Life, Film, and Decolonial Struggle

Nitasha Dhillon

The domain of the Strange, the Marvelous and the Fantastic, a domain scorned by people of certain inclinations. Here is the freed image, dazzling and beautiful, with a beauty that could not be more unexpected and overwhelming. Here are the poet, the painter, and the artist, presiding over the metamorphoses and the inversions of the world under the sign of hallucinations and madness.

– Suzanne Cesaire

In this text, I address the relationship between my film practice and my work as an artist-organizer with Decolonize This Place. A decolonial practice does not separate artist and organizer. It intentionally blurs the line between the two.

In 2010, I began to articulate such a practice with Amin Husain as MTL Collective. The process of research and organizing, action and aesthetics, debriefing and analysis—as a whole—came to constitute the art practice. This is a process that involves learning by doing in an uncertain terrain of struggle so that we expand the space of imagination, possibility, and training in the practice of freedom. We constantly move with actions and engage with new relations, lessons, analyses, and better questions. Among those questions are the relation between art, organizing, and state violence, in Palestine, the United States, and beyond.

Similarly, decolonial film is not made in isolation from movements and organizing but rather emerges—analytically, aesthetically, and economically—within and alongside movements and against the set rhythms of colonial logic. It holds space, facilitates finding each other, and disseminates ways of making connections across struggles without losing the specificity of each. It unsettles structures and people while taking aim at domination and oppression. It works to undo what we have come to believe are fundamental and unquestionable realities so that we can move differently, together and separately but in agreement, towards decolonial freedom.

Figure 1. Decolonize this Place’s “Reparations/Repatriation Now!” action at the Brooklyn Museum, November, 2018. Image courtesy of MTL+.

Figure 1. Decolonize this Place’s “Reparations/Repatriation Now!” action at the Brooklyn Museum, November, 2018. Image courtesy of MTL+.

Such filmic practice is beyond praxis. With a shifted geopolitical frame for decolonization beyond the nation-state, our ethos in both organizing and filmmaking is that our aesthetics are accountable to communities in struggle. It is cogenerated through informal processes and dialogue. Questions include: what time is it on the clock of the world? What strategies and tactics are needed or being contemplated? How can the frame around a subject be broken in order to ask better questions? What would family and friends watch? How could they be propelled to act? How can film generally, including documentary film, be not about showing and telling but about building, breathing, and living as deeply political acts of resistance, sabotage, and possibility? How can we reorient to one another as a revolutionary act? How can the project of building power be accompanied by the rearrangement of desire? How can we move from a pain-driven to a desire-driven mode of working?{1}

MTL Collective’s feature film Unsettling (forthcoming, 2020) exemplifies a practice that is embedded in a decolonial struggle in relation to Palestine. I evoke the film largely through a series of still images and I frequently cite texts of mine written during the film’s production process. Together, what follows is an account of the different processes in motion at every level of making Unsettling.

