revitalization of a genre form and its profit margins. In what is ultimately a reformist project that upholds the system as a whole, documentary serves as the tutor, innocence stories as the vocabulary, and bipartisan criminal justice reform at the level of elite governance as the model—and the bloody glove.

True crime is not the ally of justice, but its antinomy. What follows are four propositions on the reformist collaboration between true crime and documentary, the seductive fiction of crime, and the false promises of a justice staked on innocence and redemption. What we call for instead is a form of abolition documentary that relinquishes, once and for all, its investments in the category of crime altogether.

****

1. Crime is a Lie Based in Reality

True crime documentary may challenge the institutional performance of justice, but like the criminal justice reform movement, its makers, audiences, and critics seem unable to shake their addiction to the very thing standing in the way of actual transformation: crime.

Crime, the genre says to us, is worth documenting because it is the thing that’s true. But crime and criminality are invented and mutable constructs. This bears repeating, for as obvious as it might appear, it is easy to lose sight of crime’s basic artifactuality when documentarians (even those invested in challenging the truth claims attached to “evidence vérité,” that is, the filmed footage of arrests, confessions, and crime scenes admitted in courts of law as the best evidence of what occured) are forensically preoccupied with who committed it, when, and in what order.{4}

Crime as a category is determined by social actors making decisions in a particular time and place. This makes crime an artifact of competing struggles and social antagonisms. Unlike other social constructs whose meaning is relative and mobile, however, crime is invested with both legal and moral authority. It’s easy to forget this when we use crime as a synonym for harm: not all crimes are harms and not all harms are crimes.

There are two problems with the category of crime. The first is the unique moral consensus it is able to generate regarding what kinds of action, being, or behavior are so “wrong” that they deserve legal sanction by the state; the second has to do with how, by invoking crime specifically (as opposed to any other index of harm), we empower and legitimate the most coercive institutions of the state, and trigger a cascade of punitive and oppressive activities.

Crime is almost always equated with wrong. And yet, what equals crime, and thus criminality, routinely delimits threat and violation in terms that ratify existing or desired structures of power. In newly industrializing England, for instance, what constituted a criminal offense was determined by the vicissitudes of an emerging private property regime that dispossessed many of their access to basic resources for survival. New categories of urban “crime,” often designating offenses against property, took aim at peasants who, deprived of access to fields to grow crops and raise animals, and to forests for the foraging of wood for fire and shelter, were driven into emerging cities and forced to sell their labor under threat of starvation.{5} Across the ocean, in the radical period of Black empowerment and experimentation following the US Civil War that is commonly known as Reconstruction, anxiety over the changing racial and social order was channelled into an emerging moral panic that systematically coded crime for the first time as both urban and Black.{6}

This recipe (of mapping generalized anxieties about the social order onto moral panics about “crime,” and then conflating crime with Blackness, poverty, and urban strife) has proven endlessly recyclable.{7} We saw it in President Trump’s invocation of “rioters and looters” in his authorization of a militarized police response to nationwide protests against systemic racism and police brutality.{8} But the criminalization of dissent has never been partisan, and the category of the criminal has offered a useful alibi for Republicans and Democrats alike. Four days after the eruption of the Detroit rebellion of 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson specifically invoked the vocabulary of criminality to undermine Black and brown civil rights protesters shut out of the formal labor market as looters, and as criminals.{9} This was months before President Richard Nixon, Johnson’s successor, would declare his own “war on crime,” redirecting anxiety about his wars in Southeast Asia with ominous warnings about “narcotics addicts” turning to “shoplifting, mugging, burglary, armed robbery, and so on,” unless the state took action.{10} And while the 2.2 million people currently captive in American prisons are not all political dissidents, mass incarceration must still be understood as a political project, insofar as the vast majority of the criminalized are poor, working-class, Black and brown members of the most systematically disenfranchised strata of the contemporary social order.

Crime as a socio-legal construct does not only provide a convenient cover for the social crises endemic to racial capitalism. It also authorizes a set of violent and punitive intrusions by the state into the lives of its citizens, and, increasingly, non-citizens. The manipulation and expansion of the carceral system in the name of crime reached its apogee in the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, otherwise known as the 1994 Crime Bill. Authored by member of Congress Joe Biden and signed into law by President Bill Clinton, the act underwrote funding for 100,000 new police officers and designated more than sixty new legal categories of capital crimes. It also earmarked money for new prison construction, 4,000 new border control officers, and the expansion of capital punishment.

