Targeted Killing: Ariella Azoulay in Conversation with Miki Kratsman

Text Ariella Azoulay Images Miki Kratsman

A portrait is considered to be the depiction, the representation, the likeness of an individual. The relation between the portrait and its object cannot exist unless someone identifies the depicted person as that individual for whom the portrait stands. A portrait, however, is not only of someone or by someone: it is a complex arena in which different and sometimes contradictory forces come into play. A firm decision or resolve — what we might call high resolution — is needed if one is to stand in front of a portrait and say, “This is X.” Such resolution is difficult to achieve when the visible components of the portrait are poorly rendered, presented in low resolution. The gesture pointing to it and saying, “This is X ” is then hesitant or unresolved.

In our era, excessively rich in technological devices, “taking a photograph” with a camera is just one among many other procedures — such as screen capture or downloading digital files—available for producing images. Low-resolution portraits in the form of blurred impressions are often created without the physical presence of the portrayed individual, a product of the technological features that allow the viewer to single out an individual from a crowd, to foreground her or him by encircling the face or body in an oval frame or pointing to it with an arrow indicating, “This is X.” The resolution involved in transforming these unrecognizable impressions into identified portraits is achieved not by increasing the clarity of visual details but rather by a combined effort of different observers and agents who manipulate and decipher the visually encoded information and identify it as the portrait of X. Similarly, information contained in a high-resolution portrait of an individual can be obscured and made unrecognizable when the person photographed is captured under what I suggest calling “the resolution of the suspect.” Singled out, taken out of context, she or he no longer appears as an individual but rather as an outsider, a threat, presented as encapsulated information that can be acquitted—if at all—only through systems of detection programmed by a specific military logic.

Lifting a camera is a very violent act. The camera hanging on your neck or shoulder is reminiscent of a Hitchcock film—soon we’ll use a weapon. This is how one wordlessly obtains the agreement of whomever is being photographed. The act of lifting a camera is very violent, and every time anew I feel like skipping it. It has many answers. Here I go exposing you. Here I go looking at you. When you ride a bus, you notice the gaze of whoever looks at you. Few people have the guts to still keep looking. Here I am like someone on a bus, telling people that I do not lower my gaze. And through the camera yet, which makes things even easier.

—Miki Kratsman {1}

****

Interview

Uncharacteristically for the general body of Kratsman’s work, in this photographic series one could say he managed to skip this act of “lifting a camera” and in return being seen pointing that camera at someone, seen looking at her or him. He achieved this by choosing to photograph Palestinians from hundreds of yards away, with the photographed persons usually unaware that he was there.

Ariella Azoulay

Is this in fact the first time that the Palestinian is not at all your partner, is even unaware of the situation in which you photograph him?

Miki Kratsman

He could not be my partner. This project requires distance from him. One could look at it and say, “You pretend to be a soldier.” And my answer would be, “Yes, I am a pretender.” When I pretend to be a soldier, I am an “undercover soldier.” And as such, I cannot be a Palestinian’s partner.

AA

In all other situations, the Palestinian has always been your partner. Even when the soldiers covered his head, you acted as someone who keeps his contract with him. And here you carry out a kind of small research endeavor of your own, whereby you actually, as it were, turn your back to the Palestinian?

MK

This photograph could only be taken while the Palestinian did not know I was photographing him. No collaboration could take place here. Nor do I communicate with him, or even maintain eye contact.

AA

Still you are not the soldier, nor do you wish to be. So can one assume that even if certain clauses of the contract between you and the Palestinian are not kept, other elements are being maintained in a way that distinguishes you from the soldier? What are they?

MK

Due to my long-lasting relations with Palestinians prior to this project and subsequent to it, I felt I could produce these photographs. This gives me some moral right, let’s say, not to include them as partners here.

AA

You trust them to trust you?

MK

Yes, out of some common bond we have.

AA

What would you do if a Palestinian were to see you, standing close to you but outside the distant field of vision of the lens?

MK

There were Palestinians who saw me photographing and gave me strange looks. I think they thought I was some kind of construction inspector.

AA

Who would come to demolish their home because its construction was illegal, etc. . . .

