At the Center of a Thing You’re Absent From

Emma Ben Ayoun with Jordan Lord

An All-Around Feel Good (2024) opens with filmmaker Jordan Lord’s narration, in which they articulate a set of demands of the New York Film Festival, where the film premiered in September 2024. Lord begins:

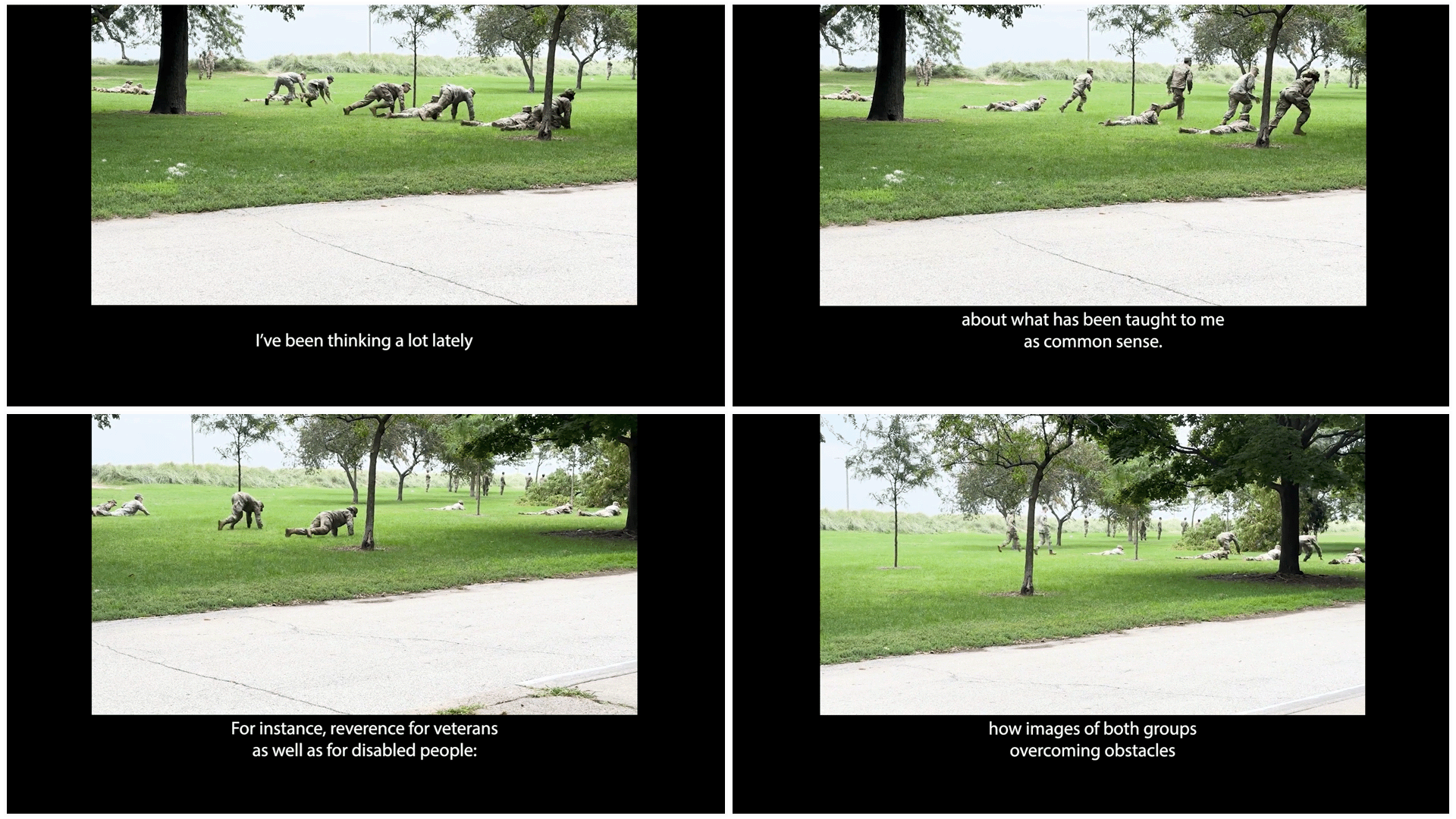

Excerpt from AN ALL-AROUND FEEL GOOD (Jordan Lord, 2024).

