Striking Evidence \

A Counterforensics of Courtroom Assemblies

Kelli Moore

Dedicated to Christina Spiesel

****

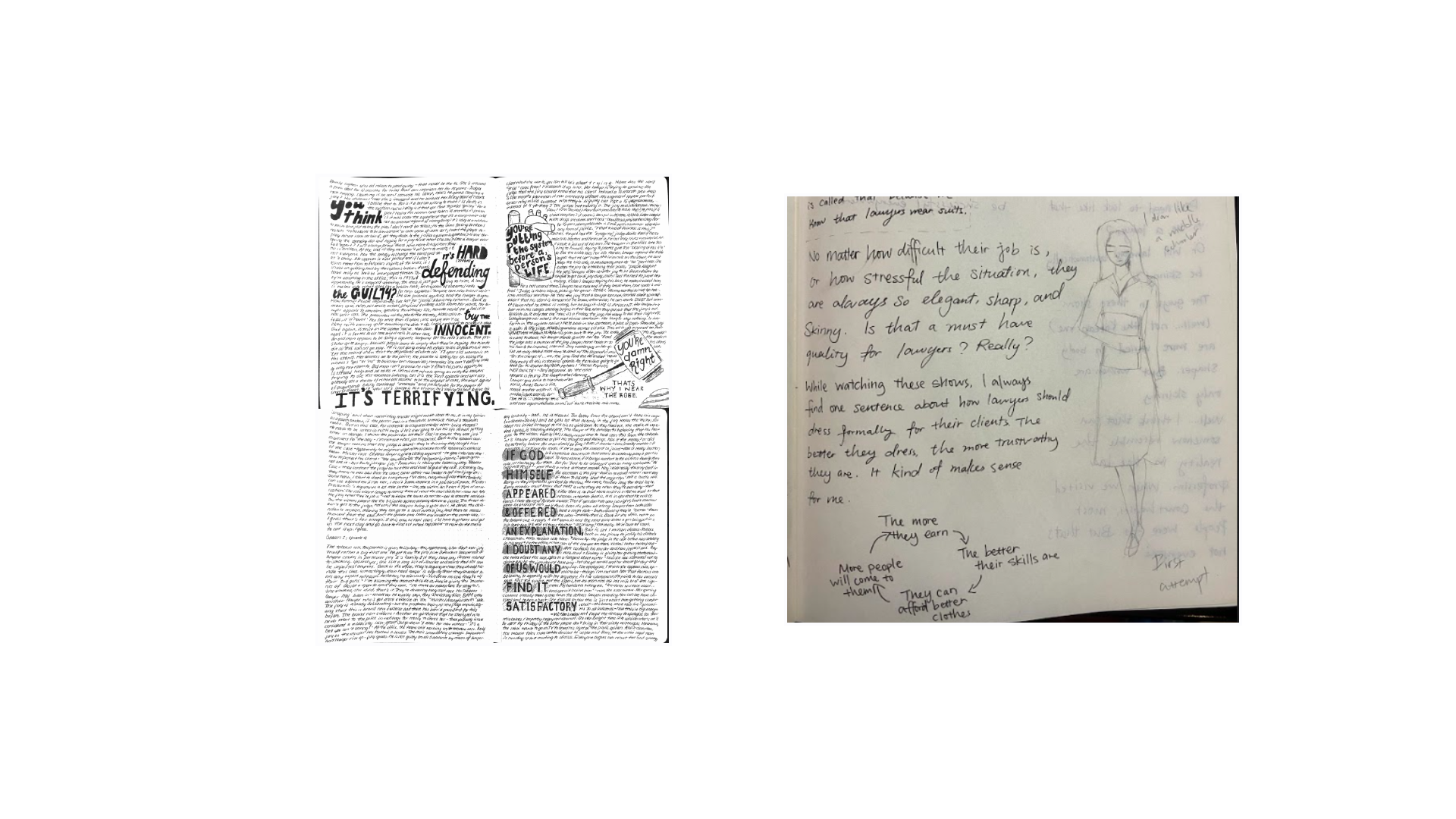

Led by the question “How does the audience see the world?” this essay describes courtwatching as a form of counterforensics. Below I examine media made through participant observation by two different courtroom audiences: the community organization Court Watch NYC, and a group of New York University students engaged in a courtwatching practicum course. In the two examples developed here, the drawing, writing, and marking of these courtwatchers reveal renewed and resistant courtroom assemblies that shift the ancient, medieval, and early modern iconography of the figure of Justice and lawyers in Anglo-American criminal courts. I refer to these marking practices collectively as scrivening or Common Paper in order to position media from the courtroom audience as a counterforensic record obscured from the vision of Anglo-American jurisprudence. These are abolitionist practices that are quietly adversarial toward the criminal system’s data collection. They are not loud; they do not pursue “action” aggressively as in some activist modes. Instead, they challenge “knowledge production in the carceral space through orderly presence rather than vocal outbursts.”{1} The scrivening practices highlight a counterforensic strategy where court-case notations are made concurrently with the live courtroom record but express quite different interests and concerns from those in the roles of prosecutor, judge, court, and police officers. The notational practices examined here are counterforensic because they produce a courtroom record that critically reflects upon the criminal system as a corrupt system rather than as typical individual case data that appears objective or neutral. Courtroom scrivening enlivens the abolitionist principles of refusing to see and hear courtroom activity as neutral and being in solidarity with accused people. I read the scrivening of these courtwatchers in two ways: through the weight and buildup of ink and graphite on paper in the students’ drawings of courtroom activity, and through the tick marks and writing added to case disposition forms by Court Watch NYC participants, which are eventually published online. Together, both forms of counterforensic scrivening belong to what Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel call “object-oriented democracy,” invigorating how public assemblies bear witness to law’s performance in the contemporary “posttrial” era.{2}

Court Watch NYC courtroom sketch. Taken from Court Watch NYC’s 2020 report “Eyes on 2020: New York Bail Reform Accountability and Implementation.”