MK

I take this picture from my work place at Bezalel (Academy of Arts and Design). I arrive wearing a shirt, ready for class. I don’t look like a press photographer, but rather like a clerk. I don’t even carry a photographer’s case. I leave it in the car.

AA

And you continue?

MK

It was unpleasant. Often when I got such a look I stopped photographing for that day and came back another time. I felt it was pointless to stretch it out. I took photos this way for a long time, about a year. It’s not easy to catch people this way. One can find moral fault in nearly every work of this type, and you can’t come clean. I don’t want to do work that takes no risks. It’s terribly degrading.

There is a long tradition of colonial photography of persons subjugated and exploited by the very group to which the photographers belonged. This has engendered a critical discourse that regards photographs taken under such conditions as relatively simple expressions of the unequal power relations between those who controlled the means of representation (the camera) and those who became the objects of that representation (the subjugated). But photographs are not representations.

Recent revisionist histories of photography have emphasized the participation of photographed persons in the photographic event, in a way that makes obsolete the idea of photography as an expressive tool in the hands of the photographer who used the photographed subjects as his raw material. It is still commonly expected of those belonging to the occupying, colonial, or exploiting side to retreat and make room for those who were exploited, allowing the latter to speak in their own names and tell their own tales. After years of oppression, dispossession, exploitation, and exclusion, it seems this has become an aspect of necessary affirmative action.

I would argue the opposite. History cannot be so neatly partitioned, and the cruelty of governing peoples differentially should be accounted for in common narratives, not reproduced as if victims and perpetrators live on separate planets. The resulting warped histories have enabled the rise of a whole realm of narrative about those who became oppressed minorities from which the perpetrators of oppression are often absent. It is as if dispossession and oppression were produced without agents who should be confronted with their deeds and made to account for them. Perpetrators hardly appear in such histories, either as objects of research or as researchers and agents of change who might exert their right to abandon the position of perpetrator and instead collaborate with oppressed groups in demanding to change the rules of the game. Those rules, inherited from perpetrating ancestors who created the colonial reality of oppression, continue to shape our world today.

The implications here are obvious: Palestinians, and those Jews who oppose the Zionist regime and narrative and policies such as the perpetuation of Palestinian expulsion, participate in reconstructing the common ground from which non-Zionist narratives can emerge by depicting Zionism from the point of view of its entire population, starting with its victims. Such narratives begin with Edward Said’s ground-breaking essay from 1979, “Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Victims,” followed by Ella Shohat’s “Sephardim in Israel: Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Jewish Victims,” which depicts the narrative of the dispossession and oppression of Mizrahi Jews by the same regime. These narratives tell the story of the dispossession of Palestinians as the major event in the implementation of the Zionist regime in 1948.{2} The Nakba, the term used as early as 1948 to describe the ruination of Palestine and the expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland, cannot be written as an exclusively Palestinian history. Only once it is acknowledged as an essential part of the history of Jews living in Palestine (and, after 1948, in Israel) can one hope to change the political framework that perpetuates the consequences of the Nakba and continues it in other ways.

In like manner, Kratsman’s photographic confrontation with the Israeli gaze—that of the occupier in general and of the soldier in particular—can be read as part of our understanding that the history of the Occupation begun in 1967 cannot be told either strictly from the Palestinian’s point of view or out of identification with it. The circumstances under which the Jewish Israeli’s gaze has been constituted and replicated through the years must be deeply examined. Kratsman’s project, which risks repeating the soldier’s instrumental gaze, illustrates the extent to which maintaining a critical distance from the usual position of the Jewish Israeli partaking in the Occupation is a necessary, but certainly not sufficient, condition for partnership with Palestinians—for creating alliances, building shared archives, researching visual space, and imagining a different future. Replication of the instrumental gaze through photography, in a way that is not followed by a violent action, is part of a process of undoing what has become nearly second nature: seeing the Palestinian under the resolution of the suspect merely because he or she is Palestinian.

AA

What makes you want to experience the soldier’s gaze, to simulate turning the Palestinian into a suspect?

