Bidayyat \ A Link, Courier, or Smuggler between Generations: Interview with Ali Atassi

Stefan Tarnowski

Stefan Tarnowski

I organized the questions to start by discussing you personally: who you are, your very specific story, some of which you shared in an article that came out at the beginning of the Syrian revolution, written for the New York Times{1}—

Mohammad Ali Atassi

As a journalist, and also somebody who always likes to critique others, I have a problem with your first question. Like everyone, I find it difficult to talk about myself personally. First, I prefer to place myself in context, not to focus on the individual. And second, you refer a lot to an article, which is the first thing that comes up when you google my name. But I’ve written a lot in my life, especially between 2000 and 2010. The majority of those articles aren’t online. I wrote one or two articles a month for ten years, sometimes more, and often very long articles. Most were about the question of rights and freedoms, the role of the intellectual in the public sphere, the question of Islam, tradition, and the Enlightenment; they also included frequent references to cultural production, and specifically film and poetry. So, I have a problem with your opening questions. But it’s OK, if you want to ask, ask, and I’ll answer as best I can.

ST

I wanted to begin with the question of generational politics. I know that in the list of questions I sent you, I start by referring to the New York Times article, and maybe that is too obvious a place to start. But it’s also one of the most obvious things about you, which is that you’re the son of Noureddin al-Atassi, who was the president of Syria before Hafez al-Assad took power in a coup in 1970, and who was imprisoned by Assad. So, you have a very personal generational relationship to the struggle against the Syrian regime.

AA

I feel that this is the worst misunderstanding possible of me, for one reason alone: I was two and a half years old when my father was imprisoned. And he was imprisoned for twenty-two years—effectively for my whole life—until I was twenty-four years old. He was imprisoned for one reason only, which is that he was the president. And while he may have officially been president, he had also submitted his resignation and refused to cooperate with Hafez al-Assad’s coup. The price of refusal was twenty-two years of imprisonment. I’ve never considered myself the son of a president; I’m the son of a political prisoner. The very idea of being the “son of a president” is meaningless to me.

I always repeat a quote by the French theorist Guy Debord to anyone who wants to classify me as the son of a president: “People resemble their times more than they resemble their fathers.” Of course, this won’t prevent me from saying that for me my father is the dearest and noblest person I have met in my life, and that I am full of respect—and criticism—for his experience, for better or for worse. Especially the fact that he paid a heavy price for his political commitment, and for his insistence on his principles.

I was living in a country—Sūriyā al-Assad, Assad’s Syria, as the regime calls it—in which even mentioning my father’s name was forbidden; in which my father was imprisoned, and we couldn’t even say why he was in prison. He was imprisoned for twenty-two years without trial, and without charge. He was a prisoner of conscience. Every fortnight, I would visit my father for one hour in prison, in Mezze prison, which is a horrific place. So, I really did live the life of prison, repression, censorship, dictatorship, and the annihilation of the individual, which are fundamental aspects of the Assad regime.

That is also the life of our generation, by which I mean a generation of Syrians born after 1967. As a generation, we lived one of the ugliest and hardest periods of Syria’s history for a number of reasons. The country was becoming more and more closed. Hafez al-Assad was not just a dictator, but was implementing National Socialist policies: he was trying to build a dictatorship around himself. We lived the militarization of school life. We were forced to join the Baath Party youth wing, Ṭalā’i’ al-Baath [the “Vanguards of the Baath Party,” the National Organization of Syrian Children]. I was conscripted into the organization like everyone else in my school year and everyone else in my generation. After Vanguards, we lived something called Shabībat al-Thawra [Revolutionary Youth], which spanned from grade 7 until the end of high school. The ugliest period was the time of Rafaat al-Assad’s Defense Company “paratroopers” [mudhaliyin wa midhaliyāt], the militia group run by Hafez al-Assad’s brother. In second grade, you could join to improve your grades. Joining these groups made it easier to get a place at university. The price was being trained in a militia. I saw my schoolmates going away for paratrooper training, coming back wearing paratrooper uniforms, and getting better grades as a result. Later, I also lived the militarization of university life. I studied in the department of civil engineering. I had decided not to leave Syria for university; my father was imprisoned and I wanted to be nearby. I witnessed military training taking place within the university.

Assad’s Baath Party and its policies developed a personality cult, especially following a visit he made to North Korea in 1974. The cult aimed at the annihilation of the individual, and tyrannized the entirety of the public sphere, including the education system. This meant that any form of political criticism would result not just in prison or death, etc., but in a sense of transgressing the sanctity of political power. For this and because of this, transgression in the “Kingdom of Silence,” to use Riad al-Turk’s phrase, was possible but costly in terms of human suffering. Lisa Wedeen has theorized all this very fully in Ambiguities of Domination (1999). But it was something I lived from the inside, not in theory. Unfortunately, those theories were also unable to account for the Syrian revolution, which, as with all the revolutions of the so-called Arab Spring, was an earthquake that destroyed the system we were trying to understand from its very foundations. It made our past theoretical models obsolete. The old paradigms were no longer able to keep pace with new methods of protest, expression, and rebellion that were born outside the umbrella of the authoritarian state and its institutions.

ST

Before we get to Bidayyat, can we talk about your work between 1992 and 2011? Your father was denied medical treatment until about a week before his death, when he was allowed to travel to France, where you joined him and tried to document his memories and experiences. We’ve spoken before about the sense of loss you felt at never being able to document him talking about his life and experiences, and how this impacted your later work collecting the testimonies of political prisoners in your writing for the Mulhaq al-Nahar as well as in your filmmaking. After your father died, you stayed in Paris. Although you had a BA in engineering, you decided to change tack: you spent a transition year studying urban sociology at the EHESS, and finally switched to studying history at the Sorbonne. You didn’t finish your PhD thesis because you moved to Lebanon and began covering the 2000 Damascus Spring as a journalist, and you also actively took part in the political salons or forums [muntadayat], organizing the logistics and composition of various well-known statements and petitions by prominent Syrian militants and dissidents, such as the “Statement of the 99” and the “Beirut-Damascus Declaration.” In our first conversation, you described liaising between an older generation of dissident political prisoners and your own younger generation by saying you acted as a passeur entre les générations, a smuggler between generations. During that period, you also made what’s perhaps the first documentary from Syria recorded on a handheld digital camera. You returned to Damascus in 1999, just before Hafez al-Assad died, and published a series of long interviews with Riad al-Turk, and afterward you ended up making a film about him, Ibn al-Am (2001). I also heard that perhaps the only moving images that still exist today from the political salons during the Damascus Spring are in Ibn al-Am. Which forum were you involved with during the Damascus Spring?{2}

AA

I’ll come back to the notion of a passeur later. But first, I wasn’t involved exclusively with one particular forum. I was writing for Mulhaq al-Nahar [the weekly cultural supplement for the Lebanese daily newspaper Al-Nahar], which was edited at the time by Elias Khoury, the Lebanese novelist. The supplement responded to the specific cultural and political situation in Beirut at the end of the 90s and the beginning of the second millennium. But unlike friends who were journalists, I wasn’t a full-time employee. I had more freedom to choose my topics, and to write long articles, which allowed me to expand on whatever topic I chose. For the Mulhaq al-Nahar, I did a lot of interviews, especially with everyone being released from prison during this period. No one dared speak. I did an interview with the poet Faraj Bayraqdar about Tadmor [Palmyra] prison. I did another one with Riad Seif, Riad al-Turk, and Antoun Makdissi; I wrote a long article about Mezze prison when it was finally shut down. The articles also responded to and catalyzed debates taking place in Syria during that period on issues such as human rights, prison, freedom, and political rights.

When the Ayloul Festival was established in 2000—which was the first contemporary art festival in Lebanon, with events linked to cutting-edge artists and filmmakers like Jayce Salloum, Akram Zaatari, Rania Stephan, Walid Sadek, Rabih Mroueh, etc., who were all doing video art, installation, performance, and working with small digital cameras—Elias wanted to invite Faraj Bayraqdar to give a poetry reading here in Beirut. But he couldn’t travel, and since I’d already interviewed him, Elias Khoury and Pascale Feghali, the heads of the festival, gave me a small camera and asked me to record an interview with him. Faraj had just been released from prison after eighteen years. He was living just north of Homs, where my paternal family is from, and I went and filmed an interview. But on the way I decided to stop at Riad al-Turk’s place in Homs, and I pressed record. That’s how the idea came about. I decided to make my first film about Riad al-Turk instead, at a moment when he had been banned from leaving Syria after his release from prison in 1998. I’d done long interviews with him for Al-Hayat and the Mulhaq, but I felt that there was something going on around him, a forum forming, a debate that had to be documented. I simply took the small camera across the border and filmed for four months, and then returned to Beirut with the rushes on small DV tapes.

Ossama Mohammed and Omar Amiralay had also wanted to make a film about Riad al-Turk. They had made films about Fatih Mudarris, and about Shabandar, the founder of Syrian cinema. They had planned to start filming around the same time, then they stopped for various reasons. I told Elias Khoury I wanted to make the film they’d commissioned about Riad al-Turk instead, using the small camera he’d lent me. Together with Loubna Haddad, whom I asked to join me on this adventure, and whose father, the journalist Rida Haddad, had died of cancer while a political prisoner like my father, we filmed Riad al-Turk over the course of four or five months. The whole thing was done surreptitiously, with just that small camera. And then during the Jamal al-Atassi Forum in Damascus, when Riad al-Turk spoke in the spring of 2001, I just sat in the front row with the camera and pressed record. I didn’t ask for permission.

