Just Evidence

Sasha Crawford-Holland, Patrick Brian Smith, and LaCharles Ward

Patrick Brian Smith is an assistant professor and university fellow in the School of Arts, Media and Creative Technology at the University of Salford. His research addresses how evidence is mediated, and critically explores the associated opportunities for both harm and repair. His book Spatial Violence and the Documentary Image was published in 2024.

LaCharles Ward is a scholar, curator, and writer whose research and curatorial work centers on photography, time-based media, and black studies. His current research rethinks the grounds of evidence—as a concept, question, and practice—by drawing on black studies, the history of photography, and the law. This work has appeared in History of Photography and Black Camera.

The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.

—Audre Lorde

If the master loses control of the means of production, he is no longer the master.

—Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Public Enemies and Private Intellectuals: Apartheid USA”

What does accountability look like? For at least the past fifteen years, the answer has been overwhelmingly forensic. Artists and activists working to hold power to account continue to take up the tools of the state to furnish proof of its violence. These technoscientific tools—of documentation and surveillance, digital identification and verification, data mining and analysis, remote sensing, mapping, and modeling—seem to guarantee bulletproof evidence. They promise authority, legibility, and access to legal-accountability mechanisms that would otherwise remain out of reach for the socially and politically marginalized. Amid the anxieties of the post-truth era, professionals and publics are reinvesting faith in the old idea that lens-based technologies can assert facts that can be leveraged in pursuit of justice.{1} While some appropriations of these tools explicitly identify themselves as forensic, their ways of sensing and thinking have come to pervade contemporary media ecologies more broadly, especially as consumer technologies democratize access to the means of evidentiary production. Cellphone videos of police brutality, secret recordings of corporate environmental violations, digital reconstructions of war crimes, and metadata scraped from dating apps to reveal clandestine military operations all exploit media’s evidentiary capacities to hold power to account. From true-crime podcasts to art exhibitions, from news outlets to film festivals, contemporary media cultures are awash with forensic evidence of violence.

More recently, social movements working toward abolition and decolonization have surged to public prominence. Documentary recordings of state violence have catalyzed mass uprisings for racial justice that challenge popular views of policing and criminal punishment as bastions of justice, transforming political imaginaries in their wake. That demands such as “defund the police” have entered mainstream vernaculars is remarkable. Almost as remarkable is the conjuncture of these two movements: toward technological proof adjudicated in courts and toward liberation from punitive systems. At first glance, social movements that regard the state as a source of harm (not justice) appear diametrically opposed to projects that adopt the state’s juridical methods. Put differently, forensics and abolition may seem to be fundamentally incompatible. The former defines accountability primarily as a procedural outcome of criminal justice; the latter works to build institutions that address harm without relying on the state and its courts. Yet, for many on the ground, these relations aren’t so clear-cut.

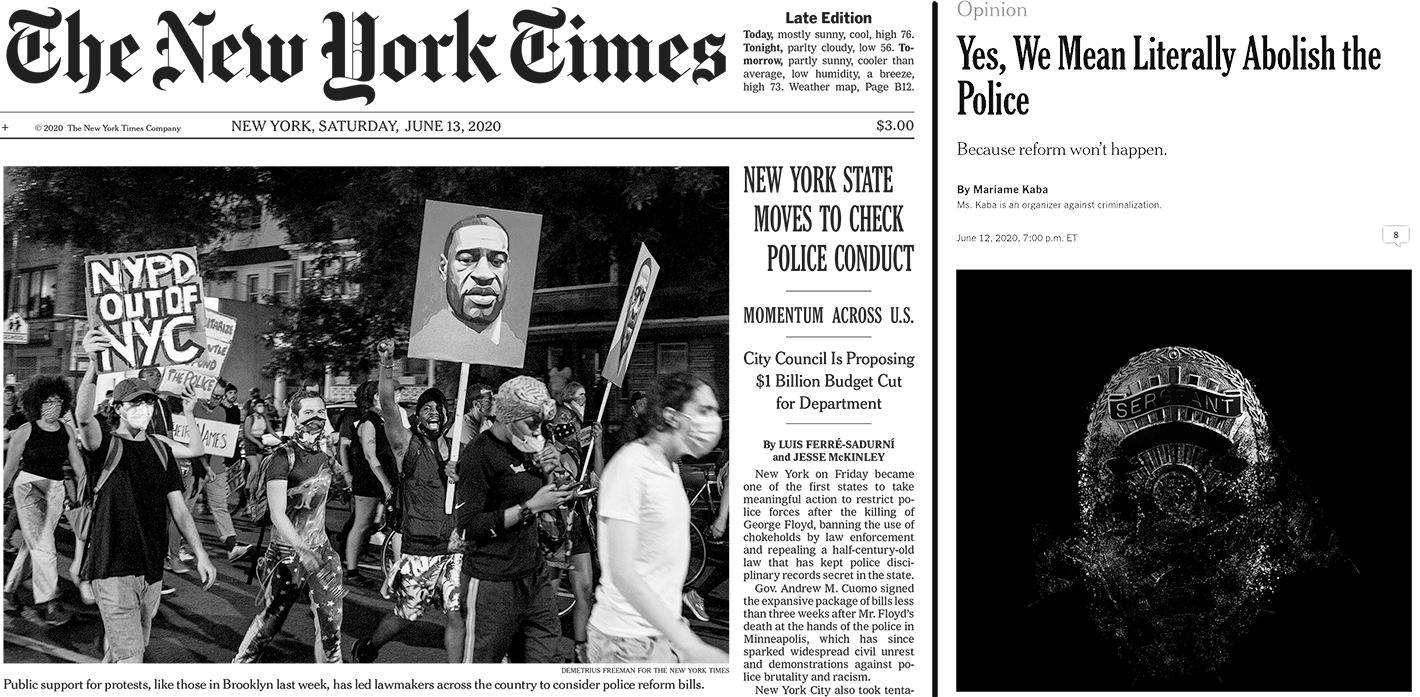

Left: NEW YORK TIMES front page, June 13, 2020. Right: "Yes, We Mean Literally Abolish the Police," by Mariame Kaba, NEW YORK TIMES, Sunday Opinion, June 12, 2020.

Left: NEW YORK TIMES front page, June 13, 2020. Right: "Yes, We Mean Literally Abolish the Police," by Mariame Kaba, NEW YORK TIMES, Sunday Opinion, June 12, 2020.