This gesture establishes not only the filmmakers’ own political commitments but the film’s specific mode of self-awareness. Rather than acknowledge its mode of production, the film foregrounds its mode of distribution, and as it does so—“Beneath the laurels, captions appear”—it speaks of itself as it plays. This establishes a complex, layered temporality: Before anything “has happened,” as it were, the film summons forth a particular moment in time—early autumn 2024, when the 62nd NYFF took place, almost one year into the genocide in Gaza—as well as its own, split-open present. It expands the borders of the film itself, reminding us that the film object, despite its seeming fixity, is flexible and subject to change, and indeed has a responsibility to change in response to its surroundings.

It also engages multiple audiences in multiple registers, not simply as direct address or as narration but as something in between. Lord uses voiceover and captioning to simultaneously provide image descriptions (a vital accessibility measure) and first-person commentary, with these two modes of address often collapsing into one another. Its adaptability and multiplicity are part of what make An All-Around Feel Good more than just a film about the relationship between disability, representation, and the nation-state. Rather, it transforms into a piece of disability media, an artwork with values of disability justice work embedded into its very form.{1} By disability justice, I refer to the ten principles of disability justice articulated by Sins Invalid, a collective founded in 2005 by Leroy F. Moore Jr. and Patricia Berne. These principles are intersectionality; leadership of those most impacted; anti-capitalist politic; commitment to cross-movement organizing; recognizing wholeness; sustainability; commitment to cross-disability solidarity; interdependence; collective access; and collective liberation.{2}

As I and many others have argued, disability activism has from its inception been wholly bound up with a politics of coalition, emphasizing interdependence and solidarity rather than organizing around a singular concept of disability or disabled identity.{3} To that end, disability justice activism moves beyond a rights-based approach to focus on questions of access—of how institutions and spaces can be continually reshaped and expanded (or abolished) to meet the diverse needs of all who use them. When it comes to media production, then, a disability justice–oriented practice requires active engagement with the historical inaccessibility of the medium—with the ways an able-bodied viewer has long been presumed and privileged by the cinematic apparatus. In contrast with more conventional documentary films that narratively center disability, Lord’s film takes access measures (captioning, image descriptions, etc.) as aesthetically and politically productive tools that should be integrated into the text itself as a way to repeatedly invoke a diversity of spectatorial modes—to insist that there are many ways of seeing, or perhaps sensing, a film.{4}

