The Glitter Within

Arjuna Neuman

The opening scene of Hiroshima mon amour (1959) has buried itself in me. It lives a few millimeters under my skin. It crawls across my epidermis, tingling, pattering, exciting, shivering, calling to attention the hair follicles that perforate the living and dead layers that surround me: my supposed body’s boundary, my sovereignty.

As the opening images cross-fade a little too slowly, the boundaries of skin (like the edges of the filmic cut) embalming the two bodies onscreen are all confused editorially and visually: we know not whose arm is whose, whose hand is whose, whose touch is whose. As dust, glitter, and soot fall on these bodies, those with even the mildest synesthetic proclivity will feel their own skin and flesh come alive.{1} Importantly, this is felt, not identified. The characters onscreen have not yet been shown through the traditional grammar of narrative cinema: through access to the face and bodies, close-up or mid-shots, these synecdoches for psychology or visual identity, projected and reflected back. Rather, the effect here is sensual, but it’s also, paradoxically, material (sooty), a haptic-optic onomatopoeia where matter and sense collide through something much closer to motor resonance, skin-worms, and synesthesia—a cinema not so much for the eyes, or the eyes alone. The falling soot-glitter materializes what a caress feels like on both the inside and outside of skin and bodies. This not knowing whose touch is whose scrambles any idea of a body being sovereign, definitive, or singular—instead creating the sense impression of a corpus infinitum. What are caresses if not the pattering fall of dustglittersoot, an all-over, all-under set of sensations that belong to neither bodies nor their sovereignty? With touch also always comes heat. Heat transfer happens as if it were tiny bits of warmed dust-soot, rubbing across, against, and through skin, down the quivering follicles, through the tunnels of pores, shaking the phonons held in crystalline lattices that store and share hotness, sound, murmur, touch—our infinite synesthesia connecting matter.{2}

Putting aside the geopolitical history of Hiroshima mon amour for just a moment, without diminishing its importance, but at the same time to give space to a different, perhaps quieter starting point. Instead, I want to begin (and end) with the chill-sending element that invited me to feel otherwise about political cinema: the dusty, falling, sooty, shimmery glitter.

****

The eyes ought to be held in suspicion. As an epistemic cornerstone of Enlightenment thought, elevated to the top of a biosensory hierarchy, the eyes have attained what we might call anatomical supremacy in Western culture. Philosophers from Plato to Aristotle to Descartes to Kepler to Kant describe sight as the most noble sense. We trust the eyes to decide on factual, observable, rational knowledge; they are the means by which we make distinctions and see the truth.{3}

The conflation of sight with knowledge/truth has been routinely singled out in critical responses to Modern Knowledge and the enduring epistemic violence of the post-Enlightenment.{4} The critiques are familiar across Black and decolonial studies, as well as media theory following the Situationist and Frankfurt School traditions, where, for example, the centering of sight/knowledge is a metonym and therefore a logical, albeit linguistic, justification for the centering of Europe, home of reason.{5} When this nobility of sense is made to determine a nobility of race, the conflation can be, and often is, used against itself, toward a kind of reverse engineering or unlearning—decenter or deconstruct opticality and European colonial power will supposedly fade from view. At least this is the textbook decolonial approach and aesthetic-critical strategy we see repeated in much art and visual theory today.