Court Watch NYC courtroom sketch. Taken from Court Watch NYC’s 2020 report “Eyes on 2020: New York Bail Reform Accountability and Implementation.”

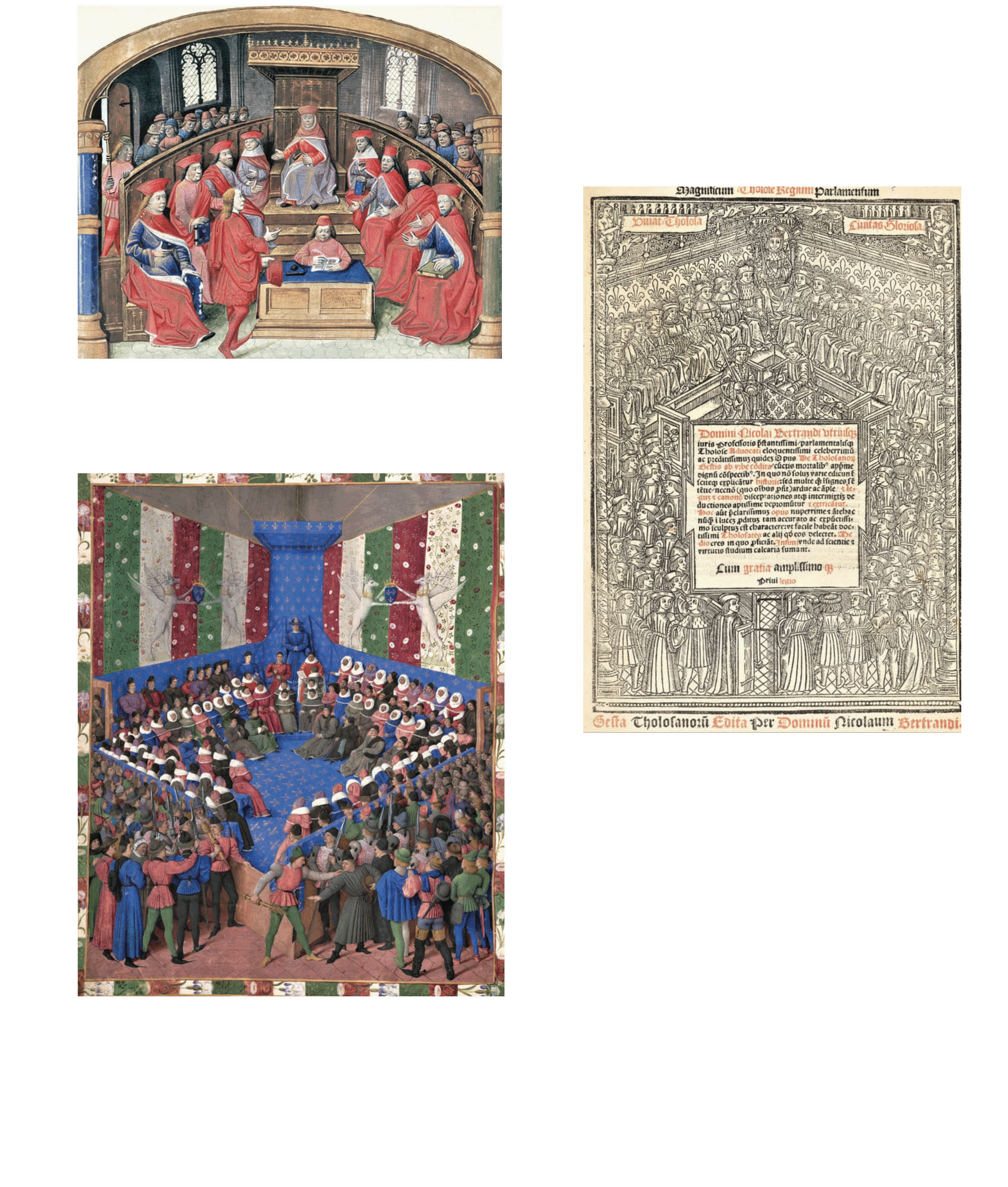

The transformation of the courtroom audience is not simply a matter of the gradual rise and eventual disciplining of the “mob,” “punishment crowd,” “spectators,” and “viewing public,” as they are variously known. In the eighteenth century, the US courtroom audience was transformed via the First and Sixth Amendments into a legally protected assembly, whose duty to bear witness to the trials of their peers made possible a general right to confront one’s accusers. The descendant of the ancient, medieval, and early modern court crowd is the twentieth- and twenty-first-century courtroom audience. Contemporary scholarship on this audience reveals their gradual welcome to, then cordoning off and gradual disappearance from, courtrooms.{3} In the spectacular trials across early modern Western Europe, the unruliness of crowds added moods to law’s mise-en-scène that were both pious and mocking, merciful and retributive. These moods and the varied architectural settings in which they were experienced changed over time.