The film documents a very particular moment: Riad al-Turk had been released from prison, and he was restarting his political activism. Hafez al-Assad had died, but Bashar al-Assad hadn’t yet solidified his dictatorship. The regime didn’t know what to do. Loubna and I were young, we weren’t yet thirty-five years old. We were going around with our small digital cameras and filming, never bothering to ask for permission, never working with the National Film Organization (NFO). It was all very low-budget. I think, if I’m not mistaken, it’s one of the first Syrian films shot on a small digital camera, made ten years before the Arab Spring. There was no YouTube at that time, but I uploaded it there later, after the revolution started in 2011. At first it was distributed on CDs and DVDs. It felt like the idea of the pamphlet, the tract, had shifted onto the DVD. It’s very interesting. Now there are neither CDs nor pamphlets, it’s all online, and you need a VPN . . . These technological shifts are interesting.

IBN AL-AM (Mohammad Ali Atassi, 2001). Courtesy of the filmmaker.

ST

They sound like exciting days.

AA

Yes, but they were difficult; there were people in prison, a lot of suffering—many of them are still in prison to this day. And it was the start of all the brutality that began after 9/11, which was a turning point.

ST

Last question about your work as a director pre-Bidayyat. I’ve heard your work as a filmmaker described as driven by a desire to find a father figure. You establish intimate ties with your main characters, which is one of the great strengths of your filmmaking method and style. But the other side of the coin is that as well as making these generous, intimate portraits, you often end up in raw confrontation with the spiritual father. Is there a contradiction in your work: to find the father figure and to kill the father?

AA

I agree. I wasn’t completely conscious about that, but when I watch them together and see these moments of tension, there’s definitely a common thread relating to father figures, as well as to the human relationship with political liberation, religious liberation, social liberation. Those things are all present.

But there’s an important difference with regard to Our Terrible Country (2014). I think that the problematic relationship with a spiritual father took place between Yassin al-Haj Saleh and Ziad Homsi, and this allowed me to think about the structure of this relationship partly from the outside, so to speak.

What bothers me today, when I rewatch my films, is that all the main characters are men, and they all have the same profile or status as intellectuals or political figures. I hope in my future films, if they are going to be about any kind of figure, then they become about women. It’s time.

****

ST

OK, so let’s begin again in 2011: the Arab Spring begins, protests . . .

AA

At the start of the revolution, on the first day of the revolution, on March 18, I arrived in Paris from Beirut. I’d been in Syria and my plane landed at 2 p.m. Sonja [Mejcher-Atassi], my wife, called me and said they’re protesting in Deraa, they’re protesting in Homs, and I started weeping. As I went through passport control, they didn’t understand why I was crying. I was so moved, March 18, 2011. The day I arrived in France I spoke about revolution on the satellite channel France 24 in Arabic and in French.

It was the moment we’d been waiting for for decades. You can’t imagine what it felt like when the young men and women started coming to Beirut, and I wasn’t able to go to Syria. So I thought, How can I help? At first, I tried to help by writing and organizing media access for young people inside Syria. Then with Layla Al-Zubaidi from Heinrich Böll, we tried to send cameras and satellite phones.

We said we can’t do only that, but what we can do is to train young activists to make TV reportage and documentary films. At that time in Beirut, I got to know some young men and women from Syria, such as Reem al-Ghazi, Joude Gorani, and Kinana Issa, who were involved in the revolution and were interested in creating a media and cinematic institution that would help and train young activists. That was the foundational idea behind Kayani. We set up Kayani in March 2011 with the support of the Heinrich Böll Foundation. In fact, we did the fundraising externally, but Heinrich Böll gave us legal cover. We started organizing workshops and making short films using footage taken by young people in Syria.

But sitting in Beirut we didn’t have any control over what was going on. We didn’t know who the activists were, we didn’t know where the footage was coming from sometimes, and we couldn’t use their names. We were also trying to show the peaceful and civic face of the revolution. We organized workshops here in Beirut, and then activists would go back to Damascus.

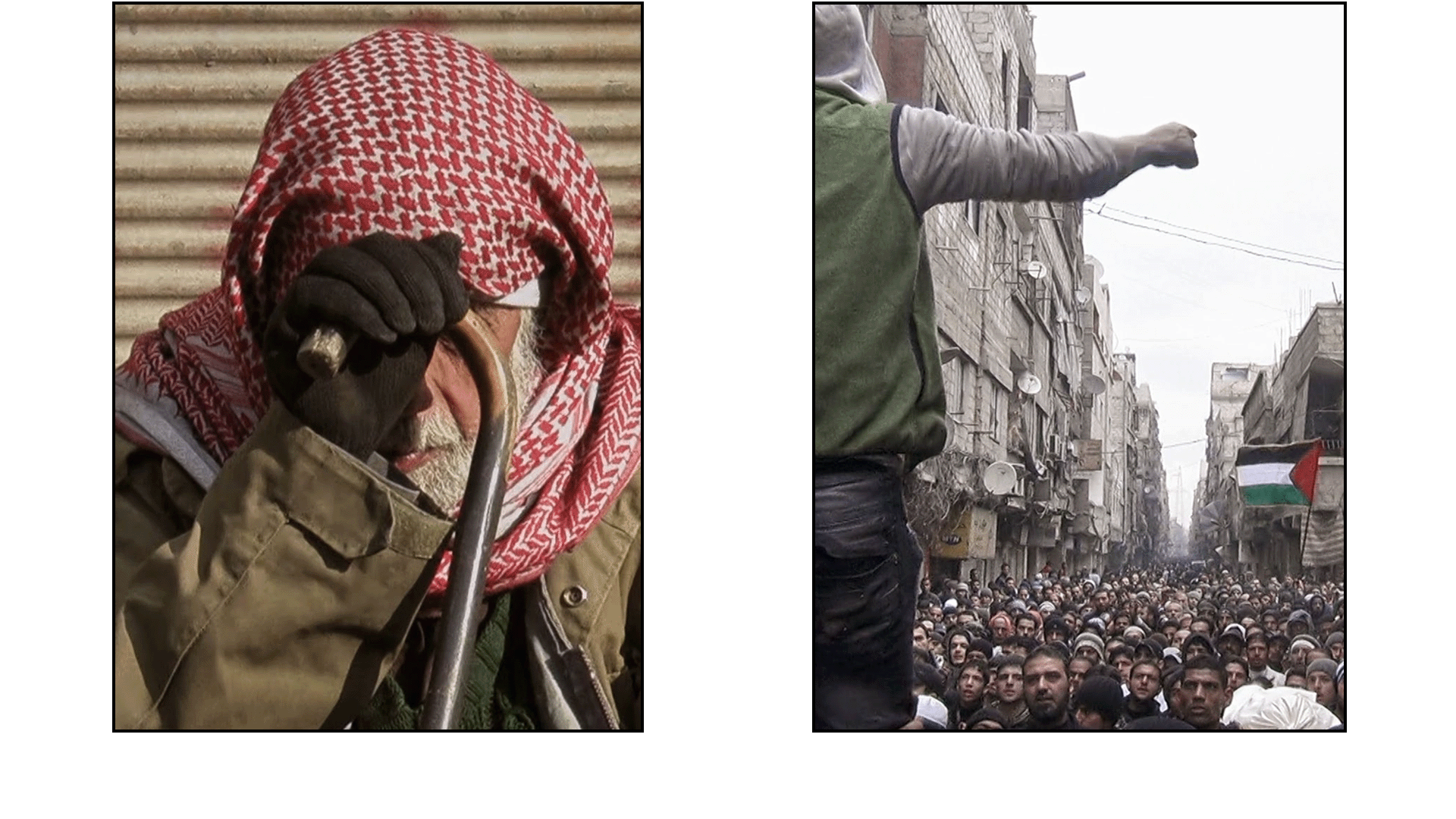

Frame grab of cellphone footage from the streets of Deraa, Syria, broadcast by France 24 on March 19, 2011.

Frame grab of cellphone footage from the streets of Deraa, Syria, broadcast by France 24 on March 19, 2011.

ST

Then at the end of 2012, Kayani was dissolved as an organization, and you were in the process of founding Bidayyat, which launched in 2013. Immediately, Bidayyat focused more on experimental or creative documentary, and less on activist clips and reportage.

AA

My time with Kayani came to an end after about a year, for several reasons that I won’t go into here because they don’t concern me alone, and it’s not only my story to tell. It became clear to me how important it was in the middle of the revolution to create space for auteur cinema and for artistic creativity. Questions of authorship and copyright also began at this point, questions I returned to in the debate in Al-Jumhuriya with Yassin al-Haj Saleh: who’s filming, why are they filming, what are their rights, and what are the rights of the person being filmed.{3} All these questions began during this period, and they’re still relevant.

