We live in a world filled with images that are captured, edited, and published at hyper speeds. Images referring to images. Our political, ethical, and intimate lives are constructed around images, through images, and in images.{1}

The Abounaddara Film Collective, an anonymous group of Syrian filmmakers that emerged alongside the onset of the country’s civil uprising in 2011, drafted these lines as the preface to their brief 2014 “concept paper for the coming revolution.” In the paper, they claim a “right to the dignified image,” a transnational civil protection that the collective wishes to see amended to the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Maintaining that such a protection is essential to preserve the dignity and integrity of Syrians as images of their abjection circulate the globe with increased frequency, the right to a dignified image has emerged as an integral corollary to the collective’s prodigious video output over the past six years.

Abounaddara insists that it is time to re-evaluate the role and value of atrocity imagery in wartime reporting and humanitarian campaigns. In the intensifying circulation of audio-visual media through the digital networks of global communication, the collective challenges a conventional notion that recording technologies are tools added to contiguous, pre-existing physical spaces. Instead, their frame encourages us to see cameras, the images they produce, and the networks through which they circulate as constitutive parts of virtual geographies, or spaces linked by the vectors of information that transmit images of events across the globe. For the collective, the ongoing war in Syria is an international event in that journalism covering the war produces a feedback loop between the physical sites of conflict and the virtual sites of mediated encounter. Wherever the violence depicted is framed in sectarian and geopolitical terms, media coverage retroactively supports President Bashar al-Assad’s continued rule as the Assad family have long framed their sovereign claim in Syria through their unique ability to manage a diverse population. For the collective, the right not to live under the conditions of a brutal dictatorship is integrally linked to the right to a dignified image.

Over the past three years, I have programmed Abounaddara’s videos and participated in public events with the collective’s spokesperson. This conversation with Abounaddara took place by email in Fall, 2017.

****

Interview

Jason Fox

Four years after Abounaddara emerged alongside the onset of the Syrian Revolution, the collective asserted a claim for a right to a dignified image. What does the claim call for?

Abounaddara

Since 2011, the screens of the world have exhibited Syrian bodies marked by indignity while the citizens of democratic states are protected from being exhibited in such a way.

Faced with this form of segregation, what is to be done? How can a regime of representation that undermines the principle of dignity and the idea of a common world be remedied?

In 2013, we published an article titled “Respectons le droit à l’image pour le peuple syrien” (Respect the Right to the Image for the Syrian People), and in conjunction we circulated a short film denouncing the spectacle of indignity. But since our call fell on deaf ears, in 2014 we proposed a critique of the media, as well as a legal approach with the help of a Syrian lawyer and legal scholar. And since 2016, we have pursued this critical reflection in the framework of a course at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm.

In short, we call for the recognition of every human being’s right to enjoy a dignified image on the basis of existing provisions in international law. This is to reaffirm the principle of dignity in the face of those who abuse the representation of the world’s most vulnerable individuals in the name of freedom, solidarity or compassion.

JF

Did this claim inform Abounaddara’s practice from the earliest days of the collective, or is it a response to particular conditions that emerged later?

A

Abounaddara was born out of a need to liberate ourselves from the dominant images that tend to reduce Syrians to a function of either geopolitics or religion. Our first films released in 2010 show Syrians in their daily lives, neutralizing the geopolitical or religious context that has been plastered all over their faces. There was a claim to dignity to the extent that, in accordance with a precept by a certain Mr. Kant, we represent our own with the consideration that as human beings they must not be treated as means, but rather as ends in themselves.

In 2011, when the popular uprising irrupted onto the streets, we published a statement calling for an aesthetic translation of the call for dignity declared by the peaceful protestors. We launched ourselves into the production of short weekly films aimed at conveying a sensory counter-information while deconstructing the geopolitical or religious frame that distanced Syrians from the common world.

But we realised that this aesthetic struggle could not succeed without questioning the regime of representation in a juridical sense. In addition, we used the platform provided by The Vera List Center for Art and Politics in 2014 to advance our critique of the media and develop a legal proposal.

THE UNKNOWN SOLDIER – PART ONE, Abounaddara (2012).