My analysis of courtroom audience scrivening is indebted to several scholars of Anglo-American law’s visual and theatrical cultures. In Representing Justice, Judith Resnik and Dennis Curtis focus on blind Lady Justice iconography in law and the coevolution of public spaces of legal activity.{4} The representation of Justice is part of a long line of teaching and learning tools covering all aspects of legal practice; such figures get us thinking about abstract law as moral idea(l). Expanding beyond the figure of Justice, Peter Goodrich’s concept of obiter depicta gathers the overlooked visual and physical forms that fade into the background of legal activity: architecture, costumes, emblems, guidebooks, murals, paintings.{5} His astute reading of normative themes of law as they appear in iconic symbols is motivated by the question “How do lawyers see the world?” I locate this question elsewhere: How does the courtroom audience see the world? Legally themed artwork is a picture of the nature of governance—the governing principles and covenants between God, a mediating king or sovereign (government), and a people who consent to be ruled (until they don’t). Turning attention to the audience’s vision is a way of taking up the covenantal tradition in liberalism, which debated the people’s obligation to resist corrupt kings. If legal emblems show us an ideal vision of governance, what might the markings of courtroom audiences reveal?

To focus on courtroom audiences is necessarily to be concerned with their performance in legal settings. A valuable history by Julie Stone Peters examines criminal trials as performance spectacle, demonstrating how witnessing crowds have been represented over the centuries.{6} In engravings, paintings, sketches, diaries, novels, and guidebooks, crowds are depicted as gesticulating, passionate spectators whose responses could range from spellbound thrall to a boredom tinged with viciousness. But it is the lawyer crowd, its creation of professionalization media including staged moots at Inns of Court to practice being and looking like a lawyer, that draws the most attention in Peters’s text. Lawyers hone their persuasive qualities through acts of theatrical performance, raising the question not simply of whether law ought to engage in theater, but how much it ought to: nihil ex scenâ or multum ex scenâ—should law take “nothing from the theater” or “much from the theater”?{7} It remains unclear which side of this debate has won out historically. What is clear is that by the nineteenth century, the traditional spectators of law—often depicted as a chorus that observed, hoped, and at times turned hostile through the persuasive alchemy of lawyers and judicial illocutions—have mostly disappeared from the court setting in Anglo-American contexts.

Witnessing crowds have changed since the ancient, medieval, and early modern representations Peters describes. Scholars provide clues to the journey of the crowd into and out of today’s criminal courtroom and its effect on ways of knowing law. First, scholars point out that crowds have taken to the sofa for fictionalized entertainment, performing their spectator role in front of televised police procedurals and other forms of justice-oriented melodrama.{8} This has consequences in courtrooms; for example, the glorification of forensic science in crime-scene investigation television has influenced the jurying of real-life court cases—the so-called “CSI effect.”{9} For their part, judges now play and work across genre, finding successful careers judging and consulting on reality TV shows, which has implications for ancient concerns about “how much theater” to allow into law. Second, official courtroom architecture is increasingly hostile to audiences. Linda Mulcahy suggests that the modern courtroom encroaches upon the audience by both cordoning off space and wiring electronic networks for remote viewing.{10} Where in the past unruly crowds could resist law’s performance, today’s courtroom design increasingly resists crowds.

From the functioning courtroom perspective, critical legal scholars describe a “posttrial world” caused not by television or internet viewership, but by increased pretrial plea agreements where prosecutors ensnare the accused in communication around pleading to lesser charges. Prosecutors rule the criminal court because they prey upon those who cannot afford to risk standing trial, despite the fact there is no constitutional foundation for plea bargaining.{11} All of this leads to a posttrial world and the empty courtroom where assembly is limited. Under these conditions, how can we account for the contemporary status of the courtroom audience and the theater of court activity? How can we reflect on acts of bearing witness commanded by the Constitution? What are some expressions of evidence that run counter to courtroom forensics? From what media does such evidence descend? These questions point toward an abolitionist methodology of the courtroom audience as a repressed and oppressed assembly, one that must acknowledge black feminist contribution to forms of accountability—what and how we can know about the official archive of slavery from the perspective of those who suffer it most—such as Simone Browne’s description of sousveillance, Kara Keeling’s reading of the “unaccountable Bartleby,” and Saidiya Hartman’s “critical fabulation” method, which asks how the enslaved might speak through the archive.{12}

Court Watch NYC courtroom sketch. Taken from Court Watch NYC’s 2020 report “Eyes on 2020: New York Bail Reform Accountability and Implementation.”

Court Watch NYC courtroom sketch. Taken from Court Watch NYC’s 2020 report “Eyes on 2020: New York Bail Reform Accountability and Implementation.”