These questions and ethical issues were a push toward making films that focused more on cinema, on films made by individuals, with their own points of view, with their particular creative process, while at the same time addressing global issues through these films—but making sure that we weren’t just making propaganda. I also wasn’t alone at Bidayyat—from day one Christin Lüttich was there, alongside Joude Gorani, Rania Stephan, and others.

ST

Can I ask about that anxiety between generations, if it’s possible to speak in those terms: Was one of the fundamental issues that the young activists involved in Kayani weren’t interested in cinema, and that you brought in the idea of authorship and cinema?

AA

No, and it wasn’t a tension between generations, in my opinion. If you look at the young people with whom Bidayyat worked, their interests are all clearly in cinema and documentary. We could help train filmmakers if they wanted to make films. But training journalists and telling them what to do, while news agencies were paying them thousands of dollars, and trying to create an alternative news platform in a field where Al Jazeera, Al Arabiya, Reuters, the regime’s media all already existed . . . That’s a bigger game, and we couldn’t compete.

Through art and cinema, we shifted focus to the individual and the personal. We could ask questions rather than provide answers. We were still engaging with images, but in a very different way. It’s like comparing writing poetry or a novel with writing a news article. It’s not the same.

ST

I remember at the start of the thawra in Lebanon in 2019, we all got together downtown in Samir Kassir Garden, organized through a WhatsApp group, “we” being the cultural scene in Lebanon. During the discussions, a consensus quickly emerged that this wasn’t the time for art; it was the time for revolution. I often think about that moment and how different it was from the Syrian revolution, when the alternative art scene, the intellectuals, and the cultural scene all recognized that even if they weren’t the center of the revolution, they should join, integrate themselves, and work with the tools and skills they had. Did you notice that difference between Syria and Lebanon? Why was there less of a gap between revolutionary work and artistic work in Syria?

AA

At the start of the Syrian revolution, all the focus was on revolutionary work and not on art. I often ask myself about the importance of Syrian cinema and documentaries, specifically about the relation between the importance of Syrian cinema and the scale of the disaster that Syria has faced, the reality on the ground. True, documentaries from Syria have won important prizes. But I also often think about the surrounding problematics. Was it just the case that the reality on the ground was so difficult that Syrian documentary cinema, which is inherently connected to that reality, will inevitably play a prominent role? In my opinion, no.

In 2010–11, it wasn’t just Syrian reality that exploded. There was a whole Arab Spring, which was linked to an explosion of generational creativity. There was a generation completely different from my own, who didn’t have a language in which to express themselves, and who didn’t find themselves reflected in the poetry of Nizar Qabbani, or in pan-Arabism, or in political Islam. That generation was sitting there, forbidden from talking, marginalized, then suddenly occupied this huge space of freedom. It was a very particular moment. There was this huge explosion of creativity.

Another important point was that the Syrian revolution and the Arab Spring came at a turning point in terms of social media—YouTube, Facebook, uploading, etc. Since the state banned international media access to Syria, there was no foreign access to that reality; this doubled the importance of social media in Syria. All these elements, along with digital cameras and the democratization of equipment, created the conditions of possibility for a Syrian documentary cinema invested in new creativities and new languages. There were also disasters and failures, some of which you’ve written about. But there are important moments. Bidayyat, I think, was among those important moments. If I were to try to found Bidayyat today, I wouldn’t be able to do what I was able to do—there were all those objective conditions in place.

There’s another important thing. There were also questions and problematics that were being posed for the first time in the history of documentary cinema with such clarity. For example, because of the lack of access to places where events were happening, directors would ask others to film for them. When those other people were filming, the director wasn’t watching everything at a distance through a screen and giving directions from afar about what to film next. In these situations, the DOP began to play a role resembling a director, as well as a fixer, as well as a sound recordist, all on top of being a DOP. That person could decide what was included in the frame, when to press record and when to stop recording, what questions to ask, whether to pursue a line of questioning, when to stop asking altogether. All of those tasks are the tasks of a director! These conditions created a new set of questions, and sometimes the answers to those questions were exceptionally bad. Sometimes they were incredibly good. At the center was the question of who is filming and for whom. It’s an extremely problematic issue. It’s not just an ethical question. In its essence, it’s a filmic question. And it was a question that really imposed itself with the situation in Syria.

There’s another question I always ask myself, which I think might be helpful for someone who wants to work on the subject of Syrian documentary cinema, or more broadly even, on the question of whether there was a digital or social media turning point in relation to Syria. It’s a methodological question, but I think it’s important. Why documentary cinema—as a genre, as an art form, as a form of mediation—why did it play such an important role in Syria throughout these years? Personal narratives are of course important for understanding Syrian documentary or Bidayyat. But more important than narratives and discourses about agents and actors is a sociological analysis about how this moment was constituted, and how its agents are constituted through this moment. It’s not enough to simply say that it’s because documentary cinema deals with reality and reality has surpassed anything a fiction might have imagined for Syria. That’s important, but it’s not the only reason, and it’s necessary to do some digging to think through the other reasons.

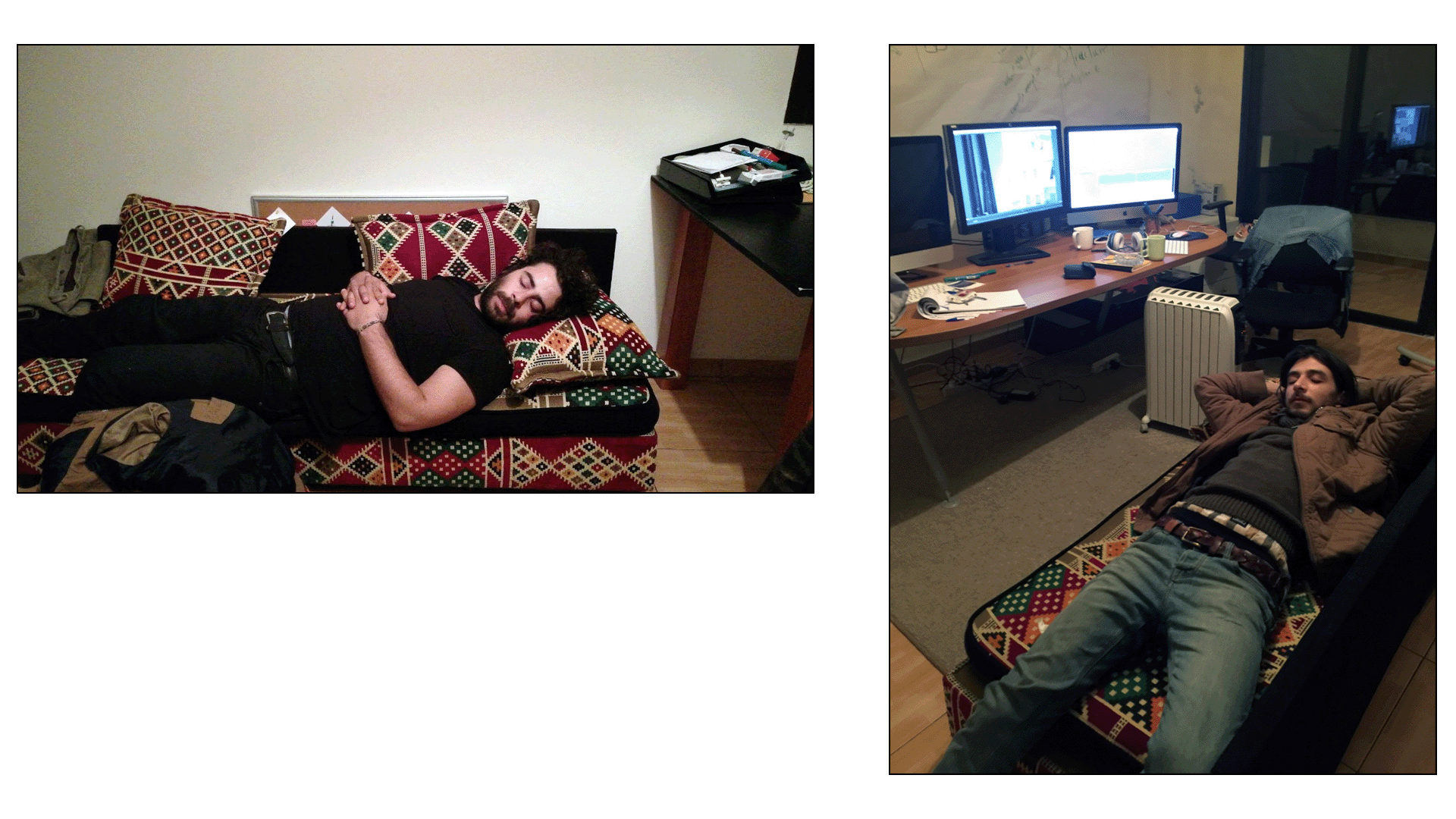

Production workshop at the Bidayyat offices in 2018.

Production workshop at the Bidayyat offices in 2018.

ST

Can I ask a different question? In the first years of the revolution, what kind of future were you dreaming of or imagining for the country? What kind of political system, what kind of justice, and how was it related to the establishment of Bidayyat?

