Conditions: Warren Sack in conversation with Jenny Reardon and Bonnie Honig

Warren Sack, Jenny Reardon and Bonnie Honig

I first read Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition about twenty years ago, when social media was just taking off. I found in Arendt’s notions of the private, the public, and the social a way to understand the social in social media. Ever since then, I have continued to reread Arendt for insights into the newest trends in media technology. In my latest book, The Software Arts (MIT Press, 2019), I make use of Arendt’s distinction between work and labor to distinguish information from computation and narrate a new history of both. In general, I am wary of anachronistic applications of theories of the past to conditions of the present, but one should not apply Arendt. One must instead examine a question as Arendt might have done and try to reanimate Arendt to think through our present conditions. Arendt inspires this course of action in the prologue to The Human Condition:

The trouble concerns the fact that the “truths” of the modern scientific world view, though they can be demonstrated in mathematical formulas and proved technologically, will no longer lend themselves to normal expression in speech and thought. The moment these “truths” are spoken of conceptually and coherently, the resulting statements will be “not perhaps as meaningless as a ‘triangular circle’, but much more so than a ‘winged lion’” (Erwin Schrodinger). We do not yet know whether this situation is final. But it could be that we, who are earth-bound creatures and have begun to act as though we were dwellers of the universe, will forever be unable to understand, that is, to think and speak about the things which nevertheless we are able to do. In this case, it would be as though our brain, which constitutes the physical, material condition of our thoughts, were unable to follow what we do, so that from now on we would indeed need artificial machines to do our thinking and speaking.{1}

We now live with smartphones and machine learning and artificial intelligence. Have we yielded our thinking to machines, as Arendt feared? Can we only demonstrate what we know in mathematical formulas and new technologies? Or, can we take up the challenge she throws down: to render the truths of today’s world in normal expression of speech and thought? To take up this challenge is to engage in the struggle to see and to act within the politics of contemporary new media technologies.

The Human Condition was published in 1958. The prologue begins with a passage on the first artificial satellite, Sputnik I, launched on October 4, 1957 by the Soviet Union. This was the beginning of the so-called Space Age, a zeitgeist that I remember distinctly as a child of the 1960s and 1970s. Now, in the Information Age, our sights are fixed not on the stars, but our social media feeds. The difference for the technologists was wryly phrased by the billionaire Peter Thiel: “we wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” But, if the Information Age is a technological disappointment, it is also a political morass.

In the late fall of 2019, Jenny Reardon, Bonnie Honig, and I met twice for a trialogue to discuss questions like these: what are the prevailing trends in science, biotech, and software engineering? What kinds of trajectories are implied by computational theory and machine learning? What are the risks of these developing fields as they come into contact with modes of privatized, bureaucratic rationality, or with statism and surveillance? How does Arendt’s work help us think more deeply about these questions?

—Warren Sack

Jenny Reardon

How do collectivities form in this moment of widespread critique of dominant institutions: banks; the European Union; home ownership? The university too is under critique; post-WWII institutions are falling apart and you have new media moving into the governing space they formerly occupied. Earlier than that, the computer transformed from a threat of control into a promise of liberation, as Fred Turner’s work shows. A lot of people who work in genomics today were inspired by the vision that informatics was going to give people the power to recreate the world. In the case of genetics, the belief was that we can recreate life. But now we’re reaching the limits of that vision. Over the last few decades, folks moved out of computer science into the life sciences because they wanted to do good—to cure cancer rather than create another geolocation app. The genome became a gathering point partly because it offered up the possibility of doing good and fostering life. Now, though, biotech itself is coming under scrutiny for concentrating wealth and health into the bodies of the few.

Bonnie Honig

Some of the critique you develop in The Postgenomic Condition has to do with the way that the genome project interacted with capitalism and with other social and political forces. If we look at how capitalism is part of the picture, then we see some people are coming into the genome project, looking to do good, like you just said, but some are pulled in by more entrepreneurial aspirations, right?

JR

I think of Anne Wojcicki as an emblematic figure here. At the time she started 23andMe she was married to Sergey Brin, the cofounder of Google, and they have a son named Benji. When Benji is born, they make it known that Brin’s mother has Parkinson’s. One of the reasons for 23andMe is to find new treatments for Parkinson’s so if Benji has the genetic variant that predisposes him to disease, there might be new treatments, or even a cure. If you listen to folks in biotech, which I had a chance to do last week at a dinner conversation organized by the Atlantic, you will hear them foreground again and again this story about their commitment to curing disease and saving lives. When asked by the dinner conversation moderator if they had a responsibility for the SF housing crisis they responded: “No. IT, information technology, is responsible for all the Google buses, and the focus on making money. We are different. We are mission-oriented. We want to cure diseases.” They really see themselves as not about the money, even though money is there. We also spoke that evening about whether this narrative was reaching a tipping point. Could this narrative last? To ask this question is to be impolite in the Arendtian sense, in the sense of breaking the polity. The kind of writing and work that I do is Arendtian in that it attempts to narrate the genome as a site of agonism and politics. It interrupts the origin story of the Human Genome Project as a heroic public effort to improve human understanding and health. For some genome scientists, that feels rather impolite . . .

BH

The way you tell the story in The Postgenomic Condition is very complimentary to the aspirations that different people bring to the project. But, at the same time, your version of the story might not be their preferred version because, as you tell it, they are not the heroes of the story. In the second chapter, when you talk about the conventional founding narratives, you say these are the heroes of that conventional version of the story, but not your version. Page du Bois says of her work in classics that she wants to topple the hero. You do that too.

