They Are Shooting at Our Shadows

The Al-Haq Forensic Architecture Investigation Unit and Rachel Nelson (Visualizing Abolition) in conversation with Laliv Melamed and Pooja Rangan

This conversation documents an exhibition that opened before it could be installed and which was, in the words of its curator, “never finished.” It is an effort by two documentary scholars, focused on humanitarian and settler-colonial media, to examine a collaboration between an abolitionist art initiative in Santa Cruz, California, and the forensic investigative unit of a Palestinian human rights organization in the occupied West Bank. Collectively, we surface and reflect on some of the latent assumptions and practices involved in gathering and presenting forensic evidence. Our shared account of forensics and its limitations is informed by the current moment, in which Palestinian human rights organizations have been criminalized, civil society infrastructures have been fractured and destroyed, and the ongoing brutality of Israeli occupation has been transformed into an active genocide.

Al-Haq is the oldest human rights organization in Palestine, established in 1979 and based in Ramallah in the West Bank. A collaboration with London-based research agency Forensic Architecture (FA), Al-Haq’s Forensic Architecture Investigation (FAI) Unit was founded in 2020 to support the organization’s legal investigations of human rights violations. The year after FAI’s establishment, Al-Haq was unlawfully labeled a terrorist organization by the State of Israel, along with five other Palestinian civil society groups. In August 2022 Al-Haq’s offices were raided and temporarily closed, and their computers confiscated. Since the designation, Al-Haq has been the target of digital and physical attacks, with its staff under immediate risk of raids, arrests, and reprisals. The affiliation with FA has offered some limited mobility on the ground, as well as a new set of evidentiary tools (spatial analysis, photogrammetry, 3D modeling) through which to ballast Al-Haq’s legal and public advocacy efforts.

For Gina Dent and Rachel Nelson, who founded Visualizing Abolition (VA) in 2020, Al-Haq’s criminalization reaffirmed the centrality of Palestine in their mission to dismantle carceral culture. Neither an art institute nor an academic institution (though it is affiliated with both the University of California, Santa Cruz, where Dent teaches, and the Institute of the Arts and Sciences, which Nelson directs), VA facilitates exchanges among artists inside and outside prison walls; abolitionists; institutions of higher education; art museums; performing arts venues; and the wider public. As such, it allowed the FAI Unit a flexibility not afforded by a traditional arts venue, as well as an opportunity to navigate the institutional frameworks of forensics and human rights from an abolitionist perspective that has in its sights not the reform of criminal justice or the international courts, but rather the end, altogether, of carceral enclosures.

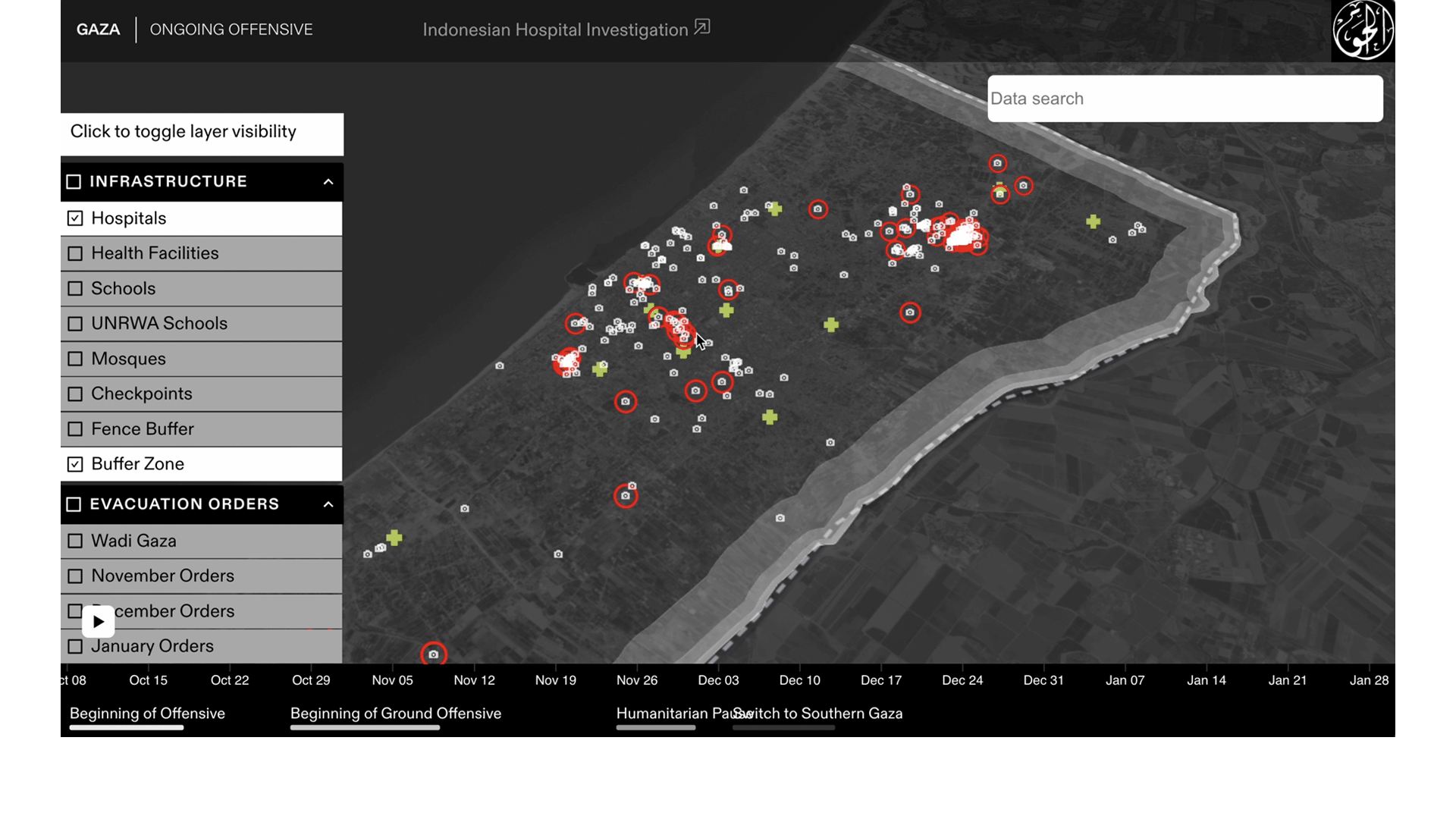

In July 2023, while the FAI Unit was planning the exhibition with VA, the Israeli military launched the biggest attack on the Jenin refugee camp since the battle of Jenin in 2002. The attack, which recalled the assault of 2002 and preceded techniques later used in Gaza in October 2023, became a central vector for the exhibition. The exhibition also investigates the killing of journalist Shireen Abu Akleh by Israeli forces and the IOF’s raid on Al-Haq offices. FAI was mere months into their investigation into the Jenin attacks when the genocidal siege on Gaza following the October 7 attack cut off Al-Haq’s access to field researchers for the first time in the organization’s history. With all hands on deck, the FAI Unit has since been absorbed in using open-source investigative tools to geolocate and document patterns of attacks on basic infrastructure in Gaza, and increasingly in the West Bank. As a result of these deadly interruptions, their exhibition at VA was missing parts for the entirety of its three-month duration. And although the exhibition was never completed, it is also not over: FAI’s Platform for Gaza, a continuously updated record of attacks, will remain on view at the Institute of the Arts and Sciences for as long as it is required.

