A Skin We Share

Daniel Berndt

When on August 4, 2020, 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate stored at the port of Beirut exploded, the premises of the Arab Image Foundation (AIF), located only eight hundred meters away, suffered extensive damage. Its offices and library were turned into a mess of broken furniture, debris, shards of glass, and scattered books. The foundation’s cold storage room—which houses more than 500,000 photographs, including holdings from Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, Palestine, Syria, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Algeria, as well as Mexico, Senegal, and Argentina, one of the largest collections of vernacular photography in the MENA region—was completely destroyed. While, miraculously, all of the photographic objects remained intact, the explosion prompted the AIF to explore new options to keep the collection safe.

Since its inception in 1997, the foundation has mostly relied on the support of international cultural organizations, private donors, and corporate grants. Lebanon’s ongoing economic and political crisis, which flared up in 2019, intensified the AIF’s financial precarity, but it was the explosion that posed even greater existential questions regarding its prospects and its mission to preserve and study the photographic heritage of the Arab world and its diaspora. The preservation of historical photographs is, for the AIF, as much an act of conserving and documenting as it is a way to activate links between generations. It offers a means of looking at once forwards and backwards—from an uncertain future to a conflict-ridden past.

The AIF began its effort to preserve local amateur and studio photography at a time when vernacular photography was being described as “a lacuna in photography’s history, an absence.”{1} While fine-art and journalistic photography had long ago made their way into museum and other institutional collections, historical vernacular photography was often excluded as “illegitimate” or “middle-brow,” its importance to cultural memory only marginally acknowledged.{2}

By focusing on vernacular photography, the AIF set itself the task of emphasizing the social and historical value of this photographic heritage for the region. In view of its location and the historical context in which it was established, one could say the AIF was also created in response to the devastating destruction of Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War and to the lack of cultural institutions and museums in Lebanon in the late 1990s. The foundation’s approach is characterized by a particular urgency, as it seeks to generate critical thinking about vernacular photography in relation to shifting questions of identity, history, and memory.

By the late 1990s, more and more photo studios throughout the MENA region were disappearing. In countries plagued by armed conflict, such as Lebanon and Iraq, many studios and private collections were destroyed or abandoned. An older generation of photographers, who often couldn’t keep up with the constant innovation in photo and print technology, had either already retired or were gradually closing up shop. Studio archives were off-loaded at flea markets or simply dumped on the street. At the same moment, digital technology was increasingly changing the social practice of photography and the distribution of knowledge around it. These were the crucial parameters that sparked the AIF’s drive to collect and digitize studio portraits, private snapshots, and family photographs across the region.

The projects and artworks realized over the years by AIF members convey the particularities of different photographic practices, at different times and in different places. They employ personal accounts and oral testimonies to contextualize photographs and show how photographic practices in the Middle East were influenced by social and religious norms as well as current trends and fashions. They give an impression of how photography in the region evolved, from the impact of early colonial photographers in the nineteenth century to the first generation of local studio photographers; from a time when being photographed was the preserve of a privileged few to later decades like the 1920s, when photography became a popular commodity, and the 1950s, when it evolved into a widespread hobby. This evolution goes hand in hand with technical innovations—from large-format cameras, daguerreotypes, and glass plates to 35mm film; from black-and-white to color and instant photography—and how these affected different generations and their attitudes toward the medium, as well as their access to it.

With their projects, AIF members have continuously emphasized the pivotal role photography has played in stimulating and solidifying ties across generations, in contributing to the formation of collective identities, and in constructing a counterimage to the hegemonic pictorial rhetoric of orientalist photography by offering a complex image of modernity in the Middle East.{3}

The work of contextualization rests at the core of all AIF projects. In line with Roland Barthes’s notion of the photograph as an “umbilical cord,” “a skin” that we, the beholders, “share with anyone who has been photographed,” photography is treated by the AIF as a kind of inter- and transgenerational tissue.{4} But what exactly happens when personal photographs, once primarily memorabilia for different generations within the closed circle of a family, are considered cultural heritage and become meaningful for society at large? How does the AIF negotiate between the affective capacities of images on the one hand and their significance as artifacts and historical documents on the other? And what roles do digitization, documentation, media transfer, and remediation play to ensure these images’ validity as transgenerational links?