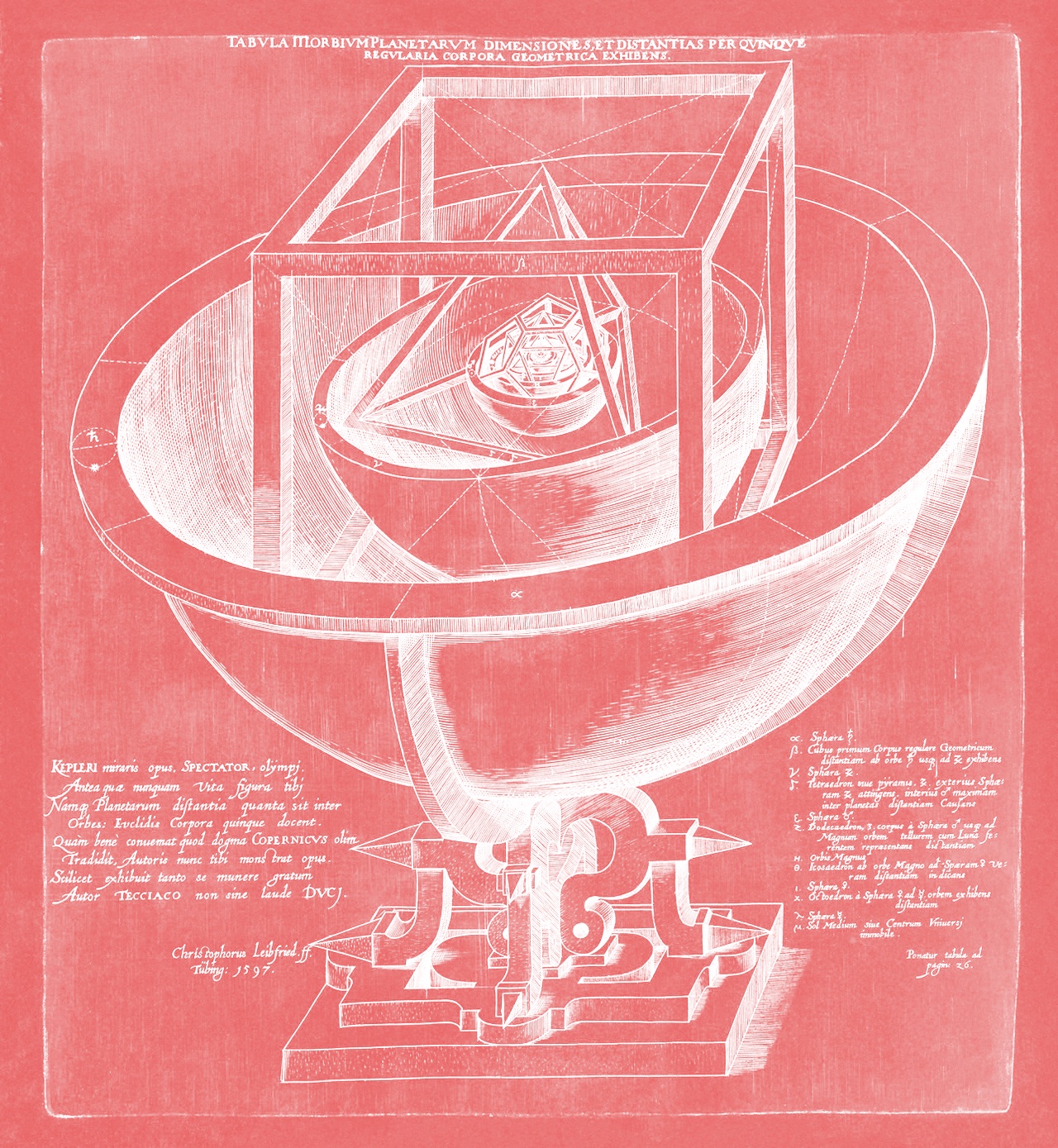

MYSTERIUM COSMOGRAPHICUM, with Kepler’s model illustrating the intercalation of the five regular solids between the imaginary spheres of the planets.

MYSTERIUM COSMOGRAPHICUM, with Kepler’s model illustrating the intercalation of the five regular solids between the imaginary spheres of the planets.

To take this conflation to its absurd limit, if sight is how a differentiation of races is classically and historically made, and color as a visual phenomenon is determined by wavelength, then racism appears as a problem of optics and physics. We would merely need to unlearn the visual spectrum and classical physics more generally for racism to disappear. This of course ignores the material—both economic-historical and embodied—basis of racial violence. Yet it does explain some of the excitement in decolonial circles around quantum physics, since this collection of relatively recent scientific theory turns so much of classical physics and the epistemic dominance of observation on its head (e.g., the Heisenberg principle)—science deconstructing itself.{6}

If racial difference is visually observable—remembering observation is/as scientific method—racism is thus a physical property and therefore scientific fact. This false logic, stemming from a metaphorical conflation, is baked into language and the history of Western ideas. It is exemplified when we use words like reflect to mean think about. And this is how much we take this epistemology for granted, how its violence hides in plain sight, and how significant a purchase it has on our imaginary and the way we experience and legislate the world. Yet, all too often, criticism rests at the metaphorical or conceptual level, meaning it can only ever identify the conflation and then substitute for knowledge/observation other, supposedly reparative metaphors, such as knowledge/entanglement or knowledge/relationality.{7} Of course, these practices have very real sociopolitical consequences, even if they are language games.

This critical lineage might expand beyond the closed loop of metaphors and substitutions by considering how the eyes are biological, and how various anatomical hierarchies sustain biocultural tendencies and dispositions to act in a certain way. When it comes to the role of sight in sustaining systems of racial oppression, most of the critical emphasis has been placed on either representation and inclusion or visuality and optics, with scant attention paid to the very material and fleshy means by which these questions of politics or physics are enacted. What if we begin instead with biology and anatomy before we arrive at sight? Then, the critique might edge over into ontology. Instead of reconsidering the way we process sight and therefore think or experience the world, we might begin to contest and reimagine our very physical predispositions to the world—these would be the mutable and plastic preconditions to action and being, embodiment and bodies.{8}

The turn to questions of the flesh has also been advanced by material developments in biomodification practices, neuroplasticity, epigenetics, and the trans revolution. And yet we have a long way to go, as the critical approach across the last two generations still sticks a little too closely to a path from mind to body, physics to biology, or from thought to feeling, where blurring (Moten), opacity (Glissant), representation (Campt), and deferring to other senses (Black Audio Film Collective) are still common strategies of resistance for displacing the supremacy of sight and its endless authorization of racial violence. My intention here is not to critique these approaches, nor even to point out their blind spots, but rather to build on these ideas and to collaborate with them in reverse: beginning with a material critique of the biological edifice that our eyes constitute, and ending with a reimagined epistemology—that is, with a proposal that turns away from both the European tradition and much of the recent critical work against it, and instead asks not only how to know and feel the world otherwise, but also how to enter it differently.

