The Present Moment: A Conversation with Kirsten Johnson

Pamela Cohn

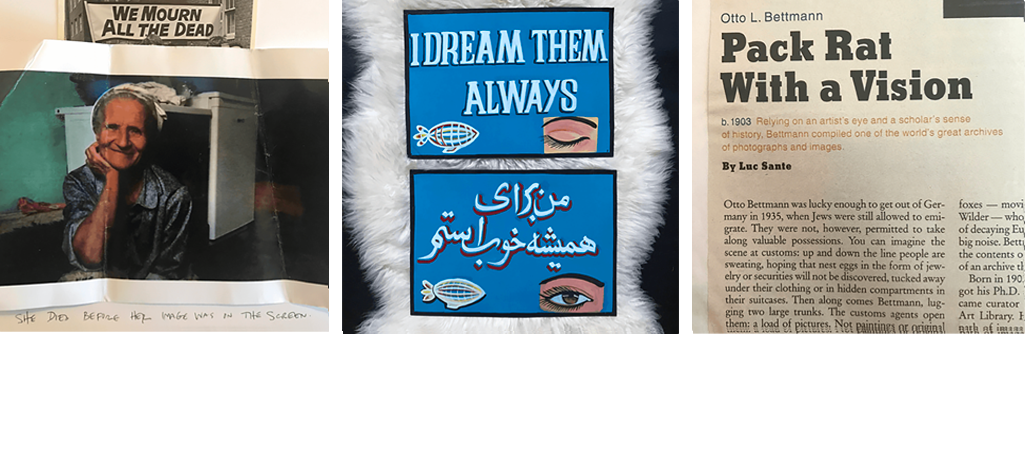

Most of us have become increasingly adept at navigating the abundance of what we experience daily as images – framing, capturing, and transforming fragments of our lives into networkable moments. Like loose snapshots thrown into a junk drawer, the images that inundate daily life are not really actively thought about or engaged with on any profound level. In fact, these images are seldom given a second thought and rarely resurface for further investigation, further interpretations of meaning.

When one’s job is to frame and capture moments that are meant to transcend the processes of abstraction that are embedded in any image creation, documentary production, and circulation, one might reflect quite deeply and profoundly upon how particular images can still retain their force and specificity. Kirsten Johnson has spent the last twenty-five years working as the director of photography on a long roster of significant documentaries including Derrida (2002), Lioness (2008), The Oath (2010), and Citizenfour (2014). The force and specificity and, most importantly, the impact of the images she frames and captures have become all-consuming issues for her.

Johnson’s most recent film as a director is Cameraperson (2016) made with the aid of editor Nels Bangerter. The film is visual memoir wherein she has carefully curated a handful of moments that, as she describes, indelibly marked her and changed her life forever. In her treatment of the images that she recorded for other directors’ films, she brings new life and context into some of the footage she’s shot over the course of a career, most of which has been filming various people in extremis. In this conversation, which stems from our decades-long relationship forged through a mutual devotion to constantly define what we do and why we do it in the realm of documentary storytelling, we hope to further investigate the challenges of searching for new ways to validate that work. Here, we talk further about the ways in which we are pushing ever harder for forward momentum in an increasingly noisy and over-stimulated world.

Interview

Pamela Cohn

After all these years of watching and writing about documentary filmmaking, I’m still grappling with the dichotomy between this supposed transparency of what’s being sought from a subject, a topic, and the various agendas being brought to bear on that subject or topic. And while you certainly grapple with this, too, in Cameraperson, there is also the strong thrust of craft in making a formally rigorous artistic manifesto. I think all of this, in some respects, has become harder and harder to unpack than it ever has been, so let’s start with the finished film and scroll back through time about the experience of making it.