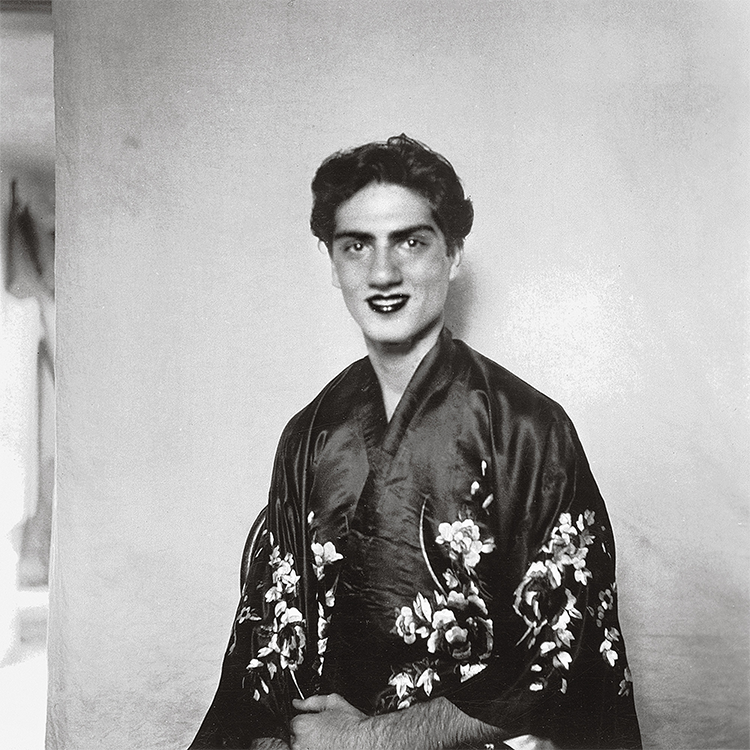

Van Leo, self-portrait, Cairo, June 26, 1940. Courtesy of the AIF.

Van Leo, self-portrait, Cairo, June 26, 1940. Courtesy of the AIF.

For the AIF, collecting, documenting, and safekeeping serves its project of transferring knowledge. The archive is not a hermetic entity. Rather, it’s a platform for dialogue between generations. The form of intergenerational exchange it facilitates also takes place within the organization of the AIF itself: its founding and early members Akram Zaatari, Fouad Elkoury, Samer Mohdad, Walid Raad, Lara Baladi, Yto Barrada, Jalal Toufic, and Issam Nassar were over the years joined or replaced by younger artists and researchers like Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh, Vartan Avakian, Cumaea Halim, Hrair Sarkissian, Fabiola Hanna, and Kristine Khouri. The changeover from founding members to current members of a younger generation resulted in fundamental (re)negotiations of different approaches, concepts, and viewpoints regarding photography and its relation to memory and history, as well as to broader issues like the politics of representation and the affordances of digital technology. To a great extent, photographs in the collection were produced as personal mementos or, in the case of studio portraits, were not necessarily meant to be circulated widely. AIF members are invested in developing modes of presentation and display that honor the original private nature of the photos while acknowledging their significance as cultural artifacts.

One consequence of this transfer of private photographs to an institutional public context is that the AIF and its members have felt obliged to negotiate continuously between the respectful handling of affective objects and the responsibilities that come with the preservation of cultural heritage as a common good. The widespread dissemination of images made possible through digitization has raised questions about how to deal with private and personal images (for example, portraits and snapshots that might still be linked to living people or their relatives) and the stakes of unconstrained public access. In fact, the AIF is currently in the process of revising many of the original contracts for deposits of family collections and photography studios. Although these collections were acquired under specific contractual agreements, the updated contracts will ensure depositors only grant access to their photos under conditions they still feel comfortable with. Another question that has become exceedingly important for the collecting practice of the AIF today is the extent to which it is necessary to focus on the preservation of material objects, or whether it would in some cases be sufficient or even preferable to collect only digital reproductions.

Of all the AIF members, Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh and Akram Zaatari have been particularly committed to addressing the implication of the transfer of photographs from private contexts to the foundation’s collection. Within their artistic practices they have highlighted the significance of photographs as transgenerational links, as well as the importance of preserving images alongside the stories surrounding them.