****

In preparation for an interview with Hortense Spillers, I watched various lectures of hers on the terrifying history of love as it comes to us through North American slave relations. Spillers describes how love, post-slavery, cannot but be “contaminated.”{9} Contamination or collateral violence, for Spillers, emerges from a set of relational practices that begin between the master and slave, and between rapist and victim. The ubiquity of rape is a well-documented part of the normalized reality of slave culture. Spillers describes how such violence would also seep into the relations between the master and his family, his wife and children. Rape, even if it was legally sanctioned, or at least looked over, could not be compartmentalized as just one part of one’s life. Put more directly, if a master rapes his slave, how then could he hold his wife and children with love, with the same hands? Love, after all, is one of the tools we have against violence, and here we learn of its integral relationship to predation.

As I watched Professor Spillers, my eyes burning a little, it occurred to me that just as we take the onto-epistemic foundation of love for granted—forgetting that beneath its shiny veneer lies a much darker, tainted history—we also take our eyes for granted. Not just their gaze and epistemological legacies of vision and visuality, but their very physicality, their ontology, their fleshy, anatomic significance, or what we might call their sense supremacy. It occurred to me that parts of our body, such as our eyes or our emotions, can be contaminated by ideas and overdetermined by hierarchies, which together produce all kinds of collateral damage. We can call this disorganization of the body’s ecology a monoculture—where privileging one sense rather than all five equally is a path to catastrophe. This is not to say that the body has an ordained, essential path. There are, however, tendencies that, when partnered with modes of determination, framing, abstraction, and hierarchy-making, lead the body as nature toward legacies of violence and exhaustion.

Our human eyes embody a certain disposition toward the world that can be described, biologically speaking, as predatory. We know that prey animals have eyes that are more laterally spaced; this gives them a wider peripheral vision, better to spot a stalker sneaking up behind them. Think of deer or rabbits, whose eyes can scan the horizon. Humans have the eyes of a predator: front and center in the head, with a keen and narrow field of view designed to isolate prey, sometimes at a long distance.{10} More recently, and more controversially, humans have been described as “superpredators,” since they kill about thirteen times more animals than the next level of the food chain—the debate revolves around killing for food, and whether or not to include killing for other reasons, such as wildlife control, sport, or cruelty.

Alongside the science, popular anatomy and its folk (white Western) imaginary has described the placement of human eyes as similar to fierce and dangerous animals such as wolves—think of words like hawkeyed and lynx-eyed. This has helped reinforce and sustain notions of human supremacy and its hubristic exceptionalism—humans as supposed apex beings with innately violent tendencies. Even today, many still believe humans to be not only the top of the food chain, but somehow paradoxically separate from nature, even godlike (technology and its crypto-mystic origins helps reinforce this identification). This legacy has helped rationalize and engender not only violence against so many animals thought to be below humans and therefore edible or expendable, but also violence against so many Black and brown bodies who have been rendered animal or nonhuman and therefore equally disposable. Prey by another name.

In addition to this self-designated “great success of the human species” is our “exceptional” use of tools and technology that supposedly separates us from nature. Of course, tools are augmentations of the body, selectively intensifying and accelerating tendencies or talents that already exist—think of telescopes for augmenting the eyes, or clothes as second skin. Epistemic tools have followed suit, again selecting certain features, dispositions, body parts, or senses that by way of abstraction lead us into specific overdetermined futures.{11} Take, for example, what we described above as a monoculture of the body, the consequences of making one sense nobler than the others. What is important to underline here is that both types of tools, physical and epistemic, rely on a material base, a foundation as something to build on and abstract from. This epistemological and abstracting process itself has a very material history.