****

Decolonization and Decolonize This Place

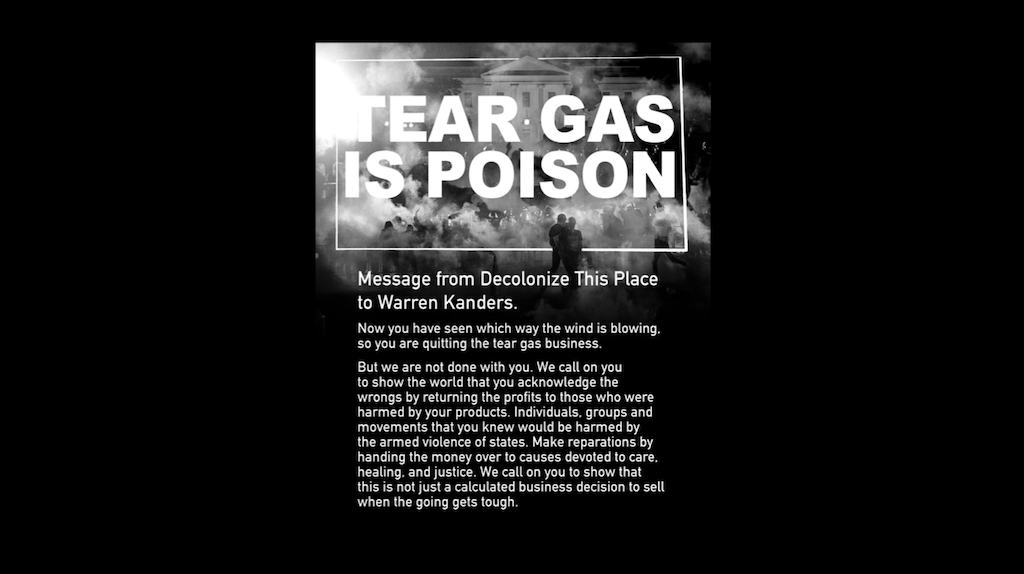

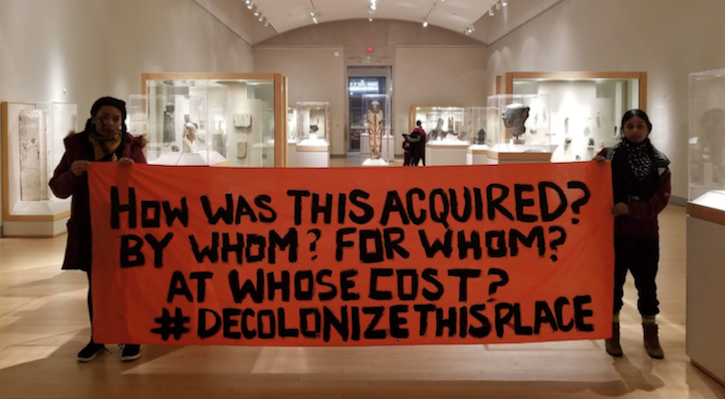

Decolonize This Place is best known for our mobilizations around museums like the American Museum of Natural History, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Whitney, where a coalition of dozens of community groups succeeded in forcing the ouster of teargas CEO Warren Kanders in 2019.{2} These campaigns and actions have received extensive media coverage over the past four years, but something that has consistently been ignored in such coverage is that when we invoke decolonization, we are not using it as a metaphor or codeword for diversity. Rather, we are looking to generations of struggle against settler colonialism and racial capitalism. Aman Sium, Chandni Desai, and Eric Ritskes frame the difference this way: “the mental, spiritual and emotional toll that colonization still exacts is neither fictive nor less important than the material; but without grounding land, water, and air as central, decolonization is a shell game.” We cannot decolonize without recognizing the primacy of land and Indigenous sovereignty over that land. Hence, with indigenous peoples’ struggle, land is central to any decolonial movement and related practices, an important consideration in terms of constructing decolonial solidarity.

Based on the above analysis, Decolonize This Place would later organize and build a decolonial formation in New York City, bringing together related struggles without essentializing them as a way to build power from below. As part of this effort, groups have succeeded in bringing decolonization and abolition together in organizing spaces. For example, groups have sought to center land in all organizing. They are building out the statement often repeated in movement circles in New York City, Stolen Bodies on Stolen Land, and the strategies that follow from that statement. In other words, how does one understand the demand of reparations for enslavement alongside the demand for restitution of land to Indigenous people?

Figure 2. Decolonize this Place’s 4th Annual Anti-Columbus Day tour, Central Park, October 14, 2020. Image courtesy of MTL+

Figure 2. Decolonize this Place’s 4th Annual Anti-Columbus Day tour, Central Park, October 14, 2020. Image courtesy of MTL+

This has led to growing consensus among Indigenous and Black organizers that decolonization necessitates abolition. Abolition as in the treatment of the underlying causes that give rise to the need for borders, bosses, and prisons. As Fred Moten and Stefano Harney put it, “What is, so to speak, the object of abolition? Not so much the abolition of prisons but the abolition of a society that could have prisons, that could have slavery, that could have the wage, and therefore not abolition as the elimination of anything but abolition as the founding of a new society.”{3}

The George Floyd uprising of 2020 has brought this linkage between abolition and decolonization into widespread visibility. Like Standing Rock and the Ferguson uprising it has yet again demonstrated the incapacity of the US nation-state to manage its own contradictions and crises. This has been powerfully symbolized by the burning of police cars and toppling of monuments to white supremacy, settler colonialism, and heteropatriarchy, telegraphed in a banner by Indigenous Kinship Collective reading “No Cops on Stolen Land.”

This moment of becoming ungovernable in the United States is something for which people have imagined and trained for years, with thousands others in the United States and beyond, and we have always had Palestine as a horizon for understanding the possibilities and limitations of resistance here. Over the past decade, the making of our film Unsettling has been a crucial vehicle through which we have tested out forms, mapped power, and built enduring relations over time on the path of decolonization.

