Tongueless Whispers and Recited Choreographies

Yasmina Price

Whatever they do, black people talk to each other. They have always done so. The searing vignettes passed on by old sages to youth made memory itself an instrument of survival. Each generation, then, built on the lessons learned by preceding ones.

—Mary Frances Berry and John W. Blassingame, Long Memory: The Black Experience in America

But what specially interests me is the hold of both memory and geography on the desire for conquest and domination.

—Edward Said, “Invention, Memory, and Place”

Forensics and Counterforensics

Evidence does not resolve historical violence, nor does proof put an end to its afterlives.{1} Enslavement and colonization were carried out in the open and have left behind plenty of both. If the permutating structures of exploitation and dispossession that continue to imperil black life could be considered a “crime,” we know whodunit. Conventionally authorized responses to crime—policing, carcerality, the law, and forensic science—are themselves complicit, as are their authoritative claims on objectivity and verification. They carry a false promise of resolution, out of measure with historically rooted and evolving conditions that resist any singular, coherent closure. These forensic mechanisms cannot register or account for the remembrance of how black people have withstood and circumvented a world architecture of predation. While by no means immune to the same predatory systems of global power, counterforensics present another way through by (1) allowing for an ethics of irresolution that upends the illusory, absolute hold of governing laws; and (2) recovering subjectivity and embodiment as the memory discarded, erased, or obstructed in dominant records of violent histories.

Within the aesthetic realm, counterforensics encompass a multidisciplinary range of art practices that challenge the legitimacy of institutional, empirical, and authenticating forensics and displace their terms of evidence and legal regulation. Looking to the audiovisual work of contemporary Afro-diasporic artists Onyeka Igwe, Caroline Déodat, Audrey and Maxime Jean-Baptiste, Christopher Harris, and Languid Hands (Rabz Lansiquot and Imani Mason Jordan) reveals how strategies of witnessing, speculating, and testifying through body and voice can stake out a political intervention. Their aesthetic counterforensics bypass metrics of truth-seeking that are indissociable from colonization and enslavement as they bear upon the present. Crucially, these artists trouble the dubiously assigned task of generating evidence as a naturalized pathway to repair. What has been rendered all too clear in the coexistence of not only unabated but increased anti-black state violence and its real-time recording—with horrifying parallels in the documentation of the presently relentless genocide of Palestinians—is the reality that there is virtually no correlation between evidencing and ending. What is at stake in the work of these artists is not more objective evidence-seeking or even the notion of providing antidotes to the ills of historical violence, but rather the recovery of plural, spectral, and kinetic traces of memory, gestures, sounds, and testimony that have always coexisted as an oppositional form of knowledge and record of life. These counterrecords function as inherited “instruments of survival,” or what Leigh Raiford has termed a critical black memory.{2}

The aesthetic counterforensics of these artists reengineer the meaning, understanding, and transmission of the past. While they all contest forensics secured by evidence and legal regulation bound up in colonial and anti-black hierarchies of life, they do so from distinct macrohistorical contexts and address specific tensions in the matrix of blackness and coloniality, crossing the geographies of Nigeria, Britain, Mauritius, France, French Guiana, the Antilles, and the United States. Without conflating the particularities of these disparate contexts, what links Igwe, Déodat, the Jean-Baptiste siblings, Harris, and Languid Hands are the clear resonances in how their aesthetic counterforensics take form. Through moving image works, they perform body, voice, ritual, and reenactment on an unfixed ground of remembrance, combining this with the tactical manipulation and imaginative supplementation of archival materials. Their works stage the friction between, on the one hand, dominant archives as forensic evidence and, on the other, aesthetic strategies as counterforensic contestation of memory.

These Afro-diasporic artists leverage their practices to scramble the primacy of the visual and facilitate a historical consciousness of the racialized hierarchies embedded in technologized seeing. While the works I have chosen to compare are visual in form, they deny the ideological hegemony of visuality. Nicholas Mirzoeff distinguishes visuality as a mechanism of command that naturalizes its own suturing to power, functioning as “both a medium for the transmission and dissemination of authority, and a means for the mediation of those subject to that authority.”{3} While visuality aligns with forensics and its enforced terms of evidence, what Mirzoeff contrasts as the “right to look [which] claims autonomy, not individualism or voyeurism, but the claim to a political subjectivity and collectivity,” has its corollary in counterforensics and the restoration of black memory.{4} Igwe, Déodat, the Jean-Baptistes, Harris, and Languid Hands channel remembrance through the use of ambivalence, concealment, uncertainty, and multiplicity combined with formal tactics of delay, fragmentation, and repetition. Their approach is compatible with the communal, oppositional aesthetic practices outlined by Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman in their book Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth, in that the artists enact a “careful attunement and noticing” and yield “constructions [wherein] each found element is not a piece of evidence in itself but rather an entry point to find connections with others.”{5} The artists I have gathered all share in this quality of pluralistic, resignifying assemblage. Resisting homogenous singularity and recovering heterogenous multiplicity is essential to the counterforensic function of their experimental films, hybrid documentaries, and speculative moving image imaginaries.

Their common ground can only be understood through the recognition of their distinct contexts. Artist and researcher Onyeka Igwe confronts how historical, archival, and cinematic systems of oppression created through the British Empire’s colonization endure in present-day Nigeria. Interlacing filmic records and gestural vocabularies, her work rereads the past, finding a third way that is neither paralyzed by persisting injuries nor deluded by a fiction of ahistorical overcoming. Igwe’s images toggle between the colony and metropole by way of institutional spaces and a choreographic relay of women’s performances. While sharing Igwe’s focus on moving bodies, scholar and artist Caroline Déodat’s visual works are significantly ecological and deal specifically with Mauritian colonial history. Likewise repurposing cinematic materials, Déodat operates in an archival context that is far barer than that of Nigeria and Britain, which orients her toward the absence and ghostliness of memory, metabolized through dance and nature. Choreography is a pathway for Déodat to analyze how indigenous practices are corralled by the colonial foundations of film and jeopardized by commodification, while simultaneously recognizing their capacity to retain a dissident inheritance. Maxime Jean-Baptiste, a filmmaker and performer, presents a more familial lens, collaborating with his sister Audrey Jean-Baptiste and enlisting his father, Gilbert Jean-Baptiste, in the different Afro-diasporic cartography of French Guiana and France. Choreography is again crucial, but the stakes of these moving images and performative works are especially angled toward the voice and oral storytelling as channels for recovering ancestral narratives. Conjugating Hollywood and slavery in the context of the United States, experimental filmmaker Christopher Harris orchestrates fugitive spatialities in antagonistic relationship to the anti-black colonialist origins of the camera. Materializing an undisciplined black sight, his imaginative reenactments propose a counterhistory of the medium. Finally, the London-based artistic and curatorial duo of Languid Hands assembles a polyvocal text of fragments and testimonies, appropriating a mosaic of footage through the grammar of video art. Within expansive geographical coordinates, their primary targets are the law, surveillance, and state brutality.