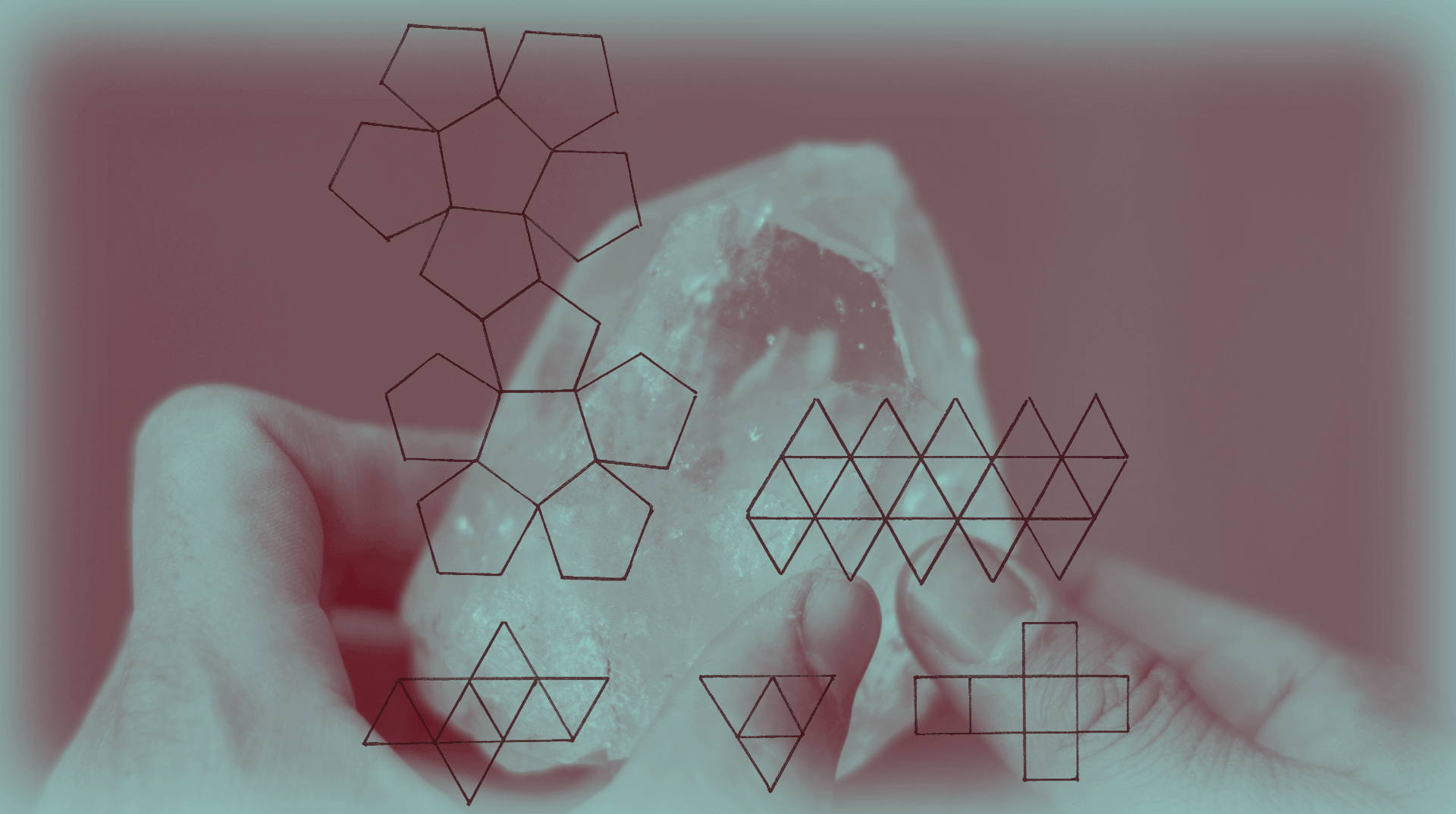

The crystal found collected and globally traded across early hominids was the means by which abstract thought through geometric rendering is believed to have developed.{12} This material bridge from object to geometry was made possible because of the crystal’s unique form—namely, that it is one of the only stable objects with naturally occurring straight lines and complex symmetries. Not only did this property propel the development of geometric abstraction, but the crystal also began to emerge as something precious, a symbol of wealth and an accelerant of the desire to accumulate. In short, it is the earliest documented example of what would become modern-day resource extraction. Abstraction and accumulation, therefore, are two sides of the same coin, or rather, the same crystal. Each motivates and justifies the other. At root, these pillars of modern-day life are inseparable.