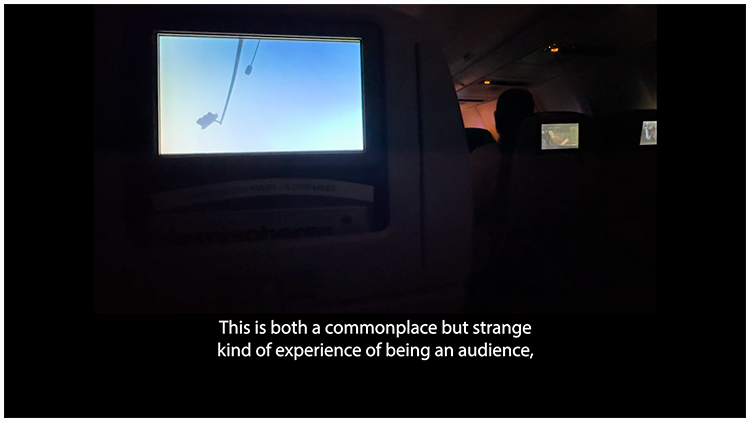

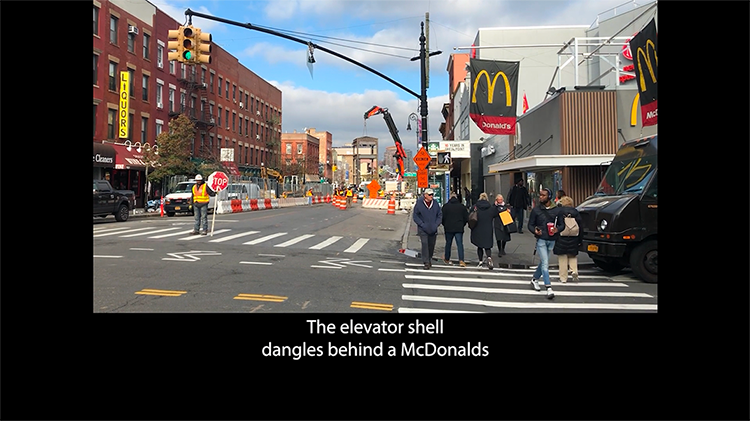

An All-Around Feel Good is essayistic, purposefully meandering, driven by its flow of ideas rather than narrative plotting. At its center is a concern with the ways disabilities have been both ignored and exploited by the American nation-state, the ways that images of disability circulate in service of America’s national project, and, most vitally, the ways that norms and modes of media spectatorship and media access are connected to broader ideas of national belonging and the national subject. The film takes us through a series of seemingly quotidian images from Lord’s daily life (watching films on an airplane, watching a military training exercise in a public park, standing at a busy street corner in Brooklyn, etc.) which reveal some of the ableist and imperialist violences that structure the banal everyday in America, and the myriad ways that images of disability are put to work in service of these violences. Ultimately, the film explores the ideological processes by which ableism and imperialism are made to appear benign and obvious—are transformed into “common sense.” If, as the film’s use of access measures makes clear, there are no common senses guaranteed within an audience, the very notion of common sense falls under suspicion. In what follows, my ongoing reflections on Lord’s work are accompanied by commentary from the filmmaker themselves.

AN ALL-AROUND FEEL GOOD (Jordan Lord, 2024).

AN ALL-AROUND FEEL GOOD (Jordan Lord, 2024).

The invocation of Gaza in All-Around’s prologue echoes through every frame that succeeds it. Jasbir K. Puar, in her prescient The Right to Maim, writes forcefully about disability as a kind of by-product of war and settler-colonial violence in Gaza, noting that while so-called “shoot-to-cripple” policies adopted by the IDF appear “on the surface to be a humanitarian approach to warfare,” they conceal a tactical policy that, in conjunction with the ongoing destruction of medical infrastructures in Gaza and the West Bank, is a way both to keep official death counts low (that is, to make intentional acts of violence hard to prove) and to debilitate populations in order to ensure their future inability to fight.{5} This practice is not, of course, exclusive to the IDF and its activities in Gaza and the West Bank. But considering that “many of the almost 100,000 injured Palestinians in Gaza [as of October 2024] will acquire long-lasting impairments requiring rehabilitation, assistive devices, psychosocial support and other services that are severely lacking,” and that prior to the events of October 7, 2023, 98,000 Palestinian children already had disabilities that made them particularly vulnerable to the effects of war and forced displacement, it is clear that the ongoing violence in Gaza and the West Bank is one of the major mass-disabling events of our current global moment, and therefore not only a human rights issue but specifically an issue of disability justice.{6}

Jordan Lord

To answer your question about how the opening section of An All-Around Feel Good came about, it was conceived as a way of amplifying the message of the open letter that several filmmakers in NYFF and I drafted and signed.{7} For Abby Sun and me, it felt important to think about how the film was being changed by its screening in the festival—which is related to the film’s theme of how disability is put to work—and then to ask how the film might in turn change the moment of this screening.

