American Glass Factory

Josiah McElheny, Joshua Glick, Julia Reichert, David Roediger, and Julia Lesage

This episode is also available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and Google Podcasts.

Josiah McElheny

I was watching a documentary talking about the reasons why the Twin Towers fell. And I was completely shocked to realize that because of the angle at which you saw the Twin Towers from the ground, you always thought that they were reflective.

Jason Fox

That’s the artist Josiah McElheny.

JM

One of the main designers of the Twin Towers was expressing extreme, deep-seated regret about the design flaws of the towers. They were totally transparent if you were in a helicopter and the sun was behind you, because you could see right through the whole floor. These transparent boxes that were quite literally the world’s greatest monument to moneyed capital flows. They’re called the World Trade Center. And that’s what they were meant to represent.

JF

Josiah doesn’t just think about glass, he also works with it. He makes these meticulously constructed sculptures that almost always incorporate handmade glass in some way. When I first encountered his work in a gallery back in 2015, there was a piece called Crystalline Prism Painting III.

JM

It’s a little bit less than four feet high, and a little bit less than three feet wide. It’s covered in a sheet of museum glass, which is a glass that’s very unreflective. So it looks like it’s almost not there. It’s very dark black with these luminous, colored circles floating in a black field.

JF

I remember being captivated by the blue, yellow, and crystal-white glass prisms embedded in the painting. They give off this almost spiritual glow. But I couldn’t quite tell what I was looking at.

CRYSTALLINE PRISM PAINTING III (Josiah McElheny, 2015).

CRYSTALLINE PRISM PAINTING III (Josiah McElheny, 2015).

JM

They’re sort of pressed and formed in this very complex way in my studio out of glass that refracts. You see this light. It’s almost as if they’re being lit up, like there’s electric lighting, but actually it’s just the light in the room going inside the painting and bouncing around and reflecting back.

We live in an age of reflection and transparency. We don’t live in an age of stone, for example. We don’t live in the age of brick. We live in the age of shiny things, and we live in the age of transparent things.

For me, glass has been interesting as a metaphor, mostly. You know, there’s two ways of talking about it. One is as a material notion, and that’s where it intersects with the visual arts, and with design, and with the history of architecture. And then there’s its purely political meaning. The idea of the access of the citizen to information about what their government is doing is obviously an important concept. At the same time, I think that this idea of total transparency is something that we need to think through more complexly.

JF

Josiah says that a few hundred years ago, mirrors were a real symbol of power in Europe. Think of Louis XIV and the hall of mirrors or the Palace of Versailles.

JM

The king, when he sees himself in the mirror, he knows he’s the king. When he sees other people seeing him in the mirror, he knows he’s the king. And maybe this sounds like a kind of silly philosophical game, but I don’t think so. Because I think this process continues till today, where you have the corporate tower which is reflective and transparent.

JF

This idea of total exposure structures so much of our daily lives. From the way we share, or maybe overshare, our sense of self on social media, to the floor-to-ceiling glass windows on so many of the condos and shops I walk past on a downtown city street. Even to the ways that political leaders are always promising to be more transparent. But sometimes, paradoxically, transparent materials can actually conceal people and ideas.

Take the Netflix headquarters on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, California, built in 2017. It looks like a bunch of irregular-sized blocks that were covered in glass and then just kind of plopped on top of each other. The New York Times called it “the new town hall of Hollywood.” Its 5,000-square-foot lobby is the place to see celebrities and filmmakers intersecting with politicians and musicians. That is, unless you’re hoping to catch a glimpse of former President Barack Obama. I read that Netflix lets its mega-VIPs bypass the glass doors to the lobby so they can avoid being seen coming and going. When Obama recently visited, he entered through a secret underground tunnel that took him right to the employee elevators. I’d love to know what he was there to talk about once it spit him out inside.

I’m Jason Fox, and this is Trust Issues, episode 3: “American Glass Factory.” It’s about new camera technologies and celebrity culture. It’s also about the long-term relationship between documentary, the Democratic Party, and the politics of transparency.

****

JF

About a year and a half ago, I got an email from a friend that had a one-word subject line: “Wow.” There’s no greeting, no “Hi Jason,” or anything like that; just a really long YouTube link. Honestly, it almost looked like spam, but I clicked on it anyway.

Why did you pick our film? There’s a million films out there.

—You let people tell their own story.

I hope that sparks curiosity.

—Gosh, this is fun!

JF

It’s a little jarring, maybe, but not exactly wow.

Why did you decide to do what you’re doing?

One way of looking at what we’ve both been doing for the last twenty years—maybe most of our careers, [once we left law]—was to tell stories. If you want to be in relationships with people and connect with them . . .

—American Factory: A Conversation with the Obamas (2019)

JF

You might immediately recognize some of those voices. But it took me a minute to figure out what I was looking at. Michelle and Barack Obama are sitting on one side of a bistro table at an empty retro diner. The sleeves on Obama’s dress shirt are rolled halfway up his forearm in a way that suggests he’s ready for a frank conversation. And on the other side of the table are the filmmakers, Julia Reichert and Steve Bognar. It’s a coffee date, but none of their mugs appear to be filled with coffee. The video is a promo for Reichert and Bognar’s documentary American Factory (2019). After it premiered at Sundance, the Obamas had acquired it through their new entertainment business venture, Higher Ground Productions.