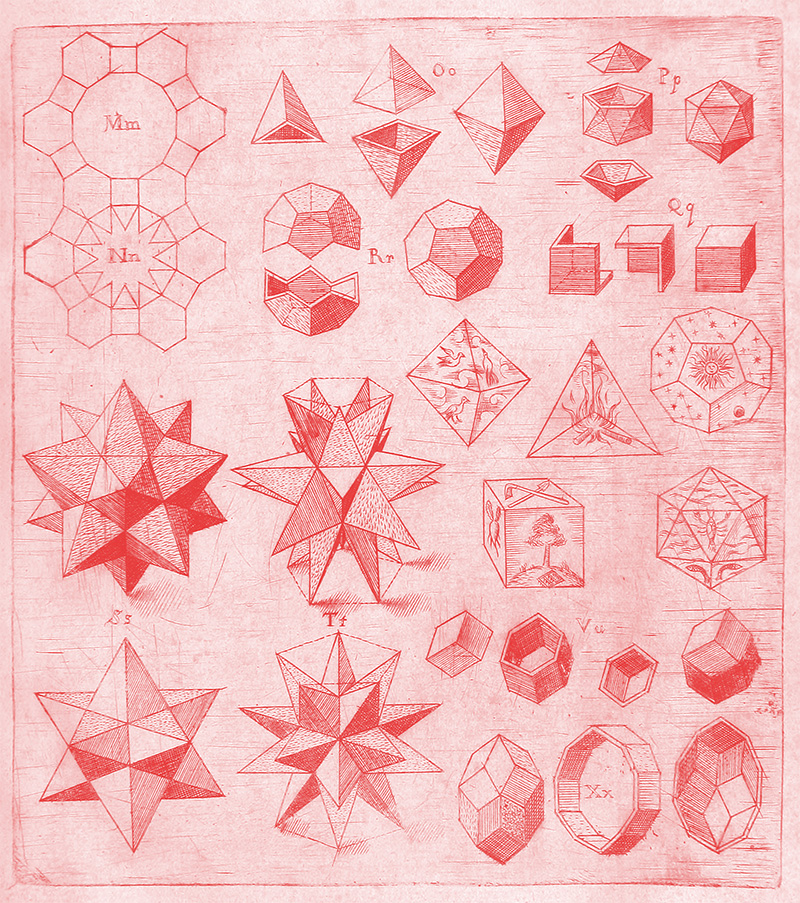

The geometric and abstract description of the world can be broadly traced from the crystals carried by early hominids through “prehistory’s sacred geometry” to Plato, who allocated a platonic solid to each classical element, to Kepler, who in the early 1600s described the world as constituted by geometric forms (platonic solids revival): the cube, pyramid, icosahedron, octahedron. It was also Johannes Kepler who embodied this cosmology, putting it into anatomical practice through ophthalmology, discovering that our eyes function like a camera obscura, that an image symmetrical with reality is projected directly onto the human retina. Such a direct and linear link from the world to the mind made the eye the key to objectivity. This process reinforced, modeled, and even naturalized the abstraction of dualism, as moving from the physical world to the abstraction of mind, light/reason quite literally being projected in and reflected from the mind like a camera. Kepler’s theory was a key moment in the Western history of ideas that fused the eye and its rational optics with Modern Knowledge.{13} Remembering that the 1600s was an accelerated moment of European colonization, in particular marking the exponential growth of slavery in the US: in other words, the rise of abstraction is twinned by a rise in global resource extraction, and all the violence that entails. Figuratively speaking, the sides of the same crystal, abstraction and accumulation, sight, knowledge and extraction, all shining deathly bright.

As the eyes were continually centered in the project of rationalism and the Enlightenment, a new function and ordering was instrumentalized. Collaterally, fixing sight as the noblest sense ennobled, enabled, and prioritized an ancestral predatory instinct that in turn continues to authorize and justify the human’s placement as apex species—that is, ordained as naturally violent. This designation forestalled, blocked, and even hijacked a potential different configuration of the human (as nature, genre, and biology), a transformative, even evolutionary step where our eyes, or even the wider ways we see, should or could have mutated otherwise.{14} This in turn could have demoted, softened, or even rendered obsolete violent instincts, or the parts of the human that potentially determine that orientation. Put differently, any type of hierarchy or monoculture, whether in terms of race, crop, or sense faculty, has both causal, direct consequences and many indirect consequences—just as in Spillers’s description of the contaminations of master-slave rape in the collateral master’s family, or the contamination of groundwater across a region through practices of monoculture. The placing of eyes and sight above and beyond all the other senses has had many causal effects, such as the role of observation in rational science, as well as many nondirect, collateral, or ecological consequences—that which perhaps more dangerously hides in plain sight.

A parallel and complementary explanation for this violence has focused on Blackness/identity, where the slave and to a degree all non-Europeans were constituted as nonbeings, as animals or even less-than-animals incapable of having souls or minds. In our contemporary moment, this has led to the emergence of approaches that prescribe rehumanization or equal representation as the solution to antiblackness. This approach operates in the domain of subjectivity and identity, proposing space to live out one’s full, if previously denied, potential. But subjectivity and subjectivization were always a significant part of the slave trade and racial capitalism—namely, this was the way in which slaves were valued. If, for example, a slave had a good temperament they could become house slaves, escaping the more punishing work of the cotton fields. Such slaves on the auction block would receive a higher sales price. The practice of selective breeding on plantations meant subjective and even physical qualities could be nurtured and reproduced, and therefore the value of the stock increased over time. This marks the limitations of identity and subjective modes of resistance as they blindly support racial capitalism and its prototyping of immaterial identity labor—the sheer value of certain identities in today’s cultural marketplace should be evidence enough of the inherent problems in, and shortsightedness of, this approach.