The intro begins with an audio description of the laurel for NYFF. Because this convention of adding the laurel to the start of a film is meant to both mark an exchange of value and signal that the filmmakers are proud of their inclusion in the festival, and vice versa, it was also an opportunity to think about what’s at stake in claiming and being claimed by an entity that you hope to shame into action but also feel ashamed to be a part of—in this instance, due to their complicity and silence around the genocide in Gaza.

It’s especially interesting that you connected this part of the film to Jasbir K. Puar’s writing, because there was an earlier version of the film that more explicitly quoted her. Much of the film was inspired by trying to contend with her point that the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 was signed into law, uncannily, around the moment that the US entered the Gulf War.{8}

Puar writes of this historical convergence, “The ADA is in part the victory of the long-term activist efforts of war-injured veterans, only to be followed by more warring activities that debilitate populations of the U.S. military as well as civilians in Iraq.”{9} The war machine produces the need for legislation that tackles its effects rather than its causes. And a film that takes disability as its subject without interrogating its form, for all its effectiveness, remains similarly constrained within a structure that can never fully attend to the needs of those it represents.

About halfway through An All-Around Feel Good, the screen shows a group of soldiers doing a training exercise in a public park. There is a gentle comedy here, of these men and women in full military apparel, running and jumping from (or toward) an imaginary threat (and, as the narrator wryly notes, “ostensibly trying not to be seen, although they are in a wide-open green space”). Over their images, Lord narrates, “I’ve been thinking a lot lately about what has been taught to me as common sense. For instance, reverence for veterans as well as for disabled people: how images of both groups overcoming obstacles are intended to make their audiences feel good.” As the scene continues, Lord plays the audio from two promotional videos for Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW). Shortly thereafter, Lord will reference one of the most famous images of disability history in the United States: the Capitol Crawl of March 12, 1990, in which activists made their way up the stairs of the Capitol building, many with great physical difficulty. As Lord says in the film, “This created an image problem, which the nation-state sought to resolve by naming disabled people as Americans first.” The ADA was formally signed into law four months later. And so an interesting opposition subtly takes root—between the soldiers-in-training who crawl to avoid being seen, and the disability activists who crawled precisely in order to be seen.

JL

Disabled people and veterans (and then disabled veterans) often share this status of having their lives used as representational material that does not situate them as the audience for what is being represented (which is then confirmed through the lack of access features in the use of this media). In the type of nationalistic media I’m reproducing in the film, they are figures in whose image appeals are being made, rather than audiences who are being appealed to. Or, if they are being appealed to, it is to share in the compulsory feel-good affects, which screen out other possible feelings or questions about how these images are also forms of exploitation or ableism in themselves. I feel like the flip side to this is the way that national belonging is a form of being an audience that places you at the center of a thing that you’re also absent from. You’re asked to watch but not participate, or participate only to the extent that watching is not disruptive to the plan.

There is an inherent paradox to the emotional exploitation of those who are represented as vulnerable: a fantasy of understanding and connection, of shared humanity, that is also predicated on a sustained feeling of difference, of distance.{10} And the question of what disability is, and looks like, is itself fraught. In her 2008 article “Disability Images and the Art of Theorizing Normality,” the sociologist Tanya Titchkosky considers the ways that “disability is made, made between people, in our imaginations and is always steeped in the cultural act of interpretation.”{11} She continues:

We need only think of the bombings of various nations in order to recall images of blown-off faces, missing legs, and broken backs, where the seemingly obvious disability sign—wheelchair—does not even enter the picture. But even if we do not think about war’s number one product, which, according to the United Nations, holds a ratio of at least three to one of disability (three) to death (one), still, we must think of personal locations, social situations, and political contexts if we are to think of disability. Every image of disability is an image of culture.{12}

“Images of disability,” per Titchkosky, take on several forms: the pure abstraction of the wheelchair symbol; the utter specificity of individual disabled people, subsumed in this case into the flurry of images that follows acts of war; and the blurred space in between both of these polarities in which disability as a concept of the imagination resides. And even those images that might be deemed “specific,” such as that of the disabled veteran, are by their very nature ambiguous. They reveal neither the individual’s history (the personal and political events that may have led to their impairment) nor their present (psychological trauma, physical pain, and the socioeconomic conditions that determine how a disability is lived). This makes the disabled body particularly pliable and potent in the hands of power: These images can be endlessly reframed—as tragic or as inspiring, as inevitabilities or as aberrations.

