Dossier \ Introduction: Documentary World-Making

Josh Guilford & Toby Lee

What does it mean to speak of documentary world-making? Though conversations about world-making have gained currency in film and media studies in recent years, documentary might seem a strange addition to this discourse.{1} Since its inception, documentary has claimed a privileged relation to the world, but the terms of this relation appear inverted or out of sequence when we speak of documentary world-making. Doesn’t documentary name a mode of attending to the world rooted in practices of listening and observation that position the world before the document? As the title of this journal suggests, documentary is supposed to make records of the world rather than the world itself.

Of course, contemporary documentary practice exceeds this definition, encompassing diverse forms of creative manipulation as well as various approaches to media production that seek to effect change in the world. But artists who have historically embraced documentary as a transformative practice have frequently done so while remaining within a representationalist paradigm that ultimately reinforces perceptions of documentary as a medium of record. Whether using media as an instrument of consciousness raising, exposure, or agitation, such practices often valorize documentary’s adherence to the world, embracing its claim to picture a reality that exists outside the cinema. In this paradigm, documentary may make or shape the objective world, but only indirectly, through its representation.

In assembling this dossier, our aim is to consider another way in which documentary practices can be seen as world-making. Rather than looking at how documentaries shape the world through representation, or even at the ways documentarians fashion virtual worlds onscreen, we turn our attention to the social and cultural practices that take place around and through documentary, and which have a more immediate impact on lived experiences of reality and community. The artists featured in this dossier devote substantial energy to conducting workshops, programming cultural forums, archiving media, maintaining technical equipment, and managing organizations; their practices regularly extend beyond the screen to include such activities as education, community building, and cultural preservation. Through such activities, these artists initiate and sustain complex forms of sociality, and contribute to the infrastructure—material and immaterial—of collective life.

Our interest in approaching world-making in these terms is informed by Hannah Arendt’s idiosyncratic understanding of the world, a term she uses to designate the shared environment produced and inhabited by humans, which she divides into two registers: a realm of human artifacts (or what she often calls “the human artifice”), and a realm of human affairs.{2} While the former consists of the total assemblage of material objects—everything from tables to walls, satellites to cathedrals—created through processes of fabrication, the latter consists of the various activities that people conduct between themselves, and includes the quasi-reified customs, habits, manners, and traditions that structure human actions and relations. In Arendt’s view, the world is thus “both material and nonmaterial,” as Ella Myers observes, and though Arendt distinguishes between the realms of artifacts and affairs, she also views these realms as highly imbricated and even mutually constitutive.{3} The main purpose of the human artifice is to house” the realm of human affairs, providing a stable environment in which the perpetual flux of human activities can reliably unfold, and enabling the ephemeral products of action to endure through time in various reified forms (stories, documents, monuments). The man-made world of things is thus integral to the production and preservation of culture, in Arendt’s view. But it is also a precondition for the experiences of recognition and mediation that ground Arendt’s theory of politics. Along with securing a vital space of appearance—a public setting in which individuals can assemble with and gain recognition from others—the human artifice constitutes an objective in-between that offsets the intrinsic subjectivity of human experience.

The objectivity that Arendt associates with the world is one reason we were drawn to her ideas about worldliness. Traditionally, the objectivity of documentary media has been understood in terms of verity, as more or less truthful representations. For Arendt, however, objectivity has little to do with vexed questions of truth. It has more to do with the objectness and publicness of the common world, and the ways in which worldly things condition social and cultural practices, and mediate our relations with ourselves and with others. In Arendt’s work, objects ground perceptions of reality, shape understandings of the past, delimit spaces in which we become sensible to each other, and draw individuals into relation, facilitating experiences of affiliation and community, as well as those of difference and dissensus. The public contexts that objects demarcate—populated as they are by “others who see what we see and hear what we hear,” while still retaining their unique perspective or “location”—can alone convey objective experiences, “assur(ing) us of the reality of the world and ourselves.”{4} This understanding of objectivity as a worldly characteristic can help us to view documentary not as a means for fashioning representations that are truthful to a pre-existing world, but as itself a thing in the world, an object—however multifaceted or intangible—that contributes to the formation and stabilization of public life, enabling and securing crucial experiences of reality, recognition, and commonality. By adopting this perspective, we mean to frame documentary as a variety of what Bonnie Honig refers to as “public things”: the objects that “gather people together, materially and symbolically,” providing a ground “in relation to (which) diverse peoples may come to see and experience themselves—even if just momentarily—as a common in relation to a commons, a collected if not a collective.”{5}

The ideas that structure this dossier emerged from a process of research and collaboration that has manifested in different projects over the past two-and-a-half years.{6} One of these projects was a series of three events exploring questions of world-making in contemporary documentary media culture, which we co-curated in New York City between February-April 2019, and which led to three of the contributions in this dossier.