Those first scenes of those folks on the floor in their uniforms. That was my background. That was my father. And that was reflected in this film.

—Michelle Obama, American Factory: A Conversation with the Obamas

JF

American Factory follows the reopening of an auto glass manufacturing plant in Dayton, Ohio. It captures the struggles of the American factory workers as they adjust to their changing working conditions under new Chinese management. They try, and fail, to unionize. The film won an Oscar for Best Documentary in 2020.

But back to the original wow. I think the reason my friend sent it to me is that Reichert and Bognar aren’t exactly the kind of filmmakers you’d expect to see having a no-coffee coffee date with the Obamas. Like, Reichert is the filmmaker behind Growing Up Female (1971), a pioneering film of second wave feminism.

Uh, my girlfriends, well once I got married, I could no longer, you know, spend all the time with them giggling about other guys, because I had my own husband to take care of and I sort of became a loner.

—Growing Up Female

JF

Her Seeing Red (1983) looks at the American communist party in the years leading up to the Cold War.

Are you a member of the communist party?

I would give you the same answer I have given the FBI, the Red Squad, the police department, everybody else: that is just none of your business!

—Seeing Red

JF

In Reichert’s Union Maids (1976), three women talk about battling sexism and racism as organizers in the Depression-era labor movement.

The roofs in New Orleans were put on with slate. It’s a skilled job, not anybody can put on slate.

—Union Maids

JF

It’s worth mentioning that Reichert herself wouldn’t hesitate to call herself a Marxist, which is why seeing them all at the table together feels like a bit of a strange union. So strange, that it’s been in the back of my mind for about a year and a half. I’m still stuck on this one question that Reichert asked the Obamas during their chat.

You guys could do whatever you want. Why did you decide to do what you’re doing?

—Julia Reichert, American Factory: A Conversation with the Obamas

JF

The former president really could do just about anything, and he invests in the work of a self-described Marxist-feminist? What’s that about? I asked Josh Glick. He’s a film industry scholar based in Little Rock.

Joshua Glick

I mean, I think the Obamas were sort of looking for a way to stay involved in public life and to meet as many people as possible where they’re at. It allows them a certain kind of flexibility to be producers, essentially, it allows them to move across genres, across platforms, across media. Also, I think it’s a way for them to think about their legacy a bit. I mean, through American Factory, and through their larger work in media, there’s a tremendous amount of power to be gained with working with companies like Spotify or Netflix to shape how people think about his presidency, and how people think about things like civics and electoral politics going forward.

JF

Part of it is that Obama is expanding on some of the ideas of his presidency long after it ended. The other part is the obscene amount of money.

JG

I don’t know the exact dollar amount for their Netflix partnership, but it’s a very high figure. Just to give you a kind of ballpark. I mean, for folks like Shonda Rhimes and others, we’re talking, like, 100-million-dollar deals.

JF

OK, but why acquire American Factory? Josh said it was perfect for the Obamas’ brand. It’s timely and topical. It features transnational forces playing out in the daily lives of working Americans in the Rust Belt. If you want to see class conflict, it’s in there. But if culture clashes are more your speed, you can see the film that way too. You decide. In the film’s marketing, Higher Ground uses the tagline “Cultures collide, hope survives.”

If you know someone, if you talk to them face to face, if you can forge a connection, you may not agree with them on everything. But there’s some common ground to be found, and you can move forward together.

—Barack Obama, American Factory: A Conversation with the Obamas

JG

It’s trying to show how they would hope the film is discussed—or how media is discussed, how politics is discussed—in homes, in neighborhoods, in communities across the country.

JF

But it’s not just that. The partnership kind of makes sense for Reichert and Bognar too. They’re filmmakers invested in social movements. And this allowed them to potentially reach a new, wider audience than they had before. Talking to Josh made me wonder if American Factory is more than just another film in the Obamas’ new entertainment portfolio. Maybe it’s also intended to be a sort of presidential portrait of Barack Obama. Like, not the official portrait. That’s hanging in the National Gallery. I mean it more in the sense that American Factory is a film that depicts a struggle to reconcile racial, political, and economic contradictions of American life. And that’s kind of how Obama narrated his presidency, as a unifier. Besides that, documentary can shape Obama’s legacy by letting him be seen as someone who’s transparent, and someone who casually reflects the values of the people he represents.

I’m sure that Reichert and Bognar didn’t intend for the film to become one of many unofficial portraits of a postpresidency Obama. But there has been a long relationship between the direct cinema documentary movement and the US Democratic Party. That relationship produced a lot of unofficial, and typically lionizing, portraits of Democratic candidates. Those arrangements were mutually beneficial too. Direct cinema brings authenticity and transparency to the Democratic Party. And in return, the Democratic Party provides charismatic candidates and dramatic tension in the form of high-stakes election campaigns. But to really understand the relationship between documentary and the Democratic Party, we need to go back to the decade before Reichert’s career began. And before Obama was even born. We need to go back to 1960.

