Maia and the Boundaries of the Frame

Ra'anan Alexandrowicz

From the Flatbed Viewer to the Viewing Booth

A decade ago I was engaged in archival research for my documentary The Law in These Parts (2011). I was searching for images that would visualize the history of the post-1967 Israeli military occupation in Palestine, which entailed viewing hundreds of hours of footage from Israeli and foreign archives in a variety of film and video formats. It was a jarring experience. I was suddenly compelled to gaze at the evolution of this painful and frustrating piece of history—one that I was not merely observing, but which I have lived through and for which I bear some responsibility. But it was not only that, I realized. The overall mental picture created by the accumulation of hundreds of hours of documentation was disturbing on a professional level. It made me doubt something that as a documentary filmmaker I had taken for granted. It made me question the uses of documentary in advocating for human rights and social justice.

The Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip—The Occupation, as it is referred to by both Palestinians and Israelis—has been heavily documented and widely reported in Israeli visual media since its very inception. If we were to take stock of the critical nonfiction media works about the occupation created during the last half-century, we would easily find thousands of such pieces. I had always accepted the paradigm that the more that people were made aware of injustice and oppression, the less that oppression and injustice can endure. But now, thinking back to these media objects—thousands of news stories, documentary films, witness videos, and even fact-based comedies—prompts a question: how can we reconcile this extensive critical documentation of an ongoing human rights travesty with the apparent failure to end it? This question leads to another one, wider, but no less disturbing: how is it that a period in which the pain of others, in a variety of contexts across the globe, is seemingly more easily exposed and its tactics of enforcement are made knowable to publics more easily than ever before, such exposure does not necessarily lead to increased global solidarity? The intended audience of such media objects are the would-be link between the representation of reality and the change of reality. What did viewers see in the documentation of the occupation? What did they understand from it? I felt compelled to turn my gaze away from all those nonfiction films, reports, and videos, to the viewers who saw them. What if I could better understand how the viewers see images of the occupation, how viewers develop knowledge through their engagements with them, and how their sense of attachment to ethical and political commitments is strengthened or challenged in conjunction with them?

THE LAW IN THESE PARTS (Alexandrowicz, Israel, 2011).

I am not the first to ask this question. A long tradition of thought and practice seeking to transfer the authority of explaining images from the experts, the makers and critics of images, to the non-professional realm of ordinary people precedes my own. One well-known work in this tradition, for instance, is John Berger and Jean Mohr’s Another Way of Telling. In a chapter titled “What Did I See?,” Mohr presents his photographs to random spectators and asks them to describe the images in front of them. With this gesture, he surrenders the position of authority with regard to his own images and transfers it to the beholder. In most cases, what they articulated about the photos was not what Mohr expected them to focus on. Ariella Azoulay, whose reflections on photographic spectatorship are central to this essay, critiques the lineage of work that begins with Berger and Mohr’s book. Ever since their book was written in 1982, she writes:

the same feeling of “discovery” has been expressed in other writings on photography, and in different contexts. Often, these “discoveries” have been linked in one way or another with the way “ordinary” people (i.e. people who are not considered experts in photography) have been using photography. These people supposedly possess a certain kind of knowledge regarding the photographed image which helps us to understand that “photographs do not work as we had been taught.”{1}

It’s not only photography, but also cinema and television that have cultivated a small but stubborn lineage of work that turns the camera towards the viewer. Some examples are Chronicle of a Summer (1961, Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin) in which the participants of the film view it critically in the end; 10 Minutes Older (1978, Hertz Frank), which depicts a child’s affect as he watches an engaging theatre play; Reverse Television (1983, Bill Viola); Shirin (2008, Abbas Kiorostami); Visitors (2011, Godfrey Reggio); and even Channel 4’s reality show Gogglebox (2013-present). While not necessarily addressing social change or social justice, each of these works look back at their viewers, exploring the mystery of the human gaze at the moving image.

In the opening of Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag recounts a correspondence between Virginia Woolf and a prominent London lawyer that occurred during the Spanish Civil War. The lawyer wrote to ask Woolf, perhaps provocatively, “how in your opinion can we prevent war?”{2} Woolf questioned the validity of the lawyer’s question, and in lieu of an answer, she suggested they consider a hypothetical experiment: what would happen, she asked him, if they both looked at images of the atrocities of the war, images which were published weekly in those times. “Let us see,” she writes, “if when we look at the same photographs, we will feel the same things.” Inspired by Woolf’s thought experiment, I wondered if there was a way for me to contribute to the tradition of cinema that looks back at the spectator. I decided to try to use the tools of documentary to explore and depict the way meanings are created in the consciousness of viewers.