Consider the prominence of “true crime,” one of the most popular entertainment genres in contemporary US culture.{2} Its use of nonfiction media to investigate criminal cases epitomizes forensics’ expansion from a specialized profession into a wellspring of popular culture. Some of these films, TV series, and podcasts aim to challenge the inequities that structure the criminal legal system. An entire subgenre has emerged dedicated to exposing wrongful convictions, which has resulted (in rare cases) in people being exonerated and released from prison. This subgenre combines nonfiction media’s evidentiary tools with the moral pathos of subjects overcoming injustice, while authenticating documentary’s often elusive promise not just to interpret the world, but—echoing Marx’s famous call to action—to change it.{3} This subgenre might be regarded as abolitionist insofar as it is nominally invested in decarceration. Yet its critiques of the system can subtly reinforce that system’s foundations. By meticulously verifying supposedly objective designations such as innocence and guilt, true crime presents crime as the truth—and not an invention of the state. From an abolitionist perspective, all convictions are wrongful because they perpetuate a system that is rooted in structural inequality and violence. As Pooja Rangan and Brett Story have argued, documentaries that locate the truth in carceral categories reify the construct of crime and justify the violence done in its name.{4}

This dilemma lies at the heart of forensic practices that appropriate the state’s tools to mitigate its violence. When the powerful deny, obfuscate, and fabricate facts, documentary evidence suggests that truth can be seen, measured, proven—and that proof will lead to accountability and justice. But, in their pursuit of accountability, forensic practices often draw authority from the very institutions they seek to challenge: the law, the police, the colonial state, the tech oligarchy. They bring renewed urgency to an old conundrum: Can the master’s tools dismantle the master’s house? Can technologies of prosecution and incrimination work against state and corporate power? How can evidentiary practices chart trajectories toward abolitionist and decolonial horizons?

For the activists whose work is taken up in this volume, these questions are more strategic than moral. People working to liberate themselves and others from captivity often have no alternative but to deploy narratives of innocence or technologies of exculpation—however compromised these tactics and tools may be—as their only way out. It’s hard to reject the system when you’re in one of its cages. Métis scientist Max Liboiron, who works at the intersection of environmental science and anticolonial research methodologies, confronts similar dilemmas while conducting anticolonial science in the context of dominant science. As they reflect, “Compromise is not about being caught with your pants down, and it is not a mistake or a failure—it is the condition for activism in a fucked-up field. Research and activism, scientific or otherwise, never happen on a blank slate.”{5} For example, for Liboiron to produce knowledge about colonial pollution, they may need to employ tools and methods that, themselves, contribute to pollution. There is no position of purity outside of that dilemma because the world has already been polluted. The fields in which scientists, activists, and artists maneuver are already conditioned by the histories of power against which they intervene.

As the fields grow ever more fucked up, this volume of World Records explores how artists and activists are navigating the terrain. We center the complexities and contradictions involved in the hard work of media activism, studying how they ramify across multiple registers: the technologies used to create evidence; the aesthetic and epistemological practices through which we make sense of it; the institutions that assemble publics to interpret its significance; and the cultural narratives that underwrite them all. We foreground these practices’ ambivalent promise under the multivalent rubric of just evidence. On one hand, this phrase signals evidence’s enduring, and perhaps even renewed, capacity to provide access to standing, legibility, and accountability. It expresses a faith in evidence—a belief that truth is on the side of justice. On the other hand, just evidence underscores evidence’s perpetual ambiguity and inadequacy. Absent enforcement mechanisms, institutional power, or political momentum, what we are left with is precisely that: just evidence.