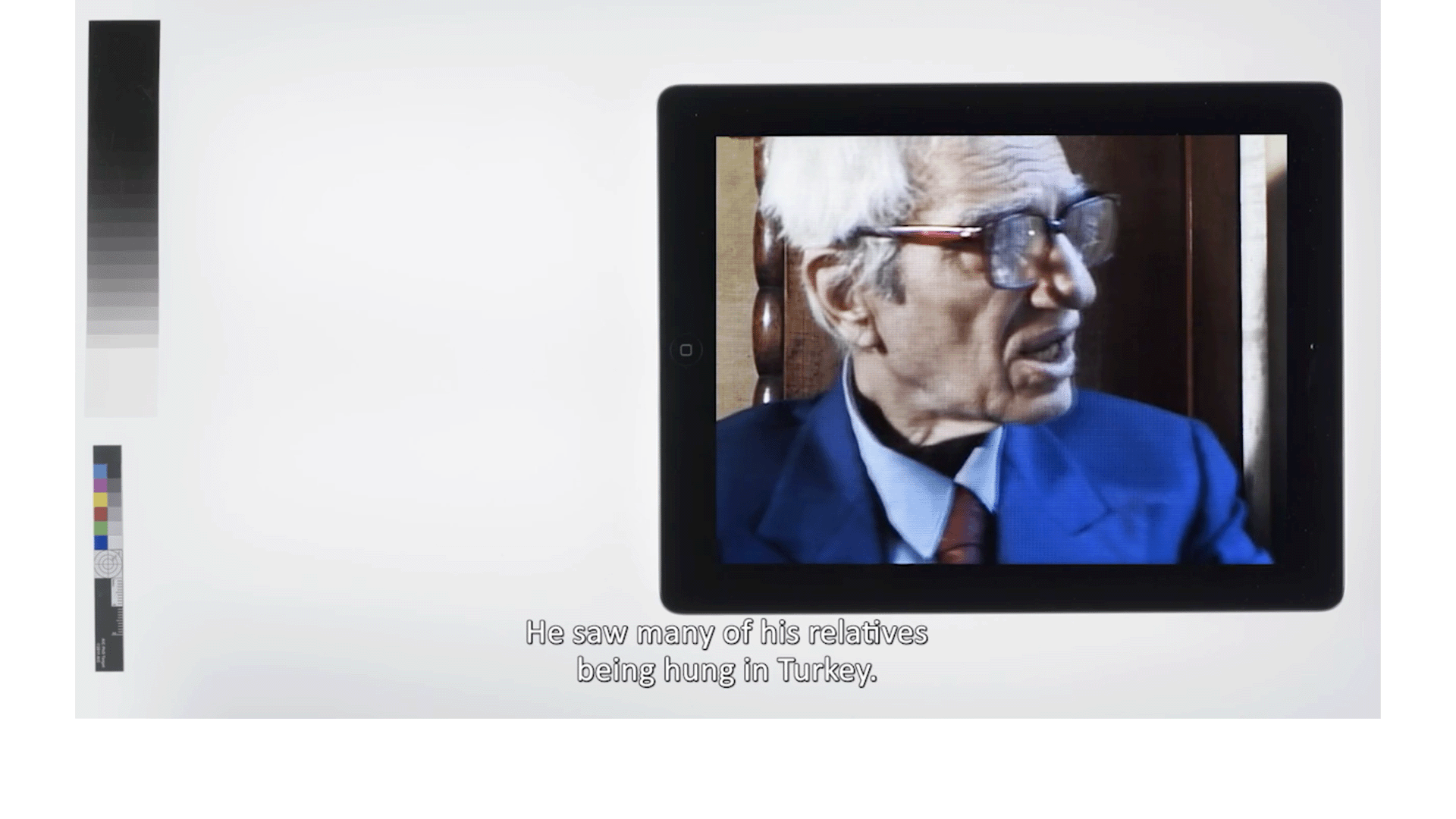

Take Zaatari’s video On Photography, Dispossession and Times of Struggle (2017), which considers the personal dimension of photographs in relation to their relevance as historical documents. A series of photographs are displayed on a light table next to a person wearing blue archival gloves. Beside the photographs, iPhones and iPads show videos of the pictures’ original owners, who discuss their photos, the events captured within them, and the political turmoil they and their families went through. In one scene, Van Leo talks about the Armenian genocide, describing his parents’ exodus from Turkey to Egypt. He’s followed by Samia Mahmoud, who shares her memories of the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948 and how she and her family were expelled from their home in Ramla. She didn’t have the chance to take her photographs with her, she explains. They were later found scattered on the street after the Zionist military organization Haganah seized control of the region.