Geometric figures (platonic solids and other regular polyhedra). Source: Kepler, HARMONICES MUNDI LIBRI V (1619).

Geometric figures (platonic solids and other regular polyhedra). Source: Kepler, HARMONICES MUNDI LIBRI V (1619).

As grim as the prescriptive and predatory anatomical basis of our human disposition is, especially when combined with the current fad of representation-based neoliberal reparations, there is a rather clear route to an undoing. If we displace or mutate the ontological basis of knowledge and/as predation, the anatomical (culturally determined) supremacy of our eyes, then an entirely new body and way of being in the world becomes available to us. This move cannot only be a “redistribution of the sensible,” something like substituting the ears for the eyes, hearing for sight (in any case, this would be inaccessible to some—i.e., would reinforce hierarchies). No single sense exists uncontaminated by cultures of domination, yet shifting emphasis to hearing and even touch is certainly a start, especially since these senses are activated inside the womb—meaning they come to the fetus/mother when the fetus/mother is yet to be separated and sovereign. We might call these monstrous senses, senses laced with the memory of being multiple before we are singular.{15} In this way, while colonial determinations have been encoded into all our senses, monstrous, prenatal, multiple existence and its potential synesthesia might help us begin to undo some of the collateral damage that noble predatory eyesight has unleashed on the world. Going further, though, the subversive and mutational gesture would be to acknowledge our anatomical plasticity—for example, by reconsidering at the biophysical level what it means to see, what the means of sight are. Put as a question: How might we see without (colonized) eyes? Or how might we see with all our senses and more at the same time?

To come back to glitter. In the opening scene of Hiroshima mon amour a concoction of dust, soot, and glitter falls quite magically over what we later learn are two bodies embracing, grappling in the dark. Given the weight of the film’s title, we can infer that this moment invites an allegorical reading: the dust is perhaps from the nuclear bomb dropped there, or at least from its psychological afterlife. This allegorical approach is the typical one. As the two lead characters get to know each other following their night of initially anonymous yet embodied passion, their fraught, unraveling relationship, with all its love, pain, and separation, offers a means to process, at a human scale, the nuclear bomb and its monumental, abstract violence. In this way, the film attempts to redress what Gunther Anders has described as the incommensurability of the bomb: our human incapacity to have a felt relationship to the apex of Total Violence.{16} In particular, the flash deaths of 80,000 people in the first split second of the explosion—this is well beyond our empathy: we have not the capacity to feel guilt, sadness, remorse, or sympathy for such a large number of exterminated people.{17} Anders states, “We must strive to increase the capacity and elasticity of our intellectual and emotional faculties, to match the incalculable increase of our productive and destructive powers.”{18}

As the film unfolds, the pained psychology and history of the lead female character are brought to light. The enduring and inescapable trauma of war is seen to reckon with and wreck relationships. The fleeting amour of the title evaporates by the end of the film, only a few miles from ground zero, and only a few years from her initial trauma, perhaps conflating or at least constellating the bomb and the death of her past lover. The film and its love story fail to end in union, a long way from where they began; the couple part ways, distraught and heartbroken, never to see each other again. This marks the impossibility not only of reconciliation—of East and West, man and woman; of the universal human and its own impulses—but also of any kind of repair (what is love?) downwind of the atomic bomb. This tragic ending can’t help but corroborate Anders’s analysis that our humanity, our empathy, and our universal love in their current state are not enough to banish our predispositions toward cruelty, violence, and predation—all of which reach perfection in the bomb. In other words, universal humanism (and with it, today’s genre of the human, including our anatomy and our nature) is entirely insufficient to face the task at hand.

The film does, albeit briefly, invite a constitutional reimagining of the human, one that goes well beyond psychosocial, cultural, and even epistemic reformation. But to get there we have to consider the film backward. It is precisely the process of identity formation, the characters getting to know each other, that causes them to drift apart. That is, as they become more fleshed-out characters with identities tied to place and history, emotions and psychology, and as we the audience also begin to identify with them, completing the intersubjective trajectory (and limits) of traditional narrative cinema, their union becomes more and more thwarted. The more we get to know them, and they get to know each other—the more they fill out their subjectivity—the further they drift apart. In other words, to read the film from our current moment, global harmony (not to mention solidarity) at the level of identity is pure fantasy, a fetish, a distraction, and ultimately a neoliberal ruse par excellence.

