talking about it is also resistance \ The Interview as Form and Force

Farah Atoui and Cynthia Kreichati

untitled part 1: everything and nothing (Jayce Salloum, 1999–2001) is available to view in its entirety here.

****

In the spring of 1999, the artist Jayce Salloum interviewed the freedom fighter Soha Bechara in her small dorm room in Paris, a recorded conversation that would eventually become the material for Salloum’s untitled part 1: everything and nothing (1999–2001). Salloum had met Bechara a few nights prior during a screening of his film Up to the South (1993) and had reluctantly asked her over dinner whether he could film her. In the year since her release from the infamous Khiam prison, where she was held for ten years (six of which were spent in solitary confinement) for the attempted assassination of Antoine Lahad, the leader of the collaborationist South Lebanon Army (SLA), Western and Arab press had interviewed her relentlessly, inquiring about the details of her life under occupation and the horrid conditions of her captivity. While Salloum was initially ambivalent about taping Bechara, not wanting to reproduce the media’s extractive approach, the connection he struck with her swiftly chased his hesitation away. Reflecting on their first encounter, Salloum observes that they got along well. “So I succumb and ask,” he concedes, before adding, “She thinks it’s no big deal and invites me for breakfast the next day.”{1}

In grounding their encounter in the ordinariness of her student room, Salloum is perhaps trying to demystify the exalted figure of living martyr that other journalists and filmmakers had ascribed to her. He asks Bechara how she feels about “all this attention, all these questions, all these requests.” She answers by describing her ethical duty to share her knowledge and her experience to the best of her abilities. She then pauses for a moment, before declaring, “Resistance for me is a mission, and part of this mission is the talking about it.” Given the conditions of its production, untitled part 1 isn’t just any interview. It is driven on one hand by Salloum’s refusal to engage, reproduce, and amplify reified media discourses, and on the other by the serendipity of an encounter, and the artist’s interpersonal affinity with the freedom fighter. Bechara’s invitation to talk about it—indeed, her insistence on the militant invitation to make oneself heard— is the starting point for our own inquiry, nearly three decades later, into the political affordances of the interview. How might the interview—what Salloum has referred to as “the art of conversation”—function as a form of, and force for, resistance in times of crisis? What, if anything, is the power of talking about it in the face of Israel’s attempted annihilation of the Palestinian people?

UNTITLED PART 1: EVERYTHING AND NOTHING (Jayce Salloum, 1999–2001).

UNTITLED PART 1: EVERYTHING AND NOTHING (Jayce Salloum, 1999–2001).

This collection of short essays takes up this question to consider the interview’s role within and beyond cinema, as well as its intersections with other cultural and political practices, to understand its possibilities and limits in the present moment. How do we attend to Bechara’s call to talk about it against the backdrop of genocide? Contributors Dyala Hamzah, Paige Sarlin, Chantal Partamian, Hend Ben Salah, Léa Chikhani, and Claire Begbie each examine, through diverse disciplinary lenses and vantage points, how the interview mediates and transforms one’s relationship to political struggle. They take it up not only as an artistic and narrative form but also as an analytical device, interrogating the fraught connections between discursive practices and political action. Their perspectives resist the impulse to reconcile this tension, preferring to recast its antagonisms into ongoing sites for critical and political inquiry. Grappling with contradiction, we hope, can itself become a form of action: one of many small, partial gestures that together build collective resistance. As the poet Diane di Prima once remarked, “NO ONE WAY WORKS, it will take all of us / shoving at the thing from all sides / to bring it down.”{2}

Throughout the years, our respective engagements with Jayce Salloum’s work, whether as scholars, programmers, or as members of collectives engaged in a political practice of art, have allowed us to deepen and expand our reflections around the epistemological and political potential of the interview. The first time we worked with Salloum, we presented untitled part 1 alongside other works that traced long-standing histories of uprisings, from Iran to the Maghreb, part of Making Revolution: Imagined Histories, Desired Futures, a video exhibition we curated with Viviane Saglier for Montréal, arts interculturels (MAI) in 2021. Bechara’s resolute commitment to resistance, we thought, disrupted presentist narratives that cast the “Arab Spring” as a singular ahistorical moment of revolt in the region and reminded audiences of the enduring legacies of earlier, unfinished struggles. As we prepared to install the works, we received a set of meticulous installation instructions from Salloum. His insistence on the conditions through which his interview with Bechara should be experienced was a direct aesthetic and political intervention. He wanted viewers to be able to really sit with Bechara’s words; he wanted to create the potential for a meaningful space of relation inside the gallery.

With specifications on light, height, seating, and wall color, his directives delineated the terms of the work’s legibility, guiding how people paid attention, how they listened, and how long they stayed with the piece. By placing the viewer comfortably in an intimate space, and at Bechara’s eye level, Salloum cultivated an intimacy that transformed the act of viewing into a practice of engaged listening and an encounter structured by attention and care. Viewers were brought into presence with Bechara—a proximity that, as Partamian reminds us, constitutes a form of political praxis. Through Salloum’s careful staging, the immediate, embodied experience of the installation added another layer to the historical moments the film condenses and the meanings which accrue around it—from Bechara’s release from Khiam prison in 1998, to her meeting with the artist in her Paris dorm room, to the time of viewing. Every personal and historical moment appeared to be different. Untitled part 1 folded multiple spatial and temporal frames into one another, each inflecting the work, generating resonances, and reconfiguring the interview’s affective charge and its political potency under shifting conditions of struggle.

