Bidayyat \ Capturing Time, Briefly

Qutaiba Barhamji

My first question working with directors at Bidayyat was always: Why did you start shooting? For a long time, I didn’t have an answer. I was certain only that it wasn’t to make a film. But in order to make a film, I had to find an answer. This question—the why?—was the key for finding a filmic language that could understand the intention of the film we were about to make.

None of the directors I worked with at Bidayyat—whether Saeed al-Batal, Ghiath Ayoub, Tim al-Siofi, or Abdallah al-Khatib—had studied at film school, nor had they ever made a film before. They had all done a few workshops with Bidayyat, which usually consisted of a few small exercises. But none of them had ever written a script. They’d never thought about the evolution of their characters, nor how to film a space, nor how to construct a narrative arc. But what they shot was somehow stronger because they hadn’t thought about these things. The key, I think, was that they filmed with intuition. The why? came later.

During one of his classes in Paris in 2007, the film theorist Michel Chion told us, “If we could control time, we would never have made any choices.” The sentence has stuck with me ever since. What if we could control time?

Later, in 2015 in Los Angeles, an Armenian actor told me that my surname stems from the Armenian family name Barhamjian. It wasn’t uncommon for a family escaping the genocide in Turkey, he said, to change their name and religion. I knew that my family came from Turkey, but nobody in my family knew whether or not we were Armenian Christians. We were Arab Muslims, and there were no photos or documents that could prove otherwise. But of course, the goal was to erase any proof of the past, to start anew in order to survive.

As an editor I’ve always thought of myself as a time lord: someone who controls narrative, gives order to dramatic events, and lends images meaning in a world devoid of it. I’ve always been fascinated by directors, especially their sense of belief and the path they’ve taken to tell their stories, to invest them with meaning. “Pick up a camera and start shooting something with the intention of making a film,” James Cameron says, “then you are a filmmaker.”{1} But the directors I met through Bidayyat never picked up a camera with the intention of making a film. Why, then, did they do it?

I’ve never fully gotten to the bottom of the question. I edited four films for Bidayyat; on three of them I shared the editing. The first was 194. Us, Children of the Camp (2017), by Samer Salameh. I was the second editor on the film, and later there were two other editors, including Samer himself. It wasn’t the most pleasant experience. I couldn’t find the right approach to convince the director to trust me, nor could the other, more experienced editors. But it was while editing the film that I first saw some of the images Abdallah al-Khatib had shot in Yarmouk Camp during the starvation sieges (2013–15). The images haunted me until I finally met Abdallah three years later, when I began working on his own film, Little Palestine (Diary of a Siege) (2021). I remember trying to use the images in Samer Salameh’s film, but I simply couldn’t. I had so many questions, and I couldn’t find an answer to them. Once, I called [Mohammad] Ali Atassi, the founder of Bidayyat and producer of the film, and told him. Ali replied that I shouldn’t use the images if I couldn’t understand them. He said that one day Abdallah would make his own film with the images. Shortly afterward, I left Samer’s project.

Two years later, Ali contacted me for a project he referred to as “Al-Sahra” (the desert), which later became Still Recording (2018). He told me there were five hundred hours of footage, and that three years of work had already gone into the project, but that there was still a lot of work that needed to be done. “We have a rough cut of three hours,” he said. “Would you like to watch it and then we can talk?” A few days later, I was on a plane for five weeks of nonstop work on the film with the directors, Ghiath Ayoub and Saeed al-Batal.

I’d never seen images like Ayoub and al-Batal’s before. They were powerful, but I couldn’t locate any meaning behind them. Or a vision. It seemed like the powerful events in front of the camera had destroyed all intention. When I saw the footage of Abu Kinan, who was shot by a sniper and fell to the ground while filming, I was stunned. I was speechless. The camera was still recording, but there was no longer a human eye behind it.

In the previous rough cuts, the sequence was in the middle of the film, acting as a dramatic turning point in the story. Placed there, it changed the motivation of the main character, Milad. But for me, the sequence meant something more than that. I had to gain the trust of Ghiath and Saeed, who couldn’t have been more different from each other. One was calm, the other a ticking time bomb. Entering the project after a long editing process, I had the opportunity to try out ideas that the directors hadn’t been open to before. They were exhausted, and a different perspective and some new energy were useful. I had an intuition that the key to the film was this shot and that everything else should be built around it.

STILL RECORDING (Saeed al-Batal and Ghiath Ayoub, 2018).

STILL RECORDING (Saeed al-Batal and Ghiath Ayoub, 2018).