Kirsten Johnson

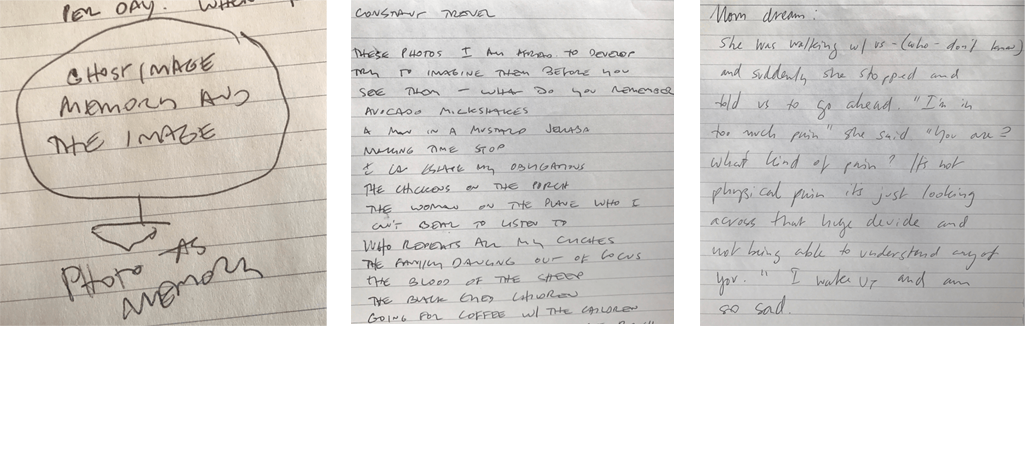

You know, I still don’t recognize it, this film. It doesn’t seem like it comes from me; and yet, it is obviously mine. We were formally interested in the idea that the audience could share the experience that I have as I film. But what I experience as a cameraperson is informed by who I am internally. And yet, the audience can only experience what’s in my mind based on the accumulation and contrasts of the footage we had to work with. We wanted to allude to all that cannot be said and all that cannot be known. Between our wondering about how to give the audience as much access to my experience as possible and the constraints of the footage, we made a film that felt transgressive and full of discovery even to me.

PC

What, specifically, was transgressive about it for you?

KJ

I was hired by directors making their own films and was working on behalf of their visions and ideas. In this film, I used that footage for another purpose, that of telling my own story, on my own behalf. I went through so many conversations with Marilyn Ness, the producer, about whom we needed to ask for permission in order to make this movie. We did succeed in getting the permission of all of the directors to use the footage and we did adhere to all the legal parameters already established around the ownership of the images, but part of what I’m deeply interested in questioning is, can images be “owned”? As the cameraperson for hire, I don’t believe I own the footage I shoot. Cameraperson is a film in which I claim some right to ownership of what I filmed. That is one part of it; but the other part of it is, what about the people filmed? One’s relationship to how one is comfortable with one’s image being used changes over time and cannot be foreseen. Even when a person signs a release form one day, circumstances may change the next day so that they may wish they had never signed away the right to use their image. Even your own capacity to assess whether giving someone else permission to use your image in whatever way they want is always compromised. I wanted our film to speak to this in some way. Once we had gotten legal rights and permissions from the directors I had worked with, there was no legal onus on us to get permission from the people depicted in the footage to use their image in a new context. But of course I see an ethical question in this. So we contacted and got permission from many of the people depicted in the footage in this new context, but at a certain point during our work it became clear that it would be impossible for us to get the permission of every single person I had filmed. In order to complete the film, I would have to bear the responsibility of using other people’s images for my own purposes without their knowledge. I realized that this implicit conundrum expresses one of the deep complexities of documentary filmmaking.

PC

Part of your innate talent as a cameraperson is your distinct ability to nonverbally ask permission from whoever is in the room. After all, it’s not like you’re moving around incognito.

KJ

No, quite the opposite. There is something fierce in the intensity of my engagement because I receive a lot of stimulation from all the information coming in, so I really am trying to connect and communicate with people as much as possible while I film. But there is so much going on that every day I film I have this sense that there’s a novel that could be written about just that one day. My imagination goes to the level of a novelistic exploration from the people I encounter. This happens within the first couple of hours of filming with someone. I’m plunged into a complex reality I’ve never imagined before. Body language, spoken language, the clothes they’re wearing – all of it gives me so much juicy, vital information. As I learn more about the context after the fact, more about the stakes, it’s then that I start to feel really struck by these more difficult and profound challenges of how incomplete the depiction of people always is. What I experience while shooting is an avid search for clues to what I am missing.