The first event in this series was a panel and roundtable exploring world-making in contemporary archival practices, which was moderated by Jared McCormick and which featured representatives from three different archival initiatives that deal primarily in documentary media: Diana Allen and Kaoukab Chebaro from the Nakba Archive, an oral history collective which records video interviews with first generation Palestinian refugees in Lebanon; Yasmine Eid Sabbagh and George Awde of the Arab Image Foundation (AIF) in Beirut, which collects and preserves photographs from the Arab world from the mid-nineteenth century to the present; and Christian Rossipal of Noncitizen Archive, a Stockholm-based independent platform for the secure storage of digital video, audio, and photographs from contemporary migrant experiences.{7} While each of these archival initiatives is driven by a deep investment in documentary representations, their relation to the world does not stop there. Many of their defining activities occur in an offscreen space that typically eludes documentary studies, but which reveals an aspect of worldliness at the base of documentary that manifests in such practices as collecting and preserving media objects, documenting personal and communal histories, developing relations within a community, coordinating technical training for volunteers, digitizing collections and designing web platforms, staging exhibitions, and negotiating institutional relations. The energy these organizations devote to these activities speaks to their commitment not only to recording worldly phenomena, but to actively forging and sustaining worldly formations. This commitment animates a range of remarks by participants in “Before, Within, Around, Beyond: World-Making in the Digital Archive,” an edited and expanded transcript of the roundtable discussion, which illustrates the multiple aspects of world-making in which these archives are engaged. By collecting and preserving little-known histories of marginalized communities and making these accessible to broad and variegated publics, the AIF and Nakba enable experiences of connection and commonality that cross historical, geographic, and cultural boundaries. Similarly, by creating physical and virtual forums for refugees, migrants, and other displaced persons to converse and collaborate, Noncitizen brings vital forms of publicness to communities marked by isolation and obscurity. And in their most basic daily operations, all three organizations establish complex webs of relationality between otherwise distant social actors, from state funding agencies and partner institutions to the diverse artists, researchers, donors, activists, and other individuals who contribute to, access, or help to maintain these archives’ holdings. Such webs, always in flux, constitute a key product of these organizations, demonstrating the ability of archives to create as well as preserve.

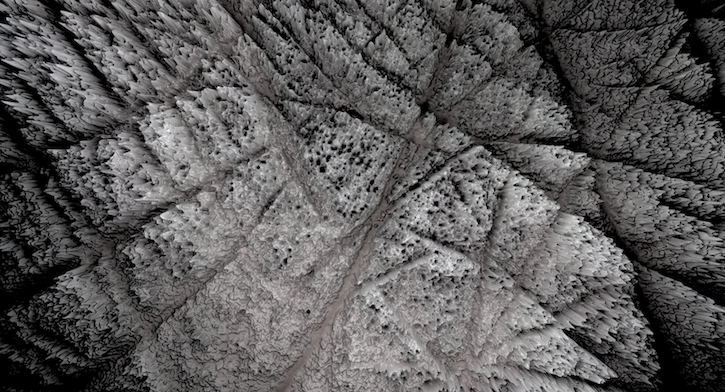

Figure 1. Still from the film series showing the three-dimensionality modelled surface noise of a controversial archival image. FRAME OF ACCOUNTABILITY (Helene Kazan, 2021). Courtesy and copyright of the artist.

Figure 1. Still from the film series showing the three-dimensionality modelled surface noise of a controversial archival image. FRAME OF ACCOUNTABILITY (Helene Kazan, 2021). Courtesy and copyright of the artist.