****

JF

The motion picture camera has been with us for roughly 125 years, give or take. But it’s only for the last sixty years that cameras can do the thing that we take for granted. When you press record on a video camera, sound usually gets recorded too. But up until about 1960, you had to record sound in a studio because the equipment was just too heavy to carry around. So documentaries often sounded like this:

They are the migrants, workers in the sweatshops of the soil.

—Harvest of Shame (1960)

JF

It’s a CBS News report called Harvest of Shame, from 1960. We’re looking from above at rows and rows of newly planted crops. But more important is what the scene sounds like. It sounds scripted, because it had to be.

It has to do with the men, women, and children who will harvest the crops in this country of ours, the best-fed nation on Earth.

JF

A writer for Life magazine named Robert Drew was frustrated by that constraint. So he gathered a team, and they came up with an idea. If you took the same kind of quartz crystals that were used in watches and put them in your film camera and your sound recorder, they could stay in perfect sync. Suddenly cinematographers were free to roam. Documentarians no longer had to follow scripts. People could be themselves on camera.

There’s probably a video camera attached to whatever you’re using to listen to me right now. And in a way, this is the beginning of all that, the beginning of the idea that everyone is inherently interesting, everyone has a story to tell, and portable cameras allow people to tell them. Here’s Bob Drew talking about what it all meant for his work.

Robert Drew

OK, this is Bob Drew, clap six. It was my idea that television journalism should be more human and spontaneous and more involving. The reason all documentaries were dull, basically, mostly, is that they were lectures.

JF

Albert Maysles, an emerging filmmaker who would go on to document Marlon Brando, the Rolling Stones, and Muhammad Ali, immediately understood the potential for cinematographers. You could actually carry the camera around on your shoulder and it’d be quiet.

Albert Maysles

The sound would be of excellent quality. It would be in sync with the picture. You could let the story tell itself. That was the revolution that got us all excited.

JF

The revolution became known as direct cinema. And there was an awful lot of talk about liberation. But these revolutionaries weren’t that interested in politics. So it’s kind of funny that the first time they put this technology into practice was to follow an up-and-coming senator from Massachusetts who was running for president.

Here’s Ricky Leacock, one of Drew’s collaborators, speaking at the Flaherty in 2004.

Ricky Leacock

And in my very limited view of politics at the time, I thought Kennedy was too rich and his father was a fascist . . . blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. That was the opinion. Anyway, Drew got me to go up and talk to Kennedy.

JF

He’s talking about John F. Kennedy, by the way.

RL

And he said, “We have to have agreement, that you alone can be in Kennedy’s private room when he listens to the results of the election.” And we talked to Kennedy down in Washington, and Kennedy finally agreed. He said, “If you don’t hear to the contrary you can be with us there.” I said, “No lights, no tripods, no cables, no questions, no interviews, no nothing. Just let me into the room.” And I didn’t know how the hell I was going to do it.

JF

Bob Drew wasn’t so modest.

RD

The first story I picked was a young senator running for president in Wisconsin. It turned out to be Primary, and Primary turned out to be a film that changed everything in filmmaking.

JF

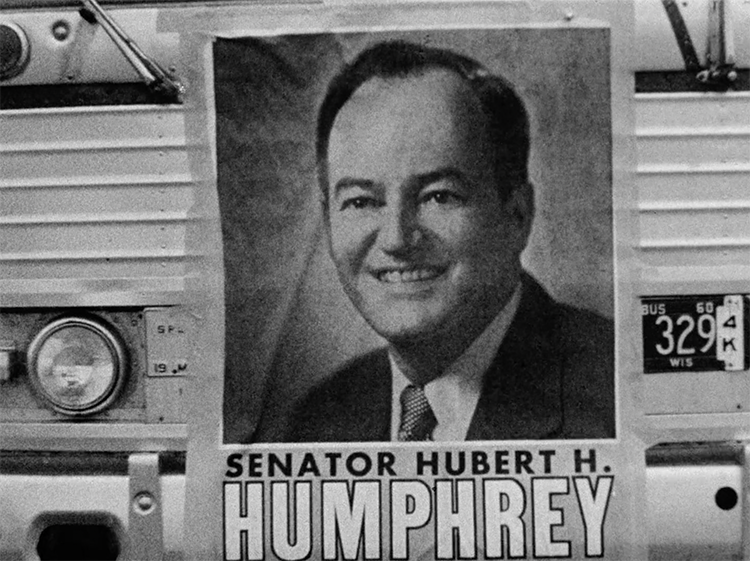

Bob Drew’s 1960 film, Primary, follows JFK and Hubert Humphrey, Kennedy’s opponent in the 1960 Democratic primaries, as they campaign for votes across the state of Wisconsin. The film isn’t just about the rise of a young politician to the highest office in the land. It’s also, for Robert Drew and Albert Maysles and Ricky Leacock, the coronation for a whole new way of seeing the world onscreen.