In late 2017, I invited several people at Temple University in Philadelphia, PA, to participate in a filmed viewing of some of the same recordings that had spurred these reflections: documentary footage of the Israeli Occupation. The idea of the project was to try to capture peoples’ experiences while they were immersed in the viewing of nonfiction images. For this purpose, I had set up a viewing booth of sorts in a lab-like basement space in the Film and Media Arts department at Temple. The small booth was equipped with a would-be interrotron that displayed video on a screen and at the same time, recorded the face of the viewer; as if from the point of view of the screen they were looking at.{3} When participants entered the room in which the booth was situated, they could see multiple screens, as well as a small crew which they had already been informed would be recording them. Once a participant entered the viewing booth, they were alone with the images, but remained in dialogue with me through an audio system. I then asked them to familiarize themselves with a rudimentary interface allowing them to choose videos and control their playback. I encouraged them to verbalize the thoughts and emotions that surfaced as they were viewing, as unstructured, raw, and associative as those thoughts may be. These thought-fragments, I hoped, could capture something of the internal dialogue that accompanies the experience of viewing. Listening in to a dialogue between a specific viewer and a specific image quickly demonstrates Woolf’s response to that lawyer: that people see images in highly idiosyncratic, if still socially constructed, ways. Thus, following a specific viewer’s internal dialogue allows us to reflect on the messy and contradictory processes by which we try to find our own position in the world through critical engagements with the images and sound that portray that world.

THE VIEWING BOOTH (Alexandrowicz, 2020).

****

Shooting Back

In an earlier issue of this publication, Jeffrey Skoller investigates videos recorded by amateurs in the context of confrontations with US law enforcement, highlighting some of the cinematic and social characteristics that link them as well as the political potentials that might be found through them.{4} Skoller takes such videos, captured by happenstance filmmakers, as a new and valid documentary form. For Skoller:

These happenstance filmmakers create a new cinema of present-time, often by turning on the camera and placing it between themselves and figures of state power and authority—sometimes destabilizing the power dynamic in situations they are witnessing or engaged in and other times highlighting the asymmetrical relations of state power and the citizens they are meant to serve . . . . these recordings often create new forms of attention through performance, drama, and character identification, as well as new forms of witnessing and documentation that might be capable of transforming public discourse and the political landscape.{5}

The nonfiction images that I decided to explore through the eyes of the participants of The Viewing Booth were recorded in a different geopolitical context than the ones that Skoller considers, but they nevertheless take part in the kind of work he names documentation of the contingencies of present-time.{6}

The emergence of personal cameras and the increasing ease of online video sharing in the past decade and a half has marked a transition for Palestinians living under Israeli occupation from more often being the subjects of documentation to themselves documenting their own conditions.{7} To briefly recount this transition, we need to flash back to the early 2000s, when mobile phone cameras were still novel, particularly in the West Bank and Gaza. Those that existed produced low- quality images and could not record large quantities of footage. Handycams, on the other hand, were becoming more and more affordable and grassroots activists as well as media organizations were bringing them into the occupied territories. Suddenly, the ubiquity of small cameras allowed for the capturing of numerous incidents that were previously much harder to depict. News organizations (and film productions) would publish such videos, exposing the harassment and assault of residents, illegal use of force and weapons against demonstrators, and other human rights violations. This new kind of image seemed to be getting unprecedented traction, popularizing the notion, at least among Israeli activist organizations, that additional documentation would be a useful mechanism for changing the situation because it would prompt more public debate within Israel and it would increase international attention and pressure from the outside.

The Israeli non-governmental organization (NGO) B’tselem, which has been operating under this media activist paradigm since 1989, long before digital video and photography was available in Israel/Palestine, demonstrates this investment in the transformative potentials of video. The organization’s mission is to document and expose human rights violations under the occupation. In 2005, the organization initiated a project called Shooting Back (which still operates today).{8} B’tselem distributed dozens of handycams to Palestinian residents of the West Bank and encouraged them to capture human rights abuses in their environment. The organization periodically collects these recordings and tries to leverage them in the political, judicial, and public arenas in which the Israeli occupation is being challenged. Following their lead, other human rights groups and local Palestinians started filming and disseminating similar materials online. Filming became, for many of us, an important aspect of the struggle against the occupation.{9} It shouldn’t have come as a surprise that in response, Israeli settlers and the Israeli army also began to record and distribute videos which sought to justify their own actions. Over the last decade and a half, thousands of videos of the occupation have been posted online. These videos constitute some of the most raw and immediate representations of the occupation. And they are there, online, for anyone who wants to see them.