The specter of crime works by ideologically marrying its appearance as a natural, primordial phenomenon (crime as deviance and deviance as inevitability) with its emotional resonance (fear, and the desire to be free of it). A 2014 study by the Annenberg Public Policy Center shows that among US audiences, rising fears of crime have paralleled the rise of violent crime TV programming since the 1990s, even though actual violent crime rates have fallen dramatically in this same period.{11} Fear of crime, in other words, is produced and orchestrated, but is often at odds with the existence of actual threat. The serialization of true crime as an unceasing backdrop of and soundtrack for our lives harmonizes cultural heartbeats with the thrum of a carceral system for whose exponential growth crime has served as a false alibi.

What this suggests is that documentarians invested in justice who make films that pivot on forensic dramas of innocence are not only flirting with accusations of exploitation. They are staging the wrong conversation altogether, one that accomplishes little in terms of dismantling the actual structures of harm and the processes that manufacture crime as a rationale for social and material dispossession.

****

2. Innocence is a Problem

“The innocence industry,” James Kilgore observes, “is both opening minds and gaining market share.”{12} And indeed, innocence stories are not only generating hitherto unheard of revenues; an inordinate amount of time and money is also being invested into overturning wrongful convictions by lawyers, social justice activists, and the families of incarcerated people.{13}

Wrongful convictions are the clearest abrogations of the promise of criminal justice, on both moral and legal grounds. It is only through the category of guilt that the state is authorized to inflict the most punishing of actions on its citizens: the deprivation of liberty, and even life itself. What is deemed fair and just for the guilty is shocking in its cruelty and violation when inflicted upon the innocent. This is why there is such reliance on innocence stories to do work on behalf of reform advocacy.

Seen from another vantage, however, documentary media, true crime, and criminal justice reform collaborate on what we call an innocence problem. Innocence here refers to both a judicial verdict (as in, the opposite of guilt as concluded by a court of law), and a modifier within crime’s spectrum of perceived harms (the person who steals some baby formula and is locked up under a “third strike law” relative to the person convicted of assault and battery). The problem with innocence is the support it lends to a punitive carceral state, as categories of innocence, even relative innocence, reify guilt as justification for often severe punitive action. Innocence and guilt coauthor the legal and moral construct that enables the system as a whole: crime.

Several criminal justice campaigns of the last few years have been so focused on redeeming particular kinds of offenses and the people found guilty of them (for instance, marijuana possession) that they have reinforced the hardening of the system for all others. Ruth Wilson Gilmore, for example, notes the consequences of appeals to “relative innocence” when she writes: “most campaigns to decrease sentences for nonviolent convictions simultaneously decrease pressure to revise—indeed often explicitly promise never to change—sentences for serious, violent or sexual felonies.”{14} As the freedom of so called non-violent and drug offenders is increasingly purchased through appeals to relative innocence, those labeled by the state as violent or as sex offenders pay the price in terms of longer, harsher sentences and further disposability in public opinion.

A similar reinforcement of the system as a whole through the privileging of innocence stories occurs in true crime documentaries, including those that advocate for the decarceration of nonviolent offenders trapped in a reincarceration cycle for parole or probation violations. The recent Amazon series Free Meek (2019) is an instructive example. Narrated and re-enacted by hip-hop artist Meek Mill and his many advocates, who provide its textual voice and moral center, the series traces the ongoing aftermath of Mill’s wrongful arrest at age nineteen, which has led to Mill being incarcerated, under house arrest, or on probation for his entire adult life.

Mill freely admits to carrying a gun when he was arrested, and to various technical violations of his probation. What makes Free Meek compelling and symptomatic is its assertion of Mill’s innocence despite his guilt: innocence, that is, relative to a harsh and unreasonable punishment that does not fit the crime. The series gives equal airtime to a now-familiar repertoire of tropes that reclaim the innocence denied Mill racially as well as factually (childhood photographs, church scenes, home movies), and to a forensic investigation of his criminally corrupt arresting officers and a pathologically punitive judge on whom it declares a guilty verdict.