Through their audiovisual practices, these Afro-diasporic artists model how aesthetic counterforensics can expose the insufficiencies of evidence and forensics anchored in the authority of dominant colonial and imperial systems, and provide a way to glean an oppositional chronicle of black memory. Importantly, their multisensorial and somatic methods attempt to do so without straightforwardly replicating the representational violence of historical atrocities and contemporary brutalities. Theirs are open-ended practices, which do not yield a final truth any more than they promise full repair. They offer what they enact: a kinetic, pluralistic process of revision that breaks the static hold of colonialist and capitalist inevitability to open other portals between the past and present, to more fully understand how we came to be here and where else we might go.

****

Archives and Machines

The polymorphic practices of Igwe, the Jean-Baptistes, Déodat, Harris, and Languid Hands repurpose archival materials with an understanding that they are neither self-evident nor transparent, and incapable of being delinked from the structures that created them. Their tactics circumvent what forensics would call evidence, and also fundamentally upend, dismiss, and rewrite what that evidence can be taken to do. Several of the artists incorporate archival elements from dominant film cultures—be they American Hollywood films or French colonial ethnographic works—to both challenge and transform how those visual materials act. In demystifying the illusory objectivity that masks asymmetries of power, they challenge the evidence of archives and demonstrate what meanings can be made despite them.{6} As much as they are revelatory, their works are with equal importance ethically occlusive, refusing the seductions of solving a crime with forensic evidence or alleviating hypervisual violence with a purely visual response. By appropriating and subverting colonial archives, these Afro-diasporic artists mobilize the embodied and sonic dimensions of collective, transtemporal witnessing. Their synesthetic audiovisual works resurface a global inheritance of black memory that passes beneath and beside the evidentiary colonial record of history.

Cutting between two defunct spaces—the abandoned building of the Nigerian Film Unit in Lagos and the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum in Bristol—Igwe reexamines the materiality, presentness, and colonially intertwined historical fabric of Nigeria and Britain in the short film a so-called archive (2020). The camera glides in a slow, exploratory survey of ruinous constellations of discarded film reels, surfaces thick and soft with dust, excesses of hoarded objects, cracked walls, melancholically overflowing boxes of documents, and the cavernous emptiness of storage rooms. Igwe’s critical reappraisal of how British imperial and national mythmaking is encoded in a record of recordkeeping destabilizes its assumed power. The challenge indicated in her delightfully insolent title is enacted by undermining the sanctity and coherence hegemonic archives rely on. The overabundant relics of the former Bristol museum lie wasting away as inert evidence of colonial and imperial crimes. Igwe’s aesthetic counterforensics expose the sepulchral hollowness that conditions this hoarding of the past.

Both drawing on and defying her training as an anthropologist, Déodat exercises a similar archival intervention. Her experimental shorts Sous le ciel des fétiches (2023) and Landslides (2020) are spectrally ritualistic and choreographic investigations of remembrance and coloniality on the island of Mauritius. Divided into three loose sections, Sous le ciel employs a metacinematic third act to dispute cinematic archives in relation to the Mauritian séga.{7} Déodat defines the séga—which is at the heart of her aesthetic and scholarly projects—as “a practice of performed poetry and dance born in the 18th century within the contextual violence of the plantation slavery society.”{8} In Sous le ciel, clips taken from an ethnographic film depicting these practices, Ô pauvre Virginie (Louise Weiss, 1963), are projected onto the twirling fabric of a woman’s long white skirt, doubly animated by the dancer’s movements as the image spills onto the wall behind her. The repurposing of Ô pauvre Virginie uses the archival work to mark the mid-twentieth-century shift when the séga was commodified. Turned into a belatedly fabricated signifier for the national Creole heritage, its role as an expression of indigenous autonomy was subjected to colonial capture.{9} These same archival fragments are then projected onto an outdoor cloth screen, accompanied by the sound of nocturnal insects, as a figure appears and sets fire to one corner of the screen. As the fabric rapidly disintegrates, leaving behind an empty, incinerated frame, the projector in the background is revealed. The images appear all the more ghostly, now projected onto wafts of smoke. Sous le ciel performs the literal and symbolic destruction of the visual machinery of colonization. Yet rather than presenting a false fantasy of repair and restitution, there is a lucid caution in Déodat’s counterforensic gesture. Both the screen’s frame and the projector ultimately survive, suggesting that such acts of liberatory arson are not endpoints, but embers of revolt that must be continually stoked.

An evolving video and performance work by the duo behind Languid Hands, Rabz Lansiquot and Imani Mason Jordan, Towards a Black Testimony: Prayer/Protest/Peace (2019) weaves texts, voices, archival footage, and contemporary imagery into a collective portrait of black defiance. Across three acts of a visual and sonic collage, they meditate on the precariousness of black life, mobilizing black witnessing to confront the limitations of law and legibility in testifying to the unseen and the unheard. To achieve shared ends, their aesthetic counterforensics take a different route than what is found in Igwe surveilling British material archives or Déodat repurposing an ethnographic film. Languid Hands sequence archival footage to make visible the continuum between Washington, DC, in 1963, Brixton in 1981, and Ferguson in 2014, to make audible a demand for freedom still unmet. Black women in white hats emblazoned with “Freedom Now!” are followed by black girls with megaphones. By placing the historical episodes of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and the riots and uprisings against racialized police violence and systematic discrimination in the UK and the US, Languid Hands go beyond the forlorn presentation of evidence that black people are brutalized by the state. Rather, they stake a claim on the accumulative memory of confrontation and noncompliance which links these episodes together. At the film’s halfway mark, they turn to yet another archival composition, collaging footage of wedding celebrations, family portraits, and a panoply of Afro-diasporic spiritual and religious practices of worship, dance, and social communion, which establish the remembrance of lifeways that both exceed and encompass direct responses to vulnerability and brutality.