Happenstance videos continue to transform modes of viewing nonfiction when they resist claims of objective narration, instead evoking a heightened reflexivity of the images, provoking a response not only towards the image itself, but also towards the disposition of the person filming it. When such documentary fragments go viral, they are viewed by much larger audiences than the documentaries that I make can ever hope to attract, and they make up an increasing share of many people’s news consumption.{10} The duration of the videos and the platforms on which they are viewed create a different kind of viewing culture. The captioning of such videos has a significant influence on their reception; they are often viewed multiple times, and they are responded to, verbally, on social networks, sometimes in real-time. Moreover, these documentary fragments are then often approached by spectators in ways that are more similar to photographs than documentary cinema. In films, moving images are typically situated within a structure that contextualizes them and controls their meaning. Thus, the serial quality of film images provides for a continuous and adjustable process of meaning making, writes Ariella Azoulay. In a photograph, however, “one cannot exceed the bordered frame and that which is not contained in it, unless one can then refer to another photograph (preferably one that either preceded or succeeded it).”{11}

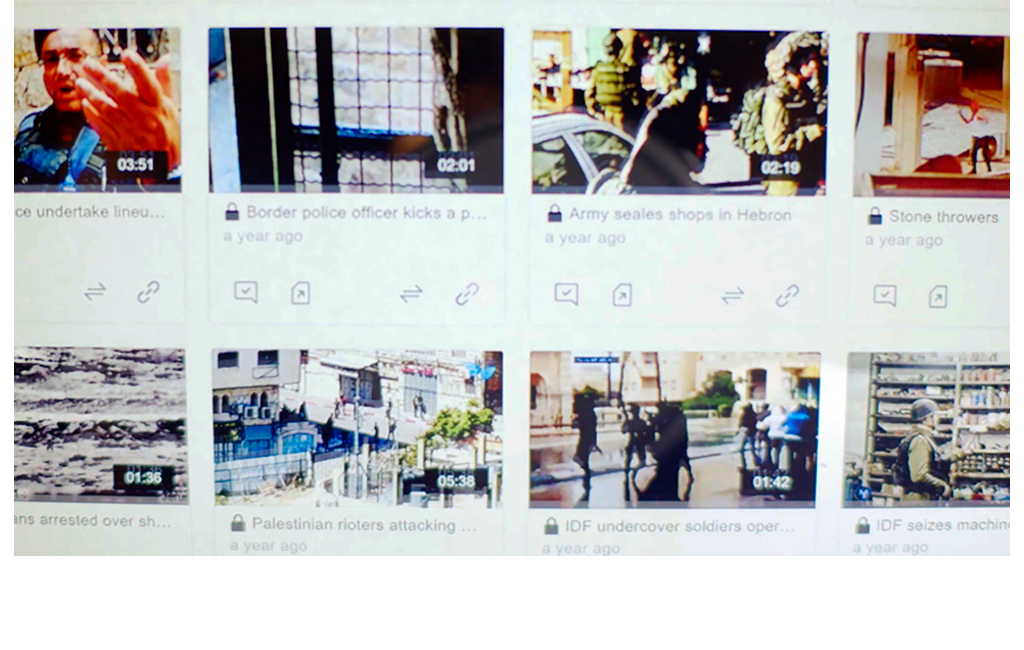

For participants in the viewing booth, I organized an archive of forty videos from the occupation. In an effort to neutralize some of my own biases, I decided that half of the videos would be ones that were shared by B’tselem, and the other half by conservative organizations that explicitly claim pro-occupation views.{12} Then, in December 2017, I issued an open call on the Temple University campus, soliciting people who are interested in Israel (but are not Israeli) to be filmed and recorded in the act of viewing. Seven students agreed to participate.