AA

When we did workshops with our young participants, we asked the question a lot. But don’t make the mistake of thinking that I’m Bidayyat’s spokesperson, someone who’s able to say outright that these are our dreams, or this is our program, etc. That’s not how it worked. There’s no doubt that from the beginning of the revolution, our participants fit a kind of ideal type. They definitely weren’t with the regime, they wouldn’t defend the regime narrative, nor was their discourse that of radical Islam. Their choice of subject matter flowed from the way they as young people lived their lives, and from their way of talking to others. It was linked to the kinds of civic activism associated with the Local Coordination Committees (LCCs) forming across the country, and with the Arab Spring more generally. All the young people talked about dignity, freedom, equality, etc. And these weren’t ideas invented by us; they were prevalent, and they intersected with what a lot of young people were saying in Egypt, Tunisia, and elsewhere. So, the subjects we worked on, the people we worked with, and the places we were in all overlapped based on these shared ideals and interests.

ST

Was Bidayyat attempting to perpetuate the virtues of the revolution, even amid defeat?

AA

Yes, but that doesn’t mean we were simply reproducing a political discourse. Let me give you an example: Avo Kaprealian’s film Houses without Doors (2016). Avo was never a supporter of the Free Syrian Army. He’s an Armenian from Aleppo whose own family was being shelled by the Free Army. But he felt a real sense of sympathy with the displaced, and was trying to read the Syrian tragedy within a larger tragedy of violence, civil war, displacement, and massacre extending all the way to the Armenian genocide. Avo’s narrative thread meant he never said outright that he was with the revolution—even though at the beginning of the revolution, he participated in and filmed protests. And he was always true to his own story. He also never defended the regime or its crimes. Even on the question of the Armenian genocide, he never made nationalist propaganda. And I never came and told him what his politics should be. It’s an example that gives an idea of the diversity of our participants. That’s also why you should watch Yaser Kassab’s film I have seen nothing, I have seen all (2019). A shell from a mortar attack launched by the Free Syrian Army killed his brother. It landed on the balcony of their house in a regime-controlled area of Aleppo. There are people—some of whom brought their footage to us at Bidayyat—who stood around filming mortar attacks on Damascus fired from Ghouta, or who launched shells from one side of Aleppo to the other. This is just another example of the kinds of proximity, or the two-sidedness, of the work we did, and who we worked with.

ST

This position that you’re describing is fundamental, I think, for someone to live in dignity in this region. It’s the position of multiple refusals, of refusing to choose between two or more bad options: refusing both the regime, radical Islam, and also the liberalism that has been discredited by ongoing imperialisms and occupations, whether in Palestine or Iraq. I feel that there’s a position of refusal that allows for a kind of independence so as to be able to narrate one’s story, or be true to one’s story, as you said.

There was a generation completely different from my own, who didn’t have a language in which to express themselves . . . [and who] suddenly occupied this huge space of freedom.

AA

OK, so there are lots of questions there, and this will bring us to another point we can talk about. I think understanding the role of generations is necessary, but it’s not sufficient. It’s linked to something deeper, something that goes beyond Bidayyat and other organizations and even beyond generations, and it’s related to the moment we were living. It was a moment that posed more questions than gave clear answers or formulated a coherent ideology. But there was a critical spirit, or a critical comparison between political discourses, or rather a questioning of what it meant to attempt to change society, and a questioning of what cinema meant. Inevitably, there were lots of critical comparisons and questions, such as the question of living through a moment of terrifying violence in the presence of an orgy of images, and the various uses those images taken from YouTube were being put to. This wasn’t so much a turning point as the basis of what was happening. And if you don’t have a critical stance toward it, that means there’s a problem. Because we were attempting to build a critical discourse against the various regimes—the Assad regime, the Islamist regimes, etc.—as well as against patriarchal society, in the sense of the older generations who are still in power, the dinosaurs, the founders of the National Film Organization, as well as global satellite news organizations, production companies, who came and wanted to steal images or put them to their own uses, all in the name of liberalism, free speech, and public interest.

We were training young men and women, positioning ourselves outside of this market logic, and trying to raise critical questions and approaches precisely on the question of the right to the image and violent images. All the questions and comparisons in the articles published by Bidayyat and in the work these young people were producing, or even in their satire, were fundamentally a way to deconstruct the ideological discourses and the absolutes that were circulating. That was the margin we had to play with. There were often young activists who would come to us with extreme and difficult images, and at Bidayyat they could learn how to deal with the ugliness of these images: how to discuss it without simply displaying or reproducing it. It was always very easy simply to show these images, but we tried to find a way to deal with them and discuss them through a cinematic and humanistic filter so as to build something that could connect with others while maintaining a critical approach.

Trailer for DOUMA UNDERGROUND (Tim al-Siofi, 2019). Courtesy of Bidayyat.

ST

On Monday you described yourself as a passeur—perhaps you’re a smuggler between generations?

AA

Yes, but I didn’t mean a passeur in that sense. Not passeur as in “smuggler”; more like a courier, in the sense that through my presence here in Beirut, and by founding Bidayyat, as well as through my relationship with an older generation during the 2000 Damascus Spring, I became a link in a chain of generations.

ST

I really liked the idea of a smuggler between generations. But I think this idea of being a link in a chain of generations also contains something fundamental about the concept. Generations are not just a question of difference: the idea is not just that one generation succeeds and is different from another, or that a generation becomes a positivistic way of measuring social difference through a natural feature like a lifespan or the cycle of birth, maturity, aging, death. Part of what interests me is that generations overlap; like a link in a chain, successive generations can both be different and overlay one another. Rather than a clash or a confrontation, that means different generations can be oriented to the same political events or struggles, but in different ways.

There’s a point in your interview with Hassan Abbas where you talk about your role during the Damascus Spring in the 2000s, crossing between Beirut and Damascus to get people to sign the “Statement of the 99” by hand. You were a smuggler between generations, or maybe less dramatically, a courier. In any case, you were playing a mediating role. Ten years later, at the beginning of the Arab Spring, your role shifted, and so did your perspective toward a younger generation. You moved away from an older generation of dissidents and intellectuals and toward a younger generation of activists—

AA

I admit that my friend Hassan Abbas tried to lure me into talking about my personal role in drafting and collecting signatures on the “Statement of the 99” in 2000—and by the way, Hassan himself was one of the signatories of the statement and one of those who collected some signatures. Unfortunately, the interview is no longer available online. But I remember that I tried to confirm my position, which marked the beginning of the Damascus Spring. In summary, the statement was signed by ninety-nine men and women from across several generations, including those working in various cultural fields and in public affairs, who all called for democratic reforms, the release of political prisoners, and the abolition of the state of emergency. It was a call for Syrian society, inspired in part by Eastern European dissidents such as Václav Havel, to break the barrier of silence and fear. The importance of this exceptional statement wasn’t only the way it challenged the regime and its rhetoric, but the fact that it was a collective, political stance by intellectuals in the field of politics, which allowed them to mobilize their symbolic capital without the ambition or desire to become professional politicians. At that time, in the Mulhaq al-Nahar, I published an article on the importance of the “collective intellectual,” a figure who was born in Syria with this statement.

The term collective intellectual comes from the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, and it’s closely related to the social struggles that French intellectuals waged in the mid-90s in France. But the “Statement of the 99” was a vivid example of how a group of workers in the cultural field could coalesce around a collective political position that was clear and frank in the face of a regime, without there being hierarchical political structures underpinning it, and without it being built on personal political ambition. The statement was born without an official spokesperson and without any party, organization, or institution claiming to be behind it. In this sense, it foreshadowed the nonhierarchical protest movements that began a decade later in 2011, which marginalized the patriarchal figure of the all-knowing intellectual sitting in his ivory tower.

To return to the subject of generations: I personally didn’t study cinema, but I did have some cultural and political experience. At a certain point, I made a film, Ibn al-Am, out of necessity and with very modest means. It was one of the first films made in Syria shot on a small digital camera, which embraced the aesthetics of low-res, scratched images, and which went on the festival circuit—

ST

—a film that resembled a younger generation’s films more than an older generation’s, such as Ammar al-Beik, Joude Gorani, and—

AA

They hadn’t started making their films yet. But Joude and Meyar al-Roumi studied cinema at FEMIS. That all happened three or four years later anyway. I’m not trying to say I’m the precursor, but in Ibn al-Am, the film opens with a question from Riad al-Turk, who asks me what I know about filmmaking. I say, “Nothing, really.” But by the time the film ends, I do call myself the director in the credits. When I made the film about Nasr Hamid Abu Zaid in 2010, it was the same story.

I’m trying to say that I’m sensitive to how difficult it is to make a film, not just materially or in terms of equipment, but also in terms of what it means to work with a small camera, a small team, and a small budget, and how difficult it is to adopt the label of director without any official training in filmmaking. Afterward, in Ibn al-Am, which was about a well-known leftist intellectual dissident, a communist figurehead, with whom I was also talking as a spiritual father, asking him questions about his relationship as a father to his children when I’m also the son of a political prisoner—in the end, I was asking myself all of these subjective or self-referential questions while working with a public figure, while also trying to cause a disturbance within the spaces of relative freedom available at the time. The same goes for the film on Nasr Hamid Abu Zaid. I was working on an important public figure but from my own personal perspective.