An early scene opens with a tightly framed still photo of Hubert Humphrey. It feels like the kind of static image convention that documentaries use all the time. Then the camera starts to pull back, and we realize we’re not just looking at a still photo. It’s actually Humphrey’s face plastered on the front of his campaign bus as we barrel down the rural Wisconsin highway. And right off the bat, the film is telling us that documentary can do more than just describe the world. It can let us experience it for ourselves.

PRIMARY (Robert Drew, 1960).

PRIMARY (Robert Drew, 1960).

JF

The film cuts to a new location. Now we’re moving with Kennedy. We’re looking just over his shoulder as he parts a sea of supporters on his way to the stage. Now we’re onstage with him as he looks out onto the crowd.

Primary begins a new chapter for both American documentary and the US Democratic Party. Primary isn’t just about documenting a political campaign. It’s about a new generation of filmmakers capturing a new generation of politicians. The direct cinema guys talk about their work like it was a window on the world; as if it just recorded reality. But their films also shaped how we see the world, and how we still relate to politics in some pretty significant ways. Watching Primary, I count five formal conventions that will shape the relationship between the two institutions for decades to come.

Convention #1: Circumstantial events eclipse institutional pressures. Remember Ricky Leacock’s story about how he approached JFK? It’s a world where anyone could happen upon a Kennedy at a party. And then they might just happen to talk about making a movie together.

Convention #2: The world is made up of underdogs and comeback kids.

JF

It’s kind of hard to remember now, but Kennedy’s Catholic faith was an electability issue. This makes him an underdog, and that makes for a good story.

Convention #3: The cult of charismatic individuals who always maintain grace under pressure.

This is the key office, and I run for the presidency because, like you, I have strong ideas about what this country must do. I have strong ideas . . .

—John F. Kennedy, Primary

JF

The camera looks up on Kennedy’s iconic side profile as he speaks. Not one hair is out of place, not one bead of sweat on his brow. He’s in a packed auditorium speaking to hundreds of supporters, but through the lens of the camera, it’s just him.

. . . we can see the campfires of the enemy burning on distant hills. That’s what’s at issue today. That’s what we are attempting to determine. In the coming months and years, all of us as Americans are going to be called on . . .

—John F. Kennedy, Primary

JF

There are main characters in direct cinema, but never stereotypes. Characters are uniquely individual, and true individuals take problems into their own hands.

Convention #4: There’s always a scene of the candidate critiquing the mainstream media. The idea of fake news isn’t new. There’s a long history of campaigns characterizing the press as elitist, out-of-touch relics from the past. Here’s Hubert Humphrey stumping to a gymnasium full of Wisconsin farmers.

Instead of you reading about who you want to have as president in Life magazine, you ought to take a good look at him in the flesh. You ought to hear what they’ve got to say, because let me tell you something: Life, Time, Fortune, Look, and Newsweek don’t give a hoot about your dairy prices. And I know they laugh at you. I’ve been down to their editorial board, some of them, and I’ll tell you, they have no more appreciation of a farmer’s problem than they have of what’s going on on the other side of the moon. Frankly, they don’t know the difference between a corncob and a ukulele.

JF

Even in 1960, invoking a corncob-ukulele comparison probably wasn’t the best way to demonstrate you’ve got your finger on the cultural pulse. But you get the point.

The fifth, and the last, convention comes from behind the camera. Let’s call it the naive filmmaker convention. The naive filmmaker is someone who isn’t wedded to preconceived notions about the way things are, because they don’t know too much about the way things are. Like when Ricky Leacock described his view of politics as “limited.” Or like when Bob Drew said that the first door he “happened to pick” was of a young senator. This last convention, the one about the naive filmmaker, is one that would be repeated again and again by direct cinema filmmakers themselves.

Years ago, I was at a screening of a concert film made by another filmmaker who worked on Primary, D. A. Pennebaker.

Ladies and gentlemen, straight from his fantastically successful world tour, for the last time, David Bowie!

—Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1973)

JF

It was Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, a film he’d made with David Bowie. And during the Q&A, I remember Pennebaker saying that he’d never heard of Bowie until he got a call about the film, grabbed a camera, and hopped on a plane to London to meet him. And Pennebaker wasn’t the only one. When Albert Maysles talked about how he and his brother ended up making a film about a bunch of upstart musicians from England . . .

AM

They said the Beatles were arriving in two hours in New York at Idlewild Airport. Would we like to make a film of them?

JF

Albert insisted that he’d never heard the names John Lennon or Paul McCartney until he met the band at the New York airport in 1964.

AM

I put my hand over the phone, and turned to my brother and said, “Who are the Beatles? Are they any good?”

WHAT’S HAPPENING! THE BEATLES IN THE U.S.A. (Albert Maysles, David Maysles, 1964).

WHAT’S HAPPENING! THE BEATLES IN THE U.S.A. (Albert Maysles, David Maysles, 1964).