Zaatari’s video juxtaposes photographs as cherished mementos and as objects that have become part of an archive. The video highlights the material characteristics of photographs as well as their affective potential. Presenting photographs together with oral accounts, Zaatari negotiates their meaning in a broader political context and in relation to historical events that the images themselves don’t necessarily depict. In combination with the memories and the eyewitness accounts of their original owners, the pictures are meant to convey individual fates embedded in a grander schematization of history in order to “create” more witnesses to injustices that are rooted in the past but persist in the present.

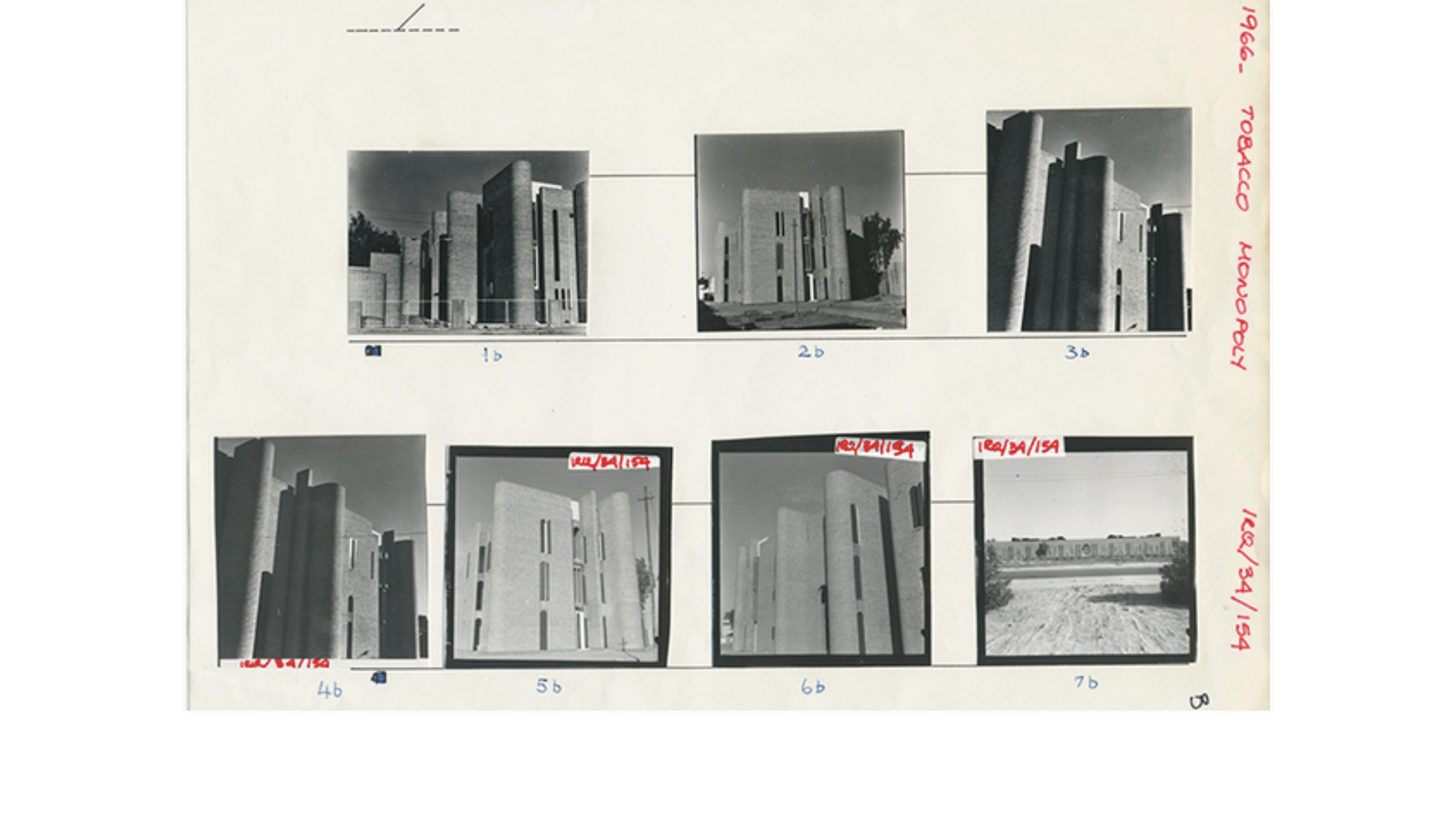

Trailer for TWENTY-EIGHT NIGHTS AND A POEM (Akram Zaatari, 2015).