In another Afro-diasporic cartography, Maxime Jean-Baptiste places reenactment at the center of his audiovisual memorywork around the Guyanese and Antillean diasporas in France. His practice is a familial effort, as Écoutez le battement de nos images (2021) was codirected with his sister and fellow filmmaker, Audrey Jean-Baptiste, while Nou voix (2018) and Moune Ô (2022) include the participation of his father, Gilbert Jean-Baptiste. Together they parse a colonial history of starts, stutters, and spasms. Similar to Igwe and Déodat, what is enacted across all three films is a self-reflexive, fugitive counterforensics, as Jean-Baptiste appropriates and manipulates cinematic and scientific materials to reveal their incriminating traces and to dance out of their reach. In Écoutez le battement, Audrey and Maxime Jean-Baptiste apply an aesthetic counterforensic process to audiovisual archival material from the CNES (Centre national d’études spatiales). Their experimental documentary places footage of the creation of a space center in Kourou (a commune in French Guiana) within a fictionalized narration, challenging the project of colonial infrastructure and using it as a foothold to indict the concurrent absenting of the Guyanese population. Key to their counterforensic memorywork is the use of oralized history to modify the evidence of the CNES documents. The narrator of Écoutez le battement, a Guyanese girl performed by actor Rose Martine, delivers an observational chronicle interwoven with her grandfather’s memories.

Trailer for MOUNE Ô (Maxime Jean-Baptiste, 2022).

In both Nou voix and Moune Ô, Jean-Baptiste performs a generative denaturalization of the film Jean Galmot, aventurier (1990), recalling Déodat’s use of Ô pauvre Virginie. Directed by Alain Maline, Jean Galmot follows the template of the unselfconscious and brazenly celebratory explorer-cum-colonizer narrative, telling the story of a French writer and gold prospector in early-twentieth-century French Guiana. Jean-Baptiste appropriates the film in Nou voix, opening his experimental film with clips taken from a courtroom scene in Jean Galmot, with onscreen text explaining how his father was one of fourteen Guyanese chosen as extras to act in the scene as the defendants, called the “insurgés.” Creating a metacinematic joke, their labeling as “insurgents” gestures to how the Jean-Baptistes intervene in the colonial record. Shifting from the colonial film to the events surrounding it, Moune Ô incorporates footage of the paraspectacle of the premiere for Jean Galmot’s release in Paris, which his father had attended. Following the itinerary of Gilbert Jean-Baptiste’s relationship to the 1990 film is a counterforensic investigation that provides a critique of colonial cinema. The provocation is exercised at the formal level. The clip from Jean Galmot in Nou voix appears in a stuttering slow motion, accompanied by a sonic track of forest sounds, while Moune Ô begins with a similar modification of the festive, costumed procession of the film’s premiere, disfiguring the footage and transforming the choreography of the participants. Rupture and slowness create a lexicon of counterforensics that collaborates with reenactment and replay as methods of resignification. Nou voix and Moune Ô resituate the terms of Jean Galmot: The colonial film is presented anew in a way that delegitimizes its authority as a dominant text through the formal subversion of Jean-Baptiste’s coagulating tempo and volcanic editing. Here again, counterforensic aesthetics expose the terms of representational and historical violence in a way that does not pretend these can be erased, but rather demystifies their function and reveals alternative knowledges of the past and of black life.

****

Choreography and Embodiment

As with Nou voix and Moune Ô, so too do Igwe, Harris, Languid Hands, the Jean-Baptistes, and Déodat rely on the body and voice as primary materials. Across their practices, choreography, reenactment, sonic interventions, and oral expression circumvent and contravene the forensics of hard evidence. Sharing in the corporeal and vocal reinscription of Afro-diasporic remembrance, these artists contest colonial chronicles.

The jittery denaturalizations of movement in Jean-Baptiste’s films are a programmatic challenge to colonial coherence and temporality. They find almost exact parallels in Towards a Black Testimony, where formal changes in rhythm are also used as a subversive method. Languid Hands open their video with slow-motion footage of Carnival in Sint Maarten—revelers dancing, sauntering, walking down an open road—which visually mirrors the parade in Moune Ô. Most of the film is in slow motion, creating a shared tempo of protest between the march of 1963 and the uprising of 2014 in particular. Yet there are differences between Towards a Black Testimony and Jean-Baptiste’s works. Rather than being used as a tactic to unsettle a dominant evidentiary record, here the slowed-down footage links and dilates episodes of rebellion. The counterforensic aesthetics of black memory are rendered as a reminder of what continues to be fought against, over and across different histories and geographies. Along with stutters and repetitions, these modifications of the archival footage make room to absorb how the gestures and choreographies of walking slip into those of dancing, how revelry and riot blend into each other.