PC

Do you think you might have a tendency sometimes to over-see?

KJ

No doubt! Usually I think through what’s happening around me in relation to myself in a very concrete way. How am I able to move physically in the space? What are the limitations of the space and the light and how can I help us all move forward to get to what we want revealed? I am actively trying to avoid making assumptions and I’m scrambling to manage many constraints, including the technical ones, as well as to simply keep up with what’s happening as it’s unfolding. Having said all that, I will often realize that I thought that what was happening was not happening at all! I might be falling for a person when everyone around me is aggravated or having less positive feelings. But that’s interesting to me, as well – the times when everyone around me is resisting something and I’m being drawn in.

I can only know the moment I enter a situation, so I don’t know if the beginning of the scene that will eventually be cut has already happened or if it’s about to happen. One thing I always attempt to assess immediately is how much time I have in a particular situation. How much time do I have to search? How much time do I have to identify what’s really at stake? What are our subjects experiencing that is not immediately obvious? This is where I try to pay attention and stay open to all of the various themes the film is preoccupied by. Let’s say that some of the film’s themes are class divide, human disconnection, and symmetry. I might try to see if all of those themes can be found in a single shot. This is what determines whether it’s a wide or medium shot, where I position myself in relation to the people being filmed, or the proximity between the camera and those I’m filming. I will load shots or frames with as much information as can be found. Hopefully this is not something I’m imposing, but what I find there that will serve what we, as filmmakers, want to explore.

PC

I want to discuss a scene you chose to include in Cameraperson, the one with the girl whose face we don’t see in the abortion clinic. It raises my hackles a bit when a subject is being quite specifically directed in the midst of going through an exceedingly painful moment – and then on top of it, we can’t see her face. Her physical representation is truncated in the way you’re framing her. So I’m interested in your take of what’s happening there when the director is literally feeding her the line she wants her to say. What questions did you want to flag by including this segment?

CAMERAPERSON (Johnson, 2016).

KJ

The director, Dawn Porter, asks the young woman to start her sentence with, “If this clinic was not here…”, and then wanted her to explain what she would do. When I’m in a situation like that, I know the director is making a film with very explicit intentions to express something very clearly about a system. It is not her intention to just speak about a person’s emotions, but to contextualize how a person is caught within that system. As well as being a lawyer, Dawn has a deep understanding of the way racism relates to our nation’s stance on reproductive rights.

It was completely exhilarating to see the precision of Dawn’s mind at work in that context. She was very explicitly trying to gather what she would need to make a clear argument emerge from the very complicated and muddy political landscape in which abortion clinics are being attacked in such underhanded and deceptive ways. Dawn was searching for ways to reveal something that is purposefully hidden, particularly by state legislatures. She needed that young woman to speak explicitly about how she would be impacted if no abortion clinic existed.

I believe my role is to support a director’s needs and visions. But also, sometimes, my role is to support the person I’m filming in relation to the director’s needs. I’ve seen many directors torn by what they are asking of their subjects, especially if there is a serious constraint on how much time they get to spend with someone. These negotiations are fraught with conflict. I have great empathy for the many constraints directors face. They have to be aware of time and to push in certain ways that I don’t have to push. I have choices about whom I am advocating for in any given circumstance. In this case, what the young woman ended up saying — that if the clinic had not been there, she would have given the baby up for adoption — was what the film exactly did not need in this incredibly charged political context.

PC

You mentioned that you feel like you could write a novel out of a day’s shooting. Cinema is not literature and while it can have literary conceits, it can never offer what literature does. But we also talk about one single frame sometimes being able to hold a story that has the sensation of something one might find in a novel, an unnameable emotion that is evoked.