JF

Happenstance is everywhere in the mythologies behind these films. There are no structural barriers in a world where anyone can walk up to a Kennedy at a party. Or if there are barriers, it’s probably because you’re not charismatic enough (refer to convention #3).

Primary isn’t just the start of the direct cinema movement. It’s also the start of a direct cinema subgenre of films that feature major Democratic Party politicians. Bob Drew made three follow-up films with Kennedy when he was in the White House. And then there was The War Room (1993), a behind-the-scenes look at Bill Clinton’s improbable 1992 presidential victory.

Another good night for Bill Clinton. Three debates, three wins. Bush was on the defensive all night long. I think he was put on the defensive by Bill Clinton over the economy and by Ross Perot over Saddam Hussein . . .

—George Stephanopoulos, The War Room

JF

There’s also Spike Jonze’s little-seen portrait of Al Gore in 2000, in which Gore’s daughter Karenna gives us a tidy example of convention #4, critique of the media.

I think that my dad doesn’t feel entirely comfortable in today’s contemporary political culture. And in terms of kind of the whole kind of celebrity of it. Lights, camera, action. You know, soundbites.

—Karenna Gore, Untitled Al Gore Documentary

Karenna Gore in UNTITLED AL GORE DOCUMENTARY (Spke Jonze, 2000).

Karenna Gore in UNTITLED AL GORE DOCUMENTARY (Spke Jonze, 2000).

JF

There’s 2005’s Street Fight, following Cory Booker’s first campaign for mayor of Newark, New Jersey.

I’m Cory Booker. You ever hear my name? Cory Booker. I’m not sure if you’ve heard of me, but I’m the city councilman from the central ward, but now I’m running for mayor.

—Cory Booker, Street Fight

JF

And there are more. These aren’t just films about prominent politicians. They’re also films that brought prominence and acclaim to the filmmakers’ careers. In a way, these filmmakers are a mirror of their subjects. Like Kennedy, these filmmakers didn’t really see themselves as fighting against institutions. More like transcending their limits.

****

JF

About ten years after Primary, Julia Reichert released her first film, Growing Up Female, at the height of the direct cinema movement. But Reichert wanted to take documentary in a different direction. Unlike the direct cinema pioneers, Reichert never wanted to sidestep institutions. She wanted to confront them.

Actually, they’re secretaries. They call her mother two or three times a day. They’ve got a lot of hang-ups.

—Growing Up Female

JF

Growing Up Female is Julia Reichert’s first film. Six women, aged four to thirty-five, talk about their personal experiences, their goals, and their frustrations.

Tell me, who’s a woman you admire?

One of the women I most admire is Elizabeth Taylor.

—Growing Up Female

JF

In this scene, we see a middle-aged TV producer with a wide mustache and thick-rimmed dark glasses. He’s in his living room, lounging in a mid-century swivel chair. He stares into the distance to respond to Reichert, who’s just off camera, and he shares his thoughts on what women want.

Women are always living in a dream world. They’re attempting to escape from the humdrum reality of America to exotic lands. I remember one time we handled a tutti-frutti, super-duper, dubble-bubble soft drink commercial. It was set in a Tahitian setting. There were dancing girls and fellows climbing coconut trees, and the girls just ate it up.

JF

When I think back to watching Growing Up Female for the first time, it’s less the content that I remember. It’s more the feeling of watching it. It made me want to make films with the same kind of sharp political analysis. And I was struck by the care Reichert brings to interviewing. Most of the film’s subjects talk about who they understand themselves to be, not just how they’re oppressed.

Because so far, I can only judge marriage by my friends, in their relationships with their wives or husbands. And it seems to me that the institution of marriage is a farce.

—Growing Up Female

JF

If these ideas feel familiar today, it’s only because of the work people like Reichert were doing fifty years ago.

Julia Reichert

See, we’re trying to make a film about what the experience of women is, and magazines and television are just as much reality as me asking a question, or as them answering a question, I feel. If we just left out entirely any reference to advertising, we would have left out a very important influence on women.

JF

For Reichert, you can’t just dodge the influence of television and magazines any more than you can dodge your landlord. Women would need more than just lightweight cameras to break free. But not everyone agreed that Growing Up Female was so groundbreaking. In 1971, Reichert and her codirector, Jim Klein, were invited to screen it at the Flaherty Seminar. One of the attendees accused the filmmakers of feeding lines to the ad producer to suit their agenda.

The guy is sort of set up, I mean, your advertising man, because what you’re saying in the film is the way human beings get ripped off . . . women. And that’s very important that you work that out for me and say more about it, like, how much did you feed him?

—anonymous voice, 1971 Robert Flaherty Film Seminar

JF

He assumed that because Reichert and Klein chose sit-down interviews instead of following subjects around it meant everything was staged. But the real reason is that it’s just cheaper. The more controlled the setting, the less film you have to use. Someone else had a suggestion for how they could have saved money instead.

And maybe if you had an hour’s time and, you know, a limited amount of money, it would have been better to maybe concentrate on one group instead of six. I mean, I don’t think there’s a right or wrong answer. But if you could explore it, maybe you could get to say what you want to say better. Because a film isn’t a sociological document.