In the final exhilarating scene of the series, Mill performs his radicalization as an activist using his celebrity for change for a stadium of screaming fans. Here, Mill uses the emotional power of his own story to proselytize the mission of Reform Alliance, the organization he has co-founded to lobby for probation and parole reform:

Making sure people that don’t belong in prison is not in motherfucking prison. Making sure people not being locked in chains and shackled inside of cells because they whip wheelied a dirt bike or popped a percocet or smoked some marijuana. If you got a family member in prison cause of some dumb shit make some noise, we need your support!

Mill’s performance is a remarkable document of an increasingly mainstream prison reform movement under whose aegis partnerships are being forged among documentarians, celebrities, activists, corporate interests, and politicians. Indeed, the true crime documentary offers a ready vehicle for reform efforts that purport to save a broken and bloated US prison system from itself. But when Kim Kardashian lobbies a reality TV star turned Republican President on behalf of incarcerated women, and Jay-Z and Meek Mill serve alongside former Goldman Sachs partners on a prison reform nonprofit board, we have to ask: do bipartisan reform efforts that hinge on innocence stories protect the innocent, or do they produce a class of innocents in whose name violence can be done?

****

3. Justice that Reinforces "Criminal Justice" is No Justice at All

With increasing frequency, the social justice bonafides of critically acclaimed independent documentary filmmakers are being traded as currency in high-profile true crime projects commissioned by well-resourced streamers and broadcasters seeking high returns on their investment.{15} In fact, true crime and social justice documentary have been trading tropes, and talent, for decades. As Laurie Ouellette has argued, the notoriously racist COPS (1989-2020), which became the prototype for various “true justice entertainment” collaborations among television networks and law enforcement, derives its “gritty” aesthetic from respectable verité-style documentaries from previous decades, like Frederick Wiseman’s Law and Order (1969) and Alan and Janice Raymond’s Police Tapes (1976).{16}

Of course, not all crime- and criminal justice-focused moving image works are made equal.{17} The same can be said of criminal justice reforms. This is why prison abolitionists make an important distinction between reforms that ultimately widen the net of social control and those that shrink that net. The difference can be described as one between non-reformist reforms, and reformist reforms. Or, more simply, between reform and abolition.

Figure 2. Launch of Reform Alliance, a criminal justice reform organization co-founded by Meek Mill. L-R: Jay-Z, Michael Novogratz, Robert Kraft, Michael Rubin, Van Jones, Meek Mill, Clara Wu Tsai, and Daniel

Loeb.

Figure 2. Launch of Reform Alliance, a criminal justice reform organization co-founded by Meek Mill. L-R: Jay-Z, Michael Novogratz, Robert Kraft, Michael Rubin, Van Jones, Meek Mill, Clara Wu Tsai, and Daniel

Loeb.

The framework of abolition is the most useful barometer of a reform’s long term consequences precisely because abolition, as a project and a movement, aims at social transformation. At its core, abolition is not a negative project but a visionary one: a project that works to produce safety without the safeguard of violence by building social capacities and public infrastructures that increase access and reduce harm. Not satisfied with tweaks and glosses, abolition is aimed at transforming the very social relations, conditions, and logics that produce the kinds of events and behaviors for which criminalization and incarceration seem to serve as solutions.

Abolition offers a useful metric for evaluating the long-term effects of particular policies and legal changes, but also offers a way of gauging just how “just” our crime-obsessed nonfiction media actually is. For all their promises, good intentions, and occasional “wins,” true crime and documentary have come to collaborate on a crime genre reform project not unlike the bipartisan criminal justice reform project currently being performed at the federal level that has Jared Kushner, Newt Gingrich, and the union-busting Koch Brothers (not to mention our “top cop” Kamala Harris) rebranding themselves as champions of penal reform. It is a project that leaves the bedrock legitimacy of the carceral state—that constellation of public infrastructures that includes police, prisons, criminal courts, parole, and probation—firmly intact.

Indeed, true crime’s social vision resounds with increasing frequency in social media activism calling for criminally racist police to be arrested, indicted, and brought to justice. The question that such thinking about the true face of crime and its remedy leaves unexplored is this: what work does the category of “crime” itself do for the contemporary social order, and what might it might mean to live without this category as makers and consumers of justice-driven documentary?