While On Photography, Dispossession and Times of Struggle frames old photographic prints and negatives next to analog video recordings displayed on digital screens, the work also showcases Zaatari’s interest in the evolution of visual media and the impact of different image technologies on different generations. This form of media archaeology and reflection on the concept of media generation is even more extensively exercised in his feature-length film Twenty-Eight Nights and a Poem (2015), on the Lebanese photographer Hashem El Madani.

Madani ran Studio Shehrazade in Sidon, the capital of South Lebanon, from 1953 until shortly before his death in 2017. Zaatari, who himself grew up in the city, had already visited Madani’s studio as a child. He became better acquainted with the photographer, who claimed to have taken portraits of 90 percent of Sidon’s population, while conducting research for the AIF exhibition The Vehicle (1999). Shortly afterward, Madani gradually handed over his entire archive of negatives and prints to the foundation. Zaatari, in turn, began his still ongoing project Objects of Study: The Archive of Studio Shehrazade.

Twenty-Eight Nights and a Poem consists mostly of scenes that show Madani in his studio discussing different aspects of his career. He explains which poses he preferred for women and for men. He mentions how he used to go to the beach and to Sidon’s corniche in order to take pictures of swimmers and passersby, who could afterward purchase their photos at his studio. In one scene, Madani refers to portraits of young men that wanted to be photographed with guns at the beginning of the Lebanese Civil War. In another, he tells Zaatari about a woman who urged Madani to capture her in the nude.

Apart from portraying Madani and his life’s work, Twenty-Eight Nights and a Poem provides an overview of the transformation of media and technology the photographer encountered beginning in the 1950s. This not only involves the evolution of photography from a laborious mechanical-chemical process to the relatively effortless capture of a smartphone’s digital button. Twenty-Eight Nights also chronicles the development of different film, video, audio, and digital technologies. Throughout the film Zaatari can repeatedly be seen typing something into a search engine, gesturing to the idea of the internet as a universal archive. The individual scenes of Twenty-Eight Nights are introduced by short texts that define media terms or equipment, from “photo studio” to “YouTube” to “Bluetooth,” while shots of iPhones, iPads, and laptops recur. As in On Photography, Dispossession and Times of Struggle, these devices generate a series of images within images through their displays of film excerpts, TV snippets, and YouTube clips.

TWENTY-EIGHT NIGHTS AND A POEM (Akram Zaatari, 2015).

While On Photography, Dispossession and Times of Struggle is characterized by sober and restrained aesthetics, Twenty-Eight Nights and a Poem is more sentimental in tone. Zaatari pays tribute to Madani and their friendship. Furthermore, he raises questions about what exactly gets preserved when we hold on to physical records of the past. Those records are not only testimonies of events—the too-rigid focus of many preservation practices—but also tokens of personal relationships and experience. Acknowledging the essentially transitional nature of all things, Zaatari’s ideal form of preservation is an emphatic caregiving that values photographs not only as historical documents but as affective objects. Thus, preservation is not enough; it’s also necessary to activate through contextualization and remediation. For Zaatari this is the only way the affective object/historical document can continuously unfold meaning, that it can have second or multiple lives.