The conversation that follows was drafted in October 2024 and developed out of five Zoom conversations that took place over the course of a month and a half during the summer of 2024 between Rachel Nelson, Laliv Melamed, P. Rangan, and two members of FAI. The FAI members are represented collectively to preserve their anonymity, and we have followed the same logic in representing the questions posed by Melamed and Rangan; however, there is one moment where we distinguish the two speakers from the FAI Unit in an effort to represent debates and conversations taking place within the organization. We also draw on a panel discussion that took place at the Institute of the Arts and Sciences in February 2024 in which a third FAI member and Gina Dent also participated. Two of our Zoom conversations were rescheduled because the FAI Unit had to rush to cover ongoing attacks, first on the Jenin camp, then on the Ramallah market.

We began our exchange with a version of a question posed by the black feminist scholar Tina Campt in her book Listening to Images: “What did it take for this image to reach me?” We felt that this question might allow a complex picture to emerge, of doing human rights work under occupation and violent surveillance, of Al-Haq’s negotiation of their methods and those of FA, and of the access obstacles, negotiation, and activism involved at every stage of reaching an international audience. Over the course of our conversations, this question took another form: What does it mean to produce subjugated knowledge under conditions of urgency—especially when the institutional avenues for producing and presenting that knowledge (forensic tools, human rights discourse, the art world) continue to operate at a pace that obdurately disregards that of Palestine?

In thinking through these questions, the FAI Unit, with Rachel Nelson, has articulated what they, following the Palestinian intellectual and revolutionary Jamal Huwail, call a “methodology of fire.” The components of this resolutely decolonial methodology include an emphasis on testimony as a first principle and an insistence on the political primacy of the fragmentary, the anecdotal, and the remembered over the accuracy and stability of legally admissible evidence. Their methodological provocations test some of the founding assumptions involved in normative uses of forensic analyses: that testimony must be corroborated by technology, that precision requires time, and that institutional proof is paramount. Our conversation comes to rest on the possibility that solidarity and collaboration can create the conditions for diagnostic critique while also doing the impossible, necessary, and always incomplete work of imagining collective liberation.

****

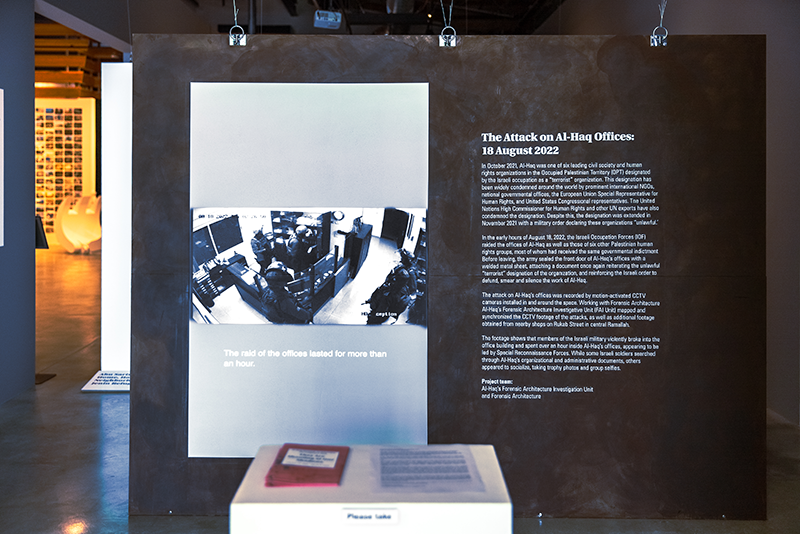

The Raid on Al-Haq Human Rights Organization

(August 18, 2022, Ramallah, Occupied West Bank)

At around 3:00 a.m., the Israeli Occupying Forces raided Al-Haq’s offices, alongside six other Palestinian civil society organizations.

CCTV cameras installed both outside and inside Al-Haq’s building documented the sequence of events.

At 3:24 a.m., the IOF violently broke through the front door of the office, while other soldiers patrolled the streets outside the building.

The raid of the offices lasted more than an hour.

The soldiers violently broke into the server room as well as into several offices, including the offices of Al-Haq’s general director and administrative department.

Throughout the operation, they took trophy photos and posed for group selfies.

Approximately forty minutes after their break-in, the IOF proceeded to cut off the power supply, effectively disabling the indoor CCTV cameras.

Ten minutes later, the IOF brought in a metal sheet and welding tools and sealed shut the main entrance to Al-Haq’s offices, leaving behind a military order demanding the closure of the organization.

Even the shadows, the memories of Palestinians, are being chased and attacked.

Laliv Melamed and P. Rangan

The very first thing one encounters at the entryway of the exhibition is a video showing the Israeli military’s raid on Al-Haq’s offices on August 18, 2022, projected onto a metal sheet. To have this as the starting point of the exhibition is really significant, since it is an immediate reminder of Israel’s criminalization of Al-Haq, the oldest human rights organization in Palestine and in the Middle East. Given this context, can you talk a little about how the framing of the exhibition—including its venue, structure, and timing—serves to document and respond to the intensification of violence and the evolving strategies of the Israeli military?

Al-Haq FAI Unit

One very important point is that Al-Haq never had an exhibition like this before. And it came at a time when a lot of funders, especially in Europe, were withdrawing or withholding funding pending investigations into Israel’s designation of Al-Haq as a terrorist organization. So we needed to push the boundaries of conventional advocacy and evidentiary work done with courts. The exhibition opened on January 12, 2024, three months after October 7, and during the huge protests in the US. So that was a signal that maybe appealing to the grassroots is a way forward, to try to escape the limitedness of the human rights framework into something that offers you a little more space to breathe.