Had the film ended where it began, in a cloud of haptic glitter, in a sensual, dusty, indeterminate embracing, we might begin another film, one that reimagines the human without recourse to identity formation, embodied sovereignty, psychology, and the personalization of politics that is, dare I say, the futile yet profitable endgame of subjectivization, of living out one’s full subjectivity. To come back to Anders’s proposition, and to make a slight correction, it is not emotional or psychological incommensurability with abstract violence that is our shortcoming; if it were, then narrative and identity-based processes—or, in Anders’s words, “spiritual exercises,” or perhaps films like Hiroshima mon amour—would have resolved the insistence of human violence a long time ago. Rather, our incommensurability is less a question of “spirit” or psychological renovation, and more a challenge to reimagine our flesh, our cellular sensibilities, our quantic predispositions: the vast set of unknown or unacknowledged collective sensations that only later reduce and separate into emotion, presentation, narrative, and embodiment, becoming the material of identity and its formation. Locating the need for mutation, instead, here in the flesh and in the quantic dissolutions of sovereignty—this forestalls the classic process and movement from embodiment to expression to identity that is reification par excellence, as determined, reproduced, and captured through capital. This process began with the slave on the auction block, remembering here that the slave’s identity was the individuating basis of their valuation, and its ongoing cultivation a mode of perennial extraction—defining much of the contemporary moment.{19} Instead of becoming such subjectively full humans, perhaps we need to stay with the glitter.

The sooty glitter helps us refuse the hail, whip, and dollar that create subjects, fuller subjects, fuller identities (read: more exchangeable commodities, more embodied value). The glitter does something else: it makes a different world available, or at least a different human possible, one that is not overdetermined by the long legacy of the colonial project, one whose identity is not cultivated with techniques developed through the slave trade and its marketplaces. As the glitter falls, it catches the spotlit rays and sends the light scattering; crystalline in form, it diffuses, refracts, and merges the various straight rays of light it comes into contact with, falling gently, perhaps even bending light against the laws of physics. The glitter, with its crystalline optics, does something quite different to light than the lens regime, and therefore it does something quite different to the very basis of knowledge and its optics.

This crystalline optical-otherwise not only affects the mode in which knowledge happens—providing, for example, more refraction than clarity, more diffusion than reflection, to substitute metaphors (epistemology). It also helps us reimagine our flesh, our ontology and biology, the means by which we see, so that we may begin to see without eyes and their innate predatory disposition. Light, especially red light, enters deep into our body, through our skin. In this way we do see/sense with our skin and flesh, we can feel light; photons are matter. This feeling of light does not proceed in the same way as it does in our eyes; no identical images of the world are captured, no abstraction is mechanized, no mind is glamorized. No, the way our skin processes light is not through lenses and mirroring (identification, abstraction, mind projection), but rather through the protein crystals in our layers of flesh and skin; instead, a scattering, fusing, prisming haptic-opticality happens. The falling glitter on the hugging bodies is a mimesis of the way our skin crystals handle and hold light. Touch will always be a process of dusty diffusion, a sensing against sovereignty. This means we see with our skin just as we embrace another, melting into their, or rather our, physicality. We feel light unbind our individual thresholds, our separability, as it scatters, diffuses, and refracts through layers of flesh, through protein structures, through epidermis, tissues, and cells—the sun glowing warm across and under your dimpled cheeks, an interplanetary caress right through to our deep flesh.

Title video: Soot Breath // Corpus Infinitum (Arjuna Neuman and Denise Ferreira da Silva, 2020).

{1} The neonatal synesthesia hypothesis describes the sensorium of all babies as a montage, a mélange of senses “without specificity,” which we unlearn and compartmentalize as we mature. See Ophelia Deroy and Charles Spence, “Are we all born synaesthetic?: Examining the neonatal synaesthesia hypothesis,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Review 37, no. 7 (August 2013): 1240–53.

{2} For more on heat transfer see the film Soot Breath // Corpus Infinitum (Arjuna Neuman and Denise Ferreira da Silva, 2020); and Denise Ferreira da Silva, “On Heat,” Canadian Art, October 29, 2018.

{3} See Aristotle: “Now sight is superior to touch in purity.” The Nicomachean Ethics, trans. David Ross (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 191. Or, again Aristotle: “Of all the senses sight best helps us to know things, and reveals many distinctions.” Metaphysics, trans. Hugh Tredennick (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1938), 1.980a. Elsewhere, to begin his Dioptrics Descartes states that “the entire conduct of our lives depends upon our senses, among which that of sight being the most universal and most noble, there is no doubt that inventions which serve to augment its power are the most useful which could exist.”

{4} By Modern Knowledge I am referring to the vast edifice of post-Enlightenment thought, its Eurocentrism and role in ongoing colonization, hence its capitalization as a proper noun. This is a reference to Denise Ferreira da Silva, whose work contends with Modern Knowledge’s enduring violence. See Ferreira da Silva, Unpayable Debt (London: Sternberg Press, 2022).

