Other People’s Words

John Greyson

Karaoke, Stereoscopy, and the (ir)resistable rise of the Shot-for-Shot Remake

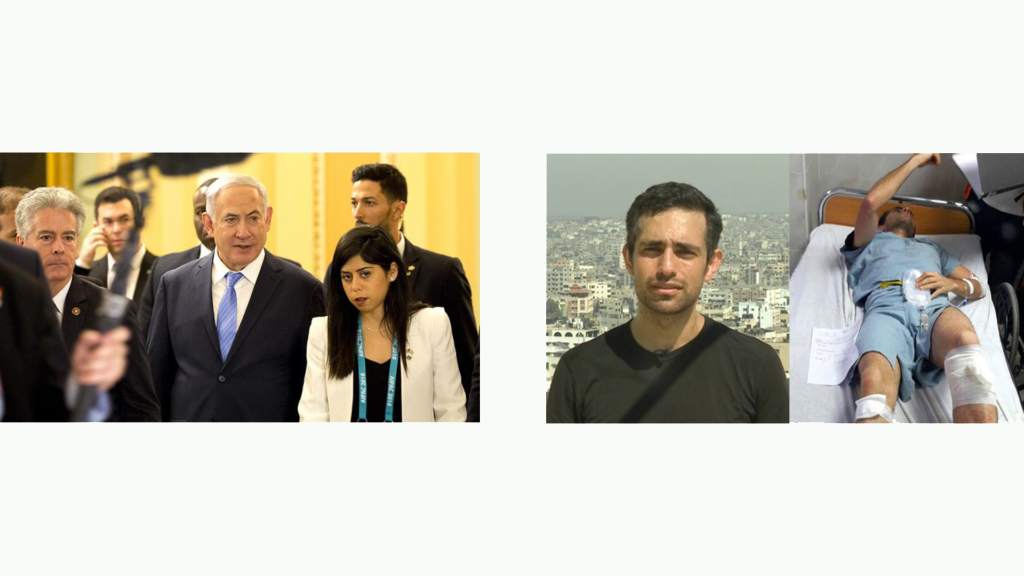

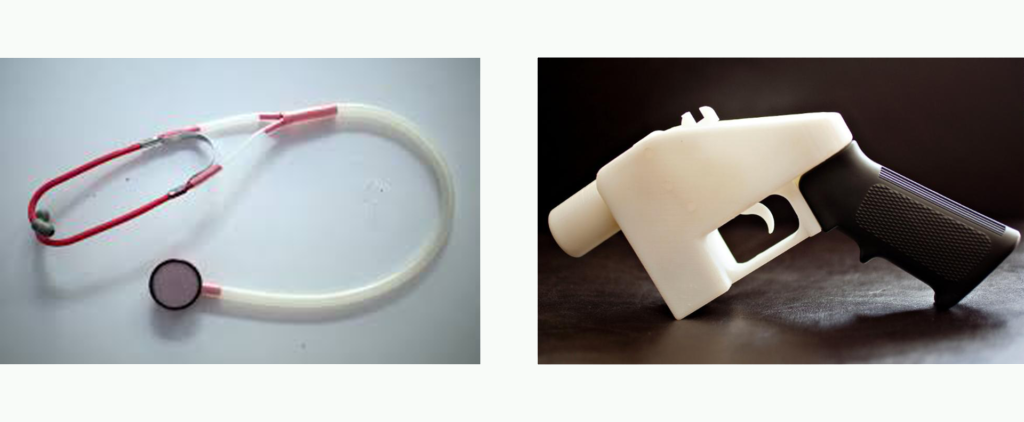

In 2013, Palestinian-Canadian doctor Tarek Loubani released his open- source plans for a 3-D printed stethoscope. This invention means that Gaza (where he works part-time in Al Shifa Hospital) is now self-sufficient in this fundamental technology, despite the best efforts of Israel’s blockade. A simple split screen, juxtaposing the original and the remake, makes the argument succinctly, even as it produces a back-and-forth oscillation, a dialectic that encourages us to contrast and compare.

Four years later, May 14, 2018: news channels around the world featured Loubani in another split screen, one that was as stark in its own way as this stethoscopic dialectic. On the left, Israeli Prime Minister Bibi Netanyahu, triumphantly attending the opening of the US Embassy in Jerusalem. On the right, on the same day, a photo of Tarek, shot in both legs by Israeli snipers while he and a team of medics were dispensing 3-D printed tourniquets to unarmed protesters in Gaza. Despite the extreme asymmetry of these images, an uncanny synchronicity seemed to oscillate, back and forth, nervously.

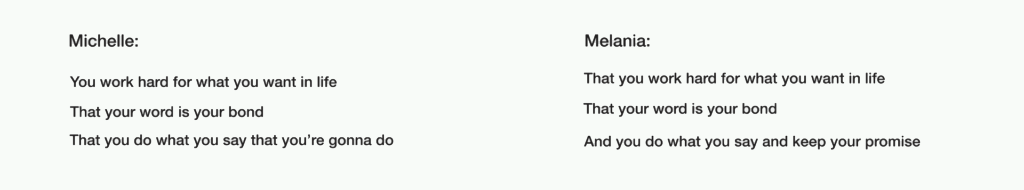

Two years earlier, when Melania at the Republican Convention was busted for stealing Michelle’s words, the nervous oscillation was both more peculiar and more obvious. Toronto artist Daniel Cockburn concluded that a forensic comparison of the two would be piquant.

He stayed up all night editing, and was about to post his stereoscopic results, when alas… he discovered he was late to the party. Three other versions were already trending on Youtube, and by noon there were sixteen variations on this split-screen theme of singing someone else’s song without permission. Even CNN got in on the game. Melania and Michelle, taking the “ok” out of karaoke. M & M, putting the “copy” back in stereoscopy.

In a Youtube universe where split screens tsunami us at every representational levee, where montage drenches us not just between shots, but also within the chopped-up image of the screen itself, this essay considers an oblique yet arguably ascending variant of this species: the shot-for-shot remake, especially when the original is displayed side by side with its copy. I arrived at this topic through hands-on contagion, when I embarked in 2012 on the production of a shot-for-shot (S4S) remake of Jean Genet’s 1950 erotic prison classic Chant d’Amour. In the process of mimicking /echoing /approximating /quoting /shadowing/copying Genet’s iconic frames, but through a filter of contemporary Middle East tensions, three intriguing questions emerged for me: 1) a consideration of the nervous arguments that such juxtapositions seemingly must produce, with our eyes forced to oscillate between the original and remake, contrasting and comparing, never resting; 2) an engagement with the resultant verfremdung of such uncanny unease, an alienation which blocks identification even as it heightens frissons of critical difference; and 3) a speculation about the potential digi-activist uses that such S4S split-screen duets might be recruited for, within a spectrum of social justice cinema. In circuitously and somewhat willfully thinking through such an (ir)resistible rise of these S4Ss, across a spectrum of moving image cultures—high and low, poppy and stroppy—and working backwards from M & M, I’ve found it useful to recruit the slightly sideways metaphors of stereoscopy and karaoke, to better argue with these dynamic duos of master and copy, original and remake.

****

The Dissonance of Hand-Printed Gauze

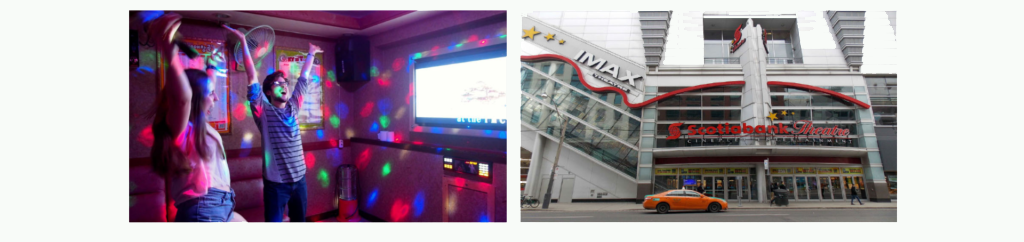

Commencing in mid-nineteenth century Europe as leisure entertainments that targeted an ascendant bourgeoisie, karaoke and stereoscopy produced enticing and profitable commodities for the burgeoning start-up industries of sheet music and picture postcards respectively.

175 years later, we easily recognize their transmedial progeny in the modern day institutions of K-pop norae-bang parlors in Toronto’s Koreatown and the 3-D multiplex screens of Toronto’s Yonge-Dundas Square.

Think of nineteenth-century stereoscopy as producing the shortest movies in the world, consisting of two frames only, one mimicking the other—almost identical, but not quite: Melania not quite Michelle.