Rachel Nelson

When Al-Haq’s offices were raided, a corrugated metal sheet was placed over their door. A notice was put onto it, declaring them a terrorist organization, though members of Al-Haq couldn’t read it because it was written in Hebrew. They had to use Google Translate to figure out what it said. The raid, the footage of the soldiers going around rifling through their things, was captured with Al-Haq’s own CCTV cameras. So the idea was that we were going to begin the exhibition by experiencing how Al-Haq—whose role has been to “watch the watchers” and to record the violations of the Israeli state—was forced into a position of being watched, violated, and punished. The framing of the exhibition was a way to reflect the change in Al-Haq’s orientation and also to reorient those coming into the exhibition by troubling the framework of universal human rights, particularly in Palestine, and the meaning of evidence in the context of an ongoing, genocidal occupation.

Al-Haq FAI Unit

The metal sheet and the video not only depict the raid, they testify to our memories of the office raids, and to the failure of the high-profile diplomats who constantly visited Al-Haq offices to prevent Israeli incursions. They testify to the failures of the human rights framework that promises safety and security for everyone. The installation also begins to draw out why we titled the exhibition They Are Shooting at Our Shadows, by which is meant that Palestinians are targeted not just physically but also in memory. It emphasizes that even the shadows, the memories of Palestinians, are being chased and attacked.

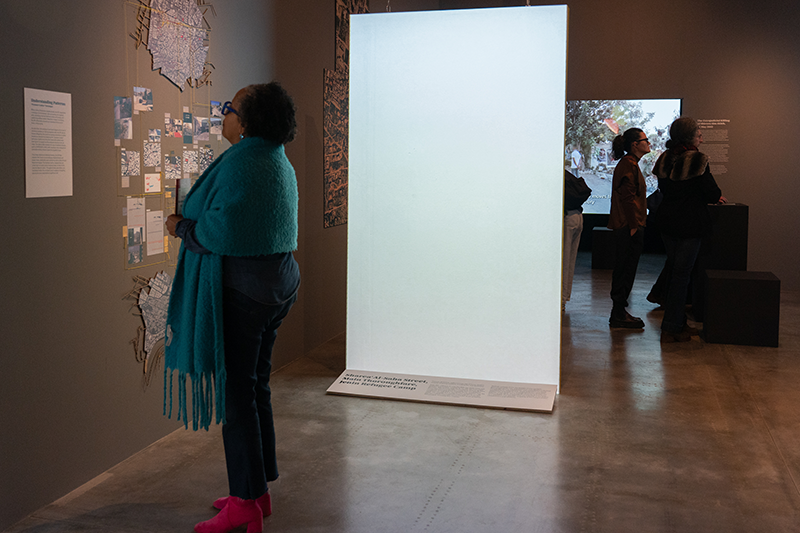

After the opening installation about the raid on Al-Haq’s offices, we worked to visualize the structures of violence that rule the daily lives of Palestinians, and to see what are often understood as individual acts of violence as nodes in a bigger map of occupation and oppression. In the exhibition, visitors encounter systematic acts of violence that were enacted specifically in the Jenin refugee camp, located in the West Bank, in July 2023—well before October 7. We see these incidents as foreshadowing similar tactics that have subsequently been used in Gaza. Three standing panels, collectively titled Understanding Patterns, are the next works that visitors experience. Through video, photographs, timelines, and charts, Understanding Patterns represents specific instances of violence: (1) house raids (essentially, the military takes over a Palestinian home and turns it into a base; they use the family’s furniture as barricades, and abduct the family by immobilizing the men and separating them from the women and children); (2) the “pressure cooker” technique (the military seizes a house and then bombs in its vicinity to close down the streets, so that people cannot come in and out of neighborhoods); and (3) aerial drone attacks (drones had never previously been deployed as an attack platform in the West Bank before July 3, 2023; now we’re seeing them everywhere). The three panels illustrate a continuous mesh of violence—created out of urban structures, architectural elements, checkpoints, and land-use policies—that the Israeli military has put together to make sure that Palestinians will keep their heads down.

Al-Haq Forensic Architecture Investigation Unit, THEY ARE SHOOTING AT OUR SHADOWS, installation at the Institute of the Arts and Sciences (IAS), UC Santa Cruz. Photo by Andrew O’Keefe, courtesy of the IAS and the artists.

Al-Haq Forensic Architecture Investigation Unit, THEY ARE SHOOTING AT OUR SHADOWS, installation at the Institute of the Arts and Sciences (IAS), UC Santa Cruz. Photo by Andrew O’Keefe, courtesy of the IAS and the artists.

LM and PR

Some might note that there are technological affinities between the tools you employ in this exhibition and those of the Israeli military. But in fact your exhibition—and indeed the very establishment of the FAI Unit—represents a tactical response to the evolving strategies of the Israeli military, and there is a distinct critique and methodology embedded in the way you use these tools. Can you help us understand this by sharing the history of how the FAI Unit came about?

Al-Haq FAI Unit

Al-Haq essentially has three main units. The Field Research Unit is the core unit that grew to become Al-Haq early on. The second unit used to be called the Visual Documentation Unit, and now it is called the Monitoring and Documentation Department; it is now the largest department in the organization, and the FAI Unit, which was established in 2020, forms part of that broader department. The third unit is the Data Bank Unit; they deal with organizing, storing, and retrieving data.

The FAI Unit is a collaboration between Al-Haq and Forensic Architecture, the London-based research agency that deploys forensic analysis to investigate cases of state violence and violations of human rights. The FAI Unit is led by folks on the ground in Palestine, and we combine the methodologies and open-source investigative tools [OSINT; open-source intelligence: an umbrella term for gathering and analyzing information from publicly available sources] employed by FA with Al-Haq’s established frameworks for documenting what we call “ground truths” (community-centered, firsthand testimonies of human rights violations). When the FAI Unit was first founded, I wasn’t even sure how we fit into the preexisting Al-Haq structure. After all, Al-Haq has been functioning since 1979 without us; there were already field agents who were gathering “ground truths” and others who were categorizing and compiling this work for use in various settings.

I joined Al-Haq shortly before Israel declared the organization a terrorist entity. I should mention that this is not a new experience for me; the school I went to was also labeled a terrorist organization! The Israeli state uses criminalization as a strategy to put Palestinian civil society at risk. The criminalization of Al-Haq in 2021 introduced a new realm of censorship, and the association with FA has helped to open some doors. For instance, when I’m stopped at a checkpoint, I show my FA card so they let me through. Or if I want to obtain satellite imagery, which they would never give to a Palestinian organization, I say I’m a researcher at Goldsmiths, or show my Goldsmiths email.