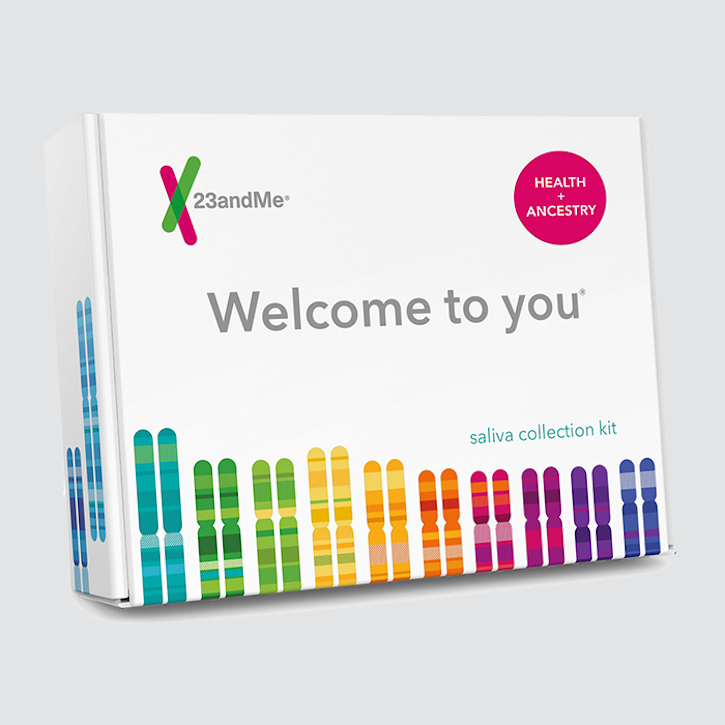

Figure 2. 23andMe genetic testing kit.

Figure 2. 23andMe genetic testing kit.

Warren Sack

Jenny, the biotechnologists are trying to position the human genome as a thing of the public if they’re saying things like we don’t care about the money, this is for the public good, this is going to help health everywhere. That’s what I understand from your book. But is the genome a thing of the public? A similar shift is happening in software. It can be periodized according to who was assumed to be the normative user of software. In the old days it was the military and insurance companies, and then it was big business. After that was the introduction of the personal computer and software intended for the individual consumer at home. Now social media is not just for the individual, but for friends, family, and colleagues. New innovations in software are made when designers create software for a new group of people. For example, when computer scientist Alan Kay focused on the child as the user, innovations like the laptop (Kay’s vision of the Dynabook) and object-oriented programming (Kay’s contributions to the programming language Smalltalk) became prominent. Innovations emerge when there is a shift in the vision of the normative user. In the rhetoric of the social media companies, like Facebook, there is a stated goal to shift to the citizen as the canonical user and, thereby, a shift to describe these platforms as things of the public. But they are falling short of this goal.

BH

Facebook is saying, more or less: This is what social media for citizenship looks like. We are not censoring—reading political speech for content—we’re just giving you access to everything (we’re not passing our own personal judgments too much, only around the edges for the extremes). They are practicing a kind of liberal neutrality over content. The claim then is: it is up to us. We choose. But that is not neutral. Leaving it up to us means leaving it up to them, since they are organized and we, scripted as individual choosers, are not (yet). Individual choosers are not the same thing as citizens. Moreover, Facebook does make non-neutral decisions about what to feature on the site and whom to support with donations (they co-hosted, with the conservative Federalist Society, a dinner for Brett Kavanaugh, for example).

JR

Arendt becomes useful here by her insistence on a distinction between the social and the political. What about a political media as opposed to a social media? There is a lot of concern about social media’s echo chamber, that we’ve created a social—in the Arendtian sense—media that makes us conform . . .

BH

That lacks plurality.

JR

Yeah, that’s right.

BH

That’s the key feature for Arendt. An Arendtian political media for citizenship would be fundamentally committed to plurality and even to what William Connolly calls pluralization (to protect against future homogenization).

JR

Right, and I think that’s a good way of diagnosing what a lot of people are struggling with right now with social media. How do you design that plurality? Warren, these are questions at the heart of your work. I think the other thing that unites all of us is a concern with the political. To what extent is the political a project of the democratic? To what extent do we hold onto democracy as the aspirational political form?

WS

The common complaint about contemporary social media—and genomic data as well—is that private data is being aggregated and sold for profit. This seems to me quite concordant with the distaste Arendt holds for the social, of appropriating the public for . . .

BH

Private gain?

WS

Yes! Bonnie points out that the social is a contested territory of politics exactly because it mixes these things together. But the recurrent diagnosis of what’s wrong with contemporary Silicon Valley business models is that it’s all based on an advertising model, aggregating everybody’s data and selling it off. Reading Jenny, I see a homology between that and what’s going on in biotech.

JR

There is a need for the issue of the public versus the private to be understood in this current moment in conversation with Arendt and some of the work Bonnie has done to reread Arendt’s insistence on the separation between the public and the private. The big story of the Human Genome Project was we’re saving the genome for the public. The story was the fight between the public and the private effort. It was very important that a distinction be maintained between the public and the private for the genome to become an object of collective concern. Because if it was just another site where someone was profiting, there is no way it would have become a site of collective action, a thing we should mobilize around and put our efforts into. This university, UC Santa Cruz, one of the main stories it tells about why it’s a great place is that . . .

WS

UC Santa Cruz saved the genome from private enclosure!

JR

Right! If the genome is the quote-unquote book of life, then we (UCSC) built the shelf that you could put it on to make sure there was public access. “We gave you the bookshelves.” And that’s in fact how folks talked about it. Now, let’s fast forward twenty years to today, and now you hear talk about how there’s no way you could study a genome without private investment. It’s just too expensive.

BH

What does that mean? Is it more expensive than the last 18 years in Afghanistan? Because we have some very expensive public projects. When we say something’s too expensive, I think, OK, how expensive is it?