JF

Following Serge Daney’s argument in the context of the live televisualization of the 1990-91 invasion of Iraq, “We are no longer the witnesses of the world, but rather the witnesses of the images of the world,” the Abounaddara collective seems to suggest that the desire to report live and “from the inside” marks a fundamental transformation in the relationship between war and its media coverage.

A

We discovered Serge Daney’s work thanks to Dork Zabunyan, a film theorist whom our collective has been in dialogue with since 2011. The discovery was also made following a crucial meeting with Osama al-Habaly, an activist who delivered a short anonymous testimony to us about his experiences with the international media a few months after the beginning of the uprising.

Osama—who disappeared into regime detention in 2012—taught us that the images of war ‘from the inside’ broadcast on TV were no longer being filmed spontaneously by activists. These images were rather directly or indirectly produced by the media who conceal their own involvement in order to evade any ethical, legal or political obligations. In other words, we are no longer dealing with a mode of image production based on the figure of the professional journalist, but rather on the local informants called ‘citizen journalists.’

After having produced independent images in the service of the popular uprising, these ‘citizen journalists’ find themselves employed as subcontractors at the mercy of TV channels which demand ever more sensationalist footage in order to satisfy the internal competition between channels, as well as between TV and other media platforms. They find themselves trapped, forced to sanction a pornographic form of representation of war that, in focussing on dead and disfigured bodies, grants spectators the private enjoyment of the pain of others.

In the end, war ‘from the inside’ represents the alignment of the realm of television with the realm of social media, where war can seduce unfettered. This is an historic turning point in which images are produced by the same actors engaged in war and not by professional reporters. More than ever, “images of war are images that wage war,” to quote Serge Daney.

By entrusting war coverage to actors engaged in warfare we undermine the foundations of a truth regime built by generations of journalists and professional reporters. This has become grist to the mill of post-truth, a weapon wielded by all the political and economic powers eager to rid themselves of any counter-power that stands in their way.

MEDIA KILL, Abounaddara (2012).

JF

How does Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s restriction on foreign journalists provide a context, or a cover story, for the conditions of war reportage that you critique?

A

Let’s be precise. The regime has always strictly controlled the entry of journalists to the country. It’s possible to argue that every article or report published by the international media since 1963—the date the Baath Party seized power in a coup—has been produced by journalists who could only report in the country under strict escort by the regime’s secret police. So in 2011, Bashar al-Assad only had to reinforce a rule that had long existed, according to which images of Syrian society had to be produced under state control.

But the media could no longer afford to accept such a rule while the state launched a war against society. There was an obligation to find an alternative in order to dodge any suspicions of complicity when other images were being produced (note, in passing, that there has been a rapid return to the prior situation: foreign journalists are once again queuing up to interview the head of state, despite the fact that in the meantime he has become a suspected war criminal).

It is in this context that TV channels seize hold of the activist images creating a buzz on social media. But in attempting to compete with social media, TV channels have defused the disruptive force of these images while celebrating them together with the entertainment industries.

But the widespread use of activist images has become catastrophic since it hasn’t yielded credible information. It has become a guarantee for the confusion that benefits the Syrian state at the expense of society. But could it have been otherwise in such a dramatic state of war?

In 2014, we published an article in the press as a reminder that alternatives exist, referring in particular to One Minute for Sarajevo, a daily chronicle of the lives of the inhabitants of the besieged city, broadcast daily by a European TV network. We even went so far as to agree to work with a European television network proposing to program our work in its geopolitical slot, contrary to our fiercely anti-geopolitical position. Our challenge was to construct an alternative within the existing framework. As a result, we complied with the codes of the TV documentary format by making a 52-minute-long feature. But we did our best to subvert the format through a disruptive aesthetic that switches between the codes of cinema, video and reportage.

JF

At the heart of the collective’s claim to the right to dignified images is an assertion that photographic representations of war, and especially representations of atrocity, do not remain in the realm of representation. Rather, you seem to argue that they have the capacity to do material, physical harm to Syrians. But this may be a difficult assertion for many people to accept.