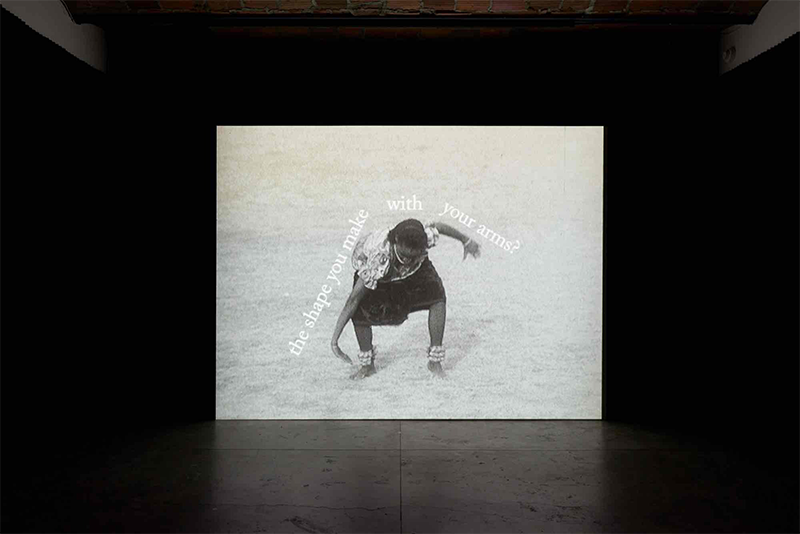

SPECIALISED TECHNIQUE (Onyeka Igwe, 2018).

SPECIALISED TECHNIQUE (Onyeka Igwe, 2018).

Recalling Déodat’s work with the séga, Igwe’s trio of shorts Her Name in My Mouth (2017), Sitting on a Man (2018), and Specialised Technique (2018) excavate the audiovisual colonial history between Nigeria and Britain.{10} Igwe recuperates the memory of the Aba Women’s War through a range of reenactment techniques. Braiding militancy and indigenous sociocultural practices, this women-led uprising in 1929 Igboland objected to the violations of women’s autonomy under colonization. The women’s rebellion was illegible to the British martial and historical conjugation of anti-blackness and patriarchy. Igwe’s counterforensics intervene in this gap. With the three-channel Sitting on a Man, the artist stitches together the imposed visual documentation of colonial-era dancing in Nigeria with a reimagining by two contemporary dancers, Emmanuella Idris and Amarnah Amuludun.

Igwe’s video work exemplifies the capacity of counterforensic, “investigative” aesthetics to provide a “way of assembling or weaving together different photographic and video images, in which each becomes a hinge or doorway to another source of information.”{11} Idris and Amuludun’s dance performs an alternative way to revitalize the memory of the past rebellion. They offer an embodied vocabulary of remembrance which, while unable to erase the harms of the archival footage, can supplement an expressive memory that extends beyond the borders of the imperial records. Unlike the static finality of the forensic, this tactic is not only formally but conceptually kinetic—not solving a crime but dissecting it into parts and rearranging the pieces. What emerges escapes the flatlined elegy for a singular “forgotten” event to instead offer a provocative demystification of the historical terms under which it was erased. Igwe’s resurfacing of the Aba Women’s War in excess of British colonial materials is open-ended and consciously partial, pointing to what must be an ongoing recovery and repurposing of black, African, and colonized women-led insurgent practices. The artist’s appearance at the end of a so-called archive is another example of the corporeal vocabulary she uses throughout her work. Igwe’s solo dance party in a warehouse is an embodied language of defiance, a rebellious gestural resignifying of what used to be a storage space for imperial records into a stage for her own performance, play, and pleasure.

Excerpt from SPECIALISED TECHNIQUE (Onyeka Igwe, 2018).