—anonymous voice, 1971 Robert Flaherty Film Seminar

JF

Listening to this comment from the seminar, I wondered what this person meant when he said, “A film isn’t a sociological document.” So I asked Julia Lesage, a feminist film scholar who’s also an old friend of Reichert’s.

Julia Lesage

I have heard leftists speak like that, particularly in that era. The accusation of “sociological” is something much bigger. It’s something like “I cannot stand to see your pain, even though you present it to me, because I can’t stand for it to be revealed to me, that which I prefer to not have to pay attention to.”

JF

I said that Growing Up Female is about the institution of patriarchy. But it’s really about an institution that insists it doesn’t even exist. In response to their experience at the Flaherty, Reichert and Klein cofounded New Day Films, a documentary distribution cooperative that would support feminist filmmakers, and support the movement. It wasn’t just about making political films. Their politics also informed how they made them.

JL

Julia and Jim lived in a collective household. And they really lived the notion of collectivity. If you were part of New Day, you had to work in administration in a collective way. You had to commit yourself to certain tasks and a certain number of hours and a certain amount of work. Nobody got into New Day just to have a distributor. Lots of theater groups and art groups and music groups were into collectivity in the 70s. But you know, they didn’t last.

JF

It’s not that these filmmakers just stopped making work once the 1980s came around. And it’s not like organized labor and feminism stopped being a concern. It’s more like: the political winds turned. Trade unions and collectives of all kinds were suffering, and the Democratic Party didn’t know how to steer in a different direction. Meanwhile, Bob Drew, the Maysles, and Pennebaker were still mostly making films about famous people.

Here’s Pennebaker.

DP

Somebody called up and said . . . I think it was their manager in New York. I don’t know who he was, now I forget. But he said, “Would you like to do a film about Depeche Mode, with Depeche Mode?” And I had no idea what they were talking about.

DEPECHE MODE 101 (David Dawkins, Chris Hegedus, D. A. Pennebaker, 1989).

DEPECHE MODE 101 (David Dawkins, Chris Hegedus, D. A. Pennebaker, 1989).

****

JF

For years, the party had no coherent electoral platform to offer, no charismatic outsiders to embody it, no documentaries to capture it. Then, in 1992, D. A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus returned to the world of political campaigns, embedding themselves with the media masterminds behind an insurgent candidate’s improbable win.

. . . James Carville is known as the Ragin’ Cajun in the business. And we’d like him to say a couple of words to you.

—The War Room

JF

The film they made is called The War Room. It’s often referred to as a “buddy movie,” because it doesn’t focus so much on the candidate. Instead, the camera goes into the back room where campaign directors James Carville and George Stephanopoulos are designing Clinton’s march to the White House. Here’s Carville rallying the troops at one of Bill Clinton’s New Hampshire campaign offices.

Let me tell you what’s at stake in this election. Every time that somebody comes along that’s got some ideas—a Democrat comes along—the Republicans come up here and ambush him. Remember Muskie? OK, that is standard procedure. And here comes Clinton. He comes to New Hampshire; people here are hurting, they want hope. They want somebody with vision. He gives it to them.

—James Carville, The War Room

JF

And he goes on to talk about media executive Roger Ailes.

It’s going to come out that Roger Ailes is behind a lot of this stuff before the election that you’ve been seeing about Governor Clinton, OK? Ailes.

—James Carville, The War Room

JF

Pennebaker and Hegedus explained that they could have recorded more with Clinton, but they felt like the candidate would treat them like just another news team. And they didn’t want to just repeat the news.

Here’s Pennebaker again.

DP

They give you the access, but what you hear, it’s not the true gossip. You want to get behind what you hear and find out what people do tell each other and what really drives the train. And you don’t get that sitting on the front porch.

JF

Pennebaker and Hegedus pull back the curtain, and what they reveal is another curtain. Behind that curtain, we feel like we’re getting to watch a president being made. But what appears transparent from one angle is opaque from another. That feeling of backstage access we get from seeing Carville and Stephanopoulos at work? It’s actually hiding someone else.

There’s another, less gregarious figure who’s also working behind the scenes of Clinton’s campaign. He makes only the briefest of appearances in The War Room, wearing characteristically 1990s Dockers and oversized glasses. He’s a pollster, and his name is Stanley Greenberg.

Stan Greenberg, where are you?

—There’s going to be a poll that’s going to come out which we did jointly. It’s going to show extraordinary changes on the favorabilities. It shows us with favorable . . . with a balance . . . a net positive favorable of about 10 points more favorable. Bush more negative . . . net negative by about 10. And Perot even fave/unfave at around 37. So that represents good 6-point change, or more. Obviously, we’re doing something right.

JF

Greenberg hunches his shoulders when he talks. And he’s almost always hidden by the stack of file folders and printouts he’s got under his arm. But historian David Roediger argues that, in fact, he’s the real behind-the-scenes star of the Clinton show. Here’s Roediger on how Greenberg became the architect of the campaign.