Salloum’s reworking of the genre, conventions, and epistemic functions of the interview, we suggest, unsettles fixed binaries between interviewer/subject, expert/witness, and artist/militant that often undergird the ideal interview form. In disrupting these epistemic hierarchies, his filmmaking turns the interview from a mode of representation into a practice of relation that desires to enact the very politics of resistance and solidarity it seeks to document. In this sense, Salloum’s work exposes the interview’s double nature as both a cultural form embedded in power and a site from which unequal relations can be renegotiated. Here, the interview form, galvanizing political force, becomes a testimony, gesture of solidarity, historical record, or site for revolutionary possibility.

Our most recent engagement with Salloum’s practice, and the catalyst for this publication, grew from that recognition and from our desire to explore how his interview with Bechara continues to take on new urgency and significance in the context of Israel’s ongoing campaign of genocide in Palestine and systematic killing and destruction in the region. Convinced that the current historical pressures reenliven the work’s force, we screened untitled part 1, part of talking about it is also resistance, at Montreal’s Cinéma Public in March 2025. The film program was organized in collaboration with Regards Palestiniens, a Montreal-based collective whose curation Begbie describes as an approach fostering political learning and public conversation. The screening concluded a broader workshop (co-organized with Razan AlSalah) that sought to grapple with the challenges and political potential of creative expression in the face of total devastation. Salloum’s long-standing relational approach to artistic creation served as a guide for the curation of both the film program and the workshop. If, as Ben Salah observes, his practice moves from heavily montaged works to the interview form, it also reflects Salloum’s growing commitment to Palestinian liberation, Lebanese resistance, and Indigenous land rights in North America, and foregrounds the renewed urgency of transnational solidarity in this moment.

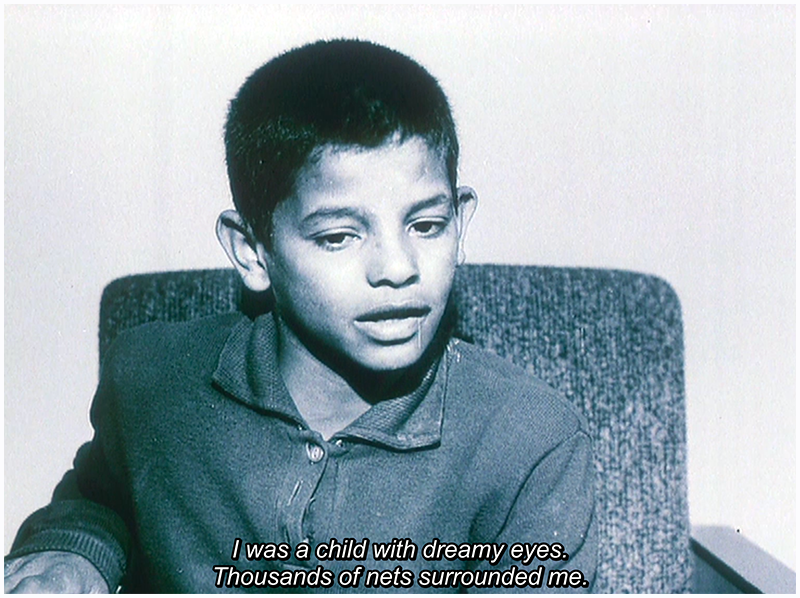

FAR FROM THE HOMELAND (Qais Al-Zubaidi, 1969).

FAR FROM THE HOMELAND (Qais Al-Zubaidi, 1969).

Alongside untitled part 1, talking about it is also resistance brought together three other short films structured by interviews with people engaged in anti-settler-colonial struggles: Palestinian children in a camp in Syria in Far from the Homeland (Qais Al-Zubaidi, 1969); Abdel Majid Fadl Ali Hassan, a Palestinian refugee in Lebanon, in untitled part 3b: (as if) beauty never ends . . . (Jayce Salloum, 2000–2002); and Cleo Keahna and Terry Running Wild at Standing Rock in Dislocation Blues (Sky Hopinka, 2017). The program prompted diverse questions about cultural work and political mobilization, and more specifically about the interview form and its force. How might the interview create spaces for unexpected turns in conversation and encounter? What roles might a conversation between two people play in movements of solidarity and mobilization? And how might filmmakers, cultural workers, and scholars account for its potential? These questions call for a closer inquiry into how preset scripts and framings, which often circumscribe the method of the interview, foreclose the “view in between” that Hamzah evokes; or, as Chikhani remarks, how exhibiting such works in cinemas or art galleries might underscore both the urgency of widening the reach of political images and the paradox of their stubborn insularity. Responding to these questions reveals what Sarlin describes as the “partiality of the interview form,” a manner of refusing conceptual closure, highlighting what is singular rather than total, while simultaneously recognizing partisan inclinations, in the political sense of the term. Keeping open the conversation, Bechara’s call to talk about it insists on the labor of resistance, unfolding across our archives, screens, and communal gatherings.

****

Acknowledgments: The idea of this publication draws on extensive conversations with Razan AlSalah, held during the organization of the workshop Forms of resistance/ Love is the deepest and following its subsequent screening program. The workshop, screening program, and this publication have been made possible thanks to the support of PERICULUM Fondation pour l’art contemporain and Concordia University’s Feminist Media Studio.

Title video: untitled part 1: everything and nothing (1999–2001)

{1} Jayce Salloum, “Sans titre/untitled: Video Installation as an Active Archive,” in Projecting Migration: Transcultural Documentary Practice, ed. Alan Grossman and Áine O’Brien (Wallflower, 2007), 169.

{2} Diane di Prima, “Revolutionary Letter #8,” in Revolutionary Letters, 5th ed. (Last Gasp of San Francisco, 2005), 17.