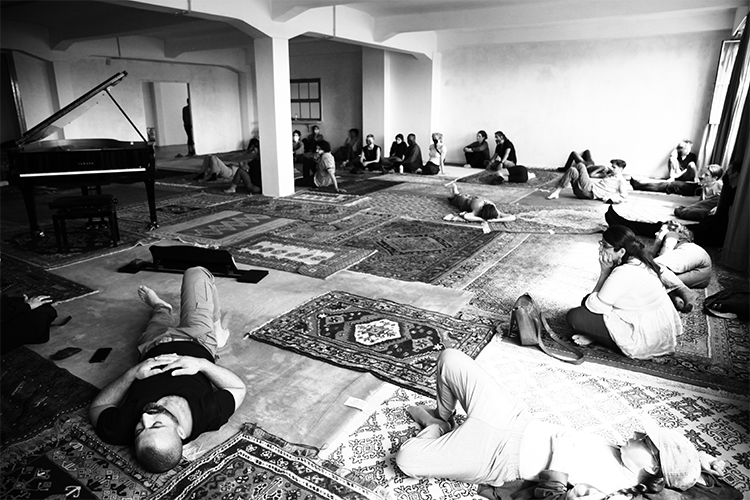

The question of activation—in particular the relationship between personal affect, memory, and history—is also at the core of Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh’s Frictional Conversations, a project she started in 2001 and presented most recently during documenta fifteen in 2022.{5} Burj al-Shamali is a Palestinian refugee camp that was established southeast of the city of Tyre after the Arab-Israeli war in 1948, accommodating thousands of refugees forced to flee Palestine following the creation of the State of Israel, referred to by Palestinians as the Nakba. Eid-Sabbagh’s Frictional Conversations combines archival, historiographic, ethnographic, performative, and collective practices to look at the history of the camp and how four generations of its inhabitants have been affected by the consequences of the Nakba. In the context of her project, Eid-Sabbagh collected thousands of studio and family photographs from 1947 to 1990 and collaborated with a group of adolescents in workshops and exhibitions in order to shed light on the role of photography in forming collective and individual identity in the camp.

Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh, FRICTIONAL CONVERSATIONS: SONIC MATERIALIZATIONS, documenta fifteen, June 2022. Courtesy of Ahmad al-Khalil.

Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh, FRICTIONAL CONVERSATIONS: SONIC MATERIALIZATIONS, documenta fifteen, June 2022. Courtesy of Ahmad al-Khalil.

The AIF supported Eid-Sabbagh’s project financially starting in 2007, and she became a member in 2008. Despite the foundation’s initial aim to preserve prints, negatives, glass plates, and albums, Eid-Sabbagh only collects digital surrogates. For her, photographs are not only, or even primarily, “physical objects” but rather “multi-layered substances” that consist of what she calls several “meta-medial layers”: the “narratives,” “affects,” and “positions”—in short, all the subjectivities, experiences, and politics that surround or overlay and can even produce a photograph’s embodied material strata. According to Eid-Sabbagh, this understanding of photography “puts the people concerned, the people who took and collected the pictures, at the center. . . . Photographs, as multi-layered substances, composed of a stratified physical object with different layers (i.e. paper, emulsion, etc.) and other forms of layers that make up the image of the photograph (i.e. audio recordings of story-telling, conversations or silence, usage permissions, textual descriptions or narratives), thus become moments of awareness.”{6}

In line with this concept of the photographic image, Eid-Sabbagh’s priority is not to make the digital reproductions she collects accessible to the public. During her interventions or performances within the Frictional Conversations project, she seeks to activate the “meta-medial layers” that constitute photography differently. Instead of showing her audiences photographs, she structures her performances mostly around conversations and interviews with Burj al-Shamali’s residents. Using video and audio recordings, Eid-Sabbagh addresses different attitudes toward photography in general as well as people’s relationship to specific images. During this process, she observed that an older, more conservative generation in the camp considers photography and its realism partially problematic, as it stands in conflict with the aniconism of Islam. Consequently, according to Eid-Sabbagh, there are rarely any photos on display in homes, unless they portray deceased relatives. By contrast, the younger generation, especially those who grew up with digital technology and the internet, regard photography as an important tool for communication and self-expression.

In the context of her project, Eid-Sabbagh has also been handed images for the purpose of informing the public about the hardship of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. Although Eid-Sabbagh mentions those details in her performances and interventions, she tries to ensure that the photos in her collection are neither turned into a spectacle nor instrumentalized ideologically. With this “refusal to represent,” as Denise Ferreira da Silva puts it, Eid-Sabbagh creates a tension that consciously differentiates between her own position, that of her interlocutors, and that of the audience.{7} This also applies to the way she plans to integrate some of the images from her Burj al-Shamali collection into the AIF database. They have not been cataloged and documented according to the foundation’s reference system and will only be viewable at specific times. For example, the ID photograph of a camp inhabitant who was killed during an Israeli air strike on July 13, 1978, will be visible only on July 13 every year. Her interventions intend to maintain the Burj al-Shamali collection as “a space of ongoing conversation and negotiation.”{8} Digitization and public access “allow for a complex and collective voice to appear, in which individual positions can exist and contribute to a collective aim/claim . . . that transcends the habitual limitations of time, space and origin/identity, and which allows for new and multiple modes of engagement.”{9}

This form of collective activation—which also stands in relation to the AIF collection at large—is meant to be achieved through a complex remodeling of the foundation’s image database and the development of the current AIF online platform. The online platform is not only a virtual gateway that provides “universal access” to parts of its collection. Serving mainly as a research tool, it’s also the foundation’s display window, presenting the achievements of its members and their artistic research to a wider public.