A counterforensics of the courtroom audience is emerging in new forms of spectatorship and witnessing. Firsthand accounts of literate spectators of Inns of Court of the early modern period have achieved contemporary, though small, political formation. Theorizing court audience media draws on the public assembly as a form of life.{13} As Anne Davidian and Laurent Jeanpierre put it, “There is already an interpenetration, a dialogue, an entire historical dialectic between instituted assemblies and instituting assemblies, between assemblies ‘from above’ and assemblies ‘from below.’” Assemblies are more than a “resurgent civic body”; they are also “the locus of a theoretical and practical battle seeking to alter its political function.”{14} Movements like community bail funds, jury-nullification work, copwatchers, and courtwatchers are reflections of what assemblies are doing in criminal law. I have previously written about university student court audience drawing as a form of free association that produces counterforensic knowledge on the criminal courts.{15}

Assemblies may be experienced as performances or experiments, as Davidian and Jeanpierre suggest. Critical engagements with courtroom audiences commission, coproduce, and study their media-making with a critical eye toward popular evidence. Housed at the Chicago History Museum are Franklin McMahon’s surreptitiously created images of the 1955 Emmett Till trial.{16} It is not hyperbole to suggest that his sketch of Till’s uncle identifying his nephew’s murderers from the witness stand is one of the most important drawings in the history of Anglo-American law. Michelle Castañeda’s Disappearing Rooms: The Hidden Theaters of Immigration Law captures an experimental documentary turn in today’s highly specialized legal spaces and spectacles (or conspicuous lack thereof).{17} Working with Molly Crabapple, a professional illustrator, Castañeda describes closed immigration court hearings, giving us access through an illustrated critical legal theory hybrid text. Chroniques de l’injustice ordinaire, written and illustrated by visual artist Ana Pich, discloses antiforeigner and bourgeois bias in Francophone civil law practice, in comic book form.{18} Graphic Justice is an edited collection that connects the rational progression of comic book storyboarding to principles of legal theory. Editor Thomas Gidden observes how a comic’s complex form can itself “provide avenues for conceptualizing and engaging with issues in legal theory.”{19} Jane Rosenberg’s comic Drawn Testimony explores a host of law topics that cross the vocational biography of the paid courtroom illustrator with the lives of defendants she has drawn over the years.{20} Depictions of the courtroom audience are not always by paid professional sketch artists. In The Courtroom Audience Residency Report, artist Mark Fischer experiments with curating the markings of individual courtwatchers with and without formal art training.{21} Fischer invites creative workers to observe courtroom activity with him for six hours; afterward he and the invitees share a meal and discuss the encounter. Unique to this project is that courtwatchers are compensated for their time and a written and drawn record is archived in reports exhibited by Fischer’s organization, Public Collectors.

It is crucial that all of these experimental texts on court audience visual culture are produced under the constraint of the well-known interdiction of courtroom photography. Reduced to arcane or analog technologies, these experiments with representing law help distinguish drawing from writing. Goodrich reminds us that even the written word is made available through visual culture: “Images have their own order and concatenation”; thus, while accompanied by words, images are not reducible to them.{22} This is the context in which courtroom scrivening invites forensic analysis. Michael Ralph identifies the development of forensics as the science of capitalist accounting necessary to regulate the economics of the slave trade, writing, “If capital can be defined as privileged access to an asset, forensics is a method that ostensibly secular people and polities use to determine how that privilege is produced, inscribed, regimented, and adjudicated,” such that “every theory of forensics is a theory of capital.”{23} The following analysis of courtroom audience scrivening thus works toward a counterforensics of capital, a forensics of the oppressed. Courtroom audience scrivening offers a counterforensic record of the work criminal courts do to model the subjects of liberal governance.

****

Shared Forensic Histories

Courtwatching is not a traditional occupation with attendant hiring rules and elaborated customs; nevertheless, its media-making is an enduring cultural-historical activity. I suggest these scrivened materials have an enigmatic positioning within the history of Common Paper and commonplace books. In 1895 Edwin Freshfield described Common Paper as a “folio volume of 298 pages, on paper, in a limp brown leather cover.”{24} The book contains a register of the members of the Scriveners’ Company of London, formerly the Writers of the Court Letter, and the authoritative orders they produced from 1390 to 1628. The purpose of the folio was, as Freshfield continued, “to draw up, in the shape of a book, a document containing the whole of the ordinances forming the constitution of the Company, which each member as he was admitted might swear that he would obey, and subscribe his name to his oath.” This essay treats Common Paper as a media object that refers not only to legal documents but to the collective acts of writing and notarial recording practices through which legal authority is produced and whose antecedents are found in the courtwatching media I discuss.

Legal writing, the movement and power of law’s concepts, is partially rooted in the Common Paper of scriveners, but also in commonplace books. Common Paper refers to the collection of “legal documents as opposed to literary texts” in books or registers and their intricately organized regulation over time by notaries and guilds.{25} Commonplace books, on the other hand, are generally “notebooks, miscellanies, and other types of manuscript compilation.” Aspects of their preparation and use have ranged from “rigid scholastic methods” to “disorganized memoirs, random observations, or miscellaneous anthologies” that could be bound by expensive or modest materials and printed in varying sizes, frequently with “introductions, tables for indexes, and blank pages with ruled margins.”{26}

From antiquity to the Middle Ages, the technocultural history of scriveners has been organized by quasi-religious fraternities that have spun themselves into professionalized guilds and livery companies as well as a variety of notarial and accounting professions that exist today.{27} Like the writing technologies they employ, scriveners are shaped by the forces of capital. Today, the scrivener’s role has transferred to many government-regulated professions: It is practiced by bookkeepers, CPAs, copyists, public servants, notary publics, software engineers—as well as courtwatchers. Positioned between the histories of Common Paper and commonplace books, courtroom audience drawings and markings constitute an enigmatic form of paper knowledge that stands in the footsteps of both Anglo-American legal writing and the free play of written and drawn observation.