JL

I was thinking about the case of one of the VFW videos that does double duty as inspiration porn about supporting veterans and about employing cognitively disabled people. Inspiration porn is another term for putting images of disabled people to work affectively, often used by charities seeking to raise money around disability—and often in the service of ableism. Here, the pornographic convention of a “money shot” is quite literally linked to this idea of feeling good, to the point of inspiring tears and donations.

The second promotional video is a very direct companion to the first, in that they’re both explaining who does the work behind Buddy Poppies, these synthetic flowers that are used as a fundraising tool for the VFW. It’s based on an old-fashioned idea of fundraising through small donations, in exchange for a small token. This first video’s feel-good is supposed to stem from the idea that the Buddy Poppies are assembled by volunteer labor that anyone who cares enough can do while doing other things like watching TV. Already this video is disturbing to me, in that it takes it to be self-evident that assembling these flowers is “helping veterans,” is “doing good,” and eventually this is framed as “God’s work.”

The second video, though, explains that the COVID-19 pandemic changed fabrication needs to the point that assembly was instead outsourced to an organization, Cottonwood Inc., that employs cognitively disabled people. The video is primarily shot in a textile factory, and, like the first one, it explains and shows the flowers being assembled. It struck me that we’re supposed to see the employment of these factory workers as charitable, even as what’s supposed to be good here is that they’re doing wage labor (which I want to clarify is minimum-wage labor, as opposed to the subminimum wages that are legal to pay both disabled workers and gig workers that I discuss later in the video).

But I was also really aware of how the video demands (expects? extracts?) from the audience a commonsense understanding that employing cognitively disabled people to make these surplus (or unnecessary) objects to raise funds is an “all-around help.” The images and words of the factory workers are used as proof of the intrinsic goodness of this mission, where all of them are there to comment not on the work itself but on how it makes them feel good, too, because they’re helping “veterans.” Here, disability (and disabled labor) is the ground of both forms of supposed goodness, while also not being named; it’s instead something that the workers and then the VFW as an organization feel good about and that we as an audience are supposed to feel good about, too.

I think the role of imagination (and how image description elicits imagination around an existing set of images) here is about trying to wrest back some agency over the ways in which the American cultural imaginary around disability, war, and veterans has been so overdetermined by a certain set of compulsory affects (the feel-good, the inspirational, the sentimental, on the one hand, and the tragic, on the other). It’s also about trying to open a space where there’s a gap between what media (like that produced by the VFW) wants you to feel and what you actually feel.

In many ways, the whole reason I wanted to make this film was to ask how we might watch these promotional videos with an audience, against the grain of how they were intended to be consumed. By mediating them through disability access like description, I also wanted to ask what it means for that audience to privilege the presence of disabled audiences, who might feel differently about what we’re watching.

AN ALL-AROUND FEEL GOOD (Jordan Lord, 2024).

AN ALL-AROUND FEEL GOOD (Jordan Lord, 2024).