LM and PR

We briefly touched on the current moment, a moment in which your direct access to this texture of life and its distinct production of evidence is blocked. Could you tell us how the limited direct access to Gaza and the Jenin camp since October 2023, with the Israeli government cutting mobile networks and internet connections, has impacted Al-Haq’s operations, and what role the FAI Unit plays in overcoming these challenges?

Al-Haq FAI Unit

When October 7 happened, everything in Al-Haq was forced to a halt, because we no longer had field researchers on the ground in Gaza for the first time in the history of the organization, since 1979. And that was the moment at which we (the FAI Unit) turned to our peers and said, “You can rely on us to provide evidence.” This is the context in which OSINT became valuable for Al-Haq, because these tools allowed us to continue our investigative work from a distance. Beyond the three panels that we mentioned earlier, the exhibition also includes Platform for Gaza, an ongoing project. We set this up by scraping information from social media and other publicly available sources; we then created an interactive map that contains geolocated incidents of violence and tags to indicate the patterns of attacks, such as attacks on education, healthcare, etc.

But to build on your observation earlier, there is also a difference in how we are using OSINT. Unlike typical OSINT investigations that try to rationalize and forensically render the military’s actions, this exhibit uses models as narrative devices to convey the intimate, personal impacts of violence beyond written or recorded testimony. There is a fixation in the international open-source investigation community and forensic agencies on how to decipher and understand the modus operandi of the Israeli army. And they don’t see that there are Palestinians who are suffering because of this.

I’ll give you an example. The final installation in They Are Shooting at Our Shadows is the investigation of the extrajudicial killing of the journalist Shireen Abu Akleh in 2022. We created what we call a situated testimony—it was more of a reenactment, really—in collaboration with FA for the first time. It was a very interesting experience to do that, because we were speaking with a witness who went through the trauma of accompanying Shireen at the time she was shot. And we were just obsessing about the dimensions, about how far this witness was from the tree where Shireen was shot. The witness said to one of my colleagues back then, “I can’t do this; I want to go home.” This was a moment where the experience of violence was impossible to reconcile with the forensic methodological emphasis on getting the details right. It was heavy to try to intrude on trauma like this. And I remember the questions that we asked her, because we identified two rounds of shooting, the first round and the second round—it was as though we were speaking a language that she didn’t even understand. She said, “What drones? I just felt that the entire Northern area was shooting at me. I don’t know what drones.” So even though we were trying to invoke aspects of her memory, and she was generous enough to allow us to, this incident made us profoundly uncomfortable about our method. We need to think a lot harder about how we can interact with memory.

THE EXTRAJUDICIAL KILLING OF SHIREEN ABU AKLEH, 11 MAY 2022 (Al-Haq, 2022).

****

We begin and end with testimony.

LM and PR

Even in between these conversations we’ve been having, the Jenin refugee camp and other places in the West Bank are constantly under attack. The other day the Israeli army set fire to the Ramallah farmers’ market. The attacks on Jenin do not necessarily follow an “operational” logic, or a clear target. This brings us back to the point you make by naming the exhibition They Are Shooting at Our Shadows. It seems that the point is to attack the very basis of Palestinian memory. What is the camp as a site of memory? What is the camp as a paradigm of testimony? This strikes us as crucial, since you center your investigation on the camp.

Al-Haq FAI Unit

Yes, the Ramallah market was burned to the ground. Everyone has childhood memories of going there. We used to go there with our grandmothers. Now it looks like a strange space. It is not the market we know. Maybe now a developer will take this space and build a mall. One of the targets of the Jenin attack in late May was a statue of a horse built by a German artist together with the inhabitants of the camp, made from pieces of burnt cars in the aftermath of the battle of Jenin in 2002. The camp doesn’t have too many urban landmarks. The horse marked an entire area: the roundabout and the stores around. Now that the military has destroyed it, people still call this part of the city the “horse area.” That has something to do with memory. In recent attacks by the Israeli military it seems they are targeting not only people and spaces but also memorials, or anything that represents Palestinian essence or pride, anything that carries with it national aspirations.

It’s very hard to stay in the camp. There are constant raids and a lot of people are being killed in their homes. Still, we meet children who see the camp as their home. The camp becomes a way for people to preserve the memories of the Palestine they know. People from Haifa, from Jaffa are staying next to each other, and they have street names from Jaffa, from Haifa, from Jerusalem. For children born in the camps, their entire way of sociality and relationality and social structure is based in the camp—they would want to continue living in the camp even in a liberated Palestine.

In the past twenty years there has been a fundamental change in the psychology of Palestinians. Palestinians are being socially engineered to transition from being resistance fighters to becoming employees who are taking loans from banks. It’s perhaps a cliché, but actually the only model of resistance that’s still standing is the camp, and perhaps this is also why it has been consistently targeted. As I understand this model of resistance, people who stay in the camp are making a statement: “I am willing to announce my presence as a Palestinian by dying.” We might wish that something else could be said, and that there were other models of resistance, but this is what we are left with.

LM and PR

To say that testifying through one’s suffering or even by dying is the only way to assert one’s presence as a Palestinian is a powerful and damning statement. You are pointing both to the limits of a juridical framework that relies on testimonies of suffering, and to the thanatopolitical standards of evidence that have been applied to Palestinian life in international law and journalism. But even as you are critical of testimonies of suffering, your practice draws a distinction between the testimony of Palestinian people, which Al-Haq has called “ground truth,” and the forensic standards of proof required in order to make such testimony legally verifiable. How do you navigate these knots?

RN

This reminds me of something that [an FAI Unit member] once said to me: In the normative usages of forensic analysis, you corroborate the testimony through the technology; if there’s something you cannot corroborate, the fault is with the testimony. For the FAI Unit, the testimony of Palestinians is paramount. Palestine is the truth. If you fail to find the geolocations of it, it’s your failure and not the failure of the testimony. You never abandon the testimony. If you do, you end up corroborating the view of the Israeli state and their coconspirators.

One of the things we wanted to do in this exhibition was to actually be able to critique some of the tendencies of forensic methodologies, to be able to have conversations about what it means to lure the visitor into the position of the investigator—in a manner similar to a forensic television program like CSI: Crime Scene Investigation. This is incredibly hard, because when you’re confronting a genocide, you almost lose the ability to critique.