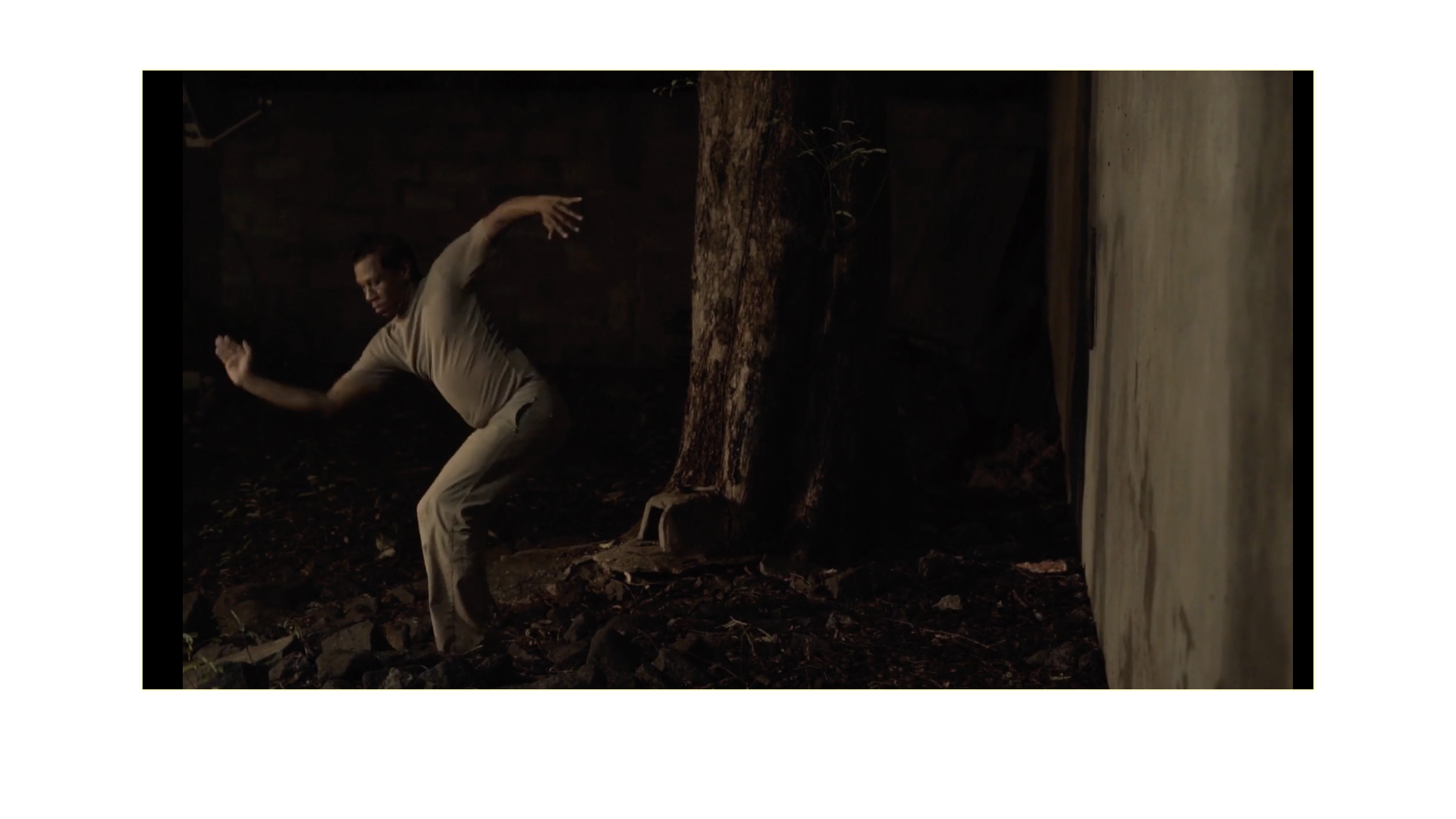

Déodat’s Sous le ciel des fétiches and Landslides also offer a dialectic of exposure and concealment, which the artist locates within the form of the séga. Landslides highlights the corporeal sensitivity of Déodat’s approach to history through the performance of Jean-Renat Anamah, a Mauritian dancer and choreographer. The video is Déodat’s persuasive claim to establishing an alternative modality of memory through an elliptical audiovisual ritual. Anamah’s lithe choreography is enacted through ecological contact, as he first shows up as only a hand on a tree trunk, reappearing on a rock seconds later with part of his body still outside of the frame. His slow, thoughtful movements draw the camera over another rocky mound and through the lush Mauritian landscape. From there, the video cuts to the mountainous verticality of Le Morne Brabant, glimpsed through a low angle as it peers out over verdant treetops.

Le Morne is imbued with historical and symbolic significance for maroonage, as it was used by the enslaved as a site of resistance and refuge, including escape through suicide by jumping from the mountain’s cliffs.{12} The topography of Déodat’s cinepoem is haunted, weaving black memory into ecological history. This interlacing is transmitted through Anamah’s interactions with the spectral landscape: His introductory contact with a tree shifts to his barefooted movement across the leafy bed of a forest, walking through rippling grass, and lying down on the wet sand of a shoreline and the packed dirt of a forest. As explained by Déodat, Anamah’s movements “conjugat[e] the vegetal, mineral and aquatic.”{13} The ancestral cartography of the séga embodied by Anamah is itself veiled, opaquely wired into his fluid movements of ecological communion and the billowy electronic score composed by Lorenzo Pagliei. In Landslides, Déodat sequences the theatricality of a haunted performance to open up a polytemporal threshold, where the delays and traces of a long arc of black refusals to domination and eradication coexist with the island’s ecology.

Déodat’s Sous le ciel des fétiches plays out two contrasting episodes of visibility and performance. With the gentle instability of a handheld camera, the video opens to silent black-and-white footage of a musical and dance performance at the Hilton Mauritius Resort & Spa. Alluding to the colonial continuum of tourism, the opening shot communicates from an observational distance a sense of voyeuristic intrusion. A modest stage of instruments and a nearby quartet of dancers, made up of three women in large skirts and one man, are presented as a spectacle for consumption. Next, sunlit footage of a woman casually dancing with a group of drummers counteracts the previous geometry of exploitative looking with its participatory communion. The tight shot—incorporating the at once total and negated vision of a solar flare—restores a sensorial wholeness, bringing together bodies, music, and tactility, in contrast to the removed observation in the prior scene.

Déodat’s counterforensic method reframes the first episode through the second. The juxtaposition denies any unknowing acceptance of the extractive logics which underlie the colonial capture of the touristic hotel spectacle, contrasting its formal alienation and isolation with the affective warmth and relationality of the corporeal and aural social communion that follows. Déodat uses the term oral images to describe her works, pointing to the polyphonic, polyvocal quality of the images that constitute her counterforensic choreographies.{14} Oral and aural plurality is shared among Déodat and the other artists as a vital dimension of the black memory they retrieve in defiance of colonial records and evidence.

****

Orality and Intertextuality

A WILLING SUSPENSION OF DISBELIEF + PHOTOGRAPHY AND FETISH (Christopher Harris, 2014).

The work of Christopher Harris and Languid Hands employs the voice as an intertextual instrument, transmitting another vector of embodiment in the testimony of black memory. Harris conjoins this with his efforts to unsettle how the camera, developed as a colonialist technology, functions as a recordkeeping device. His A Willing Suspension of Disbelief + Photography and Fetish (2014) confronts the anti-black, colonialist ideologies that shaped the materiality of the camera in both photography and cinema, while trying to find a way back to the subjectivity of effaced black personhood. The three-channel and split-screen video installation directly challenges the legacy of the Swiss American scientist Louis Agassiz. In the nineteenth century, Agassiz commissioned a series of daguerreotypes from photographer J. T. Zealy depicting enslaved Africans as a verification of biological racial difference. In addition to his work in the United States, Agassiz undertook the same visual assaults in Brazil—indicating the global scaffoldings of visuality.{15} Agassiz’s work exemplified photography’s function as a colonial technology, used to authorize slavery and colonization through its role in the construction of anti-black racial hierarchies. Delia Taylor was an enslaved black woman whose image was stolen and held visually captive by Agassiz, and who continues to be separated from her descendent kin through Harvard University’s claims of ownership, which themselves rely on a kind of forensic evidence.{16}

In Harris’s experimental video, an actor stands in as a hologramlike and thrice-multiplied avatar for Taylor. She reads aloud from an intertextual script that draws from Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida, Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, and Brian Wallis’s “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes.” The polyvocal ventriloquism and reanimation of Taylor render her a haunted citational presence. Shown with her breasts exposed, in profile and facing the camera, the reenacted Taylor is herself not safeguarded from visual vulnerability. Taylor’s afterimage cannot compensate for what happened to the person herself, but it does offer a corporeal renarration beyond the initial terms of capture. Supplementing the capacity to speak, the embodied performance writes over the enforced silence of Agassiz’s photograph. Harris’s aesthetic counterforensics find common ground with the other artists through the intertextual and polyvocal black testimony spoken by the actor. Without pretense that this strategy offers emancipatory repair, Taylor appears in multiplied kinetic choreography to deliver an oppositional discourse against the violently racialized, regulatory functions of the camera.