In this process of thinking through decolonial film, we have looked to classics of Third Cinema like Battle of Algiers (1966), La Hora de los Hornos (Hour of the Furnaces, 1968), and Leila and the Wolves (1984), as well as Fourth Cinema, with films such as The Nouba of the Women of Mont Chenoua (1977). But decolonial film’s task and role are necessarily different today, because it seeks to advance anti-colonial struggle and decolonial freedom while recognizing that (a) the nation-state and independence are not synonymous with self-determination, (b) the state is no longer imagined as the vehicle of emancipation to the extent that was ever the case, and (c) there is no competing ideology to be scaled up to compete with the global nature of capitalism in organizing socio-political and economic life.

****

Preliminary Notes on Unsettling

Unsettling takes viewers on a journey to Palestine, a land frequently invoked yet rarely heard or seen beyond the distorted representations of mainstream media and pain-driven documentaries. Unlike other films that take Palestine as their subject, the emphasis of this project is on land, life, and liberation rather than Palestinian oppression and dispossession, which, in any event, is captured unavoidably.

Over its duration, Unsettling maps checkpoints and crossings, graduations and cemeteries, streets and alleys, villages and refugee camps, farms and make-shift markets, demonstrations and funerals, interiors of homes and living rooms, all as sites of resistance and possibility. The camera itself is embedded in open-air prisons and enframed by the boundaries and hierarchies established through barriers, militarization, surveillance, and death. In doing so, we wish to reflect a post-Arab Uprising climate, one which embraces political urgency, anger, and rupture. It rearticulates a moment of possibility that was brought forward by the Arab Uprisings and the disappointment, destruction, and fear that followed. It attempts to learn from the failures and brings forward an analysis that reorients our struggles and desires. Its aesthetic mode distills the analysis into a filmic language of affect by looking and looking differently at the architecture of oppression. The piling on of seemingly disparate everyday non-event experiences across a Palestine marked by settler colonialism, military occupation, and neoliberalism produces a call to action that is anti-colonial in its horizon, one that many dispossessed people across the globe relate to beyond the frame of the nation-state.

****

Research, Practice, and Process

We began working on the film that would become Unsettling in 2010. During the first research trip to Palestine, Amin and I traced his memories of the 1987 Palestinian Uprising. We travelled the length and breadth of the West Bank, documenting, witnessing, and researching the architecture of the occupation. Land, life, and liberation were on our mind. We were asking ourselves: when Palestine is so overdetermined by the abundance of media representations, how can one still see and share Palestine?

We learned that Palestinians experience the occupation differently based on where they are located—in the lands of 1948, the West Bank or the Gaza Strip, or if they live in a village, refugee camp, city, or diaspora. We also learned that the sheer presence of a camera or a voice recorder (rather than what is filmed or recorded) is sometimes able to gather people in public, breaking boundaries of alienation and privacy, as workers, for example, respond to questions at a checkpoint, thus creating communal conversations through which people can share knowledge and hear about their own realities.

Part of the way the occupation functions is that one must use the roads permitted, and once you deviate from that path or choose to get lost and document the land along the way, you become a threat to the visuality of settler colonialism that seeks to foreclose imagination and any other possibility.

Just as we prepared to return to New York after a month of listening and learning in Palestine, Mohamed Bouazizi ended his own life through self-immolation in Tunisia, kickstarting the Arab Uprisings. When we arrived back, the city felt and looked different.

Things are buzzing; we are watching closely. Soon Egypt breaks. We see revolutionary people power from below. But it doesn’t seem to apply to the United States, even though we know it is all connected in an expanded field of empire. We say to ourselves, that is a revolution against decades of brutal military dictatorship backed by the US; those are not the same conditions faced by those living in the heart of the empire itself. But then Greece breaks: here is a nominal democracy and yet people are rising up, taking to the streets and holding the squares. Then Spain, a Western nation with an advanced economy in the midst of elections. With the crisis people are compelled to occupy, throwing into question the legitimacy of the entire political process: basta ya! no nos representan.{4}

I wrote a note on representation back then too:

We carry our cameras and our notebooks to document things, but we end up participating. The art we had imagined making for so long is starting to happen in real life. We do not have time to agonize about representation. We are making images, writing texts, having conversations, and developing relationships out of necessity and urgency. Aesthetics, research, organizing; it is all coming together in the creation of a new public space in the heart of the empire. It embodies imagination with implications on the ground.{5}

For many of us, artists and organizers, students and filmmakers, educators and working people, Zuccotti Park was a refuge of sorts and, consequently, an open wound collaged onto the symbolic heart of finance capital. People created self-organized commons and flooded public space with bodies, voices, and cameras, seeking to engage with and involve others as part of an ongoing process of experimentation, learning and undoing, resisting and building in the unexplored terrain of a historic rupture.