In 2002 the foundation launched its first website, and two years later its first online image database. By 2009, after several updates, around 20,000 photographs from the collection could be accessed online. Then, in 2016, the foundation intensified its digitization efforts. At the same time, the AIF began to revisit its scanning and reproduction policies, which went hand in hand with the development of its current online platform. The platform’s beta version was launched in May 2019, and while it’s still a work in progress, it already provides access to about 28,000 images.

The old database presented photographs primarily as pictures in the same format, adapted to a uniform grayscale or coherent color spectrum. These reproductions, however, were scans of photographic prints, glass plates, or negatives of various kinds, formats, and sizes. Details that are visible in the originals, the haptic qualities of the image carriers—that is, their material characteristics, signs of aging, usage, and, in some cases, traces of damage—were difficult to perceive or even undetectable in these small, low-resolution image files and thumbnails.

The current platform makes the specific characteristics of each digitized photographic object visible. It emphasizes material qualities by presenting several scans of each photograph, including recto and verso scans to show both the image and any personal notes or description on the back of it. In some cases, negatives are displayed alongside their photopositives. Compared to the old database, the new interface imbeds images in a more dynamic, synergistic setting that aims to generate interaction and conversations besides facilitating individual research.

Screenshot, AIF platform.

Screenshot, AIF platform.

For now, the platform provides regular updates about the current activities of the AIF, such as a February 2022 talk with the editor in chief of Cold Cuts, Mohamad Abdouni, on the documentation and archiving of trans* narratives and histories in Beirut; and a workshop held by Vartan Avakian, Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh, and Kristine Khouri on “Rights, Materialities and Photographic Agency” at New York University’s Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies in spring 2021. The platform also provides links to podcasts in which the AIF highlights and discusses specific parts of its collection.

Furthermore, the platform feature LAB is conceived as “a digital outpost for forays into uncharted spaces of photography.” LAB is meant to be a “catalyst for new forms, ideas, and discussions” that invite artists, writers, thinkers, researchers, coders, engineers, and filmmakers for “creative interactions” that “merge imaginative thinking and transdisciplinary experimentation, journeying to the shifting horizons of photography and archiving.” One example is an essay by historian Vahé Tachjian on the photographs of the Near East Foundation, an organization that was engaged in wide-ranging religious and humanitarian work in the Ottoman Empire, focusing on the provision of aid to Armenian refugees and orphans.{10}

The objective of the platform is eventually to open up the processes of annotation, categorization, and attribution. The AIF is planning to implement more features so that visitors can directly interact with the foundation and contribute to documenting individual images through a tagging tool. Consequently, digitizing and remote access gradually become a means of decentralization. Through sharing the documentation process with users of the platform, as well as extending an open invitation to activate parts of its collection through collaborations and interventions, the foundation takes a deliberate stance against the authoritarianism of expert culture. The distribution of agency resonates with Barthes’s notion of photography as a shared skin, the membrane of community and co-responsibility.

At the same time, decentralization is also facilitated through digitization in the sense that at least some “meta-medial layers” of the photographs in the AIF collection are not physically bound to one place. This aspect became particularly important after the catastrophe of August 4, 2020, which caused the AIF to consider new safety options. As a first measure the AIF moved its networked storage devices and offsite backups to different locations. But its members also began considering more drastic actions, such as the diffusion of the foundation’s physical archive. As Vartan Avakian put it, “The collection is from the Arab world, so it’s in diaspora already. . . . There’s always been a need for us to have some kind of place in North Africa, in the Gulf, in Sham, other places.” However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the AIF will leave Lebanon altogether. According to Avakian, it could “have different existences, sometimes in collaboration with other institutions.”{11}

A kind of diasporic existence could potentially enrich the foundation’s collection through a more widespread production of documents. Transgenerational links materialized in photographs would be further connected to a diasporic agenda, promoting the continued transmission of memory and a critical examination of colonial legacies based on a shared interest in photography and its history. “The exile,” Edward Said writes, “knows that in a secular and contingent world, homes are always provisional. . . . Orders and barriers, which enclose us within the safety of familiar territory, can also become prisons, and are often defended beyond reason or necessity. Exiles cross borders, break barriers of thought and experience.”{12} Avakian’s considerations to disperse the foundation’s collection resonate with this celebration of exile and its potential.