MK

Reading the image I produce when I experience the soldier’s gaze interests me more than its actual production. I am interested in the soldier who has to read the image, who has to say “it is he” or “it is not he,” “it is now” or “it is not now,” “click” or “do not click.” I am interested in an image that produces immediate action, not an image that lets one wait, move away, and come back later. It is a kind of image of a decisive moment. It is not a decisive moment regarding the act of photography, but rather regarding what is to be done with this person: is it or is it not he, is he inside the car or not, are there people around him who might get hurt or not, is he to be killed or not? Presumably, on most occasions when cars are targeted, the soldiers know that the driver is inside the car but do not see him. That is the moment that interests me.

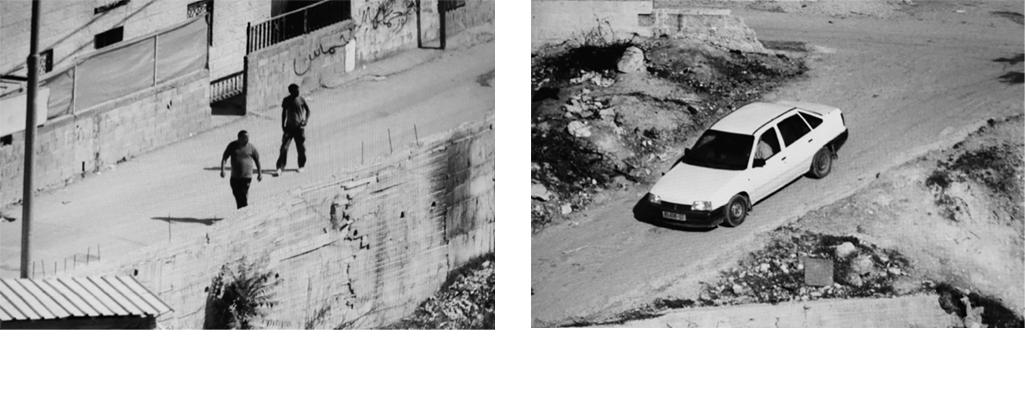

This series of black-and-white photographs examines the capacities of the medium to create the ultimate suspect out of the technology and makes us face the ease with which we can participate in turning each moment in a Palestinian’s life into a suspicious one, thereby transforming the Palestinian into a target of justified killing. The technologies used by the army to collect remote information about Palestinians (and then to execute those it has designated) are a combination of popularly available technologies and other specific professional developments, information about which is incomplete and somewhat vague. In this series Kratsman seeks to image the way in which the Palestinian appears on the various screens used by the military at the decisive moment preceding targeted killing. The photographs were taken from his place of work at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design on Mount Scopus in Jerusalem. Topographically, this viewpoint overlooking the Palestinian village of Issawiya embodies the spatial power relations common to the possession and control of land in Israel and the Occupied Territories.

Positioned at his window, Kratsman installed a type of lens commonly used on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), whose focal length greatly exceeds that of a “normal lens” used for street photography (about 1000mm versus 50mm). The combination of altitude and lens allowed him to remain invisible as he erased the hundreds of meters’ distance between himself and the persons he photographed. At this remove, these individuals easily become “suspects.” One photograph shows a woman walking (see p. 123); another, a place that looks like an abandoned construction site (see p. 124); and a third, a man either disembarking from or climbing into a car (see p. 125). The photographs dissolve the ne line that separates the Palestinian’s full existence as a human being and turn him into a wanted man, an object of targeted killing.

Unsurprisingly, since technology can turn a full existence into a unit of information, many of the photographs Kratsman created resemble verbal descriptions found in various documents describing targeted objects. A description of a gure holding a weapon could apply to several of the photographed persons: someone who happened to be holding some insignia cant object, a construction worker holding a pipe that suddenly looks like a shoulder-mounted missile.

AA

Your choice of a UAV lens in the context of research for targeted killing is understandable. But how did you choose your subjects?

MK

I photographed everything: anyone or anything moving in the street. I ran an Internet search for information on the targeted killings. I wasn’t interested in what kind of weapons were used but rather in what situation the person was in when shot, where he was, what he was doing at the time. The choice of frames was made accordingly. I wanted them to suit existing narratives of killings. Thus, for example, according to testimonies of people whose window was entered by a missile while they were at work, I photographed the window of an office building. In another instance, I tried to photograph someone who was holding something that looked like a weapon but was not a weapon. When I read the testimony given by the widow of Dr. Thabet Thabet, shot while coming out of his house heading to his car, I suddenly recalled a photograph I have of someone getting out of a car.