****

The Preferred Viewer

The Viewing Booth takes a case study approach, ultimately focusing on the experience of Maia Levy, one of the seven participating viewers. I had never met Maia before filming, but it was apparent to me from the start that the videos were engaging for her. She disclosed that her parents were actually from Israel, but I couldn’t discern her immediate disposition towards the images she chose to view. The first video Maia watched, Settler Violence Continues (B’tselem 2008), is a chaotic portrayal of an incident in the West Bank city of Hebron. A Palestinian man who cannot be seen is holding the camera and being assaulted, repeatedly, by a group of Israeli settlers who tell him to stop filming. As the man asserts his right to film, he is pushed around by military personnel who are present. They demand that he stop filming. Taking in the violent scene, Maia is speechless at first, but then, after I encourage her to watch the video again and verbalize her thoughts, she says:

the Arab . . . civilian wants to film . . . I guess . . . freedom of speech in some sense . . . but the soldiers and the religious settlers are really negating that. Like they don’t want anyone else to see what is going on there.

SETTLER VIOLENCE CONTINUES (B’tselem 2008).

Maia’s first responses give me the impression that she holds relatively liberal views regarding Israel/Palestine. After a while, though, moving through a few more videos, her responses began to clarify that her political inclination was different than I had thought. In the midst of watching the fourth video, one that portrays Israeli soldiers preforming an unwarranted and seemingly arbitrary search in a Palestinian shop, Maia stops the video, and then starts playing it again from the beginning. She explains that she is confused and that she can’t concentrate on the video because she finds B’tselem’s logo in the corner of the frame distracting. Before she starts the video again, I ask her what this logo makes her think. She responds:

That it’s going to be one of those propaganda, fake- not-real- skewed videos that just don’t even show the entire story. Or something really sad . . . . That’s why I think twice before I watch these things . . . . You know . . . Having Israeli parents, these videos kind of confuse me . . . yes . . . those videos they can really play with your head.

The way Maia describes the B’tselem human rights videos gives me a better sense of where she stands in political debate about the occupation. For Maia, videos portraying Palestinian suffering under Israeli occupation seem to be hostile images, because they threaten some of her fundamental beliefs by portraying asymmetrical Israeli aggression. She is, if to slightly distort Stuart Hall’s original term, an oppositional viewer of the B’tselem videos.{13} Arguably, for B’tselem, as well as for myself, oppositional viewers like Maia are actually preferred viewers.{14} Maia’s engagement with videos about the occupation is often referred to as moving “beyond the choir,” because it suggests an attempt to change rather than reaffirm “people’s perceptions and behaviours.”{15} Some of the other students who participated in The Viewing Booth also had doubts about the B’tselem footage, but Maia’s open hostility towards the organization, combined with her willingness to openly engage with the troubling images makes her the most dynamic of the seven participants. Empathy, anger, embarrassment, innate bias, healthy curiosity, and complex defense mechanisms—all played out before my eyes as I watched Maia watching the images of the occupation. This is why I decided to focus my film, The Viewing Booth, as well as this writing, on my experience with her.

****

An Oppositional Viewing

Over the course of the hour and fifty minutes that Maia Levy spends in the viewing booth, she watches eleven out of the forty videos that were available to her on the interface. This essay focuses on Maia’s responses to 2 out of the 11 videos she views. The first, published by B’tselem, is titled Soldiers Enter Hebron Home at Night (Da’ana, 2016). I will call it, for the purpose of this writing, Night Search. The second video is titled Israeli soldiers feeding Hungry Palestinian Children (maker and date unknown), and it was published by a right-wing online news outlet named 0404 News.

Night Search was filmed by Nayef Da’ana, a Palestinian resident of the city of Hebron in the Occupied Palestinian Territories and distributed by B’tselem. Da’ana documents, in a single 8-minute shot, Israeli soldiers raiding his home at 3 a.m. He records as soldiers wake his family, search their home, and snap pictures of the adults, children, and the premises. They do not provide the family members with a warrant, nor a reason for their actions, yet they do permit family members to record.{16} Though we see no physical violence, the video understandably shocks many viewers. Images of sleeping children being woken up to a house full of armed, masked military men who then interrogate them, rifle through their belongings, and photograph them without explanation demonstrates the acute vulnerability and precarious living situations that shape everyday life for many Palestinians under occupation. The invaded Da’ana family does not physically resist (apart from filming) and at the same time, it seems evident that the soldiers are taking no pleasure in the task they are performing. In a way, the video is most shocking for how mundane and routine the event appears to be.

from The THE VIEWING BOOTH (Alexandrowicz, 2020).

