Ways of Organizing: Against Convergence

Rasha Salti

I would like to preface my answers by noting that programming, like curating, is essentially a form of production of knowledge, experiential and poetic. In many ways, it is contingent on several factors, the host institution’s mandate, local sociocultural and political conditions, audience, resources, and technical screening conditions. There are also other considerations, which you point to in your introduction, namely the current state of film distribution and exhibition worldwide, the commerce of theatrical release. Until the 1980s, and sometimes even the 1990s, there were film screening facilities in town halls and union halls in European towns and cities. Several cinemas were still operational in African capitals. And film screenings were part of the extracurricular school programs. Film-going was a lot less of a class-segregated activity, film was an integral part of the experience of culture. Furthermore, I come from a part of the world where political, cultural, and artistic dissent have narrow margins of tolerance, where the fabrication of documentary films is far more tightly “policed” than other genres, and where the exhibition of dissenting films is casually prohibited and can constitute an overt act of defiance against the regime or a hegemonic political force. Last but not least, the distinction between “documentary” and “fiction” is increasingly disregarded by film festivals. I could cite a long list to corroborate this point, but two will suffice, the Festival International du Documentaire (FID) in Marseille, has long discarded such distinctions, as has the Berlinale’s Forum. Especially when discussing “convergences” between categories and genres that dwell in hybridizing, or expanding form, delineating the “documentary,” nonfictional and fictional, is not only odd but also pointless. Going back to the question of programming, it is very hard to answer your questions with precision, because the impetus for programming corresponds to radically different urgencies in different places.

MAPPING SUBJECTIVITY: EXPERIMENTATION IN ARAB CINEMA FROM THE 1960S TO NOW, Museum of Moving Art (2010)

MAPPING SUBJECTIVITY: EXPERIMENTATION IN ARAB CINEMA FROM THE 1960S TO NOW, Museum of Moving Art (2010)

Technically, the convergences of documentary with conceptual video and performance art practices are as recent as the emergence of video technologies and of the formal recognition of the categories of conceptual and performance art as genres in art. In fact, if the reference is to experimentation in film language, then these convergences predate them. If the reference is to practicing visual and plastic artists making films, then these convergences predate them. Moreover, there have been film festivals dedicated to experimental cinema (that uses celluloid and video) since the 1960s. What I might identify as a convergence is the fact of A-list film festivals, deemed “canonical” for the industry and market, imparting programming space, dedicating staff and resources, to showcase what is widely known as “expanded cinema.” Often the ambiguity of the use of “recent” has inspired me to investigate, look back and try to understand an unwritten recent past. Such was the impetus behind the project “Mapping Subjectivity: Experimentation in Arab Cinema from the 1960s to Now,” that was presented at MoMA in three editions between 2010 and 2012. But perhaps I digress. If your question is why would the Berlinale’s Forum section institute a Forum Expanded section, or the Toronto International Film Festival a Wavelengths section, or perhaps, more recently, the Venice Film Festival a Biennale Cinema College program? From a programmer’s point of view, the answers are multiple. Intuitively, the first one would be, because expanded cinema is more prolific than ever before, and continues to be so. Part of a film festival’s mission is to be a sort of “vitrine” of what is new in film, in the world, the volume of expanded films beckoned to be engaged with. This is certainly where programmers played an important role, in communicating to a festival’s administration the necessity to adapt a festival’s structure to engage with a cinematic production that eludes criteria for enlisting in existing sections. Jean-Luc Godard said, “c’est la marge qui tient la page,” or, to translate quickly, it is the margin that holds the page, namely, if you consider what was deemed “marginal” or “experimental” thirty, twenty, or even ten years ago, you realize how quickly deconstructing narrative structure, or relationships between image and sound have become part of more mainstream documentary cinema. In other words, expanded cinema is a terrain for the renewal of film language generally, thus its vitality, and is certainly one of the strong arguments programmers used to lobby with festival administrators to institute a change in the overall structure of their event.

Secondly, and definitely more cynically, the world of contemporary art is far more wealthy than the world of cinema. As expanded cinema is more often than not the work of practicing artists, this convergence is also a rapprochement to a different economic order. When artists make films, often they fabricate them outside the economic regime that regulates film production and exhibition, which in many ways can be regarded as a form of emancipation from a system that has been mired in crisis for a while. Surely their budgets are usually a lot less heavy to levy, but their public release and trade are very different.