Collective voice and intertextuality are also essential tools in Igwe’s cinema. Sardonically incorporating the lax tone of museum voiceovers, which so passively celebrate violent conquest, a so-called archive adds in a polyphony of vocal fragments to formally defy the auditory cohesion of the colonial, institutional narrative. In Sitting on a Man, Idris and Amuludun’s choreography is juxtaposed with the voiceover of an anthropological text. The resulting clash between colonial visual and textual records and the dancers’ embodied reactivation of the 1929 women’s insurgency both exposes the clinically exploitative qualities of the British archival materials and performs how they can be retooled.

Oral storytelling, as another form of polyvocality, also extends to the counterforensics of the Jean-Baptiste siblings’ Écoutez le battement de nos images. Orality endures as an intergenerational inheritance that creates an acute counterlegibility—for example, when the film challenges the innocence of clips of the white French invaders at leisure by explaining in voiceover that such scenes came at the cost of the Guyanese population’s displacement. The Jean-Baptiste duo’s careful extraction of this history undercuts the dominance of visuality by leaning on the aural as a decolonial weapon of memory set against the evidence of colonial archives. Even the film’s title, a synesthetic invitation or demand to listen to the “beat of their images,” evokes an almost cardiovascular sense of the Jean-Baptistes’ moving image works.

In a similar way, vocality is made central to the familial effort of recovery in Nou voix. Jean-Baptiste père and fils attempt to unearth a speculative, spectral trace of Guyanese extras and participants in and around the making of Jean Galmot by conjuring a record of absent, ghostly voices. Two poems, “Listening to the Land” (1951) by Martin Carter, and “Air” (1969) by Derek Walcott, both written during the decade of continental African independence, supply an anticipatory vocal intervention. Suturing the words of the great Guyanese poet and the towering St. Lucian writer offers a Caribbean lyric of resistance to colonial cinema. Recalling Déodat’s approach, Jean-Baptiste’s orchestration of remembrance through voice and body is intermingled with ecology, which emerges in Nou voix’s citation of Carter’s poem:

I bent down

kneeling on my knee

and pressed my ear to listen to the land.

[. . .]

and all I heard was tongueless whispering

as if some buried slave wanted to speak again.

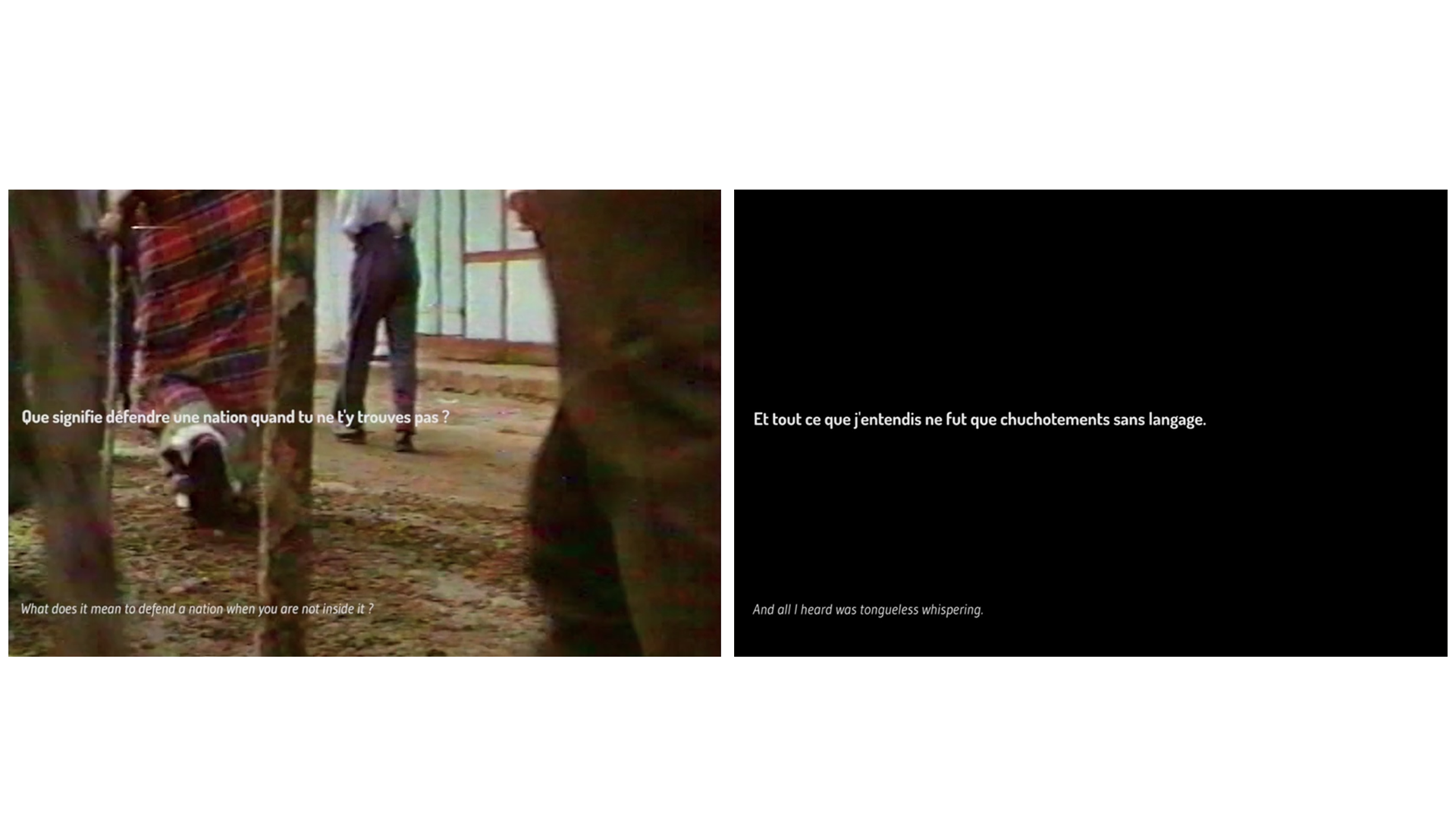

The unnamed Guyanese ground, like Le Morne Brabant in Mauritius, is a place where the memory of the earth meets black and African remembrance in colonized lands. After this poetic fragment comes a series of questions, delivered in Kreyòl by Gilbert Jean-Baptiste. The interrogatory litany includes questions about the stakes of remembering:

What does it mean to construct the memory of absence?