Present at the beginning of the Occupy movement, we saw the continuities between organizing against Wall Street and organizing against the settler-colonization of Palestine. We also saw the opportunity to extend solidarity and thinking with Palestine by resisting and building where we are, at the epicenter of finance capital. New York thus became a strategic site of struggle and engagement against ongoing US settler-colonization and, simultaneously remained complicit in materially supporting the continued occupation of Palestinian lands and the ethnic cleansing of its people.

Figure 3. TIDAL: OCCUPY THEORY, OCCUPY STRATEGY, edited by MTL Collective.

Figure 3. TIDAL: OCCUPY THEORY, OCCUPY STRATEGY, edited by MTL Collective.

Occupy built a commons on the financialized terrain of Wall Street, doing so in the name of the populist figure of the 99%. But Wall Street was always already occupied terrain. Lower Manhattan was forcibly seized by European settler colonists in the mid-seventeenth century. Genocide, plunder, dispossession, and enslavement lie at the origins of so-called New York City. Wall Street is named after the literal wall built by enslaved Africans under the command of Dutch and British settler capitalists. The purpose of the wall? To defend the settlement against Indigenous peoples fighting to reclaim their ancestral territories.

As Sandy Grande has stated:

In response to the question provocatively posed by the OWS poster: “What is our one demand?” My answer is: abandon “occupy” and take up “decolonization.” Such a shift would bring the colonial present into sharper relief and, more significantly, allow us to reframe what is happening to workers in Detroit; public school children in Newark, NJ; and, brown, black and poor folks in the nation’s urban centers as not simply about racism, unemployment, outsourcing, downsizing, and privatization—but as removals. A dispossession executed by an elite class still intent on the eliminate-to-replace vision of settler colonialism.{6}

In the end, Occupy may have changed the conversation around wealth inequality (capitalism vs. socialism and communism), but ultimately it failed to change the terms upon which the conversation was being had (capitalism vs. decolonization and abolition). With this lesson, and without losing sight of the walls around Wall Street, we returned to Palestine.

In 2013, on our second trip to Palestine, we broadened the geographies covered. We visited Palestinian and Syrian refugee camps in Jordan and Lebanon. Whereas the first trip we funded ourselves, Creative Time Reports commissioned us to write three articles on our second production trip. We produced three dispatches that same year: “The Slow Sure Death of Palestine,” “Cartography of an Occupation,” and “What is a Refugee if There is no Nation-State?” Each was addressed to those engaged in struggle as a way to learn from and with Palestine.

Figure 4. PALESTINE: CARTOGRAPHY OF AN OCCUPATION, (MTL Collective, 2013).

Figure 4. PALESTINE: CARTOGRAPHY OF AN OCCUPATION, (MTL Collective, 2013).

We spoke of de-exceptionalizing Palestine. With this phrase, we intended to clarify that, without losing the specificity of struggle, Palestine is not an outlying place of intractable conflict but rather an example and harbinger of broader dialectics of oppression and struggle in the world at large. As we put it during our 2013 trip:

We return to Palestine not simply as a personal preoccupation but to use its situation as a compass directing our understanding of other experiences. Why is Palestine so resonant? The entire Middle East and the world’s powerless live under varying forms of occupation. Some are refugees; others are seeking refuge from being a refugee. Palestinians are not living in a “state of exception.”{7}

It is, rather, a prefigurative state. What life has been like for Palestinians since 1948 is what it is becoming for so many in the region and in the world.

As we unpack the term refugee, we should also ask what its converse, citizen, really means. Where and what is Syria? What is Palestine? Before Hassan Hassan, a Palestinian refugee, was tortured to death by the Syrian regime, he said, “all that I know is Palestine is the refugee camp, and the camp is part and parcel of Palestine.”