David Roediger

He’s invited by the Automobile Workers Union and the Democratic Party into Michigan to try to investigate why Democrats have lost working-class voters in that state; white working-class voters. And he seizes upon this little suburban county called Macomb County, outside of Detroit. And in studying Macomb County, he comes to argue that this nearly all-white county at the time was the key to the fortunes of the Democratic Party.

JF

By the way, Macomb County is reliant on auto manufacturing just like Dayton, Ohio, the city three hours to the south where American Factory was shot. Greenberg thought that if the Democrats couldn’t win Macomb County, then it’d be proof that they’d lost their connection to the white working class. And without them, they couldn’t possibly win an election.

DR

He does focus group polling among all-white groups in Macomb County. And he then reports to the union, and especially to the Democratic Party itself, that in order to recapture these so-called Reagan Democrats, as they were being called at the time, and bring them back into Democratic voting, it would be necessary to soft-pedal issues like busing and to be responsive to white views on welfare and on defunding education, and especially on crime, to court the Reagan Democrat as both a white worker, but, as was more often said, as a member of the middle class.

JF

Those Reagan Democrats are the white, male trade union workers who’ve been voting Democrat since the New Deal in the 1930s. But in recent years, they’ve been feeling overlooked. So, they supported Reagan instead. Greenberg discovered that there were two reasons the Democrats had lost their support. The first was that Democrats couldn’t save union jobs from going overseas. The second was the feeling that maybe Democrats could have done something about it if they weren’t so focused on things like civil rights or immigration or providing welfare. So Greenberg offered a key piece of advice: You are appealing to white workers, but you can’t say the words white or workers. You have to address them as members of the middle class.

DR

He argues that the white working class, which he now calls “middle class,” has to be paid attention to by the Democrats in a way that doesn’t require that any labor demands be met, or any fair trade demands be met.

JF

But what is the middle class? We tend to talk about it like it’s an economic fact. But it was meant to be a sleight of hand. It’s not tied to a particular income bracket. And no one much mentioned “saving the middle class” until Clinton came along. It’s an aspiration. The middle class is the class for people who hate the whole idea of class. The middle class is white suburban anger at their declining standard of living and anxiety about rising crime. Greenberg teaches Clinton to tap into the racial resentments of white people who are feeling forgotten. That’s the real story, but that’s not the real story that The War Room tells. Here’s how Hegedus and Pennebaker responded to criticisms that they went too soft on the Clinton campaign.

DP

What did we know about politics? Nothing. We’re like buddies ourselves, so they appealed to us, not because we understood their smart political gestures. We understood that they understood how to work with each other. They filled each other in in a way that was so incredibly working that you couldn’t not make a film about it.

JF

In other words, they’re just filmmakers with a good eye for odd couples. If you don’t know anything about politics, you don’t bring your political baggage to the film, and the film can just reflect the world as it is. For the late film theorist Paul Arthur, the naive filmmaker isn’t just a convention of direct cinema. It’s the engine behind it. His theory goes like this: Because these filmmakers show events but don’t analyze them, viewers are free to come to their own conclusion about what’s onscreen. In other words, direct cinema isn’t your dad’s documentary, where a stodgy narrator is telling you what to think, kind of like I’m doing now.

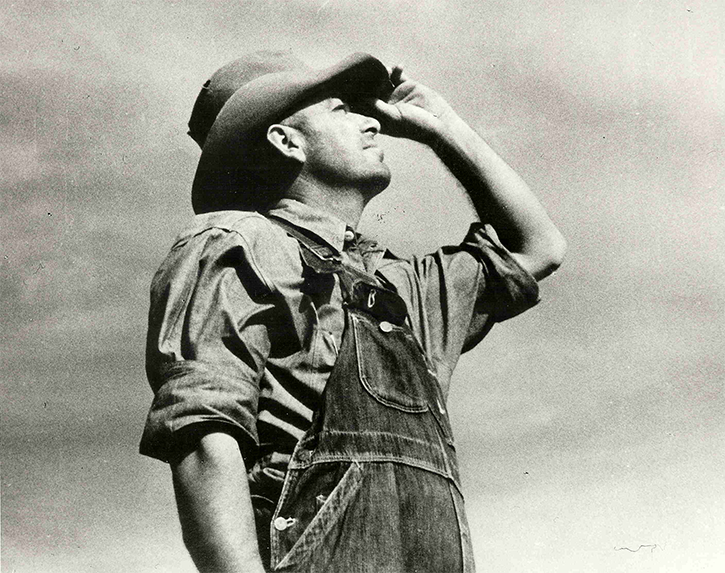

Imagine watching a government-sponsored documentary from the 30s. Imagine it contains a shot of a solitary farmer standing in his field, wiping the sweat and the dust from his brow. Now imagine a voice, deeper and warmer than mine, that says, “Farmers of the Tennessee River Valley work hard for their harvest.” See how one farmer is made to stand in for a whole group? And how my voiceover is telling you how to see the image? That’s the opposite of the direct cinema approach. In direct cinema, documentaries merely observe. They observe specific people in specific and singular circumstances. And because they are so specific and so singular, a whole bunch of people can watch the same film and walk away with totally different interpretations. You can debate about the film with your friend, but you can’t fundamentally disagree about it any more than you can the fact that the sky is blue. Ex uno plura. Out of one, many.