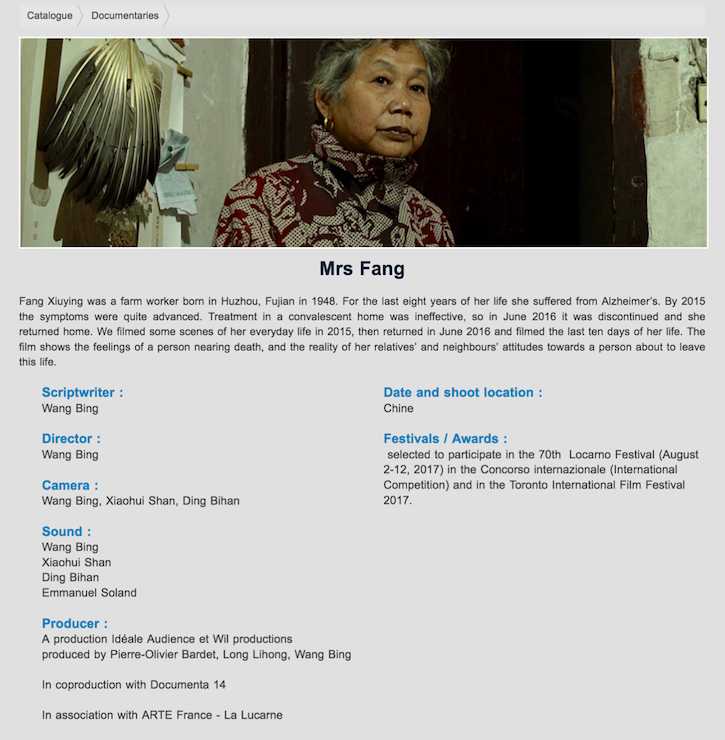

Celebrated Chinese director Wang Bing’s most recent “documentary,” Mrs. Fang (2017) is an interesting case in point. It was funded by Galerie Chantal Crousel (his gallery in Paris) and by ARTE France Cinéma (the French-German television network). It premiered at the Locarno International Film Festival in August 2017, and has been touring festivals since. It was broadcast on television in November 2017, and will soon have its theatrical release in several countries in Europe. It is also an “object” of the gallery’s catalogue. Editions of the film can be acquired by cinémathèques, film archives, museums of art, and private collectors through the gallery. And the rights for theatrical release have been sold by the film’s main producer, I imagine that VOD and DVD release will also be negotiated by both gallery and producer. Wang Bing is a filmmaker, not a practicing contemporary artist, however, his case evidences that the world of contemporary art has dwelled comfortably enough in the world of expanded film that it can venture further into the world of auteur film. In fact, FID Marseille’s “FID Lab,” or the works-in-progress co-production, three-day convention, has been soliciting museum curators, galleries, and collectors as much as protagonists from the film world from its beginning.

MRS. FANG (2017), courtesy of ideale-audience.com

MRS. FANG (2017), courtesy of ideale-audience.com

Digital technologies, video or beyond, have proliferated the production of moving image works, and at the same time, the drastic (if not extreme) collapse of conventional film exhibition spaces have pushed filmmakers and artists—moving image makers—to find new spaces for making and showing films. This is a worldwide phenomenon. Film programmers, certainly myself included, whether attached to festivals or not, have been acutely aware of this change and felt the urgency, necessity, and desire to commend existing “vitrines” to adapt.

The social movements that have taken place in the past ten years, such as the Arab Spring, or, prior to that, the 2009 Green Revolution in Iran, and the uprising in Ukraine, produced suddenly a huge volume of moving image material that ranges between citizen journalism, forensic evidence, and amateur archives. These documents are not “cinema” in and of themselves. Concretely, they are made from the raw material from which cinema is made, but also from the mental disposition of the person behind the camera and whoever is being filmed. First and foremost, they are a challenge to media archivists: what indexes should be innovated to organize them, especially in times of conflict, when wars are also waged using moving images, authors are “everyday folk,” their dissemination on the Internet is contingent on the “invisible” forces that hold the keys to the algorithms, and their viewership is also quantified by algorithms and qualified by “expert” interpretation. Citizen journalism and its dangerous flirtation with political propaganda is one form of embodiment of today’s discussions on journalism, fake news, and “post-truth” media.