****

Experimentation, Conversation, and Relations of Care

The research work in Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, and New York established bridges between the movements, shortening the distance created deliberately through the colonizer’s classification. We rejected the colonial borders and the fragmenting of Palestinians across several neighboring states and deliberately chose to use the privilege of movement to stitch together a reality and set of Palestinian experiences that is not meant to happen. We shared what we observed in villages in the north of Palestine with refugee camps in the south. We Skyped with people in Gaza about their conditions alongside people we were conversing with in Ramallah. When we went to Lebanon, we did the same, making connections and drawing comparisons and contrasts between camps in Jordan and Palestine. The idea again was not to render experiences coherent but rather accentuate the similarities and differences as a basis for conversation, living archives, knowledge-making, and solidarity, so that we can get at a deeper texture of what liberation requires. These were the bridges we made in the name of research to make Unsettling.

It was on the basis of this intellectual analysis and aesthetic experimentation with different image formats that we realized we needed to make a film to weave it all together in an integrated flow of time, sound, and image. But what kind of film could be adequate for approaching Palestine, a place composed of a fragmented geography and whose images have been overdetermined by demonizing racism, on the one hand, and cliches of victimhood and heroism on the other?

Figure 5. UNSETTLING (MTL Collective, forthcoming).

Figure 5. UNSETTLING (MTL Collective, forthcoming).

Given that film was a new medium for us at that point, we sought the advice of several experienced film professionals in New York. We intuited that a nonlinear approach would make the most sense and would generate the best questions, but our collaborators insisted that a character-driven documentary would be the most compelling for a transnational audience. We decided to center the arc of the documentary around my collaborator Amin and his complex relation to Palestine as someone who grew up there during the Intifada of 1987, but had then been educated in the United States, eventually becoming an organizer in Occupy Wall Street and beyond.

Even though the concept was grounded in the lived experience of Amin, we found ourselves replicating a kind of ethnographic gaze, soliciting testimony of violence, delving into the psychology of individual people, and overall using pain and trauma as the guiding motor of the film. This felt wrong to us ethically and formally, forcing the reality of Palestine into forms that were both aesthetically mundane and politically disempowering. So for our next production trip we moved away from character-driven production in favor of facilitating movement conversations about life, land, and aspirations of liberation with Palestinians. This was a collaboration process that relied on unscripted dialogue and open-ended questions that allowed for communal conversations, and sharing and learning from one another. These conversations were documented and recorded. Additionally, we attended various everyday events in different parts of Palestine based on personal relations and friendships. Despite collecting a lot of footage, when we went into the editing room, we realized that the footage that we had only permitted the making of an observational film. As a consequence, the political spirit of the film had been neutralized. We consulted with friends, curators, and artists within the field, who told us that we were not saying or showing anything new when seen against the backdrop of contemporary Palestinian filmmaking.

This discomfort with our work thus far led us to the realization that the film would need to avoid any attempt to represent Palestine or Palestinians, and that for it to feel good to us, the film would need to be driven by desire, not pain. How, if at all, could a film articulate solidarity rather than stake its claim on representation? And what would this look like at the level not just of content but at the level of form and the aesthetics of the cinematic image? Most of all, how could the film advance the struggle for Palestinian liberation and decolonial freedom?

Though frustrated that we had invested so much time and work in pursuing the dead-end of a character-driven/observational film, our intensive research trip had generated a rich set of materials. In fact, we had spent as much time gathering atmospheric footage, landscape shots, and audio recordings, all originally conceived as elements to function as background for the plot. What would happen if we flipped the script, foregrounding the background—land, water, sky, city—and eliminating any traditional idea of character or narrative? Here the original intuition that a nonlinear structure would make the most sense returned to us, and we began to reexamine the cartographic collages from our Creative Time projects.

But how could a nonlinear structure and ambient imaginary facilitate the question of solidarity we knew that we needed to confront? These were the questions we were determined to address for our next trip to Palestine in late 2015 in the midst of an Al-Aqsa Intifada; this trip was thwarted however when Amin was detained for 17 hours in Tel Aviv airport and deported back to the United States as a security risk.

Over 200 Palestinians, mainly youth, were killed by Israel during a few months’ time during the Al-Aqsa Intifada. One of the names of those killed was Bahaa Alayan, who wrote his own will in ten points that reflect the sentiment of a new generation of Palestinians resisting oppression:

(1) I urge the factions to not adopt my martyrdom, for my death is for the homeland and not for you; (2) I do not want posters or t-shirts, for my memory will not be merely a poster to be hung on walls; (3) I ask that you take care for my mother, and don’t tire her with your questions whose only purpose is to garner sympathy from viewers and nothing more; (4) Do not sow hatred in my son’s heart, but rather allow him to discover his homeland and die for his homeland and not to avenge my death; (5) If they wants to demolish my house, then let them. The stone is not more precious than my soul which God created; (6) Do not be sad for my death; be sad for what will happen to you after my death; (7) Do not search for what I have written before my martyrdom, search for the reasons behind my martyrdom; (8) Do not chant during my funeral and be impulsive, but rather be on Wudu’ during prayer at my funeral and nothing more; (9) Do not make me to a number that you count today and forget tomorrow; and, finally, (10) See you in heaven.{8}