WS

(jokingly) Trillions of dollars?

JR

OK, let’s think of NIH’s budget . . .

BH

The Washington Post just did a story today about how much we’ve spent on nation-building in Afghanistan since the US invaded. It’s an astronomical number. In the US, some things are just not thought of in terms of their affordability, no matter how much they cost; some kinds of investment are assumed to be simply indispensable. Why not this, then?

JR

I think it’s a both and situation. Genomics has brought the most expensive approach to biology we have ever seen. Now we could mobilize public funds to support it. And there might be something to the narrative that it exceeds the capacity of the public. The latter story justifies the entrance of massive new amounts of private funding into the life sciences.

BH

And the other thing that could be happening in the background is other considerations having an impact. Not just costs, but race. You write about this some in your book and I do too, in Public Things: historically, in the United States, things are public until they become racially mixed, and then they are made private. For example, researchers appropriated, in an extractivist way, cells from Henrietta Lacks and others; they experimented on people of color, and acquired scientific knowledge, and made profitable progress and products. Sometimes, if there was an objection, the heirs of those used for this purpose might get some compensation. But now, having derived an entire industry and mode of inquiry through the extraction of things of value from the bodies of people of color, suddenly the claim is oh, but the project is too big, it has to be done through private funding, it can’t be public anymore. Can’t it? I wonder. Look at what happens when the question becomes not whether the research should be public but rather who owns the cells. If the question is who owns the HeLa sequence? the solution comes to appear obvious: just pay the family some money and give them health benefits. But the real issue is: is this public? If it is, then everyone must benefit from it, in some true sense of public: all races, all classes, all genders. And that is when we hear: it’s too expensive, we need private industry. So the story here has to be part of a racial politics story too. I think it’s really important: In the US you can never separate marketization or privatization from racial division and white supremacy.

JR

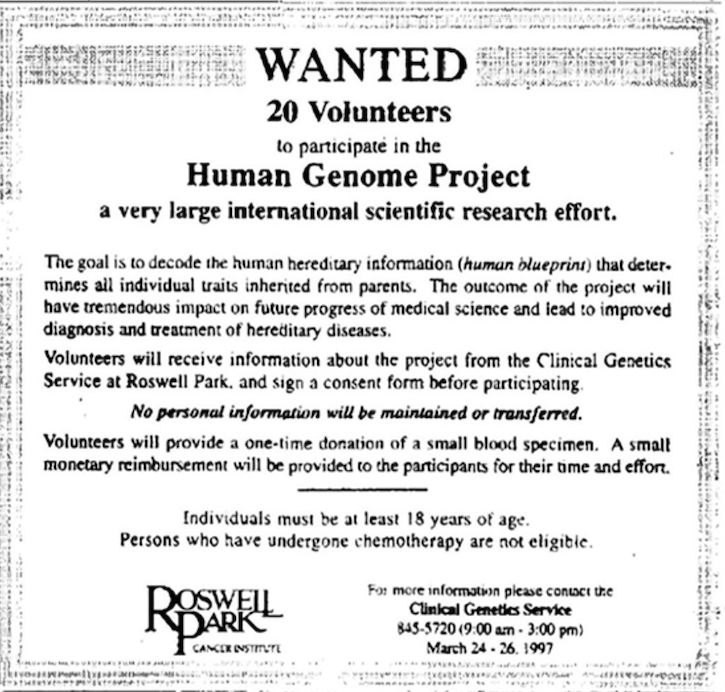

The genome is a great example of that. After the genome was sequenced there was a question about who was the human of the human genome. It was someone from Buffalo, NY who responded to a 1-800 number. Within an hour of placing that number in a local newspaper, a whole bunch of people called in, and of those people they selected 10, and randomly sequenced one. I’ve always wanted to write a little article exploring that story. That person, whoever they were, ended up having lots of rare variants. So now we are at our university going back and creating the standard diverse human. At every single point in the genome, the question is what is the most common variant, as opposed to the one that we randomly got from that person in Buffalo? My point is that no one could do anything with just this one random individual’s genome. Everybody knew that we were going to have to sequence all kinds of people in order to make sense of the human genome.

BH

That’s the big data part. (laughter)

JR

Yeah, that’s the big data part. And that big data project is rife with problems of how to deal with the question of race. There was a big push to get samples from people of African descent, because they were thought to be the most diverse. But the critique was that you’re just going to take those samples, get the variation, then you’re going to develop drugs for people who have the money to pay for them. The All of Us project, the US government’s effort to study human genetic variation, has attempted to address this, but there’s different problems with this. First, there’s distrust. Even if you do want to represent and serve folks who have not been represented, you have the problem of distrust in these communities. Second, the cost of the drugs coming out of genomics are some of the most expensive we have ever seen.

Figure 3. An ad that appeared on March 23, 1997, in the Buffalo News. Placed by Pieter J.

De Jong, PhD, the ad asked volunteers to provide blood samples from which DNA could be

extracted.

Figure 3. An ad that appeared on March 23, 1997, in the Buffalo News. Placed by Pieter J.

De Jong, PhD, the ad asked volunteers to provide blood samples from which DNA could be

extracted.