****

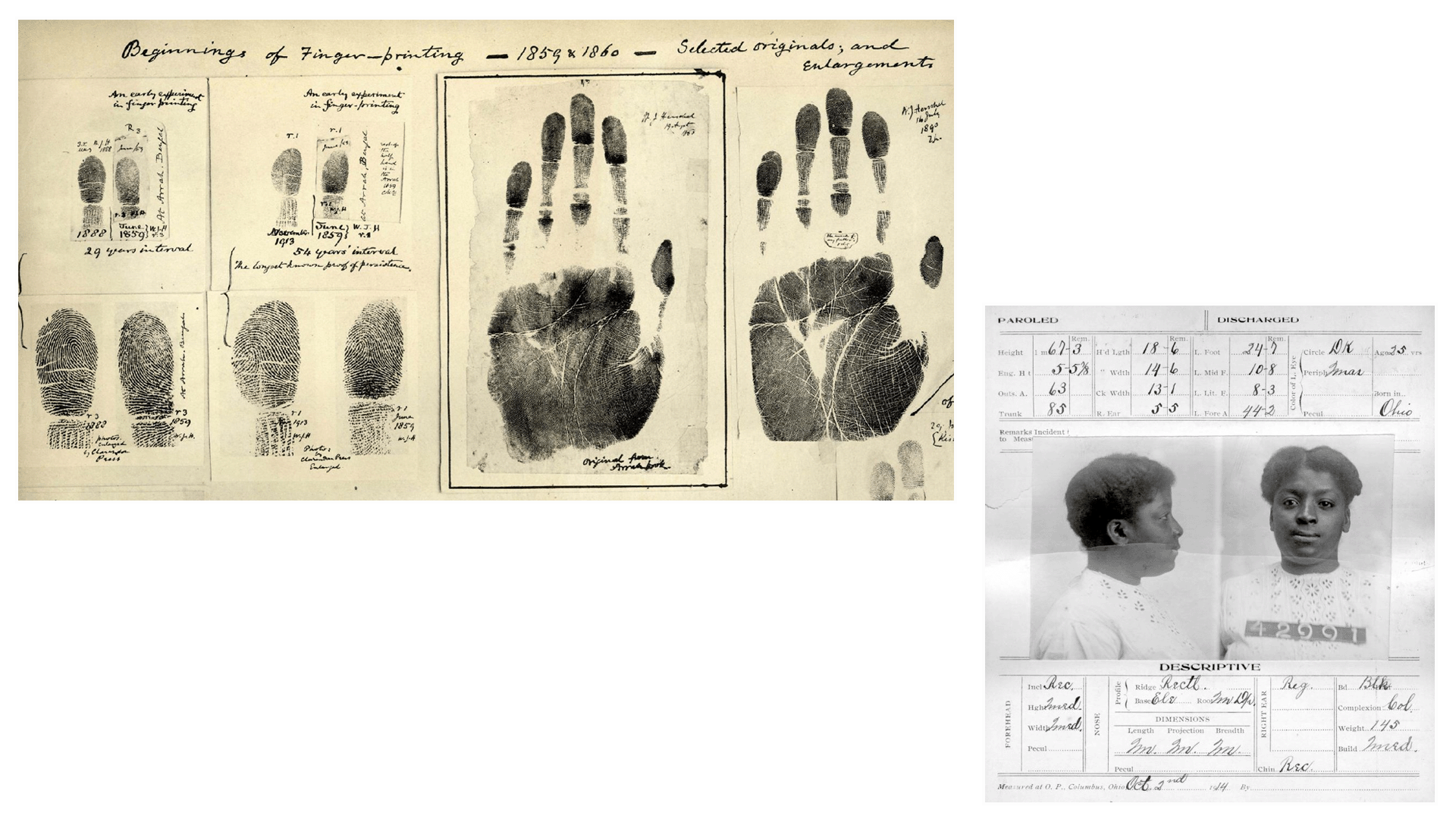

The range of practices identified as forensic aim to produce legible proof—through visual, auditory, chemical, textual, and other material traces—of that which is otherwise occluded. When practitioners mobilize forensic media to assert truth claims, they endow representations with the status of empirical evidence. Forensics emerged as a technoscientific and criminological epistemology in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as advances in medicine and science were increasingly applied to criminal investigations. For example, in early 1800s Spain, chemist Mathieu Orfila came to be known as the “father of toxicology,” pioneering the use of chemical analysis to detect poisons in bodily fluids. In late 1800s France, police officer and biometrician Alphonse Bertillon began applying the practice of anthropometry to criminal investigations, creating the first scientific system used by police forces to identify criminals based on physical measurements. Fingerprinting was introduced by British colonists in 1800s India as a tool for social control. As these practices became institutionalized, they “lent epistemic authority to law enforcement, buttressing a moral and juridical paradigm that attributed criminal acts to individual culprits, not social conditions.”{6} Modern forensics not only facilitated but legitimized the expansion of racist, punitive, and surveillant state power.

Technological developments have expanded forensics’ reach. Genetic sequencing, geolocation analysis, AI-driven pattern recognition, and social media monitoring are only some of the techniques that have augmented institutions’ capacities to track, categorize, and control populations with unprecedented precision. The scientific provenance of many forensic methods lends an authoritative sheen to their promises of security, efficiency, and predictive governance. While they may masquerade as empirical technologies that merely describe, they actively shape the world. They present policing as a seemingly objective, scientific enterprise while expanding the reach of the carceral system. Their methods can even abet necropolitical violence. For example, the regimes of surveillance and control that have been developed over decades to maintain Israel’s settler-colonial stranglehold over Palestinians have now become tools of genocide.{7}

At the same time, the increased availability of consumer and open-access technology has democratized forensic methods that were once the exclusive purview of the state and private enterprise. The master, to rephrase Gilmore, has lost some control of the means of evidentiary production. Activists have appropriated them to innovate counterforensic practices that “deploy scientific investigative techniques usually wielded by the state against the state.”{8} Counterforensics strategically subverts forensics against its own internal logics to create “an archive of accountability and resistance against the very same formations of power responsible for generating them.”{9} Practitioners leverage techniques such as audio spectral analysis, cartographic regression, photogrammetry, 3D modeling, situated testimony, and remote sensing to push back against state-corporate control over the production of evidence. Working across media forms, those developing counterforensic methods have been united by a desire to employ documentary media as tools for accountability. Their methods “challenge the state’s monopoly on the production and analysis of evidence, approaching archives of violence as terrains of epistemic struggle, not self-evident meaning.”{10} Forensics becomes a domain of “interpretive dispute,” not conclusive verdicts.{11} As Thomas Keenan notes, these disputes are animated by counterforensics’ “non-naive commitment” to the truth—not to relativism, but to setting the record straight.{12} The diverse practices that we assemble under the umbrella of just evidence reflect a range of non-naive commitments to this elusive notion. While some leverage technologies of mechanical objectivity to corroborate the truth of systemic violence, others insist on the primacy of social or sensory knowledge as the truths from which to build a better world.

Practitioners of counterforensics must navigate strategic complexities as professionals working in alliance with grassroots activists from compromised positions in human rights agencies, news outlets, media production companies, or other institutions whose objectives are not always aligned with those of social movements. For example, the democratization of access to the state’s evidentiary tools has also meant the democratization of its ways of assessing and addressing harm. Rangan observes that “over the last thirty years, appeals to documentary audiences as arbiters of public truth have overwhelmingly been couched in terms of the democratization of the authority to adjudicate and sanction human rights violations by malign state, military, and corporate actors on the basis of evidentiary claims.”{13} Audiovisual media that acculturate audiences to “seeing and listening like a state” respond to abuses of power by criminalizing the powerful. They work in uneasy tension with abolitionist principles as they simultaneously subvert and claim carceral authority—an ambivalence encapsulated in the activist indictment that “the whole damn system is guilty as hell.”

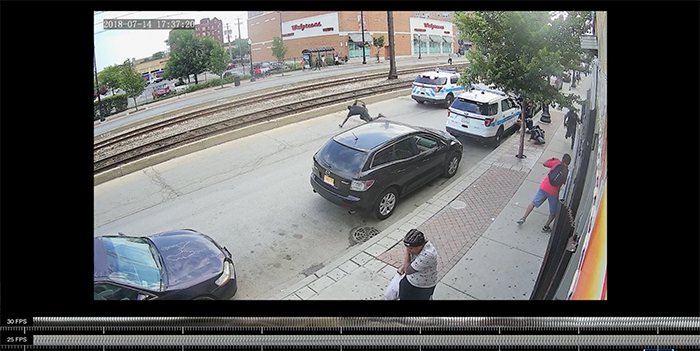

"The Killing of Harith Augustus," investigation led by Forensic Architecture Lab in collaboration with Invisible Institute, Architectural Association (2019).

"The Killing of Harith Augustus," investigation led by Forensic Architecture Lab in collaboration with Invisible Institute, Architectural Association (2019).

The digital democratization of evidence may suggest a recent development, yet counterforensic methodologies are rooted in deep, often overlooked histories of struggle and witnessing that have long negotiated ambivalent relationships to documentary media. For example, during the 1965 civil rights marches in Selma and Montgomery, Alabama, the Alabama Department of Public Safety took surveillance photographs of protests for the purpose of intimidation and visual documentation that could later serve as evidence for prosecution. They also hired a team of documentary filmmakers to record dramatic surveillance footage, which was later used in the racist and anti-black propaganda film produced by the Alabama State Sovereignty Commission.{14} These activities were intended neither for news coverage nor for historical recordkeeping, but to serve as evidence of the need to further suppress the marchers and their fights for freedom. Simultaneously, though, images of the same events served to galvanize popular support for civil rights. Photographic imagery of state violence against demonstrators printed in newspapers and broadcast on television visualized the very conditions against which the marches had been organized. The images of demonstrations, as Leigh Raiford has argued, “appeared as tableau vivant of an entire economic and social regime of power.”{15} Activists appropriated the very tools of surveillance to challenge its material impacts and, moreover, to reveal how people are differentially subjected to carceral power. In Marking Time, Nicole Fleetwood describes how incarcerated artists develop such “clandestine practices” to “create art under the conditions of scarcity of resources, lack of control of one’s environment, immobility, constant surveillance.” These practices offer a glimpse into carceral surveillance, but also show how the incarcerated create new social relations and thwart, in a minor key, “written and unwritten prison codes.”{16}