****

4. Abolition Documentary Means Abolishing Crime Stories

One answer is that documentary makers actually have to contend, finally and fitfully, with instability and with crisis. As Stuart Hall and Bill Schwartz observed, “crises occur when the social formation can no longer be reproduced on the basis of the preexisting system of social relations.”{18} The outcome of crisis can only be determined through struggle. But struggle is precisely what is denied to us by a documentary media, including true crime, that would prefer to deliberate over questions of guilt and innocence than on the crises for which crime and its attendant institutions serve as deputies and cover stories.

Prisons and policing are rooted in crises of various kinds: crises of inequality, of deindustrialization, of state formation, of capital accumulation, to say nothing of the reproduction of white supremacy, settler colonialism, transphobia, ableism, and their instabilities. Police and prisons do not so much resolve these crises as they “fix” them, enabling the social formation to live on another day.

When we subsume the problems of a society into the dramatic linearity of a police procedural or a courtroom trial, with its performances of evidence, witnessing, confession, and the adjudication of punishment, we contribute to distorted common sense narratives about where danger comes from and who is at risk. Reiterating crime as reality serves to disavow the ways in which a social and economic order predicated on racialized exploitation, dispossession, and profit is inherently unstable and itself inflicts injury and abuse at multiple scales. And it absolves us—the spectators of the guilty pleasures of true crime dramas—of contending with that instability through social struggle.

Crime must be abolished from the documentary vocabulary because crime is a lie. To say that crime is a lie is not to say that harm, mistreatment, violation, and violence, both interpersonal and systemic, are not part of daily lived reality. Nor is it to say that these harms should not be examined and addressed by justice-seeking people. It is instead to argue that calling something a “crime” does a particular kind of work and authors a particular kind of script onto the insecurities and anxieties of a society. Crime is the stabilization of such insecurity and anxiety by state power. As a category of moral panic and prosecutable legal offense, crime authorizes the most punitive, coercive, and indeed violent apparatuses of a state while simultaneously describing the world in a particular way: as composed of the guilty and the innocent, of choices and behaviors, of individual perpetrators and of individual victims. Crime colonizes the imagination the moment it is invoked, and makes it difficult, if not impossible, to produce media whose responses and interventions do not rely on police, prisons, courts, or the criminal justice system.

Calling crime a true lie, then, is a way of insisting on an abolitionist politics in our documentary media. This is a politics that refuses the allure of the criminal case as a stabilizing narrative, that illuminates the social conditions of a moral panic, and that disinvests from the racialized codes that masquerade as natural law. As an insurgent abolition movement gains momentum across the United States, a movement that simultaneously critiques and eclipses hollow performances of reformist justice at the elite level, documentary media must follow its lead, letting go of guilt, innocence, and the category of crime altogether in an abolition movement against itself.

We thank our readers, Paige Sarlin, Genevieve Yue, Josh Guilford, and Jason Fox for helping us arrive at this distillation of our ideas.

Background Video: President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Address to the Nation on Civil Disorders (July 17, 1967), President Nixon Declares Drug Abuse “Public Enemy Number One” (June 17, 1971), Bill Clinton Speech After Signing the 1994 Crime Bill, President Trump condemns ‘rioting, looting’ in ‘Democrat-run cities like Kenosha’ (August, 27, 2020) // Free Meek (USA, 2019) // The 13th (DuVernay, USA, 2016), Senator Kamala Harris Defends Her Criminal Justice Record at a Democratic presidential debate in Houston (September 12, 2019) // Time (Garrett Bradley, USA, 2020)

{1} Lenika Cruz, “The New True Crime,” The Atlantic, June 11, 2015, Stella Bruzzi, “Making a Genre: The Case of the Contemporary True Crime Documentary,” Law and Humanities 10, no. 2 (2016): 249-280. Bruzzi describes the contemporary true crime documentary as an expansive genre that includes podcasts, series, and one-off documentaries, and embraces an eclectic range of fictional and factual conventions (including but not limited to those of the trial/crime drama), but which is bound by common concerns with the representation of the law, the truth, evidence, and miscarriages of justice. Many view Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line (1988) as an aesthetic and moral trailblazer in using documentary means to expose criminal injustice; see for instance Linda Williams, “Mirrors Without Memories: Truth, History, and the New Documentary (1993),” in The Documentary Film Reader, ed. Jonathan Kahana (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 794-806.