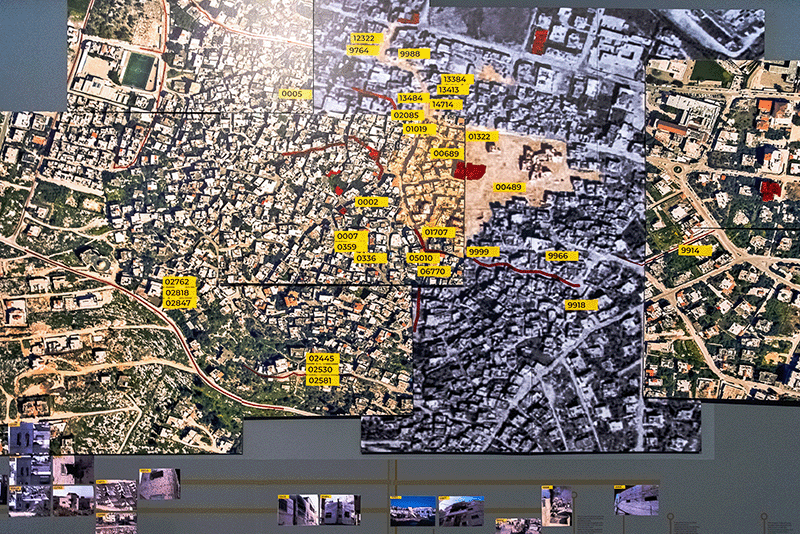

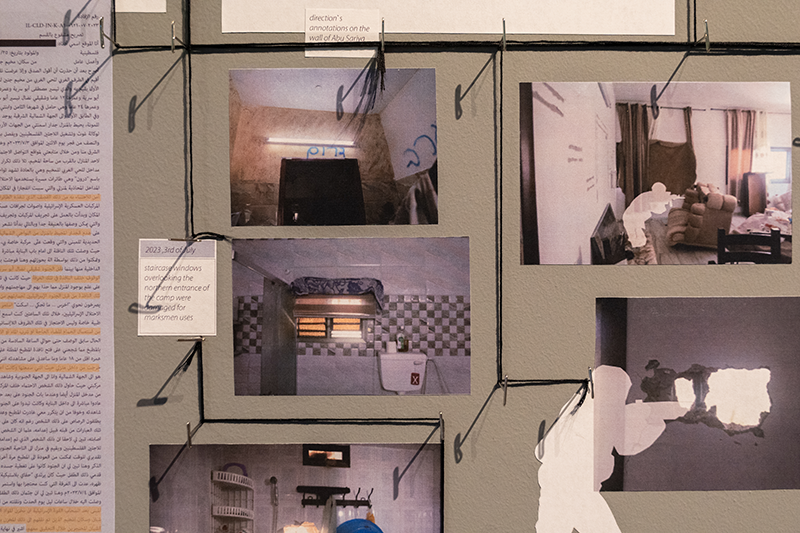

Al-Haq Forensic Architecture Investigation Unit, JENIN REFUGEE CAMP, 2002, 2024. Photo by Anne Martinete, courtesy of the IAS and the artists.

Al-Haq Forensic Architecture Investigation Unit, JENIN REFUGEE CAMP, 2002, 2024. Photo by Anne Martinete, courtesy of the IAS and the artists.

Al-Haq FAI Unit

What Rachel is saying about centering the experience of Palestinians is incredibly important. Most Palestinians have lost faith in international law and human rights. Working in the context of a human rights organization also puts distance between us and the communities we are working with, the communities we are from. So it’s not only difficult to reach the spaces of international law by talking in their language; it is also difficult to talk to the community, to talk to the people.

One of our field researchers works in Jenin, and most of his work involves going into the camp. I witnessed firsthand what happened when he met the father of a martyr—this is someone who was killed as a victim, who was just walking on the street and was shot. The father was in despair, crying, about to burst in front of the field researcher. Personally, I wouldn’t dare to say to the father, “I work in human rights.” At that moment, [an Al-Haq field researcher] said to the father, “You should be proud, your son is now a shining star. You should carry this pride with you.” The way the father smiled and became calm when he said that was really interesting. [The Al-Haq field researcher] had seamlessly transitioned to something outside the boundaries of the state, outside human rights, and made that family’s despair be seen. He produced a type of testimony that refused to be organized around state violence. He didn’t use the words human rights or say, “We want to prosecute the Israelis and destroy this culture of impunity.” It would not have worked, because Palestinians have grown very, very skeptical of the international community, and rightfully so—the culture of impunity has gone beyond Israel to a whole network of states complicit in the killing of Palestinians. When we collect genocidal statements made by Israeli politicians (for instance, for critical complaints in local and international courts) there is a thread that connects all of these statements together. And the thread is that they refuse to see Palestinians as human beings.

So we are trying to find a nearly impossible balance between, on the one hand, having a connection to things that are happening on the ground, and the people around us, even our families; and on the other hand, trying to talk to institutions and an international community that mainly looks at technicalities, not at feelings or human experience. When we work within a forensic mode of collecting evidence, of documenting and filing, it’s easy to forget the most important element, which is the human. We attend to architectural aspects, but we don’t concern ourselves with memories. We don’t care about experience in a way that puts it forward. We’re focusing on corroborating all information but do not notice how the events affect the people who live through them. For instance, we might talk with a paramedic who witnessed death with his own eyes, and we assume that he’s trained, he’s a professional, a specialist, but can we understand his experience? Someone from the London office asked people from the camp to upload video footage from their phones, but for people in the camp to share their phone cameras, first they need to trust you. Further, the video footage alone might work as evidence, but without that trust and taking into account the experiences that are behind the evidence, we fail to build a community or to care for a community experiencing this repeated violence.

JENIN REFUGEE CAMP 2002 DOCUMENTATION (Al-Haq, 2002).

LM and PR

On the one hand, the collaboration with FA has allowed Al-Haq to continue documenting Israeli war crimes using open-source tools and architectural tools like spatial analysis and photogrammetry under conditions of criminalization and mobility restriction. But as you’ve noted, the problem with forensics as a practice of verification is that it tends to discount testimony that cannot be corroborated. We also don’t want to romanticize testimony—we’ve heard you articulate a really powerful critique of human rights discourse, and how the reliance on testimonies of suffering shores up a juridical framework that has never provided justice for Palestinians. How do you navigate these complexities even as you remain critical of forensics as a method and epistemology?

Al-Haq FAI Unit

The difference between us and other forensic investigation agencies is that we begin and end with testimony. You can feel the tension between evidence and testimony, even in conventional forensic investigations. Testimony turns into a shell. Conventional investigations might begin and end with testimony, but this is just a mode of encasing the tactical investigation that goes into the integrated details. There is a neatness to it, a coldness, and it is given warmth through a few seconds of an interview with someone who experienced violence.