Another event in the series that centered the worldly capacities of documentary and archival practice was a lecture performance by the artist and researcher Helene Kazan, produced during Kazan’s tenure as 2018-2020 Vera List Center Fellow at The New School.{8} In her work, Kazan often uses documentary modes, whether engaging archival documentary media or producing nonfiction media herself, in order to investigate forms of risk and conflict existing at the potent intersections between architecture, international law, and contemporary art. In the essay “Decolonizing Archives and Law’s Frame of Accountability,” which develops concepts originally presented in her lecture performance, Kazan argues that a decolonizing archival practice can help to reveal, and contest, the reified hierarchies and biases ingrained in international law. Echoing Arendt’s description of the law as an architectural construct assembled to stabilize human affairs, one comparable to the walls that enclose and secure spaces of political assembly, Kazan here frames the law as a world-building technology, but stresses that the violent legacies of colonialism and imperialism continue to inform its architecture.{9} Through discussion of historical case studies, as well as her own research and artistic work concerning the twentieth-century history of colonial and state violence in Lebanon, Kazan argues for an oppositional approach to the archive that aims to illuminate hidden and suppressed records of colonial violence, and to counter the influence that official colonial histories continue to exert on the practice of international law. Yet Kazan also emphasizes the need for critiques of international law that bring together poetic and forensic resources. Presenting the concepts of poetic testimony and legal fiction, which she uses in her work, Kazan proposes the realm of cultural production as an alternative legal arena, one in which creative practice can challenge, disrupt, and intervene in the dominant structures of the given world.

Completing the event series was a roundtable on Black women’s cinema, co-organized with members of the New Negress Film Society (NNFS), a Brooklyn-based production collective that centers the work of Black women and non-binary filmmakers.{10} The roundtable brought members of the NNFS together in conversation with participants from the inaugural Black Women’s Film Conference, an event produced by the NNFS at MoMA PS1 in March 2019. With this event, our aim was to expand the frame of the series by considering artistic organizations and creative practices that are imbricated with or adjacent to traditional forms of documentary media, but which are not strictly defined around documentary. The NNFS is a core collective of Black women filmmakers who work across different media and genres, including documentary. But their priority is to create community and spaces of support, exhibition, and consciousness raising around the work of Black women and non-binary artists. Through diverse activities that range from fundraising to organizing workshops, programming films, and conducting interviews, members of the NNFS work collectively to create spaces of recognition and networks of support for artists marginalized by the industry, striving in this manner to alter the material and social conditions under which they work. In “Another Table: Black Women’s Cinema and the Production of Community,” an edited transcript of the roundtable, participants discuss the many entrenched biases, material obstacles, structural inequalities, and restrictive conventions they have confronted and transformed in their fight to create media on their own terms. They also emphasize the labor they devote to forging communities of care and forms of mutuality and collectivity that diverge dramatically from the relational customs and structures governing the commercial film industry. In their discussion, and particularly their remarks on the possibility of changing existing systems of production, we hear echoes of Arendt’s famous metaphor of the world as table—something that “is located between those who sit around it . . . relat(ing) and separat(ing them) at the same time.”{11} Examining the oppressive and liberating capacity of such mediating constructs, the artists featured in this contribution debate whether it is better to have a seat at the table, to try to re-shape that table, or to build another table altogether.

Figure 2. Members of the NNFS at the Black Women’s Film Conference on March 17, 2019, MoMA PS1. Photograph by Derek Schultz.

Figure 2. Members of the NNFS at the Black Women’s Film Conference on March 17, 2019, MoMA PS1. Photograph by Derek Schultz.

Rounding out the dossier are two essays composed specifically for publication in World Records, both dealing with organizations that, like the NNFS, are not strictly centered on documentary but that model the world-making capacities of media in ways that challenge and provide critical perspectives on documentary’s representational paradigm. In “The Abominable Community: Notes on Independent Filmmakers’ Laboratories,” Mariya Nikiforova examines the movement of independent photochemical film laboratories that has taken shape over the last two-and-a-half decades, largely in response to the commercial film industry’s digital conversion. As Nikiforova explains, though this movement was initiated in Francophone Europe as a relatively modest experiment in DIY filmmaking, it has since expanded into an international network of artist-run workspaces that are reorganizing the infrastructure of photochemical filmmaking in artisanal terms.