Both Common Paper and commonplace books are generative of forensic methods. Historians of legal writing establish distinct notarial signatures and derive levels of concern for topics by analyzing, for example, the length of the writing; whether signatories were under duress, based on handwriting analysis; and whether evidence was added to or removed from legal documents. These methods align with the making of imperial archives and the royal memory they support. Torin Monahan suggests that the opposite of royal memory, that of “public memory and archives,” was “grounded from its inception in practices of surveillance and social order.”{28} He offers the example of the public library that, over time, shifted from a place of public sharing of educational resources to a place of data collection and individual responsibilization in the form of checking out books, paying late fees, and policing the silence and decorum of others. Yet, while the public archive is the political expression of liberal governance and subject-making, courtroom audience media complicate Monahan’s conclusion—that “counter-surveillance efforts embrace archival reason and appeal to the law”—by modeling a more radical form of public evidence.{29}

Counterforensic methods also surface in the organization Court Watch NYC, which develops its own Common Paper, improving its data collection by merging qualitative and quantitative observation forms, gathering feedback from volunteers, designing additional post-court reflection forms, and reminding volunteers to use the most updated forms.{30} Gradually, this work on Common Paper manifests in reports that publicly denounce Criminal Record Information and Management System (CRIMS) data and prosecutors’ “progressive prosecution” lies. Court Watch NYC’s counterforensic methods allow volunteers to speak collectively and engage in real struggles with abolitionist principles. The organization is joined in these struggles by such practices as student courtroom drawings, which create a record of audience legal consciousness that can be revelatory of the people’s will to free associate, in the double meaning of that psychoanalytic and community-organizing term. New to the courtroom scene, abolitionists engaged in courtwatch media-making remind us that the forms of witnessing and expression granted by the Constitution remain undisclosed and undertheorized.

****

Student Courtwatch Drawings

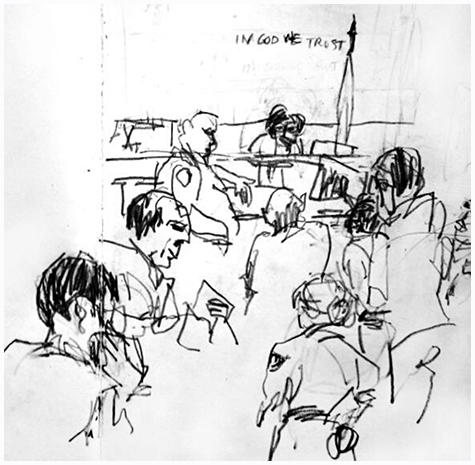

Figure 1

This drawing is from a student courtwatcher at a local university; it is part of a collection of student courtroom audience drawings over which I am guardian. Consider the weight and buildup of black ink in this rendering of a family court judge, Honorable Judge Hasa A. Kingo, who is a dark-skinned man. At the time of the drawing COVID protocols were in effect. A displacement occurs in the drawing between black COVID face mask, black skin color, and black projection technology—a varied semiotics of blackness. The weight and buildup of ink on the base of the stand match that of the police officer’s uniform below. One imagines, if they were visible, that the judge’s black robes, the traditional judicial livery of Anglo-American law, would be subject to the same weight and buildup. Judge Kingo’s face is rendered without color, shading, or the buildup of ink; only his head is outlined. While the political category of dark skin is unarticulated in the drawing, the courtroom technology and face mask acquire presence through hand strokes made of black ink. A contemporary variation on blind Lady Justice iconography, Hon. Judge Kingo is rendered as a machine-man—his head both a screen and onscreen, the rest of his body a communication technology used during and after COVID to conduct court business remotely.

The OED gives displacement two meanings: “the act of moving something from its place or position” and “the occupation by a submerged body or part of a body of a volume which would otherwise be occupied by a fluid.” Drawings create and contain problems to be solved, often through displacement. This drawing (figure 1) stages displacement as the work of liberalism’s color-blind racial fantasy. Hasa Kingo is one who is called “Black.” The drawing displaces this naming, emphasizing Kingo as one who is called “Judge.” Anglo-American law employs comparatively few black judges. So what to make of the absence of skin tone from this record? What is done by blackening elements of the court’s mise-en-scène but not the judge? These questions aren’t simply after greater representation and inclusion of black judges in Anglo-American law, though indeed their numbers are low. The drawing’s tonal displacements offer pathways into the enigmatic history of race in liberalism. Forensically it is not possible to ascertain whether Judge Kingo was intentionally unmarked, intentions and liability being sine qua non in law. The drawing opens larger questions about just how and why black and otherwise dispossessed peoples participate in liberal public office as judges, notaries, historians, ethnographers, archivists, and courtwatchers, as these are occupations useful to the state. The drawings are a platform, a demonic ground for counterforensic examination and analysis of liberal assemblies.

