Strata of Natural History

Jeannette Muñoz

For the Spanish version of this text, please click here.

****

excerpt from STRATA OF NATURAL HISTORY (Jeannette Muñoz, 16mm, color and BW, 11’45”, 2012).

Searching for insistent and invisible traces in Berlin.

The layers do not merge; they are heterogeneous, they antagonize and complement one another. Layers of history, perception, and experience move in circles and in parallel. They are present and absent at the same time. To feel them I must walk these streets myself. I walk and move with the intention of seeing more than my eyes show me, so that places speak to me in different ways. I look out of the corner of my eye to see their ghosts, to see what comes from inside and mixes with what is outside. The connections I intuit become manifest.

Archival images sometimes seem like faint echoes of history.

Searching for what I had read about and seen in books on numerous occasions was the first task I set myself during my stay in Berlin. I saw photographs that had been transformed into sketches, cropped or grouped on the printed page.

It made me wonder about the shape and size of the archive; I wanted to see what it looks like.

When the renowned German physician and anthropologist Rudolf Virchow wrote his anthropological reports in 1881, he referred in timeless paternalistic fashion to “my Fuegians.” Two mug shots per person, one from the front and one in profile, give us evidence of the intrinsic bond between the will to knowledge and the obsession for control and confinement.

I read the name Carl Günther on each one, perhaps the photographer. And a street: Leipziger-Strasse 105, Berlin. A handwritten number and a name: Antonio, Pedro, Lina, Lise, Trine, Henrich, Capitano. Another photo shows a woman with a child. They were probably on display in the Berlin Zoological Garden. On the photo only one name: Grete.

Deprived of her name and identity, a woman arrives in Hamburg in August 1881 aboard a German steamship among eleven adults and children from Tierra del Fuego and Patagonia. The trip has been personally arranged by the zoo entrepreneur Carl Hagenbeck and Rudolf Virchow.

She was not asked permission. Her journey takes place in radical silence. With no translation, with no attempt to explain to her what she will experience, which would be in vain in any case because it transcends her comprehension.

The moment she arrives at the port in Hamburg, she is swallowed up in a colonialist spectacle that has attracted thousands of raucous spectators.

European citizens were invited to visit the botanical gardens and zoos for this enlightening spectacle of natural history. They enjoyed the unquestioning, “self-evident” benefit of witnessing an ethnological event, which, as Virchow said, provided an opportunity to see something of interest and, more importantly, of educational value.{1} The spectators are bursting with curiosity in anticipation of seeing strange and wild human beings who have come from so far away.

Virchow is unable to establish differences between the natives and European citizens despite all his research efforts with living and dead bodies. The collected knowledge gives no evidence.

The natives were then taken on tour to Paris, Berlin, Leipzig, Munich, and Stuttgart. On the way to Zurich, their final destination, the woman becomes increasingly apathetic. She collapses in the freight car. Her eyes close.

Have we ever thought about nonhuman animals?

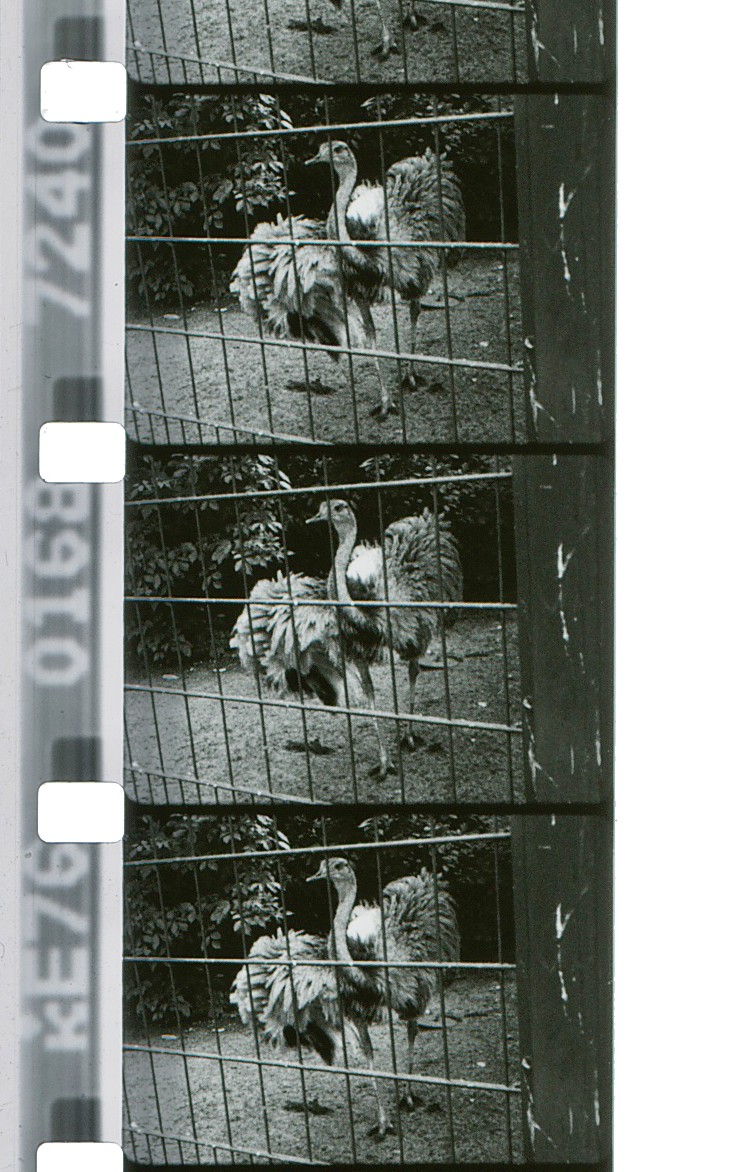

The choike is a bird that lives in Tierra del Fuego. She can reach speeds of up to 60 km per hour. I wonder if the Berlin Zoological Garden has a specimen of her. It does. I find her in a remote corner of the zoo, in a small space where she cannot run. She is silent. No one waits in line to see her. She is rewarded with indifference.