Maia is taken aback when she sees the soldiers aggressively enter the family home, put on masks, and shout demands at the Palestinian family. As the soldiers adamantly demand that the parents wake up all their kids and bring them out to the hallway, Maia responds:

Immediately when I see these things it makes me feel sad . . . . They’re kids . . . I mean, I imagine someone coming into my house and doing that . . . . It’s a little bit . . . difficult . . . . It’s not difficult to see, I can watch it but it makes me sympathize.

Nayef and Dalal Da’ana (the parents) argue with the soldiers, attempting to prevent their children from being inspected. Dalal says that the children are young, begging them to just look at them to confirm their age without further disrupting them. The officer does not agree and Dalal insists that it is too cold to take the children out of bed. Suddenly Maia’s attitude changes. She pauses the video in the middle of their argument and says:

But I also feel she’s lying . . . . I don’t know, I don’t trust her, they lie a lot too . . . it’s like she’s overdramatic . . . yeah it sucks but maybe you should just bring them out and it will be over.

Nevertheless, as Maia continues to watch, she seems to return to feeling empathy for the Palestinian children being woken up.

That’s sad . . . . They’re sleeping, and they are cute kids . . . it’s sad . . . . That’s definitely sad.

Again, this emotion does not last long. Maia suddenly complains that the video does not provide any context as to why this raid is happening.

The problem is that they don’t give any context. They don’t give you any context as to why they are doing this and that just makes them look bad. I mean . . . what if there is a complaint about a bomb in this house?

This swinging back and forth between empathy and suspicion continues throughout the first half of the video. Maia undergoes eight such shifts of attitude, moving between empathy and doubt. Finally, in the last few minutes, she settles into a fixed attitude of disbelief and distrust of the image in front of her. In the sixth minute of Night Search, the soldiers seem to conclude that they have accomplished what they came for. Without a word of explanation, they return the family’s IDs, and with a politeness that feels wholly ironic to the situation, they say goodbye to the dazed family members and leave. The door of the home, which was barged through minutes earlier, is closed gently by the last soldier to leave. Silence ensues. Then a surprising thing happens. The camera does not stop filming. It remains trained on the door for a few seconds and then pans 180 degrees, moving us back through the home, passing Da’ana’s confused 8-year-old daughter who stands frozen outside of her room. Da’ana continues recording as he tries to calm his kids, telling them not to be afraid and to go back to bed. Here, Maia does not empathize. She says:

And they make sure to film this part too, the aftermath . . . (she mocks the image) the “don’t be scared” . . . . It’s to show, to draw out . . . it’s like a movie. It’s an acted film. What would be the fun in cutting it right after they leave? What happens in the family after? People want to see that, and it makes you feel bad.

A child’s crying is heard, and the camera enters the bedroom where the kids were sleeping before the raid. Now we see that the child who is crying is one who was questioned briefly by the soldiers. As he notices his father approach with the camera he hides under a blanket. Not wanting to be seen or filmed. Maia continues to doubt the authenticity of the situation.

Of course . . . they are going to film a little breakdown of the kid after . . . . Added drama, very well played.

****

Expanding the Boundaries of the Frame

Maia’s viewing of the Night Search is dynamic. She moves back and forth between two dispositions, experiencing the video as it was ostensibly intended by its distributors while also critically deconstructing in real time the elements that produce empathic affect. When I viewed this video for the first time I found it to be a heart-wrenching piece of documentation. Maia’s equivocal responses surprised me. She was not totally dismissive of the Da’ana family’s suffering. It was as if she was negotiating it, to use Hall’s terms again. It was striking to see that whenever Maia moves away from feeling empathy for the family whose home was invaded, it was not because she transferred her sympathy to the invading soldiers. It was as if Maia distrusted her own feelings of empathy, moving her to then deconstruct the video’s message. She reminds herself that she is missing context. She imagines possible contexts in which she could accept the event as justified (“What if there was a complaint about a bomb?”); she problematizes the way the video was produced, spotting missing subtitles and speculating upon manipulated audio. Finally, she resorts to the assumption that the video was actually directed and that some of the moments of greatest pathos were, in her perception, acted. For me, what unites her varied responses is that they become based increasingly on unseen somethings that lie outside of the visible content of the frame (directing, subtitling, the mixing of audio). By imagining the circumstances of their production, Maia is able to reframe the images. A confrontational image such as a child being woken up in the middle of the night might be reframed as a man filming his child being woken up. The image a child crying after being questioned by soldiers might be reframed as a man filming his son crying. The reframed images locate agency more in the position of the father as film director, and less with the armed soldiers raiding a family’s home in the dead of night. In this way, Maia seems to be articulating her political affiliations through an aesthetic language that alternately describes and challenges the visible content within the video frame.