WS

You, Jenny, are asking: for whom do the deliverables of big data projects work? Let’s also pose another question about big data projects: do their productions actually work for anyone? There’s scant evidence that genomics has advanced medicine, but that’s hardly unique. One would be justified in skepticism about the productions of practically any big data project, not just genomics. I’ve been interested in a set of other claims that big data and machine learning have contributed to the solution of longstanding problems in computer science. For example, machine translation has been a benchmark ever since Warren Weaver wrote a memorandum in 1949 proposing that computers could be used to translate texts. Currently, Google’s Translation system is said to be the best and was, in 2016, completely redesigned using techniques of big data and machine learning. It is trumpeted as a success of big data. But if you are bilingual, you can very easily demonstrate that it doesn’t work at all as a translator. It can help you correct your spelling, it can help you conjugate verbs, but it does not translate: it does not perform the task it is advertised to perform. Douglas Hofstadter had a very nice little article in the Atlantic last year showing how poorly Google Translate performs in the several languages he speaks (including French and Chinese). In her book Artificial Unintelligence, Meredith Broussard says we’ve become so enamored with having things in the digital form that we no longer care whether they work. This, I fear, is a very accurate diagnosis: there is a popular concern with the uses of big data, but few worry whether the results do what they are advertised to do. In terms of public things, this could be a disaster. We will live just fine without machine translation, but what if the future generation of cars are self-driving but they don’t actually work? What if the future is in personalized medicine but it doesn’t work?

BH

Things get touted like that because that’s how they fundraise. But there is no guarantee that the things promised will ever be produced. Partly because it’s not public, so there is less oversight to see to that, and partly because they are over-promising. They are not going to produce miracle cures for diseases in the promised ways, since we’re also developing new diseases. We will never become un-diseased.

WS

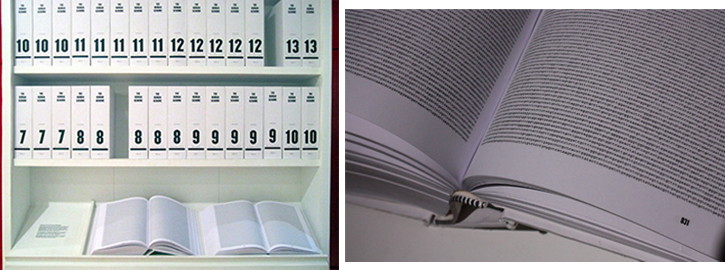

I worry the problem runs deeper than the bad rhetorics of fundraising and advertising. I worry that the productions of big data don’t work because at the core of the disciplines responsible for these productions the very idea of meaning was abandoned long ago. That their productions have no meaning should come as no surprise. In my book The Software Arts I characterize this as the computational condition. For me, the computational condition is when meaning has been put to the margins in a manner evident in logic, linguistics, and computing of the 20th century, when the grand theorists said meaning is of no interest. For example, David Hilbert, who set the agenda for formalist mathematics of the twentieth century—from Gödel to Turing and into the theory of computation—intended meaning to be omitted from mathematics. Noam Chomsky stated that meaning should not be a concern of linguistics. Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver, the founders of information and communication theory, argue that information has nothing to do with meaning. In her book, Jenny recounts seeing a printout of the whole human genome, volume after volume, thousands and thousands of pages. But no one knows how to interpret it, no one knows what it means. And yet, why should anyone know? Not just big data enthusiasts, but all of computing has picked a methodology that excludes meaning from its foundations. If one wants one’s work to mean something, one shouldn’t employ methods founded on the exclusion of meaning as a first principle.

BH

They didn’t want to do meaning, though. They wanted to formalize what they might have thought of as the raw material for understanding.

Figure 4. Printout of the human genome displayed in the Wellcome Collection, London, UK.

Figure 4. Printout of the human genome displayed in the Wellcome Collection, London, UK.

WS

That’s exactly what Hilbert is talking about.

BH

Could we say that they didn’t think about the possible effects of formalization, whether people might be changed, in turn, by formalization and how they might become less good at things we take for granted, like meaning-making? This is at least a possibility. It seems to me that when we assess certain things as public things, we are asking how they orient us to each other and in relationship to the world—and in plurality in Arendtian terms. The question is as apt for the seemingly less thing-y things like genomics and software, which also position us in relation to each other, as it is for more obviously thing-like things, like the table, right?

Look at how we seated ourselves, around this object, the table, in this room we are in now. There were other places to sit in this room but the table drew us to it, we set down our books, and positioned ourselves around it in relationship to each other. As Arendt says, the table is part of a material “in-between” (knocks on table) that allows us to congregate and talk to each other. In Public Things, I pay close attention to her section on Work in The Human Condition. The Work section describes where the world’s furniture comes from and why it is important to Action. The products of Work provide us with points of orientation in the world. Things position us in relationship to each other and provide us with insulations from others as well as with connections to them. Meaning is generated by our interactions across lines of difference and commonality, that is to say, in a world that resists formalization. So, if you just take meaning out of everything so as to have this formal language, something that doesn’t come from anything and is therefore pure, that kind of purity is like being in an unfurnished room: bare and disorienting.

WS

There are two practices of making meaning with big data. As I noted, making meaning is hard to do with the theories and methods of disciplines in which meaning has been pushed to the margins. Nevertheless, one approach to making meaning with big data is visualization. Visualizations are usually rendered as enormous diagrams with no obvious meaning. The other approach is the application of machine learning to discern repeated patterns or trends in the data. The newest forms of machine learning—like deep neural networks—are forms of data compression. Machine learning is, more or less, a process of analyzing the data to try to find the shortest computer program or mathematical formula that summarizes it. But current techniques are restricted to a search for formulas of a very limited kind. For example, deep neural network learning is essentially a technique to tune the parameters of large polynomials. How large? Well, a polynomial, for example, that runs as the engine behind Google Translate is over a billion terms long. Too big for any of us to read, much less understand. This puts us, epistemologically, in a really strange position. In 2008, Chris Anderson wrote an editorial for Wired, “The End of Theory: The Data Deluge Makes the Scientific Method Obsolete,” claiming that as long as we have lots of data we no longer need any theories. I think he didn’t really understand that theories have not been lost from the realm of big data, rather they just take another form, a bizarre form: billion term polynomials are now what are advanced as theories. Old science had short equations as theories, equations like Newton’s F = ma. Data science has billion term polynomials as theories.