We have to remember that, historically, forensics has been used as a tool to capture Palestinians, take them to Israeli prisons. Even in our lifetime, this is how we heard the word forensics being used. Counterforensics has a different meaning for us than for someone who is a citizen of a state; they might say, “OK, the state is using its exclusive right to violence in ways that are not agreed upon by our social contract, so I am reclaiming these tools to assert the truth that is being obscured.” But there is no Palestinian state for us to reclaim these tools from, to address, or to hold accountable. To me this actually speaks directly to the notion of truth—again, the Eurocentric truth that has been captured by the Israeli state. Forensic evidence is the only language in which a lot of these elite institutions speak. The tools of architecture are colonial tools. The very idea of mapping Palestine came out of a British mandate that was premised on the possibility of replacing what was a complex and layered system of relating to land with a single layer, which is ownership. The FAI Unit’s work is about rearranging these colonial tools in such a way to allow for Palestinian voices, which are made absent and ignored when we do speak.

Precision, too, is a colonial value. Producing precise and accurate evidence is very hard. It involves a lot of time and effort. In order for our researchers to be able to do an image match, which is a format of translating an image from something shared on social media into evidence situated within a model, you need intensive training. It’s really hard, professionalized work, and a lot of people aren’t good at it. And when you are doing that, you run the risk that these people will be fixated on producing evidence, and then it’ll become their thing, like, “Wow, this image match is very, very impressive,” or “Your model looks super good, what a beautiful model,” in reference to the scenario of a horrific killing. So there are always these tensions and there is also the fact that we, as Palestinians, have been going through this for a very long time. In everything we are doing, we are stating the obvious, and that too requires patience. One of us is working on an investigation in Jenin where someone was run over by an armored vehicle. We talked to his father. The testimony with his mom is beyond heartbreak. It’s so, so horrific. And now we are talking about the model of the car that ran the victim over.

Weaving together evidence with testimony in a way that is respectful of the testimony is difficult. We think about testimony as a thread and evidence as the two sticks to tie the thread around in order to corroborate it or make it hold stronger. In a court, for example, it then becomes corroborated as one piece of evidence. We sometimes feel, Maybe our tools are not allowing us to corroborate their side of the story. And I think this is a very important distinction between our practice and the practices of a lot of these huge investigative units that are being funded in every single newspaper now in the US and everywhere. The difference is they don’t have anybody on the ground. This is not unlike going to the doctor, but the doctor doesn’t want to understand your pain, only to fix it. So to not have people who understand the history of the pain, of the ailment, is to produce and test hypotheses in an empty space without social context.

Al-Haq Forensic Architecture Investigation Unit, THEY ARE SHOOTING AT OUR SHADOWS, installation at the Institute of the Arts and Sciences (IAS). Photo by Anne Martinete, courtesy of the IAS and the artists.

Al-Haq Forensic Architecture Investigation Unit, THEY ARE SHOOTING AT OUR SHADOWS, installation at the Institute of the Arts and Sciences (IAS). Photo by Anne Martinete, courtesy of the IAS and the artists.

RN

Another thing to add about the way the FAI Unit is using testimony is that in the exhibition there were no representations of individuals or individual suffering. We discussed this and collectively rejected the human rights model in which we present an individual story as exemplary—in which structural violence becomes a story about one person that people are supposed to care about. The model of care we’re talking about is not a care for an individual but a larger constellation of care that attends to the details of the whole structure that enables violence—or maybe I should say, the structure that exists through violence—and responds with transformative care for and with the community on which this structural violence is enacted. There was a video that we had to pull from the exhibition because it was too explicit in showing suffering. The FAI Unit felt that now is not the time to show more Palestinian death; that the response this elicits is not the kind of care they want to work with.

****

The exhibition was never finished.

LM and PR

Rachel, we would like to hear you talk through the implications of supporting Palestinian liberation through an abolitionist framework. This seems especially significant in light of what has already been said about the way that human rights investigations are entangled in global juridical regimes, which rely heavily on the language of criminalization that has been employed to enclose and confine Palestinians in the first place. Can you tell us how you understand the relationship between your work at Visualizing Abolition and the work of the Al-Haq FAI Unit, and how your collaboration unfolded?

RN

When Gina Dent and I began the VA initiative at UC Santa Cruz, our objective was to change the narrative that links prisons to justice, and through art, education, and research, to contribute instead to the unfolding collective story and alternative imagining underway to create a future free of prisons. Palestine has always been central to our work and to the movement for abolition, because the Israeli state has come into being through a legal system based on carceral enclosure—it is in many ways the realization of the carceral apparatus in the state form.

We initially approached Eyal Weizman (founder of FA) because we were interested in working on an exhibition for VA that showed the work of FA in a few different locations as a means of tracing the global movement of carceral forms. But we were especially interested in the work FA was doing with Al-Haq, and wanted to commission an investigation from the FAI Unit that would enable them to continue their work.

We started talking with the FAI Unit about an exhibition about fourteen months before October 7, 2023, but as we all know, this current genocidal moment follows on the heels of decades of violence. Al-Haq’s FAI Unit had not yet done a public exhibition, and it took many meetings for us to understand what they and we wanted to do. One of the questions we asked was “Where do you fix the clock on this? What is the place from which you investigate?” When the raid happened in the Jenin refugee camp in July 2023, the FAI Unit went to Jenin, and as they began to research the raid, they realized this could be the basis of their investigation for the exhibition. This was the largest raid into Jenin since 2002, so they also had this historical context where they could compare the two moments. But July 2023 also reflected a real escalation of tactics by the Israeli state: using drones for the first time in targeted bombing airstrikes, targeting individual residences to turn them into military headquarters, and positioning snipers in organized ways. It’s not like those techniques had never been used before, but there was a clear tactical escalation that we felt needed to be recorded.

After October 7, everything changed. The main thing is that the FAI Unit had not finished their work on the July 2023 attack, but they were no longer able to travel to meet their collaborators in Jenin. Checkpoints were closed and conditions were extremely volatile. Also, the unit had to respond to and investigate what was happening in real time with the attacks on Gaza and the West Bank, so they got pulled off this project and had to begin processing endless amounts of material. The exhibition was originally supposed to open in December 2023, but they could not get everything together on that timeline.

We decided as a group to open on January 12, 2024, regardless of whether we had the materials—we were going to open the exhibition even if we had to open in an empty space. And luckily they were so far out in the design of the physical space that we were able to install the walls and the physical structures, despite the fact that we didn’t have any of the works that were to go into the exhibition.

LM and PR

It would not be an overstatement to say that the art world has been infatuated with the work of FA—their work has been featured in every major biennale for the last decade or so. But the Institute of the Arts and Sciences is not a traditional art institution. What did this distinction afford? We are thinking back here to our conversation about the need for institutional frames capable of changing to accommodate the situation in Palestine, rather than subordinating Palestine to their own logic.