By evidencing nothing and yet, due to its privileged relationship to the imagination, appearing to evidence something, the “disabled body” can be conscripted into any number of ideological-evidentiary projects, concealing its own ideological function by virtue of the irrefutable materiality and seeming obviousness of the body—in other words, through the appeal to common sense. In Investigative Aesthetics, Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman offer up the notion of the “investigative commons” as a way to name the “community of practice that arises around the process of evidence production”: the documentation, organization, and dissemination of evidence as such.{13} In this way, the production of evidence is neither the dilution of some anterior, crystalline truth nor a journey toward perfect revelation, but rather a “collective and diffused mode of truth production” composed of multiple distinct but imbricated voices.{14} The investigative commons, Fuller and Weizman continue, might in fact also be understood as common sense:

The formation of common sense can be seen as a mode of creation, the ongoing development of a commonality—built into the creation of knowledge. Indeed, when common sense becomes recognised as a problem of creation, rather than being a repressive set of implicit norms that are taken for granted, it becomes open for reinvention.{15}

Fuller and Weizman here are consciously working against the colloquial use of “common sense” as a kind of universal unthought and instead wondering how exactly practices of investigation and truth production always and necessarily call forth communities of shared understanding—that which appears to “make sense,” that which we tend to call “reality”—even as the sensible and real are constantly being remade and constantly called into question. Understanding sense as something made and common means that however hegemonic our regimes of the sensible may be, they are never absolute. An All-Around Feel Good insists that disability media will be vital to the formation of a more critical and inclusive common sense and not just an example of it.

****

I want to close by considering the relationship of the disabled veteran to the concept of evidence. On the battlefield, the soldier evidences the nation, serving as proof of its power, its numbers, and often its borders; they turn the abstraction of the nation-state into a material reality. The veteran then evidences both war and, by extension, the nation. And the veteran whose body-mind is perceived as somehow having been “marked” by war, bearing its traces (through amputation, trauma, sensory impairment, etc.) while also standing in for the ultimate absence—those killed by war—is perhaps the ultimate deployment of the disabled body as a way of materializing abstractions. Whether disability is understood as the visible manifestation of an inner self, or as the surface upon which are marked the invisible deficits of the external world, or—in the case of the disabled veteran—as a simultaneous signifier of heroism and trauma, it is always imagined as something to be consumed, dealt with, and interpreted from without. That is, it is always imagined as having an audience.

Excerpt from AN ALL-AROUND FEEL GOOD (Jordan Lord, 2024).

And to return to the image itself: The national project (and extensions of it like VFW) traffics in images that are meant to do something to their audiences. In other words, as Lord’s narrator puts it, these images are meant to be “put to work,” much like disabled Americans are meant to be put to work by the ADA, and are put to work by the VFW initiatives Lord describes: to affirm the reality of the state, to make clear what it is and is not, who belongs and who does not, to produce “good feeling” and affirm “common sense.” Disability media, on the other hand, aims to do something to images: to make them work in service of their audiences; to transform them through layers of description and interrogation; to pull them apart and rearrange them. It is the sound-image, rather than the audience, that is understood as susceptible, that is acted upon, transformed. Near the end of the film, Lord says, “Not unlike the illusion of common sense, there are many political positions that appear unrepresentable within the democratic operations of the nation-state and can, for now, only be represented as images, sounds, and the words that bind them.” Disability media offers an alternative mode of representation and a new kind of common sense, rooted not in a nationalist and ableist universalism or even in a call for representation within existing systems of power, but instead in a coalition, a collaborative effort not to locate one true reality but rather to arrive at the politically productive points of convergence across so many distinct experiences of life.

An All-Around Feel Good refuses to offer a tidy ending. In its final moments, Lord—speaking over an image of a darkened silhouette standing on the shore, background sound cut out—cites Dorothy Richardson’s descriptions of early sound cinema spectatorship: “She observes that one of the primary things specific to cinema audiences is the capacity to not pay attention, or to only pay attention to the parts that interest one and to talk through the others, or to shush away these distractions. Here, there’s simultaneously a segregation of sensory access and a dismantling of its meaning, in the fact that the word audience originally meant ‘to listen.’” The audience is both an imagined body and one whose imagination produces the spectacle as such. It is not a politically or culturally neutral space; it can be both inaccessible (in material terms, that is, on the basis of ability, language, class, national origin, etc.) and insidiously imperceptible (as in the notion of “common sense” or the “feel-good”). Lord’s film is both aware of and about its infinite possible audiences.