Focusing on a single lab within this network—L’Abominable, located on the outskirts of Paris—Nikiforova argues for the importance of approaching independent laboratories as political rather than simply aesthetic endeavors. In her view, the anarcho-socialist principles that seem to animate L’Abominable help us to see the independent laboratory as “a proposal for a particular kind of community,” one oriented not only toward filmmaking but toward the production and maintenance of a cohesive “form-of life,” or a way of living that strives to “unify social, creative, political—and even, possibly, biological—aspects of life into a continuous whole.” For Nikiforova, this utopian ideal is evident in L’Abominable’s efforts to integrate photochemical film systems into a non-hierarchical organizational structure that necessitates resource sharing, collaboration, and self-education, and which values filmmaking as much for the social relations it facilitates as for the aesthetic objects it produces. Yet L’Abominable’s interest in cinema as a communal medium can also be discerned, she argues, in its commitment to preserving, maintaining, and re-designing the material objects, mechanisms, and processes that enable photochemical filmmaking, which are increasingly rendered obsolete by digitization. As Nikiforova explains, this commitment reveals L’Abominable’s investment in elaborating a sustainable, collectivist model of cinematic practice consistent with the ethical and political principles held by many of its members. What Arendt would term the “attitude of loving care” that this organization displays toward worldly things can thus be understood as a sign of its resistance to the world-eroding tendencies of consumer society, which Arendt considered detrimental to public modes of action and affiliation.{12}

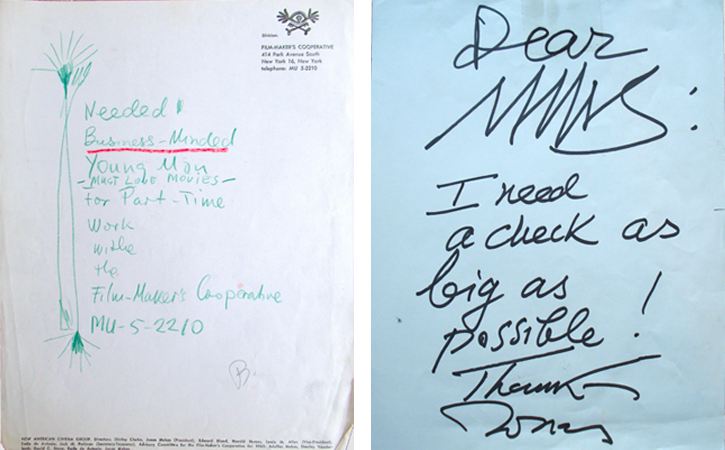

A related emphasis on the world-making ambitions of alternative film movements can be found in the final contribution to this dossier, Josh Guilford’s “Disorganized Organization: Signs of Life in the Film-Makers’ Cooperative’s Paper Archive.” Guilford’s essay examines a complex interplay between worldliness and vitality—or what Arendt would term zōē, a form of life affiliated with natural and biological processes—that structures the paper collections of the Manhattan-based experimental film distributor, the Film-Makers’ Cooperative, which was founded by members of the New American Cinema (NAC) in 1962. Positioning this interplay as a symptom of the NAC’s simultaneous desire for, and aversion to, cultural stability, Guilford demonstrates how these competing impulses play out in the history and operations of the Coop, as well as the structure and contents of the Coop’s paper archive. As he argues, Arendt’s view of documentation as a form of reification—the mechanism whereby vital processes and events are transformed into dead objects, such as archival records—helps to explain the NAC’s ambivalence about documentation, which manifests in the Coop’s paper archive at multiple registers. As an avant-garde formation governed by ideals of vitality, spontaneity, and immediacy, the NAC struggled to evade the deadening effects of reification at every turn, even as the artists affiliated with this movement sought to elaborate a durable, alternative culture anchored in institutions like the Coop and documented in expansive collections of paper records and audio-visual media. Focusing on the tensions that resulted from these seemingly contradictory impulses, Guilford explores the legacy of the NAC’s desire for a “world without worldliness.” Rather than assessing documentary filmmaking, his essay considers the worldly dimensions of the document more generally, and the ways in which practices of documentation and archiving function as crucial testaments to alternative world-making projects.

Figure 3. Ephemera from the Film-Makers’ Cooperative’s Paper Archive. (L) “Needed Business Minded Young

Man – must love movies – for Part-Time work with the Film-Makers’ Cooperative.” (R) Dear MMS: I need a check as big as possible! Thanks, Jonas.”

Figure 3. Ephemera from the Film-Makers’ Cooperative’s Paper Archive. (L) “Needed Business Minded Young

Man – must love movies – for Part-Time work with the Film-Makers’ Cooperative.” (R) Dear MMS: I need a check as big as possible! Thanks, Jonas.”