RN

The question of whether or not VA was an art institution opened some different pathways. As you know, art institutions love the idea of FA, but when they actually start working with FA, many have then censored their work or tried to censor their work, or have tried to stop the collaborations. FA knew our history and the decades of abolitionist work at UC Santa Cruz and elsewhere that we’ve contributed to. And we were actually the first organization to ask them to do an exhibition in the US since their 2020 Homestead investigation (an investigation into human rights violations against migrant children held at a detention center in Homestead, Florida) led to the canceling of an exhibition.

The situation in Palestine is similar to the situation with the US carceral system, where all the data around racism in the US prison system has, as sociologist Ruha Benjamin and others would remind us, actually served to increase racism by normalizing the perception of criminality in relation to black and brown people. We see the issue for Palestine, like the US, is not the absence of evidence. We have an overabundance of evidence. For They Are Shooting at Our Shadows we needed people to encounter the evidence being shown in a way that shifted their relationship to it. One of art’s affordances is that it allows a cessation of arguing the evidence, trying the evidence, picking it apart. The difference between an art institution and a court of law is that art makes it possible to engage the evidence from a position of immersion rather than evaluation. The FAI Unit decided to build out the exhibition space in a very architectural sense, starting with a wall, then making it so the movement through the space was very controlled. They tightened the space so that the bodies were forced to move into it, to try to bring in a different perceptual environment. They were intent on creating an environment where people met that information through their bodies, in addition to the other ways in which we receive information.

Al-Haq Forensic Architecture Investigation Unit, UNDERSTANDING PATTERNS: HOMES MADE MILITARY BASES, 2024, detail. Photo by Anne Martinete, courtesy of the IAS and the artists.

Al-Haq Forensic Architecture Investigation Unit, UNDERSTANDING PATTERNS: HOMES MADE MILITARY BASES, 2024, detail. Photo by Anne Martinete, courtesy of the IAS and the artists.

LM and PR

In more ways than one, the process of putting the exhibition together reflects the impossibility of Al-Haq’s work, given the pressures under which they are working. The temporality of their work is impossible to reconcile with the temporality, structure, function, and design of an art institute. Can you talk to us about what it took for Al-Haq’s findings to reach an audience in Santa Cruz? And about how the Institute of the Arts and Sciences was itself transformed by serving as this conduit?

RN

It was impossible for us to act as if things would progress along a normative exhibition timeline, where you issue a press release, hang the artworks, project the videos, and host an opening with the artists in attendance. Ordinarily you would have the materials you need to produce an exhibition two to three months in advance. We had to install the exhibition whenever the FAI Unit could send us digital files of evidence—which happened to be after the exhibition was already open and visitors were in the space. They would sometimes send us a video that they hadn’t had time to edit because they were dealing with all this other material coming in. We typically issue an advance press release two months before an opening to announce the plans for events with the artists; this was not possible here, as it would have interfered with the ability of the FAI team to enter the US and return to the Occupied Territories. Only one member of the team has Israeli citizenship, which places them in a different political category than the other members, who have restrictions on their mobility within Palestine and Israel, and also face more scrutiny when traveling internationally. The team members came to the panel discussion on February 16 directly from the airport, where two of them were interrogated for an hour or so. It wasn’t until the interrogation concluded that they even knew they could set foot on US soil.

In all of these ways, we were operating in carceral time. In our work with people incarcerated in the US, time follows so many of the same patterns: the pauses when trying to share information or ideas, the communication issues, the interruptions caused by interrogations. It really drove home for us that carceral time is the time of Palestine. It’s worth noting that this different timeline that emerged around the exhibition, including publicizing it primarily after it opened and opening without any of the installations, is also why the exhibition hasn’t been written about, as art critics only want to write about shows that are about to open. Mounting it required radical flexibility on the part of everyone involved—and again, this is something we are familiar with from working with people who are incarcerated. What was the biggest challenge to all of us, however, was that the exhibition was never finished. It was open for three months but was missing parts for the entirety of its duration. So there was the metal sheet that was over the Al-Haq doors; these three standing panels that almost looked like the shapes of doors that hung into the space and had three projector lights turned on them, but no images; and then pieces of the walls, lit by spotlights, that also didn’t have any work on them. We didn’t get the installation on the investigation of Shireen’s killing (in the back room) up until really late—just a few weeks before the exhibition closed. Because the exhibition was never complete, we decided that it made sense to keep Platform for Gaza, which is constantly being updated by the unit to record the ongoing attacks, on view, even after the exhibition closed. We’re going to keep it on view for as long as we need to. So, just as the exhibition was never completed, it is not really over either.

With all the circumstances, we decided to make sure that one of us was always in the gallery during the run of the show, so that we talked to pretty much everybody that came through. We populated the exhibition with materials as we received them, but when we opened in January, we were welcoming people into an empty space and inviting them to think about the absences. We had a statement from Al-Haq, and we asked people to think about why we didn’t have any of the artworks in the space, and the many obstacles—bureaucratic, institutional, legal, and political—around elevating Palestinian voices and experiences. When a visitor came into the space, they would have somebody to tell them about what was going on, and to guide them through the work, or lack of it. Even as they were doing this, workers were physically in the process of installing work in the space. So it felt like the whole time we were showing people bits and pieces and talking about the impossibility of showing them the whole image.

LM and PR

Rachel just spoke about how difficult it is to align the timeline of an art institute with the multiple eruptions of extreme violence in Gaza and the West Bank. But the methodology of the Al-Haq FAI Unit also brings into view another misaligned timeline: that between forensics as a technology of visualization and factual verification that requires critical distance and reflection, and the temporal demands of working in the heat of the moment. In addition, the form of violence you are working to document dictates a temporality of “catching up” with a dynamic form of state violence that is extremely creative in coming up with new forms of assault and oppression. In one sense, through your exhibition we perceive Gaza as continuity, and in another sense, as a radical cut, a crisis. Can you talk to us about the methodological challenges of fabricating a timeline of occupational violence amid multiple ruptures?

Al-Haq FAI Unit

Jamal Huwail, a Palestinian intellectual from the Jenin camp, has offered us what he terms a “methodology of fire.” According to Huwail, Palestinians are constantly under fire. While we work we’re constantly being buzzed by text messages, checking updates on the news, while other colleagues are running in the corridors. We imagine investigations as something conducted coolheadedly, but here people are under a lot of hardship and some things just don’t make sense. Take, for instance, situated testimonies: You try to walk someone through a model via Zoom when they are in that zone of responding to other urgent matters, when they are under fire.