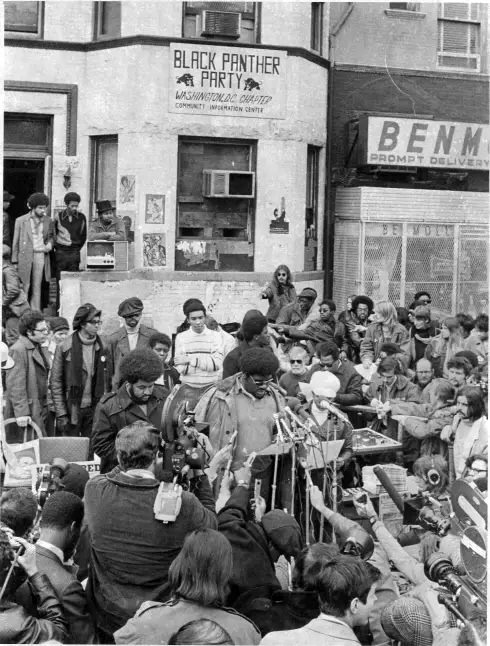

Addressing the news media in response to police violence in Alabama, Martin Luther King Jr. declared “to the white men that we no longer will let them use clubs on us in the dark corners. We’re going to make them do it in the glaring light of television.”{17} King’s keen attunement to the glare of documentary technologies informed his advocacy of a strategy of nonviolent resistance—one that produced counterforensic visual documentation of white tyranny in the face of black civility to substantiate the movement’s moral narrative. Others were skeptical of such strategies, which relied on images of black passivity that ironically cast white violence as the agent of social progress. Yet they too leveraged counterforensic tools to generate evidence in support of justice. Whereas King tactically navigated the “light of television,” others have opted for strategies of what Simone Browne terms “dark sousveillance,” concealing themselves from surveillance’s glare while appropriating tools of social control—fashioned on the plantation but extending beyond it—to facilitate escape.{18} The Black Panther Party, for example, understood the multifaceted ways in which they were surveilled but also developed their own strategies for producing evidentiary media. While the Panthers questioned King’s reliance on media to cultivate white sympathy, they sought to appropriate the master’s evidentiary tools “for antiracist and anticapitalist goals.”{19} More fundamentally, the Panthers’ intention was to “establish a visible presence in black communities, to produce new knowledge about the capacity of black people to control black communities, and to announce an alternative model of political action by putting those actions on ostentatious display.”{20} They recognized that the very technologies of documentation designed to globalize Western empire had also opened channels through which critiques could be shared and anticolonial solidarities could be forged. The master had lost control of the means of media distribution.

Elbert Howard of the Black Panther Party holds a press conference in Washington, DC, 1970. Photograph by Stephen Shames.

Elbert Howard of the Black Panther Party holds a press conference in Washington, DC, 1970. Photograph by Stephen Shames.

(Counter)forensic methods of producing just evidence have proved useful for communities attempting to narrate their own truths, articulate their own conceptions of evidence, and craft a forensic that is not simply objective, but also performative and affective. Still, persistent streams of imagery documenting racist and genocidal violence have rarely delivered the accountability we might wish them to. For many in black and brown communities, while there seems to be a preponderance of visual evidence to indict policing institutions, when such evidence is placed under the forensic microscope, when it fails to meet juridical thresholds of proof, the promise of documentary evidence falters too. If evidence is a tool, how can it be leveraged? What else is required—what social and aesthetic infrastructures do we need—to make it work?

****

Despite widespread recognition of evidence’s instability, publics continue to invest faith in the promise of documentary proof. Counterforensics can support activism precisely because it provides tools for contesting dominant interpretations and advancing alternatives. Evidence is not found; it must be made, championed, and defended. But even with interpretive resources on our side, mistaking evidence for salvation assumes that more evidence leads to more accountability. Ironically, though, evidence has never been more abundant than it is today. We live in a world of information overload, not deficit. In many cases, as Yasmina Price writes in this volume, we already “know whodunit.” States and corporations under public scrutiny frequently defer or delay accountability by promising to gather evidence and look into problems that are already well understood. Structural violences such as colonial occupation and environmental racism persist as open secrets, and you can’t expose what everyone already knows.{21} Moreover, exposing injustice with spectacular evidence of a single incident can end up concealing systemic patterns, making every acute revelation, simultaneously, a cover-up. Evidence can obfuscate as much as it illuminates. How do we get it to illuminate the right things?

The efficacy of evidence depends on forms of recognition that have never been evenly distributed. Throughout history and around the world, states orchestrate regimes of legal recognition that criminalize petty acts such as vandalism and drug use while denying legibility to deeper injustices, from predatory lending to medical apartheid. These regimes codify what LaCharles Ward terms “legal seeing”: the rules of admissibility that have historically excluded enslaved people, women, immigrants, and countless others from the possibility of having their evidence recognized at all.{22} In such contexts, the problem is not an absence of evidence but rather, as Rangan notes, “the absence of an institutional or social context”—a forum—in which that evidence “can be heard and validated.”{23} Making evidence work, as we elaborate below, is a matter not only of assembling proof, but also of assembling publics and building power.

Beyond the courts, too, believability is a resource allocated in accordance with power. Legal recognition dictates whose evidence counts, but so does cultural recognition. As Sarah Banet-Weiser and Kathryn Higgins have shown, the barrier faced by those whom society has constructed as being less credible is “not their lack of evidence but, rather, their lack of evidentiary authority.”{24} Media can insidiously undermine that authority even as they circulate documentary evidence. For example, when legacy news outlets brand video footage as “unverified/activist footage,” or when they qualify reports of massacres in Gaza by attributing them to “Hamas-run” institutions, they sow what Stefan Tarnowski identifies as an institutional form of plausible deniability that makes “denials stick and accusations slip.”{25} Cleaving knowledge from belief, such disclaimers don’t deny or repress evidence, but they prevaricate: “They preface or postface” it to maintain doubt “as to what might ‘actually’ have happened and who is ‘really’ responsible.”{26} While Israeli officials themselves treat the Gazan health ministry’s numbers as credible behind closed doors, the seeds of doubt take root across public cultures.{27}

One response is that practiced by counterforensic agencies and human rights organizations that leverage their evidentiary authority to verify “unverified” reports. The rise of generative AI has only intensified the drive toward authentication, turbocharging vicious cycles of validating and debunking that consume digital cultures of the post-truth era. Yet, in her analysis of pro- and anti-choice activism in this volume, Rose Rowson argues that rebuttal is a losing strategy because it allows one’s opponents to set the rhetorical ground. Opponents run around the master’s house in circles while the house itself remains intact. Another response, then, is waged at a longer-term scale by cultural workers and social movements that struggle to redistribute evidentiary authority altogether.