So, I began by asking questions. It’s crucial for me to get to know a director and their intentions. Sometimes intentions are buried deep, and I need to dig in order to find them. “What’s the film about?” is my daily question. My second daily question is “What are we eating today?” The second is easy to answer in Beirut; the first is difficult everywhere.

I couldn’t watch the over five hundred hours of rushes. But I was lucky because Saeed knew them very well. One of my questions was why an audience would want to watch a film shot so poorly. The camera moves in every direction; characters are never followed to build a dramaturgy; some disappear unexpectedly; Saeed, as a character in the film, is almost always behind the camera.

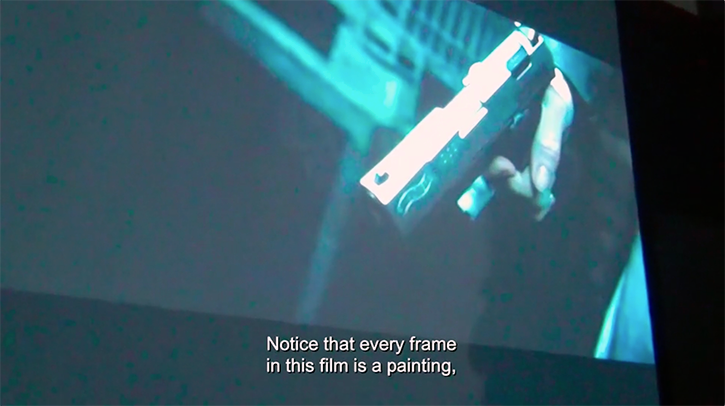

Once, Saeed told me he used to teach classes on how to film during the Syrian revolution while living in Ghouta. He showed me footage from one of these classes. He was explaining the “rule of thirds” for composing images using a film called Underworld: Awakening (2012), about human forces discovering the existence of the Vampire and Lycan clans, leading to a war to eradicate both species. During the presentation, the young people in the class were so mesmerized by the film you could tell they weren’t listening to Saeed’s explanations. And this, in fact, was the key to the film. When something’s mesmerizingly attractive, rules go out the window.

We decided to put the teaching sequence at the beginning of the film. We wanted to show the audience that, yes, we do know the rules of filming, but that during the rest of the film, we wouldn’t be respecting those rules precisely because reality is too violent, too harsh to even attempt to build a narrative or compose an image. This idea would culminate with Abu Kinan being shot by a Syrian regime sniper while his camera was recording, which again broke all the rules. But that battle I had yet to win.

STILL RECORDING codirector Saeed al-Batal uses a scene from UNDERWORLD: AWAKENING (2012) to teach cinematography during a video workshop in Ghouta, on the outskirts of Damascus, Syria.

STILL RECORDING codirector Saeed al-Batal uses a scene from UNDERWORLD: AWAKENING (2012) to teach cinematography during a video workshop in Ghouta, on the outskirts of Damascus, Syria.

Once they agreed that the main character was the camera itself, Saeed and Ghiath started finding moments in the rushes that could help us build this narrative arc. The camera, forbidden for forty years under Assad rule, had suddenly been set free. It was used as a weapon by those fighting injustice, and as a shield to protect themselves from the harshness of that reality.

At one point, Abu Kinan helps a sniper make a hole for his rifle. He points his camera through a hole in the wall to measure the angle, so as to tell the sniper how he might need to adjust the hole. The camera is used explicitly as a tool to help them kill Assad forces. To depict the camera’s role as a shield, there were images of a young journalist commenting on a massacre that we could use. But the journalist was overdoing it, and it wasn’t working. Saeed and Ghiath hadn’t used the sequence before. Watching it, I spotted a moment when he opens a fridge filled with bodies. But the fridge has broken down, and he can’t continue his act. The young journalist leaves the frame to vomit. I wanted to show this moment as an example of the camera being used as a shield, but failing to work in the way it was intended.

The crucial camera-as-shield moment was the chemical attack on western Ghouta on August 21, 2013. Saeed was there during the attack. It was a miracle he survived. The attack took place early in the morning, and for once he wasn’t holding his camera, which typically never left his hand. Saeed experienced the whole event without a shield, devoting his time to helping people throughout the night. Ghiath, who was on the other side in Damascus, saw images of the attack on television. In the rough cut, there was no mention of the chemical attack, except a scene in which one character watches the news on television. Saeed refused to show anything or talk about it. (He did, however, write an article about the event, published by Bidayyat.){2} We also had some footage from Saeed’s comrades. Ghiath and I suggested to him we try to edit something. For me, it was impossible for a film that takes place in Ghouta to skip over such a savage attack by Assad forces, an attack that killed almost 1,700 people in one night. Saeed was furious. “The audience,” he shouted, “doesn’t deserve to see it!” They hadn’t done anything when it happened, and they couldn’t do anything about it now, so they shouldn’t watch it. He stormed out of the editing suite.