There are shelves of books that study and theorize how ethnographic and amateur cinema has influenced filmmaking over time. To address our contemporary moment and bring this discussion to a more personal scale, I will recount my experience with the activist videos that surged after the Syrian uprising, in 2011 and 2012. As a film programmer with some knowledge of Syrian cinema, I was solicited by film festivals and other institutions to organize sidebar programs showcasing activist videos and films when the uprising erupted. On the one hand, I was delighted that film festivals deemed important to acknowledge a controversial political where a civilian population was taking tremendous risk, and thus accepted the invitation gladly. On the other hand, I felt a responsibility to “frame” these moving image documents, and rather than screen films, I proposed to deliver lecture-presentations where I was able to historicize dissent in Syria (in film specifically), and provide a holistic context for the insurgents’ iconographic and performative language. The political nature of these insurgencies (namely the Green Revolution in Iran, the Arab Spring, and the Maidan revolt) had similar political features, and to some extent, outcomes. Two films that were made in direct reaction to them stand out as stellar cinematic achievements that I modestly deem as milestones in how contemporary film captures civil war and exile or popular insurgency, respectively. They are Ossama Mohammed’s Silvered Water: Syria Self-Portrait (2014, in the case of the former) and Sergeï Loznitsa’s Maidan (2014, in the case of the latter). They both premiered at Cannes, as part of the official selection, but out of competition. They were screened widely in film festivals, they had a theatrical release in some European countries, but they also continue to screen due to invitations from activist associations, and communities concerned with human rights and solidarity. In other words, they kindle a mobilization in civil society about ongoing tragedies when straightforward political calls to action or engagement are unable to. In addition to being cinematic feats, their interpellative political power is undimmed, far beyond their lives in film festivals or theaters.

Mediation begins with the programmer’s contact with the film itself, its author, producer, writer, cinematographer… Travel is key, and that is where international festivals keep an edge, by allocating generous travel budgets for their programmers to discover films in their locales. Programmers are often assigned large territories and cannot be expected to have expert knowledge of the historical and cultural conditions for each country. I usually packed my travels with screenings, but I also made sure to meet other cultural protagonists, writers, artists, film critics, and distributors to gather as many different points of view as possible, and understand the cultural codes and political stakes of representation and narratives. International programmers have the privileged position of hinging between a locality and an international stage, channeling information, but more importantly translating a poetics to an audience, to film critics, and to an industry. When I was part of the Toronto International Film Festival programming team, I was mandated to selecting films from the African continent and the Arab world, vast territories, complex realities, where the classical structure of a film industry per se exists only in Egypt and South Africa. These two geo-cultural territories shared an interesting feature, namely, they were postcolonial realms. This implies that they remain burdened with all sorts of stereotypical representations and narratives in the collective imaginaries of the “former” Western world. Film is neither a surrogate for news nor a seminar on representation, it is a work of art that is invited to be part of a program, side by side with other works of art from across the world. The chief premise about audience and mediation that I followed as a programmer is the trust that audiences should not receive instructions on how to perceive the film they are about to discover. I gave cues about cultural codes, in the film note published in the festival’s program book, or in interviews, and mostly in the Q&A that followed the screening. The most important thing to mediate are trust, enthusiasm, and a sleight of hand invitation to see beyond stereotypes or preconceived notions of such and such place, story, etc. I often repeat that film is not an alternative to news, journalism, or investigative reporting. It is important when it comes to Arab and African cinema.

With regards to expanded or experimental cinema, the prejudices are about so-called cultural capital and the audience’s ability to decipher metaphor, allegory, and nonlinear narrative. Obviously, the way we tell or remember a story is nonlinear, and poems and song lyrics are all charged with metaphor and allegory when an audience has firmly set expectations of what a film should look like, unravel, or do, I use similar strategies to dissipate preconceived notions. It is not systematically successful, but certainly useful. It’s a mediation that aims at “un-learning” how to apprehend a film, or “un-do” expectations, rather than prescribing or instructing.

Title Video Credit:

The Time That Remains, Omar Suleiman (2009).