(Think of the humble twentieth-century photo booth strip as a poor cousin, producing the next-shortest movie, consisting of four frames…

but it’s doubtful that M ‘n M will ever make a photo booth movie together.)

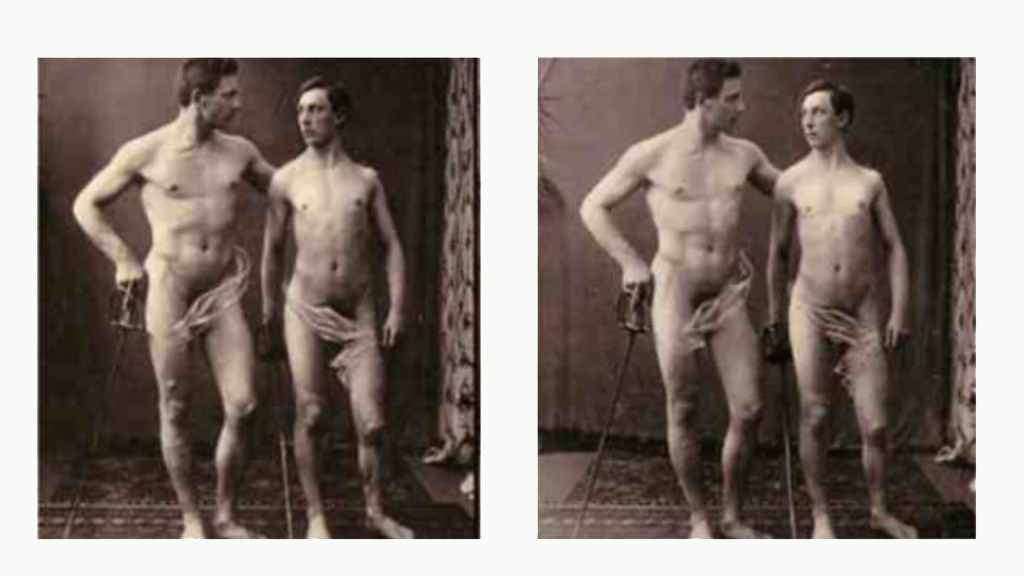

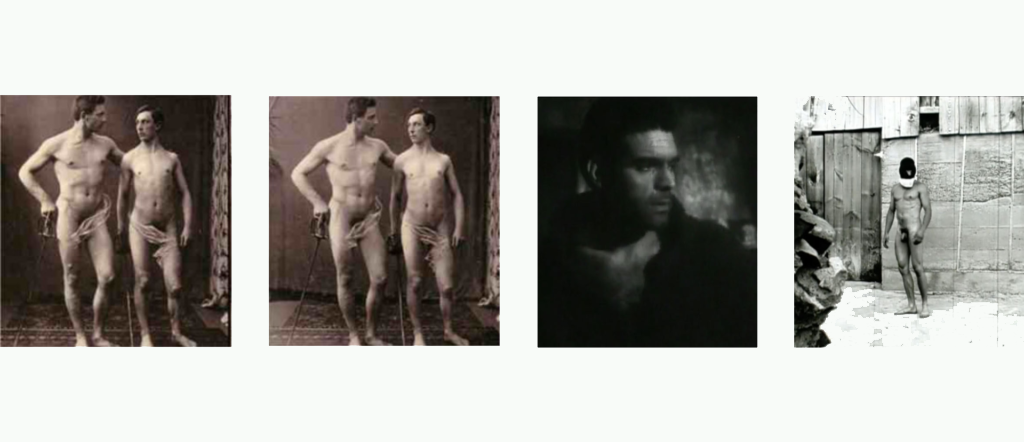

Consider this early erotic, French wrestling stereogram from 1870. Intellectually, we know that the two images must be slightly different, accounting for the discrepancy and distance between the right and left lenses, replicating the difference between our right and left eyes. (How otherwise would they produce their desired illusion of three dimensions?) Yet we search in vain. The men appear absolutely identical in both frames.

We do notice more curtain in the left frame. We do notice slight discrepancies in the gauze that covers their dicks (but then we remember that such gauze was hand-painted onto the prints to evade the long arm of the mail censors).

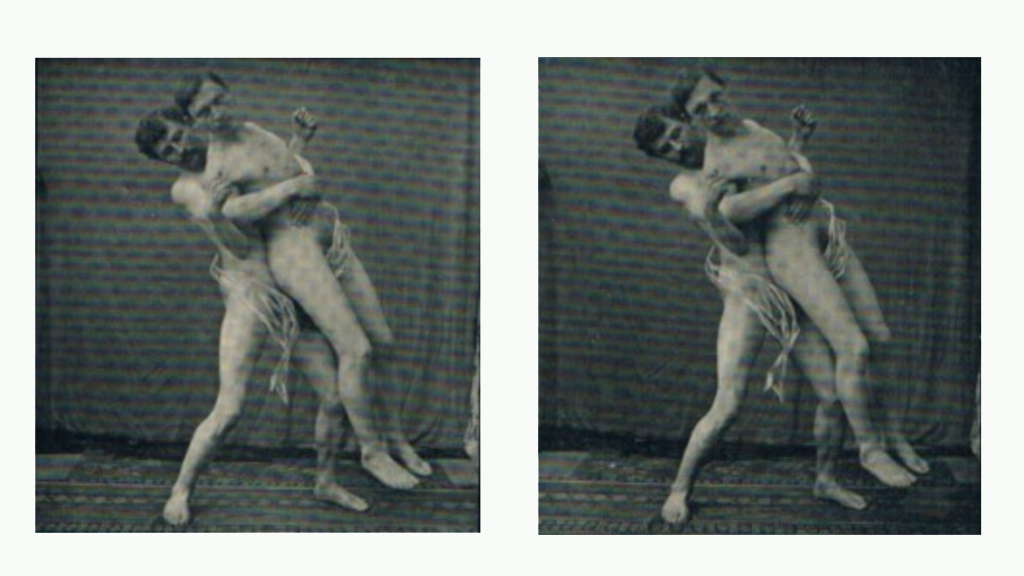

The same men, a new pose. More hand-painted gauze that can be washed off in the privacy of the customer’s bedroom. As an object, such a stereogram both intensifies and diffuses our excitement. We anticipate our intensive 3-D immersion in their freeze-frame wrestling match, once we put the card in our stereoscope viewer and enter their conjoined ring. Yet pre-viewer, our scopophilic gaze splits nervously between the two frames, unable to choose— desire thus diffused, eyes clocking the vibrating dissonance between these two pictures that are identical, and yet are not.

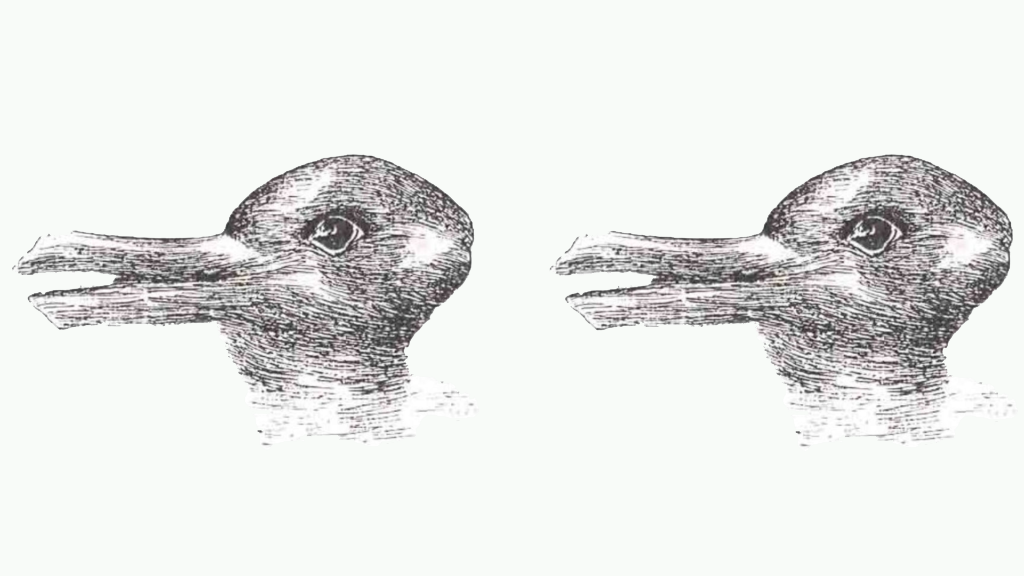

Rabbit? Duck? Both? Engaging the topic of irony, Linda Hutcheon via Bakhtin and Booth argues that “this process of differentiation and relation involves a rapid oscillation between two distinct meanings: denotation and connotation cannot be seen simultaneously but are also inextricable from each other.”