The choike notices my presence and approaches me. I ask if I may film her. Will we be able to communicate across our differences?

At this moment I am not moved by empathy. My camera is not compassionate. Neither are my actions. I am trying to unravel an elusive tangle of connections.

And I do care.

Contemporary zoos no longer exhibit; the word exhibition has been replaced by a more sophisticated euphemism: preservation. But what is actually the objective of zoos in major European cities? What do they want to preserve? We are impressed by the realism of the presentations in a zoo or a museum of natural history and, above all, by the human perseverance that underlies their creation. What was once the colonialist spectacle of natural history has now become the preservation of animals and their habitat, as well as a means of justifying and preserving the institution itself.

Somehow the way in which the choike is presented in Berlin is carelessly honest; the ordinary, understated cage does not pretend to be what it is not. It is simply a poor and naked cage.

The choike averts her gaze and begins to clean her feathers.

Walking through the streets of Berlin I remember the imposing monument Fuente Alemana in Santiago de Chile.

In 1912 the German community in Chile commissioned Gustav Eberlein, one of the leading sculptors of the Berlin school under Kaiser Wilhelm II, to create a monumental allegory of the Republic, of its mineral, agricultural, and maritime riches, and of its workers. The central figure, a powerful man, represents the Chilean people; down below, a native is seen at his side.

In the nineteenth century, the young Chilean Republic directed the stream of immigrants from Europe to the vast native lands south of the capital: biopolitics as an efficient means of seizing native lands. But history does not disappear; its strata always reach into the present. The land conflicts are more intense than ever.

The transformation of the fountain in the Chilean heat of January is a symbolic event. Many families from the marginalized outskirts of the city visit the fountain in the heart of Santiago and transform the dramatic monument into a public swimming pool.

Bathing is forbidden, but not only because of the polluted water. The children take no heed; the sounds and smells of summer are all-pervasive. Peddlers hawk their products. People crowd around the ice cream man. The fountain is their beach. It is hot, and its cascading waters sound like rivers, like waves. Families populate the unkempt lawns of the park. No one seems to hear the noise of the city traffic. The children’s cries are a musical contrast; picnics are already spread out on the ground.

The Berlin Ringbahn

Inhabiting the cinematic experience—inhabiting the process—inhabiting history.

The Berlin Ringbahn is empty. I take a seat next to the window on the right. My camera is attached to a monopod, which I secure firmly between my legs. The film stock is only three minutes long and defines the length of my shots. The editing occurs in the camera. My finger moves to the shutter. I focus to infinity and the train departs.

At the same time that service on the loop began around Berlin’s city center in 1871, Hagenbeck was at work abducting natives from Patagonia. Photographs from the archives give way for a split second to memories of previous trips. Lights, rails, tunnels, stations, trucks, and wagons. A host of impressions. Each change of scene is an unexpected event. Reverberations in the air are mobilized and multiplied. The bright light reflects and produces multiple exposures. Landscapes and urban architecture are monuments to interacting and conflicting forces in an era of European hubris, demonstrated by the indiscriminate displacement of beings and objects: the immense sky reflected here and there, and the horizon of endless industrial complexes, housing, and a panopticon prison as life-forms. The loop circles round and round.

The streets and buildings of the city know, the rivers know, the trees know. When we listen, when we feel or see their pulse, the harmony of the whole that we impose on them crumbles.

Past and future converge. What we can experience are strata of history that are fully transparent and alive. The density of embodied experiences, the abundance of our species and of lives lived, mingle eternally without end, a pure becoming of possible worlds, beautiful and abundant. Everything emerges, and in fortuitous moments it speaks. The world. All we can aim at is that it speaks.

Title video: Strata of Natural History (Jeannette Muñoz, 2012).

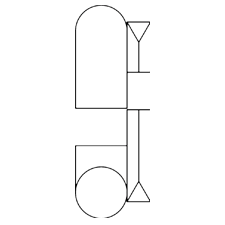

Stills: (1 ) Double exposure of archival photographs of Kawéskar natives in Berlin 1881 and the Zoological Garden. (2) Double exposure of archival photographs of Kawéskar natives in Berlin 1881 and the Zoological Garden. (3) Choike (greater rhea) from Tierra del Fuego at the Berlin Zoological Garden. (4) Bathers in the monument Fuente Alemana (German Fountain) in Santiago de Chile. (5) The Berlin Ringbahn. (6) Double exposure of archival photographs of Kawéskar natives and a park in Berlin.

{1} For much of the information in this article, I consulted the following sources: Rea Brändle, Wildfremd, hautnah: Völkerschauen und Schauplätze, Zürich, 1880–1960; Bilder und Geschichten (Zurich: Rotpunktverlag, 1995); Rudolf Virchow, “Ausserordentliche Zusammenkunft am 14. November 1881 im Saale des zoologischen Gartens,” Zeitschrifft für Ethnologie 13 (1881): 375–94.