What does it mean to return to the homeland?

What does it mean to create an image of the present?

These questions play out on black-and-white title cards and as textual superimpositions on footage from Jean Galmot showing a group of people walking down a road, moving like marionettes in molasses. The father’s recitation of the questions in Kreyòl, like the incorporation of Guyanese music and poetry in Moune Ô, insists on a linguistic autonomy, unintelligible to the colonial ear. This approach stays attuned to the audible, even in suppressed histories of the colonized, on terms that do not defer to the demands of the colonial visual and linguistic system. With this understanding, what is enacted in Nou voix, Écoutez le battement de nos images, and Moune Ô is an archaeology sensitized to the “tongueless whispering” of the “buried slave” in Carter’s poem, understood more broadly as the black memory of the Americas. In both sound and form, the three films present the collective authorship of the Jean-Baptiste family as a “poly-perspectival assemblage” that draws on a collective remembrance of French Guiana.{17} As counterforensic efforts, the films do not presume to undo the persisting effects of colonization, nor do they get mired in an evidentiary objective to “prove” what happened, but rather leverage an oral, choreographic kineticism against the colonial record’s hold.

Towards a Black Testimony stages the polyvocality of an irrepressible ensemble, in ecstatic excess of containment. Interwoven with a cartography of appropriated images of riot, revelry, and their overlaps, Jordan’s voice speaks the words of Fannie Lou Hamer, Frantz Fanon, Dionne Brand, Fred Hampton, Audre Lorde, Pat Parker, Essex Hemphill, June Jordan, and more. Recalling the fragmented and multiplied voices in Jean-Baptiste’s and Harris’s works, in this vocal tapestry of black intertextuality, a presumably singular voice channels a multitude. This multitude’s rhetoric refuses the governing laws and norms of evidence and testimony:

Justice, then, for those sentient beings who experience the “total climate” of anti-black violence is not possible through the ritual speech act of testimony before a forum as we know it, because black testimony is illegible.

Illegibility is part of Languid Hands’ project, serving as an opacity that refuses the transparency sought by forensics.{18} Citing from poems, prayers, speeches, scholarship, and their own words, the duo creates an intertextual cacophony of black thought and expressivity that is protectively and defiantly illegible to the coercive forums of legal courts and punitive policing.

Music is also essential to the polyvocal defiance of Towards a Black Testimony. The subtitle of the work, Prayer/Protest/Peace, is taken from a 1960 jazz album by Max Roach, We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite, which features the sonic force of Abbey Lincoln. Scoring the quilt of video footage and accompanying the polyvocal intertext, Lincoln discards verbal language. She shrieks, wails, and screams an insistent demand for freedom that cannot be read within language or law. While the script read by Jordan remains audible throughout, the video’s sonic track upholds the opacity of Roach’s album. Languid Hands unleash a nonsingular sonic track of verbal and nonverbal testimonies of black memory as aesthetic counterforensics.

****

Looking and Law

Towards a Black Testimony fundamentally refutes the juridical schemas and legalistic machinery of evidence that corral black life. This assemblage of angular words and slippery images performs an unveiling, diagnosing the limitations of emancipatory discourses trapped in the limiting framework of human rights that assumes the authority of imperial and colonial systems. The intertextual rhetoric of Languid Hands acknowledges how assimilation and integration into anti-black state structures are not equivalent to liberation, calling into question the grounds of state and law in the UK and US. A vehicle for memory, black testimony presents a counterforensic interruption to the illusions of democracy, exposing the reality that claims of unity and equality are stabilized by coconstitutive mechanisms of exclusion. Towards a Black Testimony also offers an alternative:

Or put in another way, if we are made to say, I’m not going to waste my breath in a court of law. I’m going to testify to the black masses.

Languid Hands propose changing the terms of testimony from what is compelled by the law to what is shared among those criminalized by its structures. They identify how the forensic enforcements of legalistic coercion collude with surveillance and visuality. In Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness, Simone Browne locates the origins of contemporary surveillance in the slave ship—in the patrolling, policing, regulating, disciplining, and containing of black people. Browne offers “dark sousveillance” as an “imaginative place from which to mobilize a critique of racializing surveillance” that manifests in “anti-surveillance, countersurveillance, and other freedom practices.”{19} Dark sousveillance can be taken as another term for the aesthetic counterforensics of Languid Hands and the other artists discussed here. Towards a Black Testimony is a cipher of resistance whose stitched together testimonies do not yield to the comforting delusions of objectivity or false promises of transparency. Their method of black recoding is a counterforensic challenge to state visuality and colonial imagery that instead leverages the dark sousveillance of an intertextual black multitude and sonic opacity.

TOWARDS A BLACK TESTIMONY: PRAYER/PROTEST/PEACE (Languid Hands, 2019).

TOWARDS A BLACK TESTIMONY: PRAYER/PROTEST/PEACE (Languid Hands, 2019).