As Margaret Davidson writes, “The drawing surface, be it paper or some other substance, has an immediate and irrevocable relationship with the mark, and so is deliberately chosen by the drawing artist. This choice happens at the beginning of any drawing project and is made as the artist plans what the drawing is about and what the drawing is intended to look like.”{31} The absence of a suggestion of Hon. Judge Kingo’s blackness is an (un)conscious deed, a doing that is displaced onto the black face mask, projection technology, and officer’s uniform through weight and buildup. Courtroom audiences use the buildup and weight of ink and graphite to solve the problem of capturing liberal infrastructures, often unconsciously. This detail unifies many court audience drawings in the collection (see figures 2 and 3 below). Elsewhere, ink and graphite seem unable to surface the blackened subjects of liberalism, only its judicial architecture: the judge’s bench, judicial robes, police uniforms, jury seats, the In God We Trust motto, the American flag.

To grasp the full weight of this collection of courtroom drawings is to understand that it and other markings generated by the courtroom audience have no legal status. A commonsense view of audience communication might (mis)recognize its generated media as part of the official recordings of courtroom illustrators and stenographers. However, this is not the case. There are no official documents, no official archive of the (un)conscious or speech acts of the courtroom audience in over two centuries of US jurisprudence. Jocelyn Simonson’s attention to the importance of the courtroom audience has invigorated a recent surge of civic engagements with the interlocking First and Sixth Amendments to the US Constitution, which charge the public with assembling to bear witness to the trials of their peers, not as jurors but as audience members.{32} They interlock in the courtroom because the people have the right to publicly assemble (First) and to face their accusers in a court of their peers (Sixth). The interlocking amendments make witnessing a duty, obligation, and right. However, while the amendments remain in place as demands for recording, there is silence about the status of the forensics of courtroom witnessing.

****

Court Watch NYC

Another type of marking from the courtroom audience is practiced by the community organization Court Watch NYC. Founded in 2018, Court Watch NYC puts volunteers to work in acts of list-making, marking, and tab-opening, contemporary iterations of the scrivener and clerk roles whose nineteenth-century apex Cornelia Vismann details in relation to lawmaking and courts.{33} Court Watch NYC volunteers receive hours-long training sessions on how to observe criminal courts. In the sessions, led by attorneys affiliated with the group, a mock criminal court hearing is staged while participants fill out a case disposition form based on what they observe. I attended several sessions and was struck by the difficulty of the work. Court Watch NYC simulates criminal courtroom procedures in unused law school classrooms over weekends, a testament to institutional relationships between the criminal system and the university.

The classroom setting of Court Watch NYC training reveals the targeting of legal infrastructure as the group’s site of intervention. Trainings frequently occur in law school classrooms because these rooms are outfitted with architecture resembling the judge’s bench, the witness stand, and the prosecution and defense speaking positions of modern courtrooms. Law school classrooms replicate the courtroom infrastructures for lawyers in training. Recalling early modern moots, the law school classroom adds further ambience to the forms of paperwork handled by Court Watch participants.

The Court Watch form is designed after the Criminal Record Information and Management System (CRIMS). CRIMS is an automated case-management computer ledger capturing data at all stages of a criminal court case, from arraignment to disposition to appeal when applicable.{34} The system receives daily arrest data, which is stored to update and maintain case records—criminal histories—of defendants. The routines of criminal courthouses—issuing sentences, setting bail, and the recordkeeping associated with these tasks—cannot occur without a steady stream of CRIMS data.

CRIMS data is integral to Court Watch NYC training sessions. Volunteers create a set of documents that mediate their apprehension of illocutionary courtroom speech. Court Watch NYC trains volunteers on how to grasp case dispositions in the criminal courtroom and record them onto a list (figure 4 below). They practice marking their lists while listening to an abbreviated mock trial delivered in a law school classroom. The training develops listening skills and demystifies the variety of abbreviations and numerical codes germane to the case dispositions—the very data recorded in a genuine CRIMS data row. The training process is mentally taxing because the work concerns parsing disposition codes as they are spoken live by the mock trial members and quickly marking the correct box. Time is of the essence in these listening and marking practices, and volunteers train for accuracy and speed.

In the context of the misdemeanor courts, Court Watch NYC volunteers are rewriting the scrivener’s traditional role, linked as it is to the history of enslavement. In doing so, they invent and begin to establish (un)professional standards of the courtroom audience and their nascent records. Misdemeanor courts have come under increased scrutiny for the ways they expand court powers to monitor both accused persons and plaintiff roles in the criminal court process, using an extensive caseload of nonfelonious and victimless crimes.{35} Individuals in the misdemeanor system are marked through lengthy monitoring regimes and courtroom hearings in ways that expose recidivists to jail time. The misdemeanor context is also a “posttrial” one, in which accused persons are routed into taking pleas rather than risk standing trial before a jury of their peers. Further troubling is the fact that criminal court ledgers are increasingly found to possess inaccurate records, leading to compromised rights of citizenship for former accused persons. Cases that contest the accuracy of CRIMS data across several states throw the knowledge generated from that data into crisis. In this context, the courtwatch volunteer is a new scrivener who beckons to the courts at this “posttrial” moment when courtroom audiences are disappearing. In this gradual organization of the courtroom audience into a community of courtwatchers, a new set of public records is coming into existence. By documenting and creating records of case dispositions, Court Watch NYC volunteers appear to work at “seeing like the state,” but the court data they make legible is meant to hold accountable district attorneys who were elected on “progressive prosecution” promises.{36} The so-called “progressive prosecutor movement” responds to the systemic social inequities of mass incarceration through methods such as nonenforcement, diversion, decarceration, police accountability, and the reform of legal administrative processes. Progressive prosecutors encompass “people in an elected prosecutor position who campaigned using a reform-based agenda.”{37}