The framework of this dossier is thus structured primarily around organizations, and is meant to highlight the crucial role that film and media organizations play in catalyzing and sustaining alternative cultural formations. As a whole, the dossier connects the otherwise disparate set of organizations assessed in these contributions by positioning them as testaments to the world-making capacity of film and media, committed as these organizations are to building and maintaining the material and social infrastructure that makes worlds out of emergent or marginal forms of collectivity. At the same time, these conversations and essays seek to raise complex questions about the value and function of worldly stability. Even as the artists and organizations featured herein exemplify the radical potential of world-making activities, the various forms of work they conduct also reveal the restrictive and oppressive components of worldly constructs, as well as the difficulties that alternative cultural formations confront when they strive to contest the dominant world’s reified structures.

In the process of discussing the different approaches to refashioning the world, or forging new ones, that manifest across these materials, we have returned repeatedly to John Grierson’s seminal definition of documentary as the “creative treatment of actuality.” This phrase is usually understood, as it was intended, to specify the work that documentary performs at the level of representation, designating documentary’s aesthetic treatment of sounds and images of the world. But in their efforts to create and sustain community, to reshape the conventions that organize film and media practice, to stabilize and preserve alternative ways of life, and to otherwise build the worlds they want to inhabit, the artists and organizations featured in this dossier suggest another possible interpretation of this phrase, modeling a creative treatment of actuality that takes the world itself as its terrain. Following their model, we end by asking whether the expanded creative practices in which these artists and organizations are engaged could be applied productively back to understandings of documentary. What if the point of documentary is not to represent the world, but to make it?

Title Video: Images from the Arab Image Foundation

{1} For recent discussions of world-making in cinema, see especially: Daniel Yacavone, Film Worlds: A Philosophical Aesthetics of Cinema (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015); Karl Schoonover and Rosalind Galt, Queer Cinema in the World (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016); and Claudia Breger, Making Worlds: Affect and Collectivity in Contemporary European Cinema (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020). Earlier analyses of world-making in cinema studies include: David Bordwell, “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative” in Poetics of Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2008); and Suzanne Buchan, ed., Animated Worlds (Herts, UK: John Libbey, 2006).

{2} Arendt elaborates on her understanding of world most extensively in The Human Condition, Second ed. (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press , 1998), esp. ch. 4 (on “Work”). The duality underlying this concept can be seen, for instance, in an important passage from this work, in which Arendt distinguishes her definition of world from the more natural and terrestrial connotations that sometimes accompany this concept: “(The) world . . . is not identical with the earth or with nature, as the limited space for the movement of men and the general condition of organic life. It is related, rather, to the human artifact, the fabrication of human hands, as well as to affairs which go on among those who inhabit the man-made world together” (52). She expands on these remarks later in The Human Condition, writing: “(T)he physical, worldly in-between along with its interests is overlaid and, as it were, overgrown with an altogether different in-between which consists of deeds and words and owes its origin exclusively to men’s acting and speaking directly to one another. This second, subjective in-between is not tangible . . . (but) is no less real than the world of things we visibly have in common. We call this reality the ‘web’ of human relationships, indicating by the metaphor its somewhat intangible quality” (182-3). For an interesting assessment of Arendt’s phenomenological account of this duality via D.W. Winnicott’s object-relations theory, see: Bonnie Honig Public Things: Democracy in Disrepair (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), esp. 37-57.

{3} Ella Myers, Worldly Ethics: Democratic Politics and Care for the World (Durham, NC: Duke University Press , 2013), 89-90.

{4} Arendt, Human Condition, 50. See also pp. 57-58.

{5} Honig, Public Things, 16. Honig borrows this distinction from Michael Oakeshott.

{6} The first of these was “‘In the Presence of Others’: Revisiting Hannah Arendt in Film and Media Studies,” a panel presented at the annual conference of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies, Toronto, Ontario, March 14-18, 2018. We are grateful to Bonnie Honig and Nicholas Gamso for their participation in this panel, which shaped the framework of this dossier in significant ways.

{7} “Archival Worlds: Documentation, Preservation, and Digital Media in the Middle East,” Hagop Kervorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies, New York University, New York, NY, February 21, 2019.

{8} Helene Kazan, “Speculative Legal Futures and the Poetic Testimony of Violence,” UnionDocs Center for Documentary Art, Brooklyn, NY, April 4, 2019.

{9} See Arendt, Human Condition, 194-5.

{10} Roundtable on Black Women’s Cinema, UnionDocs Center for Documentary Art, Brooklyn, NY, March 16, 2019.

{11} Arendt, Human Condition, 52.

{12} Arendt, “The Crisis in Culture: Its Social and Its Political Significance” in Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought (New York: Penguin, 2006), 208.