KJ

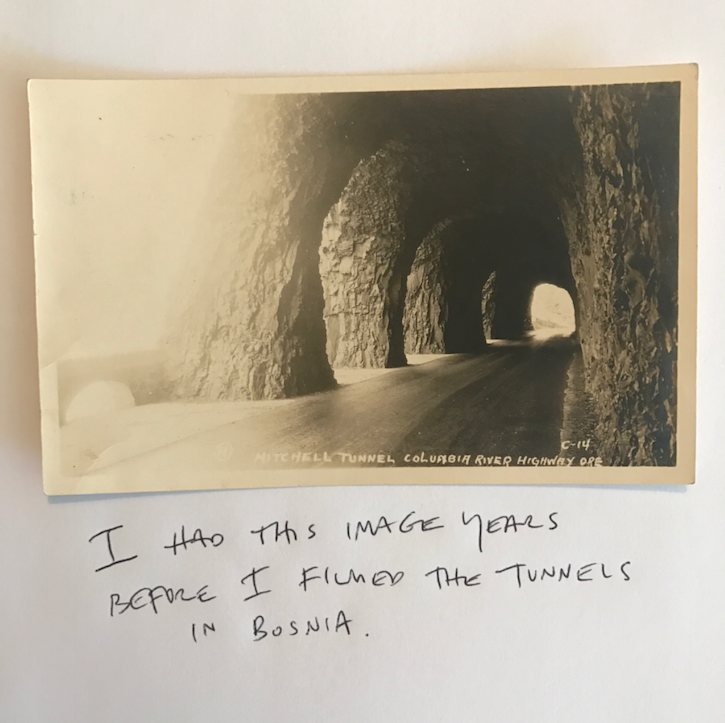

Yes, exactly. That is what had happened in the act of filming the scenes that I chose to put into my own film. Those experiences continued to live inside me long after they were recorded. The sensual, pleasurable moment of that sunset on the side of that mountain in Bosnia; or the self-punishment of the young woman in the abortion clinic; or the horror of the sound of the chain that had dragged a man to his death being dropped back into an evidence box. I don’t want to say that I necessarily knew this at the time, but by filming those moments in the way that I filmed them, I internalized them. When I was filming the chain in the courtroom scene with the lawyers, I was so frustrated. I felt I was filming it inadequately. I was thinking to myself, the carpet was ugly, my frame isn’t right; the plastic box doesn’t have a gravitas that matches the enormity of the crime. But then when I heard the chain going back into the box, I felt something that I have never forgotten. What I thought I remembered and couldn’t forget are the images I saw in the evidence book. But when I went back to the footage, I realized how deeply that sound of that chain going back into the box was buried in me. Because it had entered me so profoundly and was so disturbing, I realized that I had buried it away from my conscious mind. That’s how painful that was. So while the material I chose indicates ideas and questions or areas of thought within documentary, as I say in the beginning of the film, all of what you see in the film marked me. That’s what makes it my memoir. It transformed me as a person.