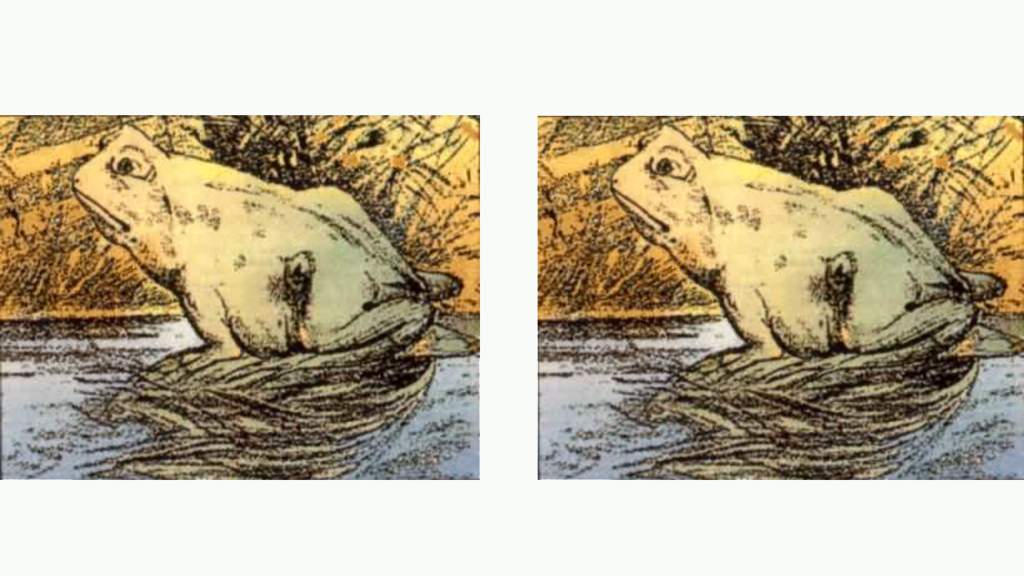

Frog? Horse? Both? Does this dialectic duet of a stereogram render two naked men inevitably ironic? Hutcheon insists that irony is always mediated by the subjectivity of our discursive communities—

and so we understand that these wrestlers in 1870s France have nervous, vibrating, oscillating meanings that are distinct from the meanings of my naked S4S Genet-penguins in 2012, which I shot at filmmaker Phil Hoffman’s farm in Mount Forest, Ontario, a stand in for the Israeli separation wall. (In advance of our shoot, I showed my penguins these wrestling stereograms as a reference.)

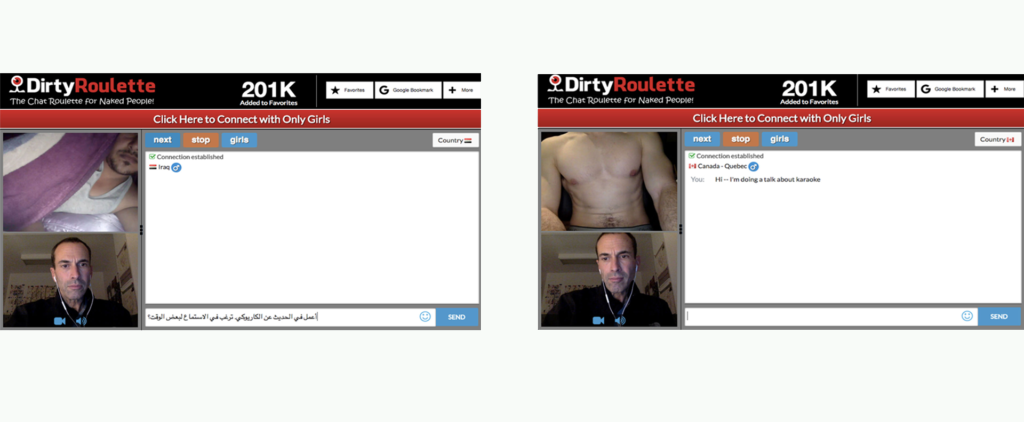

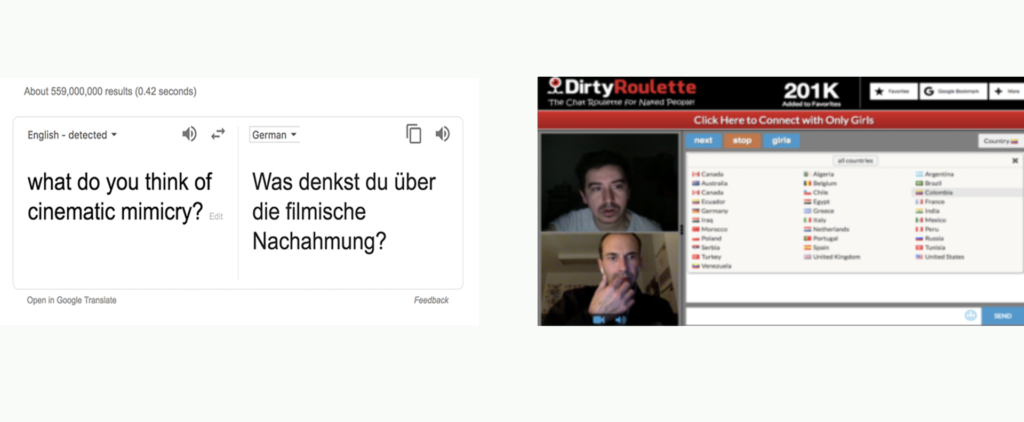

My penguins and I also talked about Chatroulette and its many ubiquitous cover versions (Omegle, Bazoocam, Dirtyroulette), invented by seventeen-year-old Moscow high school student Andrey Ternovskiy.

The dialectic here is a vertical stereoscopy, where the vibrating, oscillating meaning between the two frames, one on top of the other, is navigated on the basis of shaky recognition: of sameness and distance – NEXT – of difference and desire – NEXT – or the lack thereof – NEXT – of the unknown person who may “next” me for unknown reasons, even if my reasons for “nexting” them are equally banal. There are possibilities of engagement, via the chat function; and possibilities of translation, via the grace of Google Translate. At various times, we had “Chatters” from Israel, Egypt, Lebanon, and even one from Gaza briefly… and could translate greetings into Hebrew or Arabic.

These frame-grabs are from a live Dirtyroulette session that was conducted simultaneously with the presentation of this talk, as part of the Poetics of Documentary conference at the University of Sussex in 2017 (with first-time Rouletter and fellow filmmaker Lizzie Thynne nimbly navigating the live interface with wit and vigor). The goal, equal parts whimsical and sincere, was for us as a conference audience to engage with random global punters in these shared S4S questions of oscillation, verfremdung, and activism. Our stereoscopic audience was able to hear and see what we were talking about, and at times chose to contribute to the conversation through the chat function (though more often they chose to “next” us, even as Lizzie occasionally chose to “next” them).

****

Mimicry Confronts a Wall of Spectacular Power

Karaoke: the commodification of the sing-along. In the same epoch that stereoscopic crotches were being gauzed in Europe and North America, the dual rise of the sheet music and upright piano industries created an expanded sing-along pop music economy that would evolve over the next century into the varied karaoke technologies of our post-Vietnam era: VCRs, DVDs, X2000, VCDs, laserdiscs, MP3+G, Blu-ray, and increasingly, Youtube.

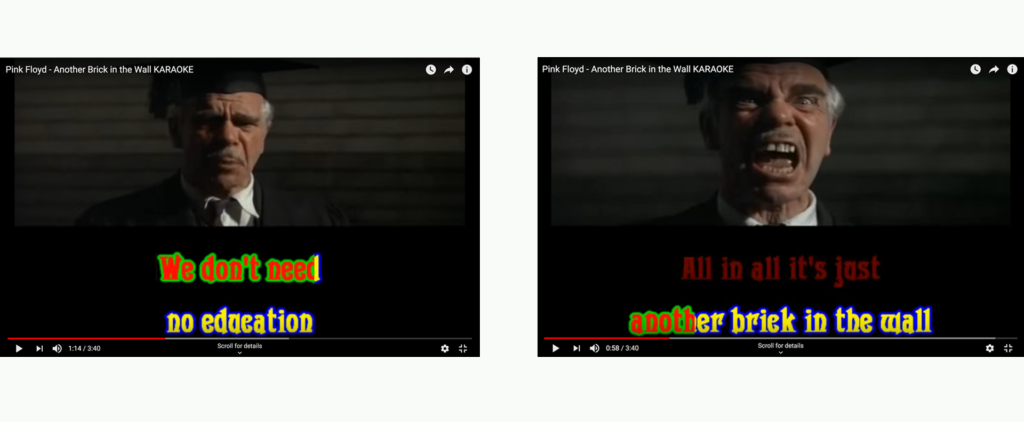

Consider the stereoscopy of karaoke (which means “empty orchestra” in Japanese), where the ghost of the original always lurks in the shadows, haunting, taunting, and augmenting my amateur performance. When I sing Pink Floyd’s Another Brick in the Wall (#170 of the top 500 karaoke songs of all time) in a norae-bang parlor on Bloor St. in Toronto; when I sing “we don’t need no education,” navigating the Lego-colored typography, I can’t hope to make the song my own when Roger Waters’s original vocal is brain-wormed so emphatically into our collective hippocampal storage lockers. The display may not be split screen, but the sing-along video that guides my performance still evokes my eerie stereoscopic counterpoint. My rendition may aspire to sincere tribute or salacious treachery, but ultimately, I’m locked with Roger in a mimetic duet.