When and if the dispersion of the AIF collection will actually happen is unclear. For now, it seems that the collection will remain in Beirut. In January 2023 the AIF announced its move to a new space in the Kantari district that “will accommodate improved preservation and digitisation labs; a larger cool storage room and a quarantine area for incoming collections; a work and display area; and a new space dedicated to library resources and to welcoming researchers.”{13}

However, the idea to “exile” the collection makes evident the limits and challenges the foundation’s members have been facing in regard to preservation and representation over the past twenty-five years. It shows once again that in order to safekeep cultural heritage sustainably it is imperative to constantly activate it. Besides protecting this heritage from deterioration and damage, what matters most, now maybe more than ever, is to keep a discourse around it in motion. A discourse that involves different generations to ensure that the foundation and its collection will have many future lives, or in Avakian’s words, “different existences.”

Title video: Twenty-Eight Nights and a Poem (Akram Zaatari, 2015).

{1} Geoffrey Batchen, “Vernacular Photographies,” History of Photography 24, no. 3 (2000): 262. In relation to the situation in the Middle East, see also Lucie Ryzova, “Mourning the Archive: Middle Eastern Photographic Heritage between Neoliberalism and Digital Reproduction,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 56, no. 4 (October 2014): 1027–61.

{2} See Pierre Bourdieu et al., Photography: A Middle-Brow Art, trans. Shaun Whiteside (Cambridge: Polity, 1990).

{3} Apart from these projects developed around the AIF collection and the individual research of different members, the foundation over time has also become an advisor for numerous photo archives and collections in the Middle East, with the Middle East Photography Preservation Initiative (MEPPI) serving as a cornerstone. Launched in 2009 in collaboration with the University of Delaware, the Metropolitan Museum, and the Getty Conservation Institute to identify and assess significant photograph holdings across the Arab world, Turkey, and Iran, the project includes a series of courses and workshops to train personnel responsible for the care of photographic collections in the region. Another major initiative to create an institutional network to promote cultural heritage in the Middle East and North Africa is the Modern Heritage Observatory (MoHO), founded by the AIF in 2012 together with the Association for Arabic Music, the Arab Center for Architecture (ACA), and the Cinémathèque de Tanger.

{4} Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 2010), 81. In a similar vein, for Marianne Hirsch photography grants the power to transmit experiences from one generation to the next “so deeply and affectively” that the conveyed events consequently become “memories in their own right” for later generations, in a form she calls “postmemory.” Marianne Hirsch, “The Generation of Postmemory,” Poetics Today 29, no. 1 (Spring 2008): 106.

{5} The initial title of the project was A Photographic Conversation from Burj al-Shamali Camp. Eid-Sabbagh refers to it as an “ongoing or recurrent negotiation” instead of explicitly using the term activation.

{6} Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh, “Extending Photography: The Meta-Medial/Conversational Layers of Dematerialized Photographs,” Photography & Culture 12, no. 3 (July 2019): 309.

{7} Denise Ferreira da Silva, “Reading Art as Confrontation,” e-flux Journal, no. 65 (May 2015).

{8} Eid-Sabbagh, “Extending Photography,” 315.

{9} Eid-Sabbagh, 318.

{10} Vahé Tachjian, “The Near East Foundation’s Collection of Photographs of Armenian Farming Settlements in Syria,” trans. Simon Beugekian, Houshamadyan (link provided on Arab Image Foundation platform, issue #2021.04), April 4, 2021.

{11} Vartan Avakian quoted in “Luckily This Art Collection Went Unscathed Despite the Beirut Explosion,” Al Bawaba, August 27, 2020.

{12} Edward Said, “Reflections on Exile,” in Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 147.

{13} “AIF relocates to Kantari and hosts Dawawine in its new space,” Arab Image Foundation, issue #2023.01, accessed March 19, 2023.