A

In mid-March 2011, despite the brutal mobilization of regime forces, a handful of young Syrians take to the streets shouting ‘Dignity’, ‘Freedom’ or ‘The Syrian people will not be humiliated’. Images of these events spread like wildfire via social media. They rapidly mobilize other demonstrators across the country, and reveal the contours of a national community in the process of liberating itself and assembling around democratic values.

Shaken by the images, the regime reacts with the voice of Bashar al-Assad denouncing a conspiratorial ‘war against Syria’. Immediately, state media begins to manufacture images of war, images of masked men firing at the army, corpses of soldiers supposedly murdered by demonstrators described as ‘Zionists from within’. Anonymous videos surface simultaneously on YouTube showing scenes of torture, humiliation or killing, attempting to spread the idea that the country is prey to chaos and barbarism.

So we are dealing with the confrontation of two sorts of image that aim to produce concrete effects on Syrians: on the one hand, images of uprising calling for people to take to the streets to weave new social ties; on the other, images of war seeking to encase them in fear and isolation.

The images of atrocity fall under the latter category: the images of war. And when utilised on a large scale by the Syrian and foreign media, these images reduce society’s struggle to bloody chaos. How can one believe in the revolution if, while demonstrating peacefully, Al Jazeera and CNN exhibit your corpses, and Syrian TV exhibits the corpses of the soldiers you’re supposed to have murdered?

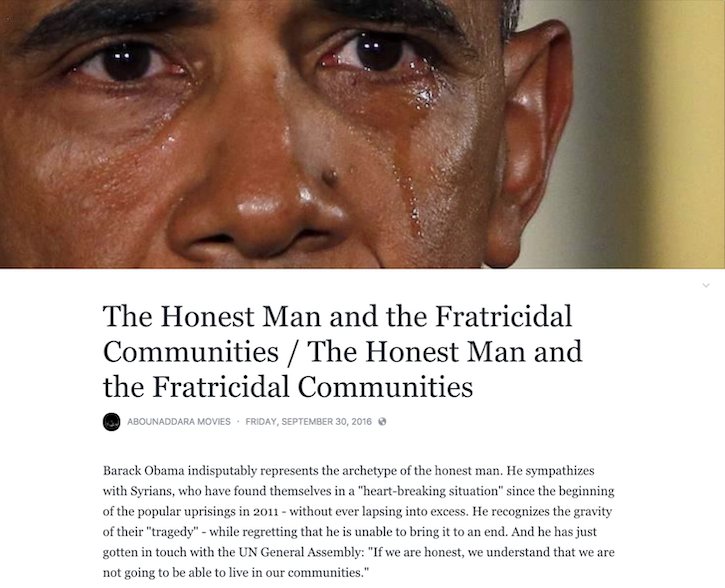

Multiplied by screens, death has invaded the space of our daily lives. It was all the more difficult to resist this daily flow of deathly images because sometimes one was obliged to pore through them in the hope and fear of finding a missing loved one. Syrians ended up traumatized by their own image. As for the distant spectators, they found themselves at best in the same shoes as Barack Obama, to whom we devoted an article entitled The Honest Man and the Fratridicial Communities: in 2011, he admired the ‘transition to democracy in Syria’; in 2016, he could only see ‘religious communities’ killing each other.

“The Honest Man and the Fratricidal Communities,” Abounaddara, 2016

“The Honest Man and the Fratricidal Communities,” Abounaddara, 2016

A more conventional response to negative representations might be to argue that the same technologies of open communication harnessed by corporate media formations in their wartime reporting can also be harnessed by those who wish to offer alternative representations. Cell phones, video hosting platforms, and the internet offer alternative routes to power outside of the corporate media landscape, resources that Abounaddara already employs.

A

This is not a problem of ‘negative representations,’ but rather a regime of representation that flouts the dignity of the weakest and bolsters the dignity of the strongest. What happened in Syria is that cameras were given to people who demanded dignity, while being told: “If you want a place of your own on the screens of the world, if you want recognition, you have no choice but to film your own indignity. For the more stripped of dignity you are, the more the world will look at you and even help you.”