Maia’s interrogation of what rests outside the frame resonates with the writing of Ariella Azoulay, whose work also frequently engages the Israeli occupation of Palestine. For Azoulay:

That which has been framed in the photograph stands for a certain type of event, some generic matter such as “torture,” “expulsion,” or “refugees.” The borders of the frame are the bounds of the discussion. One cannot exceed the bordered frame and discuss that which is not contained in it, unless one can then refer to another photograph (preferably one that either preceded or succeeded it). In the absence of such a supplementary frame, one can only problematize the frame and question it.”{17}

While Azoulay refers to the viewing of still photographs, her observation is nevertheless applicable here. Maia criticizes Night Search again and again for its lack of context. As Maia repeats that response, I am tempted to suggest that the occupation itself provides plenty enough context to frame these images. And I am tempted to say that that in my view, the context of the invasion of a Palestinian home at 3 a.m. is clearly the total exercise of control by the Israeli military of Palestinian society in the occupied territories. I don’t say any of this, of course, as my role in the setup of The Viewing Booth is to listen to rather than contest the participants’ observations of the video footage. My hope is that Maia will zoom out to a wider image that includes the occupation—namely, that Israel is holding the West Bank under military occupation; that it is denying basic human rights to the indigenous inhabitants of these areas, and that it is transferring Jewish Israelis with full citizenship rights into the same areas to live in guarded enclaves. I want Maia to place the encounters portrayed in Night Search within this zoomed out frame in order to conclude that the political reality which has been in place (with certain alterations) for over five decades is what makes this violation of the occupied people’s space at 3 a.m. legally uncontestable. In my view, this tangible, longstanding context seems much more politically relevant to the video than the speculative context about an imagined bomb threat that Maia provides.

One of the ironies of this moment is that while I wish for Maia to step outside the boundaries of the frame in order to see a wider picture, she is in fact doing exactly that. Maia is stepping outside of the boundaries of the frame, but in a different way than I hope for. It is as if instead of stepping back and seeing a wider image that includes the occupation, Maia is stepping back to discover the person shooting, the camera, the memory card, which was transferred to the human rights organization, the computers that were used to post the video online, etc. I am wishing that Maia would zoom out to expand the boundaries of the frame on the X and Y axis—the political and historical context—while what she is doing is rather moving her vantage point back on the Z axis—revealing only the production context.

****

The Image is Stronger than the Image Makers

What I learn from Maia’s viewing thus far might be simplified into the following: Maia identifies images that threaten her world views, responding by reframing them in a way that allows her to read the images against the grain of their makers’ ostensible intentions. Alas, things are not quite that simple. Viewing, we should know by now, is a contradictory experience which is seldom reducible to binary models. The more I try to understand Maia, the more I find it difficult to clearly define the lines across which she and I differed in the way we view videos of the occupation.

Maia watches Israeli Soldiers Feeding Hungry Palestinian Children towards the end of her viewing session. The video, filmed by an anonymous Israeli videographer, runs for forty seconds. It is a vertically oriented video of low resolution, suggesting it was likely recorded on a cellphone. It was posted online by the right-wing Israeli media organization 0404 News.{18}

THE VIEWING BOOTH (Alexandrowicz, 2020).

Recorded one evening in the West Bank city of Hebron, the video shows two Palestinian children approach the camera from a distance. One of the children looks 3-4 years old, and the second, perhaps the brother of the young child, looks to be 6 or 7. The children are called from offscreen by a young male voice who seems to know one of the kids’ names—Ibrahim. As Ibrahim and his brother come closer, the camera pans to keep them in the frame. Now, we see it is an Israeli soldier (who had called out to the kids). He is holding what seems to be some bread and sliced cheese, which he is taking out of a bag while saying “Come over here, Ibrahim . . . we’ll divide it like brothers.” Ibrahim, waiting for the food, suddenly hugs the soldier’s leg lovingly. A second soldier steps into the frame and pats Ibrahim on the head fondly. The soldier with the food now gives both Ibrahim and the other child a sandwich each. The older boy starts devouring his piece of bread hungrily and they both turn to leave. The person holding the camera (most likely a third soldier himself) says: “Ibrahim! Say thank you!” Ibrahim stops, looks back at the camera and responds in his young, earnest voice: “Thank you!” The video then ends abruptly.