{5} For common examples of this critical approach as it appears in decolonial and visual studies alike, see Fred Moten, Black and Blur (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), in particular his writing on Charles Gaines; and Harun Farocki’s film Images of the World and the Inscription of War (1989). See also Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, trans. J. A. Underwood (London: Penguin Books, 2008); and Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle, trans. Ken Knabb (Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2014).

{6} For examples of this turn in art and theory, see the work of the Black Quantum Futurism Collective; and Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007).

{7} See Luke Willis Thompson’s Autoportrait (2018) for a prime and institutionally lauded example of such substitutions that do more to hide than restructure. This is not to mention representation-based critiques of histories of racism—in the simplified sense and logical outcome of including more nonwhite representatives in culture and politics. For example, see Tina M. Campt, A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021). While this, of course, is absolutely essential to a more fair and just society, it fails to address some of the fundamental preconditions that will sustain racial violence in the face and plain sight of racial equality—Kanye West’s support of Trump is too perfect a case in point here, or before that, Barack Obama’s many wars in the Middle East.

{8} This proposed orientation is by no means original. I learned much of it from meeting Hortense Spillers—who in turn has taken up the work of Sylvia Wynter—as well as from my ongoing collaboration with Denise Ferreira da Silva. When I interviewed Spillers, she talked about an Aretha Franklin song she listened to on repeat during the writing of her doctoral thesis. As she shared this memory her body seemed to fill with energy; dancing in her seat despite a recent surgery, she became a touch electric. Perhaps we can hear this in her voice when she talks about what she called the “lesson of the Blues”: the contradiction of positive affect in spite of deep pain, dancing in the face of violence. Her work and thought seems to have embodied this lesson. Such is made possible, I believe, not only as the “lesson of the Blues,” but also as a “lesson of flesh”—where later she tells me that she still writes everything by hand, she feels with her entire body the matter of thinking and writing, the fleshy materiality she feels, even of a full stop. Not only does she feel the force of a singular full stop in a sentence, but also planetary-scale events such as a tsunami on the other side of the world. Such a predisposition to the world, this lesson of the flesh, allows her to understand, think, and feel with less sovereignty, less enclosure but more varied contradiction, working toward a certain collateral or ecological analytic that not only uncovers deep world pain but simultaneously, like the blues, gives reason to dance. We might call her method a shift from the dialectical to the ecological, a method that looks at both causal relations and nonlinear, fractal, or associative relations—a method whose form also functions critically. This essay attempts to share in this approach. For a further example of the influence of Spillers, Wynter, and Ferreira da Silva, see Zakiyyha Iman Jackson, Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World (New York: NYU Press, 2020).

{9} My interview with Hortense Spillers is available here.

{10} In fact, prey and predator often coevolve so that eye placement for both is a relation, just as the patterns on a prey’s body have evolved to evade the visuality of its predators. For humans, our eye placement can be traced back to a hunting primate ancestry. Starting with insects, over time the size and scale of our prey has continued to grow.

{11} Paraphrasing here a talk by Mijke van der Drift: “To change one’s mind, you have to first change the body.” From Mijke van der Drift and Nat Raha, “Multilogics and Poetics of Radical Transfeminism” (workshop, Arika Episode 10: A Means Without End, Tramway, Glasgow, November 24, 2019).

{12} See Juan Manuel Garcia-Ruiz, “2001: The Crystal Monolith,” Substantia 2, no. 2 (2018): 19–25. My interview with Garcia-Ruiz is available here.

{13} Again the language tells this story: The word focus was first used by Kepler in a mathematical sense, then redeployed by Hobbes in 1650 in relation to the mind. Likewise, the word reflection came to be applied to ideas in 1670—both of these follow from Kepler’s death in 1630 to enter the popular lexicon.

{14} What could a decolonization of ontology look like? Perhaps the possibility to mutate otherwise. Studies of synapses in the brain tell us that when one sense is subordinated, such as through blindness, the synapses once used for sight change to support another sense, such as hearing or touch.

{15} See the film Serpent Rain (Arjuna Neuman and Denise Ferreira da Silva, 2016) for an elaboration on peri-acoustics—where hearing from within the womb can remind us of a state where we are more than one but less than two bodies, hearing from without and hearing from within.

{16} Gunther Anders, “Reflections on the H Bomb,” Dissent 3, no. 2 (Spring 1956): 146–55.

{17} Incidentally, this flash was so bright and great it turned streets into cameras, where the outline of bodies blocking the flash left prints all over the cement. Just as platonic solids return in the mechanical architecture of the nuclear bomb, so too does Kepler’s camera obscura. I call these lineages lethal abstraction. For more on the concept of lethal abstraction see 4 Waters—Deep Implicancy (Arjuna Neuman and Denise Ferreira Da Silva, 2018).

{18} Anders, “Reflections,” 153.

{19} See Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).