Like most of the top 500 karaoke songs, “Another Brick” has multiple ASL (American Sign Language) versions available on Youtube, with hearing-impaired fans posting their performances—sometimes signing on a stage in front of “the Wall” music vid, sometimes signing in front of an actual wall. For these hearing-impaired performers, their duet with Roger isn’t based on his voice so much as his compulsive visual omnipresence, captured during his global half-billion grossing, four-year The Wall tour (2010–13), the third most successful tour of all time (after U2 and the Rolling Stones, bien sûr).

With each of the 219 shows Roger played, he raised the issue of Israel’s Apartheid Wall, and spoke out in favor of the BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) movement, promoting justice for Palestine.

“We don’t need no thought control.” Other people’s words. In his sequel to The Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord wrote, “The spectacle proves its arguments, simply by going round in circles: by coming back to the start, by repetition, by constant reaffirmation in the only space left where anything can be publicly affirmed…. Spectacular power can similarly deny whatever it likes, once or three times over, and change the subject, knowing full well there is no danger of any riposte.” Inevitably, Debord has been dusted off as a prophet of our spectacular Trumped-up moment, reminding us of our complicity in his spectacular supremacy, cautioning us to resist succumbing with wan SNL satire to this engulfing media tsunami. Can karaoke and stereoscopy transcend their status as mere symptoms of our junk culture epidemic? Can split screen offer us more than repetitive, circular parlor games? Can the Roulettes and the Tweets and the ’grams function as more than wan echo chambers? In this homo-national moment, has the formerly radical, queer-camp potential of karaoke, formerly the subversive fiefdom of lip-syncing drag queens, been fatally defanged by mainstream inclusion?

Let’s explore these questions through the prism of cinematic mimicry: What does it mean to perform a cover version of someone else’s film? How does the new version stereoscopically vibrate in relation to the original? How do traditions of satire and agitprop navigate the uncanniness of split screen? How did these questions shape the film that my penguin actors and I made in Mount Forest, a shot-for-shot 16mm hand-processed remake of Genet, intended as a work of Palestine solidarity?

****

S4S: A Queerish Inventory

Cinematic mimicry. This shot-for-shot impulse can be broken down into subcategories of activity, comprising a lexicon of karaoke-like practices. With necessary overlaps, these include the tactics of satiricoke, plagiroke, approximoke, culminating in the full-throttle stratagems of verbatimoke, and documoke. However, today we’ll begin with their visual arts cousin, archimboldoke, that venerable tradition of producing cover versions of others peoples’ pictures, through the adroit use of unexpected objects. Named for the sixteenth-century Italian master Giuseppe Arcimboldo, and inspired by his use of fish and vegetables to create trompe l’oeil portraits, photographic riffs on this practice flourish today, including banana masks and Mona Lisas made of fruit.

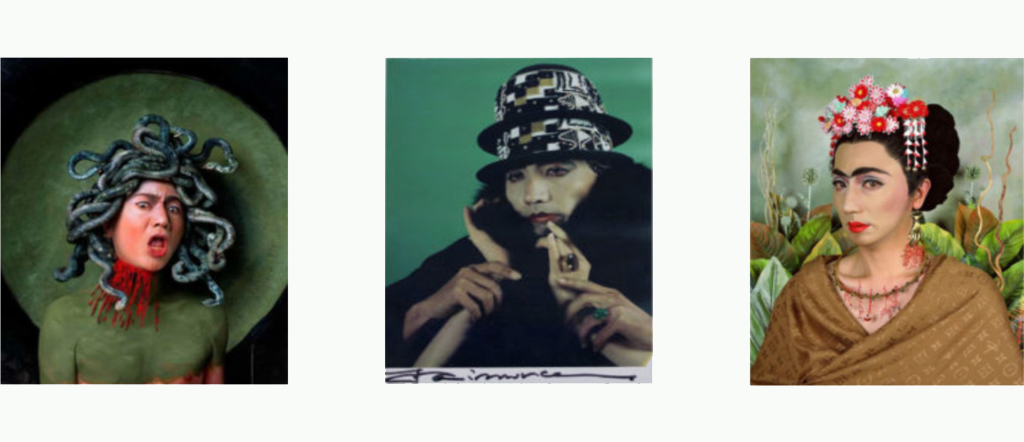

Then there’s Vik Muniz, recreating Caravaggio’s Medusa (1597) out of garbage and spaghetti, whose karaoke remains urgent through his collaboration with Brazilian workers.

There’s Yasumasa Morimura, photographically impersonating Medusa, Frida, Duchamp. His karaoke, even as it forthrightly transgresses codes of race and gender, nevertheless runs the risk—like much culture jamming—of becoming a coy parlor trick. Hutcheon’s nervous, oscillating, dissonance between original and copy can feel stale—dated in these self-portraits from twenty years ago.

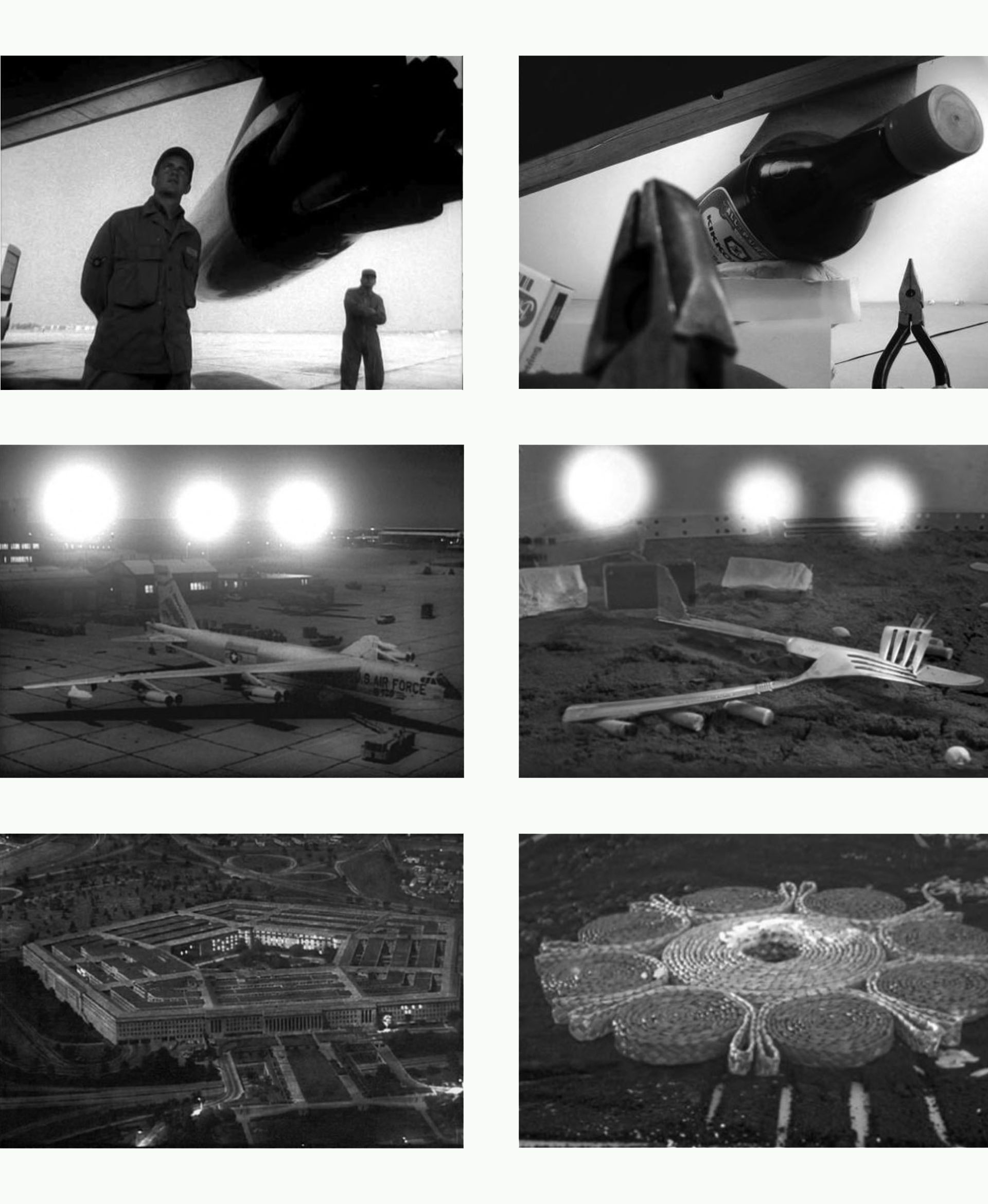

There’s Kristan Horton, creating a shot-for-shot remake in still photographs of Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964), with pliers for a mechanic, forks for an aircraft, and a trivet for the Pentagon. Call it kitchen karaoke.