There’s no doubt that when the revolution started, and we tried to distribute those small cameras with Kayani, and they captured such big stories, that I had a real bias for the young women and men who were trying to tell their stories from a personal perspective, in a way that resembled them more than it resembled the cinema of some old, well-established Syrian directors, who were giving cinema lessons to young people while they were dying and while their hands were trembling.

Excerpt from WAITING FOR ABU ZAID (Mohammad Ali Atassi, 2010). Courtesy of the filmmaker.

ST

I also remember observing a workshop in Istanbul in the summer of 2018. We were watching rushes together, and activists who had recently crossed the border from Azaz and Idlib, and who had recently survived sieges and cease-fires in places like Yarmouk, Ghouta, and Daraya, would play clips that sometimes involved images of corpses, of their fallen comrades, or of mass graves. This wasn’t perpetrator footage. They would play the clip and you would say, “No, no, no! I can’t watch! The right to the image!” and you would physically turn away. But for these young people, this was the reality of what they were living. So, for them, the idea of screening it back in a room wasn’t even a question, let alone an ethical dilemma. My question is about this contradiction: The politics of the right to the image is, on the one hand, very embedded in the issues thrown up by the struggle in Syria. It’s part of a refusal of the market, of spectacle, and of the regime’s and radical Islam’s image politics. But on the other hand, it does represent a rupture with the everyday practices of image-making and circulating that young people engage in, which I could see for myself in the footage being shot by activists, even by those who were committed to a more creative treatment of actuality than typical propaganda footage.

AA

I don’t remember if I ever actually said, “Right to the image!” I find that surprising. I could have said, “I do not want to see these atrocities depicted in this offensive manner.” I’m unwilling to see images that first violate the rights of people depicted, and second violate my own humanity and my right to protect my psychological well-being from an abusive spectacle.

In the case of Bidayyat, in my opinion, the issue isn’t only related to the question of the right to the image. It was about a relationship of the person filming to their own material, and an ownership of that material, and an ownership of their own story. In the end, they had more right than anyone else to tell those stories in the way they wanted to tell them. I didn’t want to impose anything on them beyond the most basic ethics: don’t lie, don’t make us suffer the trauma of seeing these images without our consent, and don’t violate the sanctity of the body. The rest is their story, told in the way they want to tell it. We only posed the questions necessary to be able to achieve that, so that they were able to make a film, with credits, subtitles; a film that a festival might pick up, where it might win a prize. Most important is to create the conditions so that a cinematic work of art can be born that has an independent life of its own. The issue isn’t only the right to the image; it’s about what it takes to become a director of an auteur film. They’re telling their stories, not just in images and narratives, but also in the film’s rhythm and narrative structure, which all go into making it a film—not propaganda, or hate speech, or racism, or sectarianism, or any kind of harm more generally. It’s a package: how to be authentic to oneself, and to make something true, deep, innovative, and complete.

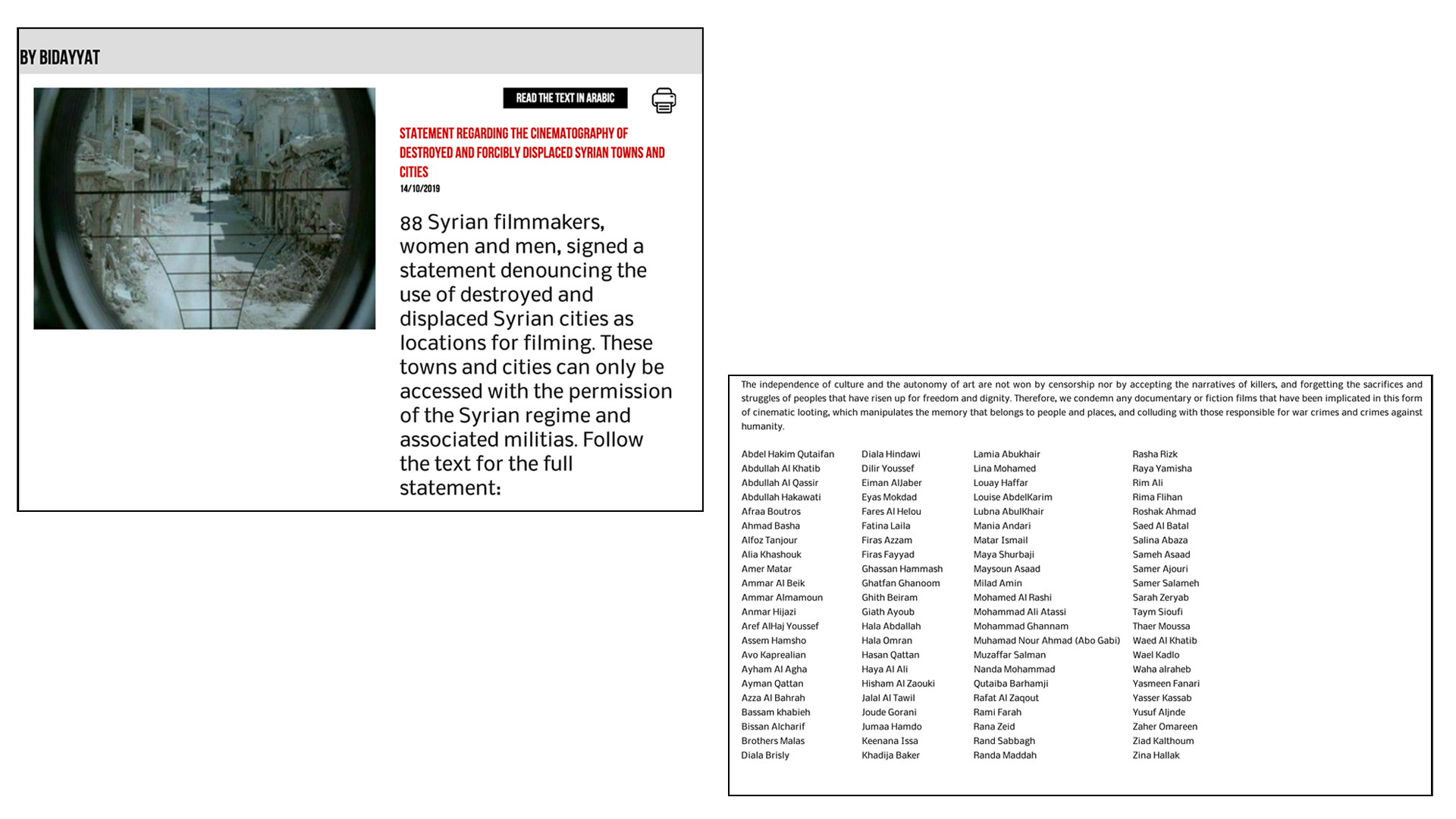

But if someone wants to show corpses and use Bidayyat’s logo, go make the film somewhere else. That’s our line, our ethical position. For everything else, they’re totally free. There’s something else that began to happen later, and that links to filming in certain areas with the support of the regime. These destroyed areas had become crime scenes. We believe that they must be respected as such and as lieux de mémoire, while in fact they were being repurposed as backdrops and film sets, as in the case of the Ahmad Ghossein film.

ST

Yes, Bidayyat published a series of articles in 2019–20 by Samir Frangieh, Rana Issa, Khalid Saghieh, and Bilal Khbeiz, which I translated from Arabic to English for the Bidayyat website, on the case of Ahmad Ghossein, who had used the destroyed town of Zabadani as the backdrop for a film set during the July 2006 war by Israel on Lebanon.{4} What was controversial, perverse even, in the case was that he had been granted access to Zabadani by Hezbollah to film there, when Hezbollah had gone from acting as defenders of Lebanon against Israel to perpetrators, fighting with the Assad regime to quash the revolution in Syria. When the way Ahmad Ghossein produced his film became public, it led to a 2019 statement organized through Bidayyat, condemning the practice of tafyish—the widespread practice by regime militias of furnishing one’s home with looted goods seized from the houses of the displaced—in filmmaking, in this case using “crime scenes” as “film sets.” It was also a sign of the shifting role that Syria was playing in global and regional filmmaking. In the middle of the revolution, in 2014, Syria suddenly became one of the capitals of documentary globally, especially after the rise of ISIS. And with the turn of global attention toward Syria, especially during the second half of the Syrian revolution, the humble means in terms of equipment and budget that you described in the 2000s and at the start of the revolution became less familiar. Suddenly there were big budgets and high-tech cameras operated by big production crews. So that question that you asked in the beginning about the importance of documentary filmmaking in Syria as well as the importance of Bidayyat, whether Syria is part of a larger technological revolution that’s happening related to digital media or even whether Syria was pioneering those changes—I wonder whether it’s a tale of two halves. There are the humble beginnings of the revolution, and then there’s the point of professionalization, stemming from both the rise of the Islamists and the domination of a global market that you’re describing.