Maia does not respond as she watches the video. As it ends, though, she now appears somewhat confused. By this point I have come to understand that Maia is, in her words, “very pro-Israel,” and I expect that she will highlight the soldiers’ benevolent humanism, as other Viewing Booth participants did, and she will find nothing to criticize. Maia, however, says that she wants to watch the video again. She replays it, and to my surprise she starts criticizing it.

He’s running to him. Obviously, he trusts him, and it looks very staged . . . . I mean, when does this ever happen? Patting his head? . . . Holding his hand?

She finishes her second viewing and says nothing. I break the silence by reminding her that it was posted by an explicitly pro-Israel source. Maia responds:

Ok . . . so it’s probably a pro . . . pro-Israeli . . . make the IDF look good. But the truth is that when I see these things it looks very fake . . . I don’t know . . . not fake, it looks like . . . We get it, you’re promoting yourselves . . . . Also . . . they’re feeding them cheese like they’re dogs . . . like they are not really, like . . . people . . . . B’tselem videos show a lot of distress. This doesn’t show a lot of happiness. Feeding cheese to a couple of kids . . . A little silly even! “Say thank you!” she imitates the soldier. “Like they could have given them a couple of shekels beforehand to do this . . . These are two little kids.

It is striking to see Maia apply the same kind of doubt and criticism that she brought to Night Search. She was again stepping out of the border of the frame, and she was again doing it on what I called, earlier, the Z axis. Maia saw the event as possibly fake (I actually do not think that it is). She doesn’t believe situations like this exist (I actually do). As with Night Search, she considers the motivation of the people who shot, posted, and disseminated the video, and even assumes that the subjects of the video might have been paid for participating in it (while the children’s hunger is, to me, rather apparent). All of these aspects fall, again, outside the boundaries of the frame. But if I concluded earlier that Maia is going beyond the boundaries of the frame in order to reframe images which threaten her, why would she then turn her gaze outside of the frame in a pro-Israel video posted by a conservative outlet that promotes views that Maia shares?

Trying to make sense of this moment, I turn to another concept proposed by Ariella Azoulay: the idea of the civil gaze. In The Civil Contract of Photography, Azoulay introduces the concept of “the citizenry of photography.”{19} Photography, she claims, when it represents people or human conditions, transcends the technical, aesthetic, and political circumstances which are embedded into the image making. Photography cannot be reduced to the intentions of the photographer, nor a single distributor, viewer, or pictured subject, nor can it be reduced to being merely artistic or merely political. Rather, photography brackets a set of concrete conditions, and extends them across time and space. A photographed subject exists in relationship to a network of real and imagined viewers, whose joint participation in constructing the meaning of photographs also constructs a citizenry through photographs. This is why photography, as a public meeting space for viewers’ gazes, contains the potential for the equality of humans. This equality, Azoulay explains, which is often not granted to the subject of photography through the political systems governing them, can nevertheless be seen and imagined through their photographic depiction.

The photograph is never a sealed product that expresses the intention of a single player . . . the photograph does not make a truth claim nor does it refute other truth claims. Truth is not to be found in the photograph. The photograph merely divulges the traces of truth or its refutation. Their respective reconstruction depends on the practical gaze of citizens who do not assume that truth is sedimented in the photograph, ready to be revealed, but rather that truth is what is at stake between those who share the space of the photographed image and the world in which such an image has been made possible.{20}

While considering Maia’s response to Night Search, I assumed that she attempted to change its boundaries as a response to images that might otherwise challenge her world view. Conversely, her move outside the boundaries of the frame in Israeli Soldiers Feeding Hungry Palestinian Kids should be regarded similarly. It thus attests to Maia’s negotiation with the image, despite the fact that the video was meant to represent her side, so to speak, of the political argument. What I mean by that is that I assume that the soldiers who filmed Israeli Soldiers Feeding Hungry Palestinian Kids and posted it, did that because in their mind it showed first that they are loved by Palestinian children in the occupied city of Hebron and second that they are benevolent as they share their snack with the hungry Palestinian kids. Maia obviously sees something else in the image—she saw soldiers feeding kids as if they are not really people. She also assumes that they are trying, unsuccessfully in her eyes, to demonstrate something positive through it. “Truth,” to go back one last time to Azoulay’s words, “is what is at stake between those who share the space of the photographed image and the world in which such an image has been made possible.”{21} Despite the familiar logo that was superimposed over the video and the title Soldiers Feeding Hungry Palestinian Kids, Maia saw a disturbing image that once again challenged her world views, and which she needed to negotiate by reframing. The relationship between Maia and the hungry children in the photo is a demonstration, or so I see it, of Azoulay’s idea of the citizenry of photography. The humanity (or inhumanity) of the situation transcends the political aim of the makers of the video.