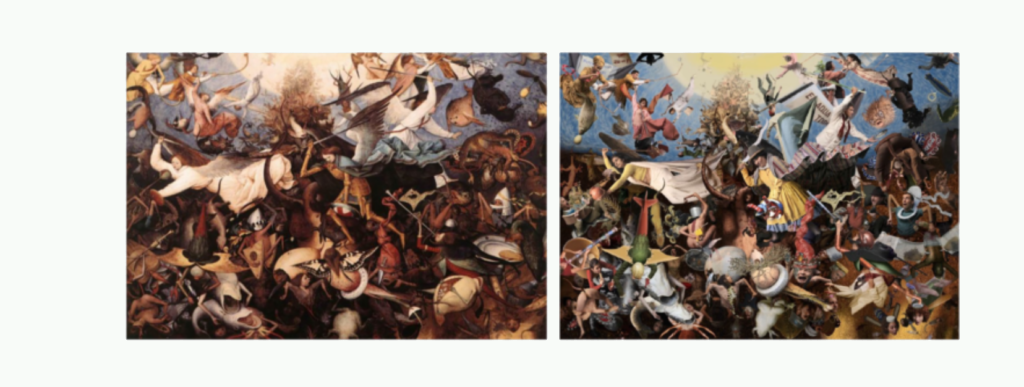

There’s Beveridge and Conde having their photographic way with biblical Bruegel the Elder to construct an urgent parable about globalization and water, a stunning work of ironic counter-spectacular karaoke, featuring a choir of mannequin-challenged freeze-frame performers. (That’s me in the toilet.)

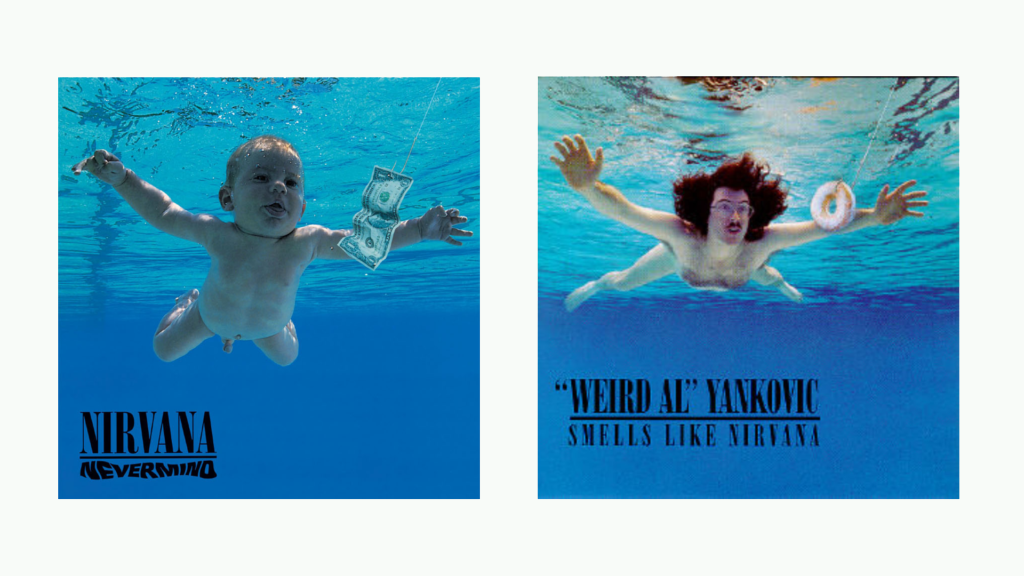

Such tactics of visual mimicry easily adapt to the big screen and extend to both moving images and sound, achieving karaoke’s nadir in the tame, lame games of Weird Al’s music videos, the new-lyrics-for-familiar-melodies trope that launched a thousand birthday tributes and office party send-ups.

Yet his tactics are a foundational staple of meme culture, with new words making familiar melodies uncanny, capitalizing on the viral replication of ironic dissonance. Perhaps no one represents the triumph of this tactic more memorably than Randy Rainbow, a self-described Broadway song- and-dance fag whose musical Cole Porteresque makes assaults on Trump’s first term including jaw-dropping takedowns of current news stories, like Desperate Cheeto (“Despacito”), Rudy and the Beast (Beauty and the Beast) and How Do You Solve a Problem Like Korea? (“How Do You Solve a Problem like Maria?”). His ability to craft deft lyrics within tightly edited green screen culture jams makes him one of Trump’s most formidable culture vultures. In my dreams, I like to think we swim in the same meme pool. In 2016, with longtime collaborator Dave Wall, we rewrote West Side Story’s “Officer Krupke” to transform it into a history lesson in Zionist anti-BDS opportunism and censorship.

This new-lyrics-for-familiar-melodies tactic has found widespread parallel expression within visual culture for decades. Take this Brokeback meme of 2007, where dozens of hetero Hollywood narratives were “brokebacked” for their latent subtexts, riding high on anxieties regarding the gay marriage culture wars.

In the same period, Toronto artists Johanna Householder and b.h. Yael created a series of shot-for-shot remakes of iconic scenes from Hollywood classics that skewer male hubris and angst. Here’s Householder lip-syncing to both Schneider and Brando’s lines in a ghostly stereoscopic restaging of Last Tango‘s butter scene. Here she plays Dave in 2001: A Space Odyssey, where Hal and the space station are karaoked in the manner of Arcimboldo but with household objects and appliances.

The accelerated logic of memes’ mimetic frenzy met its master when Ellen green screened Bernie into Drake’s instantly-copied “Hotline Bling” video.

Of course, all roads to Drake seem to also lead to Beyoncé—and to the obsessive online subculture of former fans using split screens to forensically expose her compulsive plagiroke tendencies (as witnessed by the quarter million results I get when I do a “Beyoncé and Plagiarism” Google search). Here’s familiar S4S forensics of her remakes of video artist Pipilotti Rist, choreographer De Keersmaeker and, of course, Gwen Verdon/Bob Fosse.

Some have tried to mount defenses of the Beast, arguing that all art is of course appropriation built on the backs of what’s come before, that every work of creation by necessity mimics, copies, steals. Some argue that she’s only participating in a voracious culture of cover versions, where the act of singing someone else’s song has become the defining act of our digital citizenship. Surely the deservedly viral covers of Single Ladies by Michelle or Glee’s queerish football team, which likewise steal—however obliviously—from Verdon/Fosse, must complicate any parsing of the complex webs of capital, commodity, and spectacle which buttress her gloriously beastly industrial-scale output.

The riches of approximoke revolve around the vaunted traditions of parody. John Gross identifies parody as flourishing in the territory between pastiche and burlesque, while Mikhail Bakhtin argues that parody is inevitable in the life cycle of any cultural genre. Today we’ll briefly visit three subspecies of the field: fan parodies, emerging from an excess of love (wanted or otherwise); minimalist parodies, which celebrate the virtue of achieving parodic gold by doing less; and deconstructive parodies, which engage with their sources by taking them apart. In all three, the tactic can be tribute or treachery, seeking to exalt or subvert—perhaps both, bien sûr.