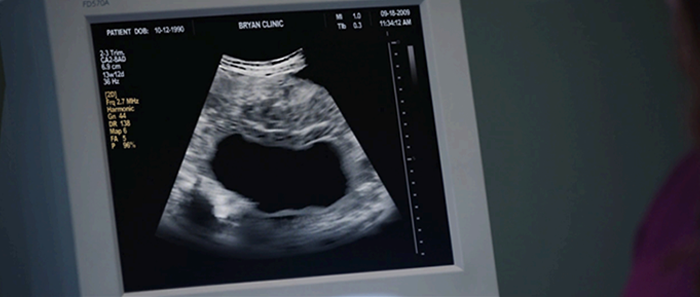

UNPLANNED (Cary Solomon and Chuck Konzelman, 2019).

UNPLANNED (Cary Solomon and Chuck Konzelman, 2019).

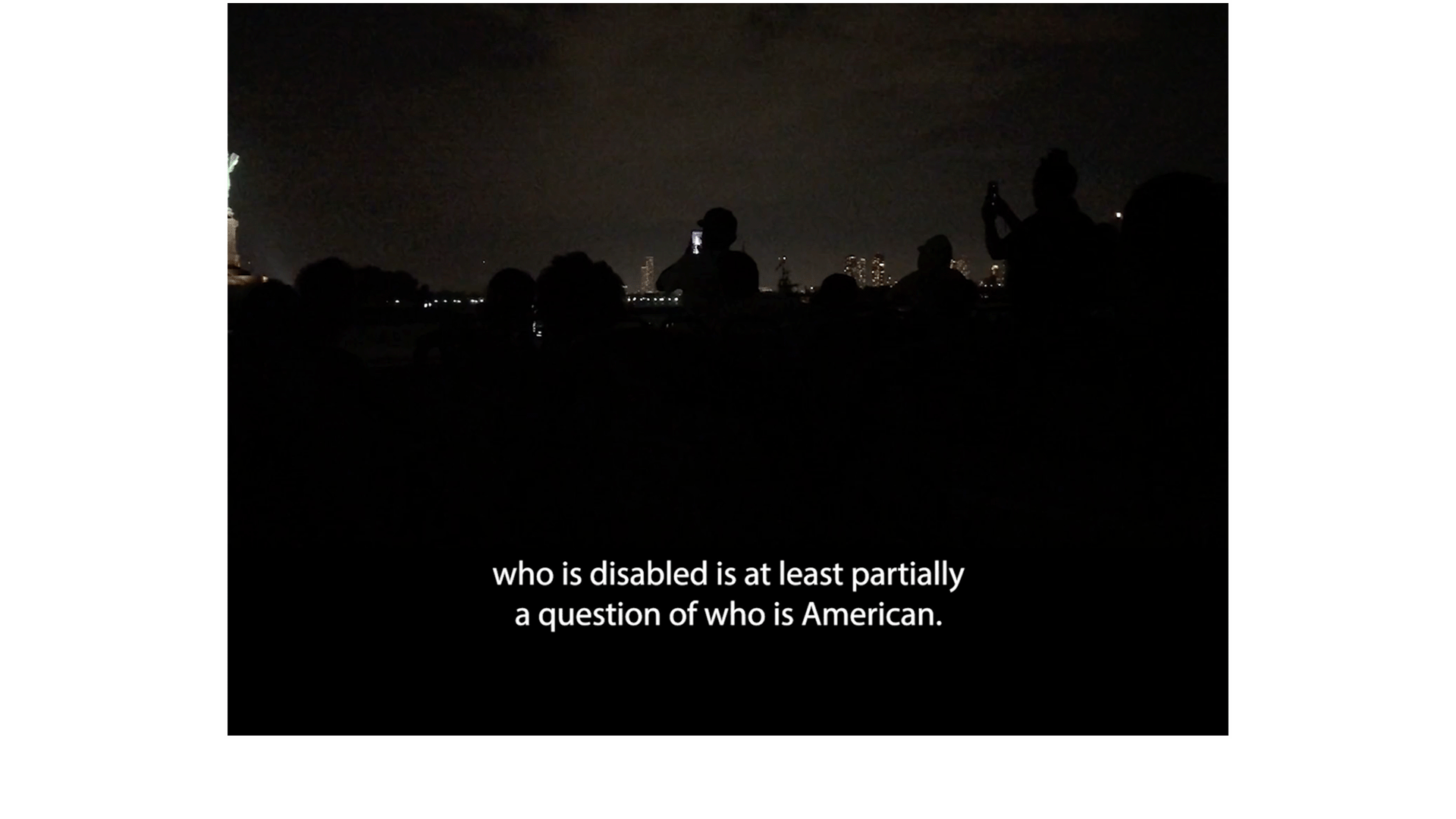

Recognizing that evidence never speaks for itself, documentaries have often sought to amplify silenced perspectives and histories, conferring legibility on those struggles. Similarly, forensic experts present themselves as the translators of the mute speech of bones, bullets, and other inanimate objects.{28} In both cases, mediation broadens the terrain of admissibility by allowing silenced witnesses to be heard, but the criteria for recognition are imposed from the outside. Critiques of humanitarian media have emphasized that speaking-for is an act of ventriloquism.{29} Turning people into evidence can be instrumentalizing and even violent because to humanize someone is to first accept the premise of their inhumanity, then fit their life into a normative mold. For example, Jordan Lord and Emma Ben Ayoun discuss in this volume how states and nonprofits exploit images of disabled workers as visual proof of institutional benevolence. In response, Lord develops aesthetic strategies aimed at abolishing cultural practices that conscript disabled bodies to serve as evidence of someone else’s charity.

Activists have found forensic methods to be strategically useful because they already command cultural and legal authority. Can it be subversive to appropriate that authority, or do we always end up reifying it? Or, does this very dichotomy obscure a more complex field of strategic compromises? When contemplating Lorde’s counsel that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” one can get lost in the technicalities of the tools and lose sight of the bigger picture. Gilmore’s response—that if the master loses control of the means of production, he is no longer the master—may appear to counter Lorde’s assertion. Similarly, this volume’s polysemic analysis of just evidence as both indispensable and insufficient may seem to reproduce a simple binary. But, crucially, Lorde and Gilmore agree on a more fundamental point. It’s not enough to defeat or detain the master; you need to dismantle his house. Though the struggle for evidentiary authority can backfire when it merely fortifies the house’s foundations, artists and activists continue to deploy just evidence to dismantle repressive forms of authority and establish new ones in their place.