In early 2016, in the immediate aftermath of that intifada, we were able to return to Palestine using funding siphoned through the academic undercommons by Andrew Ross and Jasbir K. Puar. They accompanied us to Palestine as part of their own research projects. With Ross, we facilitated his research into the conditions of Palestinian migrant workers, eventually taking the form of his book Stone Men: The Palestinians Who Built Israel. In travelling to work sites and checkpoints, meeting workers and learning the history of the land, we ourselves developed new relations to people and places in Palestine. We collected footage throughout the process. We sought to understand the spaces of the checkpoint as not only sites of surveillance and control by the occupier, but rather as sites of social reproduction, organizing, and resistance. This was the first manifestation of how the camera can be used to better see/see differently rather than represent. The key to this reorientation was the use of the camera framing and long duration to generate another relationship with Palestinian reality under occupation, and to open up the meaning in the images coming out of Palestine.

For her part, Puar was researching the right to maim claimed by the Israeli state, which can be understood as the strategic creation of physical and psychological debility and incapacitation among Palestinians along gendered, biopolitical lines. We would travel from refugee camp to refugee camp and learn about people’s experience of the occupation. We filmed the road to get there, the locations, the people, and the conversations as we listened. In her postscript “Treatment without Checkpoints” in The Right To Maim, Puar shares some of her own reflections on the field work conducted in the course of making the film:

Everywhere we went, we heard stories of debilitation: injured Palestinians dying while being transported through twisty back roads to avoid Israeli checkpoints en route to the hospital; men with shattered knees and other multiple permanently debilitating injuries, marking each intifada; ordinary families who had lost one, two, sometime three sons to clashes with the IDF; women who had also been injured or killed; frightened parents worried that children, both boys and girls, were being targeted on playgrounds and in the streets of the camps; speculation regarding policies of shooting to kill and shooting to maim and when and why the IDF might switch between them. There was never a day without terrible news, without some kind of antagonism with IDF soldiers (teargas, shooting, harassment, surveillance), without some confirmed or soon-to-be-confirmed report of shootings of Palestinians, what were often referred to as field assassinations.{9}

The richness of having time together to process the conversations each evening was invaluable for the film and how we continued to develop its filmic language. Conversely, our conversations enriched the rigorous and scholarly research as a contribution to Palestinian solidarity and disability studies and activism. More importantly, the roles of filmmaker and scholar blurred, and participation became part of being present and doing the community-based research. To this point, Puar was present with me when we were invited to film the funeral of a martyr in Sa’ir, bearing witness to and in some ways participating in the gendered division of labor that places women in the role of reproductive emotional and affective labor vis-a-vis the wounded and murdered men of the resistance movement, something would become a major theme in Unsettling.

****

Movement-Generated Aesthetic and Filmic Practices

When we returned to New York from Palestine in spring 2016, we began to develop an explicitly decolonial framework for our organizing of the kind elaborated in the introduction to this paper. Weaving together various strands of decolonial struggle, including Indigenous resurgence, Black liberation, a free Palestine, de-gentrification, the dismantling of patriarchy, and movements of global wage workers, the project has

cultivated a widely recognized organizational, performative, and mediatic repertoire targeting major museums as platforms for the amplification of movement demands and pedagogy. As we have outlined in essays for October and Hyperallergic, this work took us from the Brooklyn Museum to Artists Space, to the American Museum of Natural History, and ultimately into the city at large with the work of the FTP (Fuck the Police) formation in the months prior to the George Floyd uprising.{10} Here, I want to highlight how our work on Palestine inflected one aspect of this decolonial organizing in particular, namely the campaign around Warren Kanders at the Whitney, and conversely, how such organizing informed the making of aestheic considerations of Unsettling.

Above, I explained the logic of de-exceptionalizing Palestine. This analysis has been powerfully resonant in the latest phase of our work with Decolonize This Place targeting the Whitney Museum. In late 2018, a campaign was launched to remove Warren Kanders from the board of the museum. Kanders was at that time the CEO of Safariland, a manufacturer of law enforcement products including tear gas used against refugee families at the US/Mexico border, as well as demonstrators in places like Ferguson, Standing Rock, Egypt, and indeed Gaza.