Crowdsourced remakes of beloved classics include the justly celebrated 2010 Star Wars Uncut, where 473 global collaborators recreated fifteen-second sequences from the original, using tin foil, cardboard boxes, and gaffer tape, Arcimboldo-style. Key scenes from The Matrix (1999) franchise have been exquisitely rendered in Lego, while Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) was exactingly recreated shot-for-shot by three Mississippi teens over the course of seven summers. A chunk of The Hunger Games has been remade completely underwater. In all cases, the multinationals that own the original properties first balked, then demurred, eventually choosing to leverage these diverse semi-private, semi-communal efforts for their PR value. In all cases, the original soundtrack provides the familiar polished spine, gangplanking these slapdash, creaky, unknown vessels back to the well-known shores of the originals. This reliance on other people’s soundtracks acquires an additional eeriness when Aqua-Katniss “speaks” her lip-synced lines, literally amplified in these oxygenless liquid depths where words aren’t usually possible.

In the case of the crowd-sourced database of Dziga Vertov’s 1929 Man with a Movie Camera called The Global Remake (ten years in the making and counting), volunteers are invited to choose a shot or sequence and remake it for our digital age, underlining, counterpointing, or countermanding the meanings of the original. In this case, a new soundtrack is being collectively composed in place of the silent original. Vertov hubristically declared his celebratory urban documentary “an experiment in the cinematic communication of visible events without the aid of intertitles, without the aid of a scenario, without the aid of theatre”—a work of unknown horizons. In contrast, The Global Remake is notable for its modest irony, its lack of triumphalism, its humble engagements with our world today.

Minimal parody adopts the structural mantra to do more with less. The so-called Bad Lip Reading series in fact delivers the opposite to viewers, courtesy of skilled actors and deft sound editing. The wit may be skittish, but the uncanny lip-sync of these new nonsense words fascinates. English comedian Peter Serafinowicz adopts an even more rigorous aesthetic, preserving both words and picture in their entirety, but deploying his critique of Trump through the devastating use of his verbatim vocal avatars: “Posh Trump,” “Cockney Trump,” and “Sassy (or is it Sissy?) Trump.”

For over a dozen years, the Downfall series has remained the go-to meme for parodying current affairs, in part because of the ease of execution. Spawning thousands of versions, the Downfall parodies have their own online community called untergangers, with fan-founder Stacy Lee Blackmon hosting 1,500 versions on his Youtube channel. Shot-for-shot and word-for-word, the only element that changes are the false subtitles. As a vehicle for timely no-budget rejoinders, it’s hard to beat. Like the M & M split screen, this “Mufti” version of the iconic Downfall (2004) scene went viral hours after Bibi Netanyahu declared that Hitler got the idea for the Final Solution from Palestine’s Grand Mufti in 1941.

Techniques of parodic karaoke can critically deconstruct their source text even as they mimic, appropriate, or lampoon. Peter Greenaway’s 2007 feature Nightwatching, in sync with the photographic restagings with actors of canonical paintings by Conde/Beveridge or Morimura, performs visual karaoke on the Rembrandt masterpiece The Night Watch (1642). Reminiscent of the living tableau tradition, and staged as a behind-the-scenes art historical narrative, this structuring device allows Greenaway to create a film chock full of Dutch history, class struggles, murder conspiracies, and hot sex—seemingly within a single group shot.

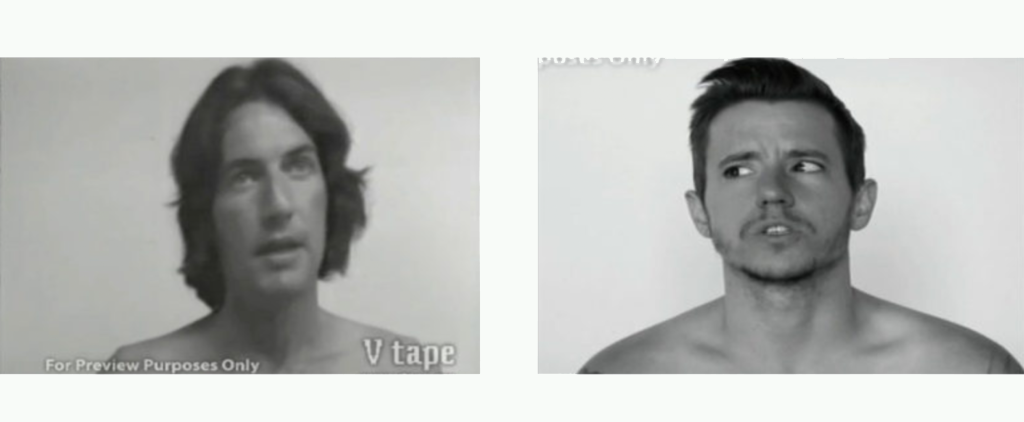

Shot-for-shot remakes of early video art classics are an inevitable navigation of legacy, inspiration, and dialogue between generations. For instance, both Martha Rosler’s mock cooking show, Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), and Lisa Steele’s scar index, Birthday Suit (1974) have spawned dozens of remakes by new generations of artists. Colin Campbell’s 1972 Sackville, I’m Yours inspired a remake titled I’m Yours (2012) by transgender activists and artists Chase Joynt and Nina Arsenault, paying homage to the fragmented interview format of the original but taking the content in new transgressive directions.

Verbatimoke. Shot-for-shot remakes within the entertainment industry are rare birds indeed (the most common being parodies featured on The Simpsons and Family Guy). Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964) is widely assumed to be a slavish shot-for-shot version of Yojimbo (1961), but though it certainly borrows from Akira Kurosawa in select compositions and sequences, it’s nowhere near being a true shot-for-shot. For this reason, Gus Van Sant’s 1998 remake of Hitchcock’s 1960 Psycho stands alone both because of its conceptual and structural rigor (word-for-word, shot-for-shot, score-for-score) and because it was such a resounding commercial and critical flop. Roger Ebert called it a xerox copy, saying it “demonstrates that a shot-by-shot remake is pointless; genius apparently resides between or beneath the shots, or in chemistry that cannot be timed or counted.”

On the left, a layering of the two shower scenes by a fan; on the right, “retired” filmmaker Steven Soderbergh’s montage of same, taken from Psychos, his 2014 full-length mashup of the two movies. Seen together, we can compare the lures and limits of these two contrapuntal options: split screen vs. superimposition, wipes vs. dissolves.

Trent Harris’s The Beaver Trilogy (2000) is a hybrid that remakes itself three times, with vague attempts at Psycho-like shot-for-shot rigor. The first segment is a doc portrait of Groovin’ Gary, a Beaver, Utah, teen who stars in his own small-town talent show as Olivia Newton Dawn. The second is a dramatic version, two years later, featuring an unknown Sean Penn, attempting a shot-for-shot remake of Gary’s story on a budget of $100. The third is Harris’s thesis film at the American Film Institute, this time starring Crispin Glover as Gary and infecting the story with invented inflections. It was remade again in 2014 as a what-ever-happened-to documentary, bringing this baroque remake project full circle back to its doc origins.

For my money, though, the ultimate example of doppelganger exactitude was achieved by the US armed forces stationed at Kandahar Airport when they lip dubbed Carly Rae Jepsen’s ultra-memeable 2012 hit “Call Me Maybe.” The soldiers replicated not just every shot but every fey gesture and saucy hair flip of the Miami Dolphin cheerleaders, whose own bikinied version joined a veritable stampede of lip-sync, lip dub, flash mob, and celeb-cover versions of Carly’s pop-a-cork juggernaut. (Interestingly, the Army brass gave this gender-bending bit of boys-will-be-boys popwashing two thumbs up, perhaps the better to distract from recent memories of Abu Ghraib, et al.)

Documentary shot-for-shots are even rarer than their fiction counterparts and navigate even more fraught journeys through issues of ethics, authorship, and voice. Shulie (1997) by Elisabeth Subrin is a remake of a lost doc portrait, also called Shulie, made thirty years earlier and then shelved, about a young art student named Shulamith Firestone, who three years later went on to pen the extraordinary feminist manifesto The Dialectic of Sex (1970). Subrin’s decision to remake the original verbatim, with as much precise rigor as the Kandahar army boys, was hailed by the New York Film Festival as “a cinematic doppelganger without precedent” and by Ruby Rich as “not a clone in the end, but a brilliant rethinking of history,” one which forces viewers to navigate the gender and racial inequities of that era with eerie engagement.