****

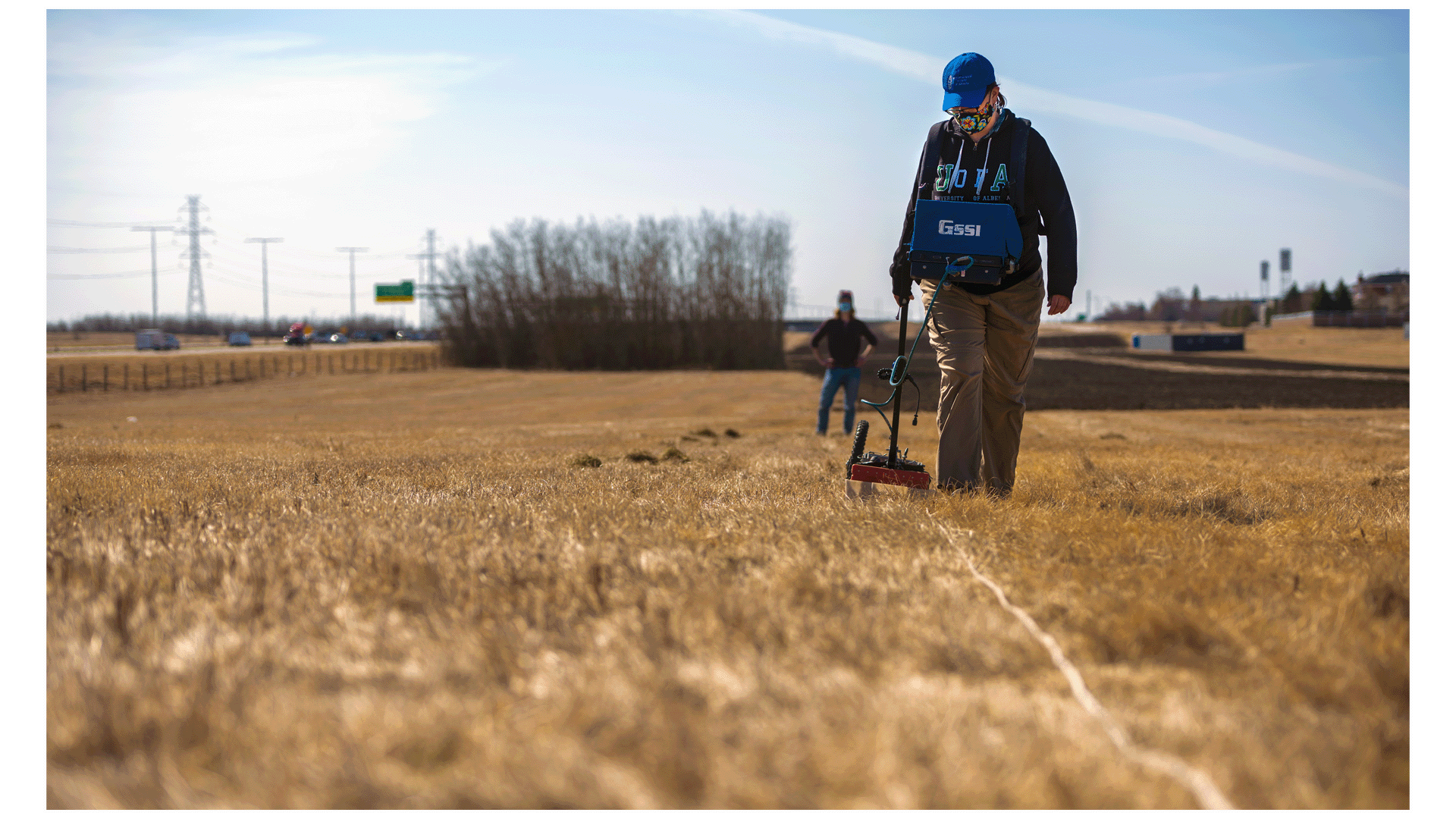

If evidence is both indispensable and insufficient, obfuscatory and illuminating, new methods of sensemaking are required. Whether working in commercial, artistic, activist, or professional contexts, documentary practices use media to make their visions of just evidence sensible. This volume assembles a diverse range of such practices, including documentary films, experimental video, courtroom drawings, medical visualizations, art cinema, public exhibitions, ground-penetrating radar displays, and protest images, among others. The contributors investigate what forms of justice these practices ratify, foreclose, and imagine. In each case, aesthetics mediate encounters with evidence and configure what kinds of worlds it can be recruited to build.

Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman distinguish between sensing and sensemaking in their book Investigative Aesthetics. For them, sensing is a passive registration of raw sensory evidence, whereas sensemaking denotes the active, situated process of turning sensations into knowledge. As an analytic, sensemaking draws attention to the contextual dimensions of interpretation and translation; it may attune us to the contingent conditions under which evidence is made, validated, and fought over. Hegemonic modes of sensemaking present themselves as merely sensing; they perpetuate the positivist fallacy that evidence exists objectively in the world, awaiting discovery, extraction of knowledge, and the subsequent imposition of judgment. Seemingly critical practices collude with repressive forms of evidentiary authority when they invest in positivist fantasies that obscure the active work of sensemaking.

Juridical forms of sensemaking continue to monopolize ways that popular media interpret issues of violence and accountability. Their prominence reflects a persistent desire to naturalize narrow, institutionally codified approaches to justice and accountability. In their article for this volume, Başak Ertür and Alisa Lebow term this “documentary legalism,” a form of sensemaking that risks turning documentary itself into an arm of the law. As they write, “Such uncritical investment in modern law’s capacity for achieving truth and justice risks partaking in . . . law’s ‘sclerosis of judgment,’ and thus jettisoning a more capacious set of aesthetic resources for judgment.” Documentary legalism leverages structural, stylistic, and narratological similarities between legal process and cinema, often subordinating the act of filmmaking to legal requirements. It extends legal seeing to the domain of documentary culture, training viewers to see and listen like a state.

Documentary legalism infects our ways of sensing, knowing, and even feeling. For instance, the overwhelming popularity of true crime indexes a troubling field of libidinal politics that continually reorchestrates desires for closure and catharsis. In Brett Story’s article, she examines how the relationship between catharsis and justice in Western culture operates as an “affective currency” upholding “carceral common sense.” For Story, popular media that conflate retributive emotional relief with justice end up instilling desires for easy carceral fixes that entrench the prison-industrial complex. Leaving the systemic origins of harm intact, catharsis becomes a palliative remedy and an insidious demand that channels legitimate desires into carceral outcomes. Cathartic emotions may seem to arise spontaneously as presocial expressions of an authentic selfhood, but they are in fact organized by institutions of sensemaking, from movies that feel like trials to trials that feel like movies.{30}

ABC NEWS, January 23, 2018.

ABC NEWS, January 23, 2018.