One reason that Kanders initially became a lightning rod was that the revelation of his presence on the board coincided with the flood of global media images of refugee families and children being tear-gassed at the border. Like pictures of suffering and dead migrants in the Mediterranean Sea, these images were often used to elicit empathy and concern from an implicitly white northern audience aghast at this abuse of human rights, packaging their suffering in ways largely channeled toward liberal anti-Trump outrage.

Deconstructing such images—and the dominant framing and circulation of them through the lens of human rights—was a crucial starting point for how we approached the Whitney. We pointedly refused to use images of people as passive objects of empathy, and instead worked to generate new actions and images of struggle against the forces crystallized by Kanders in collaboration with thirty grassroots groups in the city. These ranged from groups like Arts Space Sanctuary to Take Back the Bronx to Within Our Lifetime – United for Palestine, a longstanding Palestinian solidarity group in New York City.

The purview of Safariland’s violence can be read as a global geography of counterinsurgency against migrants, refugees, and those rendered disposable by settler colonial, imperialist, and racist regimes. Thus, in our approach to pressuring the Whitney to remove Kanders, Palestine was a crucial frame. Rather than treating the removal of Kanders as an end in and of itself, we saw the campaign as a platform for amplifying and linking specific struggles in an expanded work of decolonial movement-building. The backbone of the campaign was “Nine Weeks of Art and Action” over the course of the Spring, with each week bottom-lined by a different group or cluster.

On April 19th 2019, Within Our Lifetime – United for Palestine took the leading role, transforming the lobby of the Whitney into a militant yet joyous tribute to Palestinian martyrs, replete with a debka performance. Further, on the culminating day of the campaign, when we marched from the Whitney to the home of Kanders himself, numerous marchers wore Palestinian scarves to conceal their identities and to highlight solidarity with Palestine. Thus, Palestine was a generalized horizon for the entire campaign, rather than a siloed issue. Over the course of this work, there was never any question of representing Palestine in either an aesthetic or political sense. Palestine was woven into the core of the movement and assumed as a baseline commitment for all participants.

Kanders would ultimately be forced off the board in July 2019, creating a massive crisis of confidence and legitimacy among the elite world of cultural funding and governance, including at places like the Ford Foundation that have been involved in the funding of contemporary art, scholarship, and political organizing alike. But though he was no longer able to participate in artwashing via the Whitney, Kanders’ own personal and corporate power remained intact beyond the art system.

Though the Whitney campaign is not featured in Unsettling itself, it embodies a similar ethos: we began by refusing the default mode of the journalistic image of suffering, and instead worked to create space for action, thought, and images. Indeed, now, when one googles Warren Kanders, what appears is not just him at a gala, or isolated pictures of the suffering his company has inflicted, but also images of people from a wide range of struggles using the platform of the Whitney to stand in solidarity with each other, linking struggles against the camps at the border with those in Gaza, people fighting displacement in the Bronx with those fighting disaster capitalism in Puerto Rico.

****

The Martyr Scene

I now wish to share some reflections and important facts from filming the funeral in Unsettling. First, as we were invited to join in mourning the loss of four young men—three of them cousins who were all in their twenties when they were gunned down by Israeli soldiers as they entered their village. I found myself placed into the role of the documentarian who must reflect the pain and harm being experienced by the oppressed to the world. The underlying assumption here is that if the mother’s loss is shown, and if the community’s pain is seen, people will act against injustice. As a filmmaker, I found myself performing that role offered to me as they made way for me to film the bodies being kept company in the ambulance by their loved ones.

Figure 7. UNSETTLING (MTL Collective, USA, forthcoming, 2020)

Figure 7. UNSETTLING (MTL Collective, USA, forthcoming, 2020)

As part of the care we had to show, we demonstrated that they were being heard and seen, even though these are not the images we intended to film. In other words, and later in conversations with Puar who removed herself after some time because of the overwhelming sense of pain, I acknowledged the pressure to perform the role of a documentarian who must give meaning to senseless, unjust loss, as a sign of respect. As such, I filmed martyrdom in the ways that allows for the gaze to consume loss, and contributed to the oversaturated field of images of the martyr with little specificity and little room for healing, resistance, or desire, despite knowing that there is another way to understand martyrs and their offering of love as Bahaa Alyaan expressed in his will.