BH

What’s really interesting is how those developments, which do seem to precipitate some kind of episteme, come along with the evacuation of other kinds of public things that may be more orientating for us, and which are linked to care and concern for others. Arendt notes something like what you’ve just described when she talks about Galileo’s telescope. Looking through it was a disorienting experience, phenomenologically: to look into space from earth and see the earth in the universe, as one planet among others.

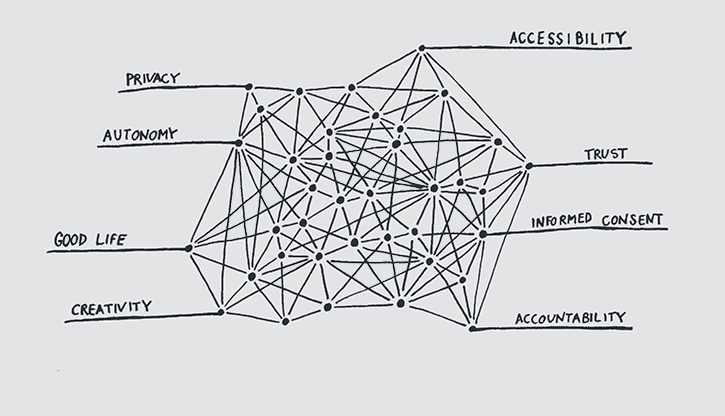

The example of Galileo is not that different from more recent examples of disorientation now. Indeed, in a recent Arendt-inspired report, called The Ethics of Coding: a Report on the Algorithmic Condition, the authors, who are code ethicists, make a similar point: they note that Arendt’s proposal for The Human Condition begins with the Sputnik 1 satellite, which repositioned us again in relation to outer space. They argue that the algorithmic condition repositions us in a similar way now. They even point out that The Human Condition was written at a moment of a “booming cybernetics society (amid) the development of information infrastructures.”

Now, what you describe, Warren, is very much like the experience these code ethicists are looking at; when we say a table orients us, it does that phenomenologically. If we thought of the table scientifically, as a bunch of molecules, it would not orient us. I think the problem of public things isn’t just about how, epistemologically we can now see things in such magnified forms that are beyond our comprehension; it is that those new experiences are not partnered with other kinds of public groundings that could perhaps anchor them, and us. Those code ethicists recommend community-based action in concert as a counter-weight. Is that enough? It has to be, in a way, but it isn’t.

Figure 5. Graphic included in the DATA ETHICS DECISION AID, a handbook for assessing ethical issues with regard

to data projects, developed by the Utrecht Data School in conjunction with The Ethics of Coding project.

Figure 5. Graphic included in the DATA ETHICS DECISION AID, a handbook for assessing ethical issues with regard

to data projects, developed by the Utrecht Data School in conjunction with The Ethics of Coding project.

WS

If we talk about public things, let’s also discuss what elsewhere in the social sciences would be called institutions. I speak Norwegian, so when I think of the English word thing I also think of the Norwegian translation, ting. The Norwegian parliament is called the Storting—literally the big thing, but what might be better translated into English as the great assembly. It’s an institution, not just an object; an institution that assembles people governed by a set of rules. So in Norwegian there is no clear distinction between a thing and an institution. How might we make the distinction between a thing and an institution?

BH

I’m not sure there is a difference. So, one of the things that’s quite interesting about the way that philosophers always go to the table as an example of something simple and obvious that you could then build your phenomenology around . . .

WS

A round table discussion has a round table in it!

BH

Right. Or it did once, and then the metaphor left the table behind. This suggests that, sometimes, once we’ve all become habituated to an object, the object becomes dispensable. Even if there is no table, people will often congregate in a circular form in order to have a discussion. But is that why tables were built in the round? Or do we gather that way because we once had round tables?

Even more interesting is that the table is not just a table at all. For example, kitchen table talk, in feminist circles, say, refers not to the power of the table per se, but to the condensation in the table of past experiences around it. That is why there is a feminist press called Kitchen Table Press. The name captures the feelings of power and enchantment that many feminists know from sitting at kitchen tables, planning, plotting, and talking. It condenses experiences of intimacy and sorority for feminists. Conversely, but relatedly, when Sara Ahmed talks about the role of the table in phenomenology, in Queer Phenomenology, she points out that the table functions as a fixed point for a thinker like Husserl, but that it does so because his wife has cleaned it, prepared it, quieted the environment for him to work. That’s the patriarchal table, the philosopher’s table, but there’s also, still, the kitchen table, where different kinds of ideas may gather. So things that seem to exist independently of us are soaked with meaning. Today, the dining room table is where kids do homework, guests are welcomed, a parent might write a book, and/or the Passover commemoration of release from slavery is observed. Which comes first? The object or the use? It is a chicken and egg problem.

JR

That chicken and egg problem is the right one to think about. When the genome was attempting to create its public, it faced the question of who was going to use this thing, the genome? And the Federal Drug Administration said, you can’t go out there and get people to use this because you don’t know what it is, and what could it do! And so in the beginning there was no advertising for 23andMe. You had to be in the know to be part of constituting the genome . . .

BH

Part of the bespoke-ness that’s in the DNA of the genome. (laughter) There is this quality in genome products like 23andMe that’s like, this is just uniquely for you.

JR

And it became the hip thing to do. It was in the Style section of the New York Times. They did spit parties during Fashion Week! Spitting in a tube to get your DNA sequenced was the new glamorous thing to do. Beyond the hip, the other group they recruited were skydivers. Those were the three constituencies they went for: the rich and famous; the in-the-know Silicon Valley hip people, and the skydivers. They were the genome’s publics.