Looking, listening, and feeling beyond such strictures, this volume explores aesthetic practices that fracture legal sensemaking’s illusory coherence and unity. Contributors explore how these fractures open escape routes to alternative forms of redress. In contrast to the hegemonic forms of evidence discussed above, this volume positions irresolution and uncertainty as potential vehicles rather than obstacles to knowledge. Most explicitly, Price’s article identifies an “ethics of irresolution” as a common thread woven through a diverse range of contemporary Afro-diasporic video artworks. Similarly, in Laliv Melamed and Pooja Rangan’s discussion with the Al-Haq Forensic Architecture Investigation (FAI) Unit and Rachel Nelson (Visualizing Abolition), they describe a decolonial methodology that insists “on the political primacy of the fragmentary, the anecdotal, and the remembered over the accuracy and stability of legally admissible evidence,” precisely because they still work with institutions that have historically dispossessed or disenfranchised Palestinians. Along with these contributors, we reject the truth of true crime: its techno-solutionism, its hunt for conclusive answers, and its drive toward legal judgment as its teleological endpoint. We remain committed to truth, but as an open-ended process of material and social inquiry, not a juridical terminus.

Indeed, revising, reopening, and returning emerge as abiding themes across this volume’s experiments in sensemaking. Miranda Pennell’s photo-essay returns to her film Man number 4 (2024), a granular, fragmentary deconstruction of an image of Palestinians detained by the Israel Defense Forces in Beit Lahia, northern Gaza, in December 2023. Through annotation and critical reflection, Pennell revisits the process of the film’s creation and her own ethical positionality. Similarly, Ben Ayoun and Lord discuss Lord’s revision to their 2024 film An All-Around Feel Good, which demands that the institution exhibiting their film, the New York Film Festival, sever ties with funders of the genocide in Gaza and the ongoing settler-colonial oppression in the West Bank. Ertür and Lebow’s engagement with Philip Scheffner’s 2012 film Revision—which revisits the 1992 killing of undocumented Roma workers on the German-Polish border—is itself a revised and expanded version of an earlier essay.{31} Whereas traditional modes of sensemaking pursue fixity and closure, the practices we center approach the evidentiary as a terrain of interpretive dispute open to persistent contestation.

Alternative modes of evidentiary sensemaking may reject finality in favor of open propositions and transformations. They do not reject the value of evidence, but they embody different orientations toward verification. They recognize the social and historical contingencies shaping the contexts in which evidence becomes evidence of, and they locate, in that indeterminate status, the potential to open new horizons of possibility. Here, evidence functions as a fulcrum: a means through which emergent claims can be articulated and dominant narratives destabilized. In charting these directions of evidentiary practice, we draw inspiration from abolitionist and decolonial visions that offer both critical and creative perspectives on what might constitute justice. Though often mischaracterized as oppositional programs, abolition and decolonization are resolutely affirmative projects that set out to transform the world. They carve out space for alternative futures to be collectively imagined. The reason we dismantle the master’s house is, as Gilmore puts it, “so that we can recycle the materials to institutions of our own design.”{32} Because information only acquires significance when contextualized, evidence creates worlds. These worlds can be closed systems or open propositions.

Excerpt from REVISION (Philip Scheffner, 2012).

****

Media assemble spectators, choreograph forums, and create publics. They orchestrate social relations. Evidentiary tools may reinforce, renovate, or fundamentally reimagine the architecture of the master’s house. And architectures have rules. Whether explicitly or tacitly, every forum conditions what kinds of proof it can recognize, what testimonies it will hear, what stories can be told. Legal orders’ restrictive criteria delimiting what counts as evidence and harm have led many to pursue justice in alternative forums—from news media to people’s tribunals—where publics replace judges and juries in adjudicating the truth and its consequences. On one hand, this move from the juridical to the popular may augment capitalism’s erosion of public institutions. Kelli Moore’s contribution to the volume resists this tendency by returning to the courts—and to practices of courtwatching that reclaim legal spectatorship from the logics of entertainment. On the other hand, media may construct forums that present alternatives to both state- and corporate-led processes of investigation and accountability. As Ertür and Lebow demonstrate, cinema may itself construct “cine-tribunals” that contest the hermetic procedurality of legal trials by opening spaces of common sensing that direct reflexive attention to the rules that govern the forum. Lord’s film An All-Around Feel Good achieves something similar by drawing attention to the mercenaries funding the film’s very exhibition. Whether in mounting an incomplete exhibition (as Visualizing Abolition did) or teaching a contentious film (as Story discusses), the presentation of evidence functions as a generative act: It produces contexts in which collectives assemble, have difficult conversations, form coalitions, and build power. Evidence becomes more than just evidence by organizing publics.

Situating evidence within the social allows us to foreground its relationality: Evidence to whom? And for whom? When the collecting of documentary evidence prioritizes legal standards of admissibility, even activist investigations can end up subordinating their own interests to those of the state.{33} Alternatively, abolitionist and decolonial perspectives refuse to equate (settler) law with justice. For example, in movements for transformative justice, accountability is a process without an endpoint, one whose principles are context-dependent and collectively defined.{34} What counts as evidence depends on what we want to transform about the world. When Métis archaeologist Kisha Supernant (interviewed in this volume) employs remote-sensing technologies to search for burial sites on the grounds of former genocidal institutions, she is not driven by juridical imperatives to corroborate oral histories with material facts or to prove what Indigenous peoples already know about colonial violence. In fact, she rejects the logic of verification that prioritizes the epistemic requirements of settler institutions over knowledge held by impacted communities and, frequently, of documents over collective memories. Supernant gathers evidence to support healing and reparative justice, not to apply or solicit legal judgment. This orientation resonates with Al-Haq’s refusal to depose testimony to the bottom of an evidentiary hierarchy—their approach to verification is a community-based process, not a technological guarantee. While both Supernant and Al-Haq employ expert tools of remote sensing and digital analysis, they ground their methods in relations of reciprocity. They are thus less concerned with the aesthetic thrust of what accountability looks like—a question that may be settled on representational terrain—and instead emphasize how we “become answerable for what we learn how to see.”{35} Supernant’s and Al-Haq’s practices of gathering, analyzing, and sharing just evidence are driven by social (not legal) questions generated by those resisting genocide, not those adjudicating whether it is happening at all.

While true-crime narratives may begin, superficially, as mysteries, juridical sensemaking already knows where it’s going: It applies laws and standards, presupposing outcomes in advance. Instead, this volume privileges evidentiary practices that pose the status of justice as a question, not the answer. What constitutes justice? Who gets to decide? By widening the aperture beyond media texts to their contexts, we turn attention to the forums through which evidence is made meaningful and actionable—to the social forces informing what evidence is and what it could become.