AA

That’s obvious. I don’t want to name names, but if you watch Last Men in Aleppo (2017), Of Fathers and Sons (2017), The White Helmets (2016), War Story (2014), or The Cave (2019), suddenly you have these big companies with budgets of over a million dollars, as well as TV stations imposing decisions that probably aren’t being made by the director. It was like the conceptual art being made in Beirut—after a certain point it was being produced for a foreign market, rather than for exhibition locally. Bidayyat, especially when we moved into coproduction later on with a French producer—in particular with Still Recording (2018), but also with Our Little Palestine (2021)—my one condition was that we remained majority owners. The French coproducer could take a bigger cut of the profits, I didn’t really care. But I wanted us to remain majority owners on paper so that we, by which I mean the young director and Bidayyat, maintained control of the final decision, the final cut, and the distribution strategy. These kinds of decisions aren’t just a means of protecting a young director; they’re about us having the final say, not just “us” in the sense of Bidayyat, but in the sense of the owners of these stories: us Syrians. It’s so that someone from abroad with capital can’t come and buy up everything and make the final decision.

ST

Is this what the right to the image means to you? Because in your article in Al-Jumhuriya, you write that the right to the image means having an ownership, a kind of copyright, over the images you produce or that are produced about you.

AA

No, this isn’t related to the right to the image. In the end, I have an experience that I lived, and that my whole generation of filmmakers lived, which was trying to make films with small budgets, or with no budget whatsoever, and with all the constraints related to the technology and equipment available at the time. This younger generation had the same problem at first. But then the scale of aid and funding exploded until we reached the point we’re at today with these massive coproductions. Bidayyat’s priority has shifted to helping us maintain our independence, while prioritizing training over product. If you look at all the young men and women who worked with Bidayyat, almost none of them studied cinema. They learned cinema on the ground, with Bidayyat, and in workshops. That’s one fundamental point. The other fundamental point is that it’s true there are young filmmakers we worked with who don’t give Bidayyat any credit, and I have no problem with that.

ST

There are two challenges that frequently get leveled at Bidayyat and the young directors you’ve supported over the years. First, that the young people you work with aren’t really directors, that you can only really call yourself a director once you make your second film. The first film doesn’t really count because it’s wholly dependent on an exceptional historical moment, which meant that the young person managed, in spite of their lack of skill, to film exceptional material. Bidayyat then brought in high-quality editors to turn that exceptional material into a documentary. The second challenge is: If Bidayyat is successful because it gives someone like Abdallah al-Khatib or Saeed al-Batal the opportunity to call themselves a director, then there are also counterexamples, such as Ziad Homsi. He’s someone you asked to film, who filmed for you in Our Terrible Country, and on whom you imposed the label of director. It ended with deep disagreement, with him disavowing the film, very publicly, and asking you to withdraw it from circulation, and even with him breaking down.

AA

The first question about amazing material, incredible stories, and a historical moment—I think that’s already been answered in practice by the filmmakers. Of course, these are incredible stories, traumas, a pressure cooker that exploded, which also exploded creativities. When creativities explode, I don’t think people stop after a first film. Some give up, others continue. There’s also the counterexample: the people who don’t have material, who don’t have an incredible story, and who didn’t live the historical moment directly, and yet they made an incredible film. Like the film that deals directly with the issue of not having firsthand images, On the Edge of Life (2017), by Yaser Kassab. It’s about being in Sweden and filming exile. There are also lots of examples of young directors who continued, and in very different circumstances.

I think Bidayyat took great strides on the question of who a director can be, and what it means to be a director. When we write “Directed by Abdallah al-Khatib” in the credits, just like I once put “Directed by Mohammad Ali al-Atassi” in the credits, that title of director wasn’t bestowed by an institution or a diploma. It was earned through making a film. Once they’ve made a film, no one should dispute their right to call themselves a director. Afterward, one can call them a bad director or a good director if one wishes. But if the young person considers the work to be a film, then that is the case. Many others would say that this isn’t a film, and you’re not a director; even if you went to the Berlinale, you’re still not a director, and that isn’t a film. But I maintain: the final decision belongs to the young person, whether they choose the title of director, and choose to call the work a film or not.{5}

ST

To the subsequent question about Ziad Homsi and the violence of imposing the category of director. You have described becoming a director as an achievement, almost as a gift, or perhaps not a gift but certainly an elevated status. But it can also entail its own violence.

AA

On the question of Ziad, I think he was subjected to a psychological and physical ordeal during his arrest by ISIS and Nusra that was extremely difficult, almost unbearable. But I don’t think that’s a justification, or that’s not the reason for what happened. When Samira al-Khalil and Razan Zeitouneh were kidnapped, I was still working for a month on the editing [of Our Terrible Country]. A month later, I released the film. At first, I didn’t want to list either my own name or Ziad’s. I was going to credit the film simply to Bidayyat.

ST

Like Abounaddara?

AA

Like Abounaddara but not because of them, since we’re not a collective. But I had a conflict of interest. First, I knew I had to make the film because of Razan and Samira’s story, but I didn’t want people thinking that I was just using Bidayyat to fund my own projects. Second, Ziad wasn’t there during the editing process, and he had also become a character in the film. I remember some of our mutual friends telling me that it was clear I was filming Ziad, and directing him, and that Yassin al-Haj Saleh was my friend. They were right: I filmed the second half of the footage, from Raqqa onward to Istanbul. But the first part of the film, in Douma and on the journey to Raqqa, was shot by Ziad in my absence. The material shot by Ziad bears his fingerprint, not only as a photographer but as a director, meaning that he made decisions alone, in isolation from me because I wasn’t and couldn’t be present: questions of when to film and when not to film; questions of framing, sound, etc.

Excerpt from OUR TERRIBLE COUNTRY (Mohammad Ali Atassi, Ziad Homsi, 2014). Courtesy of Bidayyat.

What is certain is that the second part in Raqqa and in Turkey was under my full supervision as a director, and it bears entirely my personal imprint. Although it’s true that the basic directorial decisions were made at the editing table in the absence of Ziad, who agreed to them later in Istanbul when the final cut was shown to him and Yassin, I’m also certain that Ziad was a partner in directing the film. It was ethically and professionally impossible not to list his name as codirector. Today, I’m proud of the film. I’m happy that it came out. It’s a document of how Yassin al-Haj Saleh managed to get out of Douma and everything that happened subsequently.

ST

Even in 2014, you named the film Our Terrible Country, so—

AA

I didn’t invent the title Our Terrible Country. Yassin used the phrase. There were people complaining that I never filmed Yassin thinking or writing. I did something very strange in the film. I never spoke to him as an intellectual or a thinker. But I did give him the space in the film to read a text that he wrote upon leaving Syria and entering exile. We left it in the film as a voiceover. I didn’t use my own voiceover, and he didn’t write that text for the film; it’s the text written for his own exile in formal Arabic, not in spoken Arabic. And that’s the space we gave him as a writer. That’s why we called the film Our Terrible Country.

[I don’t know exactly what I’ll do in exile.

I have long felt uneasy about this word.

It seemed like mockery coming from those who remained in the country.

Today its meaning might change to include our overwhelming experience,

the experience of uprooting, escape, and dispersal,

and the hope of return.

I don’t know what I’ll do, but I am part of this great Syrian exodus,

and of this Syrian hope of return.

Even though it resembles a slaughterhouse today,

this is our country; we have no other.

And I know that no country will be kinder to us than this terrible country.]

—Yassin al-Haj Saleh in Our Terrible Country

ST

One of the things we haven’t really discussed yet is the publishing work that Bidayyat has done through its website, Bidayyat.org. Also, the risks that Bidayyat takes with publishing young writers. The first text I ever wrote about Syria was published by Bidayyat when no one else was interested. So, I’m biased, but I think Bidayyat deserves recognition as a platform for publishing young writers. It has always taken pride in the local context, in the sense that from the position of a local context, you have a right to talk back on every level: from intellectual debate among Syrians on the politics of image production and circulation, to the relationship between global capital and local production. Who did you imagine as the audience of these articles?

AA

SyriaUntold published a dossier on the subject of cinema and audiences.{6} First of all, I think they took the wrong approach. There was a real inferiority complex. Why are the questions that get asked about Bidayyat’s and other similar organizations’ audiences not also put to other experimental, artistic, and avant-garde attempts at filmmaking elsewhere? When you have a national cinema, a national TV industry, a national festival circuit, and you’re present inside the country, then you can pose their questions with their logic: What’s the scale and scope of Bidayyat’s national audience?

Conversely, if an audience is small, it doesn’t necessarily mean a film isn’t important. A TV series isn’t important because 30,000 or 300,000 or 3 million people watch it. If only 3,000 people ever watch an experimental film, that doesn’t mean the film is necessarily less important. It can even have different kinds of impact. It might become a historical document, for example. The second point, and this is central when evaluating films on the basis of the size of an audience: there aren’t clear criteria in the sense that some of the SyriaUntold articles discuss.

ST

There’s also the fact that half of Syria has been displaced, with a million Syrians in Germany alone. It’s possible that Syria’s national audience now exists, at least in part, in exile and diaspora. The life of a film as a historical document can also be unpredictable. Your film Ibn al-Am is a good example: When it was first released, it wasn’t screened widely, and it was distributed by hand on DVDs. Then, when the revolution started, you uploaded it on YouTube and it received a much larger audience. Finally, Mohamed Soueid programmed it for Al Arabiya to mark the first anniversary of the Syrian revolution in March 2012. Eventually, thousands, potentially hundreds of thousands, did watch the film. You could say that the temporality of an experimental documentary of the sort you’re making in Bidayyat is different from the temporality of a film made for TV. And the relationship to history is different too. Do you think of Bidayyat films as time capsules, objects made for the future, for future generations to find?