Figure 6. An image accompanying the NEW YORK TIMES Style Section article, “When in Doubt, Spit It Out,” September 12th, 2008.

Figure 6. An image accompanying the NEW YORK TIMES Style Section article, “When in Doubt, Spit It Out,” September 12th, 2008.

BH

Well, if you’re willing to jump out of a plane, why wouldn’t you spit into a tube?

(Laughter)

JR

Here you are trying to constitute a new enchanted thing that will create a collectivity—the genome—but we have very little idea what it means or could be used for. Warren, what crosses over quite clearly between your work on the computational condition and my work on the postgenomic condition is that we’re looking at things—the information, the genome—that sideline meaning. During the Human Genome Project, Craig Venter, the scientist who led the private effort to sequence the human genome— the purportedly evil Craig Venter—at one point said, “I think we shouldn’t sequence the whole thing all at once. We need to stop and figure out what some of it means.” And there was a decision, an actual decision, made to not do this. I love Arendt’s demarking of the cis in decision to call our attention to the fact that de-cis-ions are about cutting.

Leaders of the HGP made a cut, and they said, no! We are going to sequence the whole thing, and then future generations can figure out what it means. But the problem with that is that they didn’t build into the institutional infrastructure of genomics any process for addressing the question of meaning. They said, we’ll do that later. And so now we’ve got a world where we’ve created this genome that is not meaningless, because there is meaning, but it’s not meaning in the . . .

BH

I think that what you’re describing is, in a way, captured by something that you quote in your book, which is Arendt’s injunction that we should think what we’re doing. And they decided not to stop and think what they were doing.

WS

Which had, as you narrate, big business implications, right? Because, then, building the sequencing machines becomes the thing.

JR

That was the thing! That’s right. That’s what they were doing.

WS

And that just blew up as a business.

JR

Yeah, and that’s what they’re still doing! They’re still building better sequencing machines.

BH

In The Human Condition, Arendt talks about how the French used to have an empire and when they lost their empire, suddenly they became very much in love with their bric-a-brac. (laughter) She suggests, in a way, that it is an overcompensation: deprived of the glory of empire, they invested themselves in miniatures in their private homes. The reason I mention this now is that Arendt is here inviting a critical interrogation of what we’re enamored with, and why. This goes back to what you said earlier, Warren, about how we’re too enamored with the form of the digital. And now you, Jenny, are describing how people are caught up by the progress that they’re making and they just don’t want to stop and think. They’re enamored also! And I’m thinking how important it is now to think not only about re-establishing the possibility of publicness and citizenship, but also about re-cultivating in people the capacity for refusal and practicing a sort of non-inevitabilization of progress. Ariella Azoulay talks about that in her new book, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism.

Jenny has described various moments in the genome project’s development when there were invitations or opportunities to refuse, to interrupt, to stop the temporality of inevitability and then we see: No, we’re not stopping. We’re just going to keep going. Sometimes going with the flow is a lot easier. And it’s the same with the form of the digital; it has a flow to it, as Warren has written. It’s very hard to stop the flow, but it isn’t impossible. We know how to do it! You need join up with others, congregate around a shared effort to open up what Arendt would have called a different time, a new line of time. That, it seems to me, is what the three of us share in our writing and thinking. As I was reading your work in preparation for this conversation, I was thinking, Wow! You know, we’re all humanists (laughter). The human, for Arendt, is the capacity to not just be swept up with the flow but to carve out our own time. This does not mean being a Bartleby, who just says no or prefers not to. It is more like the example of Muhammad Ali who refuses (I am thinking of his draft refusal) on behalf of a world he would like to belong to but doesn’t fully exist yet. He wants to open up a different line of time.

We can talk about it in terms of media. We are in a moment that can seem disempowering. It’s one of the challenges of our moment, but we’ve been there before. With the development of print media, for example, the medium seemed to invite the collapse of high and low culture. People worried that literacy might degrade rather than elevate people’s tastes and sensibilities. Once people could read, there was no telling or controlling what they might read! Romance novels were not what the enlightened philosophers had in mind. There have been many moments, historically, where there’ve been invitations to refuse and say, no, we want a different time. The Judaic Sabbath is an example of that: a no to 24/7 temporality even before we had a name for it.

JR

I think the topic of temporality is something to dwell on. In the genome world speed is, as the historian of genomics Mike Fortun has pointed out, constitutive of the genome. It is about speeding things up. You want faster and faster sequencing machines, you want the data . . .

BH

What’s the acceleration driven by?

JR

Multiple things. The argument is that we need a lot of data to make any meaning. And, in order for us to get there in any kind of time scale that we can imagine as being meaningful we need it to happen much faster. So, if we sequence DNA at the rate that I was doing it when I sequenced DNA back in 1994 it would be two centuries before we had the human genome. This is not in a timescale that anyone’s going to get behind. At the end of the day we were able to sequence one human genome in fifteen years. Now if we want to sequence a million people, we do not have 15 million years. The process had to speed up in order for it to be meaningful. And it has. Genomics has sped up technically and culturally. I was once talking to someone who works in genomics, and she said to me, “I don’t get up in the morning and plug myself in. I’m not a robot.” Finally, there is the argument that if we don’t speed up, people die.

BH

Really though they worry if they slow down, somebody else will beat them, though, don’t you think?

JR

Well, yeah, right!

WS

Bonnie, doesn’t this connect to some of what you were saying about Wendy Brown’s book, Undoing the Demos; how efficiency becomes like the master good, in some sense. And what you’re narrating now is the micropolitics and the rhetorical strategies that position efficiency or speed as the ultimate good, right?