PC

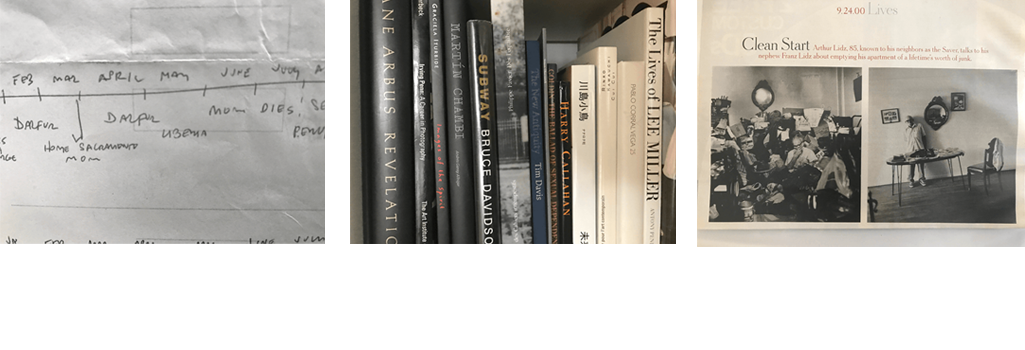

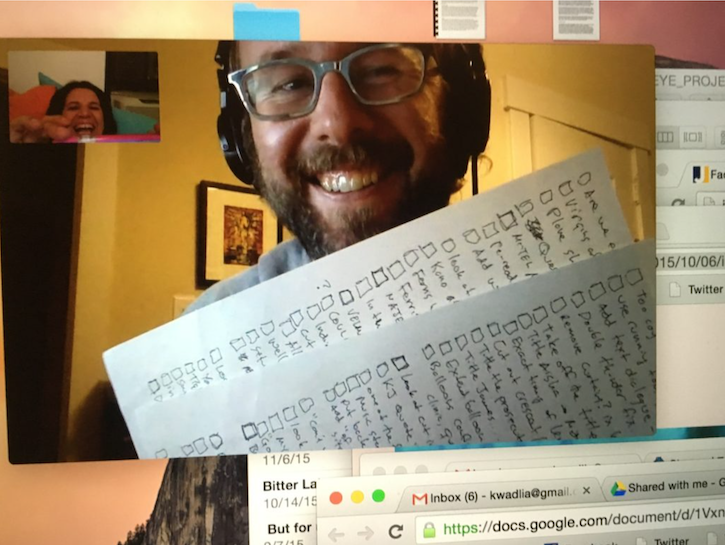

There were many attempts and failures of putting this series of intense moments into a narrative. When you finally met Nels, you decided that he would be a trusted and expert miner, ultimately enabling you to make a film that is open-ended, elliptical, and spacious enough for multiple interpretations.

KJ

Before Nels came on board the first thing I experimented with extensively was the use of my voice. The impossibility of what I needed to express in words became very apparent. I so badly wanted to include the breadth of what I had experienced. The amounts of time, the quantity of places, the aftermath of the number of genocides … I needed to express something specifically about the scale and multiplicity of what I had encountered. That was really important to me. Needless to say, the film became wallpapered with words in a way that made any entry into the film impossible. I became unbearable in my explanations of context. In the many attempts at voice-over I tried, I could never succeed in expressing all I had felt as well as all of the connections I saw. It was impossible to verbally express all of the context.

PC

What changed in terms of that context then when you wanted to use those scenes as elements in creating your memoir?

KJ

When I film, I always have this incredibly complex internal monologue going on about what I think might be happening and what the film wants to follow. What’s the storyline? We’re in a maternity ward in Nigeria. We’re following a story of a woman who’s pregnant with twins and one of them is breach and there is no doctor. We want to show how perilous it can be for a woman to have children in a place that is under-resourced. I am thinking about my own wish to have children and how different it would be for me if I were in an American hospital having children. I am having feeling for this woman who may lose one baby but still have a baby at the same moment I fear I will never have a baby. I feel shame for even thinking such a thought while she is fighting for her life and the life of her baby. I’m thinking about the blood on the floor and I’ve just learned that the patient who is bleeding has HIV and I’m wondering if I’ve cut my body somewhere because I often bump into things and scrape myself when I film and I’m not always aware of that. I’m thinking about the battery running out. I’m wishing I had the three-to-two plug that would make the oxygen machine work. Is there time to send the driver home to get it?

This is why I feel like a novel could be written almost every day that I film. I thought I could tell the audience all of that. All of that stuff I just told you? I could keep talking for another hour about what was going on in that maternity ward for every thirty minutes we were there. I really thought I could put all of that into a film! But I finally realized that it was a hopeless cause. What surprised me about giving up on a voice-over was to see how much of what I wanted to express verbally was actually in the images. Not all of it, of course. The three-to-two plug for the oxygen machine is an incredibly brutal detail that I really wanted to share with the world. I knew I had to give up what, to me, were critically important details like that one because it wasn’t in the footage. When Nels and I first started working together, I told him stories like this and I would get extremely emotional because when I tell that story of the maternity ward, I’m back there. I’m stepping in the blood. Nels could quickly parse it all and would say to me, “Well, we see that and we see that and we see that and we hear that … and what else did you want to say?” (laughter) He could deflate my grandiose notion of wanting to express the forty things that were going on in my mind when I was filming. He’d tell me, “We can see thirty-nine of those. Is that fortieth one so important?”