AA

Exactly. Take the film Our Little Palestine. We got a grant from Al Jazeera Documentary. It was an open call, and we won the grant, which stipulated that the whole film, from start to finish, should be screened on Al Jazeera. Our one condition was that they couldn’t screen it immediately, that they had to wait a year so that it could go on the festival circuit. In a year’s time it will screen on Al Jazeera Documentary.

The point is that the idea of an audience is relative. The problem begins when you only produce films in order to serve one particular audience, then that audience begins to impose itself on you. One essential part of Bidayyat’s work in training and production is to make sure our films reach audiences; audience is not a useless concept for us. We want our films to be successful, we want them to go to festivals, perhaps to go on TV, and eventually to go online. In fact, at first, we wanted to put all our films online, then we discovered that once they’re uploaded online, they lose the right to go to most festivals. Part of training a young filmmaker so that they know what it means to be a director involves going to festivals. And when they do go to festivals and start winning prizes, it’s an amazing feeling.

ST

They also start to feel like directors; they become more receptive to the category.

AA

But what’s funny, or ironic, is that some articles in the SyriaUntold dossier reproach Bidayyat for sending films to festivals, which they call “international festivals.” But these films weren’t going to Cannes or the Oscars; they weren’t on the red carpet. They were often at smaller, alternative festivals.

ST

There is a global critique, especially prevalent in Europe and North America, of international and experimental festivals exerting hegemony on the production of independent and experimental documentary cinema. It’s not a local critique of Syrian cinema per se.

AA

The idea is that there are lots of Bidayyat films that go to festivals, and some that don’t make it. We’ve never been guaranteed a slot at any festival. Sometimes festivals would take one Bidayyat film then reject the next. It depends on the selection committee, the quality of the film, and all the other factors. But I feel that lots of opportunities arise for films that go to festivals—it grants them visibility, it opens access, it’s a great experience for a young filmmaker. The scandal, in my opinion, is when people come—like you, Stefan, or others [said jokingly]—who reproach us for making films just for the European or American market. That’s simply not true. But it’s normal that, as with all directors the world over, when our films are released they go on the festival circuit first, before being screened on television or going into general release in cinemas. Still Recording did go into release in France and Italy. Now Little Palestine will go into release in France, and then screen on satellite TV afterward. Tant mieux! Why not?

Poster accompanying the French theatrical release of STILL RECORDING (Saeed al-Batal, Ghiath Ayoub, 2018).

Poster accompanying the French theatrical release of STILL RECORDING (Saeed al-Batal, Ghiath Ayoub, 2018).

ST

OK, I’m not against that. But there was circulation within Syria too, which the critique sometimes neglects. People like Saeed al-Batal, Abdallah al-Khatib, and others made a huge effort to make it possible for different communities in liberated areas to watch their films inside Syria. And also to screen other films that weren’t their own inside Syria. Even if this aspect wasn’t particularly well documented, that circulation was also taking place on a low-key basis alongside the festival circuit.

AA

Abdallah [al-Khatib] wants to screen Our Little Palestine in Azzaz [a town outside of regime control in northwest Syria]. And we took the risk to screen Still Recording in Douma, even if or especially because Zahran Alloush and Jaysh al-Islam opposed it.

ST

Did you screen Our Terrible Country in Douma?

AA

Yes. Saeed al-Batal organized the screening when he was still inside the country.

ST

What is your relation to the revolution today? Has it become an event or a period of time consigned to the past, or does it still constitute some of your horizon for the future?

AA

It’s a very philosophical question, and I’ll try to interpret it in my own way. Today, we’ve lost a country, the country called Syria. I don’t know when we will return, or whether we’ll ever be able to return. But I don’t think we should lose our narratives, our stories. Our stories are not just the archive that will remain outside Syria, or our memory, but what we can do with that archive and our skills, whether or not we succeeded in becoming filmmakers or writers.

The question is about what can be done. I think that’s very important, because the young women and men who today are in Berlin, Paris, or Amsterdam, or even Istanbul and Beirut, their Syrian past has gone up in smoke, but it’s also still there in the material. And there’s another generation who left Syria aged eleven, who grew up outside Syria, and who don’t have direct access to the story of Syria. What’s important today is to attempt to keep alive this narrative on their behalf, whether they grew up abroad afterward in Europe or Lebanon, or even those internally displaced in Syria.

What is that story? It’s that, for a while, there was a generation of people in the region who demanded dignity, freedom, and who took to the streets, and who were able to bring down regimes, and that those people were met with terrible violence. That’s the headline story. And within it there are lots of stories, a wealth of stories, related to all the details of ordinary lives lived.

Unfortunately, Bidayyat is in a difficult position in Lebanon, because the relation between and circulation across Syria and Lebanon has gotten much harder. The majority of people who came with a background in theater, art, or cinema have now emigrated abroad. It’s a huge loss for Lebanon and for Syrians in Lebanon. Bidayyat’s raison d’être no longer exists in Lebanon. As a structure, we will remain; we’re not shutting down, but we’re stopping. It’s possible that a young person might take up the structure and use it in the future.

Personally, I feel that after ten years of being filled with dreams and defeats, at this moment it’s important for me to return to myself, to my own personal work, to my own films and writing, and to try to find myself once again. I’m asking myself difficult and fundamental questions. I’m very frightened that I’ll have to live another exile, this time from Lebanon; that I’ll lose this country I’ve lived in for over twenty years. This is a real question that haunts me. I’m also reexamining my own tools and techniques: I can’t go back to making films with shaky images and scratchy sound. I have a different set of questions, and I’m thinking through them and trying to find answers.

ST

What are the kinds of questions you’re asking—can you give an example?

AA

I’ve already answered you. Look, in this region, we’ve experienced extreme, even scandalous losses as Syrians, Lebanese, Palestinians. Mine are questions linked to our place in the world: the relation of the world to us, and ourselves to the world. And then there’s something very personal: the work on the self, on memory, on trauma, on creativity, on skill. For example, when I look at my old films, I’m always disappointed; I don’t like them, I should have gone further, I want to go a bit further. That goes down to technical details: should I have used a voiceover, how should I use my material, what’s my relationship to my images and my archive. Then there’s the question of the relationship between the “West” and our region, the questions of Islamophobia, racism, and Eurocentrism. All of these issues are alive for me. I’m not living the same kind of exile as a Syrian living in Berlin; I’m not living a life of partying and hedonism and Berghain. I’m still in the region, close to Syria, and I don’t want to leave. But I might be forced to leave.

ST

From the start of the interview, I’ve been trying to speak to you on a personal level. And you kept returning to the question of structures and contexts—sociological issues. But now, as we reach the end of the interview, you’re returning to personal questions. Can you reflect on that: Why is it OK to speak about the personal now when we couldn’t before?

AA

I’m not speaking on a personal level in the sense of me personally; I’m talking about the personal in relation to Bidayyat’s work. Once again, I return to Guy Debord: Les hommes ressemblent plus à leur temps qu’à leurs pères. It’s just the idea that the context, or the historical moment, is fundamental to understand a person; no one is unique. Everyone is part of a social structure, an environment, a conjuncture. And even the personal is a part of that. I don’t have other answers.

In the space of less than ten years, half the population of Syria has been displaced, half the country is living in exile. And the Lebanese, previously with the civil war and today with the economic collapse, are migrating abroad en masse. The same goes for the Palestinians, who have been forced into camps and zones. And look what happened to the Iraqis.

Our region doesn’t just lack political “stability,” to use that ugly technocratic jargon; our region is the result of conditions and costs imposed on us. At the end of the Second World War in Europe, anyone could take out a loan and go to university, or send their children to university. In our region, we can’t think two years ahead, even a year ahead. The great tragedy of our lives is that they can be transformed from one moment to another, that suddenly we won’t be able to find milk for our children, or that we’ll find our homes destroyed—look at what happened to Aleppo, or Homs! From one day to the next you might find yourself a refugee.

The very idea of stability—the ability to think ahead, to plan—no longer exists. People find themselves from one day to the next in a country that’s been transformed. In 2006, Israel attacked Lebanon. The boats came and evacuated the foreigners. You don’t own your decisions; your decisions are owned by people with no regard for your humanity, who consider you to be an ant. At the same time, one might have the desire to live in this region, to produce films here. But the cost is living in a region where the most basic decision of whether you can stay or must leave—you don’t even own that decision.

There are privileged people like us who have foreign passports and who can travel, but the majority can’t. And even those like us who can travel, we don’t fully own the decision whether or not to stay.

So, the ability to think about the future is extremely difficult. You can’t make these decisions. The fundamental thing, I think, is not to be a mere object [مفعول به]. It’s not just the decision whether or not to leave, but the ability to write, to make films, to bear witness, to testify, to feel like you’re not simply an object, something acted upon, but rather something that acts. There’s a terrible collective trauma that people in the region are living. And on an individual level, there are massive shocks that we aren’t yet able to comprehend.