AA

Did you use only information of the Israeli-Palestinian context?

MK

No. There are, for example, these two people walking down a street. It reminded me of a photograph of a killing in Baghdad. My photographed persons were walking just like them. Elsewhere I read the testimony of a woman who (based on the long-range photo image) could have been a man.

AA

How distant are you from the photographed parties?

MK

I can’t estimate with any certainty, but something between 800 meters and one kilometer. What you see in the photos is not something you could normally see with your bare eyes.

AA

If the soldier were near you, would you dare lift such a sizable lens?

MK

Yes. I don’t care if an Israeli soldier comes and asks me why I’m photographing. I have been in more complicated situations with soldiers.

AA

When you lift such a lens, do you not feel threatening, threatened, as if you are doing something that could get you in trouble?

MK

Yes, I do have a sense of doing something problematic. It’s the rst time I felt that wielding the camera resembles wielding a weapon.

AA

I recall interviewing you for my film The Angel of History in 2001. You said that for you, holding a camera is like holding a gun. . . .

MK

Here the sensation is much stronger. There is nothing closer to shooting than aiming the lens from such a distance at a single person. It’s like a telescopic sight on a rifle; only the crosshatch is missing. It’s a different perspective than the one I’m used to while taking photos. A totally different field of vision.

AA

In what way?

MK

The area within which you photograph is extremely narrow. The slightest movement of the lens makes you lose the person. The perspective is very flattening, and whatever is in front and in back gets very confused. That’s what a long lens does—it flattens things terribly. I increase this even more afterwards, when I photograph all these photos again from a screen. I want to enhance even more the sight that the soldier faces when he decides. In this context I am less interested in what the soldier sees when he photographs. (Instead,) I try to get close to the picture that the soldier looks at as he decides whether or not to kill.

AA

Are you sure these are two different soldiers—the one who photographs and the one who looks and decides?

MK

I don’t know. Perhaps they’re the same one.

The use of a UAV lens that serves in a targeted killing enables one to reconstruct what a soldier sees while making the decision to eliminate someone. The soldier is assisted by preexisting information about the wanted man, which is supposed to turn a frame like those in this series of Kratsman’s photographs into the last link in a chain of information collected from various sources, which together empower the soldier to make the decision to execute the wanted man. From a civil point of view, such “information” should be rejected out of hand as the basis for deciding to execute someone. If there is truth in such information, a case to be made, it belongs in the judicial system, which is supposed to handle it just as it would information about any other citizen. Information isolated through the lens of a UAV, whose very focus places the subject in the resolution of a suspect, should not be used as evidence for an in-the- field court martial resulting in execution. Kratsman’s use of such a lens, even apart from the ideological apparatus that presupposes the Palestinian to be suspect, reveals how perfectly the technology acts and reinforces the ideology.

The question of whether or not the Palestinians seen through this lens are “suspect enough” is answered by Kratsman’s use of additional procedures to ne-tune the precise image of the ultimate target: black-and-white photography, scanning of the image, projecting it on a screen, and rephotographing it from the screen. Each of these procedures intensifies the conclusion that in order to appear as the ultimate target, the photographed person must be designated a priori as a suspect. Technology provides a seemingly objective framework for his or her appearance, but this series exposes the extent to which the control achieved from the position of a “fly on the wall,” the invisible eye, conceals the fact that the judging eye is activated by a technology that makes the Palestinian “sufficiently suspect.” Even if the processes used by Kratsman to produce these photographs are not identical to those used by the army, the images he created make the places, situations, and photographed persons look like abstract units of visual information: they have lost their specificity and unique character through a series of distancing, alienation, mediation, and replication processes.

{1} From a conversation with Miki Kratsman recorded in the film The Angel of History, directed by Ariella Azoulay (2001).

{2} Mizrahi Jews or “Oriental Jews” are those descended from local Jewish communities in the Middle East.

Text and photographs are reproduced by permission from “I. The Lethal Art of Portraiture” and “Targeted Killing” from Miki Kratsman, The Resolution of the Suspect (Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum Press and Santa Fe, NM: Radius Books, 2016) © 2016 by President and Fellows of Harvard College. Text © 2016 by Ariella Azoulay. Images © 2016 by Miki Kratsman. Courtesy Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.