Johnson with editor Nels Bangerter.

Johnson with editor Nels Bangerter.

PC

The way scenes are juxtaposed with other scenes – the old woman in Bosnia, Sejio the driver, Velma the translator, the women in Darfur, even Derrida – all are, in some way, proxies for you, all become your narrators.

KJ

I would say that the role of proxy is mutual – they can be seen as my proxies, but I am also theirs. We have shared the experience of acknowledging what has happened, or what is happening. And we share that experience from completely different positions. In most of these cases, what we’re sharing, simply, is impotency, the utter impotency in the face of how horrible the world can be, how terrible life can be. None of us wants what is happening to be happening.

In the hospital in Nigeria, we all wanted that baby to live. We all knew that baby was a healthy baby an hour before and that he should have lived. The father, the mother, the midwife, the director, the sound person, me, the grandmother, all the nurses – we all shared that knowledge. But there was no outlet for the oxygen machine and there was no doctor who came who could have, and should have, done the C-section. We sat with the midwife while she waited knowing that, at a certain point, if she didn’t pull the baby out, both mother and child would die. We all sat watching the clock tick while she knew no doctor was coming. So who’s a proxy for whom in that situation? We are all impotent together and we have witnessed one another being impotent. We also witness one another each doing what we can do given the circumstances. For that reason, how the father, the mother and the midwife behave are heroic to me. For some reason, I actually thought that by filming all of this, maybe everything could be okay. So that’s an instance of downright delusional thinking because we came to this hospital knowing that it has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world. Our purpose was to show the world this so that, maybe, the world would respond to this crisis.

CAMERAPERSON, Kirsten Johnson (2016).

CAMERAPERSON, Kirsten Johnson (2016).

KJ

In principle, you’re there for the future. But when you get there, you’re in the present. The reality of the present is that the midwife puts numbers on her chart of how many women died that week and how many babies died that week. She was there for all of those deaths. And she’ll continue doing the same thing week after week. This is the reality she knows and that she is staying in – whether she’s being filmed by me or not. I am discovering that reality, coming into that with no defenses. Hers are built because she needs to enable herself to continue to do her work. Maybe that’s why I feel that it’s part of my work to render visible what I am seeing for others because my defenses aren’t built up since I don’t have to stay there. In Q&As after screenings of the film, people have asked why the midwife didn’t walk faster, as if that would have changed the outcome. That’s what I had to learn to own during the process of making my own film: that I could be misunderstood, that the young woman seeking the abortion could be misunderstood, Dawn Porter could be misunderstood, as could the midwife. Intentions and feelings of empathy do not supply actions or outcomes, nor do they mitigate unintended consequences. Those things are separate and interact with each other.

PC

This question: What can the camera do? is something you’ve been grappling with in the context of what you’ve been doing with a camera for decades.

KJ

Yes, but another question viewers ask that has everything to do with the person operating the camera is: Why are they allowing that to happen? In other words, where’s the intervention? Sometimes not knowing how to, or whether, one should intervene is absolutely unbearable! Years after the events, I am still contending with the choices I made there. We filmed that baby struggling to live for 30 hours. That’s obscene. But at a certain point, the father of that baby didn’t want us to stop filming. I interpreted his smiles, his touch and his presence as his need for us to continue. But I could have been totally wrong about that. That’s how I interpreted it and that’s why I continued. I also think I continued simply out of my own hope that it would turn out okay. It wasn’t finished. What we did learn after the fact was that the hospital put extra effort in trying to get that baby to live because we were filming.

From the director’s production notebook.

From the director’s production notebook.