****

Looking Into a Cinematic Mirror

This essay offers no generalizable understanding about oppositional viewings of human rights videos. It does, however, intend to offer a reminder that it is not just videos, but also viewers themselves that perform the critical work of mediating our political realities. By turning our gaze to viewers’ negotiations with nonfiction images, we can better see how those images offer a starting point to work towards a world held equally in common. When I set off to film the seven Temple students who volunteered to watch videos from Israel, I had no idea that by seeing these videos through their eyes I would be inspired to explore the boundaries of the frame and to think in more expansive ways about the principles of a citizenry of photography at play. I would like to see The Viewing Booth as a model for a space that allows the spectators of images and the producers of images to explore how images are viewed and perceived in the present conjuncture, even if it points to other difficult questions. After all, doing the political work of developing contexts in which images can help us work toward, instead of distracting us from, social justice requires an effort that can’t be done by video alone. Still, perhaps through such cinematic introspection we can discover, in the spirit of Azoulay’s work, ways in which images might function for humanity; ways that we might not be using to their full potential whenever we remove actual viewers from the process of assigning meanings to images themselves. Perhaps through the employment of patient techniques such as the one I tried, we might create mirrors to our work; mirrors that reflect back upon us different ways forward in this age of hypermediation.

****

Acknowledgements

I thank Maia Levy, whose candid thoughts are the foundation of this essay, and to Nayef Da’ana whose courageous self-taught filming ability created an unforgettable, important image that this essay focuses on. My thanks go to Jeff Rush, Nora Alter, Chris Cagle, Liat Hasenfratz, and Chisu-Teresa Ko for their generous and insightful suggestions, to the Center for Curiosity in New York, the Temple University Film and Media Arts department, and the Sundance Documentary Film Program for their support of this project. I am grateful to Liran Atzmor for his partnership and continuous support of my work and thank you to the editors at World Records who led me through the enlightening process of writing this essay.

Title Video: The Viewing Booth (Alexandrowicz, 2020)

{1} Ariella Azoulay, “Getting Rid of the Distinction between the Aesthetic and the Political,” Theory, Culture & Society 27, no. 7-8 (2010): 241.

{2} Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (London: Penguin Books, 2019), 3.

{3} The Interrotron is the name director Errol Morris gave his technique of filming interviews through a teleprompter. The prompter reflected Morris’ image to the interviewee, so that when the interviewee was looking at Morris, they were looking dead into the lens. My adaptation of this technique created a situation in which the viewer was viewing video screened over the lens of the camera.

{4} Jeffrey Skoller, “iDocument Police: Contingency, Resistance, and the Precarious Present,” World Records Journal 1 (2018): (link).

{5} Ibid.

{6} Ibid.

{7} See more in Sandra Ristovska and Monroe Price, Visual Imagery and Human Rights Practice (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

{8} Shooting Back was modeled on the practices of the U.S. based human rights organization Witness.

{9} Ruthie Ginsburg, “Emancipation and Collaboration: A Critical Examination of Human Rights Video Advocacy,” Theory, Culture & Society (September 2019) (link).

{10} See Pew Research, “Key Trends in Social and Digital News Media” (link).

{11} Ariella Azoulay, “The Execution Portrait,” in Geoffrey Batchen, Mick Gidley, Nancy K. Miller, and Jay Prosser, eds., Picturing Atrocity: Reading Photographs in Crisis (London: Reaktion Books, 2012), 251.

{12} These included videos posted by the Israeli Army Spokesman, Yeshiva World News, and more.

{13} Hall uses the phrase “oppositional reading’ In Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse (Birmingham: Centre for mass communication research, 1973).

{14} Hall refers to a “preferred reading.”

{15} See Active Voice Lab, “Beyond the Choir” (link).

{16} To read more about what makes the filming of this kind of event possible, see Ristovska and Price.

{17} Azoulay, “Execution Portrait,” 250-251.

{18} 0404 News is an independent news website promoting a highly nationalistic anti-Palestinian agenda (link).

{19} Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography. (New York: Zone Books, 2014): 93.

{20} Ariella Azoulay, Civil Imagination: a Political Ontology of Photography (London: Verso Books, 2015): 117.

{21} Ibid.