This spectacle of indignity has ended up confining Syrians to the role of the subhuman or, at best, the Elephant Man. Certainly, it is possible to resist by producing dignified images. This is what we’ve been trying to do ourselves for years. But what chance do films like ours have on the screens of the world governed by today’s law of blood (“if it bleeds, it leads”) and market algorithms?

In reality, the law of blood and algorithms only benefits the strongest. Which is actually the case in Syria. The regime itself authorized Facebook and YouTube access after years of blocking access. It did this in February 2011, even though social media was supposedly the Arab Spring’s greatest ally.

JF

Does advocating for the prohibition of certain types of media circulation risk advocating for censorship?

A

It is not a question of prohibiting anything, but rather of applying the same rule to all. Censorship is an argument often deployed by the promoters of the spectacle of indignity. But no one talks about censorship when TVs refrain from showing footage of US victims on 9/11, or when YouTube removes footage of the beheading of James Foley. Even the leader of the French far right, Marine Le Pen, doesn’t dare mention censorship when forced to take down the photos of the beheading from her Twitter account. She’s sooner judged for re-circulating those images, her parliamentary immunity withdrawn because of this attack on human dignity.

Apart from that, the challenge is to defend human dignity without endorsing the notion of the unrepresentable. Saying that something cannot be represented is contrary to the ethic of the filmmaker who must be able to represent anything at all with the tools of art. But death is not just anything. It is a subject that engages humanity’s most fundamental values. Which is why we must represent it ‘in the throes of fear and trembling,’ to use an expression adopted by Jacques Rivette in his essay “On Abjection.” We have already attempted to do this in some of our films, such as the Absence of God or Apocalypse Here. And we will continue to do so as long as it’s necessary.

APOCALYPSE HERE, Abounaddara (2012).

JF

For some, there is legal protection. Can you comment on the ways that many corporate media outlets who are financially invested in Syrian reporting are able to rely on intellectual property laws to prevent others from using their own images, content, and branding however they see fit?

A

No comment.

JF

Why does the collective turn to the United Nations, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as the most meaningful legal and ethical framework to enforce the right to the dignified image?

A

Abounaddara was born in 2010, under a veil of anonymity. We were suspicious of the ‘engaged filmmaker,’ the posture adopted by our elders. We thought it best to develop a filmmaking practice that could inspire people with the minimum discourse necessary.

But it turns out that we are dealing with a regime of representation that drapes itself in the cloak of the universal, invoking freedom while practicing segregation. This is why we have no choice but to oppose it with a higher principle, invoked spontaneously by Syrians themselves, and recognised as such in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, namely: dignity defined as the condition of possibility for the enjoyment of our human rights.

JF

The collective’s interest in the United Nations framework might imply an interest in a universalist framework.

A

We are engaged in a struggle that is part of a universal history—of social struggles led by the anonymous, by pariahs, by outsiders. But the screens of the world enclose us in a single geography: the Middle East of Orientalists, despots and Islamists.

The only universal framework that matters is that of the social struggles we feed on and that we have a duty to feed in turn. It is only in this context that we seek to develop our practice of filmmaking while sharing our work with the citizens of Syria and the world. As for the United Nations, its only interest to us is as custodian of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which grounds our common world on the principle of dignity.

JF

Conventional approaches to human rights video suggest that international communities of humanitarian monitoring, including the UN, rely on broadcast media representations to transmit images of atrocity across the globe in order to “mobilize shame” and compel international actors to intervene.

A

We are image makers. Our job is not to defend a cause, no matter how just, but to use the tools of art to reveal the world in all its states. It turns out that we’ve been driven to defending a cause—the right to a dignified image—because the current regime of representation undermines the possibility for us to accomplish our task as image makers and to enjoy our fundamental rights as humans.

JF

What kinds of engagements have Abounaddara had with the United Nations in support of the collective’s proposed amendment?

A

We have not proposed an amendment. And we hope that more qualified people than us will do so as soon as they finish reading this interview.

THE BATTLE OF ALEPPO, Abounaddara (2016).

Title Video: The Battle of Aleppo (Abounaddara, 2016).

{1} Abounaddara Film Collective, “A Right to the Image for all: A concept paper for a coming revolution,” 2014