****

Writing in the summer of 2025, we find ourselves at a conjuncture where evidence and the institutions tasked with its creation and care are under persistent attack. Around the world, authoritarian leaders criminalize medicine, censor researchers, destroy archives, defy legal judgments, and obstruct and murder journalists. Of course, these conditions aren’t new to everyone. While they may be increasingly visible to many in the Global North, assaults on the evidentiary have long been realities in diverse Global Majority contexts where regimes have persistently targeted the means of truth production, memory-making, redress, and repair. These global histories remind us that evidence’s institutions have never served everyone—that preservation and destruction, knowing and unknowing, remembering and dismembering are intricately entwined. Such conditions amplify the ambivalence of just evidence; they compel us to assert its value and to recognize that such assertions achieve nothing on their own. This moment has further accentuated at once the importance and the impotence of the evidentiary. Its futures will depend on the social forces that harness, champion, and make sense of it.

Background videos: The Extrajudicial Killing of Shireen Abu Akleh, 11 May 2022

(Al-Haq, 2022) \ Sous le ciel des fétiches (Under the Sky of Fetishes) (Caroline Déodat, 2023)

{1} See, for example, Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth (Verso, 2021); Erika Balsom, “The Reality-Based Community,” e-flux journal 83 (2017).

{2} See, for example, Galen Stocking et al., “A Profile of the Top-Ranked Podcasts in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, June 15, 2023; “True Crime,” YouGov, September 13, 2022.

{3} Karl Marx, “Theses on Feuerbach,” in Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy, ed. Frederick Engels (Foreign Languages Press, 1976), 65. Examples of this subgenre include Making a Murderer (Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos, 2015–18); The Staircase (Antonio Campos, 2022); and The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst (Andrew Jarecki, 2015–24).

{4} Pooja Rangan and Brett Story, “Four Propositions on True Crime and Abolition,” World Records Journal 5 (2021).

{5} Max Liboiron, Pollution Is Colonialism (Duke University Press, 2021), 134.

{6} Sasha Crawford-Holland and Patrick Brian Smith, “Forensics,” in The Lab Book: Situated Practices in Media Studies, ed. Darren Wershler et al. (University of Minnesota Press, 2022), accessed May 14, 2025.

{7} See, for example, Yuval Abraham, “‘Lavender’: The AI Machine Directing Israel’s Bombing Spree in Gaza,” +972 Magazine, April 3, 2024; Bethan McKernan and Harry Davies, “‘The Machine Did It Coldly’: Israel Used AI to Identify 37,000 Hamas Targets,” Guardian, April 3, 2024. As UN Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese writes, “Surveillance and incarceration technologies, ordinarily used to enforce segregation/apartheid, have evolved into tools for indiscriminate targeting of the Palestinian population.” See “From Economy of Occupation to Economy of Genocide,” Human Rights Council, United Nations, June 30, 2025.

{8} Bea Abbott and Nick Lally, “Counter-forensics and the Geographies of Images,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 43, no. 1 (February 2025): abstract.

{9} Patrick Brian Smith and Ryan Watson, “Mediated Forensics and Militant Evidence: Rethinking the Camera as Weapon,” Media, Culture & Society 45, no. 1 (2023): 54.

{10} Crawford-Holland and Smith, “Forensics.”

{11} Thomas Keenan, “Counter-forensics and Photography,” Grey Room, no. 55 (Spring 2014): 68.

{12} Thomas Keenan, “Getting the dead to tell me what happened: Justice, Prosopopoeia, and Forensic Afterlives,” Kronos 44 (November 2018): 120.

{13} Pooja Rangan, The Documentary Audit: Listening and the Limits of Accountability (Columbia University Press, 2025), 128.

{14} Alabama State Sovereignty Commission, “Propaganda Film about the Selma to Montgomery March,” Alabama Department of Archives & History, accessed July 25, 2025.

{15} Leigh Raiford, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle (University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 79.

{16} Nicole R. Fleetwood, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (Harvard University Press, 2020), 58–59.

{17} Quoted in Aniko Bodroghkozy, Equal Time: Television and the Civil Rights Movement (University of Illinois Press, 2012), 2.

{18} Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Duke University Press, 2015), 21–22.

{19} Armond R. Towns, On Black Media Philosophy (University of California Press, 2022), 112.

{20} Raiford, Luminous Glare, 144–45.

{21} See Laliv Melamed, “A NonReport: The Operative Image and the Politics of the Public Secret,” Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 62, no. 4 (Summer 2023): 33–56; Sarah Banet-Weiser and Kathryn Claire Higgins, Believability: Sexual Violence, Media, and the Politics of Doubt (Polity, 2023).

{22} LaCharles Ward, “Somebody’s—Or Nothing: Visual Evidence, Blackness, and the Limits of Legal Seeing,” History of Photography 45, no. 3 (2021): 363–75.

{23} Rangan, Documentary Audit, 142.

{24} Banet-Weiser and Higgins, Believability, 115.

{25} Stefan Tarnowski, “Plausible Deniability: On Media Siege, Media Activists, and Epistemic Murk,” in The Denial of Genocide in the Digital Age, ed. Bedross Der Matossian (University of Nebraska Press, forthcoming).

{26} Tarnowski, “Plausible Deniability.”

{27} Mitchell Prothero, “Israeli Intelligence Has Deemed Hamas-Run Health Ministry’s Death Toll Figures Generally Accurate,” Vice News, January 25, 2024.

{28} See Keenan, “Getting the dead”; Eyal Weizman, Forensic Architecture: Violence at the Threshold of Detectability (Zone Books, 2017).

{29} See Pooja Rangan, Immediations: The Humanitarian Impulse in Documentary (Duke University Press, 2017); Trinh T. Minh-ha, When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender and Cultural Politics (Routledge, 1991).

{30} On these mutual resonances, see Carol Clover, “Law and the Order of Popular Culture,” in Law in the Domains of Culture, ed. Austin Sarat and Thomas R. Kearns (University of Michigan Press, 1998), 97–120.

{31} For the previous version, see Alisa Lebow and Başak Ertür, ‘“Wo Beginnen’” [Where to begin? Revision as method], in Grenzfälle: Dokumentarische Praxis Zwischen Film Und Literatur Bei Merle Kröger Und Philip Scheffner [Borderline cases: Documentary practice between film and literature with Merle Kröger and Philip Scheffner], ed. Nicole Wolf (Vorwerk 8, 2021).

{32} Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Public Enemies and Private Intellectuals: Apartheid USA,” Race & Class 31, no.1 (1993): 70.

{33} Sasha Crawford-Holland, Patrick Brian Smith, and Andrew Williams, “Law’s Capture of Human Rights Focused Open-Source Investigation,” London Review of International Law 13, no. 1 (March 2025): 93–113.

{34} See Mariame Kaba, We Do This ’til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice, ed. Tamara Nopper (Haymarket Books, 2021); Pinko, After Accountability: A Critical Genealogy of a Concept (Haymarket Books, 2025).

{35} Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (Autumn 1988): 583.