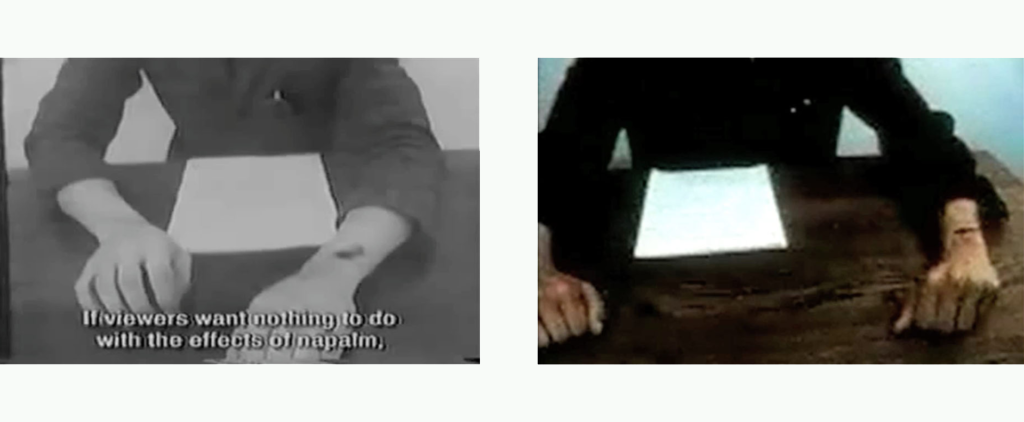

Jill Godmilow’s What Farocki Taught (1998), a “perfect stubborn replica” of Harun Farocki’s 1969 documentary about napalm, Inextinguishable Fire, attempts a similar shot-for-shot reconstruction, with the goal of making this classic German essay film available to English-speaking audiences. Farocki himself objected, however, arguing that Godmilow and others should have mobilized to secure distribution for the original, not expend their energy on copying a fellow living filmmaker. In subsequent comradely conversations with her, he argued that he would have been more comfortable if she’d made her version more distinctly her own. The ethical claim was certainly not about questioning her right to copy—Farocki’s own work is distinctive for its extensive use of other people’s images and words—but rather that she didn’t remake the copy distinctly enough. Godmilow’s version, in the wake of subsequent decades and Farocki’s death, has morphed again to gain it’s own archival aura, both now deservedly recognized as landmarks in evolving documentary debates.

The Battle of Orgreave was a violent confrontation between police and miners during the miner’s strike in 1984; a reenactment of the Battle was staged by artist Jeremy Deller in 2001 based on original TV news footage and featuring 800 reenactors and 200 survivors of the original conflict; then, a film was shot by Mike Figgis documenting Deller’s reenactment process. While there’s no pretense to a shot-for-shot recreation of the news footage, and indeed, the differences are striking (note the relative positions of the cameras in relation to the cops), it’s nevertheless easy, indeed inevitable, to lose track of what is real and what is restaged.

Other people’s words. Agitpropoke. Many artists, including Roger Waters and Banksy (but not, sadly, Weird Al or Beyoncé), have spoken out against Israel’s apartheid wall. I went to the Mount Forest Film Farm Retreat in 2011, determined to use local walls to shoot a short experimental film about the wall that carves up the West Bank into a rat maze, dividing families from their own olive orchards. However, the architecture of this bucolic northwestern corner of southwestern Ontario offers exactly nothing that might suggest those towering brutalist slabs.

I found friendly concrete silos surrounded by fields of mustard. I found crumbling stone remains of outbuildings, overrun with weeds and goats. I found a fence with an open gate in a flooded skate park.

I was searching for walls, but I already had someone else’s pictures, someone else’s song, someone else’s words: respectively, Jean Genet’s pictures, Arnold Schoenberg’s song, the words of Exodus. The plan was a condensed shot-for-shot karaoke remake of Jean Genet’s Chant —a silent black-and-white love story of two prisoners separated by a wall. When he first screened this remarkable twenty-six-minute visual poem (the only film he ever made), it was immediately banned by censors. Today, despite disavowals by Genet himself, the film is acclaimed as an essential cornerstone of global queer cinema, influencing generations of experimental queer auteurs as diverse as Jarman, Gonick, Warhol, Riggs, Julien, Haynes, LaBruce, Trecartin, and Weerasethakul.

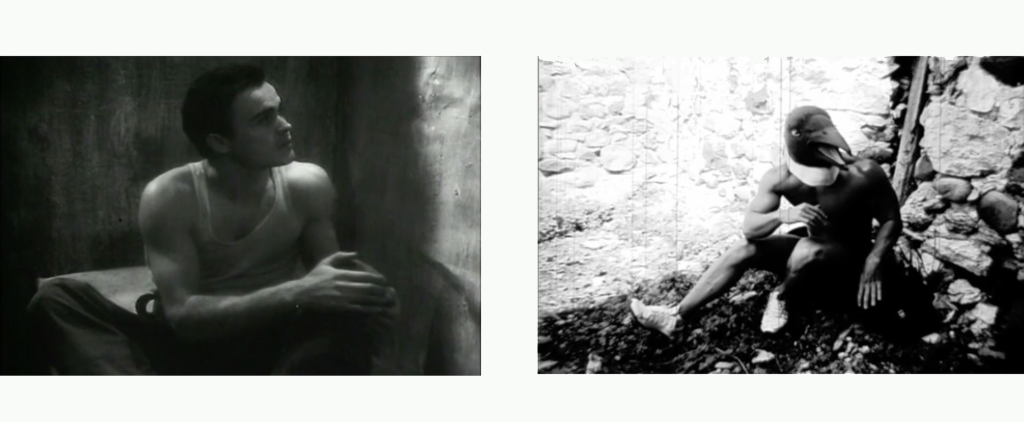

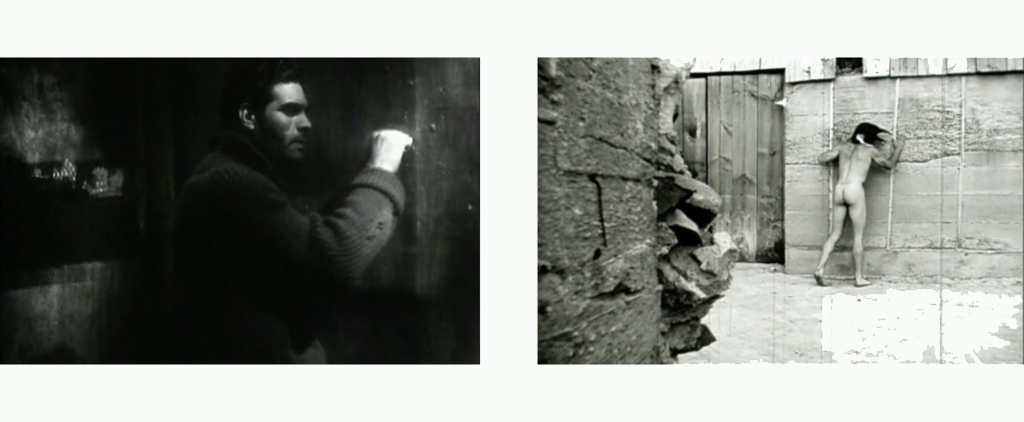

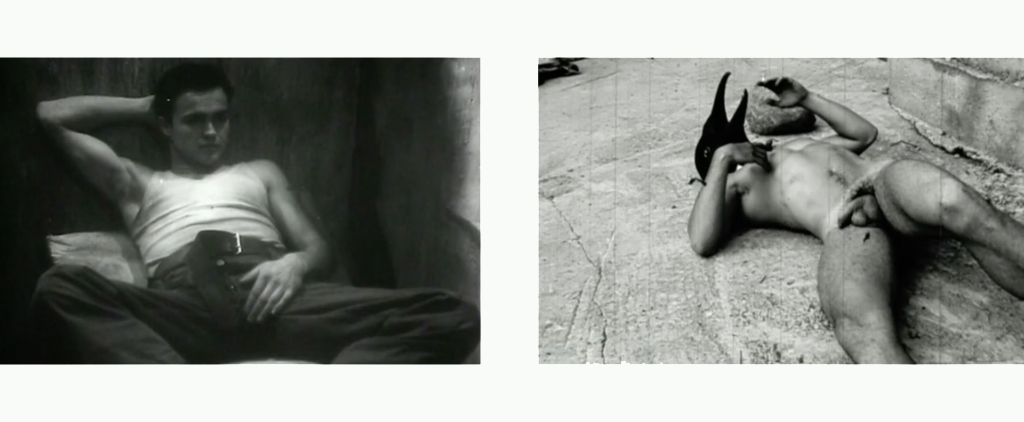

The two cells of the two prisoners become the two frames of their stereoscopic relationship, though they’re sutured together by conventional montage instead of split-screen collage. In my retelling, the urgent French/Algerian context of 1950 is remapped onto the Israel/Palestine conflict of today, this time with an apartheid wall separating the two lovers. Genet’s most famous scene, the blowing of cigarette smoke between the cell walls using a straw from the mattress, became an eerie evocation of the teargas that so often clouds confrontations at military checkpoints.