The very idea of stability—the ability to think ahead, to plan—no longer exists. People find themselves from one day to the next in a country that’s been transformed.

ST

I tried to write about this shift in terms of what question we ask ourselves. I feel like for ten years or so, we’ve been asking ourselves how we can get our rulers and regimes out, how we can force them to leave like Ben Ali left Tunisia. Yallah irhal ya Bashar! But now we’re asking ourselves another question: we’re asking ourselves whether we should leave or not. And this is a huge loss. This shift from one question to another captures something of the defeat.

AA

Of course there’s a huge loss; there’s been a counterrevolution, and there’s defeat. But like I told you, it’s not just the tragedy of defeat, a destroyed country, and exile; there’s also a danger that a generation grows up thinking that Bashar did the right thing, or that he didn’t use chemical weapons and didn’t kill people, and that it was all about armed gangs. There are still those basic facts that need to be struggled for. To be able to achieve that, we need to preserve our story. And the more our narrative is open to others, the truer it will be; the more closed our narrative is, the narrower it is, the more partial it becomes, the less likely it will be to survive. That’s why I love a particular scene in Still Recording when someone from the regime and a fighter for the opposition are communicating via walkie-talkie. It’s a rare scene in recent documentaries—it shows something really true, very real. Or take Saeed’s presence in Douma as an Alawite, which undermines the regime’s narrative as well as the opposition narrative that there were no Alawites with the revolution, or that they supported the revolution from the comfort of their five-star hotels.

ST

In the end, we’re left struggling for these basic facts, for details that, no matter how small, can complicate matters and discourses.

AA

Yes, or another example: Our Little Palestine undermines all that leftist discourse about Bashar al-Assad being a bastion of support for Palestine. When you watch the film, you realize not only that Bashar trades on the Palestinian cause, but that he’s inflicted massive harm on Palestinians in Syria. Today, the discourse from some Palestinian leftist groups is that the only problem was ISIS. That isn’t the fundamental position of the film. The film is about Abdallah telling his story and his version of the story of the camp, telling the story the way he wants to tell it. But there is this political side of things that’s present, which anyone can interpret as they want.

ST

Thank you!

AA

I feel like a car running out of gas.

ST

Like you say, everything has its own rhythm—

AA

Hold on, hold on, don’t stop recording. I think there’s one more fundamental question related to why documentary cinema played this role. And documentary cinema in Syria isn’t unified. There are big productions, and there are more artisanal—I think more real—films. Take the film For Sama (2019), which is quite problematic, although I like the film. It’s Waad Al-Kateab’s personal story, and the story is real, and it’s a story she was living and capturing not in order to make a film. She was simply documenting, and then Channel 4 came along and took the film somewhere else. There is something real and authentic about the film, something that follows a certain ethos. But at the same time, if that film had been made by Bidayyat, it would have been impossible to leave those bloody scenes in the film . . . impossible. Because I think they’re wrong. They are flaws in the film.

ST

I don’t agree. There’s a scene of a mother removing her baby’s body from the morgue, refusing to let the hospital keep the body, and insisting on burying her own baby’s corpse. I cried for an hour after watching that scene. It seemed to capture a moment I didn’t think possible outside the mythological world of Greek tragedy.

AA

But do you think that woman was asked whether she wanted Waad to put her dead baby in the film and follow her with her baby’s corpse in her arms?

ST

But that’s just what Waad Al-Kateab did in the moment. There was no one there telling her to follow the woman. And she didn’t sell her footage; it was a personal decision made within a context and in the thick of a moment. It’s not reducible to the market speaking through Waad Al-Kateab, and I bet no one forced her to put that scene in the film. This wasn’t supposedly “leaked” footage that was actually circulated intentionally by the regime, and which a filmmaker was rather foolishly recirculating. But if she had come to Bidayyat, you would have forced her to remove the scene.

AA

I wouldn’t have forced her, because I can’t force her, but I don’t show dead bodies with faces covered. No corpses. Perhaps we could have convinced her to keep the scene but to edit it differently. I’m sure you would have felt the same way about it, but without violating the rights of the mother holding the body of her son in her arms. I spent half the film shielding my eyes; I couldn’t, I can’t. I don’t know what would happen to that mother if she saw the film.

ST

The difference, I think, is that I’m not against corpses, violence, or a violent image in itself. But I’m with you that we have to find a way to represent violence and death without reproducing violence. I don’t think the right to the image should be a law or regulation against violence and violent images tout court. If anything, I think it should be a kind of training in an ethos, to work with violence and violent images in a way that respects dignity, which is mostly what Bidayyat did: it trained young filmmakers in an ethos, in the virtue of dignity rather than the law. Therefore, we have to find that way of doing, that ethos for dealing with corpses and violence with dignity; and that way of dealing with them can’t always be to cut. Handling images with dignity is the central problematic, not deciding what we should forbid. For example, I do think it’s possible to do a close-up of a corpse with dignity; Abounaddara does so in their feature film, On Revolution (2017). It’s not a question of distance, or veiling, or shrouding the body, or even of creating an allegory. One question might be whether or not your relationship to images began with words, when you began taking testimonies from former prisoners of conscience. In your interview with Hassan Abbas, you mentioned an event in Tadmor prison that you refused to represent. What was it?

AA

Stefan, I also don’t call for laws or regulation to prevent people from displaying violent images in public. But there are professional ethics that must be respected, and the individuals in the images have rights, and the people watching the images also have rights that must be taken into consideration. From here it is important, in my opinion, that we, those involved in the field of cinema, create a common visual culture that makes it difficult to continue committing the violations being depicted.

Do you know what my first relation was to images of atrocity? Osama, a greengrocer from the Hauran, gave me a USB stick on a quick stop-off in Beirut before returning to Deraa province. I spent about an hour and a half watching the clips. They’d never been released or circulated, so I wanted to watch them all. When I finished, I don’t know if I even managed to watch them all, but I sat and I cried. I fell apart. I felt like something inside me was suffocating. Physically, these kinds of images are unbearable. They go beyond my human capacity to watch. There was something inside me that—

ST

I think this is a very important point with regard to the discourse around the right to the image. First of all, this discourse is against a specific set of regime practices and politics: of repression and terrorization. But on the other hand, staring at atrocity allows the viewer to know the reality of the Assad regime and the repression that people are living. It brings it out in the open when for decades it was hidden—in prisons, police stations, military barracks. This is one of the dilemmas of the Syrian revolution attempting to bring down this regime and its state, l’État de barbarie, to use Michel Seurat’s term for it. You have two options: you can watch and somehow become more aware, or you can reject this politics and say, no, watching doesn’t help, it participates in the regime’s brutality.

AA

The method of presenting the idea here is wrong, because you assume that the defenders of the right to the image simply want to turn away from atrocity, and you generalize viewership to “the people.” In fact, the opposite is true. We have to continually ask ourselves how we see what we see, how we represent it, and how we transmit it in images, without it becoming banal and without it violating the rights and humanity of others. Once again, do I have to watch unedited videos of the rape of a woman or a child—even if they are included in a cinematic work, as they have been in Syrian documentaries since 2011—to realize the enormity of the crime of rape? Of course not.

On the other hand, we haven’t stopped watching for ten years, and nothing has happened. They took all the Caesar Files and they turned the photos into an exhibition. You end up hurting more people, and it reveals the banality of violence. It’s a misinterpretation, a misunderstanding to think that we gained awareness through these images. The right to the image is not about hiding or not looking, or not taking into consideration these photos about crime and violence and violation. We definitely need to preserve these images, and we definitely need to establish institutional settings for viewing them. But the idea that we have to stare at them, turn them into exhibition objects . . . If ISIS cuts off someone’s head, do I have to watch how they cut off the head? Or see the head on the ground? There’s no sense to it! It kills something of your humanity. Instead, we have to take into consideration the act of violence as a result of something having happened, and convey to the world that this violence has taken place, and that this is brutality, barbarism. They’re not just corpses; they’re people with names, relatives. What rights do they have?

And to the second point, which is about double standards. In the “West,” they don’t circulate those kinds of images about themselves, but they circulate them about us. The first day after the Bataclan in Paris, Twitter banned all those photos. Show me one photo from inside the Bataclan. Yet it was a huge massacre, with two hundred people taking cover, and everyone with phones, and the killer there. But there’s not a single image circulating online from inside the Bataclan.

ST

Perhaps that’s the crucial point of the right to the image: that the people who formulate these concepts and perhaps the rules that emerge from the concepts should be the people most affected, who are positioned within the context, within society, and who know the problematics of circulation itself—people like the filmmakers who made their films with Bidayyat.

AA

It’s not a black-and-white issue. I think we should always keep room for interpretation, not shut down the debate. But also, this is a debate grounded in people’s lives, experiences, feelings, and sensitivities.

Translated by Stefan Tarnowski

Title video: Our Terrible Country (Mohammad Ali Atassi, Ziad Homsi, 2014) \ Waiting for Abu Zaid (Mohammad Ali Atassi, 2010) \ Ibn al-Am (Mohammad Ali Atassi, 2001).

{1} Mohammad Ali Atassi, “My Syria, Awake Again After 40 Years,” Opinion, New York Times, June 26, 2011.