Harris’s practice also addresses how the legal architecture of forensics is both directly and obliquely opposed by counterforensics. His short film Reckless Eyeballing (2004) does so by contending with the act of looking itself, applying aesthetic counterforensics to blaxploitation and Hollywood cinema through a historical engagement of the law and racialized looking relations.{20} The title of Harris’s film creates a direct link to the juridical terrain of forensics and the measures of control and surveillance imposed on black people in the US. In her article “‘Reckless Eyeballing’: The Matt Ingram Case and the Denial of African American Sexual Freedom,” Mary Frances Berry describes the circumstances of

the 1951 episode in which Matt Ingram, a black tenant farmer in Yanceyville, North Carolina, was charged with assault with intent to rape a white girl, although he was 75 feet away from her at the time. He was eventually convicted of assault, however, based on her fear of his supposed “reckless eyeballing.” A systematic search for the details of Ingram’s experiences reveals how his release was obtained and the horrible conditions he and his family endured as a result of the false accusation during two and a half years of court proceedings.{21}

Harris situates Reckless Eyeballing within this legal, social, and theoretical history. With its Jim Crow–imbricated title, the film is a hand-processed composition that draws together Pam Grier in her Foxy Brown era, fragments from D. W. Griffith, and a wanted poster of Angela Davis. It centers on an exchange of looks, shaped through and against the place of black men in a scopophilic economy of gazes. As Berry historically contextualizes, for black people in a white-supremacist structure, the pleasure in looking or even the very act of looking replicated the same asymmetries of power as those in economic and social structures. The Ingram case indicates how this could unfold in a situation of gendered and racialized looking relations as another avenue for criminalization. The counterforensics of Harris reveal and trouble these geometries of power and distributions of violence across differently positioned gazes. Among the film’s formal tactics is a monochromatic inversion of many of the borrowed clips and images of looks, rendering black as white and vice versa. While the historical violence tracked across cinema cannot be erased, this chromatic recoding subtly and symbolically unsettles the stability of the racialized hierarchy of black and white it maps onto.

****

Memory and Repair

A solo dance party in an empty warehouse of stolen and forgotten objects. Phantom bodies projected onto a screen of wispy smoke. A celebratory colonial spectacle transformed into a tempo of refusal. Reenacted speech through a technology of capture. An intertextual scream of black masses in movement.

Incantatory, fugitive, liminal, and spectral, these aesthetic renderings of black memory are a call-and-response across intertwined geographies and temporalities of violence and survival. They exist as an oppositional record to the evidentiary forensics of slave-ship logs, plantation records, and their contemporary analogues in systems of capture and dispossession that continually reassert the authority enshrined by enslavement and colonization. Conjured in tongueless whispers and recited choreographies, black memory is the link between the living and the dead that no forensics can glean, intervening in how the past is encoded and inherited. It is channeled through the imaginative apparitions and audiovisual reengineering that create the aesthetic counterforensics of Igwe, Déodat, the Jean-Baptistes, Harris, and Languid Hands. The practices of these artists make no empty promise of full redress, but they bear another kind of testimony. Offering a memorializing rubric for the Afro-diasporic past, these films stage a supple, mobile, polyvocal dialogue and collective choreography. By way of demystification, imagination, and speculative supplementation, these artists offer a way toward an ethics of irresolution: Because the crime is still being carried out, the case cannot be closed. Escaping the hold of forensic evidence that only ever delivers a calculus of the suffering and exploitation already wrought, the aesthetic counterforensics of black memory attest to ongoing life—which is perhaps only another way of saying that the dead are with us, and we remember what we owe them.

Title video: Sous le ciel des fétiches (Under the Sky of Fetishes) (Caroline Déodat, 2023)

{1} Applied here to colonization but originally in reference to slavery, the term afterlives is used in the following sense: “If slavery persists as an issue in the political life of black America, it is not because of an antiquarian obsession with bygone days or the burden of a too-long memory, but because black lives are still imperiled and devalued by a racial calculus and a political arithmetic that were entrenched centuries ago. This is the afterlife of slavery—skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment.” Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), 6.

{2} While Raiford refers specifically to photography and the context of the United States, this term is helpful in an expanded global and formal lens: “African Americans have engaged in a practice of what I will call critical black memory, a mode of historical interpretation and political critique that has functioned as an important resource for framing and mobilizing African American social and political identities and movements.” Leigh Raiford, “Photography and the Practices of Critical Black Memory,” History and Theory 48, no. 4 (2009): 113.

{3} Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Duke University Press, 2011), 6, xv.

{4} Mirzoeff, Right to Look, 1.

{5} Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth (Verso, 2021), 12–13.

{6} Here also, there is a strong resonance with the “investigative aesthetics” of Fuller and Weizman, where they note the need “to use the occasion of its employment to offer deep introspection into—or critical self-reflection on—the way such technologies are conceived and operate.” Fuller and Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics, 5.

{7} Caroline Déodat, “Spectres de l’anthropologue: Les images numériques d’un ritual en différé,” Tsantsa [now Swiss Journal of Sociocultural Anthropology] 26 (2021): 173.

{8} Caroline Déodat, “Les métamorphoses du pouvoir dans le séga mauricien: de la ‘danse des Nègres’ au patrimoine ‘créole national,’” Recherches en danse, no. 4 (2015): 1. Author’s translation.

{9} Déodat, “Métamorphoses du pouvoir,” 1.

{10} Igwe’s three works screened together in the exhibition A Repertoire of Protest (No Dance, No Palaver) at MoMA PS1 in 2023, curated by Kari Rittenbach.

{11} Fuller and Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics, 13.

{12} “Le Morne Brabant,” Fondation pour la mémoire de l’esclavage, accessed November 9, 2024.

{13} Déodat, “Spectres de l’anthropologue,” 174. Author’s translation.

{14} “Caroline Déodat,” KADIST, accessed April 15, 2025.

{15} See Brian Wallis, “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes,” American Art 9, no. 2 (1995): 39–61.

{16} See Madison A. Shirazi, “Five Generations of Renty,” Harvard Crimson, March 18, 2021; Adetokunbo Fashanu, “Case Review: Lanier v. Harvard (2021),” Center for Art Law, July 27, 2021.

{17} Fuller and Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics, 6.

{18} On opacity see Édouard Glissant, Poétique de la relation (Gallimard, 1990).

{19} Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Duke University Press, 2015), 21.

{20} See bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation (South End, 1992).

{21} Mary Frances Berry, “‘Reckless Eyeballing’: The Matt Ingram Case and the Denial of African American Sexual Freedom,” Journal of African American History 93, no. 2 (2008): 223.