Title video: An All-Around Feel Good (Jordan Lord, 2024).

{1} See, for example, the dossier entitled “The New Disability Media,” edited by Faye Ginsburg, B. Ruby Rich, and Lawrence Carter-Long, in Film Quarterly 76, no. 2 (Winter 2022).

{2} “10 Principles of Disability Justice,” Sins Invalid, accessed June 11, 2025. Although Sins Invalid is but one of many groups that have advocated for disability justice, the group’s principles, a manifesto of sorts, have been a key text for many organizers since their publication.

{3} See Emma Ben Ayoun, “Cinemas of Isolation, Histories of Collectivity: Crip Camp and Disability Coalition,” Visual Anthropology 35, no. 2 (2022): 196–200; Jina B. Kim, “Cripping the Welfare Queen: The Radical Potential of Disability Politics,” Social Text 39, no. 3 (2021): 79–101; Amber Knight, “Disability as Vulnerability: Redistributing Precariousness in Democratic Ways,” Journal of Politics 76, no. 1 (January 2014): 15–26; and others.

{4} More conventional documentary narratives on disability include Vital Signs: Crip Culture Talks Back (David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder, 1995); Lives Worth Living (Eric Neudel, 2011); Crip Camp (James LeBrecht and Nicole Newnham, 2020); Change, Not Charity: The Americans with Disabilities Act (James LeBrecht, 2025), to name but a few prominent examples. Lord’s accessibility measures in An All-Around Feel Good are in keeping with principles of universal design, defined legislatively by the US General Services Administration as “a concept in which products and environments are designed to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.” “Universal Design and Accessibility,” Section508.gov, General Services Administration, accessed June 11, 2025.

{5} Jasbir K. Puar, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability (Duke University Press, 2017), 129, 144.

{6} See “A Tragedy Within a Tragedy: UN Experts Alarmed by Harrowing Conditions for Palestinians with Disabilities Trapped in Gaza,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, October 25, 2024; Paul Aufiero and Emira Ćerimović, “Interview: Children with Disabilities Struggling in Gaza,” Human Rights Watch, September 30, 2024.

{7} Filmmakers in NYFF62, “Open Letter to the New York Film Festival to End Complicity in Israeli War Crimes,” Screen Slate, September 26, 2024.

{8} The ADA was, in its time, a landmark piece of civil rights legislation that focused primarily on employment discrimination and the accessibility of public facilities such as transportation services and buildings. However, the ADA’s mandates have not been implemented or enforced in many aspects of American life in the thirty-five years since its passage, and many have critiqued its limitations; for example, the Michigan-based Disability Advocates of Kent County describes the ADA as a “bare-minimum compliance framework.” “Why the ADA Isn’t Enough,” Disability Advocates of Kent County, accessed June 11, 2025.

{9} Puar, Right to Maim, 76.

{10} Countless disability activists and scholars have offered important critiques of the “inspiring” image of disability and its privileging of the abled gaze; this form of objectification has been popularly referred to as “inspiration porn.” For a more comprehensive overview of this concept, see Jan Grue, “The Problem with Inspiration Porn: A Tentative Definition and a Provisional Critique,” Disability & Society 31, no. 6 (2016): 838–49.

{11} Tanya Titchkosky, “Disability Images and the Art of Theorizing Normality,” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 22, no. 1 (2009): 78.

{12} Titchkosky, “Disability Images,” 77.

{13} Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth (Verso, 2021), 154. They write, “To think about investigation politically . . . demands a different response in relation to each of the different sites in which investigations are performed: the field, where incidents happen and where traces are collected; the lab and the studio, where they are processed and composed into evidence; and the forum, where they are presented. Each site requires a different level of participation, a different process by which evidence is worked on and socialised.”

{14} Fuller and Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics, 12.

{15} Fuller and Weizman, 155.