Let’s imagine the scenario in which I only blame myself for continuing to film. It would appear that my presence caused doctors to be pulled off of other patients who needed them and that I gave hope to a father in a hopeless situation, that my presence forced that midwife to keep trying despite the certain outcome that was so obviously a lost cause to her. We could even say my presence prolonged the suffering of the child. There are ways one could interpret all of that to be true. My intentions, we could say, were decent intentions. I did not intend to harm anyone by filming. But the thing I don’t know about life is what did that mean to the midwife to be given more time and space to contend with the slow dying of that baby? If I wasn’t there, she would have walked away from that situation as soon as she had assessed it – as she does most days of her working life – meaning in the first minutes after pulling the baby out of the mother.

PC

She does walk away.

KJ

Yeah, and she came back because we were there. The camera forced open time. Its presence forced certain interactions between the key players, including myself. It forced all this unknowingly. In that forced open space – which I’ve experienced many, many times – some very painful and some very beautiful things have happened. I value and honor that, the not- knowingness of whether that’s right or wrong. If the images I create of that experience continue to live in the ways they seem to live, that situation echoes. This is not a scene one can forget easily after seeing it. I have no idea where that sits on a moral scale of good or bad. Being there with my camera is what made that play out as it did. That’s all I know.

PC

You could have made a whole movie based on all those moments you’ve experienced in that way.

KJ

Yes, an unwatchable one. (laughter)

PC

I feel in this bid to always make context king, sometimes a distinct lack of context is the more appropriate way to encounter all the bizarre things that happen. This lack of context enabled me to connect more readily to what might have been happening with you emotionally while filming.

KJ

Nels and I found our way to a place where we wanted certain things to function with the least amount of context possible and still find a way for it to be accessible. We went as far as we could with that. At one point, it was my voice as wall-to-wall narrator to explain everything. And then we thought we’d need a ton of cards to explain everything. Then we would need the names of all the movies for which the footage had been shot as signifiers. It was a process of paring away all of that.

PC

Derrida nailed it. As you’re filming him, he says about you: “She sees everything. She’s blind.” When you talk about your time in Nigeria and that shoot in the maternity ward, you said that in principle, you’re there for the future, but when you get there, you’re in the present. How then does this change the relationship of making this kind of work, work that exposes this kind of footage in specific contexts to viewers? What about this expectation that some kind of direct action should be taken when they see it? We become witnesses too in the act of watching it. This is a time of taking to the streets, a daisy chain of protests by massive amounts of people against what they perceive as being damaging not only to themselves as individuals, but to the whole of humanity. We are able to also now see video of someone being murdered in cold blood embedded right in our Facebook feed. That’s documentary, isn’t it? Are the same social documentary imperatives that have been in place for decades still relevant in this climate, with these new modes of communication that are immediate and quite brutal? You don’t have to be a journalist moving yourself to a war zone several continents away. People that live in that war zone are documenting themselves living in that war zone. And still nothing much seems to happen in terms of what we could term “social change.”

KJ

I think that the imperative has become to acknowledge that you can, and you must, ask all of these questions of yourself. Why are you there? Are you hurting people? How are you representing people? What do you think you’re making? These can all be really troubling questions. The time of hiding from any of these questions must be over. I do not deny that some of these questions are in deep contradiction to one another. One might say there’s no need for any person to leave their country of origin to make a film. That’s an important perspective to address given the history of who’s made images of whom and in service to what. I think the capacity to explore such questions in the context of identities and their relevancy is a critical piece of the puzzle. If we hide relationships of power and identity that are a part of a film, that is a disservice to us all. You cannot go to a place and pretend that it doesn’t matter that you’re a foreign person making the film. If you are putting your life at risk or putting the lives of the people you’re filming at risk, or the ones helping you make the film at risk, you have to own it.

Maybe you are making something that has a very particular agenda, one that is much different than the people there would make, and that’s incredibly valuable. You could be wrong about those reasons. You could be wrong about those choices, but you must own all of it. Every single one of us has to own all of who we are in this world of image-making.

Background Video: Cameraperson, Kirsten Johnson (2017)