The two angles brought by Ross and Puar to the trip—framing the Palestinian proletariat that builds the infrastructure of Israel and its associated economies, systems, and spaces of labor control, and women’s reproductive labor under conditions of state violence—brought a new degree of economic, political, and cultural specificity to the cinematic-cartographic challenge of articulating solidarity at the level of form and content. With migrant labor, we were able to complicate the monolithic icon of the wall that features in so much coverage of Palestine, noting instead the multiple ways in which the occupation is practiced and deployed so as to modulate and control populations on a flexible basis; and in our experience of the funeral and the martyrdom work of the women we met, we confronted once again the problem of pain-driven narratives, but now among the people on the ground rather than through external coverage; how might the narrative of the martyr be liberated from patriarchal conceptions of heroism and sacrifice, and the attendant gendered roles that in turn requires? As movement scholar Hadeel Badarneh puts it in an article published in our magazine Anemones, the IDF has developed an entire tactical logic wherein centralizing, targeting, and attacking male activists serves to not only erase women’s leadership, but also to create vast amounts of additional and exhausting reproductive labor for women when it comes to defending and caring for decapacitated or incarcerated sons, brothers, husbands, and comrades.{11} Put differently, the tactics used by Israel intentionally contribute to creating and sustaining a masculine resistance movement that enacts traditional gender roles and views of sexuality as a way to preserve a national identity and resist annihilation. More specifically, in considering the figure of the martyr, this form of counterinsurgency by default forces men into internalizing a damaging ideal of the war-like hero or the sacrificial martyr that is ultimately disempowering for the movement as a whole, making the promise of liberation more distant and the struggle more vulnerable.

****

Desire Not Pain

Refusing a pain-driven model of documentary that fetishizes trauma and relies on victimization narratives, Unsettling is a desire-driven experimental film. It builds a space and time wherein the genres of documentary and fiction allow for old questions to be asked again. It aims to rearrange the desires, relationships, and imaginations of its collaborators and its audience through both its aesthetic form and its processes of production and distribution. It is rooted in the ever present questions of home, nation-state making, modernity, and patriarchy, as they relate to liberation struggles and movements. Desire-driven models of culture making attend to what is lost by failing to interrogate the frame. By pursuing desire, the work comes to ask questions that refer to pain but are not beholden to it. The pain is the background upon which better questions come to be asked. In the context of the film, the image does not represent a condition as much as look at a condition through the lens of the camera in order to understand it, because if we can understand it better perhaps we can change it, and that is how the audience comes to be invited into a specific kind of space that is action-oriented.

David Graeber visited Palestine with us in 2015 during one of our production trips for the film. Shortly after we returned, David wrote this insightful piece which reflects his brilliance. David was one of the real ones who left too soon. We miss him dearly.

Background Video: Unsettling (MTL Collective, 2020)

{1} Eve Tuck and K.W. Yang, “R-Words: Refusing Research,” in Humanizing Research: Decolonizing Qualitative Inquiry with Youth and Communities, eds. Django Paris and Maisha T. Winn (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2013).

{2} See Nitasha Dhillon, “On Decolonize This Place,” Artleaks Gazette 5 (April 2019); MTL, “From Institutional Critique to Institutional Liberation: A Decolonial Perspective on The Crises of Contemporary Art,” October 165 (Summer 2018); and Decolonize This Place, “After Kanders, Decolonization is The Way Forward,” Hyperallergic, July 30, 2019.

{3} Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Wivenhoe, NY: Minor Compositions, 2013).

{4} MTL, “Occupy Wall Street: A Possible Story,” in Global Activism: Art and Conflict in the 21st Century, ed. Peter Weibel (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015).

{5} Ibid.

{6} Sandy Grande, “Accumulation of the Primitive: The Limits of Liberalism and the Politics of Occupy Wall Street,” Settler Colonial Studies 3 (Fall 2013): 369-380.

{7} MTL Collective, “What Is a Refugee If There Is No Nation-State?,” Creative Time Reports, February 3, 2014.

{8} Maureen Clare Murphy, “How a Scout Leader Became a Martyr,” The Electronic Intifada, February 12, 2017.

{9} Jasbir K. Puar, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).

{10} See MTL, “From Institutional Critique to Institutional Liberation?,” and “The Arts of Escalation: Becoming Ungovernable on a Day of City-Wide Transit Action,” Hyperallergic, July 31, 2020.

{11} Hadeel Bardaneh, “Patriarchy, Counterinsurgency, and the Palestinian Struggle,” Anemones (August 2018).