Al-Haq FAI Unit Member 1

Working within the splitting timelines of violence was something that perhaps wasn’t really thought about as much as it was worked on. I would say we work on this without having the space to think through the way the timelines come about. We live and work within the violence, so it all seems like one timeline, and we also try to simplify things just in order to catch up on a daily basis. In that sense, working on the exhibition, and also being in this space [of the gallery], allowed us to see the different ruptures, to get perspective, and to track the rationale that informs the violence. So, talking about Gaza, that was one of the biggest, most violent ruptures in what is a continuous form of oppression, something that forced us to discern different timelines; at the same time, it showed us how creating a timeline is very difficult when you work on things that are still happening in the present. Even in technical terms, we document while things happen, and often we cannot separate the progression of past, present, and future. We are unable to look at something after it finishes or foresee something before it happens. The exhibition allowed us to break from this.

Bal’out Family Apartment, Northeastern Entrance, Jenin Refugee Camp, video projection.

At around 2:00 a.m. on July 3, 2023, the IOF forcefully entered the Bal’out family’s apartment on the sixth floor of a building located at the northeastern entrance to the Jenin refugee camp. The father of the family and his two sons were bound, blindfolded, and secluded in one room, while the mother and daughter were escorted to a separate space in their apartment.

For the next two days, the family was held hostage by the army, forced to live in their home with the army as it repurposed their apartment as a military base for its operation in the camp.

Sharea’ Al-Saha Street, Main Thoroughfare, Jenin Refugee Camp, blank projection.

Soon after 1:00 a.m. on July 3, 2023, the Jenin camp was targeted with a major airstrike by the IOF—the first in two decades. This airstrike was conducted on Sharea’ Al-Saha Street, which connects the entire camp, with the targeted residence, belonging to the Habash family, located near the camp’s social club and also in close proximity to a UN clinic.

Through analysis of the footage of this incident, geolocation of the site, and testimony from Mujahed Mufeed Ahmad Abu Khoruj, a paramedic who survived the aerial bombardments while on duty, these airstrikes have been determined to be part of a strategy developed to treat the entirety of the camp space and its residents as a singular military target. Mufeed describes the intensity of the strikes as a relentless and sporadic targeting of the camp’s civilian infrastructure and residents.

Al-Haq FAI Unit Member 2

I find it very interesting that we tried to make sense of things in a place so distant from Palestine. It was striking to look at Jenin in the format that was exhibited in Santa Cruz, or to see it in that format after we documented it firsthand. What you’re illustrating here is the work of an archaeologist unraveling layers of violence and trying to remove a layer. And then by removing a layer, you kind of encounter another one.

When we started investigating Jenin in 2023 for the exhibition, we researched the archive of Al-Haq’s Visual Documentation Unit. We studied footage from the attack on Jenin in 2002. We saw that the same places that were the target of the attack of 2023 were attacked in 2002, and that a child who was interviewed in 2002 had become a resistance fighter by 2023. By trying to draw on these instances we could see the bigger structure of violence that rules and shapes the daily lives of Palestinians. So, going back to the exhibition, you see how all these events echo each other.

Al-Haq FAI Unit Member 1

I’d say the difference here is that an archaeologist could be unraveling layers of something that is static at that point, at the point of being worked on. You’re unraveling layers of something that is happening as you look at it. It’s like something is happening in the present time, and as you’re seeing it or as you’re experiencing it, you’re trying at the same time to analyze and figure out connections, figure out more deeply the strategies, patterns that are causing it to happen, or that come as a result of it happening. So this is why I said, in the end, it’s difficult for me to figure out or decide whether they’re eruptions on one timeline or actually on different timelines or different layers that are unraveling, because it’s not something that . . . it’s not a result. It’s still an ongoing process to be conducted.

LM and PR

Part of the difficulty of the work you are doing is that it requires faith in something larger than what we can see at present. In one of our previous conversations, [the FAI Unit] said something to the effect that it requires a certain level of irrationality to continue working in the human rights paradigm when it has failed Palestine over and over. In the face of this kind of structural failure, what aspects of your work—including this collaboration—allow you to keep an eye toward the long horizon?

RN

Gaza echoes Jenin in 2023, which in turn echoes Jenin in 2002—but of course it’s not just an echo you are talking about, but a training ground. So the exhibition was articulating this echo as a learning or rehearsal of tactics that could then be reapplied. This makes me think back to something that the FAI team said when they visited Santa Cruz. When they were here, we went and met with folks who were working on Abolish ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement). We met with folks who were formerly incarcerated. We really did some movement building. One of the things the unit said then was that they really have been struggling to envision what liberation means now for Palestine, but in stepping outside to have these conversations with people engaged in the struggle in the US, they could see nodes of what liberation was. They could see dots, and understood that if they could develop the dots, they could begin to connect them to make a fuller picture. And that’s really what we’ve been trying to do, working together to allow people to create visions, community visions collectively held, visions of what liberation and abolition is.

Al-Haq FAI Unit

In a panel discussion that we did with Gina Dent [on February 16, 2024], she asked us about the place of art in our work. Al-Haq is an organization of mostly lawyers. As architects [the two of us] speak in a different syntax and grammar. At the same time, it seems that a certain pressure is placed back on the idea of art by those who speak in these sober idioms, because the most important art, the most urgent art, does not require technical skill and can be done with a certain crudeness. The tactic of Israel is to actually destroy the very interiority through which a Palestinian would think of themselves as part of a collectivity, by splintering and kettling us into these little units, so that we’re unable to be in solidarity with another.

Personally, we don’t think that human rights work is the appropriate format or channel to free the land. One of the things we were asking while working with Rachel on the exhibition is what it means to have a structure that verifies experiences that actually have no sources of verification in reality, precisely because they have been obliterated by this occupying force. How to produce a different context for verification that is not grounded in legal verification, but rather in community-based forms of verification. This would be a kind of forensics with the capacity to model something which doesn’t yet exist, or which used to exist and doesn’t exist anymore. The capacity to verify something that exists outside other systems of verification.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank *** and ***** from the Al-Haq Forensic Architecture Investigation Unit for making time for conversation and reflection amid an impossible situation, and Gina Dent and Rachel Nelson for the necessary space they hold through their work at Visualizing Abolition. We especially thank Rachel for the grace and vision she brings to her connective work, and remain grateful to Jennifer Horne for facilitating our exchange. Benj Gerdes and Jason Fox are to thank for the oasis of time and support they created for workshopping this draft at the Institute for Futures Studies in Stockholm in the inestimable company, also, of Kari Anden-Papadapoulos, Shahram Khosravi, Christian Rossipal, Tess Takahashi, and LaCharles Ward.

Title video: The Extrajudicial Killing of Shireen Abu Akleh, 11 May 2022

(Al-Haq, 2022).