THE PLOW THAT BROKE THE PLAINS (Pare Lorentz, 1936).

THE PLOW THAT BROKE THE PLAINS (Pare Lorentz, 1936).

JF

Pennebaker and Hegedus make a film about two guys who come together to get a man elected president. Greenberg makes a campaign about how one county’s concerns around race and class are actually a narrative of possibility. He gets a man elected president. Both narratives play pretty well. They begin with specific facts, but those facts are easily absorbed by older narratives about the essence of America. From the Dayton, Ohio, of American Factory to the Wisconsin farmland to Primary to the Macomb County of Stanley Greenberg, we’ve gone backwards and forwards in time across more than half a century, but we haven’t actually traveled very far. In fact, we haven’t even left the American Midwest, the region presidential candidates like to call “the heartland,” or “real America.” These three places form a triangle small enough that you could drive all three sides in a day. But the narrative possibilities seem endless. And inside that triangle is Chicago, the political home of President Barack Obama.

****

JF

Barack Obama never really got the direct cinema portrait he deserved. I mean, there is one. It’s called By the People (2009).

I believe the American people are tired of fear, and tired of distractions, and tired of diversions. We can make this election not about fear, but about the future. And that won’t just be a Democratic victory. That will be an American victory.

—Barack Obama, By the People: The Election of Barack Obama

JF

It follows Obama as he campaigned for the presidency between the summer of 2007 and his election in November 2008. It’s not very memorable, though, which is too bad because if anyone is a great candidate for the direct cinema treatment, it’s Obama. Obama the underdog. Obama the charmer, the self-made brand.

Hell, I myself was too complicated, the contours of my life too messy and unfamiliar to the average American, for me to honestly expect I could pull this thing off.

—Barack Obama, A Promised Land (2020)

JF

That’s Obama reading from his new book, A Promised Land. It sort of seems like “average American” means what Greenberg meant when he said “middle class.” White people. He embodies the diversity of American life: black and white, progressive and conservative, secular and religious. A lot of people weren’t just voting for him, but for the hope, or maybe the fantasy, of a postracial country.

My having been elected president was proof that the American idea endures.

—Barack Obama, A Promised Land

JF

In a way, Obama is doing a bit of what the naive filmmaker does. But it’s more complicated than that. He isn’t naive about politics. And he’s not naive about what drives political change. But still, he presents himself as proof that the problems of race, culture, and class can be transcended rather than confronted. You don’t need to take a strong ideological stance, just meet in the middle.

But let’s get back to that initial “wow,” and the question of why Obama moved from politics to entertainment. Maybe it’s because he didn’t actually have to go anywhere, because politics and entertainment aren’t as separate as we make them out to be.

We all have a sacred story in us, right? A story that gives us meaning and purpose and how we organize our lives. If you know someone, if you talk to them face to face, if you can forge a connection, you may not agree with them on everything. But there’s some common ground to be found, and you can move forward together.

—Barack Obama, American Factory: A Conversation with the Obamas

JF

Maybe the Obamas aren’t investing so much in the content of Reichert and Bognar’s film as the form of it. Maybe what they’re investing in is the ideal that direct cinema upholds. And the idea that by focusing on particular people in specific moments, you can create something cosmically grand, a coffee shop large enough for everyone to gather and exchange ideas. They’re kind of modeling it in the promo. It’s a model that favors individual personalities over collective movements, which is startling, because what Reichert’s films have taught me is that the personal is political only when it’s the starting point for collective action.

An unofficial presidential portrait isn’t the project that Reichert and Bognar set out to make, but it may be what the Obamas saw in American Factory. Because the thing is that even though filmmakers have some control over the shape and the intentions of their films, individual decisions and intentions can never account for how those films will then live in the world.

The feeling of transparency gives us a sense of control. But sometimes, it’s just a trick of perspective. Between the years 2016 and 2020, a lot of Americans lamented the Republican “reality TV” presidency of Donald Trump. You know—reality TV, as like a thin and cheap sketch of reality, too exaggerated to actually resemble reality. But we don’t hear as much about the other side of the electoral cliché; the one about the social documentary Democratic president. The one that says with enough progress, everyone can earn the right and the ability to be seen. And maybe that’s why Reichert and Bognar partnered with one of the most famous political couples in the world—to get their story noticed. Because if we’re just a bunch of individuals telling our own unique stories, then that’s going to make for a lot of content, and you’re going to need pretty powerful partners to elevate your story above the crowd.

Sixty years after Primary, we’re still investing in a world of more and more exposure. But maybe you don’t want total exposure. Maybe you want more control over how you’re seen and remembered. And so you leave the Netflix headquarters through that secret tunnel for VIPs, the same way you came in.