{2} Soraya Roberts, “True Crime and the Trash Balance,” Longreads, January 2019.

{3} Adrienne LaFrance, “Is it Wrong to be Hooked on Serial?” The Atlantic, November 8, 2014.

{4} Jessica Silbey, “Evidence Verité and the Law of Film” (2010) quoted in Bruzzi, “Making a Genre,” 251.

{5} Peter Linebaugh, The London Hanged (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), xxiii.

{6} Khalil Gibran Muhammed, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America, Second Ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019), 3.

{7} Christian Parenti, Lockdown America: Police and Prisons in the Age of Crisis (New York: Verso, 1999), 7.

{8} Trump’s conspicuous refusal to condemn white supremacists who attacked the Capitol seeking to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election is a corollary of crime’s racialization.

{9} The National Advisory Commission of Civil Disorders, “Excerpt from President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Address to the Nation on Civil Disorders (July 17, 1967),” in Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Washington DC: National Institute of Justice, 1967), 297.

{10} Richard Nixon, “Remarks About an Intensified Program for Drug Abuse Prevention and Control,” June 17, 1971.

{11} Benjamin Fearnow, “Study: TV Violence Linked to ‘Imagined’ Fears of Real-Life US Crime,” CBS DC, June 19, 2014.

{12} James Kilgore, “Are Shows like Serial and Making a Murderer Clouding the Wider Struggle for Justice?,” Truthout, March 16, 2016. Kilgore points out how even after the end of their series, the two creators of Serial later capitalized on their popular series by launching a speaking tour where tickets cost up to $125.

{13} Often credited with launching what is today a 2,800-plus strong true crime podcast industry, the blockbuster podcast Serial (which famously reopened the case of Adnan Syed, convicted for the murder of eighteen-year-old Hae Min Lee in 1999) became the podcast to most quickly reach five million downloads and streams in the history of iTunes. Advertising revenue from podcasts in the US recently jumped 53% in a single year (from $314 million in 2017 to $479 in 2018). True crime streaming and broadcast numbers have broken Nielsen records during the COVID-19 pandemic: Netflix’s Tiger King drew a staggering 34 million unique viewers within the first ten days of its March 2020 release, and ratings for the Investigation Discovery Channel, which broadcasts exclusively true crime content, were the Discovery network’s highest in six weeks in early April. See Melissa Chan, “‘Real People Keep Getting Re- traumatized.’: The Human Cost of Binge-Watching True Crime Series,” Time, April 24, 2020.

{14} Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “The Worrying State of the Anti-Prison Movement,” Social Justice, February 13, 2015.

{15} Recent examples include HBO’s The Vow (2020), an exposé of the self-improvement group NXIVM, helmed by the Oscar-nominated and Emmy-winning directors of investigative films about the Al Jazeera news network and the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal, and the Netflix miniseries Trial By Media (2020), whose slate of directors includes Yance Ford (Strong Island, 2017) and Garrett Bradley (Time, 2020), whose feature films on mass incarceration and racial injustice have been praised for their artistry.

{16} Laurie Ouellete, “Cancelling COPS,” Film Quarterly Quorum, June 17, 2020. COPS, which was canceled by ViacomCBS in June 2020, is reportedly back in production on episodes planned for international territories, according to a news bulletin in the trade magazine Deadline. See Nellie Andreeva, “‘Cops’ Back In Production On New Episodes Following Cancellation,” Deadline, October 1, 2020.

{17} 1986’s Handsworth Songs, by the Black Audio Film Collective, for example, explores a 1985 uprising of mostly Black and brown residents in Handsworth, England through the form of a multilayered text that refuses a singular origin story for the disturbances. Garrett Bradley’s Time, from 2020, offers a more straightforward depiction of a family struggling for the release of an incarcerated loved one, yet yokes its narrative not to courtroom drama but rather the very temporalities of captive life and its reverberations.

{18} Stuart Hall and Bill Schwartz quoted in Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 54.