Court Watch NYC volunteers contest not only legal writing but legal data. The work of these audience volunteers contributes to hidden histories of public accounting.{38} Deepening what the term public accounting can mean, volunteer scrivening provides an accountability check against the promises made by New York State “progressive” district attorneys by recording in analog form case dispositions, which are then published to reflect critically on the CRIMS ledger. The counterforensics of Court Watch volunteers also strengthens ties with Legal Aid, who report back to the organization which judges are most carceral and set the most bail. This form of counterforensic seeing identifies the city’s most violent judges and campaigns for their potential removal from the bench.

In contrast to the student’s drawing of Hon. Judge Kingo, who is depicted as “just trying to think the best way to do it” for the living arrangements of “Mom & Son,” Court Watch NYC’s case information sheets (figure 5) flag judges who set high bail on the accused—for example, “bail set at $10,000 for a person of limited financial means”—and thus increase the likelihood of pretrial incarceration. The volunteers’ scrivening is later transformed into digital communication with observations posted to Court Watch NYC’s Instagram account alongside advertisements for upcoming courtwatching shifts. These examples of Common Paper—the student drawings and the case information sheets alike—evince counterforensics of the courtroom audience and some failures of judicial intervention in governance. Both contribute to the iconography of Justice. They make visible particular cases and actions by particular judges; justice situated within electronic communication networks; ambivalent references to blackness in judicial iconography. Contemporary court crowds have transformed the means of legal knowledge production. They have moved beyond the passions to targeted analysis of judicial flaws.

The significance of these drawings and marked documents is that, although peers are called by law to assemble in the courtroom, the forensics they create from the audience seat is unofficial, unprofessional, individual, idiosyncratic, and unhoused. The materials produced by Court Watch NYC and student courtwatchers are grounded in the assembly—they are public. Serious questions arise, then, about the nature and function of these records: What is the legal standing of these documents? How do they work toward abolition? What history of paper knowledge do they stem from and produce? Should they be archived, and if so, by whom, at what location?

****

In protecting the audience’s ability to listen, “the presence of the local audience assures the defendant and the community that the government will be kept in check.”{39} Courtwatching enacts the separation of courtroom powers that marks liberalism. Student and volunteer courtwatchers create media that are betwixt and between traditional forensic strategies and counterforensic tactics. Increasingly, counterforensics is implicated in leaving key concepts and infrastructures of oppression unchanged.{40} This is also true for student and volunteer courtwatchers and their scrivening. Yet I hesitate to destabilize the potential for counterforensic forms of evidence. Counterforensics experiments with and promotes abolitionist principles that, crucially, rest upon the process of struggles that are collective and personal.

Without office, station, livery, or Common Paper, the court audience has no officially recognized recording. Their marks are one of the few emergent sets of counterforensic records produced for and by the people. The courtroom assembly proposes to offer counterforensic analysis of courtroom architecture through their witnessing. Their scrivening and markings become a record that forces us to ask who the assembly is and what counterforensic ways of seeing and recording it’s capable of. These markings are how the assembly accounts for itself and takes stock of liberalism’s separation of powers within the courtroom.

Court Watch NYC’s reports and students’ court drawings constitute a kind of popular evidence that raises questions about common archival practices and their accompanying forensics. When Court Watch NYC members make tick marks, they challenge neoliberal “progressive prosecution” rhetoric, checking it against the criminal system’s ledger. Likewise, when student courtwatchers build up ink and graphite in their drawings, they point toward infrastructures of law as a repressed sight/site of ideology. Together, both forms of assembly establish Common Paper among different courtroom audiences. Their Common Paper suggests that counterforensic tick marks and drawings are not simply data but a form of status that may one day succeed in populist efforts to legally stand otherwise. Rather than asking “How much theater in law?” the counterforensics of courtwatching asks, Whose evidence in law, how is it established, and to what effect?

{1} Jocelyn Simonson, Radical Acts of Justice: How Ordinary People Are Dismantling Mass Incarceration (New Press, 2023), 13.

{2} Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, eds., Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy (MIT Press, 2005).

{3} See Linda Mulcahy, “Architects of Justice: The Politics of Courtroom Design,” Social and Legal Studies 16, no. 3 (2007): 383–403; Jocelyn Simonson, “The Criminal Court Audience in a Post-Trial World,” Harvard Law Review 127, no. 8 (June 2014): 2173–232; Kelli Moore, “Judgment’s Tableaux: The Court Made Public,” Parapraxis (2023): 225–31.