JR

As life! And this is interesting because Arendt refuses life as a ground for politics.

BH

Exactly. She’s the earlier critic of biopolitics.

JR

I think that’s important, and as I read Arendt and reread Arendt, I always wonder what she would think today as life becomes completely reworked. It is no longer the unchangeable, but rather the site of change. It still has the kind of power over us that Arendt saw as the antithesis of politics because if I’m sick with sickle cell disease and you tell me you can use CRISPR to cut DNA and cure my sickle cell, you have power over me. It becomes very hard to refuse. So, I think there’s something about temporality, refusal, and life—their interplay— that denies the possibility of the political in an Arendtian sense.

BH

I think that’s right, but it is important that, for Arendt, contingency, which includes the condition of illness or accident that befalls us, is part and parcel of the human condition, and, so, efforts to change this might fundamentally alter the condition of being human, and this requires thinking, and maybe refusing! So often in science fiction novels, there are marginal communities or rogue families that have removed themselves from the new techno-world that others greet with welcome or resignation. We have that choice too. And we have to ask, as Arendt would: what would the human condition look like if, in utero, everybody was genetically cured of whatever diseases they were carrying before they were born (which is one possible direction we could end up going in)?

JR

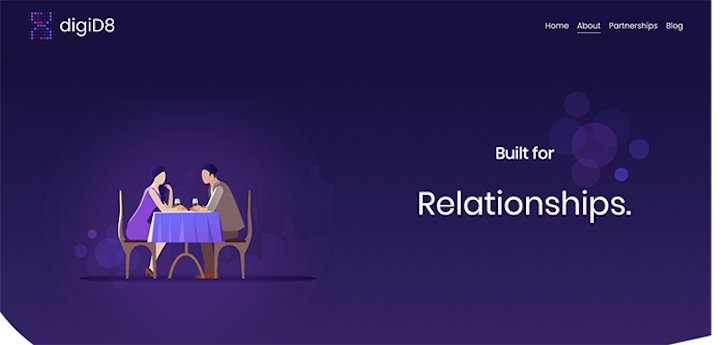

This is what the Harvard geneticist George Church just announced yesterday: a dating app that uses genomic data and algorithms to ensure you don’t fall in love with someone who has the same genetic variant for a disease as you. The idea is to avoid perpetuating seven thousand different diseases—to bring disease to an end through assortative mating guided by algorithms and genomic data.

BH

Yeah, and the casualties of that are things Arendt asks us to value: plurality, contingency, and not knowing. Not knowing is an important part of the capacity to have understanding. We are thinking in terms of problem-solving, efficiency, curing, but not in terms of the kinds of relationships that we need to have to survive the failures that await us too.

WS

Filmmakers and novelists have frequently speculated about how new technologies could change what it means to be human and transform our everyday world. This techno-imaginary does not just appear in science fiction but is also part and parcel of scientific discussion. For example, there are a lot of writers of non-fiction who claim we’re on the verge of developing a super-intelligence, a machine more intelligent than any of us. George Church’s discourse about genomics seems to inhabit an analogous techno-imaginary. These imaginaries are rhetorical strategies for gathering more and more resources to the technical work by driving public reception. For example, journalism’s expression of the techno-imaginary of AI would lead the public to believe that self-driving cars are just around the corner. Unfortunately, technically, we are not anywhere near a self-driving car practical for the everyday world!

Figure 7. from the website for Digid8, a dating app developed by Geneticist George Church.

Figure 7. from the website for Digid8, a dating app developed by Geneticist George Church.

BH

But you can see them on YouTube. (laughter) We’re nowhere near them, but you can see them.

JR

Or they might almost run you over in San Francisco where you see these self-driving cars with people in them training them.

WS

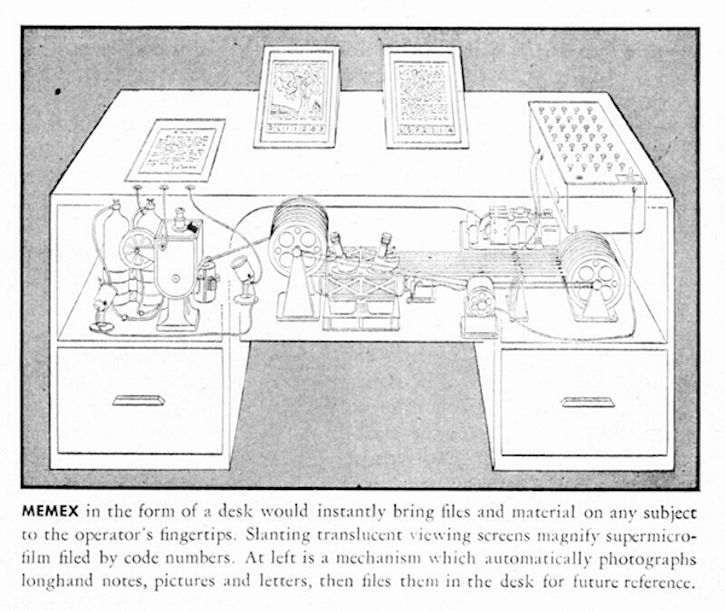

Right, but the fantasy is far from fact. And in some cases, when car owners have accepted fantasy as fact, disaster has struck. There are already examples of deaths caused by Tesla drivers who assumed the car could drive itself. There’s been a whole spate of videos on YouTube of people falling asleep at the wheel with the car in self-driving mode. On the one hand, we have real change driven by technology, like frantic news feeds of social media that interrupt everyday life 24/7. Some of these changes are of the magnitude of a change in the human condition but they are not the ones advertised. We are promised self-driving cars but receive, instead, 24/7 harassment. The promises and fantasies about technology are frequently diversionary tactics or advertising techniques that appear as early as Vannevar Bush’s 1945 Atlantic Monthly article, “As We May Think,” on the topic of hypertext. Bush’s rhetoric is repeated with variations today. In the article he cycles between tales of fantasy and what he knows as a maker of scientific instruments, the latter employed to convince us that the former — the fantasy — is credible or workable.