We tried to put something together without him. But nothing was really working with the images. Saeed returned. Eventually, we managed to have a calmer conversation. He showed me two shots he’d filmed the day of the attack. One was a shot of the chemical missile and the people around it saying not to touch it. The second was a frame he’d taken by mistake of some dead chickens. It was only two seconds long. The two shots were the key to the sequence. We had to build something powerful but not shocking. We decided to include text, giving the date of the attack over a shot of the sunrise over the city. Then we used the two shots taken by Saeed the following day. Later Milad, one of two main characters in the film, would say that everyone in Damascus could feel that something big, something horrible had happened nearby. We tried to find a way to relay this feeling to the audience. We decided to gradually remove all the sounds of animals and humans recorded during the shot of the sunrise.

Once I had gained Ghiath and Saeed’s trust, we could uncover the main point of the film. After that, everything else was easy. Five intense weeks of editing later, we had a final cut. The title came when I watched the final sequence of the film right through to the end. The guy who picks up the abandoned camera notices that it’s still rolling, and exclaims, “It’s still recording!”

STILL RECORDING (Saeed al-Batal and Ghiath Ayoub, 2018).

****

A year later, in 2019, Ali offered to fly me to Istanbul to meet Abdallah, who had fled Syria, crossing the border from northern Syria to Turkey by foot a couple of months earlier. Once I arrived in Istanbul, Abdallah explained that he was applying for asylum in Europe. We decided to work on the film once he was settled in Berlin. It would be the beginning of an exciting two years of collaboration, in which Abdallah fully became a director.

The images were hard to watch. But Abdallah, with his charisma and sense of humor, would make the experience less painful than the images and the siege. Under siege, making images was the least important thing to do. In the editing room, I would listen to Abdallah’s stories and ask, “Why didn’t you film that?” In response, he would simply smile. But once, he answered: “I never thought I would get out alive and make a film.”

We didn’t have much material with which to scaffold the structure. Some of the images were so unbearable to watch that including them in the film would have driven audiences out of the cinema without pause. There was also the chronology of the siege that we had to respect.

There’s often more honesty in a director’s first film than in their second, when they are already in control of the tools of cinema and storytelling. Throughout the four bursts of time we spent editing together, Abdallah transformed from a witness and a cameraman into a filmmaker.

But the hardest question to answer remained: What was he filming for? Some of the moments his footage preserved were testimonies by an older generation about their first exile from Palestine in 1948. These videos had value as documents, for the purposes of national memory. There were also scenes showing classes with children or the distribution of humanitarian aid. Those moments were “useful” as proof that certain things continued to happen while under siege. But why film those “useless” moments—scenes that served no obvious purpose? He found so many small moments of poetry, street life, and even simple close-ups of the faces of people in Yarmouk. Those “useless” moments would also be the most useful in sculpting the film.

We wanted to respect the dignity of the people in the camp. The voiceover and the way Abdallah pointed his camera and framed his images were key. For me, the hardest moment in the editing was the scene with Israa, the baby girl who died of starvation. We talked for weeks about the ethics of the scene. I still find it the most difficult part of the film. Seeing her in Umm Mahmoud’s arms is heartbreaking. We made the very difficult decision to keep her in frame, proof of the savagery of a regime still using every means at its disposal to stay in power after ten years of revolution.

LITTLE PALESTINE (DIARY OF A SIEGE) (Abdallah al-Khatib, 2021).

My question—why?—remains unsatisfied. Saeed would say to document crimes; Abdallah would say as proof that this place existed.

My parents hastily left Syria in 2011, with the onset of the popular uprising. They believed the regime would soon fall and they would be able to return. They left everything behind in our family home: pictures, videos, documents. Once, my father received a video from a friend who entered our house and started recording. The images showed a devastated, ravaged apartment. My father didn’t say a word about the images he received. A month later, he died. Everything he’d gathered and captured throughout his life had disappeared under the rule of a tyrant. I don’t know if my family really came from Armenia. There’s no proof of that. And now there’s no proof that we came from Syria. We cannot control time; we can only, briefly, capture it.

Title video: Little Palestine (Diary of a Siege) (Abdallah al-Khatib, 2021).

{1} “James Cameron Teaches Filmmaking,” MasterClass, accessed March 4, 2023, video series, 3:20:00.

{2} Saeed al-Batal, “أحمل الكاميرا كحامل الدرع: لا ينجو من المجزرة، إلا من مات,” Bidayyat, December 30, 2013; translated to English as “I Bear the Camera as a Shield: No One Escapes the Massacre, Except the Dead,” June 5, 2014.