{4} Judith Resnik and Dennis Curtis, Representing Justice: Invention, Controversy and Rights in City-States and Democratic Courtrooms (Yale University Press, 2011).

{5} Peter Goodrich, Legal Emblems: Obiter depicta as the Vision of Governance (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

{6} Julie Stone Peters, Law as Performance: Theatricality, Spectatorship, and the Making of Law in Ancient, Medieval, and Early Modern Europe (Oxford University Press, 2022).

{7} Peters, Law as Performance, 298.

{8} Neil Feigenson and Christina Spiesel, Law on Display: The Digital Transformation of Legal Persuasion and Judgment (NYU Press, 2009).

{9} Michele Byers and Val Marie Johnson, eds., The CSI Effect: Television, Crime and Governance (Lexington Books, 2009).

{10} Mulcahy, “Architects of Justice.”

{11} See Jed S. Rakoff, “Why Prosecutors Rule the Criminal Justice System—and What Can Be Done About It,” Northwestern University Law Review 111, no. 6 (2017): 1429–36.

{12} Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Duke University Press, 2015); Kara Keeling, Queer Times, Black Futures (NYU Press, 2019); Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (June 2008): 1–14.

{13} I am gesturing here to Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, trans. Joseph Ward Swain (George Allen & Unwin, 1915).

{14} Anne Davidian and Laurent Jeanpierre, introduction to What Makes an Assembly?: Stories, Experiments, Inquiries, ed. Anne Davidian and Laurent Jeanpierre (Sternberg, 2023), 13.

{15} Moore, “Judgment’s Tableaux.”

{16} See the Chicago History Museum exhibition Injustice: The Trial for the Murder of Emmett Till, accessed March 2025.

{17} Michelle Castañeda, Disappearing Rooms: The Hidden Theaters of Immigration Law (Duke University Press, 2023).

{18} Ana Pich, Chroniques de l’injustice ordinaire (Massot Éditions, 2023).

{19} Thomas Gidden, ed., Graphic Justice: Intersections of Comics and Law (Routledge, 2015), 2.

{20} Jane Rosenberg, Drawn Testimony: My Four Decades as a Courtroom Sketch Artist (Harper Collins, 2024).

{21} Mark Fischer, The Courtroom Audience Residency Report (Half Letter, 2019).

{22} Goodrich, Legal Emblems, 11.

{23} Michael Ralph, “Forensics,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 87, no. 3 (September 2019): 651.

{24} Edwin Freshfield, “Some Notarial Marks in the ‘Common Paper’ of the Scriveners’ Company,” Archaeologia 54, no. 2 (1895): 239.

{25} Peter Beal, A Dictionary of English Manuscript Terminology 1450–2000 (Oxford University Press, 2008), 368.

{26} Beal, English Manuscript Terminology, 83.

{27} Part of scrivener history is that it passes through the enslaved person. Some enslaved people were put to work as scribes, often of legal documents testifying to their identity, witnessing and writing law from the hand of one who was not free.

{28} Torin Monahan, “Visualizing the Surveillance Archive: Critical Art and the Dangers of Transparency,” in Law and the Visible, ed. Austin Sarat et al. (University of Massachusetts Press, 2021), 133.

{29} Monahan, “Surveillance Archive,” 133.

{30} Court Watch NYC, email communications with author, 2018–20.

{31} Margaret Davidson, Contemporary Drawing: Key Concepts and Techniques (Watson-Guptill, 2011), 32.

{32} See Simonson, Radical Acts of Justice; Simonson, “Criminal Court Audience.”

{33} See Cornelia Vismann, Files: Law and Media Technology, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young (Stanford University Press, 2008).

{34} C.R.I.M.S. Manual: Court Computer Program for Warrant Verifications (US Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, 1992), accessed April 3, 2024.

{35} See Kelli Moore, Legal Spectatorship: Slavery and the Visual Culture of Domestic Violence (Duke University Press, 2022); Issa Kohler-Hausmann, Misdemeanorland: Criminal Courts and Social Control in an Age of Broken Windows Policing (Princeton University Press, 2018); Jenny Roberts, “Crashing the Misdemeanor System,” Washington and Lee Law Review 70, no. 2 (Spring 2013): 1089–131.

{36} I refer here to James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (Yale University Press, 1998).

{37} When You’re a Hammer, Everything’s a Nail: Examining the “Progressive Prosecutor” Movement and Possibilities for Future Reform (Chicago Appleseed Center for Fair Courts & Chicago Council of Lawyers, 2024), 1.

{38} See Theresa Hammond and Denise W. Streeter, “Overcoming Barriers: Early African-American Certified Public Accountants,” Accounting, Organizations and Society 19, no. 3 (April 1994): 271–88; Cheryl R. Lehman, “‘Herstory’ in Accounting: The First Eighty Years,” Accounting, Organizations and Society 17, nos. 3–4 (April–May 1992): 261–85.

{39} Simonson, “Criminal Court Audience,” 2198.

{40} See Simonson, Radical Acts of Justice; Monahan, “Surveillance Archive.” Simonson in particular points to the critical diversity in different waves of courtwatch groups. Groups engage court officials to varying degrees; they also disagree among themselves about how and to whom to direct their demands.