JR

I think it’s important to say both things. They don’t work and they do work. The question is what are they working to do?

WS

Well, that’s what I keep coming back to in my book: what does it mean to work?

JR

Yes, I think that the importance of the public is that it is a space where we get to ask who we are and what we ought to gather around and work towards. We are losing that space. We are transforming the public into an instrument of privatization. That is very clear in the case of the human genome. The genome is working to do certain things that were built into it to do. For example, it works to identify. This has been in the news a lot recently. The New York Times keeps covering these new surveillance powers of genomics—most recently genome scientists’ work with Chinese forensics authorities to develop techniques that have been used to surveil ethnic minorities in China. Media have focused on this issue because it is an area where genomics is working. Genomics has increased exponentially our ability to order people, to distinguish between this person and that person. So some things genomics does exceedingly well. They just are not the things we hoped for: the cure to cancer, the transcending of race. Genomics was supposed to prove we were all just human. It was supposed to preserve and augment the human.

BH

There has never been anything done in the name of augmenting the human that didn’t turn into a device of partitioning and surveillance! I’m just thinking with Foucault, you know: a technology that begins as a health technology ends up as a policing technology. The technology doesn’t carry its own guardrails within itself.

Figure 8. Drawing of Bush’s theoretical Memex machine. THE ATLANTIC MONTHLY, July, 1945.

Figure 8. Drawing of Bush’s theoretical Memex machine. THE ATLANTIC MONTHLY, July, 1945.

WS

I worry whether there is an intrinsic tendency for technology to always be authoritarian or warlike, or whether technological developments are mostly dependent upon funding. One can narrate, as Manuel DeLanda did in War in the Age of Intelligent Machines, the development of technology as a war effort. Analogously, one might see technology development as an outgrowth of surveillance. It might be traced back to Francis Galton and Alphonse Bertillon and those who invented statistics and so show computing to be just the newest apparatus for furthering fingerprinting and forensics. But have alternative technologies not been explored because, comparatively speaking, there has been no budget for such explorations? What’s happening in Silicon Valley today is a sad example of this. All of the social media companies are essentially advertising firms. One could do something else with social media except, relatively speaking, there is no budget to do so. If one wants a billion dollar company one has to capitulate to the advertising model and collect private data and sell it.

JR

Within the bio-world, you are also starting to see alternatives responding to all this precarity. My PhD student is working on open insulin, a project to create insulin in a manner that places it in an open space, not in a privatized space, so it is available to all. Alternatives like these are emerging. We just don’t know if they are going to be flashes in the pan.

WS

It could be that this kind of thinking is intrinsic to the medium itself—a sort of technological determinism. It could be simply that a finite number of business models work best, so that’s what everybody does: build guns, build snooping devices, and so forth. But I also think (and this is where a lot of my work goes to) that the fantasies that technologists have today are very old. They precede the business models. They precede even the antecedent media of what we call new media. And so, the histories of these fantasies …

JR

Old imaginaries for new technologies.

WS

The imaginaries are frequently fleshed out in books and films before they are made into working technologies. And, if you can articulate an alternative vision, that’s really powerful. And that’s where it does make a difference to write a book. There’s a lot of discounting of people who write books or make films, especially if you go to a code-oriented place like Silicon Valley, where they want to know, well, did you write the code? But, that’s just one mode of articulating these imaginaries. We must examine the history of these imaginaries taken by technologists to be goals. Such an examination is one way to rethink the current landscape of technology.

JR

Yes, we must think and imagine new possibilities. The biggest ethical problem that we face in genomics is the problem of thought. We must think, and part of that is developing our collective capacity to refuse. We’re not just all going to get on this train and ride it to dystopia. The thing that has always fascinated me about the genome is how it’s always both everything and nothing. But this is not livable! We do not live in everything and nothing. We live in particular places with particular relations. We have to revalue the public spaces where we can think across our differences and create these relations.

BH

Yes. But the way that you just said what you said makes me think that we’ve written the story in a kind of tragic form. In this narration, there’s this ambition to dominate, it accelerates, it knows no bounds, and then like in any Greek tragedy, at some point the hero falls. And when the hero falls, the Chorus always says: this is how man learns, by being subjected to the blows of fate. The idea is that you have to be beaten in order to learn not to be so ambitious, not to seek to dominate nature, women, kinship, or the gods. If we plot our challenges in tragic form, that has consequences for our thinking. It suggests that the only way that we may see some of the changes that we’re talking about is if someone is brought down and made to experience the blows of fate. It suggests that nothing else is going to stop the genome project other than some kind of blow of fate. A lot of the things that we’ve been talking about—accelerationism, extractivism—may fit that model, in which people come up against finitude. But tragedy counts on fate putting us back in our place. There’s no reason to think that that won’t happen (unfortunately, it could happen through climate catastrophe all too soon) but the risk of tragic plot is that we wait for fate.

Background Video: Visualization of human h9 embryonic stem cell line, mapped by UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute / A murmuration of Starlings / “Eugenic and Health Exhibit, Kansas State Free Fair,” 1929. Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society / Think (Charles and Ray Eames, 1964) / Animation by the Illumina corporation, demonstrating their “patterned flow cell technology.”

{1} Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (University of Chicago Press, 1958), 3.