My chosen structure is split screen: Genet on the left, my recreated Mount Forest shots on the right. My two lovers are naked penguins, inspired by Buddy and Pedro, the actual gay penguin couple who used to bunk together in the Toronto Zoo, and who were exploited by the zoo for cute anthropo-homonational marketing purposes.

The allegorical plot of Un Chant D’Amour, set in a French prison, concerns a lust triangle between a guard, a convict, and an older Algerian prisoner, culminating in the latter’s dream fantasy where he and his beloved romantically romp beyond the prison walls, exchanging flowers and caresses. With unmistakable anti-colonial overtones, each character symbolizes archetypes in the manner of Genet’s schematic plays, epitomizing roles of corrupt, deviant state authority (the Guard), youthful anarchic rebellion (the Convict), and subaltern agency/ambivalence (the Algerian).

Hanging my 16mm hand-processed Bolex-shot remake up on the clothesline beside Genet’s original traffics invites a similar oscillating, dissonant reception (like the previously mentioned wrestlers or M & M), eliciting an argument about what is the same and what is different. Eyes ping-pong by necessity between his erotic naturalism and my avian campfest. It’s a provocation that joins decades of queer solidarity activism with Palestine—from Genet’s own 1986 memoir Prisoner of Love to Elle Flanders’s 2005 doc Zero Degrees of Separation, from GLQ’s 2012 special issue on Pinkwashing (edited by Patty White) to The Homonationalism and Pinkwashing Conference at the New School in 2012.

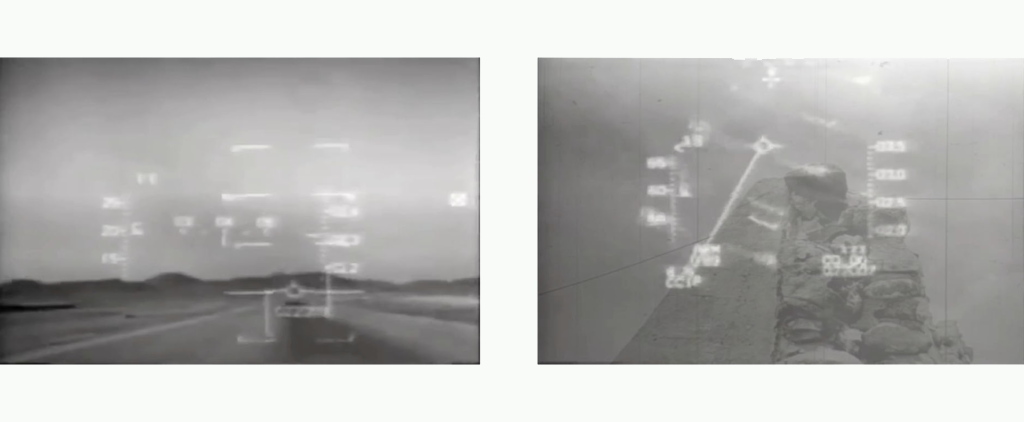

Several elements make this shot-for-shot remake distinct: the penguins, bien sûr; the ironic appropriation of Schoenberg’s Zionist opera Moses und Aron (1932); and the discovery of cockpit footage from the 1981 Israeli preemptive strike that was dubbed Operation Opera. This dark bombing operation became the grainy bookends of this handmade and purposely inadequate aproximakoke of Bibi’s accelerating occupation, which killed sixty civilians on the same day that Tarek Loubani was shot in both legs.

****

The Uncanny Valley: Arguing with the Inventory

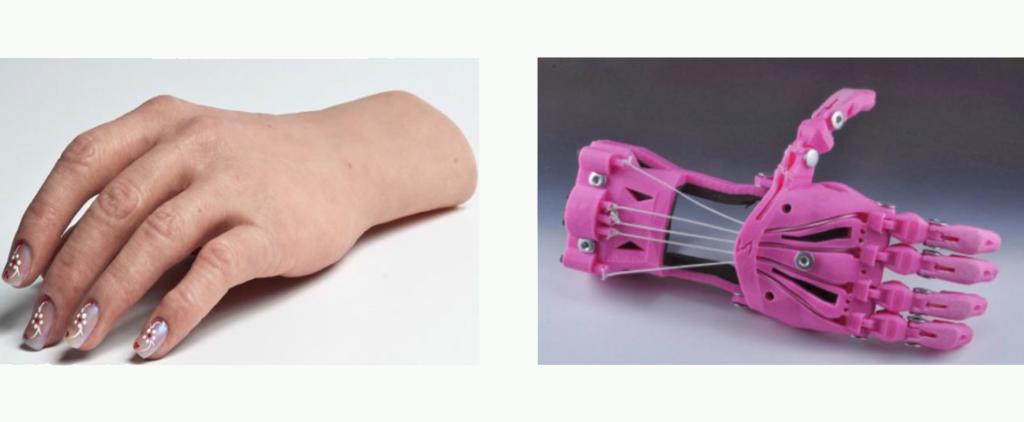

Robotics scholar Masahiro Mori coined the term “uncanny valley” to describe those feelings of eeriness experienced when encountering human replicas which appear almost, but not exactly like real humans. Mori described how both robotic limbs and healthy limbs can inspire positive affective responses, but the prosthetic hand, with its uncanny associations of the corpse, invokes revulsion. In 2013, I planned to travel to Gaza to make a film about Tarek’s work creating both 3-D-printed stethoscopes, and also printed hands, attempting to address the needs of Palestinian children who lost limbs in cyclical Israeli bombing attacks. In his research, he discovered that while kids responded very positively to the Lego-colored, transformer-styled (and quite useful) robotic hands that he was able to print on his 3-D printer, parents inevitably preferred the realistic (and quite useless) prosthetic hands that so inadequately mimic life.

Freud in Das Unheimliche (1919) describes uncanny effects in terms of “repetition of the same thing,” which leads via Deleuze (Repetition and Difference, 1968) to Hutcheon’s crucial insight that parody is “repetition with critical (ironic) distance, which marks difference rather than similarity.”

Advances in both 3-D printing and 3-D stereoscopic animation have underlined this distinction, producing objects and screen images that are too real, plunging us into the uncanny valley of eerie discomfort (like these creepy, fascinating, unheimlich Printing House doppelganger portrait sculptures that myself and my partner Stephen Andrews are holding). In contrast, parody allows us pleasurable and critical identifications through the deployment of repetition with difference. I’m trying to illustrate this point with these sculptures, but I’m defeated at every turn. Somehow my phone camera makes these 3-D sculptures appear as though they’re flat 2-D photos, and this proof merely resembles a crude photoshop prank.

Let’s instead review these main points in relation to our three concerns:

Following Farocki’s argument, shot-for-shot karaoke remakes gain agency through their deployment of difference, purposely exploring and exploiting the tensions between the original and the copy (Man with a Movie Camera). Attempts at slavish repetition without difference (Psycho) are interesting only when they’re actually juxtaposed with the original (Soderbergh), revealing, inevitably, the micro differences.

The successes or failures of karaoke practices don’t reside with their scale: maximalist efforts (Underwater Hunger Games) and minimalist efforts (Sassy Trump) can equally fascinate, based on the precise critical intervention that their chosen difference offers to audiences, interventions which go beyond stunt status to have actual stakes in our cultural moment.

Righteous attacks on the plagiroke tendencies of Melania and the Beast only reify tired myths of artistic originality, and ignore the fact that Michelle, Rist, De Keersmaeker, and Fosse were all in turn stealing from (and crucially adapting) other versions by other artists, in a rich chain of collective creation. Again, Farocki’s point is the key one: the question is not that they’re performing karaoke, but rather, what have they done to make the cover version their own?

Our digital moment, with a cam in every phone and a soapbox in every Twitter account, implies both a democratization of access to the means of production and an upsurge in new voices discovering the lures and limits of agitpropoke. If karaoke in all its mimetic modes (musical, digital, performative) remains a go-to tactic for activists wanting to reach broad audiences with the siren call of a familiar meme or melody (hello Randy Rainbow), then it’s crucial to remember that the critical capacity of these pop-sampled party tricks is equally available and exploitable by a kill-me-maybe mob of cheerleaders and soldiers, who can dress their monstrous meanings in mesmerizing spectacles of campy fun. For every stethoscope that is 3-D printed, there’s also a handgun.

Split screen is by definition a dialectic, one that undermines affective identification even as it insists on a nervous, oscillating practice of argument and comparison, our eyes performing a type of within-the-frame montage to produce a third meaning through the juxtaposition of two frames (sometimes separated by a wall).

CAPTIF’S D’AMOUR (John Greyson, 2010).

Title video: Captif’s D’Amour, John Greyson (2010).

{1} A version of this was originally presented at the Poetics of Documentary conference, University of Sussex, 2017).